Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

Dark Side of Value Co-creation Strategies

Diana Escandon-Barbosa, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Cali

Jairo Salas-Paramo, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Cali

Geovanny Castro, Universidad Autónoma De Bucaramanga

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this research is to identify the saturation effects of the consumer company identification, involvement and value co-creation in the fashion and car industry in Colombia.

Design/methodology/approach: It has been defined to use the method of quadratic structural equations allowing analyzing the behavior of variables in a non-linear way, maintaining the advantages of structural equation models. To reach the objective has been collected a survey of 400 consumers from the Fashion and Automotive sectors in Colombia who have participated in value co-creation processes has been carried out.

Findings: The results show that consumer involvement has a maximum level of influence on consumer company identification, from which the benefits begin to decrease for both the fashion and automotive sectors. In the case of the value co-creation, it also shows that it has a maximum level in which its implementation has benefits on the consumer company identification. Research limitations/implications: Within the limitations, it can be found that the information used describes particularities of a country considered in the process of development where its cultural characteristics can affect the perceptions of consumers. Practical implications: Most companies generate strategies that allow them to improve relationships with their consumers through collaborative processes that allow them to add value to their processes and products. However, such strategies have decreasing behaviors over time that generate less benefit both in their performance and in their relationships with their clients. In this way, companies will have evidence of the need to establish temporary plans in which a strategy will generate greater benefits.

Social implications: The results of the research allow us to understand the individual and social characteristics that are fundamental for the implementation of strategies aimed at including the consumer in the design processes to create value for the company.

Originality/value: Most of the literature in the field of the Service dominant logic has focused on empirical studies that show the benefits of the implementation of value co-creation. However, it is possible to find studies in which the possibility of finding results in processes of value co-creation unsatisfactory for both companies and for the consumer is considered. It is precisely in the negative results that the present study has defined as the main purpose of the research.

Keywords:

Value Cocreation, Consumer Company Identification, Consumer Involvement. Quadratic Structural Model Equation, Co-Destruction, Saturation Effects

Introduction

Much of the strategy literature indicates that success in strategy implementation is extremely low. In most of the research in the field, is possible to find that the range of failures in the strategy oscillates between 7% and 90% with an average of 50% (Forbes, 2019; Candido & Santos, 2015). Additionally, the improvements in its execution are not satisfactory over time and even the initiatives to counteract the situations repeatedly fail. On the other hand, about innovation strategies, the failure rate is around 50%, there is even evidence that many times they fail not only because of ineffective investments but that they can also affect future performance in the long-term (Castellion & Markham, 2013; Hess, 2009; Bayus et al., 2003). Faced with this, some authors argue that a large part of the failures is due to the behavior of individuals since, as consumers, they develop a resistance that induces failures (Ellen, Bearden & Sharma, 1991; Ram, 1987; Reinders, 2010; Talke & Heidenreich, 2014).

It is precisely where the relationship between company and consumer becomes fundamental to be able to face the dynamics of the company's markets. According to the theory of social identity, individuals develop significant emotional ties to the membership of the groups they belong (Tajfel, 1978). In this way, through belonging to groups, individuals develop behaviors that are favorable to the organization (Ashforth, Harrison & Corley, 2008). This relationship is based on the argument that the consumer's values fit to the company values. The above is defined consumer company identification.

The Social Identity Theory assumes that consumers develop self-concepts based on knowledge, values and emotions that are linked to the social groups to which they belong. According to above consumers will feel an active part, accepting not only their values but also their beliefs that give significance between individual and company objectives (Ali, Ali, Grigore, Molesworth & Jin, 2020; Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Van Knippenberg & Sleebos, 2006; Corley, Harquail, Pratt, Glynn, Fiol & Hatch (2006).

In this way, the consumer company identification is defined as the degree to which consumers feel the sense of connection with the company and which in turn serves as a self-reference to define themselves (Einwiller, Fedorikhin, Johnson & Kamins, 2006). According to Zhang & Kim (2016). Similarly, consumer company identification is considered as a process in which the consumer is integrated to the company with the intention of making their constructive participation in the creation of a service (Auh, Bell, McLeod & Shih, 2007). This also includes the delivery of a process or set of activities that are made up of their contributions. According to the above, the value co-creation becomes a central element of the commercial activities of companies in such a way that it becomes a proposal of the firm to improve the consumer experience (Gentile, Spiller & Noci, 2007; Volchek, Law, Buhalis & Song, 2020).

Value co-creation has been one of the perspectives that has paid great attention among researchers because it tries to integrate consumers into the value creation processes of companies (Rui & Kai, 2021). Lot of research in value co-creation have focused on the field of Tourism, e-commerce, Health, Fin tech, Branding, Industries 4.0. (Tram-Anh, Sweeney & Soutar, 2020; Bourne, 2020; Benitez, Ayala & Frank 2020; Rezaei, Watson, Cliff & Miah, 2020).

In the development of the field of value co-creation it is possible to identify two lines of development. One is that of Prahalad and Ramaswamy who rely on their approaches from the theory of competition. On the other side is the current proposed by Vargo and Lush from the perspective of service dominant logic. In the case of Prahalad and Ramaswamy, the center of their analysis focuses on the relationship with consumers through consumer experiences. While for their part, Vargo and Lush focus on the value of use. This perspective establishes that consumers create value in the integration and use of the reviews during the consumption of the products (Rui & Kai, 2021).

According to the above, SDL proposes that consumer participation in the processes to add value to companies through design and the generation of ideas can provide valuable information for innovative processes (Ye & Kankanhalli, 2020). It is important to note that some authors have reported a variety of results in consumer participation. On the one hand, positive results are found insofar as the inclusion of the consumer has effects on the profitability of the firm (Ordanini & Parasuraman, 2011; Schaarschmidt, Walsh & Evanschitzky, 2018). On the other hand, investigations such as those of Carbonell, Rodriguez-Escudero & Pujari (2009); Chen, Tsou & Huang (2009), found no influence on the performance of the firm.

Despite to the variety of results, value co-creation implies an active participation in the set of activities of the company by the consumer, its inclusion in the processes tends to become in a central aspect. Active participation is the key to this type of strategy that allows companies to capitalize on the effort to be able to satisfy the needs of consumers. Therefore, involving the consumer in the value co-creation process is considered a business strategy to improve levels of innovation because they are a source of information and creativity (Sjodin & Kristensson, 2012; Kristensson, Matthing & Johansson, 2008). According to the theory, the success of the co-creation process depends on the correct selection of the participants who will support all stages of product creation. This new strategy to integrate the consumer breaks with the paradigm of innovation and creation, where the effectiveness of the product is evaluated through the acceptance of the consumer.

It is recognized that the inclusion of the consumer in the company's processes does not always turn out to be as expected (Dong, Evans & Zou, 2008; Echeverri & Skålén, 2011; Plé & Cáceres, 2010; Edvardsson et al., 2011; Grönroos, 2011). These dynamics have tried to be theorized since, during this type of process, company employees can be exposed to conflicts which can trigger negative conditions (Edvardsson et al., 2011). Additionally, negative behaviors may occur on the part of the consumer that may affect the performance of the firm (Ertimur & Venkatesh, 2010). Despite the above, there are very few empirical studies that shed light on this type of dynamics (Chowdhury, Gruber & Zolkiewski, 2016).

In reviewing the literature in the field of value co-creation it is possible to find few studies on the dark side of this process. The dark side is understood as those aspects that are not evident in the implementation of value co-creation that have negative impact on the performance of the company. In the same way, it considers the potential risks of products in the market, for example, service failures and especially in the use of technological platforms (Heidenreich et al., 2014).

It is also possible to observe that positive results are always expected from the implementation of this type of strategy (Plé & Cáceres, 2010; Lindgreen et al., 2012). According to Vargo & Lusch (2004; 2008), these dynamics where the consumer is integrated into the internal processes of the companies have immersive dynamics of interaction between different actors and resources. It is precisely in these dynamics that ideal conditions for instability, conflict and confusion can be found. Research in the field of the dark side shows another concept linked to negative experiences of the service called co-destruction. This concept is defined as a condition in which the company's resources are misused, either by accident or intentional (Plé & Cáceres (2010). Thus, despite the few studies focused on studying this type of phenomenon in business-to-consumer relationships, there is also a need to study business-to-business relationships. Unfortunately, these areas have been characterized by being omitted from the main lines of discussion of studies in the field (Grönroos & Voima, 2013; Payne et al., 2008; Ramaswamy & Gouillart, 2010).

It is important to point out that the literature in the field not only of the theory of social identity but also in that of the value co-creation as well as that of consumer involvement and consumer company identification has focused in a particular way on positive aspects of the results found. However, there is little research that focuses on the non-positive findings of the implementation of this type of strategies. This research focuses in this theoretical and empirical gap that makes mandatory to ask the question about how sustainable these types of strategies are over time. Additionally, what makes to the consumer an active participant considering that the influence both individuals and social aspects in their contributions to co-creation activities.

A gap found in the literature is the need to carry out more in-depth studies in different contexts of the dynamics in which value creation strategies fail (Castillo, Canhoto & Said, 2020). Since the studies have been qualitative in nature, it has not yet been possible to make possible generalizations in similar contexts such as industries or comparative ones between them. According to the above, this study contributes not only to a more in-depth analysis of the negative dynamics of value co-creation but also to deepen its operationalization in industrial sectors of great importance such as fashion and car. This is how the present research aims to identify the quadratic effects of the consumer company identification, involvement and value co-creation in the fashion and Car industry in Colombia.

Theoretical Framework

Value Co-destruction Perspective: Saturation Effects of Value Co-Creation, Involvement and Consumer Company Identification

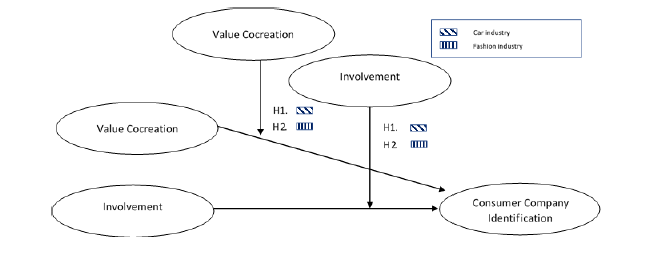

To evaluate the possibility that the relationships between value co-creation, involvement and consumer company identification always generate positive results or, on the contrary, if there is an inflection point where value co-creation becomes an inappropriate strategy to achieve consumer company identification, four alternative hypotheses have been proposed.

Authors such as Day, Grabicke, Schaetzle & Staubach (1981); Braunsberger & Buckler (2011); Klein, Gabrielle, Smith & John (2004); Freestone & Mitchell (2004); Baron & Harris (2008); Wirtz & Mc Coll Kennedy (2010) have investigated the possibility that when implementing value co-creation processes the results will not always be satisfactory. This proposition has been supported by Gebauer (2013), who focuses on the negative results in the interaction of individuals for innovation processes due to the complexity of the relationships and the perceptions that individuals develop in the group. According to the above, value co-creation and consumer company identification will have an optimum point in which a subsequent investment of resources in this strategy would not produce the expected results.

Within the set of dysfunctional behaviors, it is possible to find complaints (Day et al., 1981), boycott of certain brands (Braunsberger & Buckler, 2011; Klein, Gabrielle, Smith & John, 2004), forms of fraud (Freestone & Mitchell, 2004, Baron & Harris, (2008), opportunistic behavior (Wirtz & McCollKennedy, 2010) and physical and verbal abuse towards company employees (Keashly & Neuman, 2008). in negative perceptions towards the brand, stress and job dissatisfaction that affects employees, damages the financial structure of the company, and worsens the reputation (Fisk et al., 2010).

However, this dysfunctional behavior that somehow leads to a decline in overall well-being, results in an unexpected loss of valuable resources for the company (Smith, 2013). When a consumer expects to use a product, he expects to have a satisfactory user experience. However, when he obtains the opposite, this can trigger emotions of frustration (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2018).

Considering the previous, the consumer experiences frustration and loss of time, a condition that has been defined as value co-destruction. This is defined as a perception where a consumer in his product experiences feels more loss than gain. The literature in this field defines co-destruction as a set of factors that serve as antecedents of loss of value. These factors are based on the loss of time as a valuable resource and the lack of information, indifference, errors and technical failures, consumer company identification and involvement (Järvi et al., 2018; Zhang, Lu, Torres & Chen, 2018; Robertson, Polonsky & McQuilken, 2014).

Consumer involvement is one of the characteristic behaviors of people who commit themselves to a product based on positive actions, comments that allow them to obtain information (Seelig & Rosof, 2001; Algesheimer, Dholakia & Herrmann, 2005). However, in the literature it is possible to find that, despite the beneficial results, it is possible to unleash a series of irrational behaviors and with consequences for organizations. In this way, the involvement is usually displayed with the willingness to pay for a product. An example is a response to the confidence that a consumer develops for the information he has of a company or a product (Seelig & Rosof, 2001; Algesheimer, Dholakia & Herrmann, 2005).

A highly involved behavior causes that consumer do not measure the level of resources invested to increase his Company identification. However, he will expect the company not to defraud him with the quality of the product (Fisk et al., 2010). Regarding value creation activities, a company will try to improve the intensity of the relationships with its consumers involved through messages and comments. At the same time, trying that value creation activities allowing a strong identification and a sense of community (Algesheimer, Dholakia & Herrmann, 2005).

However, if such interactions with these consumers trigger reactions of dissatisfaction with product quality, the company could direct contingency actions that allow to overcome the perceptions of dissatisfaction. At the same time, could start actions to improve relations in terms of their interaction and commitment with consumer (Algesheimer et al., 2005). Finally, if the companies do not take actions to offset dissatisfaction, it is possible that the level of involvement diminishes from the consumer.

Authors such as Roser (1990); Algesheimer, Dholakia & Herrmann (2005) state that there may be other options for response by consumers to the company in the face of service failures. If the involvement is positive, the consumer will be motivated to resist negative communications and their attitude will not change, despite the existence of messages against the company. However, when the involvement is negative, the individual may be easier to persuade to change their behavior in any direction. Therefore, the results of their behavior would show a negative effect against Identification with the Company (Roser, 1990).

According to the literature, the relationship with the Identification with the Company can be negative depending on the size of the impact of the consumer involvement on a particular event (Hamzelu, Gohary, Nia & Heidarzadeh, 2017). For Vaughn (1980, 1986), there are four conditions applied to the fields of psychology, social economy and behavior, in which Consumer involvement can present change: a. When the involvement is high, people decide their purchase based on rational thinking, examples of this are the purchase of products such as houses, cars and clothes. b. When the involvement is high, consumers decide their purchase based on emotions, examples of this are jewelry and cosmetics. c. When the involvement is low, individuals buy rationally products such as food and basic need. Finally, d. In the case of low involvement when individuals buy emotionally, evaluating their emotions for the purchase of products such as cigarettes and drinks.

Considering the above, in the case of the Car industry, the level of involvement with the company tends to be higher due to the number of resources invested. Therefore, the purchase of Car complies with the conditions of high levels of involvement of a product and an inflection is expected if its level of company Identification is affected.

The consumer company identification will have a relative impact in the consumer involvement with similar behaviors patterns in different products categories (Kwon, Ha & Kowal, 2017). Additionally, to the above, the involvement that an individual has will vary according to the type of personal characteristics (Alonso-Dos-Santos, Vveinhardt & Calabuig-Moreno, 2016). This type of behavior is expected due to the existence of high volumes of involvement associated with the amount invested in cars and which may cause that the levels of identification decreasing. These high levels of involvement make expectations are difficult to accept and enforceable by the company. While, in the Fashion industry, the involvement will not be so strong because the amounts and resources invested are not so high. Additionally, that the average duration of a garment has a shorter life span than in the Car industry. These low levels of useful life of the products for Fashion industry make that a bad product is replaced with greater facility and the levels of involvement are lower than other industries.

H1: The relationship between involvement and consumer company identification shows stronger saturation effects for the car industry than in the Fashion

Considering the characteristics of the Car industry, both in amounts of resources invested and in the frequency of purchase, they make possible the existence of higher levels of involvement. However, being more sensitive to the service that can be received by the involvement level gives the possibility of finding saturation effects when it comes to Identification with the Company. In Fashion industry, although apparently the levels of involvement may be lower than in Car, it can be assumed that some consumers do need to be involved. Above due to the variety of brands, the existence of different levels of capital invested and the high frequency of purchase. Therefore, the purchase of products in this industry will be characterized by having consumers with different levels of information. However, due to the type of characteristics of the industry in Colombia, it is noted that the purchase frequency is every six months (Inexmoda, 2018), assuming a purchasing dynamic that will make consumers constantly evaluate their level of identification with the Company.

Additionally, in the Colombian market it is highlighted that there are different levels of costs of the garments and levels of involvement. However, those that invest more resources will be more involved being more critical and showing greater sensitivity to any inconvenience with the product (Blazquéz, 2014). According to the above, it is expected that there is a turning point where the level of involvement stops affecting positively the Company Identification and begins to generate negative effects. The negative effects appear due to the higher expectations of consumers in the Fashion industry when there are high levels of involvement (Blazquéz, 2014). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: The relationship between involvement and consumer company identification shows stronger saturation effects for the Fashion than for the Car industry.

Much of the literature in the field of consumer behavior and earlier in psychology have begun to show particular interest in nonlinear relationships in Co-creation processes and their effects on satisfaction, loyalty and consumer company identification. (Stokburger-Sauer, Scholl-Grissemann, Teichmann, Wetzels, 2016; Franke, Schreier, & Kaiser, 2010; Homburg & Kühnl, 2014; Heidenreich, Wittkowski, Handrich & Falk, 2014; Mahr, Lievens & Blazevic, 2014).

Other studies have found limitations in the provision of services because the fact that they have found relationships in the form of an inverted U (Homburg et al., 2014). Other studies indicate that companies need to undertake processes for a deeper understanding of the conditions from which consumers wish to invest greater knowledge, skills to develop Co-creation processes (Mahr, Lievens & Blazevic, 2014). On the other hand, studies such as that of Franke, et al., (2010), suggest that the contribution that consumers make could be modeled in the form of an inverted U. The above because at high levels of contribution by the consumer there will be a moment in which the process will not be a beneficial experience.

Participation in Co-creation processes is associated with different temperamental and personality dispositions, as well as socialization experiences (Gebauer, 2013). Additionally, several categories of this behavior may be associated with different outcomes in certain contexts. Sometimes Co-creation can be associated with helping others or benefits towards oneself (Füller, Bartl, Ernst & Mühlbacher, 2006; Romero & Molina, 2011).

Excessive help behavior can lead to excessive guilt, anxiety and feeling of temporary failure, if the individual feels that their ideas were not taken into account. Another example of a problem associated with value co-creation occurs when it exceeds the help to others because there are elements of inhibition, emotional instability or feeling. These feelings are an essential part of the organization, which is encouraged by the recurrent requests from the organization to collaborate in its processes (O'Connor, Dollinger, Kennedy & Pelletier-Smetko, 1979; Füller, Bartl, Ernst & Mühlbacher, 2006; Romero & Molina, 2011).

On the other hand, the positive effect of co-creation on Identification is subordinated to the set of values that the individual possesses. Some studies have shown that, to the extent that these values lead to an ethical obligation, their concern for the welfare of others will be greater and, therefore, their effects on identification (Gebauer, 2013). However, they can trigger negative effects when this help is extended to the company for a prolonged period of time. At the same time, when its proposals are not visualized in the development of new products (Ajzen, Rosenthal & Brown, 2000).

Co-creation in the Colombian context is highly plausible because it is a society culturally prone to collaboration (Fenalco, 2018). Additionally, it is expected that, in the case of the Car industry, co-creation may be positive, but that after high levels of collaboration a negative trend is generated. This fact is because the consumer may be prone to collaborate in co-creation processes in the company, but over time their behavior can become negative, if the time that has passed in the co-creation process has been very long (Gebauer, 2013). This is especially true in this kind of product where the purchase frequency is over five years in countries such as Colombia (Fenalco, 2018). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: The relationship between co-creation and consumer company identification shows stronger saturation effects for the Car industry than in the Fashion

For its part, the Fashion industry has usually generated co-creation processes in different countries of the world due to its need to make clothes increasingly adapted to its consumers (Gebauer, 2013; Füller, Bartl, Ernst & Mühlbacher, 2006; Romero & Molina, 2011). For the Colombia, value co-creation is expected to be positive, but after a certain level it begins to show negative tendencies. The above because the collaboration processes should not be prolonged due to the possibility of generating apathy in the participants. Likewise, it is expected that due to the great amount of garments that a brand can design, the consumer can begin to lose his company identification if he can not materialize his ideas (Gebauer, 2013). That is, in this type of industry that consumer can assume the role of expert, even above the businessmen. Therefore, will feel valued and ratified in their role to achieve evident results in the new catalog of Fashion products of the company with which you feel identified. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed: as shows in Figure 1.

4: The relationship between value co-creation and consumer company identification shows stronger saturation effects for the Fashion industry than in the Car industry.

Methodology

Sample Description

The information is collected using simple random sampling in the main cities of Colombia (Cali, Bogotá, Barranquilla & Medellín). The technique of gathering information is done through a surveyor to 400 people face-to-face between the months of June to August 2019. The sample consists of 48% men and 52% women, the age range was 18 to 57 years old. The complement information is described in Table 1.

| Table 1 Survey Technical Data Sheet |

||

|---|---|---|

| Fashion | Car | |

| Universe (Population) | Regular consumers of products from the Fashion and vehicles industry in Colombia | |

| Sample Size | 190 Car Consumers | 210 Fashion Consumers |

| Information gathering technique. | Physical survey applied to users of Fashion and vehicle industries by the market research company. | |

| Period of field work | June-august 2019 | |

| Sampling procedure | Random | |

| Software | Stata 14 | |

Therefore, for Colombia we have obtained a representative sample of the sample universe, based on data published by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (www.dane.gov.co), referring to the socio-demographic profile of the respondents as shown in the table 1, evidence a greater participation of the female gender (52%) in the age range 18-25 years (46.4%), single marital status (55.8%).

The participants are explained the objectives of the research and the use that the data will have. At the beginning of each questionnarie (see appendix I and II) a segmentation question is asked to identify the consumers of Car and those of the Fashion industry. Thanks to the information obtained by the market research company, the information obtained had the advantages of questionnaire collection.

Variables Description

The questionnarie is structured from closed, dichotomous and multichotomic questions of simple and multiple response. At the same time, is combined with Likert scales, to obtain information at the level of the variables under study. The survey is divided into different sections where each one focuses on the questions that taking account the measured construct. In addition, questions have been defined that give an account of socio-demographic aspects, as well as specific brands of the type of fashion house and car brand that most frequent for the purchase of products:

Instrumentation of the Variables and Scales of Measurement of the Proposed Acceptance Model

Taking as reference the theoretical framework, the variables selected for the present study are complex and their measurement cannot be done directly. Therefore, it is necessary to proceed with the instrumentation of constructs that are measured from indicators or observable variables.

Measurement of the Latent Variables and Measurement Scales Used

For the collection of information, it was necessary to develop a questionnaire that consisted of a series of general questions about the individual interviewed; Subsequently, measurement scales selected based on the literature reviewed were used. For the questions, a seven-point Likert scale was used, where the ranges vary from 1=Totally disagree to 7=totally agree. The scales used are consumer company identification, value co-creation, involvement. Consumer company identification is defined as a behavior that promotes the commitment between the company and consumers. Additionally, a sense of belonging is highlighted, leading to rejecting negative comments about the company (Marín & Ruiz de Maya, 2007).

Value co-creation is defined as the participation of the consumer in the development of a product, making possible its inclusion in the processes of generation and evaluation of ideas. The value co-creation also allows the opening towards the reception of your needs on how to improve the products offered to the market through the relationships with consumers (Fuller et al., 2010). The involvement is the consumer's motivation to actively participate in the development, improvement or design products offered by a company. In this way, the involvement includes the use of technology and the ability up to its tendency to be at the forefront of market developments of the products (Kim, Haley & Koo, 2009; Zaichkowsky, 1985).

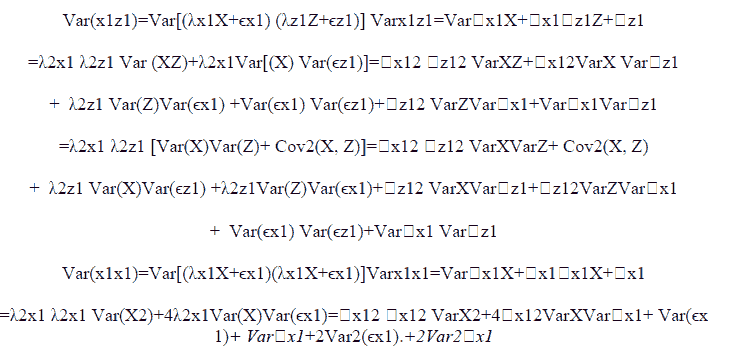

Modeling Multi Group Structural Equations with Nonlinear or Quadratic Effects

Finally, a Multi-group model is made, but with selecting specific variables to establish quadratic or saturation effects. Due to the complexity of the quadratic model and the need to verify the existence of inflection points in the co-creation and the involvement on Identification with the Company it was necessary to use the method proposed by Ping (1996). This methodology states that the calculation of moderating effects (in the case of quadratic effects is a moderating effect of the variable on itself) must be calculated from the combination between the items that make up each latent variable. Therefore, according to Ping (1996), for latent variables X and Z with indicators x1, x2, z1 and z2 a new latent variable XZ must be specified with the combination of the items of the original latent variables as follows: x1z1, x1z2, x2z1 and x2z2. In the case of this research that tries to explain the quadratic effects of the latent variable co-creation and involvement, it is calculated by combining the same items of the latent variable that is, co-creation quadratic is co1 * co1, co1 * co2 co1 * co3, co2 * co3, co3 * co2. In general, the model of quadratic effects under the structural equation methodology is visualized in the following way:

Quadratic Effects Model Results

From the results of the model, it is concluded that the model has good kindness and adjustment. The total and multi-group models are satisfactory (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). The RMSEA is less than 0.05 while the CFI and TLI are equal to 0.9. The results confirm hypotheses 1 and 2 that state that the relationship between involvement and consumer company identification has an inverted U shape for Cars and Fashion Industry. Additionally, hypotheses 3 and 4 are confirmed, the relationship between co-creation and consumer company identification in the form of an inverted U is also confirmed for the two industries. The above can be observed in the Table 2.

| Table 2 Coefficients of the Quadratic Model |

||

|---|---|---|

| Model Relationship (Hypothesis) | Standard Coeficient | t- value |

| H1: Quadratic involvement-consumer company identification Car Industry | -3.01 | 0,01 |

| H2: Quadratic involvement -consumer company identification Fashion Industry | -4,056 | 0,01 |

| H3: Quadratic value co-creation –consumer company identification car industry | -2.012 | 0,05 |

| H4:Consumer company identification fashion industry | -2.34 | 0,04 |

| Adjustment of the multi group model RMSEA: 0,007; CFI: 0,90; TLI: 0,90 | ||

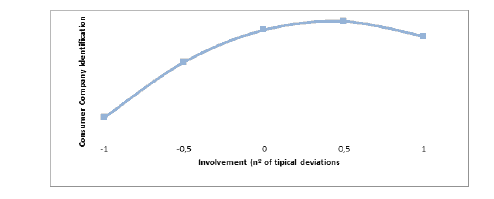

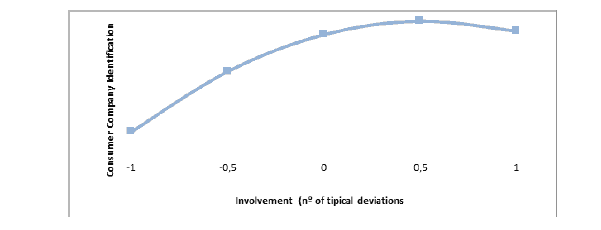

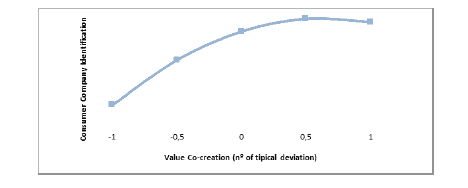

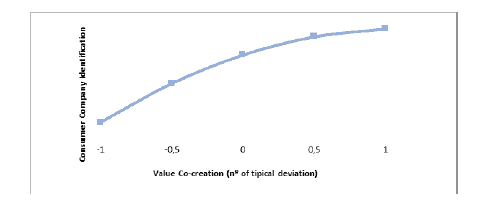

Based on the results obtained and presented in Table 2, Figures 2 and 3 graphically represent the quadratic effects of involvement and co-creation for every industry. In all cases it is shown that these variables have a decreasing positive effect on the consumer company identification. The Y axis represents the values obtained for consumer company identification when different values of the explanatory variable (involvement and co-creation) a function is constructed from the constructs calculated in the multi-group model.

According to Dawson & Richter (2006) this representation is necessary because the results of the multi-group model do not allow to visualize the inflection point in each of the variables. In the X axis the different values given to the variables of involvement and value co-creation are presented. According to Aiken & West (1991), the variables are centered on the mean, the low values of these variables are represented by a value equal to minus a certain number of standard deviations of the variable. For high values, a positive number of standard deviations is used.

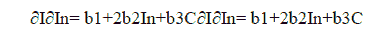

Next, we present the procedure followed to obtain these results, based on what was proposed by Aiken and West (1991). Consumer company identification varies with changes in the involvement following the following function:

It is possible to observe, the effect is influenced by the values of involvement, but also by co-creation. To test hypothesis 1 and 2, which establishes an effect of involvement on consumer company identification in the form of an inverted U, we will give a value to co-creation equal to the average. Since the variables are centered on the average, this value is 0. as shows in Figure 2.

Therefore, for the case of car industry, hypothesis 1 is fulfilled where it is established that the involvement and consumer company identification have an inverted U form. Following the same methodology outlined in the previous graph, the analysis of the effect of the involvement is carried out, but just for the Fashion industry. For this case, following Figure 2, hypothesis 2 is checked. as shows in Figure 3

In general, it is concluded that regardless of the industry the involvement tends to be negative after a certain level due to conditions associated with the relationship that the consumer can establish with the company and that affects its level of involvement and consumer company identification.

In the case of the quadratic effect between value co-creation and consumer company identification, it can be concluded that in both industries it is possible to demonstrate this behavior. According to above, it can affect the investment of resources of the organization for the development of this strategy in the figures 3 and 4 show the effect of this relationship in the form of an inverted U for the case of the Car industry (hypothesis 3) and for the Fashion industry (hypothesis 4) respectively. as shows in Figure 4.

However, in Figure 3 and 4 the slope of the curve is more pronounced in the case of the Car industry showing a loss of consumer company identification stronger in this industry compared to the Fashion industry. This dynamic can generate that the investment in the co-creation strategy can be perceived more quickly as negative in the Car industry. as shows in Figure 5.

Conclusion

A model is made to establish the quadratic effects of the involvement and the co-creation on consumer company identification. In this research it has been possible to support the relationships between involvement and value co-creation. Similarly, the main objective of the present research was to investigate the gap found in the literature that would allow an empirical analysis of quadratic behaviors of variables such as involvement and consumer company identification. Additionally, there are few studies in the literature in the field of co-creation that speak of the negative aspects of value co-creation that allow us to understand the effects of its implementation as a business strategy.

There are no previous studies that could prove the quadratic effect between involvement and value co-creation. The above because there is a high emphasis on checking their robustness, but at the level linearly unaware of the saturation tendency of these human behaviors (Seelig and Rosof, 2001, Algesheimer, Dholakia & Herrmann, 2005). Additionally, there are few research that have been concerned with knowing the dynamics of consumers in developing countries.

In this sense, this model allows us to cover different gaps in the literature by allowing these relationships to be established in the context of a developing country like Colombia. The results of the model allow to verify a strong relationship between the involvement and the co-creation with the consumer company identification. For the case of the involvement has been discussed especially in the literature related to Psychology, because it has analyzed the parameters of this human behavior. However, the relevance of analyzing involvement and co-creation for the context of marketing is established, especially the field related to consumer behavior (Lindberg et al., 2017; Seelig & Rosof, 2001; Algesheimer, 2005).

The proposed model is consistent with the literature where individual characteristics, such as those concerning the dynamics of social groups, have a direct influence on the processes of social identification (Ashforth & Mael, 1989). In this sense, the results indicate that the involvement has a saturation effect for the Fashion and Car industry. This behavior has a high personal retribution for the consumer because it develops commitment to the products acquired. However, there comes a time when the consumer can show long-term dissatisfaction behavior. It is mean that there is a saturation in to participate in activities with the company due to the loss of interest. Additionally, the association with that consumer has committed too many resources for a product, could produce similar saturation (Lindberg et al., 2017).

The involvement with the company is directly associated to the number of resources invested in the acquisition of a product and that makes it a consumer identified with the company (Lindberg et al., 2017). However, there is a limit to achieve consumer involvement with respect to the volume of resources invested. The above because after a limit investing more resources generate higher levels of demand with respect to the product (Roser, 1990; Lindberg et al., 2017).

Academic Contributions

A very important contribution of the present research is concerned with the presentation of evidence of the quadratic effects that corporate strategies can have. Additionally, the so-called dark side of value cocreation is shown, a phenomenon of great interest for researchers in consumer behavior, but also for researchers in the field of corporate strategy, because it sheds light on the way they behave in implementation by the company. Similarly, it is important to highlight that an important space opens up to identify not only inflection points with company variables but also a space for recover strategies to face this type of service failure.

Managerial Implications

The results suggest important implications for managers and practitioners in the fashion and car sectors. Among these are to consider the life cycles of corporate strategies since they usually present turning points after a time of their implementation. In this regard, the strategy is likely to require new input to revitalize the strategy with its consumers. Another important point to highlight is that consumer company identification, as well as consumer involvement as a means of including the consumer within the company's processes, also requires modifications in its execution that allow re-potentializing efforts in its implementation. An important point is to consider that co-destruction emerges when value co-creation fails to include the consumer. The foregoing introduces a very considered frontier in the joint value creation review and execution processes.

Finally, managers should evaluate more carefully the implementation of this type of strategy that not only contributes to innovation but also to the consumer's involvement with the company. While it is true the expected results are satisfactory, supported for the most part by the literature. It is important that an effort be made to reach consumers who have characteristics that allow generating greater value for the company.

Future Research Lines

An important element to study in the field of value co-creation is the study of the variables of the context in which companies operate and their possible influence on their dynamics. According to the above, it is important to study institutional factors and cultural behavior to identify how they can influence skills and behavior in the provision of a service. On the other hand, it is necessary to study how the strategies adopted by companies may differ in their application considering the different types of consumers. This can contribute directly to understanding not only the dynamics of this type of strategy but also contribute to the study of co-destruction (Chan et al., 2010).

An important point to highlight is that with the arrival of devices with artificial intelligence, the dynamics of interaction between consumers and the provision of a service change. In this way, it is important to identify the possibility of loss of resources in the implementation of this type of new technologies. In the same way, it is necessary to inquire into the possible recovery strategies that can be adopted by companies.

Additionally, a future research line is related with the analysis of quadratic effects with other individual and social variables. The above, with the objective to complement the results achieved in the present research. Similarly, there is a need for longitudinal studies to evaluate behaviors over time and their variation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aiken, L.S., & West, S.G. (1990). Invalidity of true experiments: Self-report pretest biases. Evaluation Review, 14, 374-390.

- Ajzen, I., Rosenthal, L.H., & Brown, T. (2000). Effects of perceived fairness on willingness to pay. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 2439 - 2450.

- Algesheimer, E., Dholakia, U.M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of Marketing, 69(3). 19-34.

- Alonso-Dos-Santos, M., Veinhardt, J., & Calabuig-Moreno, F. (2016) Involvement and image transfer in sports sponsorship. Engineering Economy-Engineering Economy, 27(1), 87 - 7 .

- Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A review & recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411-423.

- Arnould, E.J., Price L.L., & Malshe, A. (2006). Toward a Cultural Resource-Based Theory of the Customer.

- Lusch, R.F., & Vargo S.L. (Ed) In the service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate & directions, Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe, 320-333.

- Ashforth, B.E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory & the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1). 20-39.

- Baron, S., & Harris, K. (2008). Consumers as resource integrators. Journal of marketing management, 24(1/2), 113-130.

- Bartl, M., Füller, J., Mühlbacher, H., & Holger, E. (2006). A manager’s perspective on virtual customer integration for new product development. Journal of Production Innovation Management. Product Development & Management Association.

- Benitez, G.B., Ayala, N.F., & Frank, A.G. (2020). Industry 4.0 innovation ecosystems: An evolutionary perspective on value cocreation. International Journal of Production Economics, 228(107735).

- Blazquéz, M. (2014). Fashion shopping in multichannel retail: The role of technology in enhancing the customer experience. Journal International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 18(4).

- Blodgett, J.G., & Granbois, D.H. (1992). Toward an integrated conceptual model of consumer complaining behavior. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction & Complaining Behavior, 5, 93-103.

- Bourne, C. (2020). Fintech's transparency-publicity nexus: Value cocreation through transparency discourses in business-to-business digital marketing. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(11) Especial Issue 1607-1626.

- Braunsberger, K., & Buckler, B (2011). What motivates consumers to participate in boycotts: Lessons from the ongoing Canadian seafood boycott'. Journal of Business Research, 64, 96-102.

- Caprara G.V., Steca, P., Zelli, A., & Capanna, C (2000). European a new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. Journal of Psychological Assessment.

- Carbonell, P., Rodriguez‐Escudero, A.I., & Pujari, D. (2009). Customer involvement in new service development: An examination of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 26(5), 536- 550.

- Chen, J.-S., Tsou, H.T., & Huang, A.Y.-H. (2009). Service delivery innovation: Antecedents and impact on firm performance. Journal of Service Research, 12(1), 36-55.

- Chowdhury, I.N., Gruber, T., & Zolkiewski, J. (2016). Every cloud has a silver lining — Exploring the dark side of value co-creation in B2B service networks. Industrial Marketing Management. 55, 97-109.

- Cova, B., & Salle, R. (2008). Marketing solutions in accordance with the SD logic: Cocreating value with customer network actors. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(3), 270-277.

- Dahan, E., & Hauser, J. (2002). The virtual customer. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 19, 332-353.

- Daniela C., Ana Isabel Canhoto & Emanuel Said (2020) The dark side of AI-powered service interactions: exploring the process of co-destruction from the customer perspective, The Service Industries Journal.

- Dawson, J.F., & Richter, A.W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 917-926.

- Day, R.L., Grabicke, K., Schaetzle, T., & Staubach, F (1981). The hidden agenda of consumer complaining. Journal of Retailing, 57, 86-106.

- Dong, B., Evans, K.R., & Zou, S (2008). The effects of customer participation in co-created service recovery. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1). 123-137.

- Dong, B., Evans, K., & Zou, S. (2008). The effects of customer participation in co-created service recovery. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 123-137.

- Echeverri, P & Skålén, P. (2011). Co-creation and co-destruction: A practice-theory based study of interactive value formation. Marketing Theory, 11(3). 351-373.

- Echeverri, P., & Skalén, P. (2011). Co-creation and co-destruction: A practice-theory based study of interactive value formation. Marketing Theory, 11(3), 351-373.

- Edvardsson, B. Tronvoll, B. & Gruber, T (2011). Expanding understanding of service exchange and value co-creation: a social construction approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(2). 327-339.

- Edvardsson, B., Enquist, B., & Johnston, R. (2005). Co-creating customer value through hyperreality in the prepurchase service experience. Journal of Service Research, 8(2). 149–161.

- Edvardsson, B., Tronvoll, B., & Gruber, T. (2011). Expanding understanding of service exchange and value co-creation: a social construction approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1-13.

- Ertimur, B., & Venkatesh, A. (2010). Opportunism in co-production: Implications for value co-creation. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18(4), 256-263.

- Fehr, E. & Urs F.(2003). The Nature of Human Altruism. Nature, 425 (6960): 785–91.

- Fenalco (2018). Informe del sector automotor en Colombia.

- Fisk, R.S., Grove, L.C., Harris, D.A., Keeffe, K.L. Daunt (née Reynolds) & Wirtz, J. (2010). Customers behaving badly: A state of the art review, research agenda & implications for practitioners’ Journal of Services Marketing, 24(6), 417-429.

- Franke, N., & Schreier, M. (2010) The “I designed it myself” effect in mass customization. Management Science, 56(1), 125–140.

- Freestone, O., & Mitchell, V.W. (2004). Generation Y attitudes towards e-ethics and internet-related misbehaviours. Journal of Business Ethics, 54, 121–128.

- Füller, J., & Matzler, K. (2007). Virtual product experience and customer participation—A chance for customer-centred. really new products. Technovation, (27), 378-387.

- Füller, J., Bartl, M., Ernst, H., & Mühlbacher, H. (2006). Community based innovation: How to integrate members of virtual communities into new product development. Electronic Commerce Research, 6(2), 57–73.

- Füller, J., Mühlbacher, H., Matzler, K., & Jawecki, G. (2010). Consumer empowerment through internet-based co-creation. Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(3). 71–102.

- Gebauer, J., Fuller, J., & Pezzei, R. (2013). The dark and thebright side of co-creation: Triggers of member behavior in online innovation communities. Journal of Business Research, 66, 1516–1527.

- Gentile, C., Spiller, N., & Noci, G. (2007). How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European. Management Journal, 25(5), 395-410.

- Grönroos, C. (2011). Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Marketing Theory, 11(3), 279-301.

- Grönroos, C., & Voima, P. (2013). Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133-150.

- Gustafsson, A., Kristensson, P., & Witell, L. (2012). Customer co-creation in service innovation: A matter of communication. Journal of Service Management, 23(3), 311–27.

- Hamzelu, B., Gohary, A., Nia, S.G. & Heidarzadeh K.H., (2017). Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics. 29(2), 283-304.

- Heidenreich, S., Wittkowski, K., Handrich, M., & Falk, T. (2014). The dark side of customer co-creation: exploring the consequences of failed co-created services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 1-18.

- Heidenreich, S., Wittkowski, K., Handrich, M. & Falk, T. (2014). The dark side of customer co-creation: Exploring the consequences of failed co-created services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(4), 279-296.

- Hilton, T. (2008). Leveraging Operant resources of consumers: improving consumer experience or productivity? Marketing Review, 8(4), 359-366.

- Homburg, C. & Kühnl, C. (2014) Is more always better? A comparative study of internal and external integration practices in new product and new service development. Journal of Business Research, 67(7), 1360-1367.

- Hoyer, W.D., Chandy, R., Dorotic, M., Krafft, M., & Singh, S.S (2010). Consumer cocreation in new product development. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 283 - 296.

- Inexmoda, (2018). Observatorio de Inexmoda. www.observatorioeconomico.inexmoda.org.co.

- Järvi, H., Kähkönen, A.K., & Torvinen, H. (2018). When value co-creation fails: Reasons that lead to value co-destruction. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 34(1), 63–77.

- Kaplan, A., & Haenlein, M. (2018). Siri, Siri, in my hand: Who’s the fairest in the land? On the interpretations, illustrations, and implications of artificial intelligence. Business Horizons, 62(1), 15–25. https://bdbib.javerianacali.edu.co:2421/10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.004

- Keashly, L., & Neuman, J.H (2008). Workplace behavior project survey.

- Kim, S., Haley, E., & Koo, G.Y. (2009). Comparison of the paths from consumer involvement types to ad responses between corporate advertising and product advertising. Journal of advertising, 38 (3) 67-80.

- Klein., Jill, G, Craig, S.N., & & John, R. (2004). Why we boycott: Consumer motivation for boycott participation. Journal of Marketing, 68(July), 92-109.

- Kristensson, P., Matthing, J., & Johansson, N. (2008). Key strategies for the successful involvement of customers in the co-creation of new technology-based services. International Journal of Service Industry Management. 19(4), 474-491.

- Kwon, S., Ha, S. & Kowal, C. (2017). How online self-customization creates identification: Antecedents and consequences of consumer-customized product identification and the role of product involvement. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 1-13, ISSN 0747-5632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.051.

- Li, C., & Bernoff, J. (2008). Groundswell: Winning in a world transformed by social technologies. Boston, Harvard Business School Press.

- Lindberg, F., & Mossberg, L. (2018). Competing orders of worth in extraordinary consumption community, Consumption Markets & Culture, 22(2), 109-130.

- Lindgreen, A., Hingley, M.K., Grant, D.B., & Morgan, R.E. (2012). Value in business and industrial marketing: Past, present, and future. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(1), 207-214.

- Mahr, D., Lievens, A. & Blazevic, V. (2014). The value of customer cocreated knowledge during the innovation process. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(3).

- Maklan, S.K.S., & Ryals, L. (2008). New trends in innovation and customer relationship management – A challenge for market researchers. International Journal of Market Research, 50(2), 221-240

- Marín, L., Ruiz de Maya, S (2007). The identification of the consumer with the company: Beyond relationship marketing, Universia Business Review.

- O´connor, M., Dollinger, S., Kennedy, S., & Pelletier-Smetko. (1979). Prosocial behavior and psychopathology in emotionally disturbed boys. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 49(2), 301 – 310.

- O’Hern, M S., & Rindfleisch, A. (2009). Customer co-creation: A typology and research agenda. Review of Marketing Research, 6, 84-106.

- O'Connor, M., Dollinger, S., Kennedy, S., & Pelletier-Smetko, P. (1979). Prosocial behavior and psychopathology in emotionally disturbed boys. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 49(2), 301-310.

- Ordanini, A., & Parasuraman, A. (2011). Service innovation viewed through a service dominant logic lens: A conceptual framework and empirical analysis. Journal of Service Research, 14(1), 3-23.

- Payne, A., Storbacka, K., & Frow, P. (2008). Managing the co-creation of value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 83-96.

- Ping, R. A (1996). Interaction and quadratic effect estimation: A two-step technique using structural equation analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 166-175.

- Plé, L., & Cáceres, R.C. (2010). Not always co-creation: Introducing interactional co-destruction of value in service-dominant logic. Journal of Services Marketing, 24(6), 430-437.

- Ramaswamy, V. (2011) It’s about human experiences… & beyond, to co-creation. Industrial Marketing Management, 40, 195-196.

- Ramaswamy, V. (2011) It’s about human experiences… & beyond, to co-creation. Industrial Marketing Management, 40, 195-196.

- Ramaswamy, V., & Gouillart, F. (2010). Building the co-creative enterprise. Harvard Business Review, 8(10), 100-109.

- Rezaei Aghdam, A., Watson, J., Cliff, C., & Miah, S.J. (2020). Improving the theoretical understanding toward patient-driven health care innovation through online value cocreation: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(4), e16324.

- Robertson, N., Polonsky, M., & McQuilken, L. (2014). Are my symptoms serious Dr Google? A resource-based typology of value co-destruction in online self-diagnosis. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 22(3), 246–256. https://bdbib.javerianacali.edu.co:2421/10.1016/j.ausmj.2014.08.009.

- Romero, D., & Molina, A. (2011). Collaborative Networked Organisations & Customer Communities: Value Co-Creation & Co-Innovation in the Networking Era. Production Planning & Control. 22, 447-472. 10.1080/09537287.2010.536619.

- Roser, C. (1990). Involvement, attention, & perceptions of message relevance in the response to persuasive appeals. Communication Research, 17, 571-600.

- Rui, J., & Kai, C. (2021) Impact of value cocreation on customer satisfaction and loyalty of online car-hailing services. Journal of theoretical and applied electronic commerce research, 16(3).

- Rushton, J.I, Chrisjohn, R.D., & Fekken, G.C (1981). The altruistic personality & the self-report altruism scale. Personality & Individual Differences, 2, 292-302.

- Sawhney, M., Verona., & Prandelli, E. (2005). “Collaborating to create: The internet as a platform for customer engagement in product innovation,” Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(4), 4–17.

- Schaarschmidt, M., Walsh, G., & Evanschitzky, H. (2018). Customer interaction and innovation in hybrid offerings: Investigating moderation and mediation effects for goods and services innovation. Journal of Service Research, 21(1), 119-134.

- Seelig, B.J., & Rosof, L. (2001). Normal & pathological altruism. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 49(3), 933 – 959

- Seth, A., Song, K.P., & Pettit, R. (2000). Synergy, managerialism or hubris? An empirical examination of motives for foreign acquisitions of US firms, Journal of International Business Studies, 31, 387-405.

- Sjódin, C., Kristensson, P. (2012). Customers experiences of co-creation during service innovation. International. Journal of Quality & Service Sciences, 4(2), 189-204.

- Smith, A.M. (2013). The value co-destruction process: A customer resource perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 47(11/12), 1889–1909. https://bdbib.javerianacali.edu.co:2421/10.1108/EJM-08-2011-0420

- Stokburger-Sauer, N. E., Scholl-Grissemann, U., Teichmann, K., Wetzels, M. (2016). Value cocreation at its peak: The asymmetric relationship between coproduction and loyalty. Journal of Service Management, 27(4), 563-590. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-10-2015-0305.

- Tram-Anh, N.P., Sweeney, J.C., Soutar, G.N. (2020). Customer effort in mandatory and voluntary value cocreation: A study in a health care context. Journal Of Services Marketing.

- Vargo, S.L. (2008). Customer integration and value creation: Paradigmatic traps and perspectives. Journal of Service Research, 11(2), 211-215.

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1-17.

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of marketing Science, 36(1), 1-10.

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F. (2011). It's all B2B…and beyond: Toward a systems perspective of the market Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 181-187.

- Vargo, S.L., & Lusch, R.F (2006). Service-dominant logic: What it is, what it is not, what it might be.

- In, Lusch, R.F., & Vargo, S.L. (Edsition). The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, & directions 43–56. Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

- Vargo, S.L., Lusch, R.F., & Akaka, M.A. (2010). Advancing service science with service-dominant logic: Clarifications and Conceptual Development. In P. P. Maglio, C. A. Kieliszewski & J. C. Spohrer (Eds.), Handbook of service science, 133-156.

- Vargo, S.L., Maglio, P.P., & Akaka, M.A. (2008). On value and value co-creation: A service systems and service logic perspective. European Management Journal, 26(3), 145-152.

- Vaughn, R. (1980). How advertising works: A planning model. Journal of Advertising Research, 20, 27-30.

- Vaughn, R. (1986). How advertising works: a planning model revisited. Journal of Advertising Research, 26, 57-65.

- Von Hippel, E., Katz, R. (2002). Shifting innovation to users via toolkits. Management Sci, 48(7),821–833.

- Wirtz, J., & McColl-Kennedy, J.R. (2010). Opportunistic customer claiming during service recovery. Journal of Retailing, 38, 654-675.

- Wirtz, J., & Kum, D. (2004). Consumer cheating on service guarantees. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(2), 159-175.

- Ye, Hua (Jonathan), Kankanhalli, A. (2020) Value cocreation for service innovation: Examining the relationships between Service Innovativeness, customer participation, and mobile app performance. Journal Of The Association For Information Systems, 21(2), 292-311.

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 341-352.

- Zhang, T., Lu, C., Torres, E., & Chen, P.J. (2018). Engaging customers in value co-creation or co-destruction online. Journal of Services Marketing, 32(1), 57–69.