Case Reports: 2019 Vol: 25 Issue: 1

Channel Stuffing or Sales With a Right to Return?

Wayne Prem, Towson University

Arundhati Rao, Towson University

Charles Martin, Towson University

Case Description

In this case study we present the problems created by misinterpretation of Accounting Standards by a company and the independent auditor’s failure to identity and report these problems. The company, Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation (Medicis), made several mistakes in the revenue recognition process as it relates to Sales with a Right to Return. Ernst & Young, their auditor for over two decades, did not exercise professional skepticism in conducting the audits and thus failed in their duty to ensure that investors receive reliable information. This eventually led to litigation with heavy penalties for the company and its auditors. The primary objective of this case understands the complexities of an audit engagement and the role and responsibilities of the auditor. This case is designed for a (second) undergraduate or a master’s level auditing course with a difficulty rating of 3. The case may be assigned as a homework assignment or in class discussion in small groups towards the end of the semester.

Case Synopsis

Medici’s manufactured and sold pharmaceutical skin care products to wholesalers and retail chains. While the products were good, the company’s sales practices were aggressive. The company offered a very generous return policy that should have alerted the auditors that the accounting revenue recognition standards may be misinterpreted. Initially both the company and their auditor got a pass as their return policies were common practice in the pharmaceutical industry. However a second class-action lawsuit and oversight of PCAOB punished the company and their auditors with fines and penalties. This is a cautionary tale for companies that try to recognize questionable revenues.

Company History

Medici’s was founded in 1987 by Johan Shacknai (Bloomberg News, supra). Registered in Delaware, the company’s principal offices were in Scottsdale Arizona and traded on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) from 2005 through 2012 under the ticker symbol MRX. (Bloomberg News, 2015). For more than 20 years, Medici’s audits of financial statements were conducted by Ernst & Young, a Big 4 accounting firm (PCAOB News Release, 2012). Medici’s developed and sold time-dated pharmaceutical products, such as Solodyn & Ziana, acne prevention drugs, primarily to wholesale distributors and retail chain drugstores (collectively, the“customers”) (Ibid). Management practice of channel-stuffing and misinterpretation of revenue recognition standards led to misstatement of financial statements over a six-year period resulting in litigations and penalties.

In 2012, Valeant Pharmaceutical International, a Canadian drug maker, acquired Medicis for $2.6 billion (Ibid). One of the terms of the merger was that Medicis would delist its stock from the NYSE but continue to operate as a subsidiary of Valeant Pharmaceuticals International which traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol VRX. Johan Shachnai continued as the CEO of the subsidiary company. In July 2018, the company changed its name to Bausch Health Companies Inc. and is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol BHC.

Accounting Mistakes

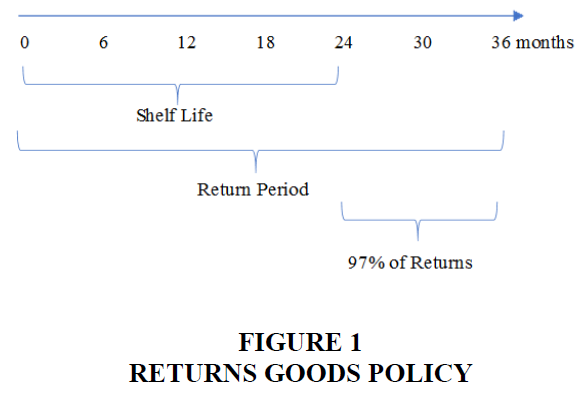

Medici’s developed and sold time-dated pharmaceutical products, such as Solodyn and Ziana, acne prevention drugs, primarily to wholesale distributors and retail chain drugstores. The company’s“returns goods policy” gave the customers the right to return the product if the product was returned within 4-6 months before expiration or up to 12 months after expiration (collectively, the“expired product”). Most of its products had a shelf life of 18-24 months. According to the“Returns Goods Policy,” upon return of the product, customers received full credit in the amount of the original purchase price or pricing one year prior to the date Medicis receives the return. The policy did not require the customer to purchase the same or similar product to receive or use the credit for returning the expired product. Customers would, however, routinely purchase the same product within the same quarter in which the return credit was issued. Medici’s“Returns Goods Policy” (Figure 1) did not distinguish between returns replaced in the quarter and returns not replaced in the quarter (PCAOB, 2012).

At the time of sale, Medicis would record product revenue and estimate future product returns, reducing revenue in its financial statements. Although not set forth in its returns policy, the estimated reserve was calculated at replacement cost for the expired product, even though the customer receives full credit in the amount of the gross sales price for the product returns, regardless of when the customers used their credit to buy a“replacement product.” During the 2006 audit, it was determined that 97% of all sales returns were for expired products and that 72% of all expired products returned were replaced in the same quarter. By estimating the returns reserve at replacement cost, rather than gross sales price, Medicis reported an 85% gross margin at the time of sale, even though it issued a credit for the gross sales price, when the product was eventually returned. This method had a material impact on Medici’s returns reserve estimate, resulting in approximately a $54 million difference in the reserve estimate (PCAOB, supra).

Beginning in 2006, Medicis applied a different reserve methodology that relied upon significant assumptions that were inconsistent with historical return patterns. The reserve amount was determined by the launch date of the product sold to its customers. If the product was launched within the last 4 years, it was referred to as a“non-legacy product.” If the product was launched more than 4 years before sale, those products were referred to as“legacy products.” The estimated reserve amount for sales returns of non-legacy products was based on estimating the total units of inventory in the distribution and retail channels and comparing that total estimate to an estimate of the units of inventory in the channels that would not be returned for expiry due to product demand (the“units-in channel methodology”). The estimated reserve amount for sales returns of legacy products was the same method utilized by Medicis in 2005, based upon replacement cost determined by historical return rates (PCAOB, supra).

Audit Failures

Ernst & Young was Medici’s auditors for more than twenty years. Assigned to the audit of the Medici’s financial statements for the 6-months ended December 31, 2005 was Jeffrey S. Anderson, the supervising senior auditor and Robert H. Thibalt, the independent review partner (PCAOB, supra). Despite having questioned Medici’s accounting policy of using replacement cost to estimate the year-end sales returns reserve, neither Anderson nor Thibalt objected to this practice. Rather than relying on SFAS 48 Revenue Recognition When A Right of Return Exists, the auditors believed that Medicis had a right to use replacement cost in estimated the reserve for sales returns under SFAS 5 Contingencies. (PCAOB, supra). Ernst & Young’s audit team, led by Anderson, mistakenly analogized the use of replacement cost to a warranty exception. The auditors believed that, since the final customer was exchanging a product for a similar product, the reserve may be booked at replacement cost rather than at the gross sales price. This created a twofold problem:

1. The final customer was not returning the item.

2. The exchange was not for a same type of product.

Medici’s customers were resellers, either wholesalers or retail outlets, not the ultimate consumer. The product being returned was expired and the product reissued was a freshly-dated product. The situation is not an exchange contemplated by SFAS 5, wherein the ultimate consumer returns to the store to exchange a blue shirt for a green shirt or a large sized shirt for a medium-sized shirt (PCAOB, supra).

Furthermore, less than two months after concurring with Medici’s use of the so-called“exchange exception” to SFAS 48, Ernst & Young’s Audit Review Quality team questioned Medici’s accounting rationale but ultimately permitted Medicis to utilize replacement cost to estimate its sales returns reserve (PCAOB, supra). This decision was later criticized in 2011 by the PCAOB inspection of the audit. PCAOB Chairman, James R. Doty stated:“[Ernst & Young] failed to fulfill their bedrock responsibility. The auditor’s job is to exercise professional skepticism in evaluating a public company’s accounting and in conducting its audit to ensure that investors receive reliable information, which did not happen [in this audit]” (PCAOB News Release, 2012).

Medicis And Ernst & Young Dodge The First Bullet

On October 3, 2011, shareholders instituted a class action lawsuit in the United States District Court for the District of Arizona against Medicis, Johan Shacknai, Medici’s founder and Chief Executive Officer, Richard Peterson, Medici’s Chief Financial Officer, Mark Prygocki, Medici’s Chief Operating Officer and Ernst & Young (In Re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp, 2011). In the lawsuit, Medicis was alleged to have violated SFAS 48 which stated that revenue may be recognized on product sales when a right of return exists, but only if certain conditions are satisfied:

1. The returns can be reasonably estimated.

2. A reserve account for estimated future returns based on the gross sales price of returned products is maintained.

Over a six-year period, 2002 through 2007, the restated financial statements filed by Medicis resulted in an understatement of net income of approximately $1.1 million (Table 1).

| Table 1: Six Year Financial Statement (2002-2007) | ||

| Time duration | Income | Result |

| Year-ended June 30, 2003 | 37.2 m | Net Income Overstatement |

| Year-ended June 30, 2004 | 11.5 m | Net Income Understatement |

| 6 month ended June 30, 2005 | 11.2 m | Net Income Overstatement |

| 6 month ended December 31, 2005 | 1.3 m | Net Income Understatement |

| Year-ended December 31, 2006 | 44.0 m | Net Income Understatement |

| Year-ended December 31, 2007 | 7.3 m | Net Income Overstatement |

| Six-Year Period | $1.1 m | Net Income Understated |

Medici’s argued that its violation of SFAS 48 was a misinterpretation of a“technical” accounting provision. The shareholders alleged the violation was intentional or with deliberate recklessness and resulted in a manipulation of revenues by management. By“stuffing the distribution channel” with its products that it knew would be returned, Medicis was booking revenues years in advance by“omitting the required reserve and concealing from investors the fact that a material portion of the sales were likely to be returned.” Whistleblowers came forth to testify that Medici’s sales returns reserve estimations were“deceptively low and/or were using an inapplicable GAAP exception” (Ibid).

Despite whistleblower evidence from seven witnesses (Edwards, 2011), Judge G. Murray Snow dismissed the action (In Re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp., supra). Judge Snow found that the shareholders did not satisfy the burden of proving, pursuant to Rule 10b-5 of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 and the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act that the defendants acted with scienter (i.e. intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud). Scienter“must [be] state[d] with particularity [of the] the circumstances constituting the fraud or mistake” and requires a strong inference that a defendant acted with the required state of mind to commit intentional acts of fraud or acted with“deliberate recklessness” that amounts to fraud (Ibid). Judge Snow stated that the plaintiffs failed“to allege an accounting error that was so obvious that the defendants must have been aware that their interpretation of SFAS 48 was incorrect” (Ibid). Accounting literature did not make Medici’s error obvious. A statement of position relating to another industry, such as the software industry, was rejected by the Court as authoritative literature. The Court went further to acknowledge that“other pharmaceutical companies have attested to the SEC that they too allowed exchanges of expired product for fresh product and then booked revenues using replacement cost” (Ibid). Judge Snow stated that a restatement or an accounting error does not give rise to scienter (Ibid). In his concluding remarks, Judge Snow stated:“even when viewed holistically, the amended complaint does not give rise to a strong inference of scienter with respect to any of the defendants” (Ibid).

Ernst & Young Is Hit By A Second Bullet

On February 8, 2012, the PCAOB brought disciplinary proceedings against Ernst & Young and its individual auditors, Anderson, Thibalt, Ronald Butler, Jr., the second partner in the audit of the December 31, 2005 financial statements and Thomas A. Christie, the second partner in the audit of the financial statements for the year-ended December 31, 2007, for violations of the PCAOB standards of auditing (PCAOB, supra). The PCAOB assessed a $2 million civil penalty against Ernst & Young, the largest civil penalty issued by the PCAOB at the time. PCAOB’s Division of Registration and Inspections concluded that Ernst & Young’s acceptance of Medici’s accounting for its sales returns reserve violated PCAOB standards since the accounting did not comply with GAAP (Ibid). The PCAOB Director also found that in auditing Medici’s new methodology, Ernst & Young failed to sufficiently audit key assumptions and placed reliance on management’s representation that those assumptions were reasonable (Ibid).“Accounting firms and their personnel must continually evaluate their client’s accounting and related disclosures, putting themselves in investor’s shoes.” (Ibid) Particularly troubling to the Board was the fact that Ernst & Young’s internal audit quality review inspection program discovered the problem with Medici’s sales return reserve estimate and“failed to appropriately address a material departure from GAAP regarding the company’s sales returns reserve” (Ibid). Many auditing violations that were identified by the PCAOB included:

1. Failure to exercise due professional care in the performance of the audit (PCAOB, supra).

2. Failure to disclose all significant accounting policies of Medicis as an integral part of the financial statements (PCAOB, supra).

3. Failure to appropriately consider or ensure the performance of audit procedures to consider contradictory audit evidence (i.e. sales returns not eligible for exchange treatment) PCAOB, accepted accounting principles (PCAOB, supra).

4. Failure to adequately consider whether any action was required to safeguard against future reliance on Ernst & Young’s audit report on the December 31, 2005 financial statements (PCAOB, supra).

5. Failure to consider subsequent disclosures of facts that existed at the date of the auditor’s report (PCAOB, supra).

6. Failure of Ernst & Young to obtain sufficient competent evidential matter to support Medici’s significant accounting estimates and key assumptions (PCAOB, supra).

7. Failure to adequately consider whether Medici’s change in methodology for estimating its sales returns reserve for“non-legacy” product returns needed to be disclosed in the entity’s Form 10-K (PCAOB, supra).

8. Issuance of an incorrect audit opinion (i.e. unqualified opinion) (PCAOB, supra).

In the end, the PCAOB concluded that Ernst & Young“failed to identify and appropriately address a material departure from U.S. GAAP” and performed audits“inconsistent with their obligations to exercise professional skepticism as the company’s independent auditor” (PCAOB, supra).

Second Bullet Strikes Medicis Too-Channel-Stuffing

After dismissal of the class action lawsuit by Judge Snow on December 1, 2009, the complaint was amended and discovery was undertaken (In Re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp., supra, 2011).

The lawsuit against Medicis claimed that the pharmaceutical company was“channel-stuffing.” (Edwards, 2011). This management sales technique involves claiming that extra product was sold to customers when management of the entity knows the unwanted stock would be returned (Ibid). Medicis was shipping drugs to sellers it knew would not be resold (Ibid). By doing so, Medicis was inflating revenues on paper, allowing it to show consecutive quarters of profits. When the expired product was returned, Medicis would book it at the same value as the returned product originally cost (Ibid). Essentially, this was“an accounting wash,” even though Medicis had to make two batches of the product, just to sell one (Ibid). Despite these management techniques, management informed investors and analysts repeatedly that“there was nothing unusual about Medici’s stocking policies” (Ibid). Shacknai, the CEO and founder, called it“a technical issue” (Ibid). Prygocki, the COO, stated that“the deferred tax asset has no impact on cash flow or corporate earnings” (Ibid). Neither of those statements turned out to be true. (Ibid).

Over 500,000 pages of documents, including the production of Ernst & Young’s work papers were reviewed (Ibid) and witnesses were deposed. The parties mediated the dispute that allegedly damaged 47.8 million shares of Medici’s common stock and another 45,200 stock options (100 shares each) (Ibid). Neither Medicis nor Ernst & Young admitted any wrongdoing, in the class action settlement agreement that was reached in 2011 (Ibid). Medicis and Ernst & Young continued to believe that its sales return reserve methodology“violations” resulted from a technical and unintentional misapplication of SFAS 48 and GAAP. Medicis and Ernst & Young admitted no fraud and no fraud motive was offered. The facts prove that the correct application of SFAS 48 would have resulted in a cumulative understatement of revenues and earnings during the period as a whole. Nevertheless, Medicis agreed to pay $11 million and Ernst & Young agreed to pay $7 million to settle the class action litigation (Ibid).

Questions

1. The PCAOB cited Medici’s auditor, Ernst & Young, for numerous violations of auditing standards. What auditing standards did Ernst & Young violate? How did Ernst & Young violate those auditing standards?

2. What did the PCAOB mean when it said Ernst & Young acted“inconsistent with its obligation to exercise professional skepticism as [Medici’s] independent auditor”? Is professional skepticism required in all audits?

3. Ernst & Young’s work papers were requested by the plaintiffs in the class action civil litigation. What are work papers? To whom do work papers belong? What purpose(s) do work papers serve? Why do you think Ernst & Young’s work papers were requested in the civil litigation against them?

4. What is the purpose of quality control in an audit firm? Is it required? What was deficient with Ernst & Young’s Audit Quality Review of the audit of Medici’s December 31, 2005 financial statements?

5. On February 8, 2012, the PCAOB assessed a $2 million civil penalty against Ernst & Young for its violations of PCAOB auditing standards in regard to audits of Medici’s financial statements. What additional penalties could the PCAOB have issued?

Teaching Notes

Learning Objectives and Implementation Guidelines

This real-world case can be employed in an advanced undergraduate auditing or a Master level auditing course. The Medicis case enables students to understand the complexity of audit engagements and to examine the issues of:

1. Management’s choice of significant accounting policies, key assumptions and estimates.

2. The auditor’s requirements to exercise due professional care and professional skepticism throughout the audit.

3. The importance of maintaining detailed, written auditor work papers to support evidence obtained and conclusions reached in an audit.

4. Quality Control In An Audit Practice.

5. The authority of the PCAOB to inspect and assess penalties against public accounting firms that audit publicly-traded companies.

The case questions encourage students to think critically about the relationship between Medicis (audit client) and Ernst & Young (auditor) under the watchful eye of the PCAOB. In addition, students are asked about the correct auditing procedures in this case. Therefore, they need to apply previously acquired theoretical knowledge from the class to this practitioner-oriented real-world scenario. This type of experiential learning should increase the student’s knowledge of the complex subject matter and better prepare students for their future careers in the auditing profession.

This case should be covered towards the end of a semester because prior knowledge of the main auditing procedures is necessary to discuss the case questions. There are two ways that students can work on this case:

1. Through an in-class setting, students can first read the case on their own and then discuss the case questions in small groups. The small groups can then either write up their solutions or the solutions can be discussed among the small groups in the classroom. This format can enhance student’s teamwork skills, as well as oral and written communication skills.

2. This case can be assigned to students as an individual homework assignment. This format requires students to think critically about the case questions individually. The instructor can then ask the students to either turn in a written discussion of the case questions and/or request the students to present their solutions as an oral presentation. This format would also enhance students written and/or oral presentation skills and would ensure that each student spends the necessary time to understand the application of the appropriate auditing rules and procedures.

In summary, we believe that this case increases a student’s ability to apply auditing rules and procedures to a real-world audit scenario. In addition, the student is made aware of the consequences that an inappropriate audit opinion can have on the client company, investors and the audit firm.

Questions and Suggested Answers

1. The PCAOB determined that Ernst & Young violated numerous accounting/auditing standards. What auditing standards were violated? How did Ernst & Young violate them?

The PCAOB determined that Ernst & Young failed to exercise due professional care in performing the audit of Medici’s financial statements ending December 31, 2005. Due professional care is to be exercised in the planning and performance of the audit and the preparation of the auditor’s report (AS 1015.01). The matter of due professional care concerns what the independent auditor does and how the auditor does it (AS 1015.04). An auditor should possess“the degree of skill commonly possessed” by other auditors and should exercise it with“reasonable care and diligence,” that is, with due professional care (AS 1015.05). At a minimum, the engagement partner should know relevant accounting and auditing standards and should be knowledgeable about the client (AS 1015.06). The engagement partner is responsible for the assignment of personnel and tasks and the supervision of members of the engagement team (AS 1015.06).

Ernst & Young and Jeffrey S. Anderson, the senior supervising partner, failed to meet this standard in the performance of the audit of Medici’s financial statements for the six months ending December 31, 2005. No member of the audit team informed the audit client that its estimation methodology was not in conformity with GAAP. Pursuant to AS 1015.06, an auditor must have, at a minimum, knowledge of the relevant, professional accounting and auditing standards. The failure to recognize a departure from GAAP is a lack of due professional care.

A second violation identified by the PCAOB was Ernst & Young’s failure to appropriately consider or ensure the performance of audit procedures that considers contradictory audit evidence (AU 333.04). If a representation made by management is contradicted by other audit evidence, the auditor should investigate the reliability of the representation made (AU 333.04). Based on the circumstances, the auditor should consider whether his or her reliance on management’s representation relating to other aspects of the financial statements is appropriate and justified (AU 333.04).

Ernst & Young accepted management’s estimation of the sales returns reserve without performing any meaningful inquiry or reference to sales returns history. Inquiry and an examination of historical returns were necessary to ensure that management’s estimate of the sales returns reserve was reasonable based on the facts and circumstances. If Ernst & Young had conducted further procedures with regard to the sales returns account, Ernst & Young may have reached a different conclusion.

The PCAOB indicated that Ernst & Young misapplied the meaning of“present fairly in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles” (AU 411.04). The independent auditor’s judgment concerning the“fairness” of the overall presentation of financial statements should be applied within the framework of generally accepted accounting principles. Without that framework, the auditor would have no uniform standard for judging the presentation of financial position, results of operations and cash flows in the financial statements (AU 411.03).

Ernst & Young misinterpreted SFAS 48 to permit management’s estimate of the sales returns reserve and, in so doing, permitted a material departure from GAAP on Medici’s financial statements. The auditor then proceeded to issue an unqualified opinion on those financial statements.

2. What did the PCAOB mean when it said Ernst & Young acted inconsistent with its obligation to exercise professional skepticism as [Medici’s] independent auditor? Is professional skepticism required in all audits?

Due professional care requires the auditor to exercise“professional skepticism” (AS 1015.07). Professional skepticism is an attitude that includes a questioning mind and a critical assessment of audit evidence. The auditor uses the knowledge, skill and ability required by the profession of public accounting to diligently perform, in good faith and with integrity, the gathering and objective evaluation of evidence (AS 1015.07). The gathering and objectively evaluating audit evidence requires the auditor to consider the competency and sufficiency of the evidence. Since evidence is gathered and evaluated throughout the audit, professional skepticism should be exercised throughout the audit process (AS 1015.08). The auditor neither assumes that management is dishonest nor assumes unquestioned honesty. In exercising professional skepticism, the auditor should not be satisfied with less than persuasive evidence because of a belief that management is honest (AS 1015.09).

The PCAOB criticized Ernst & Young for exercising a lack of professional skepticism which is required to be exercised in all audits. The acceptance of Medici’s methodology for estimation of the sales returns reserve by Ernst & Young was tantamount to a subordination of its professional judgment and auditor independence to the audit client. Ernst & Young’s actions demonstrated a lack of due professional care required in all audits. As a result of its actions, Ernst & Young received the largest civil penalty of $2 million issued by the PCAOB as of that date. Several of the individual audit partners of Ernst & Young were also fined by the PCAOB for their roles in Medici’s December 31, 2005 financial statements audit.

3. Ernst & Young’s work papers were requested by the plaintiffs in the class action civil litigation. What are work papers? To whom do work papers belong? What purpose(s) do work papers serve? Why do you think Ernst & Young’s work papers were requested in the civil litigation against them?

Work papers (or working papers) are audit documentation. The work papers are the property of the auditor. Auditors support the conclusions in their [audit] reports with a work product called audit documentation, also referred to as working papers or work papers (AS 3.A3). Audit documentation also facilitates the planning, performance and supervision of the engagement. They provide the basis for the review of the quality of the work by providing the reviewer with written documentation of the evidence supporting the auditor’s significant conclusions. Examples of audit documentation include memoranda, confirmations, correspondence, schedules, audit programs and letters of representation. Audit documentation may be in the form of paper, electronic files, or other media (AS 3.A3).

The PCAOB regards audit documentation as“one of the fundamental building blocks on which both the integrity of auditors and the Board’s oversight will rest.” The quality and integrity of an audit depends on the existence of a complete and understandable record of the work the auditor performed, the conclusions the auditor reached and the evidence the auditor obtained that supports those conclusions (AS 3.A4).

Audit documentation may be reviewed by the PCAOB to fulfill its mandate to inspect registered public accounting firms to assess the degree of compliance of those firms with applicable standards and laws (AS 3.A4). Audit documentation, or working papers, belongs to the auditor. The working papers must demonstrate that audit work was done in a professional manner and supports the auditor’s opinion on the financial statements. The PCAOB’s investigation of Ernst & Young’s audit work papers revealed many violations of PCAOB auditing standards.

In connection with litigation against an auditor, such as Ernst & Young, a litigant reviews the work papers to ascertain the nature of the work performed, the persons who performed and reviewed the work and the related dates that work was performed or reviewed. In a class action lawsuit, litigants seek evidence that the auditor failed to audit Medici’s financial statements in a reasonable manner or that the auditor reached conclusions without sufficient appropriate evidence.

4. What is the purpose of quality control in an audit firm? Is it required? What was deficient with Ernst & Young’s Audit Quality Review of the audit of Medici’s December 31, 2005 financial statements?

A CPA firm must have a system of quality control for its accounting and auditing practice that describes elements of quality control and other matters essential to the effective design, implementation and maintenance of the system (QC 20.01). The AICPA requires, among other things, that“members should practice in firms that have in place internal quality control procedures to ensure that services are competently delivered and adequately supervised” (QC 20.02). A firm’s system of quality control encompasses its policies and procedures (QC 20.03).

The quality control system also encompasses the firm’s organizational structure and the policies adopted and the procedures established to provide the firm with reasonable assurance of complying with professional standards. The nature, extent and formality of a firm’s quality control policies and procedures should be appropriately comprehensive and suitably designed in relation to the firm’s size, the number of its offices, the degree of authority allowed its personnel and its offices, the knowledge and experience of its personnel, the nature and complexity of the firm’s practice and appropriate cost-benefit considerations (QC 20.04). Inherent limitations that reduce a quality control system’s effectiveness include variances in an individual’s performance and understanding of (a) professional requirements, or (b) the firm’s quality control policies and procedures (QC 20.05).

The elements of quality control system’s policies and procedures, applicable to a firm’s accounting and auditing practice should include: (a) independence, integrity and objectivity; (b) engagement performance; and (e) monitoring (QC 20.07). Policies and procedures should be established to provide the firm with reasonable assurance that the work performed by engagement personnel meets applicable professional standards, regulatory requirements and the firm’s standards of quality (QC 20.17). Policies and procedures for engagement performance encompasses all phases of the design and execution of the engagement…and should cover planning, performing, supervising, reviewing, documenting and communicating the results of each engagement (QC 20.18; AS 7, Engagement Quality Review).

Ernst & Young had, in place, an Audit Quality Review team as part of its quality control system. Its goal was to review the audit of Medici’s December 31, 2005 financial statements. The review team, however, included the senior partner of the audit engagement team. Consequently, when the Audit Quality Review team identified the issue with regard to Medici’s methodology used to calculate its sales return reserve, it was reluctant to require a restatement to its audit client. Instead, it settled on the adoption of an alternate accounting principle to justify the estimate. A truly, independent Audit Quality Review team may have reached a different decision, such as re-auditing the period previously audited.

5. On February 8, 2012, the PCAOB assessed a $2 million civil penalty against Ernst & Young for its violations of PCAOB auditing standards in regard to audits of Medici’s financial statements. What additional penalties could the PCAOB have issued?

Pursuant to Section 105 (c) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, the PCAOB may impose:

1. Temporary suspension or permanent revocation of registration of a public accounting firm’s registration under the act.

2. Temporary or permanent suspension or bar of a person from further association with any registered public accounting firm.

3. Temporary or permanent limitation on the activities, functions, or operations of such firms or person(s) associated with the such firms.

4. A civil money penalty for each such violation in an amount equal to: (i) not more than $100,000 for a natural person, or $2,000,000 for any other person; and (ii) in any case which intentional or knowing conduct, including reckless conduct, applies, not more than $750,000 for a natural person, or $15,000,000 for any other person.

5. Censure.

6. Required additional professional education or training.

7. Any other appropriate sanction provided for in the rules of the [PCAOB].

Ernst & Young received the maximum monetary civil penalty of $2 million from the PCAOB at that time.“The fine underscores the severity of the audit failure and sends a message to the profession.” (Nasiripour, 2012).

References

- Allergan Rejoices. (2009). Accounting error puts spotlight on solodyn weakness. CBS Money Watch/CBSNews.com

- Edwards, J. (2011). Medicis settles case alleging CEO Shacknai cooked the books. CBSNews.com

- In Re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp. (2011). United States district court for the district of Arizona, case no. CV 08-1821-PHX-GMS.

- In Re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp. (2011). United States district court for the district of Arizona, case no. CV 08-1821-PHX-GMS.

- Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation. (2015). Bloomberg news.

- Nasiripour, S. (2012). Ernst & young fined record $2 M over audit. The Financial Times.

- PCAOB News Release. (2012). PCAOB announces settled disciplinary order for audit failures against Ernst & young and four of its partners.

- PCAOB Release (2012). Order making findings and imposing sanctions: No. 105-2012-001.

- Whitehouse, T. (2012). PCAOB action illuminates returns accounting. Compliance Week.

- Whitehouse, T. (2013). Auditors are seeking more information from internal investigations. Compliance Week.