Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

Challenges Faced by the Informal Small to Medium Enterprises A Case Study of the Manufacturing Sector in Zimbabwe

Matsongoni H, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Mutambara E, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Keywords

Informal SMEs, Informal Economy, SME Development Bank, Formalize

Abstract

The study sought to establish the challenges faced by the informal manufacturing small to medium enterprises (SMEs) in Zimbabwe’s five (5) major cities of Harare, Bulawayo, Gweru, Masvingo and Mutare using primary data. The study objective was primarily to investigate the challenges faced by the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe. The survey method was used to collect data from a sample of 383 respondents. The study was limited to the informal manufacturing SMEs in six (6) categories which include food, bakery and confectionary processing, toiletry, textile and garment, leather and rubber production, engineering and metal fabrication and timber and furniture making. Research findings revealed that the informal manufacturing SMEs face limited access to finance, lack of infrastructure and collateral security, limited research, development and marketing skills, poor business structures, environment and location, lack of entrepreneurial and management skills and strict legal and regulatory framework. The study also revealed that poorly defined legal and regulatory framework negatively impact the informal SMEs economic growth and development. The study recommended that the government of Zimbabwe introduce legal and regulatory reforms to ensure that informal manufacturing SMEs can easily formalize their economic activities.

Introduction

Zimbabwe’s informal economy is growing at an alarming rate against a background of a declining formal economy (Watanga & Shilongo, 2021). At the time of conceptualizing the paper, the informal sector has gradually become the largest absorber of labour as the country faces tougher economic challenges (Dlamini & Schutte, 2020). A 2020, Labour Force Survey shows that approximately 90% of the economically active population aged 18 years and above currently work in the informal economy.

Watanga & Shilongo (2021) argue that the manufacturing sector four (4) decades post-independence was the most protected sector before the trade reforms and the adoption of Structural Adjustment Programme (SAPS). Liberalisation has had the greatest impact on the economy with the mushrooming of the informal SMEs in Zimbabwe.

Informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe are largely diversified and operate in different market conditions with varying scale of operations from one city to the other. Many of the informal SMEs engage in different manufacturing activities including but not limited only to carpentry, textiles, shoemaking, panel beating, metal fabrication and toiletry production (Bango, 1990; Chiwera, 1990).

In the period 1980 to 1990, the Zimbabwean manufacturing sector contributed 15% of formal employment and 25% towards the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, a volatile macroeconomic environment saw the performance of the sector declining by more than 50% between the year 2000 and 2008 mainly because of the influx of cheaper imported products, recurrent droughts, shortage of foreign currency, lack of adequate capital, hyperinflation, price distortions caused by government price controls, unreliable utility and energy supplies (coal, fuel, water and electricity) (WTO, 2011).

Confederation of Zimbabwe manufacturing sector survey (2017:14) asserts there was a significant decline in the number of people working in the formal sector, with the majority who lost their jobs joining the informal sector. In addition, Mumbengegwi (1993) indicated that in small urban centres of Zimbabwe the activities from the formal sector are limited or non-existent with much of the manufacturing activities occurring in the informal sector which was dominated by small to medium enterprises.

Despite the high significance and importance of the informal SMEs in African countries they still face many challenges affecting their ability to contribute to their economic successfully. The good that comes from the informal manufacturing sector in Zimbabwe should be understood to come against a background of many difficulties and challenges faced in this sector.

Aim of the Study

The aims of the study were to assess the challenges faced by the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe through a survey in which the questionnaire was used to gather data with the overall view to ensure informal sector growth and performance.

Definition of Terms

Informal SMEs

Hart (1973) used the term informal businesses to refer to a multitude of business economic activities adopted by migrant workers in Ghana in light of marginal job markets in total response to their social needs. Informal SMEs are defined as those entities whose economic activities are not included in the computation of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and not subjected to formal legal compliance (Schinder, 1998). Most informal SMEs are not licensed and do not pay taxation through their income which is normally spend in the formal economy.

Informal Economy

Economic anthropologist Keith Hart in the early 1970s on a study in Ghana observed that the informal sector had just existed but expanded. The term was popularised and gained widespread acceptance when International Labour Organisation (ILO) first used it to analyse the economic activities in Kenya in 1972 for their mission on ILO employment. ILO noted that these economic activities are unregulated, unrecognized, unrecorded and unprotected.

ILO (1999a) defines the informal economy as very small businesses that produce and distribute goods and services mainly made up of independent, self-employed manufacturer in developing countries with some employment family labour and few contract employees.

ILO (1999a) also notes that businesses in the informal economy operates with limited capital, or nothing at all; uses lower level of technology and skills and therefore operate at very low levels of production. It usually provides low and irregular income streams and an unstable and unpredictable working environment for those who work for it.

These are regarded as informal in the sense that the majority of the businesses are unregistered and unrecorded in the country’s national official statistics. The informal economy has its own controversy with some arguing that it is judgmental and gives moots the impression that those entreprenuers’ involved are very ‘irresponsible and unreliable’ (Castillo et al., 2002). Nattrass (1987), states that the informal sector is made up of entrepreneur’s who operates outside the formal wage employment in a large-scale officially recognised and regulated sector, and also includes SMEs which function outside the normal government laws, rules and regulations using labour-intensive technology.

ILO (2004), points out that economic downturns tend to be associated with the rapid growth of SMEs and economic expansion tends to be associated with low growth rate. The increase in urban informal sector is an indication of the hardships related to the adoption of the Economic Structural Adjustment Program (ESAP) and its failure to generate enough jobs. However, it is important to note that informal sector economic activities are of paramount importance to the society’s welfare. Informal SMEs contributes greatly towards the gross domestic product.

Development of Informal Manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe

The adoption of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPS) in the period 1990 to 1999 gave birth to a hostile economic environment characterised by restructuring, retrenchments, collective bargaining, high company closures, failure to pay monthly salaries by organisations and high employment. With the introduction of many black economic empowerment policies in 2009 a sudden decline in foreign direct investment was experienced and this negative impact witnessed the closure of many companies, an increase in involuntary retrenchment, an increase in unemployed economically active population. This gave rise to the mushrooming of SMEs that are unlicensed and unregistered as the unemployed people tried to eke a living from their businesses (Marunda & Marunda, 2014). These socio-economic and political landscape led to a flourishing and vibrant informal sector in Zimbabwe.

Challenges Faced by the Informal Manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe

Evidence from (Ladzani & Van Vuuren, 2002; Karedza, Sikwila Nyamazana, Mpofu & Makurumidze, 2014), have shown that, when many small businesses emerge, a considerable number of them fail because of many challenges. Research has shown that some fail at their infancy stage while the majority fails within a few years after start-up. Rao, Kumar, Gaur & Verma (2017) in a study in India observed that SME owners are faced with significant challenges, the most common being the high cost of credit, information asymmetry, creditworthiness, and complex lending procedures from financial institutions. Delmar & Wiklund (2008), also indicate that the business operating environment has a significant impact on the growth of the new small enterprises especially the informal small-to-medium enterprises. Smit, Cronje, Brevis & Vrba (2007), highlight that the business environment constitutes variables that may influence the organisation internally or externally towards its successful existence. For prosperity to be realised the investment and business environment should be attractive enough on some important variables to stimulate enough competition, investment and growth in the private sector for both the informal and formal SMEs.

Accessibility to Finance/Credit

Historically, small-to-medium enterprises have always had accessibility to loans and capital as one of their main challenges (Distinguin et al., 2016). Bolton (1971) points out that there are two main issues underlying the SMEs financing gap: this is the debt gap that relates to a lack of awareness about the suitability and appropriateness of sources, merits and demerits of finance; and secondly the supply gap that relates to the unavailability of financial resources and the higher/expensive cost of financing for small-to-medium enterprises than for large corporations or enterprises. Hussain, et al., (2006), Porumboiu (2016); Distinguin, et al., (2016) observe limited accessibility to finance is a challenge to SME development and growth irrespective of the location, size and industry or the operating environment of the market.

Cassar (2004) argues that lack of access or availability of finance is one of the challenges to SMEs’ development. Literature has shown that informal SMEs have been financed from founder’s wealth or ‘informal’ sources such as family and friends while formal SMEs have been financed from external sources of finance or the ‘formal’ market-based sources such as a bank, venture capitalists and private equity firms. Once the SMEs have been fully established, further development can be financed through the use of ploughed back/retained profits.

Herrington & Wood (2003); Herrington, Kew & Kew (2009) observe accessibility to finance is one of the major problems for African entrepreneurs. This is further observed by Stilgliz and Weiss (1981), who described the lack of finance as the ‘finance gap’ with research indicating that informal SMEs may not be able to survive and grow without addressing accessibility of finance as one of the main challenges (FinMark Trust, 2006). For example, in South Africa, an estimated 2% of new SMEs can access bank loans while 75% of applications for bank credit by new SMEs are rejected for various reasons (Foxcroft, Wood, Kew, Herrington & Segal, 2002).

Accessibility to formal finance especially among the informal SMEs is very poor because of the high risk of default among SMEs and inadequate financial facilities especially in developing countries and Africa at large. This is because of undeveloped financial markets which suffer from structural and institutional factors (Ayyagari, Beck & Demirgue-Kunt, 2003; Kauffman, 2005).

Krasniqi (2007); Abor & Quartey (2010), further lament that access to finance is a key factor governing the potential of SMEs to expand, grow and keep up to date with latest technologies. Studies by Robson & Bennett (2000); Beck (2005); Hutchison & Xavier (2006); Beck & Demirgue-Kunt (2006); Mahadea & Pillay (2008), concluded that the financing gap is one of the greatest challenges hindering SME growth, development and expansion.

Khan (2015), in a study in Pakistan, asserts that informal sources of finance have a negative impact on the small-to-medium enterprises’ growth. In support of this Namusonge (1998); Soderbaum (2001) (both cited by Migiro, 2005), in a study in Kenya, point out that a large proportion of Kenya’s manufacturing firms survive regarding retained earnings. ZEPARU & BAZ (2014), on the other hand, has reiterated that the flow of credit to the informal economy has heavy obstacles as a result of the limited information disclosed. Informal SMEs in developing countries in most cases possess adequate information about their businesses which they fail to present properly to convince the banking institutions. ZEPARU & BAZ (2014); Nyamwanza, Paketh, Makaza & Moyo (2016) conclude that limited accessibility to finance is also one of the major constraints confronting the proprietors in the informal sector in Zimbabwe.

Lack of Management and Entrepreneurial Skills

Hellriegel, et al., (2008), point out that managerial competency is very important to the survival and growth of the informal small-to-medium enterprises in many countries. Their view is supported by Martin & Staines (2008), who observes lack of management skills and experience are some of the main factors why new informal firms always fail.

According to Cronje & Smith (1992), management is the process of planning, organising, directing and controlling employees in an organisation. The informal SMEs especially most of them being sole proprietors tend to perform most if not all management tasks by himself or herself with some tasks either being underperformed or not given the attention it deserves. In that regard, strategic planning and financial management are usually sacrificed in the whole process of managing with banks and investors feeling insecure to lend and or provide their funds. Maseko & Manyani (2011), in a study in Zimbabwe, highlighted that many of the SMEs do not keep accounting records owing to a lack of proper book keeping procedures and the high cost of hiring professional accountants. This is further supported by Lutfi, Idris & Mohammed (2016) who observes that despite the vast benefits of an accounting information system, most SMEs are still lagging on its use because of the higher cost to acquire it.

Poor Location and Networking

Mario (2018:47) observes that networking is an important tool for small to medium enterprises entrepreneurs’ that allows them to grow and develop key competencies in marketing strategy through the use of the internet and individual networking by developing long-term relationships. Dahl & Sorenson (2007) argue that geographical proximity is one of the variables that forms an enhanced environmental scanning that enables new SMEs to have access to buyers and suppliers that ensures that SMEs can easily identify and exploit the growth opportunities in their market. Networking according to Okten & Osili (2004), helps new entrepreneurs to tap the means of production in the external environment successfully by ensuring reduced information asymmetry. Shane and Cable (2002) further argue that networking increases the SMEs’ legitimacy which positively influences the firm’s accessibility to external sources of financing thereby increasingly gaining competitive market.

Banwo, Du & Onokala (2017) point out that location offers mixed advantages to SMEs depending on the nature and size of the business. Many informal SMEs in Africa have a poor location and therefore this has a great impact on their market potential and growth opportunities (Olawale & Garwe, 2010). However, Ngoc, Le & Nguyen (2009) highlight that in the absence of effective market institutions; networks in developing countries play a very noteworthy role in spreading the good news and knowledge about a firm’s existence and its best practices: this suggests that networks can positively impact on the growth of the new small-to-medium enterprises. McPherson (1995) sums it all up by stating the key determinant of the informal sector survival was the factor of location, with the majority of home-based enterprises showing higher hazards and high failure rates than enterprises which were based in commercial districts. Maunganidze (2013), in a study in Zimbabwe, pointed out that designated operating spaces for the informal manufacturing SMEs are crowded with entrepreneurs’ failing to secure strategic places and, in most cases, opting to operate in undesignated placed illegally. Lee, Park, Yoon & Park (2010) however, argues that the clustered nature of small to medium enterprises creates an opportunity for economies of scale as it is expected to facilitate synergies, specialisation and cost cutting through the sharing of infrastructural facilities and supply chain management processes.

Poorly Defined Legal and Regulatory Framework

Government regulation on businesses is an important tool of concern for all economies globally (European Commission, 2010). The general belief is that regulation is a necessary evil meant to provide stable trading conditions and to develop some high degree of business trust which can create a conducive environment for SME development (Welter & Smallbone, 2006; Atherton et al., 2008). However, de Soto (1989) observes that tight regulations and high taxation levels may hinder the growth of the small informal firms, thereby contributing to high transaction costs.

Chen (2012) postulates that the legal environment frequently overlooks the broad classes of the informal sector. Bromley (2000), laments that the absence of the legal environment is as costly to the informal operators as an excessive legal environment. Many states globally tend to enforce one or two positions directed towards the informal sector economic activities in an attempt to try to remove it or turning a blind eye to it. Many of the government stances have a punishing effect like eviction, harassment and the high demand for a bribe by the relevant authorities and/or other vested stakeholders. Globally, no government have created and adopted a coherent policy or programmes towards informal sector economic activities. Rather, most government assign handlers of informal sector entrepreneurs to that department that has a mandate for legal compliance and order (Bhowmik, 2004; Mitullah, 2004).

World-wide, deregulation, over-regulation and lack of regulation are bad for the informal sector and its respective employees. There is need to rethink regulatory environments (sector specific) to determine proper regulations for the informal economy and the components of informal employment.

The World Bank (WB) (1992:30) asserted that a good legal framework for economic development has five (5) key elements:

a) There is a set of rules (governance) known in advance;

b) The rules are in force;

c) There are mechanisms ensuring application of the rules;

d) Conflicts are resolved through binding decisions of an independent judicial body

e) There are procedures for amending the rules when they no longer serve their purpose.

In summary, the best legal framework, therefore, eases economic transactions, reduces uncertainty and helps markets to realise optimal profits. This is further supported by Mutalemwa (2009), who observe the legal and regulatory framework has a very important role to play in economic growth and development of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) even though it is still weak. It is further postulated that in developing and transitioning countries especially in Africa, informal SMEs have difficulties of operating in an environment that is characterised by weak and corrupt state institutions. Most SMEs usual face high-risk environment and this tends to weaken the role of the law in coordinating and facilitating exchange (Mutalemwa, 2009).

De Soto (1989) argued that a very important key factor contributing to the increase in poverty in many developing countries is the stumbling blocks placed by governments that inhibit capitalism to flourish and by implication, the growth of SMEs. Bureaucracy and the high cost of business licensing requirements or outright corruption forces SMEs to largely operate outside the reach of their government’s facilities which limits accessibility to credit markets, accessibility to markets, infrastructure and legal institutions (Stern & Loeprick, 2007). Nyamwanza, et al., (2016) in support point out that it is difficult to secure permits and licences in Zimbabwe.

Omer, Van Burg, Peters & Visser (2015) observe that SMEs form part of the country’s economic policy and in most cases, government introduces some rules, policies and regulations applicable to both informal and formal SMEs. Mahadea & Pillay (2008), argued that these regulations can also have a constraining effect on operating of SMEs. They further concurred that state regulations and taxation laws were a significant constraint to the growth and development of the SMEs, with industrial legislation and ‘red tape’ constituting part of this negative effect.

This is further supported by several studies Kozan & Oksoy (2006); Mahadea & Pillay (2008); Olawale & Garwe (2010); Rankhumise & Rugimbana (2010); Peck, Jackson & Mulvey (2017), who identified the adverse effects of government regulations on SME growth and development. Krasniqi (2007), points out that the need for compliance with government regulations attributes to increased costs for SMEs and thus hindering the growth of SMEs. Research by McCulloch (2001), in East Africa, has shown that the private sector is over-regulated characterised by confusing and contradictory requirements which overlap and duplicate each other at central and local government levels as evidenced by uncertainty and inadequate information and costly delays in clearances and approvals. Tanzania has probably suffered the highest form of over-regulation. In 1996, a firm in the Republic of Tanzania could be expected to submit at least 89 documents for filing per year compared to 48 in Uganda, 29 in Namibia and 21 in Ghana signifying the tough regulation for Tanzania. Nuwagaba & Nzewi (2013); Altenburg, Hampel-Milagrosa & Loewe (2016) argue that the legal and regulatory environment in many developing economies is burdensome compared to developed economies and usually hinders the growth of small to medium enterprises.

Technological Capabilities

China and India recently rose to the high road of competitiveness to become the ‘Asian Drivers’ of the East Asian economies through building and continuously enhancing their technological capabilities (Goldstein, Pinaud, Reisen & Chen, 2006). Technological development is a key element in ensuring that SMEs can be able to compete in both the domestic and international markets. According to Lall (1993), technological activities should be imagined by thinking beyond the firms as a single SME does not have the necessary knowledge to introduce new products and processes thus the need to interact with home and foreign players in creating and advancing the technology being used.

A study by Levy, Berry & Nugent (1999), concluded that SMEs, formal and informal, build their technological capabilities by drawing from international exhibitions, licensing agreement or from vertical integration links as in the case of Korea and Japan respectively. African SMEs have exhibited in most cases low levels of technological efforts and linkages which have hindered these firms’ capacity in competing on the international market (McCormik et al., 1997; Levy, Berry, Itoh, Kim, Nugent & Urata 1999; Osano & Languitone, 2016). In SSA, Lall (1993); UNCTAD (2004), asserted that SMEs tend to overspend in technology acquisition and to upgrade at individual and enterprise levels by concentrating on hardware at the expense of the software.

Chidoko, et al., (2011:28); Nyamwanza, et al., (2016:304), in their studies in Zimbabwe, reiterated that lack of adequate equipment is a critical problem for many informal SMEs that do not have reliable and proper equipment to do their day-to-day work and duties. Given this limitation, governments should play a robust role in making great efforts to grow their economies through innovation, mechanising and taking part in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Government Policy towards SMEs

Charoensukmongkol (2016) in a study in Thailand observes that government support is a critical to the international performance of SMEs. In addition, GATT (2012), states that government’s policy towards SMEs is considered one of the important variables taken into consideration when looking at the possibility of unlocking the informal SMEs’ potential. Literature shows that government support differs significantly across the different continents with some governments creating many barriers to SME development in the form of excessive regulation and red tape. Charoensukmongkol (2016) concludes that government support in Thailand was strongly linked to the political networks that owners would have developed and the extent of bribery that they have engaged in.

In Africa, according to the World Bank Doing Business Report (WBDBR) (2012), Chad was named as the most difficult Sub-Saharan African country to conduct business, with a very high tax rate of 65%, and insolvency regulations that demand 60% of the estate value and takes long processing times. Business Regulation in Chad makes it difficult for small to medium enterprises to operate and be profitable. Nigeria is ranked number 133rd according to WBDBR (2012), because of high levels of corruption, unreliable electricity and poor infrastructure despite the implementation of a Small and Medium Enterprises Equity Investment Scheme (SMEEIS) in 1999, which encouraged a more productive small-to-medium enterprises sector. The SMEEIS was poorly implemented resulting in its objectives not being met.

Even though government support is limited in many African countries, this has not stopped the informal SMEs from growing with many entrepreneurs’ creating new opportunities in spite of the tough and difficult regulatory environment, especially in Zimbabwe (Nyamwanza et al., 2016). In support of this the African Development Bank (AfDB) (2012), reported that only 20% of African SMEs had access to credit and that about 9% of the investments SMEs made are financed through formal banking institution(s). This is in contrast to South America and the Caribbean where 44% of SMEs have had access to credit and Europe where 23% of all the SME investments are funded through formally registered banks.

Globally, many states and governments have established agencies and institutions in an attempt to support and try to assist SMEs with the overall aim being to create an enabling and conducive environment for SME development (Naicker, 2006, Mahembe et al., 2011). Tunde (2016); Osano & Languitone (2016) observe that government should provide world-class technology and research infrastructure outputs through government owned institutions to produce highly skilled workforce and an entrepreneurial culture of SMEs. State should provide concessionary lending interest rates for new technologies acquisition and provide taxation incentives for the small to medium enterprises procuring new technologies. A good relationship between state agencies and institutions is a positive step towards developing an environment within which SMEs can unlock their potential and discover new opportunities and growth (Studer et al., 2006). The absence of a conducive and supportive government can have a direct impact on SME growth and constitute a major constraint (Madrid-Guijarro et al., 2009).

Studer, et al., (2006); Mutula & Brakel (2006); Madrid-Guijarro et al., (2009), Okpara (2011), and Peters and Naicker (2013) argued that underdeveloped, undeveloped and many failed small-to-medium enterprises are as a result of minimum government support which hinders its growth and development.

Research Design and Methodology

The survey strategy was applied to carry-out an analysis of the challenges faced by the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe’s five (5) major cities.

Sampling Strategy

This study used proportionate stratified random sampling based on the information from the database of the informal SMEs provided by the Ministry of Small-to-Medium Enterprises and Cooperative Development and confirmed by ZIMSTATS (2014). This method involves using a fraction in each of the strata that are proportional to that of the total population (Kothari, 2011). This study developed these strata based on geographical location, i.e., the provincial capital cities of Zimbabwe which are Harare, Bulawayo, Mutare, Gweru and Masvingo.

The use of proportionate stratified random sampling ensured that at least one observation was picked from each of the strata and allows for the maximum understanding of the underlying phenomenon of interest (Kothari, 2011; Kardejejezska, Tadros & Baxter, 2012). Proportionate stratified random sampling was used to solicit the responses from the three hundred and eight three (383) informal manufacturing small-to-medium enterprises in Harare, Bulawayo, Gweru, Masvingo & Mutare.

Sample Size

The sample size used for the five (5) towns were 383 and the number of questionnaires anticipated to be collected were as follows:- Harare 103, Bulawayo 35, Gweru 62, Masvingo 87 and Mutare 96 respectively. The sample size of 383 was determined through calculation with a confidence level of 95% and Margin of Error of 5% (Cochran, 1977; Sekaran & Bougie, 2013).

Discussion and Results

The discussion of results focuses on access to finance, infrastructure and collateral security, research development and marketing, business structure and environmental location, entrepreneurial and managerial skills as well as legal and regulatory framework as main challenges facing the Zimbabwean informal sector. Data was analyzed using one-sample statistics and one sample t-tests.

Access to Finance

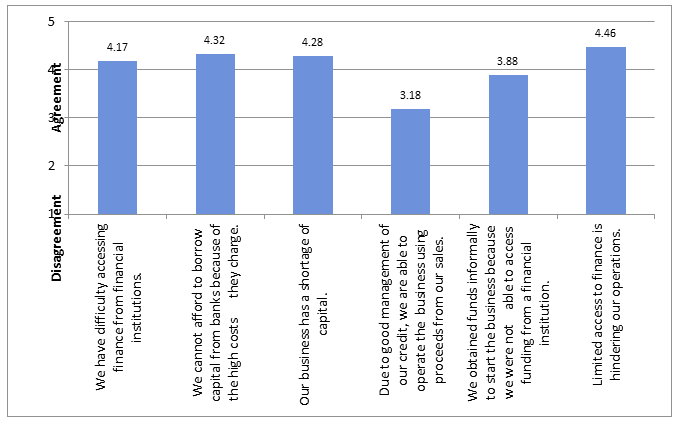

Sample participants were given a list of six (6) statements as issues that prevented informal manufacturing SMEs in achieving their success and growth regarding access to finance. The actions were scored on a Likert-scale of between 1 and 5. A score of 1 indicated strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 neutral, 4 agree while 5 indicated strongly agree. The results from the study are presented in Figure 1.

Results reveal that there is significant agreement that there is difficulty in accessing finance from financial institutions (M=4.17, SD=1.116, t(822)=30.051, p<0.0005); they cannot afford to borrow capital from banks because of the high costs they charge (M=4.32, SD=0.881, t(822)=43.032, p<0.0005); business has a shortage of capital (M=4.28, SD=0.978, t(822)=37.568, p<0.0005); good management of credit enables to operate the business using proceeds from our sales (M=3.18, SD=1.023, t(822)=5.007, p<0.0005); they obtained funds informally to start the business because they were not able to access funding from a financial institution (M=3.88, SD=1.097, t(822)=23.106, p<0.0005) and limited access to finance is hindering operations (M=4.46, SD=0.853, t(822)=49.218, p<0.0005). A similar study by Ogot (2014:127), reveals that lack of adequate capital is one of the top three challenges and remains a significant challenge despite government establishment of several funds over the last ten (10) years meant to improve the accessibility of capital to micro and small enterprises (MSEs). Ndiweni, Mashonganyika, Ncube and Dube (2014:5), also highlight that there is limited capital to expand or expand the businesses. This is further supported by Kauffmann (2005:1), who asserts that SME development in Africa is limited by limited accessibility to finance. RBZ (2014:12) points out that most SMEs lacks the capital to ensure that they can grow and increase their profitability.

Infrastructure and Collateral Security

Sample participant were given a list of eight (8) statements on infrastructure and collateral security issues facing the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe. The actions were scored on a Likert scale of between 1 and 5. A score of 1 indicated strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 neutral, 4 agree while 5 indicated strongly agree. The sample results from the study are presented in vv.

There is significant agreement that the organisation lacks modern equipment for manufacturing (M=4.11, SD=1.014, t(822)=31.425, p<0.0005); expansion is limited because of inaccessibility to land (M=3.78, SD, 0.841, t(822)=26.560, p<0.0005); limited access to water and electricity is hindering growth (M=3.72, SD=0.975, t(822)=21.099, p<0.0005); they do not have access to adequate current technology (M=3.81, SD=1.092, t(822)=21.328, p<0.0005); they are facing challenges due to lack of collateral security (M=4.17, SD=0.952, t(822)=35.101, p<0.0005); high rent is limiting expansion drive in other areas, towns and regions (M=3.89, SD=0.928, t(822)=27.648, p<0.0005) and they experience losses (pilferage) at our their premises because of poor infrastructure and systems(M=3.27, SD=1.020, t(822)=7.486, p<0.0005). Chidoko et al. (2011: 27) in a similar study in Zimbabwe concluded, that limited access to capital and collateral is one major challenge being faced by SMEs in the informal sector because of lack of collateral to secure loans. There is little or no assistance for the informal SMEs resulting in many operating below the full capacity. ZEPARU (2014) points out that there is limited accessibility to proper tools and equipment for improving productivity owing to limited accessibility to finance.

There is significant disagreement that delivery of raw materials is hindered by poor infrastructure (M=2.87, SD=1.098, t(822)=-3.271, p>0.0005.)

Research, Development and Marketing Skills

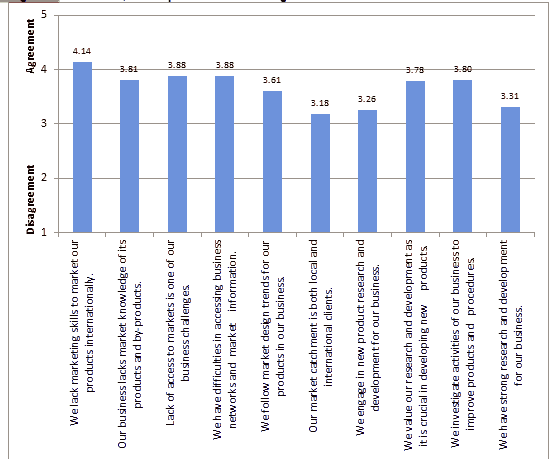

Sample respondents were given a list of ten (10) statements on research, development and marketing skills. The actions were scored on a Likert-scale of between 1 and 5. A score of 1 indicated strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 neutral, 4 agree while 5 indicated strongly agree. The results from the study are presented in Figure 3 below.

There is significant agreement that informal manufacturing SMEs lack marketing skills to market products internationally (M=4.14, SD=1.025, t(822)=31.912, p<0.0005); that business lacks market knowledge of its products and by-products (M=3.81, SD=0.958, t(822)=24.162, p<0.0005); the lack of access to markets is one of the business challenges (M=3.88, SD=0.858, t(822)=29.484, p<0.0005); they have difficulties in accessing business networks and market information (M=3.88, SD=0.788, t(822)=32.147, p<0.0005); they follow market design trends for our products in business (M=3.61, SD=0.904, t(822)=19.356, p<0.0005); market catchment is both local and international clients (M=3.18, SD=1.123, t(822)=4.656, p<0.0005), they engage in new product research and development for business (M=3.26, SD=1.280, t(822)=5.720, p<0.0005); they value research and development as it is crucial in developing new products (M=3.78, SD=0.842, t(822)=26.623, p<0.0005); they investigate activities of the business to improve products and procedures (M=3.80, SD=0.827, t(822)=27.741, p<0.0005) and they have a strong research and development for business (M=3.31, SD=1.094, t(822)=8.223, p<0.0005). Chidoko, et al., (2011: 27), in a similar study, concluded that most informal business owners lack the relevant skills to run their business, with the majority failing to keep proper accounting records. Furthermore, RBZ (2014), observes many SMEs lacks the required skills and current technology to ensure production of high-quality products and services. A study by Chimuka & Mandipaka (2015:313) reveals that SMMEs lacks marketing and networking skills, where they can share ideas on how to successfully run, grow and sustain their businesses.

Business Structures, Environment and Location

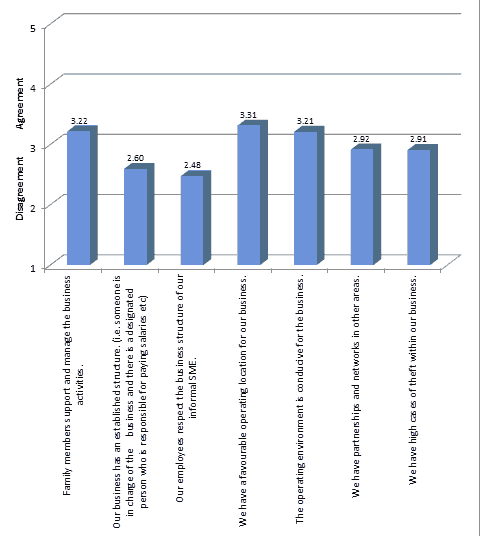

Sample respondents were given a list of seven (7) statements on business, structures, environment and location for the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe. The actions were scored on a Likert-scale of between 1 and 5. A score of 1 indicated strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 neutral, 4 agree while 5 indicated strongly agree. The results from the study are presented in Figure 4.

There is significant agreement that family members support and manage the business activities (M=3.22, SD=1.466, t(822)=4.303, p<0.0005); they have a favourable operating location for business (M=3.31, SD=1.118, t(822)=43.032, p<0.0005); business has a shortage of capital (M=4.28, SD=0.978, t(822)=8.045, p<0.0005); and the operating environment is conducive for the business (M=3.21, SD=0.989, t(822)=6.169, p<0.0005). Olawale & Garwe (2010:731), in a similar study, notes that geographical location has an advantage to buyers or suppliers since it creates a form of enhanced environmental scanning that ensures that new SMEs are easily identifiable thereby exploiting the growth opportunities in the market.

On the other hand, there is significant disagreement that the business has an established structure (M=2.60, SD=1.371, t(822)=-8.438, p<0.0005); employees respect the business structure of the informal SME (M=2.48, SD=1.329, t(822)=-11.333, p<0.0005); they have partnerships and networks in other areas (M=2.92, SD=1.028, t(822)=-2.306, p= 0.021); and they have high cases of theft within the business (M=2.91, SD=1.110, t(822)=-2.356, p=0.019).

MoSMECD (2015:11), points out that some of the challenges faced by the informal SMEs are limited workspace and poor infrastructure, limited access to modern technology for production and communication purposes, limited research and development and information sharing in the sectors, poor management and entrepreneurship skills, limited access to markets, limited access to finance and high levels of informality among many others.

Entrepreneurial and Managerial Skills

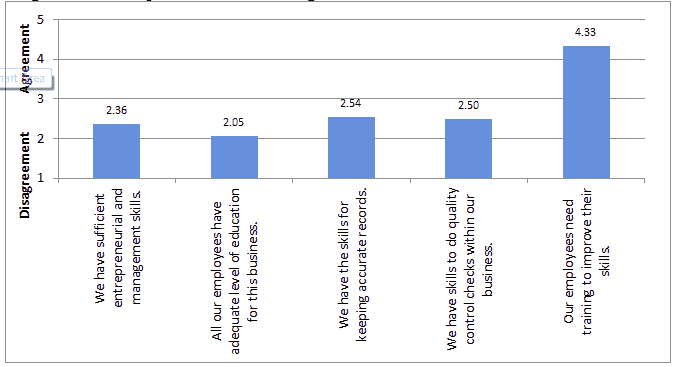

Sample participants were given a list of five (5) statements on entrepreneurial and management skills for the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe. The actions were scored on a Likert-scale of between 1 and 5. A score of 1 indicated strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 neutral, 4 agree while 5 indicated strongly agree. The sample results from the study are presented in Figure 5.

There is significant agreement that employees need training to improve their skills (M=4.33, SD=1.125, t(822)=33.958, p<0.0005). On the other hand there is significant disagreement that the business has sufficient entrepreneurial and management skill (M=2.36, SD=1.325, t(822)=-13.807, p<0.0005); all the employees have adequate level of education (M=2.05, SD=1.237, t(822)=-21.917, p<0.0005); they have the skills for keeping accurate records (M=2.54, SD1.028, t(822)=-10.055, p<0.0005); and they have skills to do quality control checks within the business (M=2.50, SD=1.416, t(822)=-10.119, p<0.0005). RBZ (2014:12), points out that that many SMEs lacks the skills and managerial capacity to run their businesses.

Uzhenyu (2014), in a similar study also highlights that there is limited business acumen in the informal sector. Many informal SMEs have no proper training for administration, leadership and management with budgets being done outside the tradition budgeting best practices. In support of above sample findings Nyanga, Zirima, Mupani, Chifamba & Mashavira (2013:146), highlights that inadequate management is one of the major challenges of SMEs and that this problem broadly includes lack or limited management skills, poor planning and experience, and inadequate business knowledge. Smit & Watkins (2012:6326), laments that a lack of management skills and training is also an important reason for the high failure rate of SMEs.

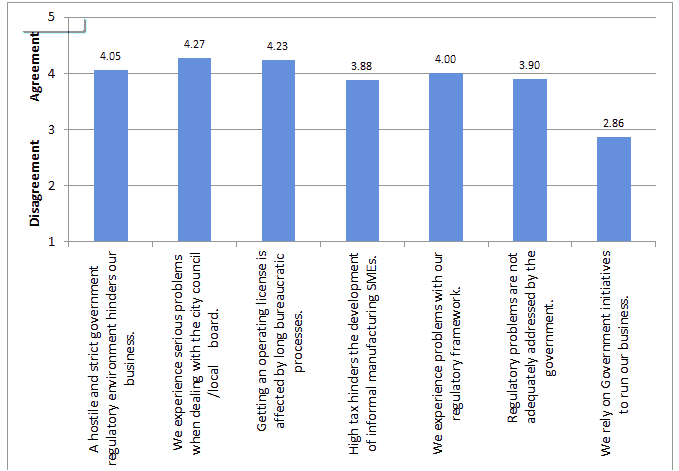

Legal and Regulatory Framework

Respondents were given a list of seven (7) statements on legal and regulatory framework issues facing the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe. The actions were scored on a Likert-scale of between 1 and 5. A score of 1 indicated strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 neutral, 4 agree while 5 indicated strongly agree. The results from the study are presented in Figure 6.

There is significant agreement that a hostile and strict government regulatory environment hinders business (M=4.05, SD=1.255, t(822)=24.110, p<0.0005); they experience serious problems when dealing with the city council/local board (M=4.27, SD=0.928, t(822)=39.271, p<0.0005); getting an operating license is affected by long bureaucratic process (M=4.23, SD=0.907, t(822)=39.061, p<0.0005); high tax hinders the development of the business (M=3.88, SD=1.041, t(822)=24.343, p<0.0005); they experience problems with regulatory framework (M=4.00, SD=0.889, t(822)=32.261, p<0.0005); and regulatory problems are not adequately addressed by the government (M=3.90, SD=1.249, t(822)=20.632, p<0.0005). In support of this sample finding, Msipah, Muchineripi, Jengeta, Mufudza & Nhemachena (2013:85), in their study highlights that the bureaucratic system in Zimbabwe has been a major limiting factor in the development of the SME sector.

On the other hand, there is significant disagreement that they rely on government initiatives to run the business (M=2.86, SD=1.216, t(822)=-3.239, p= 0.001). Akinboade (2014: 605), on a similar study based in Cameroon, concluded that regulatory compliance in Cameroon is very low citing the high cost of complying as the main challenge in ensuring compliance, since the total registration costs impacts negatively on business profitability and growth.

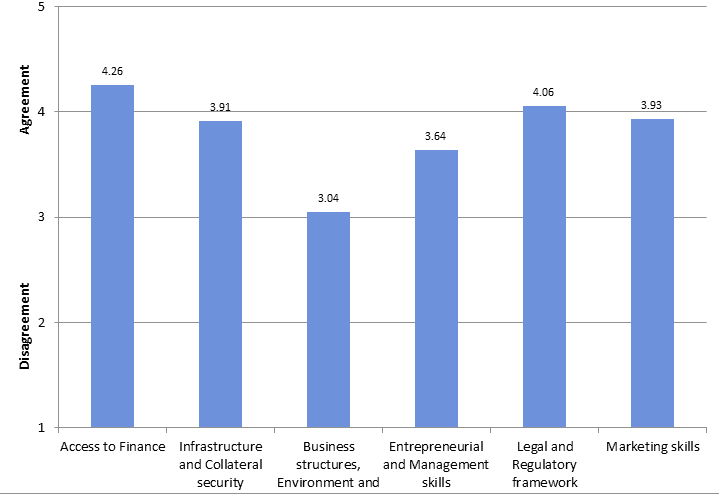

Summary of SME Challanges

The t-tests were used to ascertain the significant agreement/disagreement that these issues were challenges. The mean scores are then used to compare the extent of the challenges across the construct. The six (6) single measures: access to finance, infrastructure and collateral security, research, development and marketing skills, business structures, environment and location, entrepreneurial and management skills, legal and regulatory framework were analysed with the t-test to show the relative ‘size’ of the challenges faced by the informal manufacturing SMEs. The results of the study are presented in Figure 7, Table 1 and Table 2.

| Table 1 One- Sample Statistics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std deviation | |

| ACESS_FINANCE | 823 | 4.2568 | 0.826 |

| ICS | 823 | 3.9129 | 0.57 |

| BSEL | 823 | 3.0441 | 0.754 |

| EMS | 823 | 3.6361 | 1.08 |

| LRF | 823 | 4.0569 | 0.669 |

| MS | 823 | 3.928 | 0.621 |

| Table 2 One-Sample Test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Test Value=3 | |||

| T | Df | Sig. (2-tailed) | |

| ACCESS_FINANCE | 43.64 | 822 | 0 |

| ICS | 45.921 | 822 | 0 |

| BSEL | 1.68 | 822 | 0.093 |

| EMS | 16.887 | 822 | 0 |

| LRF | 45.358 | 822 | 0 |

| MS | 42.901 | 822 | 0 |

There is significant agreement that the greatest challenge is access to finance (M=4.2568, SD=0.82617, t(822)=43.640, p<0.0005); then legal and regulatory framework (M=4.0569, SD=0.66847, t(822)=45.358, p<0.0005); followed by research, development and marketing skills (M=3.9280, SD=0.62056, t(822)=42.901, p<0.0005); then infrastructure and collateral security (M=3.9129, SD=0.57032, t(822) =45.921, p<0.0005); entrepreneurial and management skills (M=3.6361, SD=1.08062, t(822)=16.887, p<0.0005); and the least challenge being business structures, environment and location (M=3.0441, SD=0.75375, t(822)=1.680, p= 0.093).

Conclusions and Recommendations

Zimbabwean informal manufacturing SMEs are faced with many different problems. These challenges can be broadly categorized into financial and non-financial difficulties. The challenges identified in this study are limited access to finance, legal and regulatory framework, research, development and marketing skills, entrepreneurial and management skills, and the least is business structures, environment and location. Historically and to date these difficulties have hindered the growth and development of the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe

The recommendations made to manage the challenges faced by the informal manufacturing SMEs in Zimbabwe are improved access to finance, markets, infrastructure, information/networking, technology for all the SMEs in Zimbabwe’s five (5) major cities. The Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises and Cooperative Development should not shoulder the problems of informal manufacturing SMEs alone but adopt an integrated approach involving all the concerned stakeholders. SMEs policies should be developed at central government and then be decentralised to local levels to arrest some of the challenges faced by the informal manufacturing SMEs. In addition, the Ministry of Small to Medium Enterprises and Cooperative Development should introduce legal and regulatory reforms and also as well as programmes that support the informal manufacturing SMEs.

References

- Akinboade, O.A. (2014). Regulation, SMEs growth and performance in cameroon’s central and littoral provinces’ manufacturing and retail sectors. African Development Review, 26(4), 597-609.

- Bango, S. (1990). Case study of sedco zimbabwe. Paper prepared for small scale enterprises policy seminar, nyanga: ITDG.

- Castillo, G., Frohlich, M., & Orsatti, A. (2002). Union education for informal workers in Latin America. In ILO (2002), Publication.

- Chen, M.A. (2012). The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies, women in informal employment globalising and organising (WIEGO) Working Paper No. 1.

- Chidoko, C., Makuyana, G., Matungamire, P., & Bemani, J. (2011), Impact of the informal sector on the current zimbabwe economic environment. Economic Research, 2(6), 26-28.

- Chimuka, T., & Mandipaka, F. (2015). Challenges faced by small medium and micro enterprises in the nkonkobe municipality. Business and Economic Research, 14(2), 309-315.

- Chiwera, T.A. (1990). Industrial development in Chitungwiza: Problems and prospects. Department of Rural Urban Planning, University of Zimbabwe

- Cochran, W.G. (1977). Sampling techniques. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 3.

- Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries (CZI). (2017). The State of Zimbabwe’s Manufacturing Sector

- Dlamini, B., & Danie S.P. (2020). An overview of the historical development of small and medium enterprises in Zimbabwe, Small Enterprise Research, 27(3). 306-322.

- Germini. (1993). Changes in the small-scale enterprises sector from 1991 to 1993: Results of a Second Nationwide Survey in Zimbabwe.

- Hart, K. (1973). Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. Modern African Studies, 11(1), 61-89.

- International Labour Organisation [ILO]. (1999a). Trade Unions and the Informal Sector: Towards a Comprehensive Strategy. International Symposium on Trade Unions and the Informal Sector Background Paper, Bureau for Workers’ Activities, ILO, Geneva, 18-22 October.

- ILO. (2004). Giving voice to the unprotected workers in the informal economy in Africa: The Case of Zimbabwe. Discussion Paper No.22.

- Imani Development. (1990). Implementers confronting the informal sector in Zimbabwe. Prepared for the World Bank: Zimbabwe.

- Kardzejewska, R., Tudros, R., & Baxter, D. (2012). A descriptive study on the barriers to implementation of the NSW (Australia) Healthy Schools Canteen. Health Education, 1-10.

- Kauffman, C. (2005). Financing SMEs in Africa, OECD Development Centre. Policy insights No. 7. A Joint Publication of the African Development Bank and the OECD Development Centre.

- Kothari, C.R. (2011). Research Methodology, Methods and Techniques, New Age International Publishers. 2.

- Marunda, E., & Marunda, E. (2014). Enhancing the micro and small to medium size enterprises operating environment in Zimbabwe. Business and Management, 16(11), 113-116.

- Mepherson, M. (1998). Zimbabwe: A nationwide survey of micro and small enterprises: US Agency for International Development.

- Ministry of Small and Medium Enterprises and Cooperative Development (MoSMECD) (2015). National Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Policy Framework.

- Msipah, N., Muchineripi, D., Jengeta, M., Mufudza, T., & Nhemachena, B. (2013). Entrepreneurial training needs analysis in small-scale artisanal engineering businesses in Zimbabwe: A case study of mashonaland west province. Sustainable Development in Africa, 15(2), 81-97

- Mumbengegwi, C. (1993). Structural adjustment and small scale enterprise development in Zimbabwe. Small Enterprise and Changing Policies: IT Publications

- Nattrass, N. (1987). Street trading in Transkei: A struggle against poverty and persecution. World Development, 15(7), 861-875.

- Ndiweni, E., & Verhoeven, H.A.L. (2013). The rise of informal entrepreneurship in Zimbabwe: Evidence of economic growth or failure of economic policies. Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 2(3), 260-276.

- Nyanga, T., Zirima, H., Mupani, H., Chifamba, E., & Mashavira, N. (2013). Survival of the vulnerable: Strategies employed by small to medium enterprises in Zimbabwe to survive an economic crisis. Sustainable Development in Africa, 15(6), 142-152.

- Ogot, M. (2014). Evidence on challenges faced by manufacturing informal sector micro-enterprises in nairobi and their relationship with strategic choice. Business Research, 7(6).

- Olawale, F., & Garwe, D. (2010). Obstacles to the growth of new SMEs in South Africa. A principal component analysis approach, Business Management, 4(5), 729-738.

- Remenyi & Bannister, F. (2001). Electronic Journal of Business Methods.

- Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe. (2014). Role of the banking sector in promoting growth and development of small and medium enterprises. At the 2nd SME Banking and Microfinance Summit.

- Sekeran, U., & Bougie, R. (2013). Research methods for business, a skill-building approach, (6th Edition). John Wiley and Sons Limited.

- Shinder, L. (1998). Monthly labour review. March 1998, International Report.

- Tekere, M. (2001). Trade liberalisation under structural economic adjustment – Impact on social welfare in Zimbabwe, Poverty Reduction Forum (PRF). Structural Adjustment Program Review Initiative (SAPRI).

- Uzhenyu, D. (2014). Formalising/Upgrading the informal economy: Reflections on the State of Play: A Case Study of the Capital City, Harare, Zimbabwe. Sub-Theme: Informal Employment, Impact, Challenges, Structures and Models, 7th Congress for Africa –ILERA, 15-16 September, Grand Palm Hotel, Botswana.

- Watambwa, L., & Shilongo, D. (2021), Analysis of the impact of SME financing on economic growth in Zimbabwe (2015-2019).

- World Trade Organisation (WTO). (2011). Small business Report. World Trade Organisation, Washington DC.

- Zimbabwe Economic Policy Analysis and Research Unit [ZEPARU] and Bankers Association of Zimbabwe [BAZ] (2014). Harnessing resources from the informal sector for economic development, October 2014.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency [ZIMSTATS] (2014). Survey on labour force report.