Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Cultural Factors in Chinese Family Business Performance in Thailand

Tossapon Luechapattanaporn, Asian Institute of Technology

Winai Wongsurawat, Mahidol University

Abstract

The purpose of this research was to investigate the cultural characteristics of Chinese family business in Thailand and to identify how these characteristics contribute to business performance. A qualitative-led mixed methods strategy was used, incorporating with a business questionnaire (n = 380) and interviews with owners and managers of firms (n = 5). There were three distinct types of practices and values that were identified as unique to Chinese family businesses, namely renqing (reciprocity), guanxi (network relationshisp), and Confucian values (benevolent leadership, prioritising family, and exchanging favours). These values enabled the firm to increase resource access and capacity, to focus on mutual benefit, to meet deadlines and production requirements, to improve internal trust and relationships, and to create long-term relationships. Such practices, however, may also contribute to corruption and poor management. Thus, these cultural factors do create competitive advantage, but must be used carefully.

Keywords

Family Firms, Renqing, Guanxi, Confucian Values, Business Performance.

Introduction

Family firms are the foundation of the Thai economy. One estimate indicated that 50.4% of firms listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) were family owned, and over 70% of Thailand’s GDP is attributable to family firms (Apisakkul, 2015). Family firms in Thailand are also distinct from other firms in terms of their business strategies and practices. For example, family firms are more likely to invest in long term business activities (Connelly, 2016). While family firms may be more likely to rely on traditional management practices and do not always have professional management, they are increasingly following modern business practices and strategies and developing internal management capabilities and resources (Yabushita & Suehiro, 2014). Thus, despite the image of the family firm as old fashioned and non competitive, in practice family firms are dynamic and modern, representing a key economic force for Thailand.

Despite an external appearance of cultural homogeneity, in fact Thailand has many distinct ethnic groups. The Thai Chinese ethnic group is noticeable for its dominance of the business sector of Thailand. This group has a long history, with the first Thai Chinese businesses established as trading businesses during the later Ayutthaya period of Thai history (circa 1350 to 1767) (LePoer, 1987). By the 1930s, the Thai Chinese ethnic group were predominant in the business sector, and continue to hold this position despite slowing immigration (Baker & Phongpaichit, 2014). Many of the family firms in Thailand are owned by Chinese families. Furthermore, these firms are associated with higher than average economic impact because of higher levels of foreign direct investment (FDI) (Ordóñez d Pablos & Lytras, 2010). These authors also estimated that Chinese firms controlled 90% of total investments and about 50% of finance in Thailand.

The question this research addresses is two fold. First, to what extent do Thai Chinese family firms share the generalised characteristics of Chinese family firms? And second, how do these characteristics contribute to the firm’s performance? Generalised characteristics of Chinese family businesses include the initial entrepreneurial origin, leadership and management by family members, roles and obligations associated with the family, and gradual growth and diversification (Tokarcyzk et al., 2007). However, these characteristics are shared by family firms around the world and do not necessarily differentiate the Thai Chinese family firm. Instead, the research turned to cultural values and underlying norms.

This study used a mixed methods approach to investigate this question, finding three underlying cultural norms that could differentiate Thai Chinese family firms from others. These factors included renqing (enduring obligation), guanxi (network relationships), and Confucian values of benevolent leadership, prioritisation of family interest, and exchange of favours.

Literature Review

Business Performance

The outcome of interest in this study was business performance. Business performance is a complex and multidimensional concept, which can be measured using economic outcomes such as earnings and profits, sustainability measures such as environmental and social impact, or internal operational and organisational perspectives such as efficiency, quality, or employee satisfaction, as well as many other dimensions (Lebas & Euske, 2004). This means that business performance is an ambiguous and to some extent subjective measure, with the appropriate outcomes depending on the business’s strategic objectives as well as the information available (Walker & Brown, 2004). For example, family businesses may be more interested in long term investment performance, rather than short term revenue generation (Connelly, 2016).

Thus, while business performance can be defined generally as the extent to which the business achieves its strategic or operational objectives, there is no single set of measures that can be used to evaluate business performance. Studies can use financial performance measures (Paladino, 2011), which are considered objective, but many of the firms included in the study are privately owned and do not release public financial information. Non financial measures are not considered objective, but they are associated with the firm’s financial performance (Fullerton & Wempe, 2009; Paladino, 2011). Therefore, a choice of non financial and financial subjective measures was used, to enable comparison of perceived performance.

Chinese Family Firms

This research is concerned with Chinese family firms. Chinese family firms are in general similar to other types of family firms around the world, with characteristics like ‘familyness’, an entrepreneurial origin, operation and leadership by family members, enduring roles and obligation and gradual growth, diversification and eventually internationalization predominating (Tokarcyzk, et al., 2007). However, the Chinese family firm also has some unique characteristics. For example, these firms and their owners often have extensive networks of family, friends and business owners spread throughout the world, especially in areas such as Southeast Asia where there has been extensive Chinese migration (Poutziouris, Wang, & Chan, 2002). These network relationships are used as the basis for internationalisation and long term supply relationships, creating significant competitive advantage for the firm (Pananond, 2007).

As Pananond (2007) notes, Thai Chinese family firms are very typical in this respect. Another difference between Chinese family firms and others is the underlying cultural values specific to Chinese culture (Hofstede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010). While there is certainly no guarantee that cultural values of Thai Chinese family firms are entirely consistent with those of firms in China, these values may continue to play a role for Chinese diasporic firms (Pananond, 2007).

Cultural Values of Chinese Family Firms and Business Performance

This study evaluated three cultural values associated with Chinese family firms, which include renqing, guanxi, and Confucian values.

Guanxi

Guanxi is a general term for the establishment, maintenance, and passing on of social ties between individuals and groups (Chen & Chen, 2004). These networks form first through mutual acquaintance, followed by development of trust and social capital, which is then extended to others in the individual’s network (Ramos, 2016). Thus, guanxi can be characterised as more of a network of networks than a relationship of individuals. Typically, guanxi networks are developed by individuals, but they benefit families (Soleimanof, Rutherford, & Webb, 2018).

Guanxi networks are a significant source of competitive advantage for Chinese family firms because they offer extended resource and capability access (Banalieva, Eddleston, & Zellweger, 2015). Guanxi is therefore associated with positive firm performance (Ramos, 2016). However, it also has problems. Guanxi tends to be exclusionary, which can make it easy for insiders to do business with firms within a network but difficult for outsiders (Sternad & Kennelly, 2017). It is also associated with corruption, especially in Western cultures where it is perceived as an unfair advantage by firms that do not have access to these networks, or where it is too heavily relied on (Dinh & Calabró, 2019).

Renqing

Renqing, which simply translates to ‘human feeling’, is the obligation that incurs not through social relationships (as with guanxi) but instead with emotional engagement with others (Chan, 2006).Renqing is less frequently investigated than either Confucian values generally or guanxi because, as Chan (2006) points out, it is associated more with the rural past than with modern business. However, there are several aspects of renqing that are relevant to the firm’s performance. One of these aspects is the open ended, reciprocal exchange of gifts or bao, which can be characterised in the workplace as exchange of help and assistance (Chen & Peng, 2008; Xu, 2012). Personal relationships and caring within the organisation are also expressions of renqing within the workplace (Chan, 2006). Unlike guanxi, the extent to which renqing is relied on instrumentally will depend on the extent of the personal relationship between those involved (Chen & Peng, 2008). Thus, the two concepts cannot be considered to completely overlap.

Confucian values

Both guanxi and renqing are underlying assumptions of Confucian values, which are a set of moral and ethical principles derived from the work of Chinese philosopher Confucius (Tu, 2008). Although Confucian values were deprecated during the rise of the modern Chinese state, they have been somewhat renewed with the revival of a market economy in China, and have continued to be commonplace in diasporic communities (Tu, 2008).

Modern Confucian values can be understood as five distinct values, which include junzi (the moral person); core virtues (ren, yi, and li, or compassion, morality, and observance of manners and norms); guanxi, and harmony (Ip, 2009). These values tend to result in specific social structures, including filial piety and prioritisation of family, benevolent dominance, and public role modelling of virtuous behaviour (Li & Kell'i Akina, 2014). Ip (2009) argued that Confucian values may permeate all areas of the firm’s operations, ranging from its strategy direction and operational practices to its internal structure and flows of power to its recognition and treatment of stakeholders. Studies have shown that Confucian values are observable in Chinese firms outside the cultural context, expressed in areas like managerial self regulation (Woods & Lamond, 2011) and leadership (Low, 2010). Therefore, Confucian values are expected to play a role in the performance of the firm.

Conceptual Framework

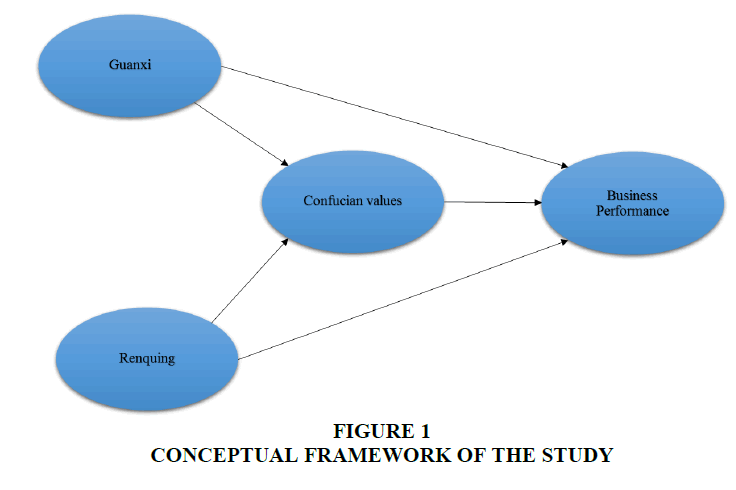

The conceptual framework of the study (Figure 1) follows the literature above in its proposal of relationships between the factors. These hypotheses all apply specifically to Chinese family firms in Thailand.

The conceptual framework begins with the role of guanxiand renqing in Confucian values, proposing that both play a significant role in the expression of Confucian values:

Hypothesis 1: Guanxi is a significant influence on Confucian values in the firm.

Hypothesis 2: Renqing is a significant influence on Confucian values in the firm.

The second stage of the conceptual framework relates to the effect ofguanxi, renqing and Confucian values as an influence on business performance of the firm:

Hypothesis 3: Guanxi significantly influences business performance.

Hypothesis 4: Renqing significantly influences business performance.

Hypothesis 5: Confucian values significantly influence business performance.

Methodology

This research used a cross sectional, explanatory, qualitative led mixed methods approach, which was selected because of its ability to both describe and explain the research situation (Saunders et al., 2009). The research was sequential, with a large quantitative study followed by a small scale qualitative study.

Quantitative Study

The quantitative research used a questionnaire to collect data on the three identified cultural values, including guanxi (5 items), renqing (6 items), Confucian values (six items), and business performance (6 items), at the employee level (Table 1). The questionnaire was designed by the researcher, and used Cronbach’s alpha to test for internal consistency. Although the guanxi scale did have a lower than ideal alpha value (with a minimum threshold of 0.7), no single item was obviously poorly correlated. Therefore, considering that alpha consistently underestimates the likely consistency of the scale (Peteron & Kim, 2013), the scale was kept as is.

| Table 1 Summary of the Questionnaire and Internal Consistency (Cronbach's ?) | ||

| Variable | Items | Alpha |

| Guanxi | Establishment and maintenance of relationships both at an individual level and a firm level is very important. In your company, exchange of favors and information is often seen. Your leader often gives you a gift on a special occasion. You are always concerned for feelings of other members of your company. You can trust people in your company. | 0.68 |

| Renqing | In your company, giving back to others is very important. Your leader always assists you on work-related problems and you always help him/her back. Your leader usually cares about problems in your society. You always are concerned with other’s feelings. You usually exchange favors with other members in the company. It is your obligation to help other members in the company who are in trouble. | 0.791 |

| Confucian Values | Your family’s interests always come first. Family roles are of great importance in your working environment. Your leader always makes decisions based on right and wrong. You have an honest and kind leader. In your company, relationships with others are very important. In your company, you normally work together to achieve goals. |

0.709 |

| Business Performance | You have an effective management system. You have an effective marketing team. Number of new customers at your company is increasing. Your company’s profit has increased. Your company is expanding. Overall, your company’s performance is excellent. |

0.844 |

The level of analysis for the research was the firm level. However, the perspective of interest was that of the employee within the firm. Therefore, the population of interest was employees of Chinese family firms. A snowball sampling approach was employed, with the researcher initially contacting people who were known to be employed in Chinese family firms to participate in the research. Those who completed the survey were asked to refer other Chinese family firm employees to the questionnaire. Respondents were contacted through the online social media site LINE and in person, through visiting the business. This approach was chosen to balance the need for a geographic reach of the sample and ensuring that those who do not use social media sites (about 24% of Thailand’s population) are represented. Since there are no official statistics about Chinese family firm employees, the sample is not necessarily representative, but the widest approach to sampling a variety of people was used to help represent as many as possible. The questionnaire was distributed to 380 employees of Chinese family firms, with two screening questions validating participants. These questions included: “Is your company a family business?” and “Are your family’s ancestors from China?”

Data was analysed in SPSS, using a combination of descriptive statistics for trend analysis and multiple regression analysis to identify internal relationships between predictor and outcome variables (Keith, 2015).

Qualitative Study

The qualitative research used semi structured interviews with the owners or managers of Chinese family firms (n = 5) as the basis for data collection. These respondents were selected purposely to ensure adequate coverage (Merriam, 2009). Initial respondents were selected from the researchers’ acquaintances, and the sample was then widened to include recommended participants from the initial participants. Face to face, semi structured interviews were recorded and then transcribed for analysis using a combination of content analysis and thematic analysis. These approaches were used to identify the general beliefs about the identified factors and explain how these factors affected business performance.

Findings and Analysis

Survey Findings

Firm and respondent characteristics

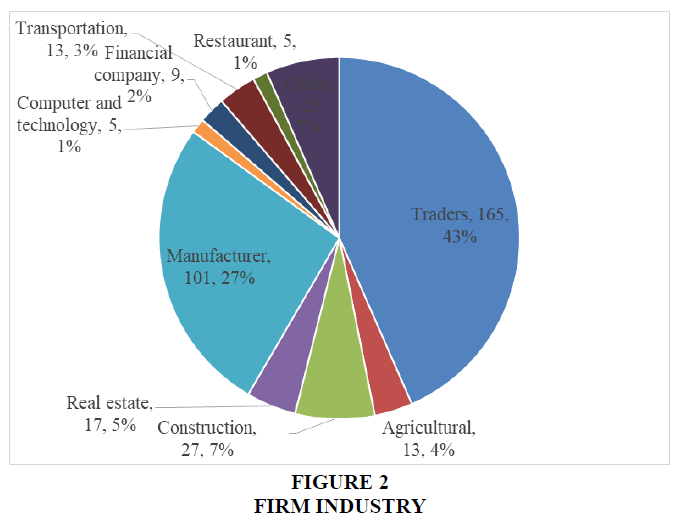

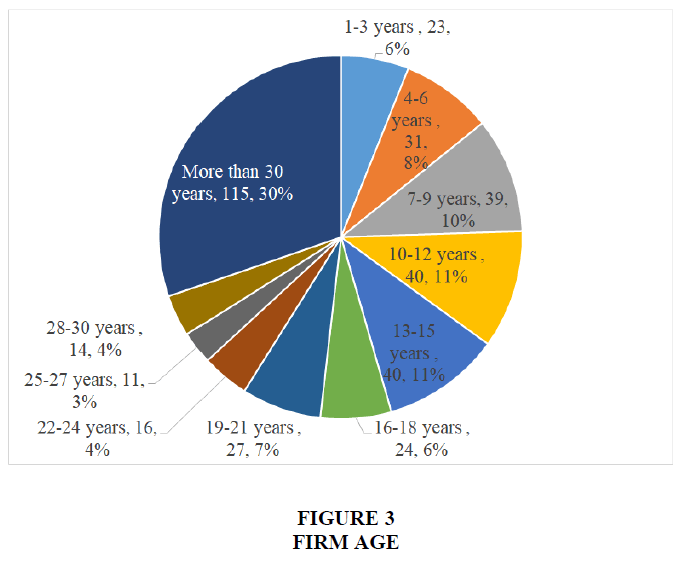

Most of the respondents worked for retail and trading firms (43%) or manufacturing firms (27%) (Figure 2). About 30% of the firms had been in business for more than 30 years (Figure 3). Most of the firms were small firms (up to 50 employees) (69.3%), although the largest group had income of more than 50 million baht/year (30%) (Table 2). The organisational structure of most companies was flat (79.5%). Flat organisational structures meant that there were no layers of management between front-line employees and the top managers of the firm, rather than multiple layers of management (Robbins & Judge, 2013). The flat organisational structure is commonly used in SMEs, as these firms were, because it is more efficient than a hierarchical structure in a small group (Robbins & Judge, 2013). However, as firms grow they do tend to evolve a hierarchical structure due to a growing and increasingly specialised workforce. Thus, the fact that most companies had a flat organisational structure was expected given that the organisations are relatively small.

| Table 2 Firm Characteristics | ||

| Number (n=380) | Percentage | |

| Number of employees | ||

| 1-50 | 263 | 69.2 |

| 50-200 | 71 | 18.7 |

| More than 200 | 46 | 12.1 |

| Annual income | ||

| Lower than 1 million | 53 | 13.9 |

| 1-5 million | 79 | 20.8 |

| 6-10 million baht | 38 | 10.0 |

| 11-15 million | 25 | 6.6 |

| 16-20 million | 35 | 9.2 |

| 21-25 million baht | 9 | 2.4 |

| 26-30 million | 5 | 1.3 |

| 31-35 million | 5 | 1.3 |

| 36-40 million baht | 10 | 2.6 |

| 41-45 million | 3 | .8 |

| 46-50 million | 4 | 1.1 |

| More than 50 million | 114 | 30.0 |

| Company structure | ||

| Flat structure | 302 | 79.5 |

| Hierarchical structure | 78 | 20.5 |

Most of the respondents worked in management (59.2%). They were predominantly male (65.3%), and although ages varied, the largest group was aged 41 to 50 years (30.3%), with more than 10 years’ work experience (87.1%). A general bachelor’s degree was most common (46.1%). Most respondents had Chinese ancestry from one, two, three or more generations previously, but were not themselves born in China. This is consistent with the historic fall in immigration due to international and national policies since the 1980s.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics of the guanxi, renqing and Confucian values scales are shown in Table 4. As this shows, the Confucian values scale scored the highest (M = 4.29, S.D. = 0.716), followed by Renqing (M = 4.12, S.D. = 0.650) and Guanxi (M = 4.09, S.D. = 0.745) (Table 3). These variables are all measured using a five-point Likert scale, which indicates that on average, respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the businesses displayed values of guanxi, renqing and Confucian values in their operations.

| Table 3 Respondent Characteristics | ||

| Number (n=380) | Percentage | |

| Work Role | ||

| Management | 225 | 59.2 |

| Marketing | 21 | 5.5 |

| Accountant | 82 | 21.6 |

| Operation | 52 | 13.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 248 | 65.3 |

| Female | 132 | 34.7 |

| Age | ||

| 20-30 years | 23 | 6.1 |

| 31-40 years | 98 | 25.8 |

| 41-50 years | 115 | 30.3 |

| 51-60 years | 84 | 22.1 |

| 61-70 years | 38 | 10.0 |

| Above 70 years | 22 | 5.8 |

| Education Background | ||

| Primary school | 21 | 5.5 |

| Junior high school | 18 | 4.7 |

| High school or college | 66 | 17.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 175 | 46.1 |

| Master’s degree | 97 | 25.5 |

| PhD degree | 3 | .8 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 76 | 20.0 |

| Married with child | 273 | 71.8 |

| Married without child | 31 | 8.2 |

| Your Work Experience | ||

| 1-3 years | 2 | .5 |

| 4-6 years | 18 | 4.7 |

| 7-9 years | 29 | 7.6 |

| More than 10 years | 331 | 87.1 |

| Any member in your family was born in China? | ||

| Yourself | 17 | 4.5 |

| Father or Mother | 111 | 29.2 |

| Grandfather or grandmother | 189 | 49.7 |

| Great grandparent | 39 | 10.3 |

| Any ancestor before great grandparent | 24 | 6.3 |

| Table 4 Descriptive Statistics | ||

| Guanxi | Mean | S.D. |

| 1. Establishment and maintenance of relationships both at an individual level and a firm level is very important. | 4.44 | 0.603 |

| 2. In your company, exchange of favors and information is often seen. | 4.26 | 0.668 |

| 3. Your leader often gives you a gift on a special occasion. | 3.37 | 1.091 |

| 4. You are always concerned for feelings of other members of your company. | 4.33 | 0.661 |

| 5. You can trust people in your company. | 4.03 | 0.700 |

| Scale average | 4.09 | 0.745 |

| Renqing | Mean | S.D. |

| 1. In your company, giving back to others is very important. | 3.92 | 0.745 |

| 2. Your leader always assists you on work-related problems and you always help him/her back. | 4.18 | 0.631 |

| 3. Your leader usually cares about problems in your society. | 3.93 | 0.719 |

| 4. You are always concerned with other’s feelings. | 4.22 | 0.574 |

| 5. You usually exchange favors with other members of the company. | 4.23 | 0.597 |

| 6. It is your obligation to help other members of the company who are in trouble. | 4.24 | 0.635 |

| Scale Average | 4.12 | 0.650 |

| Confucian Values | Mean | S.D. |

| 1. Your family interest always comes first. | 4.17 | 0.880 |

| 2. Family role is of great importance in your working environment. | 4.15 | 0.853 |

| 3. Your leader always makes the decision based on right and wrong. | 4.12 | 0.746 |

| 4. You have an honest and kind leader. | 4.48 | 0.565 |

| 5. In your company, relationships among others are very important. | 4.37 | 0.610 |

| 6. In your company, you normally work together to achieve goals. | 4.43 | 0.640 |

| Scale average | 4.29 | 0.716 |

Hypotheses 1 & 2

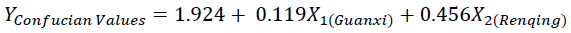

Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested together (Table 4). The model was significant (F = 81.933, p <.001), but only moderately predictive (adj. R2= .299). Coefficients show that both guanxi and renqing are factors in Confucian values. The regression equation is therefore:

Hypotheses 1 and 2 could therefore be accepted. Both of these practices contributed to Confucian values, although renqing had a much higher association with Confucian values than guanxi (Table 5).

Hypotheses 3 through 5

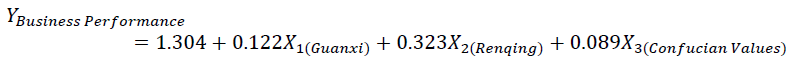

Hypotheses 3 through 5 were also tested in a single regression test (Table 5). The ANOVA test did confirm significance (F = 17.673, p <.001), but the model summary indicated that the model was only weakly predictive (adj. R2 = .117). The coefficient t tests show that only renqing contributed to firm performance, while guanxi and Confucian values were not significant. The regression equation for this model is:

| Table 5 Hypotheses 1-2 Regression Test; Confucian Values as the Dependent Variable | |||||

| M | t | Sig. | |||

| Coefficient | Std. Error | ||||

| Constant | 1.924 | .186 | 10.327 | .000 | |

| Guanxi | .119 | .056 | 2.118 | .035 | |

| Renqing | .456 | .062 | 7.326 | .000 | |

| Adjusted R2: 0.299 | |||||

While Hypothesis 4 can be accepted, Hypotheses 3 and 5 must be rejected. Therefore, renqing is the main cluster of cultural values that was found to be significant for business performance (Table 6).

| Table 6 Hypotheses 3-5 Regression Test; Confucian Values as the Dependent Variable | |||||

| t | Sig. | ||||

| Coefficient | Std. Error | ||||

| Constant | 1.304 | .323 | 4.036 | .000 | |

| Guanxi | .122 | .086 | 1.408 | .160 | |

| Renqing | .323 | .102 | 3.176 | .002 | |

| Confucian | .089 | .079 | 1.129 | .260 | |

| Adjusted R2: 0.117 | |||||

The Managerial Perspective

The three themes identified from the managerial perspective included guanxi and renqing in the family firm and the broader role of Confucian values.

Guanxi in the family firm

Key expressions of guanxi in the family firm included compromising to avoid conflict and preserve harmony, building and developing social networks, and the exchange of favours. Respondents had a generally positive view of these practices, noting that they helped to ensure that the firm operated harmoniously and that they did not act against the interests of the firm. Network relationships with suppliers, customers, and communities were viewed as particularly important for firm performance. However, there were some acknowledged problems, including the potential for corruption and the need to balance harmony and action in areas important to the firm. For example,

One participant stated:

No, wrong should be wrong. We need to consider based on what is right and wrong first, before we start to compromise. Compromising can lead to corruption at all times… But with partners, suppliers or customers, compromising is a good way to do business. It lets us reach a win-win solution.

Another participant stated:

I do agree since doing business in industrial products has a big gap to use this values as the way to corruption. But our company has strictly investigating system since we are about entry stock market.

Thus, there was some conflict about the use of guanxi and its potential effect on corruption. At the same time, participants were not willing to bring up the potential negative effects that could result from this action. Disagreement or challenging participants, rather than appearing to agree, could be viewed as disrupting harmony and hierarchy. Thus, this type of direct action was not usually viewed positively by the participants. At the same time, the participants pointed out that the companies had codes of conduct in place that were intended to prevent these occurrences and/or investigate them when they did occur. This type of investigation was viewed as a restoration of harmony or balance when negative actions disturbed it. Therefore, harmony is a more complex issue than just disagreement, but there was the potential that corruption could go unchallenged if there was not enough will to challenge it or if there were not organisational structures in place for it.

Renqing in the Family Firm

Renqing was mainly viewed as collaborative, cooperative and helping behaviours that occurred within the firm. Reciprocal exchange of gifts and favours was commonplace both within the firm’s boundaries and outside the firm, and occurred at all levels. While it was acknowledged that this had an economic aspect, it was not mainly transactional, but was instead viewed as an expression of family feeling between the members of the firm (even where there were inequalities in the relationships between individuals). Renqing also is not inclusive, and may not include new members of the firm, those who work remotely or otherwise avoid personal relationships, or who are perceived as having transactional relationships (only wanting money). Renqing and its associated relationships was strongly associated with deeply personal relationships and support within the firm, contributing to the formation of trust and social capital. Thus, while this did not have a direct impact on the firm’s economic performance, it was viewed as one of the factors in making the firm a good place to work.

The Broader Role of Confucian Values

Respondents recognised and expressed support for general Confucian values within the firm, including the strong role of family, leadership honesty, and the importance of teamwork and integrity. At the same time, respondents were not completely uncritical, recognising the potential for corrupt leadership and inequality within the organization. Respondents also acknowledged that conflict avoidance could have a negative effect on the organisation, with surface harmony being disturbed by deeper resentment and problems such as nepotism. Thus, Confucian values played a complex role in the organization, which was generally but not completely considered positive.

Discussion

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of the findings is that while both quantitative and qualitative studies showed awareness of guanxi, renqing, and the broader set of Confucian values in the firm, they did not directly support a strong role of these value sets in the performance of the business. In part, this may be because of the limited perspective that Western business literature has on business performance itself, which is focused on productivity (whether economic or in terms of return to stakeholders or internal efficiency) (Lebas & Euske, 2004). In contrast, the interviews revealed that the managers of the firms studied were more concerned with whether their firms were a good place to work for employees and how the identified values contributed to this improvement. This is in part due to the nature of the family firm, where owners may hold specific priorities that are not necessarily related directly to economic performance (Tokarcyzk, et al., 2007). However, the role of renqing, in which concern for human feeling is paramount rather than economic profit, can also be seen here. This research supports the idea that renqing, often relegated to a rural past (Chan, 2006), is in fact part of dynamic business processes like cooperation within and between firms.

The close relationships formed between leaders and followers also could create competitive advantage through trust and social capital (Ramos, 2016). This is also true of the use of guanxi, in which networks of social connections are built not just for the firm’s immediate needs but for the long term. The nature and value of guanxi relationships may not be apparent to the participants, particularly if they are unconsciously relying on relationships that were established in the past. This research does support the importance of guanxi for the business, even if it was not found to directly contribute to the firm’s performance.

Finally, there is the question of the broader role of Confucian values in the firm. This question cannot be answered directly from the literature, because of the cultural differences associated with these values in different Chinese ethnic groups (Tu, 2008). This research showed that the relationship is complicated, and cannot be considered either wholly positive or entirely negative. Thus, as with any set of cultural values (Hofstede, et al, 2010), the effect of Confucian values is complex and over determined.

Conclusion

This research set out to investigate what effect, if any, Confucian values of Thai Chinese family firms would have on the business’s performance. The findings showed that members of family firms did perceive cultural norms including guanxi and renqing at work within their organisations, and did consider that these norms were associated with a broader set of Confucian values, including leadership integrity, trust, and harmony among others. However, the study did not show that these values were strongly associated with perceived business performance. Only renqing could be associated directly with business performance in the quantitative research, although the interviews suggested that cooperation and concern for others contributed both to the firm’s effectiveness and of making it a better place to work. As with any set of cultural values, there was also a dark side to Confucian values, although respondents did not consider corruption, nepotism or conflict avoidance to be serious concerns. Thus, these Confucian values were clearly a positive for the company, even if they do not contribute directly to economic performance.

This research is mainly limited in that it did not compare Thai Chinese firms to other family owned firms or to Chinese family firms in other host countries, which could help to determine the extent to which the values identified and their relationships were unique to Thai Chinese firms. This could be a significant benefit to the literature, since it could help resolve conflicts and help determine how unusual Confucian values are, and the extent to which they change to meet local cultural norms. Thus, this is an area that should be considered for future research.

References

- Apisakkul, A. (2015). A comparison of family and non-family business growth in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. UTCC International Journal of Business and Economics, 7(4), 63-75.

- Baker, B., & Phongpaichit, P. (2014). A history of Thailand (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Banalieva, E.R., Eddleston, K.A., & Zellweger, T.M. (2015). When do family firms have an advantage in transitioning economies? Toward a dynamic institution-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 36, 1358-1377.

- Chan, A.M. (2006). The Chinese concepts of guanxi, mianzi, renqing and bao: Their interrelationships and implications for international business. Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference. Brisbane, Australia.

- Chen, X., & Chen, C.C. (2004). On the intricacies of the Chinese guanxi: A process model of guanxi development. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 21, 305-324.

- Chen, X., & Peng, S. (2008). Guanxi dynamics: Shifts in the closeness of ties between Chinese coworkers. Management and Organization Review, 4(1), 63-80.

- Connelly, J.T. (2016). Investment policy at family firms: Evidence from Thailand. Journal of Economics and Business, 83, 91-122.

- Dinh, T.Q., & Calabró, A. (2019). Asian family firms through corporate governance and institutions: A systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21, 50-75.

- Fullerton, R.R., & Wempe, W.F. (2009). Lean manufacturing, non-financial performance measures, and financial performance . International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 29(3), 214-240.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G.J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). London: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Ip, P. (2009). Is confucianism good for busienss ethics in China? Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 463-476.

- Keith, T.Z. (2015). Multiple regression and beyond: An introduction to multiple regression and structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Lebas, M., & Euske, K. (2004). A conceptual and operational delineation of performance. In A. Neely (Ed.), Business performance measurement: theory and practice (pp. 65-79). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- LePoer, L.L. (1987). Thailand: A country study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

- Li, Y., & Kell'i Akina, W. (2014). The role of classical Confucian philosophy in the development of Chinese business ethics.

- Low, K.C. (2010). Values make a leader-the Confucian perspective. Insights to a Changing World, 2, 13-28.

- Merriam, S.B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and interpretation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Ordóñez d Pablos, P., & Lytras, M.D. (2010). The China information technology handbook. New York: Springer.

- Paladino, B. (2011). Innovative corporate performance management. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

- Pananond, P. (2007). The changing dynamics of Thai multinationals after the Asian economic crisis. Journal of International Management, 13, 356-375.

- Peteron, R.A., & Kim, Y. (2013). On the relationship between coefficient alpha and composite reliability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 194-198.

- Poutziouris, P., Wang, Y., & Chan, S. (2002).  Chinese entrepreneurship: the development of small family firms in China . Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 9(4), 383-399.

- Ramos, H.M. (2016). The influence of family ownership and involvement on Chinese family firm performance: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Management Practice, 9(4), 365-393.

- Robbins, S.P., & Judge, T. (2013). Organizational behavior (14th ed.). New York: Prentice Hall.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students (5th ed.). London: Pearson Education.

- Soleimanof, S., Rutherford, M.W., & Webb, J.W. (2018). The intersection of family firms and institutional contexts: A review and agenda for future research. Family Business Review, 31(1), 32-53.

- Sternad, D., & Kennelly, J.J. (2017). The sustainable executive: Antecedents of managerial long-term orientation. Journal of Global Responsibility, 8(2), 179-195.

- Tokarcyzk, J., Hansen, E., Green, M., & Down, J. (2007). A resource-based view and market orientation theory examination of the role of "familiness" in family business success. Family Business Review, 20(1), 17-31.

- Tu, W. (2008). The rise of Industrial East Asia: The role of Confucian values. The Copenhagen Journal of East Asian Studies, 4(1), 81-97.

- Walker, E., & Brown, A. (2004). What success factors are important to small business owners? International Small Business Journal, 22(6), 577-594.

- Woods, P.R., & Lamond, D.A. (2011). What would Confucius do? - Confucian ethics and self-regulation in management. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 669-683.

- Xu, S. (2012). Trust in relational leadership: reciprocity or renqing. A study on the flow of gift-giving in China’s private and foreign firms .

- Yabushita, N.W., & Suehiro, A. (2014). Family business groups in Thailand: Coping with management critical points. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(4), 997-1018.