Original Articles: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

An Assessment of Young Adult Perceptions Towards Entrepreneurship in Bangladesh Using a Mixed Methods Approach

Andrew Zimbroff, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Jennifer Johnson Jorgensen, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Abstract

Increased small business creation represents a promising opportunity for new economic growth within Bangladesh, a developing economy currently dominated by agriculture and export manufacturing. While past research has looked into traits important for entrepreneurship, there are many gaps in the literature for Bangladesh specifically. Further, the limited research that is available has focused primarily on quantitative metrics, and largely overlooked perceptions towards entrepreneurship, despite the impact these attitudes can have on entrepreneurial activity. In this study, we aimed to better understand subjective perceptions of entrepreneurship for young adults (aged 18-40) in Bangladesh. We used focus groups and surveys with current and aspiring entrepreneurs to better understand self-identified needs for increased business creation. Results from these efforts were then used to construct statements used for a Q sort, which was completed by 27 current and aspiring entrepreneurs. Analysis of these Q sorts identified four distinct profiles (factors) representing different viewpoints young adults have towards entrepreneurship in their local communities. Results from the Q analysis provide further insights on young adult entrepreneurs’ views and how to better assist these entrepreneurs for future economic growth.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurship Perceptions, Young Adults, Bangladesh, Mixed Methods, Q Methodology.

Introduction

This study aimed to better understand young adult (defined as ages 18-40 in this study) subjective attitudes towards entrepreneurship in Bangladesh. An individual’s attitudes towards business opportunities can have a strong influence on entrepreneurship- belief in one’s own abilities to start a business and perceived desirability of entrepreneurship are two examples that have been shown to be correlated with future entrepreneurial activity (Guerrero et al., 2008; McGee et al., 2009). However, there is currently very little known about entrepreneurial perceptions in Bangladesh. Much of the existing literature focuses exclusively on quantitative metrics like job growth and wealth creation. The limited research available for perceptions within the country is non-comprehensive, conflicting, or out of date (Chowdhury, 2007; Karim & Hart, 2011; Mair & Marti, 2007). Further, past research also does not explore in depth the cause of these perceptions. This illustrates the need for additional investigation into better understanding current perceptions of entrepreneurship within Bangladesh. We elected to focus exclusively on young adults and their views towards business creation.

While others have conducted research on general entrepreneurial trends in Bangladesh, literature is virtually non-existent when focusing solely on young adults, and it is unclear how this population differs from the rest of the country. However, the need for increased entrepreneurship is particularly prominent for this population segment, which has a significantly higher unemployment rate (9.2%) than the rest of the working population (4.3%) (Guha & Mamun, 2016; World Bank, 2013). Further, 36.7% of the population in Bangladesh is between the ages of 15-34. As birth rates continue to decline (fertility is projected to drop below 2.1 births/woman lifetime by 2020), this population will remain a significant portion of the national workforce. Additional research for this population segment is needed to promote future entrepreneurship and economic development (United Nations, 2015).

There is a general consensus amongst researchers that a diverse set of viewpoints (e.g. belief in one’s own ability, perception of entrepreneurial opportunity, etc.) is needed to support robust entrepreneurship and venture growth. Further, there is no “most important” mindset for entrepreneurs, but rather, a collection of viewpoints that all have a significant effect on entrepreneurial activity. Subsequently, we felt it was advantageous to employ a mixed methods approach involving Q methodology for this study. Q methodology identifies factors, or patterns of statements, which correspond to profiles prevalent within an entrepreneurship ecosystem (An ecosystem entails all elements that have an effect on local entrepreneurship, including institutions that support entrepreneurs, business resources and infrastructure, and stakeholders, or individuals that interact with new businesses). This can give a multivariable view of entrepreneurship attitudes than methods used in past literature, which tend to measure and look for correlations among single variables at a time.

The importance of entrepreneurship for promoting economic growth has been widely recognized in countries around the world. As a result, there is extensive past literature identifying traits and mindsets important for encouraging robust entrepreneurship. This literature was referenced during this study and applied to gain current insight into Bangladeshi entrepreneurship. Culture and attitudes towards entrepreneurship can have a strong influence on entrepreneurial activity within a country (Isenberg, 2010). Entrepreneurial activity is more common in countries that embrace entrepreneurs, and don’t stigmatize business risk or failure. Further, communities that celebrate successful entrepreneurs have higher rates of entrepreneurial activity (Lee & Peterson, 2000). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor conducts annual surveys about entrepreneurship in multiple countries around the world. This organization has multiple questions about how entrepreneurs are perceived in their communities. It also asks if fear of failure is a deterrent to entrepreneurial actions (Karim & Hart, 2011).

In addition to overall entrepreneurship attitudes, the perceptions of entrepreneurs towards their own abilities is also a significant factor for robust entrepreneurship activity. Self-efficacy, or belief in one’s own ability, has been shown to be correlated with entrepreneurial success. The term entrepreneurial self-efficacy has been coined and is frequently used as a predictive measure for entrepreneurship (McGee et al., 2009). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor also investigates perceptions of entrepreneurs in their annual surveys. Questions in their survey instrument ask individuals whether they believe entrepreneurship opportunities exist in their country, and if they believe they have the capabilities to start a business (Karim & Hart, 2011). These findings reinforce the need to understand entrepreneurs’ perceptions towards business creation.

Access to capital is frequently cited as an important factor for encouraging entrepreneurship. It can take time for a business to become profitable, and capital from outside sources can help new businesses reach that stage. Further, some businesses need capital for large assets or inventory, and cannot make these large purchases without outside assistance (Feld, 2012). As a result, a developed, accessible banking system can be a strong promoter of entrepreneurship in a country.

Finally, government can play an important, though indirect role in promoting new business creation. The government is responsible for elements that contribute to a pro-business climate, including security, stability, and infrastructure that businesses utilize. Further, it can create policies and laws that promote business development within a region or country (Feld, 2012; Gnyawali & Fogel, 1994). Finally, government frequently plays a large role in providing education and job skills training for its citizens. This education contributes to human capital development for both entrepreneurs and the workers their business hires (Gnyawali & Fogel, 1994). As a result, government plays an important role for entrepreneurship, even when not directly responsible for creating new businesses.

Previous Investigation into Bangladeshi Entrepreneurship Attributes and Attitudes

Bangladesh has struggled to encourage substantial entrepreneurship and new business creation, and past research has identified these challenges. It is ranked one of the lowest countries in the world by the Global Entrepreneurship Development Index (Ács et al., 2018). Research has also identified perceptions that contribute to limiting entrepreneurship activity. The percentage of adults in Bangladesh that feel capable of starting a business is less than half that of comparable world economies. Further, almost two-thirds of adults say fear of business failure deters entrepreneurial actions, nearly double the rate observed in the same comparable economies (Karim & Hart, 2011). However, not all findings paint a pessimistic view of Bangladeshi entrepreneurship. Perceptions of entrepreneurship opportunities among adults was the third highest in the world, and early-stage business survival rates were more than double that of comparable economies (Karim & Hart, 2011). Subsequently, additional research is needed to identify the current status of entrepreneurial perceptions, to better design interventions that can help encourage additional entrepreneurship activity.

Hossain (2006) mentions scarcity of capital as a significant barrier to business creation. Government policies in the 1980’s aimed at decreasing private banking led to stagnation and sometimes contraction of domestic credit and money supply (Heitzman & Worden, 1989). While some micro lending institutions have increased lending in the country (the most notable of which is the Grameen Bank), these loans don’t adequately serve all population and business segments (Mair & Marti, 2006). Modern banking institutions do exist within Bangladesh. However, much of the population has little to no experience with credit and loan repayment, and a lack of credit monitoring in the country means these loans are seen as risky and come with high interest rates (Sharma & Zeller, 1997). All of these factors have led to an under-developed domestic banking system with limited financial services for individuals and small businesses.

Deficient education and training of job skills in Bangladesh have also limited the capabilities of current and aspiring entrepreneurs and their employees. While there are efforts to expand educational access, there are still high rates of student non-attendance and discontinuing formal education (Hossain, 2006). Schools remain underfunded and inefficient, and student learning is limited by low classroom hours, teacher absenteeism, and lack of measurement and accountability. As a result of current deficiencies, NGOs have created non-formal and vocational training centers throughout the country (Shohel, 2015). These centers do not address all educational shortcomings, and young adults in Bangladesh are often lacking the skills needed to create a business.

There have been some attempts to incorporate entrepreneurship education into other business training (Azim & Akbar, 2010; Huq et al., 2017). However, these efforts have mainly been concentrated on university students, and are not accessible by a large percentage of current and aspiring entrepreneurs. As a result, entrepreneurship training is generally insufficient, and many are not prepared for business creation.

Government actions have significantly contributed to the current state of entrepreneurship in Bangladesh. The government has not had a clear set of policies for encouraging small businesses and, at times, has also emphasized large enterprise over entrepreneurship, diverting resources to this area (Khondkar, 1992). Further, the government has not adequately invested in education and training facilities, contributing to the major entrepreneurial challenges. Even when the government has focused on new business creation, high corruption and ineffectiveness have dampened the impact of these efforts (Asadullah et al., 2014). As a result, NGOs have stepped in to fill shortcomings when needed, providing healthcare, job training, and financing. These organizations have received an increasing amount of international aid, increasing their prominence within the country (Murata & Nishimura, 2016).

Further, cultural attitudes towards entrepreneurship have had a significant effect in Bangladesh. Past researchers have observed social and religious stigmas for women who create or own their own business, a problem especially prominent in rural areas. In addition to discouraging women from entrepreneurial ventures, these cultural norms discourage men from working with female-owned businesses (Nawaz, 2009; Rahman et al., 2000). This has caused a noticeable effect on female-owned new business creation, and Total Entrepreneurship Activity (TEA) for males in Bangladesh is more than four times that of females (Karim & Hart, 2011).

Previous Development and Use of Q Methodology

Q methodology stood out as an effective means to measure young adults’ perceptions of entrepreneurship in Bangladesh. For this method, all participants were given a set of predetermined statements and were asked to sort each statement based on agreement or disagreement by placing it on a pre-arranged grid. As stated by Watts and Stenner (2012), all items to be allocated a place in the grid relative to one another, starting with the items they feel most positive about, which will be awarded the higher rankings at the right-hand end of the distribution, running right across, in a continuum, to the items they feel most negative about, which will be awarded the lower rankings at the left-handed end of the distribution” (Watts & Stenner, 2012). The order within each column is not of importance. The Q sort initiates the participant to self- categorizes, and the participant creates meaning through completing the Q sort. Multiple participant Q sorts were collected for this study, and all contribute to the analysis. All viewpoints were combined to understand patterns among all participant viewpoints, which are indicative of overall themes (Watts & Stenner, 2012). Thus, the participant is considered the variable in Q studies.

William Stephenson developed Q methodology to measure the subjective objectively” (Ramlo & Newman, 2011), as he recognized that subjective behaviors were being inaccurately measured in an objective manner. As stated by Watts and Stenner (2012), Q methodology aims only to establish the existence of particular factors or viewpoints and shows patterns among opinions that cannot be determined based on purely qualitative (Rajé, 2007) or quantitative methods. Q methodology is an adaptation of the traditional factor analysis, in which the attention is on the subjective viewpoints of participants instead of identifying patterns between objective variables. Each pattern identified is represented as a single factor emerging from the participant Q sorts and factor analysis (Davis, 1999). Factors, and the profiles that emerge from them, are considered to be more stable than individual variables (Ramlo & Newman, 2011). The results of a Q study seek to identify varied information (Stephenson, 1935; Stainton Rogers, 1995) and provide insight into participants’ viewpoints (Barry & Proops, 1999). Thus, Q methodology is interested in the constructions of the statements, instead of the participants that construct the Q sort (Stainton Rogers, 1995).

Q methodology has been utilized in numerous fields to understand and systematically analyze subjectivity (Barry & Proops, 1999; Brown, 1993) in a holistic fashion. Results of a Q methods study provide a wealth of information, including high levels of content and descriptions, which can also be used to build and test theories (Ramlo & Newman, 2011), and can serve as a catalyst for discussion among various stakeholders (Militello & Benham, 2010).

Q analysis examines three statistical elements to identify a set of viewpoints: correlations between Q sorts, extracted factors, and factor rotation (Donner, 2001). Each of these elements provides researchers with a means to investigate similarities and differences among diverse viewpoints on a topic (van Exel & de Graaf, 2005). Due to the abductive nature of Q methodology, the use of an exploratory factor analysis was a result, which identifies subjectivities (van Exel & de Graaf, 2005). The dissimilarities between participants are not of interest, as Q methodology is not a test of difference (Watts & Stenner, 2012). The factor analysis employed for a Q study correlates participants over the number of Q sorts, instead of a traditional R analysis which correlates statements over the participants (Duenckmann, 2010; Stephenson, 1933). Based on Q methodology’s characteristics, it was clear that this method would be of benefit for this study’s objectives.

Research Methodology

Interviews and Focus Groups

Data for this study was collected in multiple rounds. First, we conducted interviews and focus groups within the Districts of Jessore & Rajshahi. Participants in these focus groups were young adults, aged 18-35, who self-identified as current or aspiring entrepreneurs. During these interviews, participants were asked about their own experiences with business creation in their local community. They were also asked what they believed was needed to increase the number of young adults creating businesses. Findings were recorded to give a general sense of perceived entrepreneurial challenges, which also guided subsequent data collection actions and the creation of a Q set.

Surveys

To investigate how young entrepreneurs perceived their own business creation abilities, we created paper surveys, written in Bengali, which were distributed to aspiring entrepreneurs that recently completed a 5-day entrepreneurship training workshop. Questions asked about their perceived entrepreneurial ability, fear of business failure, and availability of entrepreneurial opportunities in their community. To compare these responses to nationwide averages, some of these questions were the same as those from the 2011 Bangladesh GEM report (Karim & Hart, 2011). Survey questions asked participants to indicate their agreement with statements about entrepreneurship opportunities in their community and their own skills when creating a business. Options of response for these survey questions were Yes, No, Don’t Know and Decline to Answer.

Q Methodology

Development of Q set

Using responses from surveys, interviews, and focus groups, as well as findings from past literature, 20 Q set statements were generated for distribution into a Q sort grid, reproduced in Error! Reference source not found. The Q set contained general, yet comprehensive statements, which was essential for this study in order to make sorting less demanding for participants (McKeown & Thomas, 1988). The Q set statements also avoided complicated terminology and double negative statements, and were written in Bengali for maximum participant comprehension (Duenckmann, 2010; Watts & Stenner, 2005). Terms were not defined for the participant, as it allowed for the participant to interpret the statements based on his or her experiences (Brown, 1980; McKeown & Thomas, 1988; Ramlo & Newman, 2011; Stephenson, 1953). Thus, the Q set was structured and broadly representative of subjective perspectives of entrepreneurship in Bangladesh.

Each statement listed in Table 1 was printed on its own card to be used for sorting. All cards were consistently the same size, were white in color, and each set of statements was shuffled into a random order. Each participant was given the same Q set. Once directions from the primary researcher were received, participants were asked to sort the Q set into the Q sort grid.

| Table 1: Statements Used For Q Sort: Factors Were Translated Into Bengali To Ensure Respondents Understood All Statements | |

| No. | Statement |

|---|---|

| 1 | Fear of failure prevents many individuals in Bangladesh from starting a business. |

| 2 | There are good opportunities to start a business where I live in the next 6 months. |

| 3 | Businesses need additional access to insurance to be successful. |

| 4 | Entrepreneurs need additional access to business loans from private companies to be successful. |

| 5 | Natural disasters (i.e. flooding, cyclones) limit business opportunities in Bangladesh. |

| 6 | Local entrepreneurs need training for job skills from private companies |

| 7 | The government needs to pass additional regulations to ensure consistent quality of goods and raw materials |

| 8 | Corruption in Bangladesh significantly hinders business creation. |

| 9 | Efforts from Non-Government Organizations promote successful businesses in Bangladesh. |

| 10 | Successful entrepreneurs have a high status in society. |

| 11 | Bangladesh needs additional infrastructure to increase successful businesses. |

| 12 | Entrepreneurs need additional access to government business loans to be successful. |

| 13 | More students should study at Universities and post-high school institutions. |

| 14 | Women should not create or run businesses of their own. |

| 15 | Aspiring entrepreneurs have the skills needed to start their own business. |

| 16 | You will often see stories about people starting successful new business in the media. |

| 17 | Internet capabilities are sufficient for most businesses in Bangladesh. |

| 18 | Business owners are able to seek advice for starting or growing a business from others in their community. |

| 19 | The government creates laws that promote successful businesses. |

| 20 | Local entrepreneurs need training for job skills from the government. |

Q Sort Grid

Figure 1 shows the Q sort grid used in this study. The distribution was symmetrical and was numbered from -3 to +3, with only two statements ranked at the “most like my view” and most unlike my view poles. A majority of the items are located at zero, which is the neutral area of the Q sort grid. The forced-choice, quasi-normal distribution pushed participants to assign a rank to each statement (Watts & Stenner, 2012), which allowed for patterns to emerge across Q sorts created by participants (Watts & Stenner, 2005). Because the distribution is prearranged, the Q set statements are automatically standardized. Thus, there wasn’t an incorrect way for participants to assign the Q set statements to a particular area on the Q sort (Ramlo & Newman, 2011). The distribution’s kurtosis was platykurtic, due to the participants’ existing knowledge on the topic (Watts & Stenner, 2012).

Procedure

As guided by Watts & Stenner (2012), participants complete a Q sort by allocating all statements in the Q set relative to one another. Statements they feel more in agreement with are awarded a higher ranking, and distributed at the right-hand end of the grid. Statements they feel more negatively about are assigned a lower ranking, at the left-hand side of the grid. Each statement is ranked in relation to the other statements and placed upon the Q sort distribution, which indicates why the participant is viewed as the variable in Q studies. Statements in a single column have the same score, and the order within each column is not of importance. This was conveyed to all participants while completing their individual Q sort.

To initiate the Q sort process, the primary researcher verbally stated the research objective, as recommended by Donner (2001), and instructed participants throughout the Q sort process, including the procedure described above. The researcher also presented the Q set statements and the Q sort distribution at the beginning of the data collection stage. Q set statements were sorted by participants into respective categories (agree, disagree, neutral), and then each statement was ranked within the Q sort distribution. The participants took an average of 20 minutes to complete the Q sort. After participants completed the Q sorts, the statements were taped onto the physical Q sort grid and statement numbers were recorded in Microsoft Excel. Q sorts were correlated and analyzed using PQMethod software.

Participants

Twenty-eight aspiring young adult entrepreneurs were purposively recruited to complete the paper surveys and Q sort. These participants were chosen for this study based on the importance of gaining these individual viewpoints, as recommended by past literature (Brown, 1980; McKeown & Thomas, 1988; van Exel & de Graaf, 2005; Watts & Stenner, 2012). These participants were anticipated to provide interesting and diverse viewpoints for this study, providing a balanced perspective. All 28 participants completed the paper survey, of which 27 successfully completed the Q sort. Based on the subjective elements of Q methodology, a smaller number of participants are needed than a typical R study (Barry & Proops, 1999; Donner, 2001) because “…we are looking for our participants to impose their own meanings onto the items throughout the sorting process and to infuse them with personal, or psychological, significance” (Watts & Stenner, 2012). A smaller number of participants also heightens the consistency and quality of the data when using Q methodology (Rajé, 2007).

Results

Findings from Interviews and Focus Groups

Error! Reference source not found, shows responses to the question what is needed to promote additional business creation in Bangladesh, as well as the percentage of participants that mention each need statement. Training of job skills (54%) was the most frequent response, mentioned by over half of all participants. This finding is in line with the Bangladesh GEM Report, which found only 27.3% of respondents answered affirmatively to the statement I have the skills, knowledge, and experience necessary to start a business (Karim & Hart, 2011). Additional job opportunities for youth (9%) were also frequently mentioned by participants, indicating limited opportunities for building competencies while working. These findings align with past research, which has cited inadequate education and job training as a significant deterrent to new business creation (Table 2) (Hossain, 2006; Shohel, 2015).

| Table 2: Most Frequent Responses (N=56) To The Question "What Is Needed To Promote Additional Entrepreneurship In Bangladesh?” | |

| Need Statement | Percentage of Participants |

|---|---|

| Training of job skills | 54% |

| Additional access to business loans | 48% |

| Improved infrastructure or transportation | 13% |

| Access to additional customers | 9% |

| Additional job opportunities for youth | 9% |

| Government-subsidized business loans | 4% |

| Regulation of suppliers to improve quality control | 4% |

| Additional computers and technology | 4% |

| Price controls | 4% |

| Note: Percentages do not add up to 100% due to some participants mentioning multiple statements. | |

Participants frequently cited access to capital and financing as needed for additional entrepreneurship, and the second most frequent need statement was additional access to business loans (48%). Additional responses were more specific and mentioned government-subsidized business loans (4%) as needed. During interviews and focus groups, many respondents mentioned the availability of microcredit and small-scale lending, as well as using these services previously (Afrin et al., 2008). However, in many instances, these loans were too small to provide sufficient capital needed for expansion. Some mentioned the availability of private business loans. However, lack of credit history and loan monitoring within Bangladesh means these loans carry very high interest rates (due to elevated risk of non-repayment) and are unaffordable to most of the entrepreneurs interviewed.

Additional institutions were also cited as important to increasing business creation, though they were less frequently mentioned than the training and finance topics mentioned above. There was no single category or focus for these needs statements, and responses included improved infrastructure or transportation (13%), Regulation of suppliers to improve quality control (4%), and access to additional computers and technology (4%).

Survey of Entrepreneur Capabilities and Attitudes

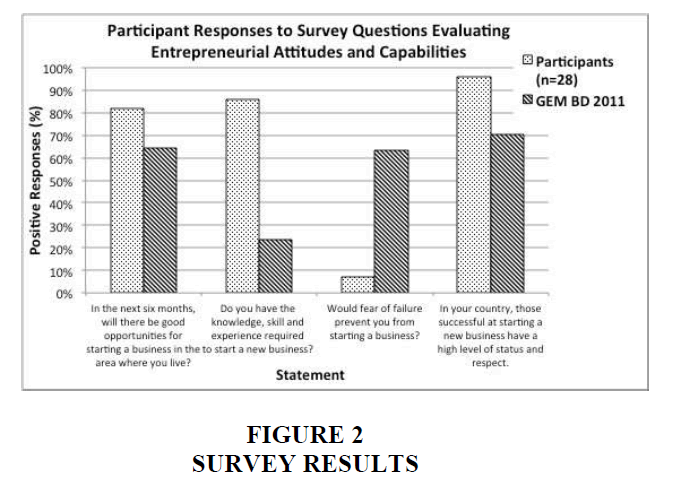

Figure 2 shows results from the survey compared to similar questions included in the 2011 GEM report for Bangladesh (Karim & Hart, 2011). Over 80% of participants believed there were good business opportunities in their community, and almost all believe successful entrepreneurship was well respected. Additionally, respondents were very confident of their own entrepreneurial capabilities and unlikely to have fear of failure deter them from starting a business. These results strongly contrast findings from Karim & Hart (2011), and show much more optimistic attitudes towards entrepreneurship, as well as perceived opportunities and capabilities. It is currently unclear whether this is due to entrepreneurial attitudes improving since publication of this previous report, or whether young adults have different perceptions than the general Bangladeshi population.

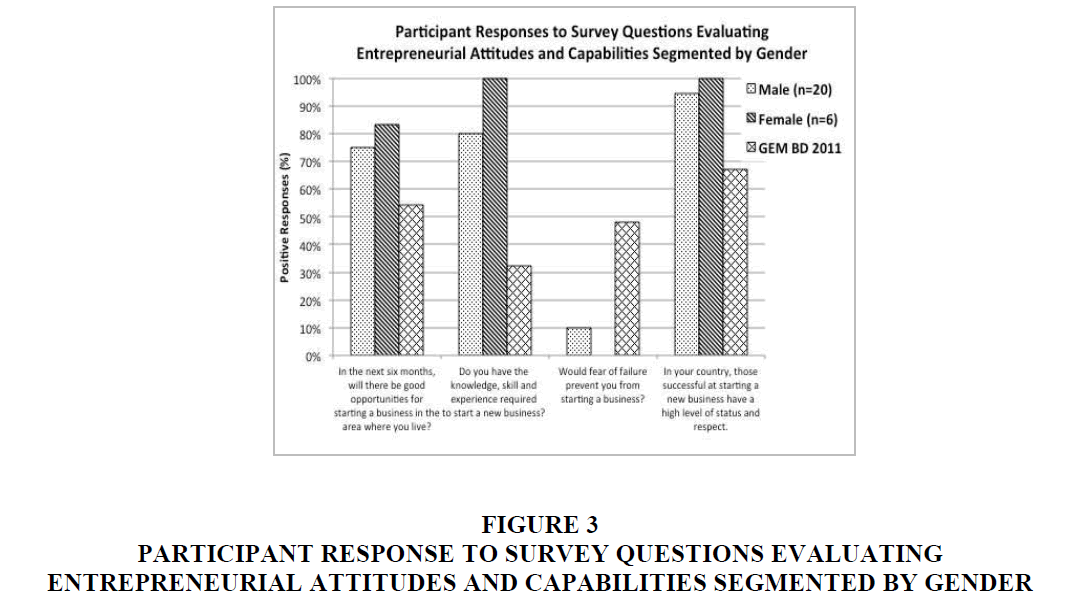

There was not a significant difference in between the average of responses from male (n=22) and female (n=6) participants (Error! Reference source not found). Both genders believed there were good entrepreneurial opportunities, and that they had the capabilities to successfully start a business. These results are interesting when considered in the context of previous literature. Past research has identified significant cultural stigmas to female entrepreneurship and business ownership. This could suggest that women would have less optimistic entrepreneurial attitudes than their male counterparts. However, results from this survey indicate this stigma might not be as prevalent for younger generations (Figure 3).

Figure 3:Participant Response To Survey Questions Evaluating Entrepreneurial Attitudes And Capabilities Segmented By Gender.

While these results indicate optimistic attitudes towards business creation, it is possible that it does not portray a comprehensive national view. All participants for this survey lived near or around Rajshahi, and these attitudes might vary in different regions of Bangladesh. Additionally, the particularly small sample size for female respondents (n=6) does not allow for a definitive comparison of male and female responses. Additional research with a wider national scope is needed to confirm these results with more certainty.

Correlation Procedures

A correlation matrix showed the degree of agreement among each Q sort (van Exel & de Graaf, 2005) and was subjected to an exploratory factor analysis (Brown, 1993). To reduce the correlation matrix to a smaller number of factors, a principal components analysis (QPCA) was employed to identify a subset of participants that share similar views. QPCA was used to create combinations that maximized the total variance and isolated common factors. Eigenvalues were calculated with QPCA, which helped to further identify significant factors (Donner, 2001). As a result, factors that had high factor loadings were used to group participants together into a single group (Ramlo & Newman, 2011). High factor loadings also demonstrated a lean toward objectivity, while low factor loadings tended to signal subjectivity. Factor arrays were also intercorrelated (Watts & Stenner, 2012).

Extracted Factors and Rotation

The factor analysis described above identified sets of individual Q sort responses with similar viewpoints (referred to as factors in this paper). After examination of eigenvalues for factor selection (Barry & Proops, 1999; Duenckmann, 2010), four factors were found to adequately represent diverse viewpoints on this topic. The four factors explained 63% of the variance and accounted for 24 out of 27 participants. The remaining three participants were confounded, and each significantly loaded on more than one factor. These three confounded Q sorts were eliminated from the analysis at this stage, as consistent with other Q sort studies (Raje, 2007).

For each factor identified, a factor exemplifying Q sort shows the ideal Q sort to represent all responses within that factor (Shinebourne & Adams, 2007). It shows the ranking of each statement within that factor (ranging from Strongly Disagree at -3 to Strongly Agree at +3). The factor exemplifying Q sorts for each of the four extracted factors are reproduced in Table 3. Each column represents a single factor, with the number representing the statement’s position on a single Q sort grid for that factor. Viewing the table by row will show how a single statement ranked across all factors. Based upon the ranking of statements within the factor exemplifying Q sorts, we further analyzed each factor’s characteristics for notable similarities and differences.

| Table 3: Factor Exemplifying Q Sorts For Four Extracted Factors | |||||

| No. | Statement | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fear of failure prevents many individuals in Bangladesh from starting a business. | 2 | 2 | -2 | 3 |

| 2 | There are good opportunities to start a business where I live in the next 6 months. | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | Businesses need additional access to insurance to be successful. | 2 | 3 | 1 | -2 |

| 4 | Entrepreneurs need additional access to business loans from private companies to be successful. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | Natural disasters (i.e. flooding, cyclones) limit business opportunities in Bangladesh. | -1 | 0 | 2 | -2 |

| 6 | Local entrepreneurs need training for job skills from private companies | 2 | 1 | -1 | -1 |

| 7 | The government needs to pass additional regulations to ensure consistent quality of goods and raw materials | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 8 | Corruption in Bangladesh significantly hinders business creation. | 1 | 2 | -1 | 1 |

| 9 | Efforts from Non-Government Organizations promote successful businesses in Bangladesh. | -2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | Successful entrepreneurs have a high status in society. | 0 | -1 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 | Bangladesh needs additional infrastructure to increase successful businesses. | 3 | -2 | -2 | -1 |

| 12 | Entrepreneurs need additional access to government business loans to be successful. | 3 | -3 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | More students should study at Universities and post-high school institutions. | -2 | -1 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | Women should not create or run businesses of their own. | -3 | -1 | -3 | -3 |

| 15 | Aspiring entrepreneurs have the skills needed to start their own business. | -3 | -2 | -2 | 0 |

| 16 | You will often see stories about people starting successful new business in the media. | -2 | 0 | -3 | -1 |

| 17 | Internet capabilities are sufficient for most businesses in Bangladesh. | -1 | -3 | 0 | -3 |

| 18 | Business owners are able to seek advice for starting or growing a business from others in their community. | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 19 | The government creates laws that promote successful businesses. | -1 | -2 | -1 | -2 |

| 20 | Local entrepreneurs need training for job skills from the government. | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Factor 1: Resource Seekers

Demographics

Eight participant Q sorts significantly and purely loaded on Factor 1. Six males and two females comprised of the eight participants, ranging in age from 26 to 53. The average age represented is 34.5 years old. Factor 1 explained 24% of the study’s variance.

Interpretation

These participants are looking for an increase in availability of resources, such as government loans (12:3), private loans from companies (4:1), and insurance (3:2). Job training from private companies (6:2) and the government (20:1) are also sought, as entrepreneurs feel as if they do not have the skills that they need to run a business (15:-3). Such skills are not obtained through additional education, however, as participants believed continued education is not of importance to starting and sustaining a successful business (13:-2). NGOs are also not helpful in this endeavor and do not promote business growth in Bangladesh (9:-2).

The infrastructure of Bangladesh is also of concern, which must be strengthened before the number of successful businesses can rise (11:3), including the increase in Internet capabilities (17: -1). Corruption in Bangladesh is also believed to halt the development of new businesses (8: 1) and laws set by the government dissuade entrepreneurs (19:-1). Successful entrepreneurs are rarely seen in the media (16:-2), leading to a possible misunderstanding within the population that entrepreneurship is a viable option for all individuals, including women (14:-3). Based on the lack of available resources, skills and exposure, there is a high fear of failure that stops many from starting a business in Bangladesh (1:2).

Factor 2: Pragmatists and Institution Critics (Bipolar Factor)

Demographics

Five participant Q sorts significantly and purely loaded on Factor 2. Three males and two females, ranging in age from 20 to 40, contributed to Factor 2’s exemplifying Q sort. The average age represented by Factor 2 is 30.6 years old. Factor 2 explained 12% of the variance.

Factor 2 represents a bipolar factor, in which two competing viewpoints are demonstrated by a single factor exemplifying Q sort. One of these viewpoints is in agreement with this sort (denoted as Factor +2), while the other represents an opposite viewpoint (denoted as Factor -2). Thus, two interpretations of Factor 2 will be presented. It is interesting to note a gender divide for all participants that loaded significantly on this factor -- three male participants were characterized by Factor 2+, whereas three female participants were characterized by Factor -2.

Interpretation

Factor +2 represents the Pragmatists which were demonstrated by the males in this factor. Participants defining this factor voiced their concerns with the Bangladeshi government’s support of entrepreneurship. Access to insurance (3:3), corruption (8:2), and additional regulations for quality control (7:3) were of highest concern. Current governmental laws are viewed as a hindrance for entrepreneurs (19:-2) and additional loans are not needed from the government (12:-3), however, the infrastructure is considered stable (11:-2). NGOs are providing help to businesses (9:1), but private companies should provide more loans (4:1). Internet capabilities must also be heightened to adequately compete in business (17:-3).

Entrepreneurs do not have a high status in Bangladesh (10:-1), but there are plenty of opportunities to start a business (2:2) regardless of gender (14:-1). Students are not in need of additional education to run a business (13:-1), but private companies should provide additional job skills (6:1). Despite these optimistic views, a fear of failure is still evident (1:2).

Factor -2 represents the Institution Critics which was demonstrated by the females in this factor. From this perspective, the government does not develop laws that support entrepreneurs (19:2), but there is not a need to pass additional regulations for quality products (7:-3). Overall, the infrastructure of Bangladesh should be improved (11:2). Private loans (4:-1) and job training (6:-1) are not expected from private companies and NGOs are not considered helpful to entrepreneurs (9:-1). However, studying at a university is valued (13:1). Access to government loans is expected (12:3), but access to insurance is not an issue (3:-3). Overall, the level of corruption is viewed to be low in Bangladesh (8:-2).

Entrepreneurs are viewed to be confident in their endeavors, as the perceived fear of failure is low (1:-2). The high level of confidence is due to the high status entrepreneurs have in society (10:1). Despite the high level of enthusiasm, participants representing Factor -2 stated that there are not many opportunities to start a business in Bangladesh (2:-2).

Factor 3: Entrepreneurship Enthusiasts

Demographics

Four participant Q sorts significantly and purely loaded on Factor 3. Three males and one female were identified, ranging in age from 22 to 33. The average age represented by Factor 3 is 26.5 years old. Factor 3 explained 12% of the variance.

Interpretation

Participants defining this factor indicated a high level of excitement toward entrepreneurship opportunities in Bangladesh, but were aware of governmental and environmental obstacles. Participants indicated that successful entrepreneurs have a high status in society (10:3), but are rarely showcased in the media (16:-3). It is believed that there are many opportunities for all entrepreneurs, including women (14:-3), to start a business (2:2), however the fear of failure is high (1:-2). This is due to the need for entrepreneurs to develop additional skills for success (15:-2), which is expected to be gleaned from government agencies (20:2) and other business owners (18:1), but not from private companies (6:-1). Natural disasters could limit the success of a business (5:2) and the need for additional insurance is essential (3:1).

Bangladesh’s infrastructure is deemed to be acceptable (11: -2) and corruption is considered to be low (8:-1) by the participants representing Factor 3, but the government’s laws are viewed to hinder successful businesses (19:-1). The government also needs to pass regulations for the use of quality goods and materials (7:3). Access to governmental loans for a business’s startup is also encouraged (12:1).

Factor 4: Achievement Minded

Demographics

Seven participant Q sorts significantly and purely loaded on Factor 4. All seven were male, ranging in age from 18 to 34. The average age represented by Factor 4 is 24.9 years old. Factor 4 explained 15% of the variance.

Interpretation

Participants defining this factor identified the risky, yet rewarding stature of entrepreneurs in Bangladesh. While a high fear of failure is evident (1:3), a draw to the high status entrepreneurs have (10:3) in Bangladesh is a motivation. Even though successful entrepreneurs are not shown in the media (16:-1), participants indicated that there were many opportunities for new businesses where they live (2:2) regardless of gender (14:-3).

While natural disasters are not of concern (5: -2), a lack of sufficient internet capabilities are viewed to be crucial to running a successful business (17:-3). Efforts from various NGOs help to support the creation and growth of businesses (9:1), but government corruption (8:1) and the creation of unhelpful laws block development (19:-2). Laws must also be passed to heighten the quality of produced goods and raw materials (7:2). A growth in infrastructure is not needed (11:- 1) and skills should not be developed with help from private companies (6:-1), but from the government (20:2). Government loans are also needed (12:1) along with additional access to insurance (3:-2).

Discussion And Conclusions

Beyond identifying prevalent perspectives, we can gain additional insight by comparing all factors simultaneously. This allows us to identify perceptions that are widely prevalent amongst young adults in Bangladesh. Notable observations from this analysis are elaborated below.

One theme prevalent in all factors pertains to skepticism about government’s ability to promote entrepreneurship. This can be seen with statement 19 (The government creates laws that promote successful businesses), and all factors assigned this statement a negative score. Further, for statement 7 (The government needs to pass additional regulations to ensure consistent quality of goods and raw materials), three of four factors assigned this statement a score of +2 or +3, indicating strong agreement with this statement. These findings indicate that young people tend to agree with previous investigations, which have identified government’s limited assistance to new businesses in Bangladesh.

Further, the need for additional training was prevalent amongst all factors. Statement 15 (Aspiring entrepreneurs have the skills needed to start their own business) received a score of -2 or -3 for all but one factor. This matches one of the most prevalent themes to come out of the interviews and focus groups section of this project. However, there was no overall trend for where participants believed this training should come from. While most factors believed government should provide some more training (Statement 20), this viewpoint is closer to neutral than some others. Results were even more mixed when looking at private companies (Statement 6). Ultimately, participants believe additional training is important, but are unsure where this training should come from.

Finally, a surprising find from the Q sort was the widespread perception of gender equality amongst young adults. For statement 19 (Women should not create or run a business of their own), all factors disagreed with this statement, with 3 factors strongly disagreeing (with a score of -3). This suggests that young adults may be more open to female entrepreneurship than other population segments, and that female entrepreneurship might approach parity in the future.

Validity and Reliability of Q Methodology

Q methods studies are considered valid when the Q set is exhaustive and when statistical tools are used to identify factors. The Q sort also poses as a more involved method of data collection, as participants spend more time considering the statements than a traditional R study, leading to more valid data. Item order effects are not found when the Q sort is completed manually with a shuffled Q set (Serfass & Sherman, 2013).

Q methodology’s output is considered rigorous, as subjective viewpoints are the main focus of the study (Stephenson, 1953). Reliability of Q methodology based on subjectivity also tends to be high (Ramlo & Newman, 2011). Q sorts have few response biases, such as acquiescence, midpoint, or extreme responses, as ranking eliminates such issues (Block, 1978), as well as less research bias as compared to pure qualitative studies (Ramlo & Newman, 2011).

Limitations

Previous Q studies have recommended the use of a post-sorting interview; as such data increases the in-depth quality of the overall study (Brown, 1980; Ramlo & Newman, 2011; Watts & Stenner, 2012). However, due to translator availability and wide geographical range of respondent hometowns, it was not feasible to interview respondents after completion of the Q sort. Further, many of the insights we would capture from these post-sort interviews were already received from pre-sort interviews and focus groups conducted before this Q sort. Future studies on this topic, especially those that utilize the same Q set or don’t employ pre-sort interviews and surveys, could utilize a post-interview to gain more insight from participants.

A rule of thumb outlined by Watts & Stenner (2012) recommends that the number of Q set statements should be twice as large as the number of participants, and that the number of participants should be less than the total number of Q set statements. In support, Barry & Proops (1999) found that 36 statements tend to lead to the most convenient number of statements for both the researcher and participant, and also identified that larger sample sizes do not benefit Q studies. However, due to variability in educational level for respondents, we elected to limit the number of statements at 20. This was decided in order to prevent respondents from getting overwhelmed and distracted by a larger amount of statements, lowering data quality.

Further, despite the lower number of statements in this study, Donner (2001) asserts that statements are not the focus of the study, but the patterns and underlying criteria are of more interest. Studies using Q methods are not meant to be generalized to the overall population, but implications can be made (Rajé, 2007; Watts & Stenner, 2012).

Conclusions

This study investigated young adult perceptions towards entrepreneurship in Bangladesh. While the importance of entrepreneurship as a driver of economic development is well established, much of past research has focused on quantitative measures, overlooking perceptions that can be important to entrepreneurial actions. The study described in this paper used multiple rounds of data collection to investigate these perceptions. First, entrepreneurs and community leaders identified what they believed is needed to encourage additional venture creation. Lack of credit and adequate job training emerged as challenges to sustained business creation. Next, participants completed paper surveys explaining their own attitudes towards entrepreneurship. Despite the many identified needs, most still believed that there was good business opportunities and those they had the abilities to start sustainable businesses.

Finally, a Q Sort completed by 27 Bangladeshi young adult entrepreneurs identified four distinct factors. While some themes were observed in multiple factors (like the need for additional job training, or the lack of aversion to female business ownership), each factor represents a different set of variables common to a group of participants in this study. These findings give a greater understanding of entrepreneurial perceptions and attitudes for aspiring entrepreneurs in Bangladesh. It further shows that there is no single approach that will address all challenges to additional business creation and growth.

While the findings from this study are solely indicative of entrepreneurship within Bangladesh, the methodology used in this study can serve as a model for future research studies. Perceptions of entrepreneurship are important for new venture creation in all economic environments. The research methods used in this study can be applied to other countries where there is limited knowledge of attitudes towards entrepreneurship. This would result in a deeper understanding of what is needed to promote business creation and economic growth in these regions.

References

- Ács, Z.J., Szerb, L., & Lloyd, A. (2018). The global entrepreneurship and development index. In Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index 2018. The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute.

- Afrin, S., Islam, N., & Ahmed, S.U. (2009). A multivariate model of micro credit and rural women entrepreneurship development in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 3(8), 169.

- Asadullah, M.N., Savoia, A., & Mahmud, W. (2014). Paths to development: Is there a Bangladesh surprise? World Development, 62, 138-154.

- Azim, M.T., & Akbar, M.M. (2010). Entrepreneurship education in Bangladesh: A study based on program inputs. South Asian Journal of Management, 17(4), 21.

- Barry, J., & Proops, J. (1999). Seeking sustainability discourses with Q methodology. Ecological Economics, 28(3), 337-345.

- Brown, S.R. (1980). The forced-free distinction in Q technique. J Educational Measurement, 8(4), 283- 287.

- Brown, S.R. (1980). Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science. Yale University Press.

- Brown, S.R. (1993). A primer on Q methodology. Operant Subjectivity, 16(3/4), 91-138.

- Chowdhury, M.S. (2007). Overcoming entrepreneurship development constraints: The case of Bangladesh. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 1(3), 240-251.

- Davis, T.C. (1999). Revisiting group attachment: Ethnic and national identity. Political Psychology, 20(1), 25-47.

- Davis, C.H., & Michelle, C. (2011). Q methodology in audience research: Bridging the qualitative/quantitative divide ? Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, 8(2), 559-593.

- Donner, J.C. (2001). Using Q-sorts in participatory processes: An introduction to the methodology. Social Development Papers, 36, 24-49.

- Duenckmann, F. (2010). The village in the mind: Applying Q-methodology to re-constructing constructions of rurality. Journal of Rural Studies, 26(3), 284-295.

- Gnyawali, D.R., & Fogel, D.S. (1994). Environments for entrepreneurship development: key dimensions and research implications. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(4), 43-62.

- Guerrero, M., Rialp, J., & Urbano, D. (2008). The impact of desirability and feasibility on entrepreneurial intentions: A structural equation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4(1), 35-50.

- Guha, R.K., & Al Mamun, A. (2016). Youth employment and entrepreneurship scenario in rural areas of Bangladesh: A Case of Mohammedpur West Union.

- Heitzman, J., & Worden, R., eds. (1989). The banking system. Bangladesh: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. 109-112.

- Hossain, D.M. (2006). A literature survey on entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship in Bangladesh. Southeast University Journal of Business Studies, 2(1).

- Huq, S.M.M., Huque, S.M.R., & Rana, M.B. (2017). Entrepreneurship education and university students’ entrepreneurial intentions in bangladesh. Entrepreneurship: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications, 221.

- Isenberg, D.J. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard business review, 88(6), 40-50.

- Karim, M., & Hart, M. (2011). Bangladesh 2011 Monitoring Report. London, UK: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

- Khondkar, M. (1992). Entrepreneurship development and economic growth: The Bangladesh case. Dhaka University Journal of Business Studies, 13(2), 199-208.

- Lee, S.M., & Peterson, S.J. (2000). Culture, entrepreneurial orientation, and global competitiveness. Journal of World Business, 35(4), 401-416.

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2007). Entrepreneurship for social impact: Encouraging market access in rural Bangladesh. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 7(4), 493-501.

- Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Entrepreneurship in and around institutional voids: A case study from Bangladesh. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 419-435.

- McGee, J.E., Peterson, M., Mueller, S.L., & Sequeira, J.M. (2009). Entrepreneurial self‐efficacy: refining the

- measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(4), 965-988.

- McKeown, B., & Thomas, D. (1988). Q Methodology. Newbury Park: CA, Sage.

- Militello, M., & Benham, M.K.P. (2010). Sorting out collective leadership: How Q-methodology can be used to evaluate leadership development. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(4), 620-632.

- Murata, A., & Nishimura, N. (2016). Youth employment and NGOs: Evidence from Bangladesh. JICA Research Institute, 124, 1-10.

- Nawaz, F. (2009). Critical factors of women entrepreneurship development in rural Bangladesh. Bangladesh Development Research Working Paper Series, 12.

- Rahman, M.M., Ibrahim, M.H., & Miah, A.S. (2000). Problems of women entrepreneurship development: A study of grameen bank finance on some selected areas. Islamic University Studies (Part-C), 3, 124-128.

- Rajé, F. (2007). Using Q methodology to develop more perceptive insights on transport and social inclusion.

- Transport Policy, 14(6), 467-477.

- Ramlo, S.E., & Newman, I. (2011a). Classifying individuals using Q methodology and Q factor analysis: Applications of two mixed methodologies for program evaluation. Journal of Research in Education, 21(2), 20-31.

- Ramlo, S.E., & Newman, I. (2011b). Q methodology and its position in the mixed-methods continuum. Operant Subjectivity: The International Journal of Q Methodology, 34(3), 172-191.

- Serfass, D.G., & Sherman, R.A. (2013). A methodological note on ordered Q-sort ratings. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(6), 853-858.

- Sharma, M., & Zeller, M. (1997). Repayment performance in group-based credit programs in Bangladesh: An empirical analysis. World Development, 25(10), 1731-1742.

- Shinebourne, P., & Adams, M. (2007). Q-methodology as a phenomenological research method. Existential Analysis, 18(1), 103-116.

- Shohel, M.C. (2015). Challenges for education in Bangladesh. Retrieved August 26, 2016, from http://www.culturacritica.cc/2015/04/challenges-for-education-in-bangladesh/?lang=en

- Stainton Rogers, R.S. (1995). Social Psychology: A Critical Agenda.

- Stephenson, W. (1953). The Study of Behavior: Q Technique and Its Methodology. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Van Exel, & de Graaf (2005). Q methodology: A sneak preview. Retrieved on March 12, 2018.

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2005). The subjective experience of partnership love: A Q methodological study. British Journal of Social Psychology, 44(1), 85-107.

- Watts, S., & Stenner, P. (2012). Doing Q Methodological Research. London, Sage. World Bank Open Data (2013). Washington, DC.