Research Article: 2019 Vol: 11 Issue: 1

Conflict in Supply Chain Order Filler Behavior: An Organizational Citizenship Behavior Investigation

Rachelle F. Cope, Southeastern Louisiana University

Robert F. Cope III, Southeastern Louisiana University

Anna N. Bass, Southeastern Louisiana University

Abstract

In our work, we examine the effects of supply chain Distribution Center (DC) order filler wage incentives and performance on Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB). OCB is a term relating to voluntary actions of employees to help their fellow employees and/or their organization through efforts that are not part of a contractual obligation. A key feature of OCB is that it is not rewarded in a formal manner. Through the years, OCB has gained substantial interest and has been studied across many organizational domains. Most supply chain DCs offer accelerated pay incentives for employees with advanced skills of increased speed, higher quality, and reduced damage in their job duties. While accelerated pay incentives are desirable, they may come at the cost of hindering positive OCB characteristics in organizations. We address some of the conflicts in OCBs that benefit the individual versus the organization. In particular, we explore the roles of job cross-training and culture change in fostering OCBs that benefit the organization.

Keywords

Supply Chain, Distribution Center, Order Filler, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, Economics.

Introduction

An organization’s culture is the essence of how its people interact and work. However, it is a complex entity that survives and evolves mostly through gradual shifts in leadership, strategy, and other circumstances. More simply, culture is the self-sustaining pattern of behavior that determines how things are done (Katzenbach et al., 2016). In any organization, the formation of a favorable culture is a continuing, yet elusive goal. Thus, the study of employee behavior in the workplace has been an ongoing topic of interest for decades. Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) is a term that attempts to capture a component of a company’s culture- specifically, the degree to which voluntary actions of employees are done without contractual obligation for the purpose of helping fellow employees. OCB is witnessed in all organizations at all levels. In our work, we study the nature and activities of Distribution Centers (DCs) and the impact of this environment on OCB.

DCs focus on a series of activities that are necessary to move items from manufacturers to customers. The efficiency and accuracy of these activities are of key importance in the success and profitability of a firm during this intermediate phase of the supply chain. DCs offer many economic benefits for companies. For example, one economic benefit is derived from the ability to consolidate products from a number of production plants into manageable shipments delivered to retailers and customers.

It is common practice for DCs to offer pay incentives for employees who demonstrate high levels of speed and efficiency in their order filling. Daily tasks for order fillers might include receiving and filling customer orders, picking merchandise from warehouse shelves, packing merchandise, checking packed merchandise against written orders for accuracy, and using automated or computer-based technology to keep track of inventory and shipments. With order fill rates determining wage, skilled employees often take advantage of bonus pay for achieving higher fill rates (Bowersox et al., 2013). Several questions arise as order fillers capitalize through increased order filling rates:

1. Do they encourage or discourage fellow employees also to achieve bonus pay?

2. Does this create competition among order fillers?

3. Does this promote or inhibit characteristics of OCB?

Our work attempts to answer these questions and provide a framework that ensures a culture of work quality and efficiency, while fostering and promoting OCB within DC environments.

Literature Review

Distribution Center Work Descriptions

A DC is not a typical warehouse; a DC receives bulk shipments through economical long-distance transportation from a plant and breaks them into small shipments for local delivery to various customers. In a DC, the storage of goods is limited or nonexistent. As a result, DCs focus on receiving, put away, order picking, order assembly, and shipping, as well as the collection and reporting of information (Higginson & Bookbinder, 2005).

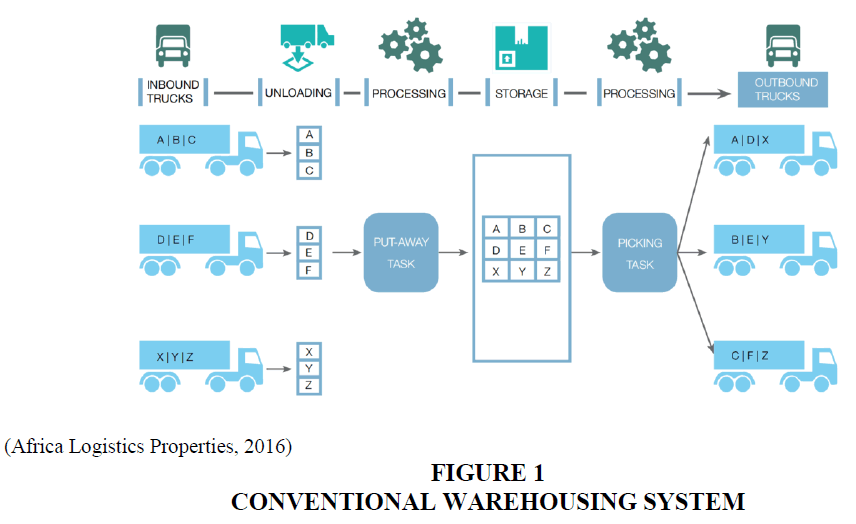

The key rationale for DCs is the reduction in transportation cost by consolidating movement. Several plants supply their products for customers through a warehouse, and from this warehouse the products are sent in smaller quantities to retailers and customers. Another common term for the activities at a DC is cross-docking, which enables receipt of full shipments from a number of suppliers (generally manufacturers). Direct distribution is provided to customers without storage. As soon as the shipments are received, they are allocated to their respective customers and are moved across the loading dock to a vehicle for the onward shipments to the respective customers. Figure 1 illustrates the conventional service of a DC.

Economics of Distribution Centers

DCs offer many economic benefits for companies. One economic benefit of a DC is derived from the ability to consolidate products from a number of production plants into manageable shipments for delivery to retailers and customers. DCs allow production to be postponed or delayed until actual demand is certain. Once demand is determined in terms of product type and quantity, minor processing can quickly make final products available, reducing inventory requirements. In addition, DCs provide buffers for seasonality, improve production efficiency, and support marketing efforts that often send logistics managers scrambling to meet surges in demand. In a DC environment, nothing is produced or consumed; all products that come into the DC are transported out (Bowersox et al., 2013).

Like any other entity in the supply chain, DCs exist to be profitable. Therefore, it is important to understand the economic trade-offs in DC operations. DCs are under increasing pressure to reduce costs and increase margins. Companies that have conducted workflow process reviews indicate that picking is a key area where cost savings can most easily be achieved (Intermec, 2013). Order picking metrics measure whether an order is picked in its entirety, error free, damage free, and delivered on time. “Touches,” or points at which employees move products, increase product cost. Picking directly to a shipping carton instead of to an intermediate bin or tote is just one example of how unnecessary steps can be eliminated in the distribution center process. When superfluous steps are eliminated, the process becomes faster and more streamlined. This operational efficiency enables DCs to regain time and improve overall cost savings.

Methodology

Order Filler

“Order filler” is the official title the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) gives to warehouse workers who receive, unpack, and track merchandise. As of 2016, over 2,000,000 Americans worked as order fillers. One-third of jobs in this field are part-time jobs. In addition to the numerous duties previously mentioned, they often use handheld RFID scanners to assist with their jobs. Consequently, order fillers must possess basic literacy and computer/digital device knowledge as well as the ability to perform under pressure. Order clerks earned a median annual salary of $23,840 and median hourly wages of $11.46 in 2016. While employment in this occupation is expected to grow only as fast as 5% to 8% between 2016 and 2026, according to BLS, job prospects are quite good. It is estimated that nearly 270,000 more warehouse jobs of this type will exist by 2026 (U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016).

Duties of the Order Filler

Despite the widespread automation of DCs, a largely human component exists in the duties performed in these facilities. Although the duties of order fillers are consistent and mostly uniform across DCs, there may be some variation in training and skill levels of order pickers. For example, the educational background needed for these entry-level positions is typically a high school diploma (or equivalent) along with considerable on-the-job training. Since warehouses are often open around the clock, order fillers may have to work during the day or overnight, including weekends and evenings. Workers at most of the major employers typically have shifts that last from 10 to 12 hours. Order fillers must spend a significant amount of time on their feet, either standing still or moving rapidly around the facility. Applicants for these jobs must be prepared to lift heavy items, some weighing as much as 70 pounds, depending on the facility. Warehouses are very noisy places, and order fillers may need to wear equipment to protect their hearing. Temperatures in distribution centers can be extreme; workers who spend time on loading docks may be exposed to very hot or very cold weather, depending on the season.

Pay Structure for Order Fillers

The nature of the pay structure is of particular importance in our study. In addition to workers’ regular and overtime pay, additional components may contribute to the wage, accounting for speed, quality, and damage. For workers, DCs track their cases (units per hour/day) as a measure of productivity. Speed should not affect the quality of the job; in addition to speed, workers are tracked on the percent of cases ordered that are shipped as requested. Moreover, their percent of order lines and customer orders filled completely are monitored. At the same time, a damage component keeps track of the percent of items that are unfit for delivery. Workers are aware that their wage will increase as a function of their associated order targets. As their speed increases with experience, wages are adjusted for productivity. Improvements with higher quality and fewer damaged items can also lead to wage increases. Another characteristic of DCs is that the amount of work is generally fixed (demand is known). This characteristic may create competition between top performers who are trying to maximize their earnings. When some workers fill more orders, co-workers are left with less work and consequentially, less wage opportunity. This situation raises a very important issue for DC managers: Are wage incentives affecting morale among order fillers?

Employees Leveraging Employment

An observed behavior among order fillers is their perception of the importance of the output to the overall productivity of the DC by top performers. These top performers often gain the feeling that they are indispensable. In spite of understanding their importance to the DC, many top performers continually look for outside work opportunities. Another opportunity often motivates workers to leave their job at the DC in order to take on a higher-paying, temporary, full-time position. Although this strategy seems illogical, workers know that they have a high likelihood of being rehired at the DC when their temporary job has ended. DCs know the value of the skills order fillers have acquired during their previous work experiences, so they are willing to return the order fillers to their job rather than investing in training a new, inexperienced employee.

Top performers who leave their positions create significant speed, quality, and damage variances in overall DC output. This is particularly true at certain high-demand times of the year. The paradox of this situation is that top-performing order fillers may quit their jobs for periods of time, yet are welcomed back with open arms when reapplying for their previous positions-often with the same wage and pay structure. Thus, the question of employee “citizenship” is raised.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB)

The phrase “Organizational Citizenship Behavior” was first used by Smith et al. (1983) to denote organizationally beneficial behavior of workers that is not prescribed, but occurs freely to help others achieve the task at hand. OCB emphasizes the social context of the work environment in addition to the technical nature of the job. OCB has been defined in terms of pro-social behavior, altruism, and service orientation. Usually these behaviors are not monitored by the organization’s reward system but provide the organization with a long-term social advantage. It is true that what is considered OCB in one organization may not be considered OCB in another; for this reason, research has been conducted to assess OCB in many different organizational settings. The fact that the duties of DC order fillers require actions that cannot adequately be prescribed in a job description makes OCB an important aspect in DC environments (DiPaola & Hoy, 2005). It should also be noted that OCBs do have the potential to take time from formal job roles to the extent that the main focus of the role is compromised. Consequently, it is important to ensure that OCB, while a positive force, is not competing with intended work objectives (Pickford & Joy, 2016).

Results and Discussion

Observed Dimensions of OCB

Research conducted in order to define the dimensionality of OCB in organizations has provided conflicting results. The research has been grouped into two main themes for analyzing or promoting OCB. There appears to be support for a two-factor model to define OCB according to the beneficiary of the OCB (Williams & Anderson, 1991) with the following two factors:

1. OCB that benefits the organization in general, such as volunteering to serve on committees.

2. OCB that is directed primarily at individuals within the organization, such as altruism and interpersonal helping.

Correspondingly, Organ (1988) defines the basic types of behavior that contribute to OBC as follows:

Altruism – employee’s helping behaviors

Conscientiousness – employee goes beyond minimum role requirements

Civic Virtue – employee deeply concerned about life of organization

Sportsmanship–employee’s willingness to tolerate less-than-ideal organizational circumstances without complaining (rolling with the punches)

Courtesy – preventing work-related conflicts as well as being polite and considerate

In order to apply these findings to work environments, understanding examples of the behavior characteristics described by Organ is a useful way to identify and encourage OCBs in employees. First, individual employee’s exhibited forms of OCB may stem from different motivations. For example, courtesy may be motivated by image management for one employee and by quality of work for another. Also, a single OCB may serve more than one motive, as in the case when conscientious employees work extra hours for contribution to excellence versus opportunity for promotion. Altruism may be displayed by individuals in accordance with personal goals in both long-and short-term dimensions. For example, an employee may drive a boss to work as an immediate helping gesture, but also realize the possible long-term benefit for this act of kindness. “Civic virtue” is achieved by giving new recruits tips on working with company resources. If an employee switches shifts or covers for another co-worker, sportsmanship is present when the facilitating employee does so willfully.

As an extension of fundamental OCB theory, Podsakoff et al. (2009) showed the need to determine justification for OCB’s ability to enhance organizational performance (in their study of work group performance). They identify possible factors as one or more of the following:

1. Reduce the need to devote scarce resources to purely maintenance functions.

2. Free resources for more productive purposes.

3. Enhance co-worker and managerial productivity.

4. Serve as a means of coordinating activities between team members and across groups.

5. Enhance the organization’s ability to attract and retain the best people.

Motivating Forces of Organizational Citizenship Behavior

As an extension of the foundations of OCB previously mentioned, a comparative analysis of motivational bases of helping forms of OCB was conducted by Settoon & Mossholder (2002). The study performed in this research examined the relative influence of variables reflecting different views of helping behaviors. The following variables were studied: task-focused citizenship behaviors, person-focused citizenship behaviors, co-worker support, trust, perspective-taking, empathetic concern, network centrality, and initiated task interdependence. Using these variables, several hypotheses were tested:

H1: Co-worker support will be associated with person-focused OCB.

H2: Trust will be associated with person-focused OCB.

H3: Perspective-taking will be associated with person-focused OCB person.

H4: Empathic concern will be associated with person-focused OCB.

H5: Empathic concern will mediate the relationships of co-worker support, trust, and perspective-taking with person-focused OCB.

H6: Network centrality will be associated with task-focused OCB.

H7: Initiated task interdependence will be associated with task-focused OCB.

As hypothesized, co-worker support, trust, perspective-taking, and empathic concern were correlated with person-focused OCB. Also, preliminary support for Hypothesis 6 was found as network centrality was positively related to task-focused OCB. Results indicated that the importance of each variable in predicting helping behavior varied depending on the type of behavior being predicted. Although the degree of influence was stronger for some variables than others, each hypothesis was validated. The findings of Settoon & Mossholder’s study may suggest an alternative reason for the connection of trust and citizenship behavior and clearly indicate that empathy assumes an important role in trust relationships. Interestingly, co-worker support was correlated with person-focused OCB but exhibited neither a direct nor a mediated relationship with person-focused OCB in their final model. They also hypothesized that co-worker support may create a feeling of indebtedness among individuals and a concomitant desire to reciprocate positive actions directed toward them. The lack of support for a link between co-worker support, empathy, and person-focused OCB in the final model suggests that although it may include both calculative and social elements, the basis of person-focused OCB may be less calculative and less embedded in a tit-for-tat exchange. Trading assistive behaviors quid pro quo may diminish the intrinsic value of relationships. Specifically, in high-quality relationships, individuals are not prone to help for the purpose of directly obligating others or to reciprocate a good deed. These findings are of interest in a DC environment as they apply to the relationships among order fillers.

Application to Distribution Center Order Fillers

Although both wage incentives and OCB are considered positive strategies/forces that benefit DCs, an inherent risk is present when these forces combine. As previously mentioned, demand for DC order fillers remain mostly stable (or slightly increasing) each day. When order fillers are highly motivated by wage incentives (beneficial to the individual), the desire to display the five OCB characteristics is diminished. Furthermore, the risk exists that the organization will start to consider an original display of OCB characteristics as increasingly compulsory. For order fillers who demonstrate OCB, lack of reward from the organization or lack of reciprocal OCBs from co-workers who received helping behaviors may damage organizational morale and employee motivation. Likewise, order fillers who demonstrate a disregard for OCB characteristics by quitting their job for other short-term opportunities should incur a penalty. When employees realize that they are “Indispensable,” whether through rehiring or further chance of promotion, OCBs tend to decline.

In order to foster OCBs in DCs, top-down support must be present for the culture changes necessary to promote the five OCB characteristics. Without support across all levels of management, OCB initiatives will not be viewed as a vital component of positive organizational culture. In addition to the inherent motivation for operational efficiencies for economic benefit, management needs to fully understand the impact of the OCB characteristics discussed. Altruism, conscientiousness, civic virtue, sportsmanship, and courtesy should not be viewed as trivial gestures, but the foundation of a culture with strategic priorities. Two possible strategies to foster OCB characteristics could include cross-training and a modified wage structure.

Conclusion

OCB involves a variety of employee actions that are not included as part of their assigned roles but go beyond that which is expected. When these noncompulsory actions benefit the organization, OCB is a beneficial aspect of the organizational culture. Our study described the foundations of OCB and observed the phenomenon in the setting of DC activities. In particular, the interaction of order filler incentives and OCB characteristics were considered.

Overall, OCB is considered a positive force in this setting where it serves to increase overall DC productivity. Thus, top performers must be motivated to serve as role models. Since productivity and quality metrics are recorded for all employees, the goal is to encourage all order pickers to continually improve in these areas. However, in the situation where the number of orders to be picked is fixed and the wage structure is formulated without consideration of the detrimental effects on OCB, the two forces that are fundamentally complementary may become competing.

Finally, areas of future research include a mechanism for service organizations to better understand the practices that are necessary to allow OCBs to emerge. OCBs can help an organization achieve a strategic advantage when the balance of these behaviors contributes to a positive and productive work environment. These areas include differentiating behaviors that are beneficial to the organization and the individual. By connecting these principles to organizational goals, employers can expect higher-quality work and increased performance in order filling. For example, a first step is for organizational leaders to exemplify those behaviors that are desirable in their employees in a social work setting. If workers see leaders displaying consideration, jumping in to help when needed, and giving their time to participate in outside events, they are more likely to do the same. Furthermore, leaders need to encourage and practice teamwork. It is important to establish a culture which promotes collaborative efforts. If workers are exposed to this type of cooperation early on, they will be able to better see their vital role in the organization.

The purpose of this research was to investigate the competing effects of OCB and wage incentives among order fillers in DCs. Through this study, the research can be extended to other areas of Supply Chain Management. In particular, other warehouse operations, production, transportation, and retail are applicable.

References

- Africa Logistics Properties (2016). Warehouses as Distribution Centers. http://www.africawarehouses.com/distribution-centres

- Bowersox, D., Closs, D., & Cooper, M. (2013). Supply Chain Logistics Management. (Fourth edition). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- DiPaola, M., & Hoy, W. (2005). School characteristics that foster organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of School Leadership, 15(4), 387-406.

- Higginson, J. & Bookbinder, J. (2005). Distribution Centers in Supply Chain Operations. In: Langevin, A. and D. Riopel (Ed.). Logistics Systems: Design and Optimization. New York, 67-91.

- Intermec (2013). Unlocking Hidden Costs in the Distribution Center. Research report by Intermec Technologies Corporation.

- Katzenbach, J., Oelschelegel, C., & Thomas, J. (2016). 10 Principles of Organizational Culture. Strategy+Business, (82), 1-7.

- Organ, D. (1988). Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Pickford, H., & Joy, G. (2016). Organizational citizenship behavior: Definitions and dimensions. Saïd Business School Research, MIB Briefing No.1.

- Podsakoff, N., Podsakoff, P., Whiting, S., & Blume, B. (2009). Individual- and Organizational-Level Consequences of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 122-141.

- Settoon, R., & Mossholder, K. (2002). Quality and relationship context as antecedents of person-and task-focused interpersonal citizenship behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 255-267.

- Smith, C., Organ, D., & Near, J. (1983). Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(4), 653-663.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). Occupational Employment Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/oes/home.htm.

- Williams, L., & Anderson, S. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behavior. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601-617.