Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

Determinants of Purchase Intention towards Social Enterprise Personal Care Brands: A Pls-Sem Approach

Christian James B. Lopez, De La Salle University

Alyanna Marie C. Santana, De La Salle University

Lorraine Nicole S. Tan, De La Salle University

Shaniel Ginn R. Villaflor, De La Salle University

Rayan P. Dui, De La Salle University

Miguel Paolo L. Paredes, De La Salle University

Abstract

This research is interested in understanding, based on a modified conceptual model derived from the theory of planned behavior, what drives purchase intention of personal care products from social enterprises based on the perspective of working millennials. This study employed a correlational research design based on an electronic survey answered by 115 respondents. Partial least squares structural equation modelling was used as the statistical tool to analyze patterns and relationships between latent variables. Brand credibility, communalbrand connection, and self-efficacy are positively related to purchase intention. Previous purchase indirectly influenced intention through the three antecedents. This research is limited to cross-sectional data of working millennials in the philippines and focused the scope on understanding purchase intention. This paper is novel because of the constructs used to operationalize the generic antecedents of theory of planned behavior. Instead of general questions on attitude, norms, and perceived control, the authors adopted marketing-specific constructs that provide more insight for social enterprise marketers and scholars.

Keywords

Purchase Intention, Theory of Planned Behavior, Social Enterprises, Personal Care, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling.

Introduction

A generation born in a digitally connected world whose characteristics and traits are distinct from those that came before them, Generation Y or millennials are set to dominate the labor force for the years to come with their increasing purchasing power influencing the global market to target their generation above all else. In what was previously thought to be a saturated market, the Personal Care industry continues in its relentless pursuit for customers who want to take care of themselves and their skin. But there are new players in the Philippine market who albeit seek to do the same, are also driven to find ways in taking care of the planet and the people who live in it-these are called social enterprises. With these developments, the question this research sought to answer was: what drives the intent of Filipino millennials to purchase personal care products from social enterprises?

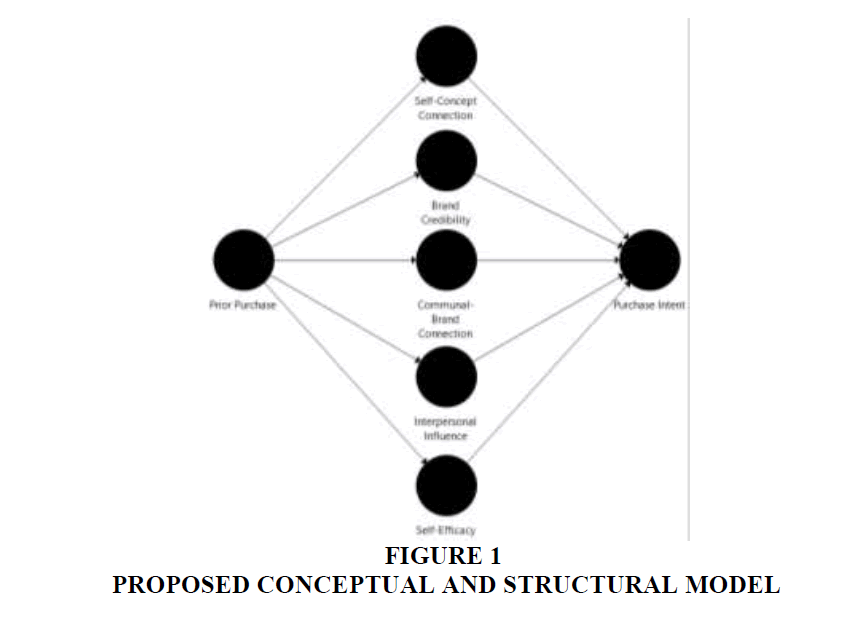

In this context, this research focuses on determining factors that affect the purchase intentions of working Filipino millennials anchored on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by Ajzen (1991). Instead of adopting the general antecedents of intention, the researchers sought to specify the constructs into marketing and brand-related determinants. These determinants are: (1) self-concept connection and (2) brand credibility as proxies for attitude towards behavior; (3) communal-brand connection and (4) interpersonal influence as proxies for subjective norms; and purchase self-efficacy as a proxy for perceived behavioral control. This research administered an online survey through purposive sampling, gathering data from 115 individuals. The results were analyzed through partial least squares structural modelling.

Literature Review And Hypotheses

Filipinos, more than ever, are increasingly becoming health-conscious and are paying more attention to their physical appearances. The rise of purchasing power and improving standards of living have paved the way for new players to enter the market, including a new type of business entity called a social enterprise, like its mainstream counterparts, strives to gain profits, but in doing so, also accomplishes social and environmental objectives (British Council Philippines, 2015). A majority of their customers are those born between the year 1981 - 1999, who form Generation Y or are more commonly known as Millennials (Bolton et al., 2013).

Purchase Intention

Purchase intention is defined by Fandos & Flavian (2006) as an implied commitment to one’s self to avail or purchase when the ability to do so arises. This construct is given high importance of consideration by businesses as it holds the ability to forecast sales (Goyal, 2014) and is positively correlated with buying behavior (Morwitz & Schmittlein, 1992). The discernment of purchase intentions amongst target markets make up a critical element for enterprises to survive in competitive environments. While causal mechanisms of purchase intentions have largely been addressed in numerous researches, it is of significant importance for enterprises to continually seek new insights on segments which are in constant evolution in line with social, political, technological, and demographic contexts of which they participate in.

Attitude Towards Behavior

Attitude towards behavior is defined as an individual’s likelihood to perform a specific behavior due to positive perceptions (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977). Individuals are said to formulate unique responses that reflect their perceived attitudes. In relation to marketing, a study by Rao (2010) defined it as an individual’s comprehensive assessment of a certain product or service. Several studies claim and support that this determinant is likely to be the strongest predictor in the TPB as increasing perception of likelihood can be relatively accomplished through interventions of assessments and improvements.

Self-concept Connection is defined as ‘a totality of the individual’s thoughts and feelings having reference to himself as an object (Sirgy, 1982). This concept was extended by Coman & Sas (2016) as an individual’s attachment of self-image towards a certain possession which can be both physically and metaphorically to serve as a function of self-enhancement. The need to understand interactions and relationships between self-concept and consumer behavior has brought forth various theoretical hypotheses for its address. Amongst these, the self-image congruity hypotheses, first generated by studies by Trucker (1957), state that products have personalities of their own, based on brand perceptions, or associations formed from them. These associations may stem from physical features of the product, exhibition, packaging, advertising, or price (Sirgy, 1982). These perceptions then, serve as basis for consumer behavior as it is stated that consumers often gravitate towards products which are congruent to their own selfconcepts, whether these are actual or idealized. Thakur & Kaur (2015) state that self-concept connection has a significantly positive effect towards consumer-brand relationships, it carries a higher significance for the brand as it helps them market and communicate their brand. This construct is also a powerful tool in generating consumer image on both a group and individual level towards an intention for purchase (Swaminanthan et al., 2007).

H1-1: Self-concept connection is positively related with purchase intention of personal care social enterprise products.

Brand credibility is composed of two main concepts which are brand and credibility. A classic definition provided by Kotler (1997) defines brand as a name, term, sign, or symbol that represents the unique value proposition and culture of a certain company, product, or service. As a combined concept, brand credibility is stipulated as an accumulation of the public’s perceptions with regard to an organization’s past marketing initiatives (Erdem et al., 2002). In relation to this study, Wang & Yang (2010) revealed that brand credibility is directly linked with positive influence on a consumers’ purchase intention. Two external factors namely, brand image and brand awareness were also identified to positively control the relationship between brand credibility and a consumers’ purchase intention.

H1-2: Brand credibility is positively related with purchase intention of personal care social enterprise products.

Subjective Norm

Subjective norm is an individual’s perception of social pressure from the people around him in whether doing a specific behavior or not (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977). In simpler terms, it is the recognizable opinion of others who are close and important to the individual (Kim et al., 2013). A study by Al-Matari (2014) found that Subjective Norms have a direct significant impact on buying intentions. Individuals who reported a more positive attitude toward purchasing a product and who perceived support for consumption from those around them reported significantly stronger intentions (Smith et al., 2008). In some studies, they often criticize the weak or non-existent relationship between subjective norm and the intention in the TPB (Ham et al., 2015).

Communal-brand connection is when consumers seek a meaningful communal identification and connection with fellow brand users, while providing them a sense of order and security, thus forming a brand community (Rindfeisch et al., 2009). To expound on brand community, Muniz & O’Guinn (2001) defined it as a specialized, non-geographically bound community, based on a structured set of social relationships among admirers of a brand. Communal-brand connection promotes what Bender coined as “we-ness”. As cited by Muniz and O’Guinn, it is wherein the members of the community feel an important connection to the brand, but more importantly, they feel a stronger connection toward one another. They feel that they know each other at some level, even if they have never met. In relation to subjective norm, brand communities give consumers a sense of belongingness within the brand community, thus also having a positive influence on their purchase intention (Liaw & Jen, 2008). A study by Hedlund (2011) also found that consumers purchase products bought by other members in the community in order to feel as they fit in the community.

H2-1: Communal-brand connection is positively related with purchase intention of personal care social enterprise products. Interpersonal influence is a type of social influence that results from other group members encouraging conformity and discouraging nonconformity. Susceptibility on Interpersonal Influence, which is defined by Bearden (1989), is the need to identify or enhance one’s image with significant others through the purchasing and use of products and brands, the willingness to conform to the expectations of others regarding purchase decisions, and/or the tendency to learn about products and services by observing and seeking information from others.

H2-2: Interpersonal influence is positively related with purchase intention of personal care social enterprise products.

Perceived Behavioral Control

Yzer (2012) stated that perceived behavioral control answers the person’s question “Can I do it?” and then he or she considers performing a particular behavior. Perceived behavioral control reflects beliefs regarding the access to resources and opportunities needed to perform a behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Taylor & Todd, 1995). With regard to purchase intention, Chung and Kim (2011) stated that there is a strong correlation between the strength of perceived behavioral control and the strength of the positive relationship between attitude and purchase intention.

Self-efficacy is defined as “people’s beliefs about their capabilities to produce performances that influence events affecting their lives” (Bandura, 1995). Specifically, purchase self-efficacy pertains to one’s perception of possessing capabilities and resources to purchase a product. Data from Li et al. (2018) showed that purchase self-efficacy had a significant effect on purchase intention. This implies that when consumers have a perception of greater control that they can enhance their self-efficacy, they also induce stronger purchase intention. With regards to purchase intention, Armitage & Conner (2001) expressed that accumulated evidence suggests that self-efficacy is not only an important addition to the theory, but it frequently emerges as the most significant predictor of both intention and behavior.

H3: Purchase self-efficacy is positively related with purchase intention of personal care social enterprise products.

Prior Purchase

Fishbein & Ajzen (2011) posit that certain background factors, such as personality and prior experiences, shape one’s attitude, norms, and perceptions of control towards intention and behavior. Past purchasing has been seen to predict intentions to purchase (Weisberg et al., 2011). Prior experience in purchase is argued as significant as the experience reduces anxiety in future purchases (Weisberg et al., 2011), as individuals with prior positive knowledge may lead to increase trust that their positive experience will be replicated in future purchases. Specific to this paper’s study, one’s prior purchase of a personal care product of a social enterprise can help shape perceptions on the brand.

H4: Self-concept connection, brand credibility, communal-brand connection, interpersonal influence, and purchase self-efficacy mediates the relationship between prior purchase and purchase intention.

Theoretical And Conceptual Framework

The paper utilized the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) as the foundation of the study. TPB was first introduced by Icek Ajzen (1991) and rests on the theory that three variables are the best predictors of intention: (1) attitudes toward behavior or how people behave rationally when deciding to act, (2) subjective norm or how people act by conscious or unconscious motives, and (3) perceived behavioral control or people’s consideration of their actions before the act. The dependent variable, intention, refers to motivational factors that influence a person to perform a specific behavior (Miles, 2012; Ajzen, 1991). In the TPB, prior experiences are considered as background factors that serve as antecedents to attitudes, norms, and perceived control.

As shown in Figure 1, this research adapted the five determinants (i.e., Self-Concept Connection, Brand Credibility, Communal-Brand Connection, Interpersonal Influence, and Self- Efficacy) in understanding purchase intention. For ease of presentation, the indicators of the measurement model, which were all treated as reflective, are not shown in the figure. More information about the operationalization of the conceptual framework will be discussed in the methods section.

Methodology

This research facilitated a survey questionnaire that incorporates different scales supported by literature. The paper used the Likert Scale, ranging from 1 (negative) to 7 (positive). Presence of prior purchase was coded in binary manner: 1 for Yes and 0 for No. Items pertaining to the constructs were all adopted from literature. Given the complexity of exogenous and endogenous variables and unexplored nature of the conceptual framework, it is important to employ an appropriate statistical procedure. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is suitable for examining theory development as proposed by Hair et al. (2017) and Lowry & Gaskin (2014). PLS-SEM is best when the data violates normality of distribution and when the model contains mediation (Hair et al., 2014; Hair et al., 2017). Moreover, PLS-SEM is a nonparametric procedure preferable to covariance-based structural equation modeling and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression in cases of no normality and small sample sizes (Hair et al., 2011). The sample size calculations were derived from Hair et al. (2014, p. 21) based on the structural model. Since the maximum number of arrows directed at a construct (purchase intention) equals to 5, adopting the significance level of 0.05, expecting a minimum statistical power of 80%, and minimum r-squared of 0.25, the recommended minimum sample size is 70. The data gathered was 115 respondents, which beyond the recommended minimum. To conduct PLS-SEM, the SmartPLS 3 (Ringle et al., 2015) software was used. All latent variables were considered to have reflective indicators. Factor analyses, tests of construct validity and reliability, tests for discriminant validity, tests for multicollinearity, and model fit were all performed in SmartPLS 3 as well, guided by Hair et al. (2017); Lowry & Gaskin (2014). The usual PLS algorithm method and bootstrapping (J = 10,000) were employed as suggested by Ringle et al. (2015). As recommended by Kock (2014), this study utilized one-tailed p-value tests of significance since the a priori hypotheses inferred on the direction and signs of the variables relationships, which are backed by prior research.

Data Analysis

Data was gathered from 115 respondents from an online survey administered through Google Forms. The respondents had to fit the criteria which was being a Millennial born between 1981 - 1999 and is currently working within the Taguig area. Most responses were obtained from those born in 1997 and 1998 and majority of respondents are female.

Before conducting analysis of the structural model, it is important to establish the reliability and validity of the measurement model. Table 1 summarizes the model tests of construct reliability and validity, discriminant validity, non-multicollinearity, absence of common method bias, and goodness-of-fit. To examine construct reliability and validity, each indicator and their respective latent variables were considered in computing for Cronbach’s alpha (must be greater than 0.70), composite reliability (must be greater than 0.70), and average variance extracted (AVE must be greater than 0.50). In addition, to assess discriminant validity, cross-loadings of the questions were examined through factor analysis conducted in SmartPLS. All reliability scores and factor loadings for the latent variables were deemed acceptable, following the recommendations of Lowry and Gaskin (2014) and Hair et al. (2017). Furthermore, there were no significant cross-loadings, and the model passed the Fornell-Larcker and Heterotrait-Monotrait criteria (HTMT) signifying discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2017; Lowry & Gaskin, 2014; Ringle, Wende, & Becker, 2015). To test for multicollinearity, it is essential to look at variance inflation factors of the indicators (VIF). All VIFs were less than 10.00, hence there was no significant multicollinearity among the indicators.

| Table 1: Model Tests Of Reliability, Validity, Multicollinearity, And Goodness Of Fit Based On Pls Algorithm | ||||||||

| Constructs and Code | Items | Loadings | Variance Inflation Factor | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted | R-squared | Adjusted R-squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Credibility | 1.601 | 0.889 | 0.931 | 0.818 | 0.182 | 0.175 | ||

| ATB_BC1 | Social Enterprises in the Personal Care Industry have brands that can be trusted | 0.906 | 2.688 | |||||

| ATB_BC2 | Social Enterprises that sell personal care products are committed to delivering on their claims, no more and no less. | 0.921 | 3.256 | |||||

| ATB_BC3 | Based on my experience, Social Enterprises that sell personal care products will keep their promises, no more and no less. | 0.886 | 2.29 | |||||

| Communal-Brand Connection | 2.94 | 0.872 | 0.912 | 0.721 | 0.126 | 0.118 | ||

| SN_CBC1 | I identify with people who purchase personal care products from Social Enterprises. | 0.877 | 2.269 | |||||

| SN_CBC2 | I feel that I belong to a group if I purchase personal care products from Social Enterprises. | 0.781 | 1.827 | |||||

| SN_CBC3 | Social Enterprise personal care products are used by people like me. | 0.871 | 2.202 | |||||

| SN_CBC4 | I feel a deep connection with others who use Social Enterprise personal care products. | 0.864 | 2.396 | |||||

| Interpersonal Influence | 1.561 | 0.855 | 0.901 | 0.695 | 0.011 | 0.002 | ||

| SN_II1 | If I want to be like someone, I often try to buy the same brands that he or she buys. | 0.818 | 1.941 | |||||

| SN_II2 | It is essential that people important to me like the products and brands I buy. | 0.816 | 2.129 | |||||

| SN_II3 | I achieve a sense of belonging when I purchase the same products and brands that people important to me also do. | 0.88 | 2.917 | |||||

| SN_II4 | I like to know what brands and products make good impressions on others. | 0.819 | 1.64 | |||||

| Self-Concept Connection | 2.41 | 0.868 | 0.919 | 0.791 | 0.185 | 0.178 | ||

| ATB_SC1 | I have a lot in common with Social Enterprise in the Personal Care Industry. | 0.904 | 2.348 | |||||

| ATB_SC2 | The image of Social Enterprise brands in the Personal Care Industry and my self image are similar in a lot of ways. | 0.894 | 2.529 | |||||

| ATB_SC3 | I feel a deep connection with people who use Social Enterprise brands in the Personal Care Industry. | 0.87 | 2.072 | |||||

| Self-Efficacy | 1.383 | 0.901 | 0.938 | 0.834 | 0.1 | 0.092 | ||

| PBC_SE1 | I believe I have the ability to purchase personal care products from Social Enterprises. | 0.877 | 2.761 | |||||

| PBC_SE2 | I am confident that I will be able to purchase personal care products from Social Enterprises. | 0.949 | 4.09 | |||||

| PBC_SE3 | I am capable of purchasing personal care products from Social Enterprises in the next month. | 0.912 | 2.714 | |||||

| Purchase Intention | - | 0.932 | 0.956 | 0.88 | 0.616 | 0.598 | ||

| PIN1 | The probability of my purchasing a Social Enterprise personal care product is (1 – low, 7 – high) | 0.946 | 4.47 | |||||

| PIN2 | The probability that I would consider Social Enterprise personal care | 0.943 | 4.55 | |||||

| products is (1 – low, 7 – high) | ||||||||

| PIN3 | I am willing to purchase personal care products from Social Enterprises | 0.924 | 3.151 | |||||

Since the tests for reliability, validity, and multicollinearity pertaining to the measurement model were deemed acceptable, the next stage in PLS-SEM is to assess the structural model and its paths can be analyzed appropriately. Table 2 features path estimates and p-values, which was the result of the initial PLS algorithm and bootstrapping procedure (J=1,000) performed through SmartPLS, as recommended by Hair et al. (2017) and Lowry and Gaskin (2014). Table 3 showed the final PLS algorithm and bootstrapping results (J=5,000), which highlighted the most salient relationships in understanding purchase intention of social enterprise personal care product.

| Table 2: Results of the initial pls algorithm and bootstrapping | ||||

| Direct Effects | Path Estimates | STDEV | t-Statistics | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Credibility -> Purchase Intent | 0.271 | 0.083 | 3.236 | 0.001 |

| Communal-Brand Connection -> Purchase Intent | 0.237 | 0.126 | 1.878 | 0.030 |

| Interpersonal Influence -> Purchase Intent | -0.018 | 0.080 | 0.220 | 0.413 |

| Prior Purchase -> Brand Credibility | 0.431 | 0.078 | 5.454 | <.001 |

| Prior Purchase -> Communal-Brand Connection | 0.359 | 0.081 | 4.360 | <.001 |

| Prior Purchase -> Interpersonal Influence | 0.114 | 0.101 | 1.023 | 0.153 |

| Prior Purchase -> Self-Concept Connection | 0.435 | 0.077 | 5.618 | <.001 |

| Prior Purchase -> Self-Efficacy | 0.317 | 0.095 | 3.309 | <.001 |

| Self-Concept Connection -> Purchase Intent | 0.107 | 0.105 | 1.034 | 0.151 |

| Self-Efficacy -> Purchase Intent | 0.395 | 0.074 | 5.275 | <.001 |

The results of the initial run showed that interpersonal influence and self-concept connection were not statistically significant predictors, while the remaining constructs were positively related with purchase intent. Thus, these results fail to support H1-1 and H2-2. These statistically insignificant predictors were removed in the model, then another round of PLS algorithm and bootstrapping procedures were taken. Table 3 details the final results of direct relationships between the latent variables.

| Table 3: Results Of The Final Pls Algorithm And Bootstrapping | ||||

| Direct Effects | Path Estimates | STDEV | t-Statistics | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand Credibility -> Purchase Intent | 0.294 | 0.077 | 3.859 | <.001 |

| Communal-Brand Connection -> Purchase Intent | 0.292 | 0.080 | 3.594 | <.001 |

| Prior Purchase -> Brand Credibility | 0.429 | 0.076 | 5.597 | <.001 |

| Prior Purchase -> Communal-Brand Connection | 0.359 | 0.081 | 4.352 | <.001 |

| Prior Purchase -> Self-Efficacy | 0.315 | 0.092 | 3.424 | <.001 |

| Self-Efficacy -> Purchase Intent | 0.400 | 0.070 | 5.718 | <.001 |

The results of the final run showed that self-efficacy has the highest effect on purchase intention. Brand credibility and communal-brand connection had virtually the same strength in predicting purchase intention based on the sample. These results provided evidence to support H1-2 and H2-1. Furthermore, prior purchase was positively related with brand credibility, communal-brand connection, and self-efficacy. Given these findings, the mediation hypothesis (H4) can now be properly tested through bootstrapping. Table 4 details the specific indirect effects of prior purchase on intention through brand credibility, communal-brand connection, and self-efficacy.

| Table 4: Results Of The Prior Purchase’s Specific Indirect Effects On Purchase Intention | ||||

| Specific Indirect Effects of Prior Purchase to Purchase Intent | Path Estimates | STDEV | T Statistics | P Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Purchase -> | ||||

| Brand Credibility -> Purchase Intent | 0.126 | 0.041 | 3.136 | 0.001 |

| Communal-Brand Connection -> Purchase Intent | 0.106 | 0.041 | 2.483 | 0.007 |

| Self-Efficacy -> Purchase Intent | 0.127 | 0.046 | 2.745 | 0.003 |

The results highlighted that the three paths were valid in predicting purchase intent. Brand credibility, communal-brand connection, and self-efficacy fully mediated the relationship between prior purchase and purchase intention. However, H4 aimed to test the possible mediating effects of the statistically insignificant predictors (interpersonal influence and selfconcept connection), these results only provide partially validated the hypothesis.

Discussion, Conclusions And Recommendations

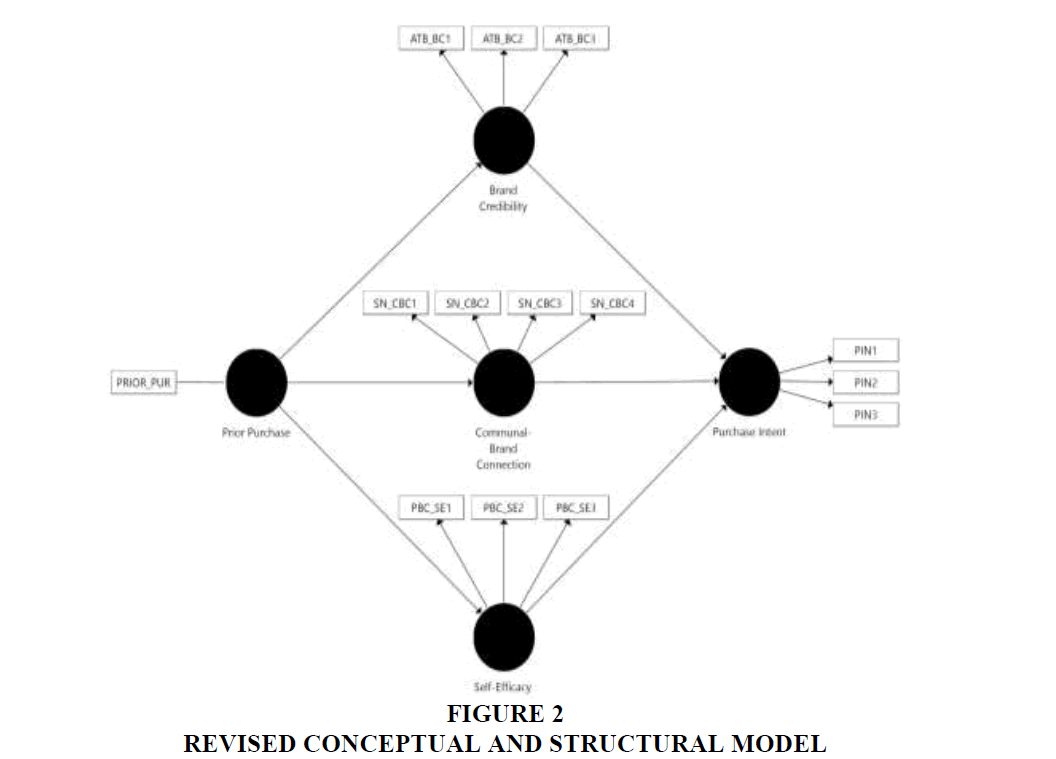

To summarize, the partial least squares structural equation modeling approach was able to validate H1-2, H2-1, H3, and H4. Specifically, brand credibility (a marketing-specific proxy for attitude towards behavior), communal-brand connection (a marketing-specific proxy for subjective norms), and self-efficacy (used to measure perceived behavioral control) were directly and positively related to purchase intention. Prior purchase intention also indirectly affected purchase intent through the three mediators. Figure 2 visualizes the revised structural model of this research based on the results of the PLS-SEM analysis.

Brand credibility is an accumulation of the perceptions with regards to an organization’s past marketing initiatives (Erdem et al., 2002). In marketing, a brand plays a big role in determining purchase intention as it is the front image of a business. According to the answers of respondents in the open-ended questions of the survey pertaining to why they purchase a social enterprise’s personal care product, they cited good reviews and dependability as their top reasons. On the other hand, literature supports that when consumers are unfamiliar with the brand, it causes them to feel at risk and thus, this hinders them from developing intentions to purchase. Therefore, the implication for social enterprise marketers is that it is important to highlight the value propositions of their brands and products and not just focus on communicating their mission. The findings of this study support that credibility emanates from solving customer’s personal care problems and a social enterprise’s authentic pursuit of their advocacy.

Communal-brand connection is the meaningful shared identification and connection with fellow brand users, while providing them a sense of order and security in a brand community (Rindfeisch et al., 2009). Therefore, this supports the notion that if the customers feel that they belong to a group of advocates that support a social enterprise brand, they are likely developing stronger purchase intention. This implies that for social enterprise marketers, it is important to cultivate marketing and branding messages that encourage community-building among customers, since they can reinforce each other to support a social enterprise’s personal care products.

Self-efficacy is the feeling of confidence in one's own ability has been characterized as essential for any behavior to take place, these beliefs in turn reflect a consumer's perceived capability to purchase (Dequech, 2000). Among the antecedents, self-efficacy has the strongest effect on purchase intention. This implies that social enterprise marketers should be able to frame their pricing strategies based on the perceived self-efficacies or perceived ability to pay of customers. This is an essential insight, since social enterprise marketers might be tempted to position social enterprise personal care brands as luxury. Doing so may alienate the working millennial market surveyed in this research, since self-efficacy, in conjunction with brand credibility and communal-brand connection; help cultivate customers’ purchase intention.

The reasoned action approach of Fishbein & Ajzen (2011) argues background factors influence one’s attitude, norms, and perceptions of control towards intention. In the context of this marketing-related study, prior purchase of a social enterprise personal care product contributes to the formation of purchase intention through a heightened sense of brand credibility, communal-brand connection, and self-efficacy. This implies that for social enterprise marketers, campaigns that encourage repeat purchase or loyalty-based programs should be explored. Since prior purchase is fully mediated by the three aforementioned predictors, the campaigns and programs could include elements that cultivate community and brand building among customers.

This research recommends that future studies could explore whether the revised conceptual framework is applicable to other categories beyond personal care, such as food, household care, and the like. Moreover, this study is limited to a sample that is explicitly targeted by both commercial and social enterprises. It is interesting to explore the drivers of purchase intent among non-targets and whether the model would still be empirically validated in this context. Finally, longitudinal research can explore if purchase intention leads to actual behavior, which is beyond the scope of this study.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977).Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 888-918.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Al-Matari, E.M., Al-Swidi, A.K., & Fadzil, F.H.B. (2014). The measurements of firm performances’ dimensions. Asian Journal of Finance and Accounting, 6(1), 24.

- Armitage, C.J., & Conner, M. (2000). Social cognition models and health behavior: A structured review. Psychology and Health, 15, 173-189.

- Bandura, A. (1995). Perceived self-efficacy. Blackwell Encyclopedia of social psychology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 1995: 434-436.

- Bearden, W.O., Netemeyer, R.G., & Teel, J.E. (1989). Measurement of consumer susceptibility to interpersonal influence. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(4), 473.

- Bolton, R.N., Parasuraman, A., Hoefnagels A., Migchels N., Kabadayi S., Gruber T., Loureiro Y.K., & David Solnet. (2013). Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 7(3), 245-267.

- Chung J.E. & Kim H.Y. (2011). Consumer purchase intention for organic personal care products. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 40-47.

- Coman, A., & Sas, C. (2016). Designing personal grief rituals: An analysis of symbolic objects and actions. Death studies, 40(9), 558-569.

- Dequech, D. (2000). Confidence and action: A comment on barbalet. Journal of Socio-Economics, 29(6), 503-516.

- Erdem, T., Louviere, J., & Swait. J. (2002). The impact of brand credibility on consumer price sensitivity. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19(1), 1-19.

- Fandos, C., & Flavián, C. (2006). Intrinsic and extrinsic quality attributes, loyalty and buying intention: An analysis for a PDO product. British Food Journal, 108(8).

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press.

- Goyal, R. (2014). A Study on Purchase Intentions of Consumers towards Selected Luxury Fashion Products with special reference to Pune Region. D. Y. Patil University School of Management.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139-152.

- Ham, M., Jeger, M., & Ivković, A.F. (2015). The role of subjective norms in forming the intention to purchase green food. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 28(1), 738-748.

- Hedlund, D.P. (2011). Sport brand community, PhD dissertation, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL.

- Kim, E., Ham, S., Yang, I.S., & Choi, J.G. (2013). The roles of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control in the formation of consumers’ behavioral intentions to read menu labels in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 203-213.

- Kotler, P. (1997). Marketing management (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Li, Y., Xu, Z., & Xu, F. (2018). Perceived control and purchase intention in online shopping: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Social Behavior and Personality. An International Journal, 46(1), 99-105.

- Liaw, G.F., & Jen, F. (2008). A study on the influence of consumers’ participation in a brand community on their purchase intention. Paper presented at the 8th Global Conference on Business and Economics.

- Lowry, P.B., & Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 57(2), 123-146.

- Miles, J.A. (2012). Management and Organization Theory (1st ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Morwitz, V.G., & Schmittlein, D. (1992). Using segmentation to improve sales forecasts based on purchase intent: Which intenders actually buy? Journal of marketing research, 391-405.

- Pedersen, P.E. (2002). Using the theory of planned behavior to explain teenagers ' adoption of text.

- Rao Gogineni, R., April E.F., & Nyapati R.R. (2010.) International Medical graduates in child and adolescent psychiatry: Adaptation, training, and contributions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 19, 833-853.

- Rindfeisch, A., Burroughs, J. E., & Wong, N. (2009). The safety of objects: Materialism, Existential insecurity, and brand connection. Journal of Consumer Research, 36(1), 1-16..

- Sirgy, M.J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of consumer research, 9(3), 287-300.

- Smith, J.R., Terry, D.J., Manstead, A.S., Louis, W.R., Kotterman, D., & Wolfs, J. (2008). The attitude–behavior relationship in consumer conduct: The role of norms, past behavior, and self-identity. The Journal of Social Psychology, 148(3), 311-334.

- Swaminanthan, V., Winterich, K.P., Zeynep, G.C. (2007). My brand or our brand: The effects of brand relationship dimensions and self- construal on brand evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 248-259.

- Thakur, A., & Kaur, R. (2015). Relationship between self-concept and attitudinal brand loyalty in luxury fashion purchase: A study of selected global brands on the Indian market. Management Journal of contemporary management issues, 20(2), 163-180.

- Wang, X., & Yang, Z. (2010). The effect of brand credibility on consumers’ brand purchase intention in emerging economies: The moderating role of brand awareness and brand image. Journal of Global Marketing, 23(3), 177-188.

- Yzer, M. (2012).Perceived behavioral control in reasoned action theory. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 640(1), 101-117.