Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 2

Effect of the Organisational Culture on Crisis Management in Hotel Industry: A Qualitative Exploration

Maisoon Abo-Murad, AL-Balqa Applied University

Abdullah AL-Khrabsheh, AL-Balqa Applied University

Rossilah Jamil, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia

Abstract

Earlier studies that investigated the effect of organisational culture on crisis management adopted an orthodox view. Furthermore, all studies focused on the post-crisis stage. These limitations prevented an understanding of the crises and disabled the alignment of the organisational culture, organisational learning and crisis management. This study explored the organisational cultural barriers affecting crisis management, primarily in the hotel industry. The researchers interviewed the hoteliers, legislators, and government officials from the Malaysian hotel industry. Secondary data, which included documents from the government, hotel cases and hotel associations, was collected and analysed using the Nvivo 10 software. Results indicated that the organisational culture significantly influenced crisis management throughout the crisis stages. This study noted many organisational and cultural barriers that affected the crisis management. All cultural barriers were interrelated throughout the crisis stages. A fourth cultural barrier was noted and an integrated crisis management model was proposed. The theoretical and practical effects of all parameters were discussed and further suggestions were made.

Keywords

Crisis Management, Hotel Industry, Organisational Culture, Organisational Barriers, Organisational Learning, Turnover Culture.

Introduction

Crises can adversely affect any organisation (Pearson & Clair 1998; Bundy et al., 2017). In a VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous) world, an effective crisis management can improve the organisational performance (Burnett, 1998; Robert & Lajtha, 2002; Wang & Belardo, 2005). Traditional techniques that use a reactive style for managing crises are inadequate. Due to an increased frequency of the crises, the organisations have to adopt a proactive crisis management approach (Smith & Elliott, 2006; Crandall et al., 2013; Alonso- Almeida et al., 2015).

Organisational culture facilitates crisis management (Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Elliott & Smith, 2006; Smith & Elliott, 2007; Veil, 2011; Topper & Lagadec, 2013). The cultural barriers influence the manner in which the crises are resolved, hence, a favourable culture improves the crisis management (Ritchie et al., 2011). The organisations must learn from the crises. Organisational learning ensures the detection and correction of errors (Senge, 2014). The earlier studies did not investigate the role played by organisational learning in crisis management (Lalonde, 2007; Deverell, 2012; Antonacopoulou & Sheaffer, 2014). If the companies implement organisational learning, they can overcome the cultural barriers during crisis management.

Problem Statement

Crisis management increases the organisation’s survival (Robert & Lajtha, 2002), reputation (Jaques, 2014) and performance (Wang & Belardo, 2005). Yet, several organisations are unprepared for crises (Sahin 2008; Bundy et al., 2017) or adopt a reactive crisis management approach (Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015), though a proactive crisis management is important (Hart & Sundelius, 2013; Alexander, 2016).

Organisational culture increases a company’s crises-preparedness (Veil, 2011) and differentiated the crisis-prepared and crisis-prone organisation (Deverell & Olsson, 2010; Topper & Lagadec 2013). However, the effect of organisational culture on crisis management is low and the existing crisis studies are fragmented (James, 2011). Jaques (2010) owes this fragmentation to a linear paradigm that assesses the crises and contradicts their dynamic nature. Earlier studies investigated the organisational culture using an independent scheme of crisis stages like preparing the organisation for future crisis (Elsubbaugh et al., 2004; Veil, 2011) or cultural readjustment after a crisis (Turner, 1976; Elliott & Smith, 2006).

The crisis management studies investigated the learning component in the final stage (Fink, 1986; Herrero & Pratt, 1996; Mitroff, 2005; Jaques, 2007). Hence, any knowledge or change would occur as post-crisis learning. However, the cultural adjustment would persist if the organisations learn throughout the crisis cycle (Veil, 2011; Deverell, 2012) not post-crisis. Deverell (2012) stated that there is ample opportunity to learn throughout the crisis stages and no evidence showed that an earlier crisis experience would provide effective future crisis response. Senge’s model of organisational learning (1990) addressed the macro and micro barriers existing in the organisational culture.

Here, the researchers focused on the Malaysian hotel industry. Tourism is an important economic sector (World Tourism Organisation report 2009) as it provides employment, alleviates poverty and ensures regional development (De Sausmares, 2007). However, this sector is prone to adverse effects resulting from the country’s social and economic status. The hotel industry was more prone to crises (Byrd, 2007; Wang & Ritchie, 2010). Since it was correlated with other industries, any crisis affected the complete supply chain (Faulkner, 2001; Wang 2009).

Surprisingly, the hotel management was unprepared for crises and failed to recognise the importance of a proactive crisis management (Wang & Ritchie, 2010). None of the tourismrelated studies did not investigate the proactive crisis management (Pforr & Hosie, 2009; Wang & Ritchie, 2013; Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015). An earlier review assessed the hotel industryrelated crisis management studies and noted that they focused only on the crisis response or recovery. This highlighted their ignorance regarding the significance of the proactive crisis management approach (Wang & Ritchie 2010). Combination of a high market vulnerability and low crisis preparedness was alarming, and hence, it is important to investigate crisis management.

The existing studies assessed the disaster and crisis response and used reactive instead of proactive crisis management. The Malaysian tourism industry contributes to its economy (Bhuiyan et al., 2013; Mazumder et al., 2009) and could help the country acquire a developed nation status (Malaysian Hospitality Valuation Service Report 2015). One major strategy includes increasing the no. of 4 and 5-star hotels in Malaysia (Bhuiyan et al., 2013; Mosbah & Al Khuja, 2014). However, use of only a quantitative measure is inadequate and the industry needs to proactively face all crises and become sustainable. Evidence showed that the Malaysian hoteliers use an orthodox approach, are unprepared for a crisis, and relinquish all responsibility to the government (de Sausmarez 2007b; AlBattat and MatSom 2014).

To summarise, this study was based on the Malaysian hotel industry. The following research questions were formulated: 1) how can organisational culture affect the crisis management practices and strategies at various crises stages? 2) Which organisational cultural barriers affect the crisis management practices? 3) Which organisational learning roles can be used as a potential mechanism for overcoming cultural barriers?

Literature Review

Crisis and Crisis Management

An organisational crisis is a low probability, high-impact event that threatens the organisation’s viability. It is characterised by the ambiguity of cause, effect, and means of resolution, and the belief that decisions must be made swiftly (Pearson & Clair, 1998). Crises can affect areas like finance, technology, social science, politics, military and economics (Shrivastava, 1992; Pearson & Clair, 1998). The early crisis theorists viewed crisis as a threat and described it using negative connotations (Hermann, 1963; Rosenthal et al., 1989). Some researchers (Mishra, 1996; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Robert & Lajtha, 2002; Jaques, 2010; Alas & Gao, 2011; Crandall et al., 2013) were optimistic and considered crises as good opportunities.

Pearson & Clair (1998) defined crisis management as a systematic attempt made by the organisational members and external stakeholders to avert crises or effectively manage the occurring crises. This indicated that crisis can be systematically managed after using the detecting, planning, preparing and preventing techniques. Secondly, crisis prevention highlighted the significance of proactive crisis management. Thirdly, it acknowledged the fact that a crisis cannot be avoided. Overdependence on the prevention efforts would expose organisations to new crises (Boin, 2004), hence, the organisations must balance their proactive and reactive efforts. Fourthly, the proactive or reactive crisis management efforts must be systemised, and not include any haphazard activities. Fifthly, these crisis management efforts must involve the organisational members and their interaction with the stakeholders’ throughout a crisis. This highlighted the significance of crisis communication as a subset of crisis management.

Crisis Management Models

Crisis management models function as frameworks that help the organisations handle crises, and comprise of the prevention, preparation, response and revision components (Fink, 1986; Smith, 1990; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Herrero & Pratt, 1996; Crandall et al., 2013). The prevention and preparation functions are addressed before a crisis, response during a crisis, and revision, post-crisis. These models differ based on the crisis definitions described by scholars, scholars’ discipline, and scholars’ perspectives.

The crisis management models were based on the crisis life cycle, which were adopted from biological models and showed a correlation between the crisis and an organism, as both of them pass through birth, growth, maturity and death (Herrero & Pratt, 1996). This analogy helps the crisis researchers study the evolution and stages of a crisis (Crandall et al., 2013). However, these models were linear, indicating that all events take place sequentially (Jaques, 2007). The popular life cycle models include a 3-stage model, Smith’s 3-stage model (1990), Fink’s 4-stage model (1986), Herrero and Pratt’s 4- stage model (1996), Jacques’ relational 4-stage model (2007; 2010), a 4-stage model by Crandall et al. (2013) and a 5-stage model (Mitroff et al., 1988; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993). Out of the above-mentioned models, the 4-stage models by Jaques (2007); Crandall et al. (2013) are popular.

Other crisis models adopted a linear approach that indicated that all stages were independent. Jacques (2007) showed that all crisis stages were interrelated, and constructed a relational crisis management model, based on an integrative approach, for highlighting the dynamic nature and complexity of the organisational crises. Crandall’s model (Crandall et al., 2013) could handle the crisis stages within the organisation and external environment. This model added another crisis dimension, i.e., the external landscape that can fill the gap in the crisis management models. Some non-life cycle management models were also proposed, like the Pearson and Clair’s model (1998) and Burnett’s model (1998). Literature analysis showed that the life cycle crisis models were generally used for crisis management.

Organisational Culture and Crisis Management

According to Pettigrew (1979), the organisational culture consisted of symbols, language, ideology, beliefs, rituals and myths. Hence, he investigated the organisational culture using an integrative perspective. Organisational culture improves the functioning of an organisation and affects organisational activities (Schein, 1990; Schraeder & Self, 2003; Hofstede, 2010). It signified a socially-constructed system and united the people within an organisation (Schraeder et al., 2005). Schein (1990) defined organisational culture as a pattern of basic assumption and proposed an organisational culture model with 3 levels, i.e., artefacts, espoused values, and underlying assumptions.

Researchers like Turner (1976) prioritised finding formal and technical solutions during a crisis and neglected the significance of organisational culture in crisis management. Mitroff et al. 1988; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993 stated that a crisis-prepared organisation effectively manages its crisis. The organisational culture determined if the organisation was crisis-prepared or crisisprone. It either escalates a crisis or helps the organisation prepare, respond, cope and learn during a crisis (Deverell & Olsson, 2010; Veil, 2011). Table 1 describes the barriers affecting crisis management.

| Table 1: Organisational Cultural Barriers Affecting Crisis Management | ||

| Crisis stage | Cultural barriers | Examples of Supporting Works |

| Pre Crisis | Barriers for adopting crisis management program: Denial, Idealisation, Disavowal and Fixation. | (Mitroff et al., 1988), (Pearson & Mitroff, 1993), (Elliott et al., 2000). |

| Barriers to recognise the warning signals: Classification With Experience, Reliance On Success, and Trained Mindlessness. | (Veil, 2011) | |

| Crisis Stage | Rigid culture and ineffective communication, information gathering and sharing difficulty, blocking the flow of bad or unpleasant information, and information distortion. | (Smallman & Weir, 1999), (Coombs, 2014) |

| Post Crisis | Barriers for holding learning Process: Blame culture and scapegoating | (Elliott et al., 2000), (Smith & Elliott, 2007), (Catino, 2008) |

Organisational Learning and Crisis Management

Organisational learning (Argyris & Schon, 1978) facilitates and enhances quick response systems (Dodgson 1993; Garvin et al., 2008; Senge 2014). It includes cognitive (Shrivastava, 1983) and behavioural approaches (Swieringa & Wierdsma, 1992). Cook & Yanow (1993) described another cultural approach for highlighting the importance of culture in organisational learning. The organisational learning models include the first loop and double loop learning (Argyris & Schon 1978). The first loop adjusts the actions based on the problem’s feedback, while the double loop extends this process by adjusting the governing values and basic assumptions. These models influenced other models (Kim, 1993; Common, 2004). Senge (2014) introduced a model with 5 disciplines, i.e., shared vision, mental models, personal mastery, team learning and systems thinking, for building an organisation and overcoming the disabilities.

Mitroff incorporated learning in his crisis management model (Mitroff et al., 1988; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Mitroff, 2005). Generally, learning was the last step in any crisis management model since the earlier studies used a pervasive reactive crisis approach. This indicates that any change in the organisational culture occurs during the post-crisis learning. Smith & Elliott (2007) introduced 3 learning concepts, i.e., learning for a crisis, learning as a crisis, and learning from a crisis. According to Deverell (2012), the traditional learning technique showed a deficient response to crises. Veil (2011) incorporated the concepts of single, double and triple loop learning in crisis management. He stated that the organisations must implement a ‘Mindful Learning Model’ for adapting to the cultural changes.

Some studies investigated the role of organisational learning in crisis preparedness and crisis management (de Sausmarez, 2007b; Wang, 2008; Veil, 2011). Traditionally, learning was the last stage that was studied, and the earlier studies did not present any learning processes for helping the organisations face the crises (Deverell, 2012; Antonacopoulou & Sheaffer, 2014). One need to reassess the role of learning in crisis management, hence, Senge's (2014) model could bridge these gaps. This model can help in building the organisational dynamic capabilities, as it used the organisational cultural barriers as opportunities for generating a flexible crisis management program. Thereafter, they do not rely on the prewritten procedures during a crisis and can handle any issues.

To summarise, the earlier researchers believed that a crisis is negative and should be avoided; hence, they focused on the reactive instead of the proactive technique. This is not recommended since crises are inevitable, unpredictable and complex. Several crisis management models were based on the perspective that the crisis management model was a linear sequential process, and disregarded the fact that all crisis stages are interrelated. The organisational culture played a vital role as it facilitated/ inhibited the crisis management practices. The existing studies are fragmented (James et al., 2011; Buchanan & Denyer, 2013; Bundy et al., 2017).

Organisational learning was considered the last stage during crisis management and did not build crisis-resilient organisations. Hence, the organisations need to embrace learning throughout all crisis stages (Deverell, 2012; Antonacopoulou & Sheaffer, 2014). Such limitations hinder the understanding of crisis and disable the alignment of organisational culture and learning. This study attempted to answer all questions and develop an integrated crisis management model.

Methodology

Study Context

This study focused on the Malaysian hotel industry. Due to the many natural and cultural tourist attractions, Malaysia has become a popular travel destination (United Nation of World Tourism Organisation 2014). Its tourism sector is governed by the Ministry of Malaysian Tourism and Culture who develops various policies. In 2017, 26 million tourists visited Malaysia, generating MYR82 billion (www.tourism.gov.my). The hotel industry supports tourism in Malaysia. The industrial bodies that control the affairs of all hoteliers include the Malaysian Association of Hotels (MAH) and the Malaysian Association of Hotel Owners (MAHO). Malaysia had to face many crises like the Malaysian airlines, which affected the reputation of the Malaysian tourism industry.

Research Approach

The researchers used an exploratory research design based on the interpretivism philosophical position. A multiple case study approach (Yin, 2009) was applied for studying the activities of the selected organisations. This case study strategy also offers an intensive and exhaustive knowledge regarding a particular topic (Saunders, 2011).

Sampling

Here, the unit of analysis was an organisation (Malaysian hotels). Purposeful sampling, based on a maximal variation sampling strategy (Creswell, 2002) was used for selecting the hotels and participants (Merriam, 2015).

This study focused on the hotels, with at least a 3-star rating, from Kuala Lumpur and Selangor. The low-star hotels would not be able to offer any useful data. The sampling frame comprised of 156 three, four and five-star hotels, which were registered with the Ministry of Malaysian Tourism and Culture (MOTAC). Finally, 4 hotels were chosen (Yin, 2009), i.e., 3 locally-owned hotels (a 3-, 4- and 5-star hotel, each), and a 5- star international chain hotel. This number fulfilled the guidelines presented by the qualitative/case research scholars (Yin, 2009; Starman, 2013; Lewis, 2015; Merriam, 2015). 3 categories of people, i.e., hotel managers, employees and crisis managers/personnel, were chosen. 17 participants represented the hotel’s perspective. A snowballing strategy was used for interviewing the industry experts and authorities. 8 experts were included, from MAH (2), MOTAC (5), and MAHO (1). These individuals held vital decision- making positions and had decades of experience in the hotel and tourism industries.

Data Collection and Analysis

The researchers conducted in-depth, semi-structured interviews and the interview protocols were based on the guidelines described by Mason (2002). A different question set was prepared for various participants (like top management, employees, crisis managers, industry experts /authorities).

This study was conducted in two phases: Phase 1 included the hotels and Phase 2 included the expert panel. Many interviews were conducted at the interviewees’ work premises, lasting 30-90 mins, which were audio-recorded with permission. The data reached a saturation point (Mason, 2002) after 25 interviews. For triangulation, the field notes and relevant documents like the hotels’ crisis plans, organisational charts, websites, and media news were gathered. The interviews were transcribed after every session. Data was analysed using the thematic content analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Saldaña, 2015), using the Nvivo software and manual analysis.

Findings

The data analysis presented many themes, which were organised into 3 categories. The cross-case data was also summarised. To reiterate, the data was based on 25 interviews, field notes, relevant documents and websites.

Four of the selected hotels were locally-owned, with the following profile. The 3-star hotel was located on a university campus, with 4 years in service, had 56 rooms and <50 employees. The 4-star hotel had 20 years in service, with 204 rooms and 250 employees. The 5- star hotel had 19 years in business, with 341 rooms and 400 employees. The international 5-star hotel had 561 rooms and >500 employees. All local hotels showed low pre-crisis planning. Commitment and preparation for crisis management (presence of a crisis unit, crisis plan, and warning signal mechanisms) increased with their star status and international status.

Role of Organisational Culture at a Pre-Crisis Stage (Signal Detection, Prevention and Planning)

Organisational culture played a vital role in the pre-crisis stage. Table 2 presents the faulty assumptions made by all cases regarding their hotels, external environment, threats and crises, which prevented them from adopting better crisis management activities.

| Table 2 : Faulty Assumptions That Prevented The Adoption Of Crisis Management And Narrative Examples | |

| Faulty assumptions about organisation | Narrative Examples |

| The location will save us | As long as we are in the university area we are safe. (Laugh) we are not like five star hotel, they have to worry, and tighten their security.” (P02, human resource manager, 3-star hotel). |

| Crisis will not happen in a small hotel | We are just three stars hotel (P03, operation manager, 3- star hotel). Terrors usually affect large organisation with huge amount of money, our hotel is not that big (P05, chef, 3-star hotel) |

| Crisis management requires extra resources | Not that many resources available to devote for a specific crisis management (P03, operation manager, 3-star hotel). I believe that if we invest in insurance for staff and guests is better. Resources are limited, we need to invest wisely (P12, general manager, 5-star hotel). |

| Faulty assumptions regarding external environment | Narrative Examples |

| Crisis management is government’s responsibility | Government should take a part of responsibility (P15, security manager, 5-star international hotel). Yes, usually if something like natural disaster happens and it’s beyond our control anyway, so government assists us. Other cases which result because of mistakes we have to handle by ourselves (P07, sales manager, 4-star hotel). |

| Faulty assumption regarding external environment |

Narrative Examples |

| The country is safe | At least in comparison with other countries Malaysia is safer (P12, general manager, 5-star hotel). Generally Malaysia is safe (P05, chef, 3-star hotel). Terrors are targeting the unstable countries where there is political and social conflict, here we live in harmony (P15, security manager, 5-star international hotel) |

| There are no regulations | We have compulsory regulation regarding fire system, evacuation plan and CCTV, I think if crisis management is necessary for our business, specific regulations should be in place (P04, hotel manager, 3-star hotel) • “There is no specific regulation for crisis planning from authoritative parties (P25, executive director, MAHO) |

| Faulty assumption regarding threats and crises | Narrative Examples |

| Some crisis will not happen here | I think that five stars hotel should worry about terrorism and kidnapping, since it usually happens there, small business are not targeted (P01, accountant, 3-star hotel) |

| Crisis happens by fate | Actually this depends on the crisis type. If it is a natural disaster then yes it is fate…we can do nothing to prevent. (P03, operation manager, 3-star hotel). Yes we can blame fate as well sometimes, natural disaster is the most common crisis, but also other crises can be referred to fate like fire especially when it occurs due to technical faults” (P10, general manager, 4-star hotel). Yes I believe that everything that happens is our fate and we have to believe in Qada and Qadar (i.e. God’s fate) and accept it (P14, security manager, 5-star hotel). |

All hotels used defensive mechanisms. Compared to the 5-star hotel, the 3-star hotel relied heavily on rationalisation for justifying the non-adoption of crisis management. They used their location, size and fate as a rationale for ignoring the crisis. Furthermore, all interviewees were Muslims and a total belief and acceptance of God’s fate indicates practising Muslims. The 4 cases shared a belief that Malaysia was safe and assigned the responsibility of crisis management to the hotel associations and government. A government authority (P21, deputy director, MOTAC) attributed this attitude to the industry’s belief that governmental support was available. He stated that: (the) hotel industry (is) not working independently. I don’t think they have considered this (crisis) issue yet, which is related to mentality and beliefs (that the government will help).

Organisational culture played a vital role in detecting and blocking the warning signals for crises. The results indicated Schein’s 3 levels of culture. A prominent example was the whistleblowing policy. The 4-star and 5-star international hotels tolerated unpleasant news better than the other hotels due to their whistleblowing policies. Presence of this policy (i.e., Schein’s artefact) showed that the hotels cared to be informed (i.e. espoused values), and the employees believed that they would be fairly treated (i.e., basic assumptions). However, the results showed the presence of a blaming culture, scapegoating culture and turnover culture, which blocked the crisis warning signals. A MAHO representative (P25, executive director, MAHO) regarded the turnover culture as critical. He remarked: I have >40 years’ experience in the hospitality industry and I believe that the turnover is a crisis. Furthermore, organisational bureaucracy and rigid structure were also noted. One participant remarked: Every person in a department has a workload, and it is impossible to observe other departments’ problem since they are constrained by their experience and knowledge. Even if some (problems are) recognised, the management is not notified, since the rigid structure of the departments disallows interference (P08, human resource manager, 4-star hotel).

Role of Organisational Culture at Crisis Stage (Damage Containment and Recovery)

The organisational culture affected crisis management activities during a crisis, which highlighted the importance of communication for swift decision-making. The respondents admitted that organisational bureaucracy slowed them. Similar observations were made by the 5- star hotel: The bureaucracy is overriding, some decisions are time-consuming or tedious, which, if shortened, would help in handling the guests effectively. Every minute matters in a crisis (P16, frontline worker, 5-star international hotel).

The turnover culture also affected organisational activities. The respondents stated that employee engagement with crisis management practices was based on their service length and intention to stay/leave. Since a crisis required communication and information-sharing, the employees that did not feel affiliated with their organisation were unwilling to communicate. Hence, they distorted/ withheld information or blocked the flow of negative information. Interviews with the MAH representative highlighted the prevalence of this turnover culture (caused by a large temporary staff or low financial/ nonfinancial benefits) in the Malaysian hotel industry.

Furthermore, people conceal information for avoiding liability, which led to a blaming culture. This culture is noted amongst people who are reluctant to detect or transmit warning signs because they fear liability. One respondent remarked: People will sweep the matter under the rug because they are worried about getting into trouble if something happens (P03, operation manager, 3-star hotel).

Role of Organisational Culture at the Post-Crisis Stage

Results indicated that the 4 cases conducted investigations after a critical incident like fire or theft, but failed to include this knowledge into their current practice. They implemented single loop learning, like altering the current procedures, but disregarded the organisational core paradigm. Findings indicated that the organisational culture, based on rigid core beliefs, inhibited the adoption of double loop learning. The MAH experts remarked that: We need to improve the way the hotels learn. Single loop learning is dominant since the norms (were) developed for warning the people that they must not oppose the hotel policies, regulations and goals, which restricted an upward communication (P23, CEO, MAH). However, the 5-star hotel implemented double loop learning.

The findings indicated that the hotels used defence mechanisms that blocked the learning process. Managers don’t find crisis management training and seminars useful. Hence, they prefer to invest in other areas. They refuse or disregard their vulnerability to crises and are complacent (P24, MAH). Scapegoating, blame and turnover culture inhibited the learning process. The hotels were reluctant to conduct staff training due to a high staff turnover: Spending money on training crisis management programs decreases turnover number (P17, human resource, 5-star international hotel).

Furthermore, the findings showed a lack of system thinking in the hotel industry. A MAH respondent stated: The hotel industry is interconnected with other sectors like the airlines, transportation and travel agency. Changes in these industries would extend and affect the hotel industry. Last year, due to the Malaysian airline incidents, there was a decrease in the no. of people arriving in Malaysia. Hotel managers must be aware of all these issues (P24, general manager, MAH). A MOTAC respondent stated that: People (in the hotel industry) usually focus on their jobs, and disregard the effect of their job on others. If the outcomes are disappointing, they do not understand why (P19, executive officer, MOTAC). Another MOTAC employee emphasised the importance of team learning and stated that constant dialogues were needed for double loop learning, which could help the crisis management team rectify the faulty assumptions.

Turnover Impact on Crisis Management

Results showed that the turnover culture inhibited the crisis management. The MAH respondent stated that a high employee turnover prevented the hotels from employing good staff. One expert stated that: (turnover is) a big challenge for the hotel industry, while another mentioned that: “Out of the 150 employees, only 100 will remain for the next 3 months. In the hotel industry, the staff moves around to derive experience and more pay. (P13, human resource, 5-star hotel). One employee stated that: This is the third hotel I worked in. I worked for a maximum of 2 years at the same place. Now I am looking for a better offer! Table 4 presents the sub-themes derived from the findings.

| Table 3: Cross-Case Analysis Of The Effect Of The Organisational Culture On Crisis Stages | |

| Crisis Stage | Influence of Organisational Culture and Cultural Barriers on Crisis Management |

| Before crisis | As suggested from the findings, the 3-star hotel was the least prepared hotel. The findings suggested that the 3-star hotel used defensive mechanisms to justify not adopting crisis management. 4-star sand 5-star hotels took some initiative for crisis planning. The evidence from the study suggested that both hotels used defensive mechanisms to justify their ignorance of crisis management. However, compared to the 3-star hotel the use of defensive mechanism was less. 5-star international hotel was the most prepared hotel and used minimal amount of defensive mechanisms. Further findings suggest that blaming culture and ineffective communication, and turnover culture all influenced in detecting crisis warning signals in all four cases. |

| During crisis | The organisational chart from the hotels indicated that the organisational structure of the hotels hindered the decision- making during crisis as reflected by ineffective communication and difficulty in sharing information. However it is worth mentioning that the 3-star hotel had a flatter structure due to its size (number of rooms) and number of staff. This study could not capture any significant evidence to support the influence of the flatter structure on crisis management in 3-star hotel. Further findings suggest that blaming culture, turnover culture, and defensive mechanisms all influenced the crisis management practices during crisis in all four cases. |

| Post crisis | The overall findings suggest the dominant approach for learning in 3-star hotel, 4-star hotel, and 5-star hotel is single loop learning, while in 5-star international hotel there is more attention to double loop learning. The findings suggest that the rigid core beliefs were responsible for the adoption of single loop learning in the above mentioned hotels. Further findings suggest that blaming culture, turnover culture, and rigid structure all influenced the crisis management practices after crisis in all cases. |

| Table 4: Effect Of Turnover Culture On Crisis Management And Narrative Examples | |

| Sub-themes | Narrative examples |

| Turnover culture builds silence and irresponsible workforce | Sometimes I see negative behaviour of a staff member towards a guest, but I never tell the management. Why should I get in trouble? You know this is the third hotel I worked for during the last five years. In all hotels I worked for I just did my work” (P13, Front office executive, 5-star hotel) I never tried to tell the management about the negative comments from reviewers on the internet, I think they have their method to see the online review, and as a part time worker no one asks me about such issues, honestly my concern is to finish my shift... that’s all” (P05, Chief, 3 -star hotel) |

| Turnover culture hinders the healthy communication amongst the workforce | During my work experience I faced several incidents that needed investigation. I noticed that the part time and new employees are less cooperative in the investigation than the employees who have been with us for a long time. I think that those have the intention to leave soon so they don’t feel any commitment towards the hotel, they are not truly engaged and involved (P15, security manager, 5-star international hotel) |

| Turnover culture builds mistrust environment | Manager not only tells us what to do but even, how to do. As staff in this hotel we are directed task by task. I don’t think the management trusts their staff and gives them autonomy, do you know why this is….because of turnover. It is ironic management cannot give autonomy and they know you may leave soon (P08, human resource manager, 4- star hotel) I prefer not to report any accident with guests to the management, and they decide what is the appropriate actions….this is the safest way to avoid punishment (P13, front line, 5-star hotel) |

| Turnover culture disrupts training and learning | For me I cannot expend money into training projects which will not benefit the hotel. We like to pay for training the staff that is likely to stay with us. (P17, human resource, 5-star international hotel) |

The turnover culture affected the way a crisis was viewed and managed, as it created a silent and irresponsible workforce. If the employees believed their tenure was temporary, it could affect their daily activities including crisis management. In the hotel industry, the guest complaints and reviews are an important signal of crisis. However, temporary staff neglects these signals. Secondly, the turnover culture hindered communication between all the personnel. Since the employees did not feel affiliated to their organisation, they did not share information or communicate effectively, and withheld or blocked the flow of unpleasant information.

Thirdly, a high turnover decreased the trust required for effective crisis management, which increased the scapegoating and blaming behaviour. This mistrust affected communication, centralised the decision-making and rigid authority. Finally, the turnover culture negatively affected the learning process, and resilience required for crisis management. The high turnover affected the training since the managers were reluctant to train staff due to the perception that the employees would leave their jobs. Learning helps an organisation derive knowledge for preventing such crises, changing or improving the detection of warning signals, recovery and damage containment.

Cross-Case Analysis and Summary of Findings

It was seen that the organisational culture affected the crisis stages. The organisational cultural barriers were of 5 types; rigid core beliefs; faulty assumption; Rigid organisational structure; blaming or scapegoating culture, and turnover culture. Cross-case analysis (Table 3) highlighted some similarities and differences between the 4 hotels with regards to crisis management practices and effect of organisational culture on crisis management.

Discussion

This study showed that the organisational cultural barriers that affected the crisis management practices were interrelated. This study attempted to answer 2 questions: 1) how does organisational culture affect crisis management practices at different crisis stages? 2) Which organisational cultural barriers affect crisis management practices?

This study described the problems affecting the Malaysian hotel industry. A lack of proactive preparation towards crisis was observed (Ritchie et al., 2011; AlBattat and MatSom 2014; Alonso-Almeida et al., 2015), even in Malaysia. The results indicated that the hotel star rating and their local vs. international status affected their commitment towards crisis. The hotels with a higher star rating and international status were more committed towards crisis management than the local hotels.

This study highlighted the effect of organisational culture on crisis management, like earlier studies (Fink, 1986; Mitroff et al., 1988; Smallman & Weir, 1999; Deverell & Olsson, 2010; Veil, 2011). The selected cases presented the negative effect of the organisational culture on crisis management. The hotel management used many faulty assumptions and reasons like location, size, government’s role, and lack of resources, for not adopting the crisis management programs. Out of these, the assumption that ‘crisis is fated’ reflected the attitude of many Malaysian Muslims.

This study provided empirical evidence which indicated that the organisational cultural barriers were not exclusive to a specific crisis stage but occurred throughout all stages. As shown earlier (Smallman & Weir, 1999; Elliott et al., 2000; Catino, 2008; Veil, 2011), the barriers affected crisis management, i.e., faulty assumptions regarding a crisis, which increased their unawareness regarding the importance of crisis management program; rigid organisational structure which affected the communication throughout the crisis stages, blaming or scapegoating culture, and a turnover culture. All faulty assumptions, related to the impact or occurrence of the crisis, were similar to those described earlier. Denial was an important organisational cultural factor which hindered crisis management (Mitroff et al., 1988; Pearson & Mitroff, 1993; Mitroff, 2005). Results indicated that organisational learning helped in overcoming the organisational cultural barriers. Senge’s model could help the organisations minimise the negative culture and foster positive ones. Researchers stated that team-learning dialogues between the staff and management improved the relationship, trust, and system thinking, which helped in handling crises.

This study presented a novel organisational cultural barrier, i.e. turnover culture, affecting the hotel industry (Yang, 2008; Davidson et al., 2010; AlBattat & Som, 2013) due to low pay and a lack of developmental opportunities (Deery & Iverson 1996). Iverson & Deery (1997) stated that there is a normative belief amongst the workers (in the hotel industry) that a high turnover is acceptable. Abelson (1987) defined the turnover culture as the systematic pattern of shared cognitions by organisational or subunit members that influence decisions regarding job movement. The turnover culture was associated with the employee’s intention to leave (Deery & Iverson, 1996) and decreased the organisational commitment (Iverson & Deery, 1997; Balkan et al., 2014), communication (Mueller & Price, 1989) and trust (Serin & Balkan, 2014). The turnover culture inhibited crisis management practices, developed a silent and irresponsible workforce, and increased mistrust, which inhibited the detection of looming crises, and hindered communication. Turnover culture also disrupted crisis learning and training.

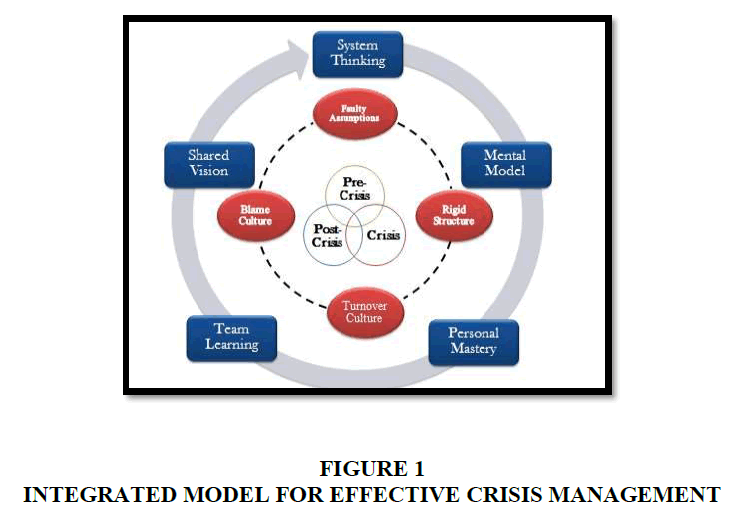

Figure 1 presents an integrated model that helped in an effective crisis management. The concepts of crisis management, organisational culture and organisational learning were integrated into a circular, single holistic model (Mitroff, 2005; Jacques, 2007, 2010; Senge, 2014). It emphasised the dynamic nature of the crises and a non-linear process of crisis management. It also showed the correlation between the crisis stages which was neglected in the earlier models. All the organisational cultural barriers showed a combined effect throughout the crisis stages. Senge’s five disciplines of learning helped the organisations overcome the cultural barriers and increased their awareness, which helped in crisis management. This integrated model addressed the knowledge fragmentation and proposed a holistic view for researching and practising crisis management. This study introduced an empirically-driven crisis management framework.

This study investigated the role played by the organisational culture and cultural barriers on crisis management, by focusing on the Malaysian hotel industry. This study provoked a new thinking paradigm by embracing a dynamic and nonlinear approach while studying crisis. It highlighted the reciprocal effect of the organisational cultural barriers throughout the crisis stages. This study showed that turnover culture negatively affected crisis management practices in the hotel industry, and proposed an integrated crisis management model.

Conclusion, Limitations And Future Research

This study investigated the role played by the organisational culture and cultural barriers on crisis management, by focusing on the Malaysian hotel industry. This study provoked a new thinking paradigm by embracing a dynamic and nonlinear approach while studying crisis. It highlighted the reciprocal effect of the organisational cultural barriers throughout the crisis stages. This study showed that turnover culture negatively affected crisis management practices in the hotel industry, and proposed an integrated crisis management model.

This study showed that the Malaysian hotel industry lacked a proactive crisis management program, which was linked to the background of the hotels, spiritual beliefs of the participants, and the decades-old subsidy policies of the Malaysian government. Furthermore, the researchers stated that improving crisis management activities could significantly benefit the stakeholders in the Malaysian hotel industry and they could learn how to foster the right organisational culture for improving their crisis management.

The major limitations of this study were its sample size, and obtaining cooperation from the hotels. One of the researchers was non-Malaysian, and due to the language barrier, the sample selection in every hotel was restricted to the English-speaking individuals. The cultural differences could affect the communication dynamics during interviews. However, the researchers took utmost care to reduce these issues, since the other researcher was Malaysian and supervised the study. Due to the above-mentioned issues, the no. of hotel representatives was fewer than expected. Though the data was supplemented by interviewing the industry experts, examining important documents, and fulfilling the data saturation requirements, the sample size could affect the findings.

This study used a qualitative research approach. Future studies must adopt a different methodological approach with a larger sample size. Though national culture affects the organisational culture, it was beyond the focus of this study. In future, other researchers must investigate the effect of national culture on the organisational cultural barriers for improving crisis management. Since this study was conducted in Malaysia, the results could be used for comparing crisis management activities implemented in the Asian and Western countries. Future research must compare the findings obtained from the international chain hotels in Malaysia and other countries.

References

- Hart, P., & Sundelius, B. (2013). Crisis management revisited: A new agenda for research, training and capacity building within Europe. Cooperation and Conflict, 48(3), 444-461.

- Abelson, M.A. (1987). Examination of avoidable and unavoidable turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72(3), 382.

- Alas, R., & Gao, J. (2011). Crisis management in Chinese organizations: Benefiting from the changes: Springer.

- AlBattat, A.R., & MatSom, A.P. (2014). Emergency planning and disaster recovery in Malaysian hospitality industry. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 144, 45-53.

- AlBattat, A.R.S., & Som, A.P.M. (2013). Employee dissatisfaction and turnover crises in the Malaysian hospitality industry. International Journal of Business and Management, 8(5), 62.

- Alexander, D.E. (2016). The game changes: Disaster prevention and management after a quarter of a century. Disaster Prevention and Management, 25(1), 2-10.

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M., Bremser, K., & Llach, J. (2015). Proactive and reactive strategies deployed by restaurants in times of crisis: Effects on capabilities, organization and competitive advantage. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(7), 1641-1661.

- Antonacopoulou, E.P., & Sheaffer, Z. (2014). Learning in crisis: Rethinking the relationship between organizational learning and crisis management. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(1), 5-21.

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action approach. Reading, MA: Addision Wesley.

- Balkan, M.O., Serin, A.E., & Soran, S. (2014). The relationship between trust, turnover intentions and emotions: An application. European Scientific Journal, 10(2).

- Bhuiyan, M.A.H., Siwar, C., & Ismail, S.M. (2013). Tourism development in Malaysia from the perspective of development plans. Asian Social Science, 9(9), 11.

- Boin, A. (2004). Lessons from crisis research. International Studies Review, 6(1), 165-194.

- Buchanan, D.A., & Denyer, D. (2013). Researching tomorrow's crisis: Methodological innovations and wider implications. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 205-224.

- Bundy, J., Pfarrer, M.D., Short, C.E., & Coombs, W.T. (2017). Crises and crisis management: Integration, interpretation and research development. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1661-1692.

- Burnett, J.J. (1998). A strategic approach to managing crises. Public Relations Review, 24(4), 475-488.

- Byrd, E.T. (2007). Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review, 62(2), 6-13.

- Catino, M. (2008). A review of literature: Individual blame vs. organizational function logics in accident analysis. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 16(1), 53-62.

- Common, R. (2004). Organisational learning in a political environment: Improving policy-making in UK government. Policy studies, 25(1), 35-49.

- Cook, S.D., & Yanow, D. (1993). Culture and organizational learning. Journal of Management Inquiry, 2(4), 373-390.

- Coombs, W.T. (2014). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing and responding: Sage Publications.

- Crandall, W.R., Parnell, J.A., & Spillan, J.E. (2013). Crisis management: Leading in the new strategy landscape: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J.W. (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative: Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Davidson, M.C., Timo, N., & Wang, Y. (2010). How much does labour turnover cost? A case study of Australian four-and five-star hotels. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(4), 451-466.

- De Sausmarez, N. (2007a). Crisis management, tourism and sustainability: The role of indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(6), 700-714.

- De Sausmarez, N. (2007b). The potential for tourism in post-crisis recovery: Lessons from Malaysia's experience of the Asian financial crisis. Asia Pacific Business Review, 13(2), 277-299.

- Deery, M.A., & Iverson, R. (1996). Enhancing productivity: Intervention strategies for employee turnover. Productivity Management in Hospitality and Tourism, 68-95.

- Deverell, E. (2012). Is best practice always the best? Learning to become better crisis managers. Journal of Critical Incident Analysis, 3(1), 26-40.

- Deverell, E., & Olsson, E.K. (2010). Organizational culture effects on strategy and adaptability in crisis management. Risk Management, 12(2), 116-134.

- Dodgson, M. (1993). Organizational learning: a review of some literatures. Organization Studies, 14(3), 375-394.

- Elliott, D., & Smith, D. (2006). Cultural readjustment after crisis: Regulation and learning from crisis within the UK soccer industry. Journal of Management Studies, 43(2), 289-317.

- Elliott, D., Smith, D., & McGuinnes, M. (2000). Exploring the failure to learn: Crises and the barriers to learning. Review of Business, 21(3/4), 17.

- Elsubbaugh, S., Fildes, R., & Rose, M.B. (2004). Preparation for crisis management: A proposed model and empirical evidence. Journal of contingencies and crisis management, 12(3), 112-127.

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism management, 22(2), 135-147.

- Fink, S. (1986). Crisis management: Planning for the inevitable: American Management Association.

- Garvin, D.A., Edmondson, A.C., & Gino, F. (2008). Is yours a learning organization? Harvard business review, 86(3), 109.

- Hermann, C.F. (1963). Some consequences of crisis which limit the viability of organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 61-82.

- Herrero, A.G., & Pratt, C.B. (1996). An integrated symmetrical model for crisis-communications management. Journal of Public Relations Research, 8(2), 79- 105.

- Hofstede, G. (2010). Geert hofstede. National cultural dimensions.

- Iverson, R.D., & Deery, M. (1997). Turnover culture in the hospitality industry. Human Resource Management Journal, 7(4), 71-82.

- James, E.H., Wooten, L.P., & Dushek, K. (2011). Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 455-493.

- Jaques, T. (2007). Issue management and crisis management: An integrated, non-linear, relational construct. Public Relations Review, 33(2), 147-157.

- Jaques, T. (2010). Reshaping crisis management: The challenge for organizational design. Organization Development Journal, 28(1), 9.

- Jaques, T. (2014). Issue and crisis management: Exploring issues, crises, risk and reputation: Oxford University Press South Melbourne.

- Kim, D.H. (1993). A framework and methodology for linking individual and organizational learning: Applications in TQM and product development. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Lalonde, C. (2007). Crisis management and organizational development: Towards the conception of a learning model in crisis management. Organization Development Journal, 25(1), 17.

- Lewis, S. (2015). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Health Promotion Practice, 16(4), 473-475.

- Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative interviewing: Asking, listening and interpreting. Qualitative Research in Action, 6, 225-241.

- Mazumder, M.N.H., Ahmed, E.M., & Al-Amin, A.Q. (2009). Does tourism contribute significantly to the Malaysian economy? Multiplier analysis using IO technique. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(7), 146.

- Merriam, S.B. (2015). Qualitative research: Designing, implementing, and publishing a study Handbook of Research on Scholarly Publishing and Research Methods(125-140): IGI Global.

- Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M., Huberman, M.A., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook: sage.

- Mishra, A.K. (1996). Organizational responses to crisis. Trust in organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, 261.

- Mitroff, I.I. (2005). Why some companies emerge stronger and better from a crisis: 7 essential lessons for surviving disaster: AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn.

- Mitroff, I.I., Pauchant, T.C., & Shrivastava, P. (1988). The structure of man-made organizational crises: Conceptual and empirical issues in the development of a general theory of crisis management. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 33(2), 83-107.

- Mosbah, A., & Al Khuja, M.S.A. (2014). A review of tourism development in Malaysia. Euro J Bus and Manage, 6(5), 1-9.

- Mueller, C.W., & Price, J.L. (1989). Some consequences of turnover: A work unit analysis. Human Relations, 42(5), 389-402.

- Pearson, C.M., & Clair, J.A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. Academy of management review, 23(1), 59-76.

- Pearson, C.M., & Mitroff, I.I. (1993). From crisis prone to crisis prepared: A framework for crisis management. The Academy Of Management Executive, 7(1), 48-59.

- Pettigrew, A.M. (1979). On studying organizational cultures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 570-581.

- Pforr, C., & Hosie, P. (2009). Crisis management in the tourism industry: Beating the odds? : Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

- Ritchie, B.W., Bentley, G., Koruth, T., & Wang, J. (2011). Proactive crisis planning: lessons for the accommodation industry. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 11(3), 367-386.

- Robert, B., & Lajtha, C. (2002). A new approach to crisis management. Journal of contingencies and crisis management, 10(4), 181-191.

- Rosenthal, U., Hart, P.T., & Charles, M.T. (1989). The world of crises and crisis management. Coping with crises: The Management of Disasters, Riots and Terrorism, 3-33.

- Sahin, B., Kapucu, N., & Unlu, A. (2008). Perspectives on Crisis Management in European Union Countries: United Kingdom, Spain and Germany.

- Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers: Sage.

- Saunders, M.N. (2011). Research methods for business students, 5/e: Pearson Education India.

- Schein, E.H. (1990). Organizational culture: What it is and how to change it. Human Resource Management in International Firms (56-82): Springer.

- Schraeder, M., & Self, D.R. (2003). Enhancing the success of mergers and acquisitions: An organizational culture perspective. Management Decision, 41(5), 511-522.

- Schraeder, M., Tears, R.S., & Jordan, M.H. (2005). Organizational culture in public sector organizations: Promoting change through training and leading by example. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 26(6), 492-502.

- Senge, P.M. (2014). The fifth discipline fieldbook: Strategies and tools for building a learning organization: Crown Business.

- Serin, A.E., & Balkan, M.O. (2014). Burnout: The effects of demographic factors on staff burnout: An application at public sector. International Business Research, 7(4), 151.

- Shrivastava, P. (1983). A typology of organizational learning systems. Journal of Management Studies, 20(1), 7-28.

- Shrivastava, P. (1992). Bhopal: Anatomy of a crisis: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Smallman, C., & Weir, D. (1999). Communication and cultural distortion during crises. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 8(1), 33-41.

- Smith, D. (1990). Beyond contingency planning: Towards a model of crisis management. Industrial Crisis Quarterly, 4(4), 263-275.

- Smith, D., & Elliott, D. (2006). Key readings in crisis management: Systems and structures for prevention and recovery: Routledge.

- Smith, D., & Elliott, D. (2007). Exploring the barriers to learning from crisis: Organizational learning and crisis. Management Learning, 38(5), 519-538.

- Starman, A.B. (2013). The case study as a type of qualitative research. Journal of Contemporary Educational Studies/Sodobna Pedagogika, 64(1).

- Swieringa, J., & Wierdsma, A. (1992). Becoming a learning organization.

- Topper, B., & Lagadec, P. (2013). Fractal crises–A new path for crisis theory and management. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 21(1), 4-16.

- Turner, B.A. (1976). The organizational and interorganizational development of disasters. Administrative Science Quarterly, 378-397.

- Veil, S.R. (2011). Mindful learning in crisis management. The Journal of Business Communication (1973), 48(2), 116-147.

- Wang, J. (2008). Developing organizational learning capacity in crisis management.

- Advances in Developing Human Resources, 10(3), 425-445.

- Wang, J., & Ritchie, B.W. (2010). A theoretical model for strategic crisis planning: factors influencing crisis planning in the hotel industry. International Journal of Tourism Policy, 3(4), 297-317.

- Wang, J., & Ritchie, B.W. (2013). Attitudes and perceptions of crisis planning among accommodation managers: Results from an Australian study. Safety Science, 52, 81-91.

- Wang, W.T., & Belardo, S. (2005). Strategic integration: A knowledge management approach to crisis management.Paper presented at the System Sciences, 2005. HICSS'05. Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on.

- Wang, Y.S. (2009). The impact of crisis events and macroeconomic activity on Taiwan's international inbound tourism demand. Tourism Management, 30(1), 75-82.

- Yang, J.T. (2008). Effect of newcomer socialisation on organisational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover intention in the hotel industry. The Service Industries Journal, 28(4), 429-443.

- Yin, R.K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (applied social research methods). London and Singapore: Sage.