Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 4

An Investigation of the Impact of Post-Apartheid Informal Economy Policies on Informal Traders in South Africa

Trisha Ramsuraj, Durban University of Technology

Abstract

South Africa has one of the highest unemployment figures in the world. Despite the high figures there is low penetration of informal economy when compared not only to other African countries but the rest of the world. This is mainly attributed to the historical background of the country. The apartheid government that was in place before 1994 had zero tolerance towards informal traders and enacted laws and policies that did not favor the sector.In recent times the South African government has been revising the laws and putting in place policies that encourage the growth of the informal economy. A number of studies have shown that eThekwini Municipality has one of the best policies in South Africa which target the informal economy. The results from the study show that there is lack of awareness of the informal economy policies by the informal traders. Most of the informal traders are not registered and they do not see any benefits of doing so. There is still hostility between the informal and formal traders. Informal traders highlighted a number of challenges they face every day, such as lack of shelter, storage space and running battles with law enforcers. There is need to revise the funding and implementation strategy for informal traders or small businesses in South Africa. This study expands the conceptualization of informal business policy and strategy. Implications for theory and practice are offered. Additionally, limitations and future research directions are discussed.

Keywords

Informal Traders, Informal Sector, Government Policy, Informal Economy, Small Businesses, SMME, Entrepreneurship, Durban

Introduction

Informal trading refers to the commercial activities of individuals and/or groups engaged in the selling of legal goods and services within public and private spaces, which are commonly regarded as unorthodox in the conduct of such activities. Often it is loosely organized and not always registered as a structured business (Fredström et al., 2020). In its most simple form, this type of trading takes place on streets and pavements, on private land, which is mainly used as the place of residence of the merchant and appears to require little more capital than the actual goods and services to be exchanged. Governments and municipalities in South Africa and elsewhere have a number of policies that have direct and indirect effects on informal sector operations.

The informal sector arose as a development concern and a focus for a growing number of researchers and international institutions, especially the International Labour Organization (ILO) in the 1970s and has been growing rapidly since then. This is due to economic reform in many parts of the world, including South Africa (Portes, 1989).The first world recessions in the years 1974-75 and 1980-83 caused many people to lose their employment in the formal economy and, as a result, some of them entered the informal sector. According to Portes et al. (1989), “the final and important reason for the growth of the informal sector results from the effects of the economic crisis since the mid-1970s throughout the world.”

The informal economy in the world employs a large number of people. Some of the unskilled workers who cannot be hired in the formal economy are absorbed by the informal economy and thus contribute to a decrease in unemployment. South Africa's unemployment rate is about 27%, which is very high relative to many developed countries (Stats SA, 2019). The informal economy provides opportunities to absorb a large percentage of unemployed and sometimes unskilled workers. However, despite these high percentages of unemployed people, South Africa has a relatively low penetration of the informal economy. The informal economy contributes about 10% of South Africa’s gross domestic product, which is very low when compared to most other African countries and developing nations (Valodia, 2006; Stats SA, 2016). One of the major hindrances of the penetration has been the historical background of the country (Valodia, 2001). The apartheid governments that were in power before 1994, enacted policies and laws that was against informal trading. However, after 1994 there was a relaxation of some of the apartheid laws. After recognizing the ability of the informal economy to add to the gross domestic product and minimize unemployment, the South African government adopted laws and policies that aim to promote the informal economy.

In South Africa, “most informal businesses are small, one-man operations and include subsistence farmers, hawkers, street vendors, home businesses, backyard manufacturers, taxiowners, craft and curio makers, moonlighters and even black marketers.” (Pillay, 2008:22). Drug dealers, shebeen queens, prostitutes (sex workers), and street trading stand out amongst the most practised and regular informal economic activities both in many countries and in South Africa but these types of business are either illegal or on the borderline of being so. These types of business do not form part of this study.

In spite of government support, the informal economy has only been rising slowly. It is therefore important to examine the reasons why the sector is still contributing less than expected to the growth of the economy as a whole. This study aims to investigate the effects of the Government of South Africa's policy reform on the informal economy with specific reference to the eThekwini metropolitan municipality in the KwaZulu-Natal Province.

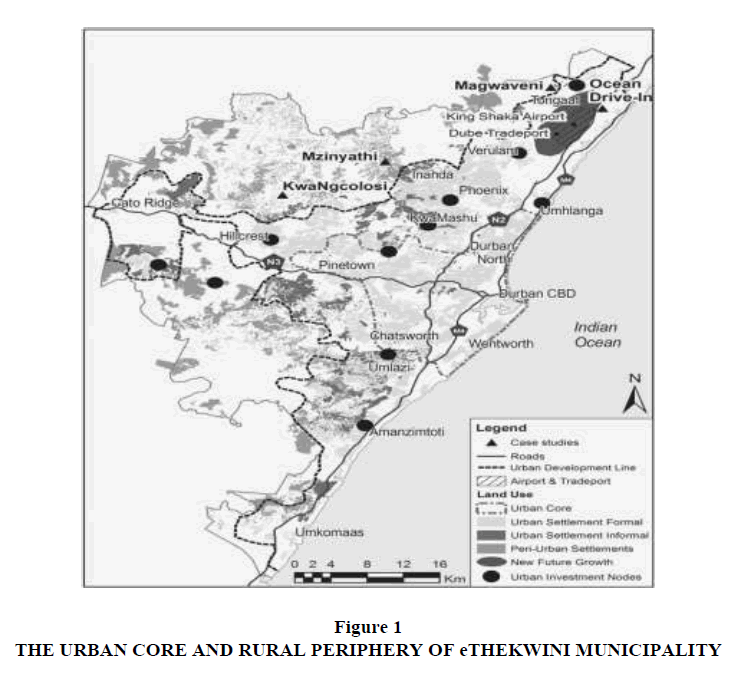

eThekwini Municipality

eThekwini Municipality is one of the largest cities in South Africa. It consists of urban and peri-urban areas. The structure of the city is shown in the map below in Figure 1 Source: Sutherland et al., 2015. eThekwini Municipality is one of the first cities in South Africa that embraced the informal economy and included it in its planning (EM, 2019). In 2001 it launched its first informal economy policy called Durban’s Informal Economy Policy (Durban Unicity Council, 2001). Therefore, it is of interest to investigate the impact of policy change on the informal economy. Informal traders are attracted to the city because of its large economy and the economic opportunities that the city offers as well as the fact that it has historically a lower crime rate than most other cities (EM, 2019).

Informal traders conduct a wide range of enterprises. Street vendors, who sell a wide range of products and services from flowers to sheep to hair salons, make up the most visible components of this sector. A large number of backyard activities such as knitting, vehicle repairs, panel beating, hair care, photography, artistic painting, masonry and other enterprises are also undertaken.

History of the Informal Economy in SA

The South Africa economy has a history of not tolerating the informal sector by employing restrictive laws that stifle its growth. The laws during the apartheid era were crafted specifically to demarcate by race. For example, ‘white’ people were protected so that they managed to get the best jobs (Nel, 1999). “The policies launched under apartheid had a particularly negative influence on African and other black people (term collectively used to refer to Africans, Asians and ‘Coloureds’). Skilled jobs were denied to them and there was an imbalance in state expenditure in favour of whites and non-Homeland areas” (Nel, 1999). This was the reason for the major financially uneven characteristics and isolation which caused stagnation in the development of the informal economy.

It was very common for there to be clashes between street traders and the law during the Apartheid era. An example is a clash of the coffee-cart traders in the streets of Johannesburg in the 1940s. “In the late 1940s a series of raids were made on the cart operators who were prosecuted for unlicensed trade in restricted foodstuffs.” (Beavon, 1989: 44). The laws that existed at the time allowed the government to restrict trading in the city streets. Raids and confiscation of goods were very common not only in Johannesburg but in other major cities in South Africa. This resulted in the formation of the African Council of Hawkers and Informal Businesses in 1986 in response to the harsh working conditions and unfair treatment of the informal traders.

South Africa’s Informal Economy Policies

The first national policy post-apartheid that specifically targeted the informal economy was the National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy (NIBUS) (Department of Trade and Industry, 2014). The NIBUS is driven by the Department of Small Business Development to address the development of the Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises. It seeks to offer support to informal businesses, uplift them and also support the Municipal Local Economic Development offices which are situated throughout the country. Their main target groups are the most vulnerable people in society, such as the women, youth and disabled people especially in townships and rural and semi–rural areas of South Africa. The strategy specifically targets entrepreneurs in the informal sector as this group has been identified as critical in addressing some of the key developmental goals of the Government, such as the reduction of poverty, lowering of unemployment and bringing about greater equality. This strategy was a product of wide consultations with all stakeholders in the economy ranging from the participants in the informal economy, donors, financial institutions, financial and other intermediaries, service providers, the private sector and civil society organizations (DTI, 2014).

The Municipal Systems Act (No.32) of 2000 requires that local government structures prepare Integrated Development Plans (IDPs), major tools used to transform local governments to be geared towards development within their areas of authority (RSA, 2000). The Act has mandated all municipalities in South Africa to use IDPs to drive the achievement of development goals. All the development needs of local government are to be captured in IDPs. Each IDP has a lifespan of five years. In 2015, in the IDP for eThekwini Municipality the informal economy was included as one of the strategic areas, which required attention and management. It highlighted the fact that the informal economy was a “demanding task involving demarcation of trading areas, issuing of permits, organizing traders into area committees that feed into a citywide forum, and on-going collection of rentals” (EM, 2015:220). The inclusion of the informal economy as a strategic area meant that for every budget in the next 5 years after the adoption of the IDP there would be included a certain percentage for development of the informal economy.

In the year 2020 the then Minister of Small Business Development minister Khumbudzo Ntshavheni gazetted the National Small Enterprise Amendment Bill, which aimed to further regulate the country’s small, medium and micro-enterprises (SMME) sector (BusinessTech, 2020). This bill main aim was to allow minister ombudsman to further control South African small enterprises with regard to unfair trade practices. The bill also covered the rights such as fair and unambiguous business contract, reasonable payment date and interest on late payments, disclosure of information and the right to accountability from large enterprises and organizations. Other things that were covered are the contract terms, written contracts and transfer of commercial risk to small businesses (BusinessTech, 2020).

This study focuses on public policies pertaining to informal trading in one part of South Africa, using data gathered and examined to understand the impact of Municipality policies on Informal Traders. A case study of the northern regions of eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality is used in this study. eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality is a metropolitan municipality created in 2000 that includes the old city of Durban and many surrounding towns such as Pinetown and Phoenix. eThekwini is the biggest economic contributor in KwaZulu-Natal. It is one of the 11 districts in the province.

Research Methods and Design

Published literature and qualitative data obtained from in-depth interviews with local informal traders were used to carry out the study.

In order to arrive at sound conclusions, the researcher decided to use empirical study methods involving a survey, interviews and phenomenology to gain insight into the typical experiences of the participants in order to arrive at sound conclusions. Saunders et al. (2019) state that a phenomenological study is one that attempts to understand people’s perceptions, perspectives and views of a particular situation. By looking at multiple perspectives on the same situation, the researcher can then make some generalisations on what phenomenon is like from an insider’s perspective. The phenomenological approach aims to understand and interpret the meaning that participants give to their everyday life. For example, in this case there was an effort made to understand and interpret the lived experiences of the informal traders in the geographical areas chosen for purposes of the study.

In the current study, the research was done using both the existing literature and empirical research in the northern areas of eThekwini. The study is qualitative and descriptive, investigating the impact of the eThekwini municipality policies on informal traders in a particular area of a major city. Descriptive studies are conducted to answer questions such as who, what, when where and how (Saunders et al., 2019).

The study uses a cross-sectional methodology, which involved the collection of data from a given sample of a population during a relatively short time, avoiding unduly long gaps in time. Cross-sectional methodology is said to be the most frequently used design in business management and social science research in general (Welman et al., 2005). The main reason for choosing this approach was to get as highly reliable results as possible using types of data that are very specific and precise so that future research on similar topics can draw on this study for guidance. Additionally, the study of eThekwini Municipality policies’ impact on the informal economy may be generalised to the rest of South Africa where similar conditions prevail.

Population and Sampling Strategy

The targeted population for the study was all informal traders in the northern part of eThekwini Municipality. There are estimated to be over 900 informal traders in these regions of eThekwini (eThekwini Retail Markets 2016). This study focuses on the street vendors, taxi operators, shebeen (tavern) owners and small retail shop owners, and hawkers in and around the chosen region of eThekwini. For this study, the selected sample size was the following; numbers of traders in different places: 40 in Verulam Market, 25 in Hammersdale Market, 20 in Phoenix Market, 50 in Mansel 25 Church walk Market and 30 Brookdale Market as shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Sample Size |

||

| Name of Market | Trading Facilities | No. of Participants to be recruited for research. |

|---|---|---|

| Verulam Market | 200 Stalls | 40 |

| Hammersdale Market | 130 Stalls | 25 |

| Phoenix Market | Security lights, water cleaning | 20 |

| Mansel Road | 470 stalls | 50 |

| Churchwalk Market | 129 stalls | 25 |

| Brookdale Market | 185 stalls | 30 |

| TOTAL | 190 | |

In this instance, the most suitable sampling method or procedure was found to be the purposive sampling method since the characteristics of each group in terms of the variables under study were known. Selection was based on the informed choices of the researcher not by chance. Participants were only selected if they were knowledgeable and articulate about the subject and were willing to participate in this study. It was decided to pursue this approach after due consideration of possible alternatives.

Research Instruments

The interview schedule for this investigation was divided into five main sections. The first of these included the demographic questions (sex, age, country of origin and race). The second section of the questionnaire included the investigation of the type of trade, length (timelines) of operations and registration if any of the business. The third section covered the trader’s awareness of the eThekwini Municipality’s informal policy. This section aimed to investigate how many in formal traders know about the informal sector policies and the extent to which they have heard about them. The fourth section covered the challenges that traders face in their day to day operations. It included vital matters such as financial challenges, infrastructure and the lack of skills. The final section was an attempt to find out if there are any suggestions from the traders themselves on how their businesses can be improved and what type of support they may require from the government, local or otherwise.

Results and Discussion

The results and analysis of the qualitative data are reported in this section. Table 2 represents the variety of goods and services traded in the study sample. A striking feature of the table is the large number of different products and services listed.

| Table 2 The Variety Of Goods And Services Traded In. |

|

| Goods/Services | No of Traders (%) |

|---|---|

| Accessories | 5.26 |

| Art | 0.53 |

| Automation | 0.53 |

| Beauty | 6.84 |

| Cell phones | 0.53 |

| Cigarettes | 6.32 |

| Cleaning | 1.58 |

| Clothing | 14.74 |

| Clothing and accessories | 2.63 |

| Cosmetics | 3.16 |

| Cosmetics and clothing | 0.53 |

| Food | 12.11 |

| Footwear | 0.53 |

| Fresh produce | 10.53 |

| General | 2.07 |

| Haberdashery | 2.63 |

| Hardware | 1.58 |

| Homeware | 4.21 |

| Information Technology | 0.53 |

| Meat | 4.21 |

| Media | 0.53 |

| Non-perishables | 0.53 |

| Savouries | 1.05 |

| Shoe wear | 3.68 |

| Spices | 4.21 |

| Spiritual and Herbal | 1.05 |

| Sweets | 3.16 |

| Toys | 2.63 |

| Woodwork | 2.11 |

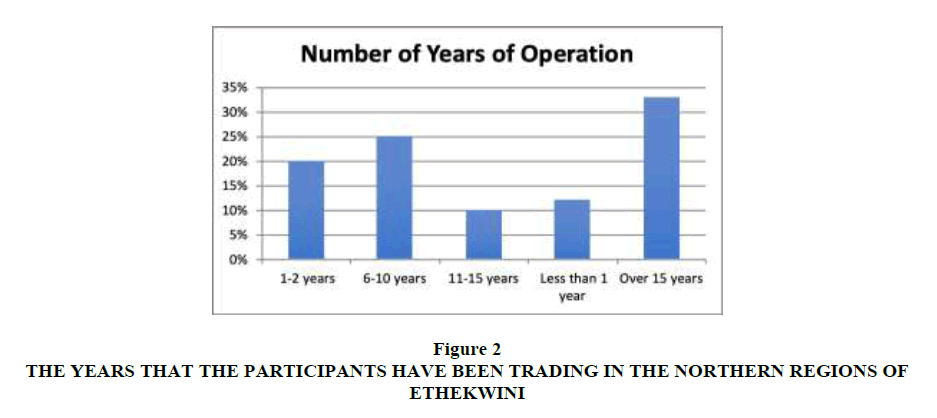

Number of Years of Operation

The sample consisted of people who have operated at the same place of business for at least a year. Approximately 80% of the participants have been operating at the same place for at least 6 years which therefore means they are likely to be well informed about at least some of the changes that have happened in formal trade. Figure 2 shows the years that the participants have been trading in the northern regions of eThekwini. It was also noted that 33% have been in the informal sector for more than 15 years. According to Lund (2014) many such traders who have been in the informal economy have made it the main part of their livelihoods and do it for a living, and they do not have any intention to look for a job in the formal economy.

Awareness of eThekwini’s informal economy policy

The majority of the respondents who were interviewed highlighted that they were not aware of the informal sector policy. They also indicated that there seemed to be little done to make them aware of the policy. Those who knew about the policy had only heard about it through the newspapers or through other traders. It was also interesting to note that according to literature in the 1990s the city of Durban made a major policy change and established a section for street management and support and allocated resources to infrastructure development for traders, but traders are not aware of this major policy shift and do not see there to be an impact. This implied that there was a communication breakdown or lack of any communication at all, between traders and the municipality.

The participants who were aware of the policy said it had no or little effect on their businesses. These findings can be linked to policy formulation which was highlighted in the literature by some authors such as Fundie et al. (2015) who noted that while the government provides a framework for the informal sector the traders are often not allowed access to, or to influence, this particular framework.

Registered business

There were very few informal businesses that were registered within the official bureaucratic framework. The reasons which were given by the traders were various with finance being the major reason that were given. The informal traders stated that they did not have the required money to register their businesses. The other reason which was pointed out by them was that their businesses were too small and had a low turnover, and therefore they saw no benefit by registering their businesses.

The municipality encouraged the informal traders to register their businesses in order for them to have advantages such as some level of stability, not having penalties to pay because of operating illegally and then being shut down. It was also interesting to note that various informal traders did not know the procedure of how to register their businesses.

Finance

Finance was highlighted as a major constraint in the operations of the informal traders. Lack of enough finance hindered them greatly from registering their businesses. This also impacted on the amount of stock they could buy and also limited the expansion of their businesses. On the cost side it was pointed out that the rentals and permits to operate were too costly for them which therefore resulted in adversely affecting their profits. Some traders operated only for limited periods such as 3 days per week but were required to pay rentals even for the days they did not trade despite the fact that their business activity would be very low during those extra days.

A number of traders highlighted that finance was affecting their growth and sometimes they are forced to reduce their stock as they would have failed to raise enough capital from their sales. One of the problems was also the performance of the general economy as people now tend to have less spending money as compared to the years gone by when people used to spend more on their services and products. This was a shared sentiment for many traders.

Infrastructure

The operating environment for street traders is not conducive with the lack of basic infrastructure being a major challenge. If better infrastructure existed there was lack of maintenance. This can be shown in the figure below which shows a blocked drainage system in one of the locations of the street traders. The street traders who were located in this place pointed out that they were exposed to flooding because of this difficulty.

The toilet facilities in business locations in most cases were not clean. The respondents further highlighted there was no access to clean water. This lack of clean toilets and water not only exposes them to diseases but also their customers. Water borne diseases such as cholera can easily become endemic in such a dystopian scenario.

Some respondents pointed out that they did not have shelter to store their goods thereby exposing the stock to heat and rain thereby causing damage. This has resulted in them at times incurring major losses. During rainy days they have low sales because they have no access to their business locations and also customers would not come, so during a rainy day they may finish with zero income for the day or not trade at all. Weather dynamics is a big problem which they could not predict. Due to poor drainage in some areas where traders are located they are forced not to trade because of flooding, which is a common feature of the climate in that part of South Africa. One of these drains in the areas of this research is shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: A Drainage System Blocked With Waste Materials At Verulam Market In The North Of Ethekwini (Picture Taken By Author)

Location

The respondents pointed out that some of the locations of the stalls are not appropriate as they are not situated in busy areas but were placed in sites where there was low business activity. They also noted that most of the public transport does not stop at the market which therefore has meant there was low foot traffic. The informal traders depend heavily on such pedestrian passing traffic for business in order to make it possible for them to capitalise on impromptu spending by customers. The respondents also mentioned that the location of some of their stalls makes it difficult for elderly people to access them because they have insufficient mobility, for example not being able to walk far. Another hindrance is that where the sheltered traders are forced to operate within the stipulated times this has led to lower sales. One of the area strading hours is limited to Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday at Verulam Market, an area where there is a busy local economy to potentially tap into.

Poor government and other support

The policy and planning documents, such as Integrated Development Plans, show that the local government takes into account the informal economy in their planning. However, this was contrary to what is actually to be perceived on the streets, as the street traders said there was really a lack of support from the government. There was lack of financial support so that the informal traders tended to use their personal savings or social grants they receive from government or borrow from other sources to finance their businesses. This hampered any opportunities for growth. It also limited the quantity of stock they could order. They also pointed to the fact (as they saw it) that there was no skills development training offered by government which also limited their growth. The lack of skills and finance were major barriers to their growth.

Political and legislative problems

The corruption of government officials and business people was mentioned by several respondents as a major challenge which reduces the possibility of favourable impacts on traders. This made their operations difficult and costly. The corruption phenomenon has seen quite a number of unregistered informal traders having illegal permits. This means there was no real incentive to have the business registered through the legal route.

According to the respondents the legislation on informal trading has not been well explained to them but they rely on their fellow traders to inform them of the rules and regulations. But this is clearly unsatisfactory. Sometimes they only get to know the municipal bylaws at too late a stage when they are charged and it is then explained to them. There was little or no accountability on the part of government officials.

Recommendations

This section provides recommendations to local government, provincial government, informal traders and other interested stakeholders on the ways to ensure the sustainability of informal traders. Listed below are specific recommendations based on the findings of the study.

Create an Awareness of the Municipality’s Informal Economy Policy

The study has shown that there is lack of trader awareness of the municipal informal economy policy and strategies. The municipal authorities should do more to create awareness and education of the informal economic policy and other initiatives for informal street traders. Educating informal traders is likely to lead traders to register their businesses which in turn will allow government to ensure that all traders are running legal businesses. The raising of awareness can be done through municipal by-laws, media channels and municipal structures such as ward committees, community development workers and councillors.

Financial Assistance for the Informal Trader

The municipality should establish financial institutions and facilities to assist informal traders in borrowing money with lower interest repayments. The financial assistance should only be available to those traders who register their business. This financial assistance will enable informal traders to expand and make a significant amount of income to sustain their business and provide for their families. This in turn helps to decrease the amount of poverty that is prevalent in the area.

Provision of Better Infrastructure

One major challenge that informal traders face is infrastructure. There are too many informal traders in relation to the stalls and sites that are available to them to operate’. The municipality can also take into consideration the number of traders that are found at any given time. When planning the stalls or sites to operate from the local government should take into consideration where there is high pedestrian traffic which creates more awareness on the part of customers. Some of the stalls are not fully utilised where they are placed; traders understandably prefer locations where there are higher volumes of people in the area at any given point in time.

There was also a lack of toilet facilities in some instances. This was posing a public health risk to not only the informal traders but also the general public as there was the possibility of serious outbreaks of diseases such as cholera. There is a need to make available running water all the time in all existing toilets and near places where there is trading in fresh foods.

In areas where there was reasonable infrastructure there was a challenge of maintenance of the facilities. The infrastructure has been suffering from lack of maintenance for some time. The municipality should make provision in its budget for servicing of the facilities and for general upkeep such as maintenance and cleaning.

It was also found that there is lack of, or seriously limited, storage facilities. This was a major cost to the informal traders as they had to go looking for alternative safe areas to keep their wares. There is a need to make provision for secure storage facilities around the areas where the traders operate. Secure storage facilities will also protect their goods from weather challenges mentioned earlier as well as theft and other forms of illegality.

The infrastructure in which the informal trader operates is critical to their survival. The informal trader creates employment for others and themselves, hence government should provide proper infrastructure within which they can conduct their business. This ought to include better toilet facilities, provision of safe storage spaces, and proper shelter to cope with any weather conditions, security from both the police (Metro and South African police services) and other municipal authorities. The provision of better infrastructure would mean that the informal trader will be helped to become more able to not only sustain their businesses and their families but to also give them better opportunities to grow their business.

Communication

One of the major barriers faced by participants in the informal economy was lack of correct information about processes to be followed or to give advice. The municipality was not communicating well with the street traders such that they resorted depending on the grapevine which obviously cannot be a reliable source. This gap was found in this study where most of the respondents said they did not know anything about the informal economy policy and those who knew about it only heard it from their fellow traders. It is recommended that the municipality should involve the street traders in their decision making. It should strive by all means to involve their leaders when coming up with legislation, location of stalls and other major decisions that affect them.

Recommendations to the Informal Traders

It is important that traders take action to deal with some of the problems. The government can make provision for these businesses and make facilities available but there is bound to be a limit to how much it can do so it is up to the end user to utilise them, in this case that means the participants in the informal economy. What follows below are some suggestions whichmight be helpful to convey to participants in the informal sector. It is therefore recommended that the informal traders should be given the following advice:

- Be familiar with and follow the bylaws of the municipality;

- Study and understand all the relevant informal economy policies;

- Register their businesses;

- Attend relevant meetings and workshops that are called by the municipality;

- Develop their business management, marketing, finance and other skills related to their form of business; It may be possible for them to obtain formal qualifications in some cases from private and public sector institutions;

- Pool their resources together and buy in bulk and diversify the products they have for sale;

- Monitor and check what is being traded by others to avoid duplication and dysfunctional competition where possible;

- Improve operations and service delivery;

- Endeavour to grow their businesses from survival mode to sustainability;

- Follow proper channels to air their grievances, which can be through their business related leaders and local ward and other councillors.

- Take advantage of any financial assistance that may be made available.

Policy Recommendations

National Development Plan

The NDP supposedly laid the foundation for the development trajectory of South Africa up to 2030 and beyond. It calls for action in a number of areas which are highlighted in this section as priorities. However, as with much planning in South Africa and elsewhere, implementation is a serious challenge to the capacity of the municipality.

The plan first of all highlights the major challenges that the economy of the country is facing. It noted some achievements that have been attained since 1994. Some of the major challenges pointed out were inequality, poverty and high unemployment levels. In order to address this, it proffers a solution of inclusive growth. Small enterprises are identified as one source of growth for the economy. It noted that the regulatory environment needs to be reviewed in order to reduce red tape (unnecessary and slow bureaucratic processes). Despite this being pointed out, there remain a very high percentage of unregistered (small micro and medium enterprises (SMME) as pointed out in this study. The challenges that were pointed out that are faced by SMMEs still exist up to the time when the study was carried out. These challenges include lack of skills, lack of finance and too many regulations.

The eThekwini IDP: Recommendations

Informal economy issues are covered in the plan 2 part of the IDP which highlights that “street trading is a demanding task involving demarcation of trading areas, issuing of permits, organising traders into area committees that feed into a citywide forum, and on-going collection of rentals” (EM, 2018). It points to the complexity of the management of street vending in the municipality and directs most of the management to the Durban’s Informal Policy. However, the IDP is meant to direct the operations, budgeting and prioritisation of the municipality for a certain period to achieve certain goals whilst being guided by the municipal, provincial and national policies and strategies. The IDP should have laid out a more workable plan on how street trading is going to be managed, which is a priority need emerging from the research.

This article has shown that there is an information gap between the municipality and the informal traders. The informal traders are not well informed about the policies and strategies of the municipalities. This was highlighted earlier on, when street traders embarked on demonstrations opposing new bylaws.

The IDP lists one of the key performance indicators as “Managing the Informal Economy by providing an enabling platform for the local informal sector by implementing a set of operational and management initiatives as outlined in the Service Delivery Budget. Implementation Plan” (EM 2019). The five-year target to be achieved by 2022 is to have “a competitive informal economy with improved product quality and bigger market” (EM 2019). It is not clear how the informal economy competitiveness is going to be measured. Therefore the target can be said to be vague and needing to be clarified.

Although the IDP has made some positive strides towards managing and catering for the informal traders, there is still room for incorporating the concerns raised by the informal traders themselves as reflected, for example, in this study.

Conclusion

This study has revealed in some detail the challenges facing informal traders in eThekwini. The findings have established that informal traders face many challenges which include inter alia the shortage of finance, lack of storage space and lack of awareness of the informal economy policy. The above mentioned challenges lead to inadequate business operations which ultimately can lead to the business being unable to grow and to maintain its sustainability. A number of recommendations have been made. Informal traders should be educated to become aware of informal polices to ensure that their business activities are managed appropriately. To support growth and the acquisition of knowledge, professionally delivered business management training will also enable informal traders to obtain skills that will empower them to improve their decision-making.

Finally, municipal authorities as well as other key players in other spheres of government and elsewhere, including policy makers, should take note that if the informal trader is successful as a result of an improved policy impact, then poverty in its various manifestations will decrease as individuals will then not only create their own employment but ultimately enable employment opportunities for others if and when the business grows.

Acknowledgement

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical consideration

This article followed all ethical standards for carrying out the research.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

References

- Beavon, K.S.O. (1989). Informal Ways: A window on informal business in South Africa. Small Business Development Corporation. Pretoria.

- BusinessTech (2020). Major new laws planned for small businesses in South Africa. Retrieved from https://businesstech.co.za/news/business/456514/major-new-laws-planned-for-small-businesses-in-south-africa/ [Accessed online on 23 December 2020].

- DTI (Department of Trade and Industry. (2014). National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy (NIBUS). Pretoria.

- EM (eThekwini Municipality) (2018). Integrated Development Plan (IDP) 5 Year plan. 2018/2019 Review. Durban.

- EM (eThekwini Municipality) (2019). Introduction to the history of Durban [online]. Available at http://www.durban.gov.za. (Accessed 6 October 2020).

- Fredström, A., Peltonen, J., & Wincent, J. (2020). A country-level institutional perspective on entrepreneurship productivity: The effects of informal economy and regulation. Journal of Business Venturing, 106002.

- Fundie, A.M.S., Chisoro, C. and Karodia, A.M., (2015). The Challenges Facing Informal Traders in the Hilbrow Area of Johannesburg. Kuwait Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 33(2581):1-30.

- Lund, F., (2014). Street trading. Durban School of Development Studies. University of KwaZulu-Natal, 114-123.

- Portes, A., Castells, M. and Benton, L.A. (1989). ‘Conclusion: The Policy Implications of Informality’ in A. Portes et al. (eds) The Informal Economy, 296-310. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Nel, E.L. (1999). Regional and local economic development in South Africa: The experience of the Eastern Cape. Ashgate Publishing.

- RSA (2000). Local Government: Municipal Systems Act 32 of 2000. Pretoria

- Saunders, M, Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2019). Research Methods for Business Students. 7th Edition Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited.

- Stats SA (Statistics South Africa) (2016). 2nd quarter 2016. Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS). Pretoria.

- Sutherland, C., Scott, D. and Hordijk, M., 2015. Urban water governance for more inclusive development: A reflection on the ‘waterscapes’ of Durban, South Africa. The European Journal of Development Research, 27(4): 488-504.

- Valodia, I., Lebani, L.,Skinner, C., and Devey, R.(2006). Low-waged and Informal Employment in South Africa. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa. 60: 90-126.

- Welman, J.C., Kruger, S. & Mitchell, B. (2005). Research Methodology. 3rd Edition, Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.