Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 1S

Career Growth, Career Concern, Organizational Commitment and Turnover Intention in Universities of Jordan

Shaima A.Kh. Barakat, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Ahmad Bashawir Bin Haji Abdul Ghani, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Mohammed R A Siam, Universiti Utara Malaysia

Keywords

Turnover Intention, Organizational Commitment, Career Growth, Career Concern, Academic Staff.

Abstract

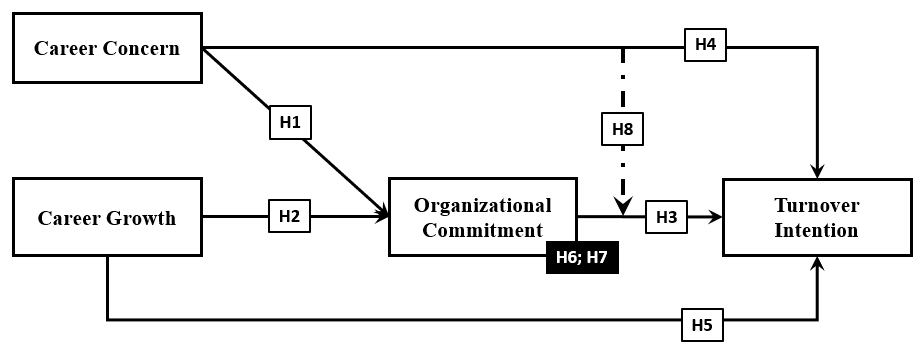

The study examines the impact of career concern and career growth on turnover intention and organization commitment, besides the moderation impact of career concern. This particular study's research framework has career concern and career growth as independent variables that have a direct impact on turnover intention and indirect impact through an organizational commitment to turnover intention. Besides, career concern is a moderator to the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention. The population of the study is any academic employee who is working in public universities of Jordan. Based on different sources, the number of Universities is around 10. An estimation of the academic workforce working in those Universities is 2500 employees. The actual sample size is 288 employees. The distributed survey is 370, distributed by using face-to-face data collection methods in a convenient sample selection technique in 2019. Overall, results show that the Turnover Intention (TI) model has a satisfactory predictive power and a medium predictive relevance (power of 42.3%, and relevance of 31.7%). Organizational commitment (OC) illustrates a satisfactory predictive power and a medium predictive relevance (power of 36.4%., and relevance of 25.9%). For the predictors of turnover intention, the two antecedent variables have significant relationships, and the ascending rank of the variables based on the path coefficient value is career growth (0.424) and career concern (0.198). Career concern has no significant impact on organizational commitment, but it has a significant relationship to the organizational commitment with a path coefficient of 0.377. Organizational commitment has a partly mediation impact on the relationship from the career growth but has no mediation impact for the relationship from career concern. Career concerns have no moderating effect on the proposed relationship.

Introduction

With the increase in globalization, organizations are facing several issues, including turnover. Turnover has risen to be a crucial issue for the organization. Two types of drawbacks are imposed on organizations because of employee turnover. The first drawback involves selection, recruitment, placement, and loss of worked time. The second drawback includes indirect costs such as lower performance of the organization. A number of employees are changing their jobs to avail better opportunities. The trends in the market are changing, and the perception of employees changes as well. Therefore, switching jobs for better incentives and benefits or position is considered a usual thing. This is not regarded as something negative as employees aim at success in their careers. An individual who works with a single employer in his career is a rare case (LeBlanc, 2018). In this highly competitive business environment, employee retention has become is not an easy task.

These HRM methods are observed to be an important way to establish a strong relationship with the employees, which in terms leads to a sturdy sense of commitment coming from the employees towards the company (Vanhala & Ritala, 2016). For that reason, it can be summarized that when a company invests in an effective wage system, good training and development program, effective performance monitoring system, and Career Growth (CG) chances of their employees so they can improve their qualified skill-set and growth, these employees will not easily leave the company and they will have a high sense of commitment towards it (Dumont et al., 2017). Therefore, to be able to understand the factors that play a role in employees' turnover decisions, more focus should be put on the relationship between HRM practices, Career Growth (CG) practices, and ETI (Hassan, 2016).

According to Jehanzeb (2015), study results provide strong support for the hypothesis that is a negative relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention (Anil & Satish, 2016). As a mediator predictor of turnover intention, Organizational commitment is defined as a view of an organization's member's psychology towards his/her attachment to the organization that he/she is working for (Almutairi, 2016). Organizational commitment plays a pivotal role in determining whether an employee will stay with the organization for a longer time and work passionately to achieve the organization's goal. Therefore, the turnover intention will be highly related to the causal variables, increasing the commitment mediating role (Khalili, 2017).

In order to deal with the issue of employee turnover, several researchers have recognized the crucial role played by human resource management practices in retaining employees (Nawaz et al., 2019; Kadiresan et al., 2015; Long et al., 2014). However, an employee's relation with an organization is altered through career growth and human resource management practices (King, 2016; McElroy & Weng, 2016). Through these practices, employees can understand the employment terms such as how jobs are advertised, the reputation of an organization reflected through the process of recruitment interviews, while career growth could be defined as professional development in the sense of becoming more important or bigger. A person can achieve career growth by specifying goals and objectives to achieve within working in a specific job or within a certain time (Tzabbar et al., 2017). The employees evaluate organizations in terms of the training opportunities, career growth opportunities, performance appraisal, promotion, and other benefits it provides. All these factors convey a strong message to the employees about their expectations from the organization and the organizational expectations from them (Donate et al., 2016).

Career concerns appear in situations where firms do not know a worker's future productivity, but they learn about it by observing his performance (Ebrahimi et al., 2016). Career concerns refer to concerns about one's vocational future in terms of time perception, anticipation, and orientation (Latimaha et al., 2019b). In other words, career commitment is a sign of insisting on achieving the individual's career goals (Latimaha et al., 2019a). Individuals committed to their careers concern with their careers regardless of the working conditions and colleagues, even their organizations, and vice versa. Which in this case, Career concerns can impact the commitment on its relationship with a turnover of the employees turnover (Vanhala & Ritala, 2016)

The aim of the study is to examine the impact of career concern and career growth on turnover intention and organization commitment, besides the moderation impact of career concern.

Literature Review

Conceptual Framework

This particular study's research framework has career concern and career growth as independent variables that have a direct impact on turnover intention and indirect impact through an organizational commitment to turnover intention. In addition, career concern is a moderator to the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention Figure 1.

Concept of Employee Turnover

Employee turnover is obtained by the total number of employees that leave an association, substituted by the company's new employees (Zhang, 2016). Evaluating employee turnover could be practical to companies that desire to examine causes for turnover or determine the cost-to-hire for spending plan functions. It will also help HR know the reasons behind employee turnover (Rani & Mishra, 2018; Zhang, 2016).

Although different sorts of turnover exist, the standard definition is that turnover occurs when the job relationship ends. When describing that an employee left the company, there are several terms such as attrition as well as turnover. In general, attrition means that the employee left the company voluntarily; and the company will not hire another person to take that vacant place (Gabriel et al., 2020).

Employee turnover has become a major concern for employers. It reflects that it has become a great challenge for modern practitioners as well as researchers because of some negative results concluding economic losses for an organization, lower employee productivity, job efficiency, etc. (Mowday et al., 2013).

In 2016, a study was conducted by Han, et al., on employee turnover intention. The results of the study revealed that employee turnover could be voluntary or involuntary. When the employer asks the employee to quit the job, factors such as low performance or inappropriate attitude this is called involuntary turnover (Zhang, 2016). However, when an employee wants to leave the organization because of some reason, this is called voluntary turnover. Several researchers have observed employee turnover and its management. The intention to leave a job is referred to as turnover intentions is that is linked with voluntary turnover (Al-dalahmeh et al., 2018). The concept was defined by Price (2001) as the behavior that results in the movement of employees from one organization to another. However, the turnover intention has been signified. Moreover, the turnover intention has been defined as the individuals' estimated probability for leaving the organization permanently at some point (Mowday et al., 2013). Joo, et al., (2015) defined turnover intention as a time-consuming process for thinking to quit the job and find a new one.

Most of the research studies available are about turnover intention instead of actual employee turnover. It is very hard to evaluate the actual employee turnover behavior. Most of the times, institutions are unable to divulge the info relating to employees (Argyris, 2017) and consequently, it is challenging to acquire access to the employee who has actually left an organization and analyzed factors that aided in them choosing to leave the job (Aldrich & Wiedenmayer, 2019). However, Chung, et al., (2017) expressed that the intention of turnover can alternatively be used in place of actual turnover behavior; and there are many research studies on this specific topic, even some researchers have replaced the term "turnover intention" with the term "intent to leave" (Kok et al., 2017). At the same time, others utilized the term "perceived value of leaving" (Su & Chan, 2017). Regardless, all these terms possess the exact same meaning, and hence, within this research study, "employee's turnover intention" and "employee intention to leave" are a reference to "turnover intention."

It has been revealed by researchers that there is a positive correlation between turnover intention and actual turnover behavior of employees (Huang et al., 2016). The two variables cannot measure the turnover intention in a similar way. Several results are contradictory considering the independent variable, such as the Perception of Organizational Support (POS), which signifies the difference between the outcome variable and intention to leave. It has been observed by Wong, et al., (2015) that there is a significant correlation between turnover intention and POS, but it is not related to the actual turnover.

A precise explanation of employee outcomes is given by actual turnover (Rubenstein et al., 2018). Some cross-sectional researches have examined the intention to leave the organization by taking satisfaction for performance appraisals as independent variables and turnover intention as the dependent variable (Cohen et al., 2016). Employees having turnover intention may quit the job at some time in the future. Therefore, longitudinal studies of the variables being examined would have used preferably as actual turnover in a future phase (Hale et al., 2016). With regard to turnover intentions and actual turnover, Chan, et al., (2016) found the relationship between affective commitment to managers and turnover intentions in two samples, whereas, in the third sample, affective commitment to managers was the only important predictor of actual turnover. In this current study of turnover, the actual turnover measurement is exceptionally challenging due to a lack of information. Moreover, when the employees left the organization, they are unlikely to get traced, and hard to gain approach them. Furthermore, the survey response rate is frequently low due to the mentioned reasons (Rossi et al., 2018). Moreover, organizational databases are not accessible by external researchers or might be imperfect or incorrect due to a number of reasons. Therefore, Cohen, et al., (2016) revealed that turnover intention could be carefully used as a substitute for actual turnover behavior. Inconsistent with this idea, Wong and Laschinger (2015) contended that the turnover intention is frequently used as a final outcome variable in turnover research.

Almost every organization is facing the issue of employee turnover, and it has become a serious issue. Organizations need to be creative in managing this issue through the identification of several reasons causing this (Grissom et al., 2012). Several researchers have explained the reasons for the decision of the employee to leave the organization (Nawaz & Pangil, 2016). Most of the research on turnover intention has been on the use of different demographic, organizational, and contextual factors related to work attitudes as explanatory variables. Some of the organizational factors that significantly impact employee's intention to leave include "organizational justice" (Baruch et al., 2016).

Besides organizational factors, there are some job-related factors that relate to turnover intention, such as person-organization suitability (Son & Ok, 2019), job incompatibility (Thevenin et al., 2017), work-value congruence (Huhtala & Feldt, 2016), job autonomy (Van-Yperen et al., 2016), pay and promotional chances (Jonasson, 2013), job alternatives, (Huang et al., 2017). Attitudinal factors such as satisfaction, OC, perceived organizational support, and job involvement (Kurtessis et al., 2017) and citizenship behavior (Piccolo et al., 2018), were found to affect turnover intention. Other turnover intention predictors found in this study were job performance (Cheng et al., 2016); absenteeism (Bennedsen et al., 2018); and biographical characteristics (Mahajan, 2015). Basically, there are many individuals, job-related and organizational factors that have been found to affect the employee's intention to leave the organization. These findings provide good insights to the organizations regarding minimizing turnover in organizations. Besides all these factors, there is an increasing body of research has also examined the relationship between HRM practices, CG, and turnover intention.

Concept of Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment is actually described as the client's mental view of their connection to an organization they work for it. Organizational commitment participates in a critical part in identifying whether an employee will spend a long time working in the company and the amount of work and energy they will invest to achieve the company's goal (Kulkarni & Kothelkar, 2019).

If an organizational commitment is determined, then elements such as employee complete satisfaction, employee engagement, organization of leadership, task functionality, task instability, and others can be predicted. An employee's level of commitment towards his/her job is vital to recognize from an administration's POV so as to be able to recognize their devotion to the tasks designated to all of them daily (Anitha, 2014; Chiaburu et al., 2013).

High levels of organizational commitment can be measured through enhanced profitability, boosted productivity, employee retention, consumer satisfaction metrics, a decrease in consumer complaints, and above all, improving the work environment lifestyle; which are all the elements that a company is aiming for, however, the question lies on how can a company achieve those.

A distinguished theory in organizational commitment is actually the Three-Component Model (TCM). Depending on this theory, there are actually three distinctive components to organizational commitment (Shrivastava, 2018):

• Active commitment: It is the emotional attachment that the employee feels towards the company. Active commitment additionally means an employee is not just satisfied with his job but also likes to interact and do the activities required such as meeting, giving beneficial inputs or pointers that will certainly help the association, and more (Shrivastava, 2018).

• Continuation Commitment: This basically means that an employee's commitment towards the company is because it would be very costly and inconvenient to leave the job. Their feeling of commitment comes from the fact that they spent much time in the company and already established their place there. For example, an employee who spent years working in a company develops a type of attachment to their office, and eventually, this could become a reason why they won't leave the company (Shrivastava, 2018).

• Normative Commitment: It is the type of commitment where the employee feels obligated to remain in the company. So, what are actually the aspects that aided this form of commitment? Is it an ethical obligation where they wish to stay since another person counts on them? Or is it because they are comfortable with the way they are being treated and are afraid to try another company and eventually get disappointed? (Shrivastava, 2018).

Concept of Career Growth

In business, world growth indicates "higher movement," which is the perspective of the organization. However, growth to an employee means moving into administration. Usually, employees will slowly reach higher positions in a company. For example, going from a basic desk job to being a manager and is the meaning of growth to an employee (Vinkenburg & Weber, 2012).

Career growth means that the person becomes more skilled or has a higher position and in general becomes more important; it is put through goals that the employee set for him/herself during their job. Working towards career growth can help the employee always try their best to achieve their goal (Wandera, 2019).

Career growth is usually mixed with another term which is career development. Career development can be defined as "a procedure in which something improves (primarily beneficial) and step to another level, the improvement can be physical, psychological or social" (Lent & Brown, 2013). When a person embraces career development, they take time and give more energy to improve and become better. They are aiming towards becoming experts in their field or a business. Career development has to do with pushing to become far better and improving individual durability’s and skill-sets (Tieger et al., 2014).

Therefore, if the employee wants to advance more in their job, they need to focus on career development and career development. Both of them complement each other to help the employee in the best possible way (Carter et al., 2011).

Concept of Career Concern

Career concern refers to concern about one's vocational future in terms of time perception, anticipation, and orientation (Öncel, 2014). Anderson & Niles' (1995) study of "Career and personal concerns expressed by career counseling client" determined that a career concern can be handled the same as any other work-related concerns. However, concerns that are considered non-work related lacked any reference to work (Anderson & Niles, 1995). The researchers themselves admitted that their suggested categories of career concerns appeared to be narrowly focused around work and occupation, so they also included a category to allow for a mixture of career and non-career concerns (Allen et al., 2020).

An individual goes through different stages of development in this career life. A theory was suggested by career stage theory. This theory indicates that people go through different stages of career development in their life based on their needs, intention, desires at the respective career stages (Hartung & Santilli, 2016). There are different psychological determinants and fundamental behavior linked with every stage in the career of an individual. This is irrespective of the background, experience, or employment of the individual.

Four stages of a career have been (Bakke et al., 2020; Hoffman & Schwartz, 2020). Scholars argued that an individual selects a job and an organization for starting his career in the initial stage related to his interest. At this time, the individual wishes to learn about the organizational culture and evaluate the match between his skills and those required by the organization. At the same time, different alternative options are explored by the individual after the initial employment year. This may influence him to switch to other organizations (Hoffman & Schwartz, 2020; Morgeson et al., 2019). The next stage is the stage of transition. In this stage, the concern of employees is to improve their knowledge and abilities for being successful (Bakke et al., 2020). The employees have great enthusiasm related to the work and job. The third stage is the career-building stage, in which the focus of employees is shifted to improve their position in the organization. Employees aim at being promoted in the organization or look for these opportunities in other organizations. The fourth stage is the late-career stage, in which the focus of the employee is on their current positive and retirement life (Bakke et al., 2020).

Methodology

The study assumed that the turnover intention, organizational commitment, career concern, and career development could be measured in numbers, and prediction can be acquired from the analysis. Therefore, the study belongs to the positivism philosophy, deduction approach, quantitative methodology, empirical survey passed study, used cross-sectional data, and original data.

The population of the study is any academic employee who is working in public universities of Jordan. Based on different sources, the number of Universities is around 10. An estimation of the academic workforce working in those Universities is 2500 employees. The actual sample size is 288 employees. The distributed survey is 370, which was distributed by using face-to-face data collection methods in a convenient sample selection technique in 2019.The survey was organized to ask the questions in Likert-5 format. Likert 5 questionnaire style has been used in social science studies for a long time and proved to be a suitable style for measuring human perceptions.

Career concern was measured with a 12-item scale by Perrone, et al., (2003). Career growth professional ability development) is a 15- item scale by Weng & Hu (2009) was employed. This study defined organizational commitment as the commitment of individual faculty to academic institutions. OC, a 6-items scale by Gould & Davies (2005), was employed.

The turnover intention was measured with a 5-item scale by Wayne et al., (1997) was adapted. Structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques are used for statistical data analysis via the SmartPLS software package, which is used in management and social science studies such as (Salem & Alanadoly, 2020; Salem & Salem, 2018).

Findings

Validity and Reliability of Constructs

Many measures have been administered, such as composite reliability, outer loading, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, to ensure the dimension model's reliability and validityl (Hair et al., 2016; Sekaran & Bougie, 2016). Some items were actually eliminated on the general rule for outer loading and cross-loading; thus, four items were deleted. Outer loading for all various other items is above 0.708, along with no cross-loading coming. Consequently, indicator reliability is actually accomplished.

As displayed in Table 1, composite reliability is evaluated through Cronbach's Alpha plus all market values tower the cut-off value of 0.70. Consequently, the reliability of the size model is actually accomplished. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) worth’s tower 0.5. Consequently, convergent validity is achieved. Finally, Table 2 shows the Fornell-Larcker criterion matrix, which indicates that, no discrimination validity issues are

| Table 1 Constructs Reliability and Validity |

||

|---|---|---|

| Construct | AVE | Cronbach's alpha |

| Career Concern (CC) | 0.665 | 0.823 |

| Career Growth (CG) | 0.678 | 0.897 |

| Organizational Commitment (OC) | 0.689 | 0.91 |

| Turnover Intention (TI) | 0.61 | 0.853 |

| Table 2 Discriminant Validity – Fornell-Larcker Criterion |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | CG | OC | TI | |

| CC | 0.901 | |||

| CG | 0.456 | 0.825 | ||

| OC | 0.562 | 0.121 | 0.837 | |

| TI | 0.122 | 0.032 | 0.173 | 0.791 |

Relationships Examinations and Discussions

Table 3 shows the predictive power of the proposed model. For the purpose of assessing the power of the model construct in predicting the outcome variables, predictive power R2 and predictive relevance were used (Hair et al., 2016). The main dependent variable, Turnover Intention (TI), illustrates a satisfactory predictive power and a medium predictive relevance. As seen in the table, the related R square value is 0.423 (a power of 42.3%), and the related Q square is 0.317 (a relevance of 31.7%). The moderate variable, Organizational Commitment (OC), illustrates a satisfactory predictive power and a medium predictive relevance. As seen in the table, the related R square value is 0.364 (a power of 36.4%), and the related Q square is 0.259 (a relevance of 25.9%).

| Table 3 Predictive Power And Predictive Relevance Of Proposed Model |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Power | Predictive Relevance | |||

| R Square | Status | Q Square | Status | |

| Organizational Commitment | 0.364 | Satisfactory | 0.259 | Medium |

| Turnover Intention | 0.423 | Satisfactory | 0.317 | Medium |

Table 4 shows the findings of the relationships between the variables. The rule of thumb to accept or reject the relationship is either the p-value less than 0, 05 or the t statistics is more than 1.98 (Hair et al., 2015). The relationship between OC and TI is significant, with a path coefficient of 0.522. For the predictors of turnover intention, the two antecedent variables have significant relationships, and the ascending rank of the variables based on the path coefficient value are; CG (0.424) and CC (0.198). For the predictors of organizational commitment, career concern has a p-value of 0.114, which is above the threshold value of 0.05; therefore, career concern has no significant impact on organizational commitment. However, career growth has a significant relationship to organizational commitment, with a path coefficient of 0.377.

| Table 4 Path Coefficient Assessment Of The Direct Relationships |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | P Value (one tailed) | Status |

| H1 | CC à TI | 0.198 | 0.044 | 2.554 | 0.014 | Significant |

| H2 | CG à TI | 0.424 | 0.048 | 6.82 | 0 | Significant |

| H3 | OC à TI | 0.522 | 0.046 | 17.459 | 0 | Significant |

| H4 | CC à OC | 0.102 | 0.034 | 1.556 | 0.114 | Non- Significant |

| H5 | CG à OC | 0.377 | 0.051 | 5.817 | 0 | Significant |

Table 5 shows the path coefficient assessment for the mediating effects. Career concern has no significant impact on the mediator; therefore, the relationship from career concern to turnover intention cannot be mediated by the organizational commitment. However, career growth has a significant direct and indirect effect with a total effect of 0.645. Therefore, organizational commitment has a partly mediation impact on the relationship from the career growth but has no mediation impact for the relationship from career concern.

| Table 5 Path Coefficient Assessment of The Mediating Effects |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | Mediation |

| H6 | CC à OC à TI | 0.102 | 0.103356 | 0.301356 | No mediation |

| H7 | CG à OC à TI | 0.377 | 0.221328 | 0.645328 | Partly Mediation |

Table 6 shows the path coefficient assessment with T Statistics values' values for the moderating variable career concern. Respectively, the p-value and t statistics values are out of the threshold acceptable values because 0.179 is out of the 5% significance level. Therefore, career concern has no moderating effect on the proposed relationship.

| Table 6 Moderation Assessment of Management Support |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path Coefficient | Standard Deviation | T Statistics | P-Value (one-tailed) | Status | |

| CC * (OCà TI) | 0.039 | 0.043 | 1.381 | 0.179 | Non-Significant |

Overall, results show that the Turnover Intention (TI) model has a satisfactory predictive power and a medium predictive relevance (power of 42.3%, and relevance of 31.7%). Organizational Commitment (OC) illustrates a satisfactory predictive power and a medium predictive relevance (power of 36.4%., and relevance of 25.9%). For the predictors of turnover intention, the two antecedent variables have significant relationships, and the ascending rank of the variables based on the path coefficient value is; career growth (0.424) and career concern (0.198). Career concern has no significant impact on organizational commitment, but it has a significant relationship to the organizational commitment with a path coefficient of 0.377. Organizational commitment has a partly mediation impact on the relationship from the career growth but has no mediation impact on the relationship from career concern. Career concerns have no moderating effect on the proposed relationship.

Contributions and Recommendations

The study contributes to the knowledge of turnover intention, organizational commitment, career growth, and careen concern in the university's academic staff. The proposed combination of variables, especially the emphasis on turnover intention as the dependent variable and organizational commitment as a mediator besides the inclusion of career concern and career growth, is another theoretical contribution, especially when it is applied in the university academic staff context. The study also adds knowledge about turnover intention and its relationship with career growth and career concern in the Jordanian Public Universities. This study is limited to the empirical examination of the Jordan public universities; however, replicating the same design with the same research design, but in a different category of universities and in different countries, will provide support for the model validity and generalization of the results. The results show that career concern has no moderating impact besides having no impact on the organizational commitment; these results need more investigation by interviewing experts to explain that. The model can also explain up to 42% of the turnover intention variance and 36% of the organizational commitment; scholars are welcome to investigate more antecedents to increase the model power and provide a strong explanation model.

References

- Al-dalahmeh, M., Khalaf, R., & Obeidat, B. (2018). The effect of employee engagement on organizational performance via the mediating role of job satisfaction: The case of IT employees in Jordanian banking sector. Modern Applied Science, 12(6), 17-43.

- Aldrich, H.E., & Wiedenmayer, G. (2019). From traits to rates: An ecological perspective on organizational foundings. In seminal ideas for the next twenty-five years of advances. Emerald Publishing Limited, 61-97.

- Allen, N., Magni, G., Searing, D., & Warncke, P. (2020). What is a career politician? Theories, concepts, and measures. European Political Science Review, 12(2), 199–217.

- Almutairi, D.O. (2016). The mediating effects of organizational commitment on the relationship between transformational leadership style and job performance. International Journal of Business and Management, 11(1), 231.

- Anderson, W.P., & Niles, S.G. (1995). Career and personal concerns expressed by career counseling clients. The Career Development Quarterly, 43(3), 240–245.

- Anil, A.P., & Satish, K.P. (2016). Investigating the relationship between TQM practices and firm's performance: A conceptual framework for Indian organizations. Procedia Technology, 24, 554-561.

- Anitha, J. (2014). Determinants of employee engagement and their impact on employee performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management.

- Argyris, C. (2017). Integrating the individual and the organization. Routledge.

- Bakke, I.M., Barham, L., & Plant, P. (2020). As time goes by: Geronto guidance. In career and career guidance in the nordic countries. Brill Sense, 339–355.

- Baruch, Y., Wordsworth, R., Mills, C., & Wright, S. (2016). Career and work attitudes of blue-collar workers, and the impact of a natural disaster chance event on the relationships between intention to quit and actual quit behaviour. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 459-473.

- Bennedsen, M., Tsoutsoura, M., & Wolfenzon, D. (2018). Drivers of effort: Evidence from employee absenteeism. Journal of Financial Economics.

- Carter, G.W., Cook, K.W., & Dorsey, D.W. (2011). Career paths: Charting courses to success for organizations and their employees. John Wiley & Sons, 32.

- Chan, S.H., Mai, X., Kuok, O.M., & Kong, S.H. (2016). The influence of satisfaction and promotability on the relation between career adaptability and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 167-175.

- Cheng, C., Bartram, T., Karimi, L., & Leggat, S. (2016). Transformational leadership and social identity as predictors of team climate, perceived quality of care, burnout and turnover intention among nurses. Personnel Review, 45(6), 1200-1216.

- Chiaburu, D.S., Peng, A.C., Oh, I.S., Banks, G.C., & Lomeli, L.C. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of employee organizational cynicism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(2), 181–197.

- Chung, E.K., Jung, Y., & Sohn, Y.W. (2017). A moderated mediation model of job stress, job satisfaction, and turnover intention for airport security screeners. Safety science, 98, 89-97.

- Cohen, G., Blake, R.S., & Goodman, D. (2016). Does turnover intention matter? Evaluating the usefulness of turnover intention rate as a predictor of actual turnover rate. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 36(3), 240-263.

- Donate, M.J., Peña, I., & Sanchez de Pablo, J.D. (2016). HRM practices for human and social capital development: effects on innovation capabilities. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(9), 928-953.

- Dumont, J., Shen, J., & Deng, X. (2017). Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Human Resource Management, 56(4), 613–627.

- Ebrahimi, P., Moosavi, S.M., & Chirani, E. (2016). Relationship between leadership styles and organizational performance by considering innovation in manufacturing companies of Guilan Province. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 230, 351–358.

- Gabriel, P.I., Biriowu, C.S., & Dagogo, E.L.J. (2020). Examining succession and replacement planning in work organizations. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 5(2).

- Gould-Williams, J., & Davies, F. (2005). Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes: An analysis of public sector workers. Public management review, 7(1), 1-24.

- Grissom, J.A., Nicholson-Crotty, J., & Keiser, L. (2012). Does my boss's gender matter? Explaining job satisfaction and employee turnover in the public sector. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22(4), 649-673.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Hair, J.F., Wolfinbarger, M., Money, A.H., Samouel, P., & Page, M.J. (2015). Essentials of business research methods. Routledge.

- Hale, D., Ployhart, R.E., & Shepherd, W. (2016). A two-phase longitudinal model of a turnover event: Disruption, recovery rates, and moderators of collective performance. Academy of Management Journal, 59(3), 906-929.

- Hartung, P.J., & Santilli, S. (2016). The theory and practice of career construction. In Career Counselling. Routledge, 192–202.

- Hassan, S. (2016). Impact of HRM practices on employee's performance. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 6(1), 15–22.

- Hoffman, N., & Schwartz, R.B. (2020). Learning for careers: The pathways to prosperity network. Harvard Education Press.

- Huang, S., Chen, Z., Liu, H., & Zhou, L. (2017). Job satisfaction and turnover intention in China: The moderating effects of job alternatives and policy support. Chinese Management Studies, 11(4), 689-706.

- Huang, Y.H., Lee, J., McFadden, A.C., Murphy, L.A., Robertson, M.M., Cheung, J.H., & Zohar, D. (2016). Beyond safety outcomes: An investigation of the impact of safety climate on job satisfaction, employee engagement and turnover using social exchange theory as the theoretical framework. Applied ergonomics, 55, 248-257.

- Huhtala, M., & Feldt, T. (2016). The path from ethical organizational culture to employee commitment: Mediating roles of value congruence and work engagement. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 1.

- Jehanzeb, K., Hamid, A.B.A., & Rasheed, A. (2015). What is the role of training and job satisfaction on turnover intentions? International Business Research, 8(3), 208.

- Jonasson, A.K. (2013). The EU's democracy promotion and the Mediterranean neighbors: Orientation, ownership and dialogue in Jordan and Turkey. Routledge.

- Joo, B.K., Hahn, H.J., & Peterson, S.L. (2015). Turnover intention: the effects of core self-evaluations, proactive personality, perceived organizational support, developmental feedback, and job complexity. Human Resource Development International, 18(2), 116-130.

- Kadiresan, V., Selamat, M.H., Selladurai, S., Ramendran, C.S., & Mohamed, R.K.M.H. (2015). Performance appraisal and training and development of human resource management practices (HRM) on organizational commitment and turnover intention. Asian Social Science, 11(24), 162.

- Khalili, A.M. (2017). Development of sustainable performance model based on LM, QMS, SOFT TQM, and EMS: Malaysian context.

- King, K.A. (2016). The talent deal and journey: Understanding how employees respond to talent identification over time. Employee Relations, 38(1), 94-111.

- Kok, M.C., Ormel, H., Broerse, J.E., Kane, S., Namakhoma, I., Otiso, L., ... & Dieleman, M. (2017). Optimising the benefits of community health workers' unique position between communities and the health sector: A comparative analysis of factors shaping relationships in four countries. Global public health, 12(11), 1404-1432.

- Kulkarni, M.A., & Kothelkar, A.A. (2019). A study on best practices for employee retention and commitment. Our Heritage, 67(2), 1877–1892.

- Kurtessis, J.N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M.T., Buffardi, L.C., Stewart, K.A., & Adis, C.S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of management, 43(6), 1854-1884.

- Latimaha, R., Bahari, Z., & Ismail, N.A. (2019a). Examining the Linkages between street crime and selected state economic variables in Malaysia: A panel data analysis. Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia, 53(1), 59–72.

- Latimaha, R., Bahari, Z., & Ismail, N.A. (2019b). Examining the linkages between street crime and selected state economic variables in Malaysia: A panel data analysis. Jurnal Ekonomi Malaysia, 53, 1.

- Lent, R.W., & Brown, S.D. (2013). Understanding and facilitating career development in the 21st century. Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 2, 1–26.

- Long, C.S., Ajagbe, M.A., & Kowang, T.O. (2014). Addressing the issues on employees' turnover intention in the perspective of HRM practices in SME. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 129, 99-104.

- Mahajan, V.G. (2015). Job satisfaction and life satisfaction of high school teachers as a function of biographical characteristics.

- McElroy, J.C., & Weng, Q. (2016). The connections between careers and organizations in the new career era: Questions answered, questions raised. Journal of Career Development, 43(1), 3-10.

- Morgeson, F.P., Brannick, M.T., & Levine, E.L. (2019). Job and work analysis: Methods, research, and applications for human resource management. Sage Publications.

- Mowday, R.T., Porter, L.W., & Steers, R.M. (2013). Employee organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. Academic press.

- Nawaz, M., & Pangil, F. (2016). The relationship between human resource development factors, career growth and turnover intention: The mediating role of organizational commitment. Management Science Letters, 6(2), 157-176.

- Nawaz, M.S., Siddiqui, S.H., Rasheed, R., & Iqbal, S.M.J. (2019). Managing turnover intentions among faculty of higher education using human resource management and career growth practices. Review of Economics and Development Studies, 5(1), 109-124.

- Öncel, L. (2014). Career adapt-abilities scale: Convergent validity of subscale scores. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(1), 13–17.

- Perrone, K.M., Gordon, P.A., Fitch, J.C., & Civiletto, C.L. (2003). The adult career concerns inventory: Development of a short form. Journal of employment counseling, 40(4), 172-180.

- Piccolo, R.F., Buengeler, C., & Judge, T.A. (2018). 17 Leadership [Is] organizational citizenship behavior: Review of. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior, 297.

- Price, J.L. (2001). Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. International Journal of manpower, 22(7), 600-624.

- Rani, S., & Mishra, K. (2018). Organizational commitment issues and challenges. South Asian Journal of Marketing & Management Research, 8(7), 4–14.

- Rossi, P.H., Lipsey, M.W., & Henry, G.T. (2018). Evaluation: A systematic approach. Sage publications.

- Rubenstein, A.L., Eberly, M.B., Lee, T.W., & Mitchell, T.R. (2018). Surveying the forest: A meta‐analysis, moderator investigation, and future‐oriented discussion of the antecedents of voluntary employee turnover. Personnel Psychology, 71(1), 23-65.

- Salem, S.F., & Alanadoly, A.B. (2020). Personality traits and social media as drivers of word-of-mouth towards sustainable fashion. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management.

- Salem, S.F., & Salem, S.O. (2018). Self-identity and social identity as drivers of consumers' purchase intention towards luxury fashion goods and willingness to pay premium price. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 23(2).

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. John Wiley & Sons.

- Shrivastava, A. (2018). Effect of affective, normative and continuance commitment on organizational effectiveness. Indian Journal of Public Health Research & Development, 9(11), 1977–1986.

- Son, J., & Ok, C. (2019). Hangover follows extroverts: Extraversion as a moderator in the curvilinear relationship between newcomers' organizational tenure and job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 72-88.

- Su, C.C., & Chan, N.K. (2017). Predicting social capital on Facebook: The implications of use intensity, perceived content desirability, and Facebook-enabled communication practices. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 259-268.

- Tieger, P.D., Barron, B., & Tieger, K. (2014). Do what you are: Discover the perfect career for you through the secrets of personality type. Little, Brown Spark.

- Thevenin, S., Zufferey, N., & Potvin, J.Y. (2017). Makespan minimization for a parallel machine scheduling problem with preemption and job incompatibility. International Journal of Production Research, 55(6), 1588-1606.

- Tzabbar, D., Tzafrir, S., & Baruch, Y. (2017). A bridge over troubled water: Replication, integration and extension of the relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance using moderating meta-analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 27(1), 134-148.

- Vanhala, M., & Ritala, P. (2016). HRM practices, impersonal trust and organizational innovativeness. Journal of Managerial Psychology.

- Van Yperen, N.W., Wörtler, B., & De Jonge, K.M. (2016). Workers' intrinsic work motivation when job demands are high: The role of need for autonomy and perceived opportunity for blended working. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 179-184.

- Vinkenburg, C.J., & Weber, T. (2012). Managerial career patterns: A review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 592–607.

- Wandera, C. (2019). Internal mentorship and employee career growth in non-government organizations in Uganda. Kyambogo.

- Wayne, S.J., Shore, L.M., & Liden, R.C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management journal, 40(1), 82-111.

- Wong, C.A., & Laschinger, H.K.S. (2015). The influence of frontline manager job strain on burnout, commitment and turnover intention: A cross-sectional study. International journal of nursing studies, 52(12), 1824-1833.

- Weng, Q.X., & Hu, B. (2009). The structure of career growth and its impact on employees' turnover intention. Industrial Engineering and Management, 14(1), 14-21.

- Wong, Y.T., Wong, Y.W., & Wong, C.S. (2015). An integrative model of turnover intention: Antecedents and their effects on employee performance in Chinese joint ventures. Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 6(1), 71-90.

- Zhang, Y. (2016). A review of employee turnover influence factor and countermeasure. Journal of Human Resource and Sustainability Studies, 4(2), 85–91.