Research Article: 2023 Vol: 27 Issue: 4

Assessment of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Performance in Southwest Nigeria

Oke, Dorcas Funmilola, Federal University of Technology

Citation Information: Dorcas Funmilola. O., (2023). Assessment Of Micro, Small And Medium Enterprises Performance In Southwest Nigeria, International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 27(S4),1-19

Keywords

MSMES, Performance, Profitability, Covid-19, Finance.

Introduction

There is an increasing recognition among economists that economic growth driven by private enterprise offers a better promise for poverty reduction by reducing the levels of unemployment and strengthening individuals’ ability to care for themselves and their families, while generating income necessary for anti-poverty policies of governments (Nafukho & Muyia, 2010). Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) play a vital role in economic transformation and industrialisation both for developed and developing countries. MSMEs are the channel to meet and achieve most of the economic-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth, increasing employment opportunities, especially for the poor, eradicating poverty, advancing sustainable industrialisation, and innovation and creating a positive higher quality of life for all (United Nation, 2019). Nations, regions and communities that actively promote enterprise development exhibit much higher levels of development than the nations whose institutions, policies and cultures hinder enterprises (Landes, 1998). A survey of Investment Climate in Nigeria (ICN, 2016) revealed that more than seventy per cent (70%) of Nigeria’s labour force are self-employed and the private sector contributes significantly to the Nigerian economy and accounts for 50% of the GDP (National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), 2017). Enterprise growth has been recognised in the literature as a developing stage from stagnancy to growth either in assets, productivity or employees (Reeg, 2013). (Faltejskova, Dvorakova, Hotovcova, 2016) stated that enterprise growth and performance can be an indicator in measuring the success, ability to compete, and a chance to ensure the sustainability of a business in a specific industry. According to (Mbiti et al., 2015), growth is the heart of any business which makes the relationship between growth and enterprise a relevant question. However, growth means increase in sales turnover, increase in profitability, increase in the number of employees, production lines, services and total capitalisation. It involves the degree to which business owner manage to achieve its purpose and goals (Mulyono, 2013).

MSMEs performance is a function of several factors - international, national, industry, or from firm itself (Beck & Demirguc-Kunt, 2006). Among the various factors affecting MSMEs' performance, the educational level of business owners, gender, and financial literacy are major influences (Woldie, Leighton & Adesua, 2008). Business performance can be evaluated and measured from two perspectives; financial or objective and non-financial or subjective measurement (Kaplan & Norton, 1992; Laukkanen et al., 2013). The objective performance measure of business which is also referred to as financial performance is the accounting-based measure of MSMEs performance. Financial performance can be described in terms of business growth, which is gauged by changes in the number of employees, sales, assets, profitability, revenue, return on equity (ROE), and earnings per share (EPS) (Chong, 2008; Rauch et al., 2009; Santos & Brito, 2012; Laukkanen et al., 2013; Gerba & Viswanadham, 2016). Subjective measures or non-financial or operational measures of performance on the other hand include employee growth; market share; customers’ satisfaction and retention rate; customers’ referral rates; employees’ satisfaction; product quality; and introduction of new product/innovation; (Chong, 2008; Richard et al., 2009; Santos & Brito, 2012).

MSMEs in Nigeria are confronted with a myriad of challenges, such as poor external business environment, poor infrastructure facilities, and poor access to finance (Smedan, 2017). (Olowe, Moradeyo & Babalola 2013 & Gololo, 2017) observed that most MSMEs in Southwest Nigeria were not able to attain their growth stage due to inadequate access to finance, low level of income, poor infrastructural facilities, and unstable government policies. The performance of MSMEs in Nigeria, especially in the Southwest, has been hampered by an unstable political, economic, and social business environment, lack of access to finance particularly from formal financial institution, corruption, poor managerial skills and insecurity among others (Ayedun, Asikhia & Oduyoye, 2015, Oke, Soetan & Ayedun, 2023). The majority of MSMEs in Nigeria fail within a few years of operation. Most of these failures could be avoided if these MSMEs had strategies in place to track and evaluate their performance (Chingwaru, 2016; Gerba & Viswanadham, 2016). As a result, a study to delve into and assess the performance of MSMEs is necessary. While previous research has focused on identifying the causes of MSMEs' failure (Kambwale, Chisoro, & Karodia, 2015; Abubakar, 2019; Bushe, 2019), this study aims not only to assess MSMEs' performance but also to identify challenges faced and the key coping strategies to overcome these challenges.

Literature Review

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework for this study was Resource-Based Theory (RBT). RBT was developed in the 1980s and 1990s, following the important works by (Wernerfelt, 1984), (Hamel & Prahalad, 1989), and Barney (1991). The RBT is a theory that postulates that resources are critical to firm performance (Jurevicius, 2013). RBT provides a framework to highlight and predict the fundamentals of firm performance and competitive advantage. It is a key theoretical foundation that explains MSMEs growth and performance (Asikhia, 2016). There are two fundamental assumptions that underpin RBT as related to the explanation of how firm-based resources generate sustained competitive advantage and why some firms may continually outperform others by gaining higher competitiveness (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003).

The first argument of RBT is the resource heterogeneity which assumed that firm possesses unique resources in specific ways that create competitive advantage. That is, the resources owned by firms are different from each other and thus perform and grow differently (Helfat & Peteraf, 2003). The second assumption of RBT is that resources are immobile. The resources must be imperfectly immovable, that is the valuable and scarce resources owned by a firm cannot be easily obtained by other firms. RBT aims to elaborate on imperfectly immutable firm resources that could potentially become the sources of sustained competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). Barney (1991) & Wernerfelt (1984) claimed that based on these assumptions of the resource-based viewpoint and its intra-organisational focus, performance is a product of a firm's specific resources and abilities. Resource-based theory states that business owner's financial resources are an important determinant of opportunity and new venture growth. The main concept that determines a firm’s profits potential is the firm’s internal factors, such as resources and capabilities (Porter, 1989). The firm's ability to discover and act on discovery opportunities increases with access to resources.

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises

MSMEs definition varies from country to country and from industry to industry. It can be defined using headcount (number of employees), turnover, and balance sheet assets of an organisation. MSMEs were defined in the National Policy on MSMEs using number of employees and assets (excluding land and buildings) (SMEDAN) (2017). Micro-enterprises were defined as enterprises with total assets of less than ten million naira (excluding land and buildings) and less than 10 employees. Small businesses were defined as businesses with total assets (excluding land and buildings) of more than ten million naira but less than one hundred million naira and a workforce of more than 10 but less than 49 employees. Medium businesses have total assets (excluding land and buildings) of more than fifty million naira but less than one billion naira and a workforce of between 50 and 199 employees as can be seen in Table 1 (SMEDAN, 2017).

| Table 1 Classification of Enterprises In Nigeria | |||

| S/N | Size Category | Headcount (Employees) | Assets (Million naira) |

| 1 | Micro Enterprises | Less than 10 (1-9) | Less than 10 |

| 2 | Small Enterprises | Between 10 to 49 (10-49) | 10 to less than 100(10 – 199) |

| 3 | Medium Enterprises | 50 -199 | 100 to less than 1,000 |

| Source: SMEDAN National Policy on MSMEs, (2017) | |||

Bank of Industry (2020) defined MSMEs as; Micro enterprises as enterprises with less than or equal to 10 employees, total assets less than or equal to ₦5million, annual turnover of less than or equal ₦20million with loan amounts less than or equal to ₦10million. Small enterprises were enterprises greater than 11 and less than or equal to 50 employees with total assets of greater than ₦5million or less than or equal to ₦100million, annual turnover of less than or equal to ₦100million with a total loan amount greater than ₦10million or less than or equal to ₦100million. While Medium enterprises were enterprises with greater than 51 and less than or equal to 200 employees with total assets of greater than ₦100 and less than or equal to ₦500million and loan amounts greater than ₦100million and less than or equal to ₦500million.

Business Performance

Business performance involves the extent to which a business owner achieves its purposes and goals (Mulyono, 2013). Growth, survival, success, and competitiveness are all terms that are used to describe performance (Gerba & Viswanadham, 2016). Performance can be defined as a firm's ability to generate desirable outcomes and actions (Chittithaworn, Slam, Keawchana & Yusuf, 2011; Eniola & Entebang, 2015). Performance can also be defined as an organisation’s ability to take advantage of its environment to gain access to and utilise limited resources (Yuchtman & Seashore, 1967). (Robbins, 1987) defined performance as an organisation’s capacity to consider both its means and ends as a social system. Cherrington (1989) considered performance as a concept of an organisation’s success or effectiveness, as well as an indication of how well an organisation is performing to achieve its objectives.

Business performance is a concept that has different meanings and definitions (Lebans & Euske, 2006; Gerba & Viswanadham, 2016). Business performance, according to Lebans & Euske (2006), can be defined as "doing today what will result in a measured value outcome tomorrow." A measure of a company's effectiveness and efficiency is called business performance (Neely et al., 2002; Lebans & Euske, 2006; Michaela & Marketa, 2012). Effectiveness refers to how well a company meets its investors' expectations, while efficiency refers to how well a company uses its resources to meet those needs (Neely et al., 2002). Business performance can be measured using financial and non-financial measurement (Kaplan & Norton, 1992; Laukkanen et al., 2013). Financial performance is the accounting-based measure of MSMEs performance while non-financial measures of performance use employee growth; market share; customers’ satisfaction and retention rate; customers’ referral rates; and employees’ satisfaction as a measure of business performance (Chong, 2008; Richard et al., 2009; Santos & Brito, 2012). A meta-analysis by (Levie & Autio, 2013) showed that enterprise growth has been widely measured using asset growth, sales growth and employee growth. Financial indicators are expected to reflect the fulfilment of the economic aims of the organisation (Hofer, 1983). Financial measures have the advantage of being objective, simple and easy to understand. However, they are not easily available and can be subject to manipulation, and incompleteness (Chong, 2008; Santos & Brito, 2012). The non-financial measures are widely used for self-reported performance but they are considered as being subjective (Santos & Brito, 2012).

The use of subjective measurements for business performance is made more necessary by the relative difficulty, particularly for micro and small business, of gathering objective financial data and their penchant for poor record keeping in developing countries (Dess & Robinson, 1984). However, there is a lack of consensus among researchers about the most appropriate measures of performance. Studies suggested that no one measure of performance could be used to get a comprehensive measure of how business perform and also owing to the limitation of both measures (financial or objective and non-financial or subjective), both should be used together (Watson, 2007 & Fowowe, 2017). For instance, (Hax & Majluf, 1984) have emphasised that market or value-based measurements are more suitable than accounting-based measures such as stock-market returns for assessing performance. Also, (Rauch et al., 2009) considered satisfaction to be the basic measure of enterprise performance. Financial measures are commonly used by most studies (Murphy, Trailer & Hill, 1996). However, lack of financial records among MSMEs in Nigeria makes it impossible to adopt financial performance measurement but rather their performance could be measured using subjective or non-financial or operational measurements (Asikhia, 2016).

Empirical Review

Examining the nexus between access to credit and the growth of SMEs in the Ho-Municipality of Ghana, Ahiawodzi & Adade (2012), showed that access to credit had a significant positive effect on SMEs' growth in the Ho-Municipality of Ghana. That is, using the employment level of the business as a proxy for growth, the results of the multiple regression analysis revealed that access to credit, increase in total current investment, start-up capital, and annual turnover had a significant positive effect on the growth of SMEs in the manufacturing sector. Ogbuabor, Malaolu, and Elias (2013) examined the historical trend in the development of SMEs in Nigeria and observed that despite the contributions of SMEs and their importance in job creation, SMEs has always faced difficulty in obtaining formal credit or equity from financial markets which in turn inhibit their performance. On the other hand, (Mashenene & Rumanyika 2014) found that the owner’s capital, credit availability, and the age of the owners did not affect SME’s performance in Tanzania, but the management ability of business owners, level of education, ethnicity and motivation of business owners had a significant positive effect on SME performance.

(Abera, Ali, & Girma, 2019) used micro and small-scale manufacturing enterprises in selected towns of Jimma zone as a case study to analyse the firm growth determinants using binary logistic regression. The result reveals that the initial investment capital, operator experience, access to credit, training for the firm operators have a significant positive effect on firm’s growth. (Weldeslassie, et al, & Gidey, 2019) used Ethiopia as a case study to investigate the contributions of MSMEs to income generation, employment, and GDP. Lack of credit, poor market linkage, insufficient training, weak human resource development schemes, reliance on government, fluctuations in government policies, price variations, and poor market and product development strategies were the main obstacles to SMEs' development in the study area. Similarly, (Eton, Mwosi, Okello-Obura, Turyhebwa, & Uwonda, 2021) used a cross-sectional research design, correlation analysis, and regression analysis to examine the effects of access to finance on the expansion of SMEs in Uganda. The study found that access to finance significantly impacted the expansion of SMEs. The study also demonstrated the high costs associated with obtaining and maintaining financial services are the most challenging associated with using some financial services in Uganda.

Methodology

Sequential Explanatory Mixed (SEM) research design was employed with the use of a structured questionnaire, and an in-depth interview. A mixed-methods approach is triangulation methodology for conducting research that involves collecting, analysing data and integrating quantitative (e,g questionnaire, experiment) and qualitative (e,g observation, in-depth interview, Focus group discussions) research. Sequential Explanatory Mixed (SEM) research design is useful for research involving a non-observable event such as opinions, attitudes preferences and personalities (Ryan et al., 2002). The justification for this research method is because the mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods offers a better understanding of research problems than either method alone.

The quantitative data were obtained with a structured questionnaire and were administered to the business owners in the study areas. The study population consists of MSMEs in Southwest Nigeria. In Southwest Nigeria, there were nine million eight hundred and eighty-six thousand, five hundred and thirty-eight (9,886,538) MSMEs (SMEDAN, 2017) as presented in Table 2. Out of these, Lagos and Ondo States had a total of four million three hundred and ninety-seven thousand, nine hundred and forty-five (4,397,945) MSMEs, constituting 44.5% of the total MSMEs in Southwest Nigeria.

| Table 2 Msmes in Southwest Nigeria | ||||

| State | MSME's | Micro | Small | Medium |

| Ekiti | 10,17,510 | 926 | 2 | 10,18,438 |

| Lagos | 33,29,156 | 8,042 | 354 | 11,80,574 |

| Ogun | 11,78,109 | 2,394 | 71 | 33,37,552 |

| Ondo | 10,58,025 | 2,329 | 39 | 10,60,393 |

| Osun | 13,70,908 | 2,995 | 12 | 13,73,915 |

| Oyo | 19,09,475 | 6,039 | 92 | 19,15,606 |

| TOTAL | 98,63,183 | 22,725 | 570 | 98,86,478 |

| Source: Smedan’s Report, (2017) | ||||

The sample size for this study was based on the total population of enterprises in the two selected states in Southwest Nigeria (Lagos State have 3,337,552 MSMEs and Ondo State have 1,060,393 MSMEs) totalling 4,397,945 MSMEs. The sample size was calculated using (Taro Yamane, 1967) formula and adopted by (Haftom, Fisseha, Araya, 2014). The total sample for the study was 440. The selection of the sample size was achieved through a multi-stage sampling technique that involves purposive sampling and simple random sampling techniques. Two states were purposively selected in Southwest Nigeria. Each state capital of these two states was purposively selected for survey location being the commercial centre of the state. Businesses were grouped into four sectors. These four sectors are Manufacturing/production sector (this comprises of block making, sachet and bottled water firms, bakeries, and the garment industries); Wholesale and Retail trade sector (includes supermarket stores and retail outlets); Agricultural sector (poultry businesses and other related enterprises in agriculture); and Service sector (comprises of hospitality businesses, food services, education and filling stations).

Similarly, in-depth interviews were conducted to complement the findings of the questionnaire. Purposive sampling techniques were used to select eight business owners for in-depth interviews in the trading, services, manufacturing and agricultural sectors across the two states.

The study employs descriptive statistics to analyse the data collected from the respondents. Descriptive statistics including frequency distribution, mean, charts, tables and percentages. Spearman test and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were also conducted to establish relationship and compare the mean difference among the variables. For qualitative data which is the in-depth interviews, inductive coding method was used. This is an open coding method in which the coding was created entirely from scratch using the qualitative data alone, without the aid of a codebook. In other words, all codes are derived directly from survey responses. Responses were coded into thematic areas and content analysis was used to analyse the results. Additionally, network diagrams were made using the ATLAS.ti software for simple data visualization.

Analysis and Discussion of Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

This section explores the characteristics of respondents in the study areas. Table 3 presents the profile of MSMEs in Southwest Nigeria. Four Hundred and Forty (440) questionnaires were distributed out of which 409 were retrieved (93%) from study states

| Table 3 Average Monthly Profit | |||||

| At the Peak Period of Sales (In Thousand naira) | |||||

| Less than ₦100 | Between ₦100 - ₦300 | Between ₦300-₦500 | Between ₦500-₦1m | Total | |

| Micro Enterprises | 120 (42.1%) | 87 (30.5%) | 62 (21.8%) | 16 (5.6%) | 285 |

| Small Enterprises | 11 (9.3%) | 47 (39.8%) | 34 (28.8%) | 26 (22.0%) | 118 |

| Medium Enterprises | 0 | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 3(50.0 %) | 6 |

| Total | 131 (32.0%) | 135 (33.0%) | 98 (24.0%) | 45(11.0%) | 409 |

| At the Low Period of Sales (In Thousand naira) | |||||

| Less than ₦100 | Between ₦100 - ₦300 | Between ₦300-₦500 | Between ₦500-₦1m | Total | |

| Micro Enterprises | 188 (66.0%) | 1 (24.9%) | 23 (8.1%) | 3 (1.1%) | 285 |

| Small Enterprises | 42 (35.6%) | 44 (37.6%) | 24 (20.3%) | 8 (6.8%) | 118 |

| Medium Enterprises | 0 | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 230 (56.2%) | 117(28.6%) | 51 (12.5%) | 11 (2.7%) | 409 |

| Source: Author’s computation (2022) | |||||

Figure 1 shows that the survey respondents were made up of mostly females 208 (50.9%) and male respondents of 201(49.1%).

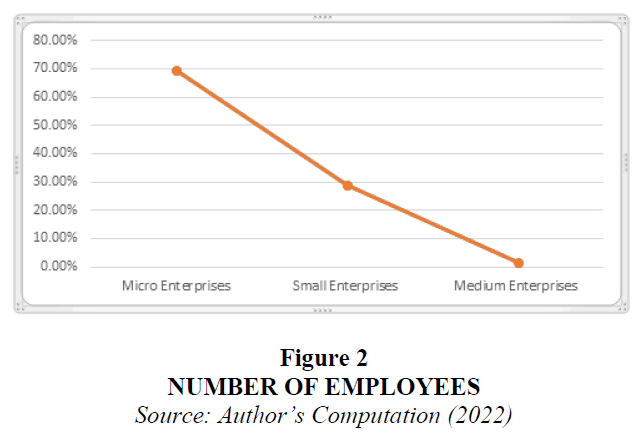

For sample employees as depicted in Figure 2, micro-enterprises which had between 1-9 employees had the largest percentage (69.7%) of the total sample; followed by small enterprises (between 10-50 employees) with a sample size of 28.8%; while medium enterprises (between 51-200 employees) had the least percentage (1.5%). The implication of this is that majority of the businesses operating in the study area are micro-enterprises which corroborates the finding of (Smedan 2017 & Nbs 2017) that micro-enterprises constituted about 99.8% of total MSMEs in Nigeria; small enterprises constitute 0.17% and medium enterprises 0.004%.

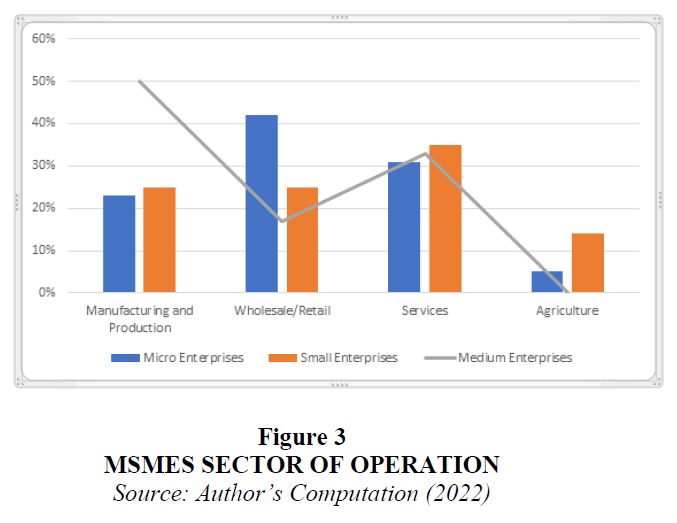

The study focused on four main sectors namely manufacturing and production, wholesale/retail, services and agriculture. Most of the micro-enterprises that responded to the questionnaire were in the wholesale/retail sector as can be seen in Figure 3. Approximately, forty-two per cent of the respondents were into wholesale/retail, thirty-one per cent into the services sector, twenty-three and five per cent were into manufacturing and agricultural sectors respectively. This may be because micro-enterprises dealing in wholesale/retail. There was also a high response rate from small enterprises in the service sector as showed by a (35%) well above those for manufacturing/production, wholesale/retail and agricultural sectors (25%, 25%, and 14%) in the study area. 50% of the medium enterprises were into manufacturing/production, followed by the service sector (33%). This implies that different sectors function differently in different enterprises probably because of the capital requirements for those sectors. Micro-enterprises in the wholesale/retail sector had the highest percentage; small enterprises in the services sector had the major ratio while the manufacturing/production sector had the highest percentage for medium enterprises. MSMEs responses to the questionnaire based on their sector of operation are as shown in Figure 3.

Constraints to MSMES Performance

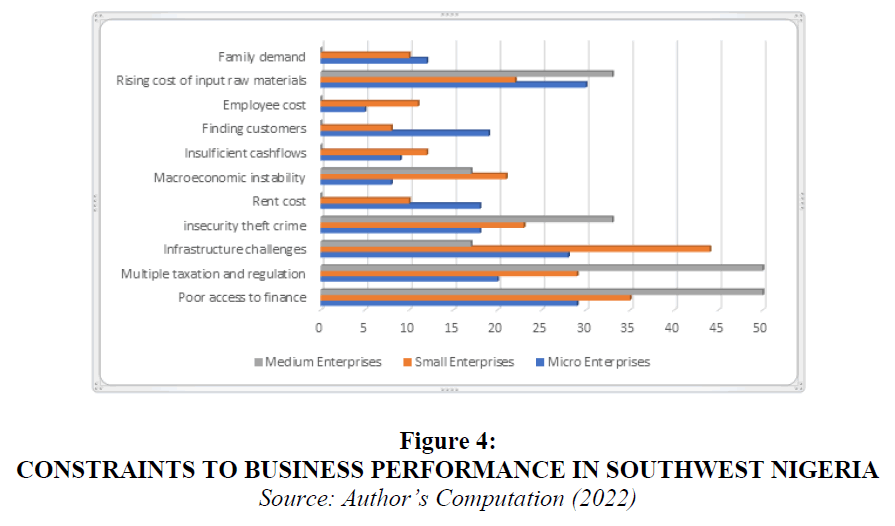

MSMEs respondents indicated that factors alongside insufficient business funding negatively influences their performance. Specifically, the majority of respondents claimed that limited access to finance, interrupted electricity power supply, poor road networks, high cost of materials/increase in the prices of raw materials, insecurity and multiple taxation charges are the major obstacles to the successful operation of their business. For instance, approximately half of the medium enterprises’ operators, 35% and 29% of the small and micro enterprises respondents, respectively, indicated that poor access to finance was the main challenge that hindered their business performance and growth as shown in Figure 4. Poor access to capital was a primary impediment to MSMEs’ performance while one of the most consistent themes from MSME owners’ interviews was that lack of loan capital was a major obstacle to the growth and expansion of their businesses. Generally, MSME owners believe that additional capital alone will solve the majority, if not all, of the problems they faced. (Fowowe, 2017) finding corroborates the finding in this study as he revealed that constraint in access to finance has a significant negative effect on firm growth.

Figure 4 Constraints to Business Performance in Southwest Nigeria

Source: Author’s Computation (2022)

Similarly, multiple taxation and regulation were also indicated as one of the key hindrances to MSMEs' performance. Virtually 50%, 29% and 20% of medium, small and micro business owners reported that their businesses had been hampered by paying multiple taxations to the government at the various levels. Most respondents reported that the country’s economic instability at the time, coupled with a high inflation rate, resulted in the general increase in the prices of goods and materials for production or retail. On averagely, 30% of the MSMEs owners indicated that unstable and high prices of goods and raw materials affected their business performance.

Many MSMEs respondents revealed that poor infrastructure affected their business performance. Regardless of the amount of credit or equity funding offered to the sector from commercial banks, epileptic supply of electricity and poor road networks will continue to hamper the growth and expansion of the MSMEs sector in Nigeria. Nigeria now ranks 131 on the World Bank's Doing Business 2020 index. The country moved 15 places up from its 2019 position and was therefore declared as one of the most improved economies in the world. Despite this improvement, more work has to be done to improve business environment and remove structural barriers to performance for the MSME sector in the country. The findings of this study align with the findings of (Olowe et al., 2013 & Gololo, 2017) which established that most MSMEs in Southwest Nigeria were not able to attain their growth stage due to inadequate access to finance, low level of income, and poor infrastructural facilities.

Similar responses were identified by MSME owner’s in-depth interview conducted on the constraints to MSMEs performance, as revealed in excerpts in Box 1. Majority of the MSME owners interviewed indicated paucity of funds to finance their businesses was the major constraints to business performance. This response is consistent for MSME owners in both Lagos and Ondo State. Respondents also reported that general increase in the prices of goods and materials used in the production of goods, coupled with the decline in the quality of goods and insufficient supply of goods in the market, negatively affected the performance of business. Respondents further reported that customers’ complaint about the rise in the prices of goods and low-quality of their products, together with economic meltdown in the country, resulted in low sales and a reduction in their profit. Poor infrastructural facilities were also identified as one of the major constraints to the business performance. Respondents indicated that poor power supply resulted into the use of generators to run their businesses.

In-depth interviews on Constraints to MSMEs Performance

“Scarcity of goods in the last three years has been a major constraint. Although goods used to be available before, it is now difficult to get them supplied to us. Equally, while the quality of goods is reducing, the price is increasing everyday. These are the major factors affecting business performance.” – [A female provision seller with ten employees and seven years in business].

“The increase in the price of goods/products, coupled with the low quality of goods/products, is the major challenge I am facing now […] -- [A female with three employees.].

“There is no help coming from anywhere in spite of the high cost of things in the country now. So, the main challenge is finance and I am not buoyant enough to finance my business for it to perform as I wish.” – [A female fashion designer]

“Inadequate finance is the major challenge to my desired business performance.”— [A 33-year-old male block moulders with ten years in business. Currently has ten employees from the previous six].

“…paucity of funds to finance the school is a major problem. So, I’ll say poor access to finance is our major challenge as a business owner.”— [A male Nursery and Primary School Proprietor in Ondo State with ten employees and six years in business].

“The major constraints are weather and increase in the price of cement and sand day by day. I sell more during dry season; most people build houses during dry season. There is a reduction in sales of blocks during raining season”. [A male block moulder in Lagos State with 5 workers]

Source: Field work (2022)

Invariably, the cost of buying fuel to run their generators increased their overhead cost and led to profit reduction.

Key Factors Helping Business Performance and Coping Strategies for MSMEs' Performance

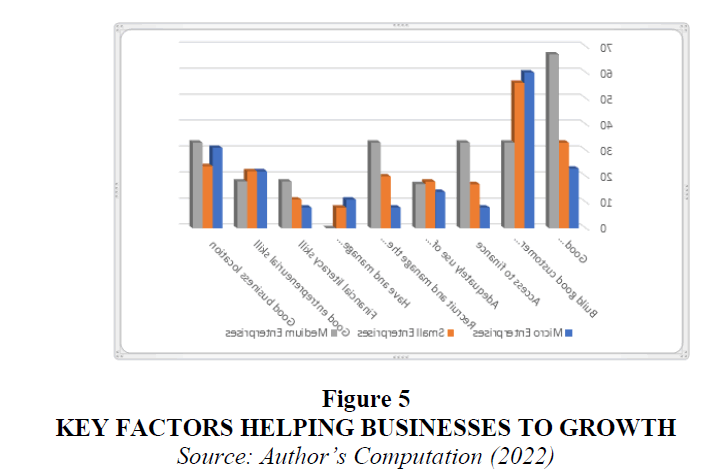

One of the key factors that enhanced the performance and the growth of the MSMEs especially the micro and small businesses are building good customer’s relationship. More than half (60% and 56%) of micro and small business owners reported that having and building good customers relationship is one of the secrets to the growth of their businesses and the most effective coping strategy to overcome the challenges facing their business performance. Figure 5 reveals that good leadership and managerial quality were crucial to the performance of medium enterprises in the study area. Good business location was also reported by the MSME owners as one of the key factors that help their business growth and performance. Thirty-three per cent of medium enterprises owners; thirty-one per cent of micro enterprises; and twenty-four per cent of small enterprises indicated that their businesses progressed due to their business locations. Good entrepreneurial skills also assisted MSMEs owners to perform well.

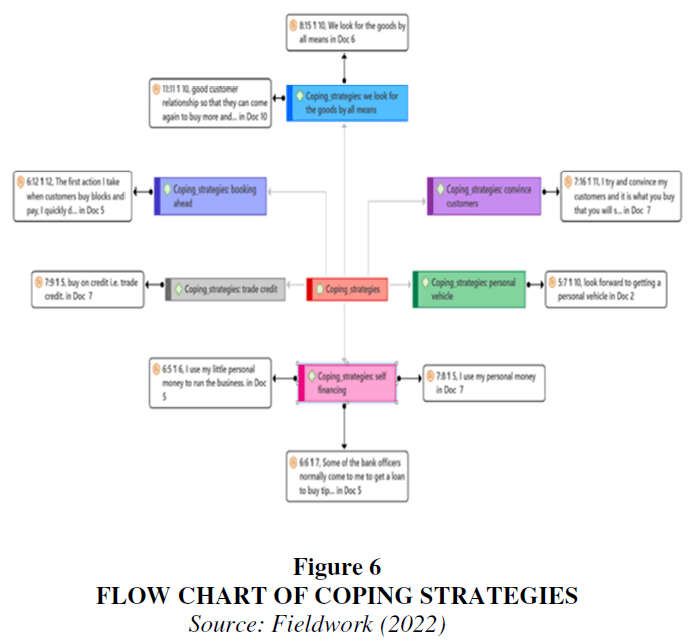

Respondents revealed an array of coping strategies in relation to each of the challenges they had reported. For instance, some of the respondents reported that they had operated other businesses like farming, bags/shoe production to cope with insufficient finance, low sales and reduced profit. Others improved on their good customer relations which helped customers to understand the reasons for price increase. This way, improved customer relations helped to sustain the continued patronage of the customers to ensure increased sales and income. Lastly, some persuaded and tried to convince their customers to transact business with them. Figure 6 presents the flowchart (using ATLAS.ti software) of some of the identified coping strategies adopted by MSMEs owners to overcome the constraints that inhibit their business performance.

MSMEs Performance Measured on Profitability Level

Profit level is widely used to evaluate the financial success of businesses (Blackburn et al., 2013). The profitability level of the MSMEs both at the peak period and the low periods of sales as reported by the owners of the enterprises in the Southwest was used. Table 3 shows that majority of the micro-enterprises that responded to the questionnaires reported an average of less than ₦100,00 monthly profit (42.1%) at the peak period of sales. Only 30.5% of the micro enterprises’ respondents indicated that they made a monthly profit of between ₦100,000-₦300,000, and just 5.6% made a monthly profit of between ₦500,000- ₦1m at the peak period of sales. At the low period of sales, more than half (66%) of the micro enterprises’ operators reported that they made a monthly profit of less than ₦100,000 (Table 3).

For small enterprises, 40% responded that they made a monthly profit between ₦100,000-₦300,000; 29% made a monthly profit between ₦300,000-₦500,000; 22% made a monthly profit of between ₦500,000-₦1m; and just 9.3% had less than ₦100,000 monthly profit at the peak period of sales.

At the low period of the sale, the percentage of those that had less than ₦100,000 monthly profit increased to 36 per cent and those that had monthly profit between ₦100,000-₦300,000, ₦300,00-₦500,000 and between ₦500,000-₦1m reduced to 38%, 20% and 7% respectively.

For medium enterprises, 50% of them reported that they made a monthly profit of between ₦500,000-₦1m at the peak period of sales while at the low period 67% made a monthly profit of between ₦300,000-₦500,000. Finding reveals that most of the goods and services of these MSMEs were seasonal and the period at which they were determined the rate at which their products were demanded while sales volume subsequently determined their profit level. Another important implication of these findings is that most micro-enterprises owners made a low profit of less than ₦100,000 both at the peak period and at the low period of sales. This explains their low-income level compared to small and medium enterprises.

Profit Level and Sector of Operation

The Kruskal-Wallis H test was performed to evaluate the likely differences between the profit level and sector of operation. Kruskal-Wallis H test allows one to compare the scores on some continuous variable for three or more groups. The Kruskal–Wallis H test indicated that there is a statistically significant difference in profit level both at the peak and the low sales periods across the four sectors of operation at 5% significance level (H (3) = 9.581, p = 0.022). This implies that there is a significant difference in the level of profit and sectors of operation. The manufacturing and production sector had the highest mean rank of 222.28, followed by 215.78, 213.14 and 180.29 for agriculture, wholesale/retail and service sector respectively.

Profit level and Number of Employees

Spearman correlation and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were performed to establish if there is a correlation between the level of profit and the number of employees and also if there is the existence of possible differences between the level of profit and number of employees in the MSMEs. Table 4 below displays the outcomes of the correlation and Kruskal-Wallis H tests. Spearman tests revealed a positive relationship between the level of profit and the number of employees and the result is statistically significant. The results corroborate the finding of (Perenyi & Yukhanaev, 2016) that found a positive relationship between the size of firm and profitability level.

| Table 4 Test on the Relationship Between Profit Level and Employees’ Number | ||

| Test | Coefficient | Significance Level (p value) |

| Spearman Test | 0.355 | 0 |

| Kruskal-Wallis H tests | 52.229 | 0 |

| Source: Author’s computation (2022) | ||

Likewise, Kruskal–Wallis H test shows that there is a statistically significant difference in the profit level and the number of employees at 5% significance level (H (2) = 52.229, p = 0.000). This implies that there is a significant difference in the level of profit and number of employees. This result suggests that both the level of profit and the number of employees may be appropriate measures of the MSMEs performance as the two were found to be positively related in this study.

MSMEs Performance Measured by Employees’ Growth

We measure MSMEs' performance in terms of employee growth by looking at the mean difference between two periods. Following (Fowowe, 2017), firm performance is computed as the mean difference between the current number of employees and the number of employees at the commencement of the business. The micro-enterprises employees’ growth ranges between -5 and 8, with the lowest rate at -5 and the highest rate were at 8. For small enterprises, the growth rate ranges between -7 and 40, with the lowest rate at -7 and the highest rate was at 40. The finding reveals that some MSMEs experience positive employee growth, that is, they hire more employees to meet up with their business expansion, while some experience a decrease in the number of employees or negative growth. Table 5 depicts the summary statistics of the employees’ growth; the average employee growth of MSMEs at the commencement of their business was 3.78 while it was 9.51 for current employees. The mean value for the number of employees for micro enterprises at the start was 1.96 and the mean for the current number of employees increased to 4.19 which imply an increase in the number of employees employed by the micro enterprises.

| Table 5 MSMES Performance Measured by Employees’ Growth | ||||||||

| Employees at Start | Current Employees | |||||||

| Mean | Std | Min | Max | Mean | Std | Min | Max | |

| Micro Enterprises | 1.96 | 1.18 | 0 | 15 | 4.19 | 2.65 | 0 | 9 |

| Small Enterprises | 7.39 | 5.08 | 1 | 30 | 21.33 | 11.32 | 10 | 50 |

| Medium Enterprises | 18.5 | 6.86 | 11 | 30 | 52.17 | 52.17 | 51 | 54 |

| Source: Author’s Computation, (2022) | ||||||||

The mean number of employees at the start for small enterprises was 7.39 while the current mean was 21.33. For medium enterprises, the mean at the start of the business was 18.5 and the current mean for the number of employees was 52.17. This indicated that averagely, all the enterprises experienced growth in the number of their employees.

Similarly, the statements of the respondents from the in-depth interviews conducted confirmed that almost all the MSMEs operator respondents’ experience growth in the performance of their businesses in the last three years. However, some respondents revealed that their businesses were not performing satisfactorily due to the shocks from the global COVID-19 pandemic, scarcity of goods, economic recession, and other issues. COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating effect on human and material resources. The pandemic spread across the globe and affected the global economic. The pandemic was responsible for the lay-off some of workers, the closure of many businesses and the increase in the cost of imported materials used in production. The foregoing impacted on the availability and quality of goods and resulted in the increase in prices of goods and the low demand of goods and services by customers. The effect of the pandemic lingered still on the growth and performance of business as reported by the MSME owners.

Conclusion

This study assessed the performance of MSMEs, identified the constraints to MSMEs performance and the key enabling factors for MSMEs performance in two selected Southwest states in Nigeria. The study revealed that the majority of respondents stated that poor access to finance, episodic power supply, poor road networks, high cost of materials/increase in the prices of raw materials, insecurity, and multiple taxation charges were the major obstacles to their successful business performance. Findings from the study showed that the key factors helping the performance and the growth of the MSMEs especially the micro and small businesses are building good customer relationships, good leadership and managerial skill, and accessible business location. From then findings, it can be concluded that the goods and services of the most MSMEs were seasonal and the period at which they were determined the rate at which their products were demanded while sales volume subsequently determined their profit level. Also, the findings reveal that most micro-enterprises owners made a low profit of less than ₦100,000 both at the peak period and at the low period of sales. This explains their low-income level compared to small and medium enterprises.

The country's financial policy agenda needs to place a high focus on MSMEs' ease of access to financing. As increased access to financing will improve MSMEs' performance. Government also should invest more on infrastructure, especially in the areas of constant power supply, good road network, and good internet connectivity. This will aid and promote business performance.

References

Abera, G., Ali, M., & Girma, H. (2019). Firm Growth and Its Determinants of Micro and Small Scale Manufacturing Enterprises in Selected Towns of Jimma Zone. Horn of African Journal of Business and Economics (HAJBE), 2(2), 397-447.

Abubakar, S., & Junaidu, A. S. (2019). External Environmental Factors and Failure of Small and Medium Enterprises in Kano Metropolis. Asian Journal of Economics and Empirical Research, 6(2), 180-185.

Ahiawodzi, A.K., & Adade, T.C. (2012). Access to Credit and Growth of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in the Ho Municipality of Ghana. British Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 6(2), 34-51.

Asikhia, O. U. (2016). SMEs’ wealth creation model of an emerging economy. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 9(17), 125-151.

Ayedun, T. A., Asikhia, O. U., & Oduyoye, O. O. (2015). Financial Commitment of commercial banks and entrepreneurial growth of small and medium enterprises in southwest Nigeria. A thesis at Babcock University, Ilishan Remo, 1-148.

Bank of Industry (2020). Harnessing Partnership, Promoting Development, Annual Report & Account.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of management, 17(1), 99-120.

Beck,T., & Demirguc-Kunt, A. (2006). Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint.Journal of Banking & finance, 30(11), 2931-2943.

Blackburn, R. A., Hart, M., & Wainwright, T. (2013). Small business performance: business, strategy and owner manager characteristics. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1), 8–2.

Bushe, B. (2019). The causes and impact of business failure among small to micro and medium enterprises in South Africa’, Africa’sPublic Service Delivery and Performance Review 7(1), a210.

Cherrington, D. J. (1989). Organizational behaviour: The management of individual and organizational performance. Allyn & Bacon.

Chingwaru, R. (2016). India helps set SMEs mentoring programme.

Chittithaworn, C., Islam, M. A., Keawchana, T. & Yusuf, D. H. M. (2011). Factors Affecting Business Success of Small & Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Thailand. Asian Social Science, 7 (5), 180-190.

Chong, H.G. (2008). Measuring performance of small-and-medium sized enterprises: the grounded theory approach. Journal of Business and Public Affairs, 2(1), 1-10.

Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R. B. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265–273.

Eniola, A. A., & Entebang, H. (2015). SME firm performance-financial innovation and challenges. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 334-342.

Eton, M., Mwosi, F., Okello-Obura, C., Turyehebwa, A., & Uwonda, G. (2021). Financial inclusion and the growth of small medium enterprises in Uganda: empirical evidence from selected districts in Lango sub-region. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(23), 2-23.

Faltejskova, O., Dvorakova, L., Hotovcova, B. (2016). Net Promoted Score Integration intoThe Enterprise Performance Measurement and Management System: Away to Performance Methods Development. E M Ekon. Management. 19, 93–107.

Fowowe, B. (2017). Access to finance and firm performance: Evidence from African countries. Review ofDevelopment Finance. 7, 6–17.

Gerba, Y. T., & Viswanadham, P. (2016). Performance measurement of small-scale enterprises: Review of theoretical and empirical literature. International Journal of Advanced Research, 2(3), 531-535.

Gololo, I. A. (2017). An Evaluation of the Role of Commercial Banks in Financing Small and Medium Scale Enterprises (SMEs): Evidence from Nigeria . Indian Journal of Finance and Banking, 1(1), 16-32.

Haftom, H. A., Fisseha, G. T., & Araya, H. G. (2014). External Factors Affecting the Growth of Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) in Ethiopia: A Case Study in Shire Indasselassie Town, Tigray. European Journal of Business and Management, 6,134-145.

Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1989). Strategic intent. Harvard Business Review, 67(3), 63- 76.

Hax, A. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Strategic management: An integrative perspective. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Helfat, E. & Peteraf, M.A. (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 997-1010.

Hofer, C. W. (1983). ROVA: A new measure for assessing organizational performance. Advances in strategic management, 2, 43-55.

Investment Climate Nigeria (2016). Investment Climate Statements Nigeria, Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs Report, U.S Department of State

Jurevicius, O. (2013). Resourced- based- view. Strategic Management Insight, 2(1), 1-21

Kambwale, J. N., Chisoro, C. C., & Karodia, A. M. (2015). Investigation into the causes of small and medium enterprise failures in Windhoek, Namibia. Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review,7(4), 80–109.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (2005). The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance. Vol. 70, pp. 71-79. US: Harvard business review.

Landes, D. (1998). The Wealth & Poverty of Nations: Why some are so rich and some so poor. New York,W.W Norton & Company

Laukkanen, T., Nagy, G., Hirvonen, S., Reijonen, H. & Pasanen, M. (2013). The effect of strategic orientations on business performance in SMEs A multigroup analysis comparing Hungary and Finland. International Marketing Review, 30(6), 510-535.

Lebans, M. & Euske, K. (2006). A conceptual and operational delineation of performance. Business Performance Measurement. Cambridge University Press.

Levie, J., & Autio, E. (2013). Growth and growth intentions: a meta-analysis of existing evidence , No1,White Papers, Enterprise Research Centre

Mashenene, R. G., & Rumanyika, R. (2014). Business constraints and potential growth of small andmedium enterprises in Tanzania: A Review. European Journal of Business and Management, 6(32), 72-80.

Mbiti, F. M., Mukulu, E., Mung’atu, J. & Kyalo, D. (2015). The influence of socio-cultural factors on growth of women-owned micro and small enterprises in Kitui County, Kenya International Journal of Business and Social Science. 6(7)

Mulyono, F. (2013). Company Resources in Resource-based View Theory. Journal of Business Administration, 9 (1), 59-78.

Murphy, G.B., Trailer, J. W., & Hill, R.C. (1996). Measuring Performance in Entrepreneurship Research. Journal of Business Research, 36, 15-23.

Nafukho, F., & Muyia, H. (2010). Entrepreneurship and socioeconomic development in Africa: A reality or myth? Journal of European industrial Training, 34(2), 96-109

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (2017). Annual Report. National Bureau of Statistics, Abuja.

Neely, A., Adams, C., & Kennerley, M. (2002). The Performance Prism: The Scorecard for Measuring and Managing Business Success. Financial Times, Prentice Hall, London.

OECD (2015). Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs. An OECD Scoreboard, 1-409

Oke, D. F., Soetan, R. O., & Ayedun, T. A. (2023). Financial Inclusion and the Performance of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Southwest Nigeria. 29th RSEP International Conference on Economics, Finance & Business, HCC. ST. MORITZ HOTEL, Barcelona, Spain. 39-50.

Olowe, F. T., Moradeyo, O. A., & Babalola, A. T. (2013). Empirical Study of the impact of Microfinance Banks on SMEs Growth in Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Economic and Management Sciences, 2(6). 116 -127.

Perenyi, A., & Yukhanaev, A. (2016). Testing relationships between firm size and perceptions of growth and profitability: An investigation into the practices of Australian ICT SMEs.Journal of Managerial Organisation, 22, 680–701.

Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G. T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial Orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761-787.

Reeg, C. (2013). Micro, small and medium enterprise upgrading in low-and middle-income countries: a literature review (No. 15/2013). Discussion Paper.

Richard, P. J., Devinney, T. M., Yip, G. S. & Johnson, G. (2009). Measuring Organizational Performance: Towards Methodological Best Practice. Journal of Management. 35, 718-804.

Robbins, S. P. (1987). Organizational Theory: Structure, Design, and Application. San Diego: Prentice-Hall

Ryan, B., Scapens, R., & Theobald, M. (2002). Research method and methodology in Finance and Accounting. 2nd Edition, London: Thomson

Santos, J. B., & Brito, L. A. L. (2012). Toward a Subjective Measurement Model for Firm Performance. Brazilian Administration Review, 9(6), 95-117.

Small Business Administration (SBA), (2009). Small Business Economy 2009: A Report to the President, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, .US

Striteska, M., & Spickova, M. (2012). Review and comparison of performance measurement systems. Journal of Organizational Management Studies, 2012, 1.

Taro Yamane, (1967). Statistics: An Introductory Analysis, 2nd Ed., New York: Harper and Row.

United Nations (2019). Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development, Financing for Sustainable Development Report, New York: United Nations.

Watson, J. (2007). Modeling the relationship between networking and firm performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(6), 852–874.

Weldeslassie, H. A., Vermaack, C., kristos, K., Minwuyelet, L., Tsegay, M., Tekola, N. H., & Gidey, Y. (2019). Contributions of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) to Income Generation, Employment and GDP: Case Study Ethiopia . Journal of Sustainable Development, 12(3), 49-81.

Wernerfert, B. (1984). A Resource Based View of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 59(2), 171-180.

Woldie, A., Leighton, P., & Adesua, A. (2008). Factors influencing small and medium enterprises (SMEs): an exploratory study of owner/manager and firm characteristics. Banks and Bank Systems, 3(3), 5-13.

Yuchtman, E., &Seashore, S. E. (1967). A System Resource Approach to Organizational Effectiveness. American Sociological Review, 32(6), 891-903

Received: 30-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-23-13508; Editor assigned: 03-Apr-2023, Pre QC No. IJE-23-13508(PQ); Reviewed: 17-Apr-2023, QC No. IJE-23-13508; Revised: 21-Apr-2023, Manuscript No. IJE-23-13508(R); Published: 23-Apr-2023