Case Reports: 2018 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

Burning Platform Consultants: American Cross-cultural Management in China

Stephanie D. Trendowski, Valparaiso University

James M. Stuck, Valparaiso University

CASE DESCRIPTION

The primary subject matter of this case is cross-cultural management of an American fast food company operating in China. A secondary issue is ethical differences among different cultures. The case has a difficulty level of three; junior level. This case is designed to be to be taught in one to one and a half hours and is expected to require one hour of outside preparation by students. Names have been changed for confidentiality.

CASE SYNOPSIS

A series of critical situations face Quicks, an American fast food restaurant chain, in China. An American country manager, newly appointed, is currently balancing several burning platform issues with local Chinese business partners. “Burning platform” is consulting slang for a critical incident where the platform such as an offshore oil rig is figuratively burning under someone as he or she calls for emergency advice. Corporate headquarters offers an unusual in house service a cross-cultural management consulting team who respond to burning platform issues sent in remotely from managers around the globe. This team will determine the best course of action for five individual situations just emailed from Shanghai.

Keywords

Cross-cultural Management, US/Chinese Intercultural Communication, Cross-cultural Conflict Resolution, Individualism Authority (“Power Distance”).

Introduction

An effective way to understand and competitively use cultural differences in the workplace are cross-cultural models from international management and cross-cultural psychology. Chinese and American cultural values scores that highlight the similarities and differences between their respective cultures are particularly useful. Often the areas of greatest cultural value differences (areas where the scores are the widest apart) provide an indication where the greatest cross-cultural differences are most likely to surface in the workplace.

Cross-cultural models and parameters for analyzing culture differences go back to the beginning of modern culture studies in the early 1900s. A number of these are associated with the following:

1. Edward Hall (1959)

2. F.R. Kluckhorn and F.L. Strodtbeck (1960)

3. Andre Laurent (1983, 1986)

4. Geert Hofstede (1980, 2002, 2014)

5. Fons Tompenaars (1998)

6. The GLOBE project (House et al., 2004)

There are several contemporary cross-cultural models with strong empirical or solid research-based backgrounds. Of these the Hofstede model is the best known and most used in scholarly research. Hofstede has been called the “grandfather of cross-cultural management” and the “father of cross-cultural data bases” by Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner (1998). To highlight cultural differences between Chinese and US students, this paper uses numerical data from the work of Hofstede comparing attitudes and values held by 116,000 employees of IBM in 50 countries and three regions. Subsequently, Hofstede (1980) compared countries on four core dimensions: Power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance. Later he added a fifth (Long Term Orientation) and sixth (Indulgence) dimension to further analyze these cultural differences. Culture continues to be analyzed and studied as an important aspect of international business to this day (House et al., 2014; Stahl & Tung, 2015).

According to Hofstede (1980, 2002, 2014) Power Distance examines how people within a culture view power (superior/subordinate relationships). Cultures with high power distance presume that power is shared unequally and all people have a place in society. In lower power distance cultures, people strive for a more equal distribution of power and demand justification for inequalities. Individualism measures how much a person looks after himself versus a group (collectivist). The expectation of individualistic cultures is that the people will look after himself and his immediate family first. In contrast, collectivist societies have a tightly knit social group where they can expect people to look after one another in exchange for unquestioning loyalty. Masculinity focuses on the extent to which a society stresses achievement over nurture (femininity). In masculine societies, achievement, heroism, assertiveness and material rewards for success are the norm whereas feminine societies prefer cooperation, modesty and caring for others. Uncertainty avoidance measures a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. This dimension relates to the society’s comfort with the unknown. Cultures exhibiting high uncertainty avoidance maintain rigid codes of belief and Behaviour. Cultures low on uncertainty avoidance tends to me much more relaxed in this area. Long term orientation is when the society is focused on the future whereas short term orientation stresses the present or past, considering them more important. Finally, Indulgence measures the extent to which people try to control their desires and impulses. Indulgence societies allow for gratification of basic and natural human drives while restraint societies suppress gratification.

In analyzing Hofstede’s numerical data for this study, the authors determined that the key cross-cultural differences existed between China and the United States along two cultural value dimensions: Power distance (“PDI”) “Authority” will be used in this paper instead of “PDI” and individualism versus collectivism (“IDV”) (Table 1). We use these observed differences to offer insights into cultural differences as they extend to the workplace. Definitions of these national cultural dimensions are:

| Table 1 : Scores In The Dimensional Model | ||

| Dimensions | China | USA |

|---|---|---|

| PDI | 80 | 40 |

| IDV | 20 | 91 |

Source: Hofstede (Hofstede, The Hofstede Center 2014)

1. Power Distance (“PDI”)/Authority–measures the extent to which less powerful members of organizations accept an unequal distribution of power which in turn leads to hierarchical vs. egalitarian forms of human Behaviour.

2. Individualism (“IDV”) –measures the degree to which people in a country prefer to act as individuals or members of a group which in turn leads to group-oriented vs. individualistic forms of Behaviour.

Cross-Cultural Management Value: Authority (“Respect Culture”)

The first national culture dimension deals with authority and the degree of inequality among people that the population of a given country accepts as normal. In a high authority country like China, employees accept differences in power or inequality more willingly and have greater hierarchical tendencies. In a low authority country such as the United States, employees do not accept differences in power as willingly and have more egalitarian tendencies (Hofstede 2004).

The phrase “culture as frozen history” can be correlated with the fact that China’s high authority score is, in part, because 4,000 years of political centralization has led to a tradition of obedience. For example, the Chinese use of dynasty names to refer to periods in history illustrates the degree of emphasis and importance placed on centralized leadership. Chinese culture has nurtured the idea that authoritarian Behaviour is essential in order to maintain the stability of social systems.

Many Chinese rulers adopted Confucianism as a strategic tool to achieve social stability and civil justice (Leung and Wong 2001). According to traditional Confucian views, the stability of society rests on unequal relationships between people in a hierarchical social structure. Much of China’s culture reflects Confucian thought and places a great deal of importance on the hierarchy and harmony of social groups. The significance of a strongly hierarchical social structure is based on the idea that a harmonized society is created when every person knows and stays in their proper position. While treating people differently according to the social status is contrary to many Western ideals, it has been a tool used to maintain harmony and balance in China for thousands of years.

In terms of “Culture as frozen history” the United States is a much, much younger “teenage culture” country. In the beginning, the US was composed of more egalitarian political and religious dissident immigrants and later the extremely egalitarian, mobile pioneers and cowboys who developed modern American culture as they pushed farther and farther westward across a massive continent (Table 2).

| Table 2: Authority Dimension: Managerial Implications | |

| China (Score=80) | USA (Score=40) |

|---|---|

| More hierarchical leadership | More egalitarian leadership |

| More autocratic management style | More democratic management style |

| Top-down communication, low feedback culture |

Side-by-side communication, high feedback culture |

| Acquired professional status | Achieved professional status |

Match Eagles with Eagles

The Chinese are credited with the saying: “You must match eagles with eagles,” meaning people with ascribed status in High Authority cultures expect to be matched by individuals who have their same level of ascribed status. Although this concept appears to be fairly easy to understand and apply, the truth is that in the area of international business, each side of the Authority continuum will regularly be confused, angry and frustrated by differences with the opposite end of the Authority continuum.

For example, an American company will send a twenty-seven-year-old specialist (consultant, engineering expert, etc.) to meet with a fifty-five-year-old Chinese president of a client company, only to hurriedly call a cross-culture management consultant because the Chinese president “iced” or ignored the young American. In the spirit of “matching eagles with eagles,” it is more appropriate, at least initially, to send someone to call on the Chinese president who is closer to his/her ascribed status in terms of age and position. The key issue for professionals and management from Low Authority countries is to be acutely aware of these differences when hosting and/or working with executives from the high end of the Authority scale.

Cross-Cultrual Management Value: Individualism (“Relationship Culture”)

The individualism dimension provides an optimal understanding of Chinese/US differences in the workplace. Differences in East-West communication styles are profound and the difference between the two scores provides insight into the majority of the cross-cultural conflicts between Chinese and Western managers. The US is more individualistic than any other country in the world, while only three countries in the Hofstede databank (all in South America) are more collectivistic than the Chinese culture.

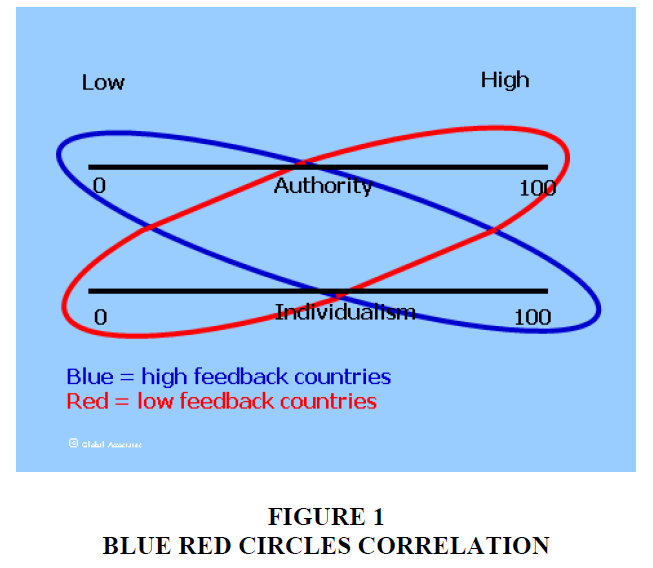

High individualism represents the degree to which people in a country prefer to act as individuals rather than as members of groups. High individualism exists when people define themselves primarily as separate individuals and make their main commitments to themselves. It implies loosely knit social networks in which people focus primarily on taking care of themselves and their immediate families (Adler and Gunderson 2008) (Figure 1).

The opposite, low individualism/collectivism, pertains to “societies in which from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetime continues to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty” (Hofstede 2002). Low individualism is characterized by tight social networks in which people strongly distinguish between their own group and other groups, as well as by their tendency to hold more common goals and objectives, than the high individualism goals that focus primarily on self-interest.

In low individualism societies such as China, a child learns to respect the group to which he or she belongs, usually the family and to differentiate between in-group members and out-group members (that is, all others outside of the family, regional ethnic group, locale, etc.). When these children grow up, they remain members of their in-group and expect the in-group to protect them when they are in need. In return, they are expected to give both a tremendous degree of loyalty to their in-group.

Low individualism societies are also known as “shame cultures” versus the “guilt cultures” of the high individualism. This is because there is a central tendency in group-oriented cultures to base their Behaviour more on the outward constraints or social mores of what the people around them think. This is where the famous “saving face” concept comes from–one can save face or loses face based on whether their outside group affirms or disaffirms them. In extreme individualism cultures, like the American, there is more of a central tendency to be more “individualistic,” and, to limit one’s Behaviour to internal “guilt” factors, i.e., usually the moral or social guidelines received growing up from one’s parents.

One of the fundamental reasons for China’s unusually low individualism is the emphasis on group relationships that arose with the country’s agrarian origins and the concomitant parameters of intense social contact (Table 3). Maintaining harmony with the immediate social environment and the family has extended to most facets of Chinese society.

| Table 3: Individualism Dimension: Managerial Implications | |

| China (Score=15) | USA (Score=91) |

|---|---|

| Indirect communication | Direct communication |

| Relationship oriented | Task oriented |

| Low or subtle feedback | High or required feedback |

| More context-based communication | More content-based communication |

Cross-Cultural Management Value: Authority/Individualim Correlation

High Authority cultures–85% of the world, including China will also rank as Low Individualism cultures, again, about 85% of the world, including China.

The combination tends to lead to much lower feedback as managers in the High Authority side are not used to taking initiative with their superiors, in that top-down communication structure. This hesitation in communicating upward diminishes feedback time even further when the Low Individualism dimension is added in. This because, in a “harmony” and relationship culture, people will be more cautious about communicating in any manner that might appear to be too direct or conflictful.

The Low Authority, more egalitarian American will tend to speak out regardless of higher status people being present. More feedback also comes much easier to the High Individual American as they are more direct and task-oriented in their natural communication patterns.

Cultrual Brokers/Intermediaries

There is a very important general disclaimer arising from the inherent limitations to anything written on cross-cultural management. “Book” knowledge can only deal with general, commonly repeated situations, while human Behaviour and culture are so complex that many management situations are very specific and unique only to that setting.

When the same puzzling Behaviour has been repeated many times and the manager suspects it has to do with culture differences, the ultimate advice for that cross-cultural manager is to go directly to a culture broker or culture intermediary. A culture intermediary is someone who has significant experience in both cultures involved in an intercultural workplace conflict. As opposed to a written material, generalizing about cross-cultural management, a cross-cultural broker can give immediate, specific advice about a particular work situation experienced by the person asking for help. Usually this is because cross-cultural brokers have themselves experienced and solved those same work situations, often many times before (Table 4).

| Table 4: Cross-Cultural Intermediares/Broker Types |

| 1. A fellow national of the manager’s culture who has lived and worked a significant amount of time in the other culture. |

| 2. A national of the other culture who has lived and worked a significant amount of time in the manager’s culture. In the case of the American manager in Chicago, he or she would look for: (1) Another American who has interacted significantly with Chinese, either in China or the US or (2) a local Chinese who has interacted significantly with Americans, either in China or in the US In the same manner, the Chinese manager in the US will look for: (1) An American colleague who has worked as an expatriate manager for several years in Shanghai or (2) a fellow Chinese at his golf club who attended graduate school in Los Angeles and is now working full-time in the US. Either of these persons would tend to be effective cross-cultural intermediaries concerning Chinese/American culture differences at work. Several actual quotes from Chinese who are trying to help Westerners understand their culture:•One word you never want to use when you come to China is “no”.•“It is harder for us to work with Americans than Europeans because Americans don’t understand the meaning of “yes”.•There is an old Chinese saying: “Westerners are very superficial?they believe what you say”. |

What type of person should an American cross-cultural manager look for as a culture intermediary/broker to help him or her better understand some puzzling incidents with a Chinese manager at their Chicago headquarters? What type of cross-cultural intermediary/broker would a Chinese manager look for while working in the USA?

An American manager, Michael Todd, is facing several urgent burning platform issues as he begins his new position in China. Previously, Michael has utilized his substantial experience in cross-cultural management to help facilitate international business. He recalls the single best piece of advice he received was to look for and use a cross-cultural broker whenever there is any pattern of puzzling incidents or Behaviour in the intercultural workplace. Since there are five critical situations that are extremely urgent, he decides to reach out for assistance to ensure that all matters are handled timely and in an appropriate manner.

Incident A: Mysterious Response

Since 1990, soon after we opened our first restaurant, we have had a strong relationship with Mr. Meng (pronounced “Mung”), a local Shanghai businessman in the clothing retail industry who also owns eight of our franchises. The association between Quicks and Meng has been long and mutually profitable well known within the company particularly because, after first entering China, he was the first local business leader to stand up to the government bureaucracy on our behalf and has consistently been there for Quicks ever since.

Recently, Mr. Meng has been suffering losses in his core business and begun to cover them by withdrawing more funds from his franchises than our agreement allows for. After a few months of this, Vice President Tom Boyd, in charge of Asian franchises and longtime friendly colleague of Mengs, decided to act. Tied up with other deadlines at headquarters, Boyd sent Quicks’ legal counsel on a fact-finding mission in order to discover what exactly had happened and to negotiate a compromise of some sort.

Mr. Meng had not previously heard of this lawyer and first learned of his presence in the country when he received a telephone call from the Shanghai Pudong International Airport saying, “I am one of VP Boyds’s legal advisors. He has asked me to find a solution to his problems with you.”

After that everything went south and we have no idea what happened. Mr. Meng immediately began delaying tactics, eventually refusing to meet Boyd’s emissary altogether and now is not responding to my telephone calls. (After spending four days cooling his heels in a hotel, the lawyer left Shanghai and returned to Oak Park headquarters.)

This can be a major problem for us as we have millions of yuan tied up in these franchises, cannot afford to have a little bit of red ink turn into a flood and Quicks needs a strong, sustainable relationship with Mr. Meng more than he needs one with us.

Question 1: How could have Quicks handled the situation more appropriately given the cultural differences between US and Chinese management. Additionally, what can Quicks do to remedy the situation?

Incident B: Feedback Again!

It is common knowledge that Western managers find it very difficult to get accurate feedback from Asians, especially under time constraints or other stressful business situations. I’m afraid I have no special insights on this issue; it certainly was not a problem in Quicks Europe, particularly The Netherlands, Germany, France and Italy where I was assigned.

We need a solution, however, by the end of today. I got off the telephone with an Oak Park executive who has been in Beijing for two days now and sounds a little desperate. I’m not privy to all the information from the top, but apparently headquarters is contemplating some new initiative worldwide in conjunction with our largest suppliers. They have sent key American executives to meet face-to-face with their national counterparts in major Quicks’ regions, to discover confidentially what the worldwide leadership feels about this new direction. Because of the huge resources involved in this strategic initiative, Oak Park doesn’t want to go forward until they get a definite reading of everyone’s full-hearted support.

The problem is this executive has been meeting all day with our two single largest suppliers, about fifteen top Chinese executives (Hsinchu Meats and Ta Hsueh Industries–commercial bakery) and is receiving only noncommittal answers and responses, neither for or against the new initiative. These non-answers are beginning to panic him because his return flight is in two days and he is expected to present a definite Chinese position soon after landing at O’Hare.

He called me because I’ve met most of these Chinese executives, but I can’t think of anything to suggest. After today’s conference call with your team, I promised the executive to call with concrete advice on how to proceed. Thanks.

Question 2: How might Quicks management approach the situation of non-committal answers? Is there a way to get the information they need?

Incident C: Office Violence

The third incident is most bizarre and literally happened this afternoon. A country manager at an international office has a trouble-shooting/firefighting role that sometimes bounces from general strategic issues down to individual personnel incidents. This is one of the latter.

Apparently, a young Chinese supervisor here in the Shanghai office lost control and physically attacked a Chinese accountant who works in the next office. It must have been caused by something serious, because when I ran in, the supervisor had the accountant on the floor and was kicking him badly. We pulled the supervisor off, called security to escort him out of the building and then I sat down with the top Chinese managers to determine what to do next.

I have an ex-Marine officer background and over fifteen years managerial experience with Quicks and felt 100 percent sure that this incident was a straightforward human resource issue, with nothing to do with cultural differences. It seemed like an easy decision along with a company policy of zero tolerance for all acts of personal violence and I was going forward with immediate dismissal of this supervisor.

So, I was taken aback when the several of the more experienced, senior Chinese managers, strongly advised me that we not fire the supervisor. When I asked for their recommendation, they suggested having him apologize in front of the entire headquarters’ staff and, in addition, have him praise the accountant whom he had attacked. (I did appreciate, later, these same managers making a point of saying they would support me in whatever final decision I made.) I’m leaning strongly toward my original instinct to fire the supervisor.

Question 3: Should the supervisor fire the employee immediately or demand a public apology?

Incident D: Negotiation Blues

One of my main projects after arriving here is to head negotiations with the government on increasing the amount of financial dividends Quicks is allowed to repatriate out of China. It is a politically sensitive issue, so we have been proceeding with caution over these last weeks. Still, the negotiations have been going quite well, considering the tough reputation Chinese have as negotiators and we were on schedule.

Going well until now that is. Last week was crucial, so my boss flew in from Oak Park and joined our negotiating team for the final stretch. She fit in well with the negotiating process and the Chinese side appeared to have a lot of respect for her style and knowledge of the issues. Nothing seemed unusual until the second day after she joined us when all of a sudden the government team switched and started using heavy stall tactics. For example, they dramatically slowed the process by saying, “We can’t continue until we go back to our superiors with your amendment and get their permission for the next stage.” They also said, “Our superiors are not happy with item #6 so we need to revisit it,” even though we had reached complete agreement on item #6 weeks ago.

I have enough experience to recognize when negotiations are disintegrating, but I can’t pinpoint what exactly is causing the deterioration and weakening our team’s position so quickly. In the last two days the only changes, none of which seem consequential, from our side were the following:

1. My boss joined our negotiating team for the first time. I have kept her up-to-date daily during these past weeks and she has also met the government team at the beginning of the process.

2. A couple of times, in the negotiating process with the Chinese, I challenged my boss on something she said, but she and I relatively quickly worked out the differences between us.

3. Last evening, we arranged to host the government team at a banquet and tried our best to make sure it was equivalent in cost and status to the banquet they had previously held for us.

4. The government team had asked if they could add two more members to their negotiating team, but we said no. We didn’t have two more people with enough expertise to join our side and we have been negotiating successfully enough up to now with the present count.

This incident is particularly important to me because I lead the Quicks team on the ground and the negotiation’s success or failure will reflect on me personally. I’ve lost sleep going over and over the four changes listed above but can’t understand how any one of them could account for this sudden shift and uncertainty demonstrated by the government team. If you can help me on this one, I will owe you big.

Question 4: Which incident had the biggest impact on the negotiation process?

Incident E: To Bribe, Not To Bribe Or How To Bribe?

This last case is a cultural conundrum that has been ongoing for months, with two expat managers before me completely stumped by the situation. I’d like to move on it but, with bribery being such a sticky situation, I have run out of options. Is it possible there is something we can do from a cultural standpoint to find a workable solution? Because of the large amount of money involved in the total transaction, head office has budgeted up to US $150,000 for me to use at my discretion.

The People’s Liberation Army will pay for a single fast-food franchise, on a turnkey basis, at several military bases in China’s east coast provinces. Currently, Quicks is in the running with only two other US competitors: Kentucky Fried Chicken and Pizza Hut. We have a good edge due to the solid reputation Quicks has carefully built up in China.

The total amount to be paid by the Chinese is US $10 million up front and US $12 million when the whole franchise is turned over to them after two years, making the final deal a lucrative US $22 million plus an ongoing presence within the Chinese military establishment. Very nice from the business side, but it has been held up all this time by a government official who is asking for a US $800,000 “personal commission” before letting the deal go through. The official is only an upper mid-level bureaucrat but, unfortunately, he is also the individual who signs off on the final deal and he has not budged an inch from his original demands.

We know KFC and Pizza Hut have not paid the bribe, since the offer is still open, but we expect they are working hard on some way to circumvent this official. So, if ever an understanding of cross-cultural management can give us a competitive advantage in the global marketplace, this is the time and place.

Question 5: How should Quicks handle this bribery situation?

References

- Adler, N.J. & Gunderson, A. (2008). International dimensions of organzational behaviour. Mason, OH: Thomson Higher Education.

- Hall, E.T. (1959). The silent language. New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc.

- Hofstede, G. (2002) Culture and organizations:software of the mind. Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill.

- Hofstede, G. (1980) Culture's consequences: International differences in work related values. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- Hofstede, G.(2014). The Hofstede Centre. Retrieved from http://geert-hofstede.com/countries.html

- House, R.J., Hanges, P.J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P.W. & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership and organizations. The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publication.

- House, R.J., Dorfman, P.W., Javidan, M., Hanges, P.J. & Sully deLuque, M. (2014). Strategic leadership across cultures: GLOBE study of CEO leadership behaviour and effectiveness in 24 countries. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Kluckhohn, C. & Strodtbeck, F. (1960). Vairations in value orientations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Laurent, A. (1986). The cross-cultrual puzzle of international human resource management: A field in its infancy. Human Resource Management, 25(1), 91-102.

- Leung, T.K. & Wong, Y.K. (2001). Guanxi: Relationship marketing in a chinese context. Binghamton, NY: International business press.

- Levi-Strauss, C. (1963). Structural Anthropology. New York: Basic Books.

- Mead, R. (2005). International management: Cross-cultural dimensions. 3rd Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Stahl, G. & Tung, R. (2015). Towards a more balanced treatment of cluture in international business studies: The need for positive cross-cultural scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(4), 391-414.

- Trompenaars, F. & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global business. New York: McGraw-Hill.