Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 5

Entrepreneurial Resilience: The Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Entrepreneurial Passion in Disaster Prone Areas

Emrizal, Politeknik Negeri Padang

Werry Darta Taifur, Andalas University

Hafiz Rahman, Andalas University

Endrizal Ridwan, Andalas University

Dodi Devianto, Andalas University

Abstract

Research on entrepreneurial resilience has been growing recently but there has been no study on this topic that performs quantitative measurement to identify the influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion upon entrepreneurial resilience. This paper aims at examining the influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and passion on entrepreneurial resilience in culinary Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) in disaster prone areas. This study used the quantitative method of analysis by applying Structural Equation Modelling with 382 samples of culinary SMEs in disaster prone areas in West Sumatera, Indonesia. This research found that there was no significant correlation between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial resilience while positive and significant correlation was found between entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial resilience. The results can contribute to the development of entrepreneurial resilience theory and be useful for the local government in making policies related to support SME in such disaster prone areas.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Resilience, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, Entrepreneurial Passion, Structural Equation Modeling.

Introduction

An entrepreneur is always faced with various problems in keeping his/her business. Sometimes, those problems appear unexpectedly and may cause serious implications upon their business continuity. Thus, an entrepreneur must possess resilience when overcoming potential circumstances that may disturb their enterprise’s survival.

Resilience is defined as the ability to adapt to rapid and unwanted change of environment as well as the capacity to overcome difficulties and bounce back from traumatic experience (Bonanno, 2012; Zautra et al., 2010). Entrepreneurial resilience is entrepreneurs’ ability to adapt to changes in their business environment and rebound after experiencing adverse situations (Bullough, Renko & Myatt, 2014). An entrepreneur’s resilience becomes the primary factor that underlies his/her success (Markman & Baron, 2003). Therefore, a resilient entrepreneur shall attain higher degree of success instead of the less resilient ones (Hayward et al., 2010). Additionally, entrepreneur community have a higher level of resilience as compared to non-entrepreneur communities, which indicates that such resilience can be used to predict an entrepreneur’s success (Fisher et al., 2016). Consequently, it is important for an entrepreneur to become resilient in order to get success in their business and to maintain business continuity especially in the disaster prone environment.

Measuring entrepreneurial resilience is an important step to be done to ensure entrepreneurial continuity especially in the risky regions (Bullough et al, 2014). Business risks and uncertainties in disaster prone areas are much higher than those in non-disaster prone regions. Therefore, investigations on entrepreneurial resilience in disaster prone areas are considered to be essential in that they can reveal influential factors that trigger and enhance the entrepreneurs’ resilience and survival.

Self-efficacy is one of the reported factors that determine an entrepreneur’s resilience (Lee and Wang, 2017). Self-efficacy guides an entrepreneur to believe in him/herself so that they become confident in making decisions and unafraid of facing risks of failure, expect positive results, and attain business growth (Holienka et al., 2016). Therefore, examining the effect of self-efficacy on entrepreneurs’ resilience becomes crucial especially in the context of culinary SME in disaster prone areas.

In the meantime, entrepreneurial passion constitutes the main component of entrepreneurial process, which contributes to the entrepreneur’s behaviour and performance (Clarysse & Van Boxstael, 2015; Murnieks et al., 2014). Passion is highly crucial in entrepreneurial context, considering that entrepreneurs must deal with challenges from the early phase of their business (Gielnik et al., 2015). Passion is defined as a strong tendency toward activities that one likes or considers important, and in which they invest their time and energy (Vallerand, 2015). Then, entrepreneurial passion refers to the intense positive feeling that is consciously accessible, experienced because of involvement in the entrepreneurial activities, associated with meaningful roles, noticeable in the entrepreneur’s identity, drives the daily entrepreneurial efforts, and persistent in overcoming adversities (Cardon et al., 2009).

Passion constitutes enthusiasm for every activity related to endeavor or business (Cardon et al., 2009). People who are enthusiastic and take seriously a business that they are running will certainly deploy their all potentials for the success of the business. Accordingly, an entrepreneur who has passion for his business at hand will dedicate his/her time and energy to make it work successfully. Therefore, investigation on the relationship between entrepreneurial passion and resilience in entrepreneurs, which has never been conducted especially in disaster prone area, becomes really important.

Considering the important role of entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial self-efficacy, this study examines the correlational factor between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion upon entrepreneurial resilience among culinary SMEs in disaster prone areas in West Sumatera, Indonesia. This research was situated in West Sumatera because native community, i.e. Minangkabau people, in this province have been recognized for their entrepreneurial way of lives. Minangkabau society holds cultural and familial system that contributes directly or indirectly to establishment of such entrepreneurial culture (Rahman, Oktavia & Besra, 2019). Additionally, West Sumatera is one of the disaster prone areas in Indonesia because it is located in the cross section between Eurasian and Indo-Australian plates. Indo-Australian plate dives under the Eurasian plate. This subduction creates ongoing tectonic movement and result in earthquake and tsunami threats (Edwiza & Novita, 2008).

Even though some studies on entrepreneurial resilience have been previously conducted, studies that quantitatively examine the influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion variables have never been done. Thus, this study will contribute to the development of theory of entrepreneurial resilience and its influencing factors.

Literature Review

Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is defined as confidence people have in their ability to produce predetermined level of performance that affect activities in their lives. People with high level of confidence will have high degree of achievement and in many ways will achieve high degree of welfare. Besides, they will gain the ability to overcome difficult tasks and see them as challenges that must be conquered rather than threats that must be eluded (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara and Pastorelli, 2001). Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy (ESE) comprises confidence an individual has on her/his ability to perform task and play the role dedicated toward business success (Chen et al., 1998).

Another definition of self-efficacy dictates that it is a confidence in one’s ability to gather and implement necessary resources, skills, and competence to achieve certain levels of performance (Barone et al., 2004). To conclude, self-efficacy is a motivation that someone has which is implemented through interaction with the environment and the ability or skill in managing resources in order to achieve optimum goal.

In empirical research literature, self-efficacy was proven to have positive impact on organizational performance (Bandura, 2006; Miao et al., 2016). Other studies also support this finding by showing that entrepreneurial self-efficacy moderates the relationship between proactive personality and business growth (Prabhu et al., 2012). Nonetheless, some other studies presented different results where self-efficacy was found to hold negative correlation with individual performance (Tzur et al., 2016; Stajkovic & Lee, 2001). Based on these findings, a quantitative examination on the influence of entrepreneurial self-efficacy upon entrepreneurial resilience is urgently needed.

Entrepreneurial Passion

Vallerand, (2015) defined passion as a strong tendency toward an activity that one likes and considers important, and in which they invest time and energy. Moreover, Vallerand et al. argued that the activity that one prefers will be internalised in his/her identity as far as it is meaningful for him/her. Cardon & Kirk (2013) also suggested that entrepreneurial passion is the love to the business itself while Vallerand et al. (2015). Defined it as a strong tendency toward the activity that one likes and considers important. Entrepreneurial passion will direct an entrepreneur to invest higher level of energy and effort for their business success (Balgiasvhili, 2017).

A recent study (Schutte & Mberi, 2020) shows that one’s entrepreneurial resilience can be influenced by two factors. Firstly, it can be characterized by internal factors that constitute entrepreneurial passion, personal traits, support system, vision, system of faith, and network. The second factor includes employee, financial resources, and business structure.

Entrepreneurial Resilience

Entrepreneurial resilience constitutes a dynamic and developing process from which an entrepreneur acquires knowledge, ability, and skills to assist them in facing uncertain future with positivity, creativity, and optimism by relying on their own resources (Ayala & Manzano, 2014).

Bonanno (2012) defined resilience as the ability to maintain psychological and physical stabilities from anything that may disturb activities. Lee and Wang (2017) proposed another definition that prescribes resilience as the ability to overcome traumatic events and bounce back from despair or the success in overcoming challenges and regaining positive result despite adverse circumstances. An entrepreneur who has resilience can rebound from failure and survive through difficult times (Hayward et al., 2010). A resilient enterprise and individual will be ready in dealing with disturbances thereby being able to estimate their entrepreneurial success (Ayala & Manzano, 2014).

Dimensions of hardiness, resourcefulness, and optimism have positive and significant correlation with business growth and success (Ayala & Manzano, 2014). Entrepreneurial resilience that is originated from hardiness and persistence can also predict entrepreneurial success (Fisher et al.,2016).

Results from previous studies indicate that it is important for an entrepreneur to have resilience so that his/her business can achieve success and adversities can be overcome. This trait becomes even more necessary for SMEs located in disaster prone areas where threats can come at any time and risks are much higher. Given that there has been no research that quantitatively examines the effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion on entrepreneurial resilience, this study becomes essential for the development of entrepreneurial resilience theory.

Hypotheses

The authors suggest that there is a relationship between entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial resilience:

H1: Entrepreneurial self-efficacy is positively and significantly related to entrepreneurial resilience

H2: Entrepreneurial passion is positively and significantly related to entrepreneurial resilience

Methodology

Population

Data population consist of culinary Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in disaster prone areas in West Sumatera, which were distributed throughout six cites / municipalities that are marked to have higher disaster potentials as compared to all other cities / municipalities in West Sumatera. Culinary SME was chosen as the research object because food sector becomes the leading sector among five top industries in Indonesia, which comprise textile and garment, food and drink, chemicals, automotive, and electronics.

Samples

From the total population of 51,130 units of culinary SME across six targeted cities / municipalities, 382 samples were taken (Krejcie dan Morgan, 1970) by means of probability sampling technique using multistage cluster sampling procedure.

Methods of Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed by using Structural Equation Modelling, which basically consists of Measurement Model and Structural Model. Measurement Model describes the correlation between latent and manifest variables while Structural Model reveals correlation among latent variables or between exogenous and endogenous variables.

Results

Test of Goodness of Fit

Before Structural Model test was conducted, Measurement Model, which consists of Goodness of Fit, validity, and reliability tests were carried out firstly. Result of test of Goodness of Fit shows that all test criteria were good fit. Chi square value of 0.129 had met the criteria of ≥ 0.05. Goodness of fit index scored 0.979, which also met the cut-off range score between 0-1. Adjusted goodness of fit index was 0.960 of the required range score 0-1. The closer the score to 1, the better the result is. Root Mean Square Error of Approximation scored 0.026, which was ≤ 0.08. Root Mean Residual scored 0.006 which was ≤ 0.05. Normed Fit Index scored 0.976 and met the required score range of 0-1. Tucker Lewis Index scored 0.992 which was also within the score range of 0-1. Overall, test of goodness of fit indicated that the model was fit thereby the next process can be carried out.

Validity Test

A test of construct validity was performed to examine whether construct indicators can explain the construct itself. The result of the test showed that all indicators were valid as all indicators produced t value or CR above 1.96 and p-value of 0.05.

In addition, loading factors can also be examined in order to prove whether an indicator was the true part of the construct. Table 1 presents the output of SEM AMOS and provides much clearer illustrations.

| Table 1 Loading Factor Scores | |

| Variables | Estimate |

| ESE 1 ˂--- ESE | 0.719 |

| ESE 2 ˂--- ESE | 0.800 |

| ESE 3 ˂--- ESE | 0.752 |

| ESE 4 ˂--- ESE | 0.768 |

| ESE 5 ˂--- ESE | 0.682 |

| ESE 6 ˂--- ESE | 0.658 |

| EP 1 ˂--- EP | 0.683 |

| EP 2 ˂--- EP | 0.732 |

| EP 3 ˂--- EP | 0.698 |

| Y 3 ˂--- ER | 0.722 |

| Y 2 ˂--- ER | 0.786 |

| Y 1 ˂--- ER | 0.751 |

The estimation column indicates loading factors for every indicator against latent variable or related construct. Generally, loading factor scores that are above 0.5 indicates that they are parts of their construct (Hair et al., (2014)). Loading factor column in the table shows score above 0.5. This means that all indicators can explain their existing construct.

Test of Reliability

Reliability test intends to identify the extent to which the testing tool can provide similar score if the measurement is repeated on the same subject (Hair et al.2014). A construct can be considered reliable if it’s Construct Reliability (CR) score is ≥ 0.7. In this study, there were three constructs that were tested, namely constructs for entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial passion, and entrepreneurial resilience, as depicted in Table 2.

In Table 2, Construct Reliability scores for entrepreneurial sel-efficacy, entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial resilience exceeded the cut-off score ≥ 0.7. Consequently, all constructs and latent variables were proven to be reliable as the testing instrument.

| Table 2 Test of Construct Reliability | ||

| Constructs | Construct Reliability | Remarks |

| Entrepreneurial Sel-Efficacy | 0.959 | Reliable |

| Entrepreneurial Passion | 0.912 | Reliable |

| Entrepreneurial Resilience | 0.949 | Reliable |

Test of Structural Model

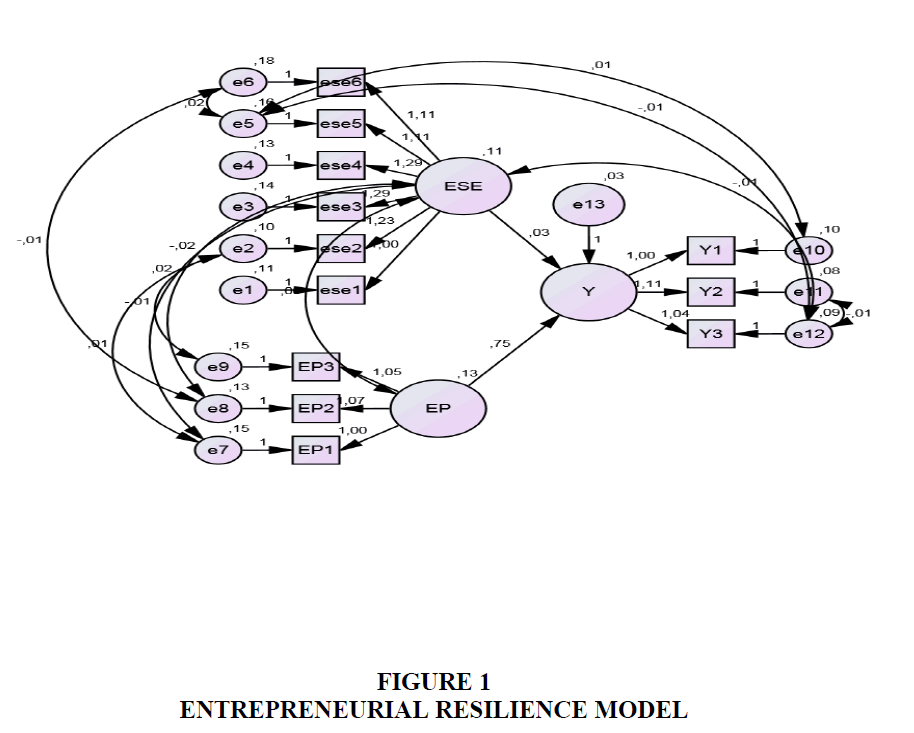

Structural Model has the same component as the testing model. However, all constructs in the testing model become exogenous variables while there is a cause-and-effect relation among variables in the structural model where there are independent and dependent variables as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 illustrates the structural model that consists of two exogenous variables (entrepreneurial sel-efficacy and entrepreneurial passion) and one endogenous variable (entrepreneurial resilience). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy variables has six indicators while entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial resilience variables have three indicators respectively. This model shows a causal relation between exogenous and endogenous variables, as depicted in Table 3.

| Table 3 Test of Structural Model | ||||

| Direction of Influence | Estimate | CR | P-Value | Remarks |

| Entrepreneurial Sefl-Efficacy → Entrepreneurial Resilience | 0.026 | 0.325 | 0745 | Not significant |

| Entrepreneurial Passion → Entrepreneurial Resilience | 0.753 | 8.770 | *** | Positive and significant |

Table 3 shows that Critical Ration (CR) score was 0.325 from the required >1.96 and p-value was 0.754 from the cut-off score < 0.05. This concludes that there was no significant correlation between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial resilience. Accordingly, entrepreneurial self-efficacy did not influence an entrepreneur’s entrepreneurial resilience.

Test of structural model on entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial resilience variables resulted in the p-value 0.000 and CR score 8.770. The result confirms that correlation between these two variables was significant and real. Estimate score of correlation between the two variables was positive, i.e. 0.753, which indicates that an entrepreneur who has higher level of entrepreneurial passion tends to have higher level of entrepreneurial resilience as well.

Discussion

Despite numerous studies reporting that self-efficacy contributes to success and business growth, there are a few studies that proved negative contribution of self-efficacy (Tzur et al., 2016; Stajkovic and Lee, 2001). These researches proved no real or significant correlation between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial resilience. Thus, high or low degree of an entrepreneur’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy is not correlated nor has influenced his/her resilience. The high p-value of 0.745 and the low CR score of 0.360 became strong evidence for this argument.

Such non-significant correlation between self-efficacy and entrepreneurial resilience was seemingly caused by the lack of SME entrepreneurs’ ability at many aspects such as in developing new ideas and product, building innovative working environment, initiating new relations with investors, overcoming unexpected adversities, and developing human resources.

Likewise, culinary SME entrepreneurs in West Sumatera do not seem to have acquired the necessary abilities to develop their product. Innovation and services for their product remain static over time in that they rarely launch new products or make innovation from their existing product in order to surprise customers. Food menu from one restaurant to another is almost the same. Their culinary business does not have specificity that distinguishes their products and services from other competitors. Culinary enterprise specialised in long lasting food products also suffer from unattractive and unpractical packaging to be taken away by visitors for their friends and family.

Respondents in this research did not seemingly have the ability to foresee business opportunities in order to grow and develop their business in the future. They were not capable of predicting their business development in the future and creating new products that will meet potential customers’ future needs.

In terms of establishing innovative working environment, SME entrepreneurs in West Sumatera did not seem to provide much chance to encourage their employees to think of new, creative, and innovative ideas. Work pattern tends to be consistently monotonous from time to time. There has been no particular time and space especially dedicated to discuss and bring up new ideas and thoughts including evaluating their current business operation.

SME entrepreneurs in this disaster prone area still tended to manage their business in usual and conventional manners. They did not seem to have dreams for bigger businesses. As a consequence, initiatives to establish new relation with investors for developing their business were never realised. They still relied on their own or their family’s financial resources so that it had never crossed their minds to expand their business by building partnership with outsiders who have bigger financial resources.

Moreover, the respondents admitted to have no clear vision yet, no collectively decided goals to be achieved, and no long term planning whatsoever. They did not seem to have carefully planned moves in order to deal with business challenges or to anticipate troubles from unexpected circumstances. Reactive management was still coming into play when facing unwanted situations with no contingency plan. There was no capability in developing the existing resources in order to improve their employee’s capacity and competences. Skills were acquired naturally through self-learning methods so that it really depends on the personnel of the enterprise whether to acquire necessary skills or not.

Meanwhile, entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial resilience constructs appeared to have positive correlation because the estimate values were positive 0.753. Besides, both constructs had significant correlation with p-value 0.000 and CR score 8.770. This means that an entrepreneur with high entrepreneurial passion will also have high entrepreneurial resilience.

On the other hand, entrepreneurs of culinary SMEs in disaster prone areas of West Sumatera were keen to continuously observe their environment in order to recognize business opportunities. They felt more enthusiastic with the business because they ran their own enterprise so that they have strong motivation in developing it. These culinary entrepreneurs’ senses of excitement and enthusiasm were partly caused by the fact that this type of business is also their hobby. Therefore, they felt really enthusiastic and happy in running it, which contributes to their resilience when dealing with adversities and which helps them to bounce back quickly after experiencing failure.

In this respect, Baum and Locke (2004) suggested that there is positive correlation between passion and entrepreneurial commitment that pushes individuals to acquire useful skill in order to manage his/her business. Passion will force entrepreneurs to improve competences, skills, and innovative knowledge (Murnieks et al., 2014).

Conclusion

To conclude, testing results on the structural equation shows that there was no significant correlation between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial resilience variables. This may be due to the fact that culinary SME entrepreneurs did not yet have sufficient capacity in designing new service products. They were unable to build innovative working environment and did not have the initiatives to establish network with outside investors. Moreover, these culinary entrepreneurs were not able to define their company’s goals and had lacked of contingency plans in anticipating and overcoming unexpected challenges. Last but not least, such non-significant correlation may also be caused by their inability to develop their human resources in the enterprise.

On the other side, this research proved significant correlation between entrepreneurial passion and entrepreneurial resilience constructs. They both also acquired positive values which indicate that an entrepreneur with high entrepreneurial passion tends to have high entrepreneurial resilience as well. Culinary SME entrepreneurs appeared to have passion in establishing their companies, be keen observers to their environment in order to recognize business opportunities, and retain their passion in developing the enterprise they were managing.

Thus, findings of this research can contribute to the development of theories on entrepreneurial resilience especially in the parts associated with factors that influence the resilience. Results of this study may also be useful for the government in that the entrepreneurs’ psychological aspects that are related to resilience need addressing in the event of overcoming disasters. Therefore, the affected entrepreneurs can bounce back from their sufferings due to the catastrophe and redevelop their business successfully.

References

- Ayala, J.C., & Manzano, G. (2014). The resilience of the entrepreneur. Influence on the success of the business. A longitudinal analysis. Journal Of Economic Psychology , 42, 126–135.

- Balgiasvhili. (2017). Comparing entrepreneurial passion of social and comercial entrepreneurs in the Czech Republic. Central European Business Review, 6(4), 45-61.

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In M.F. Pajares &. T. Urdan (Eds.), Self- efficacy beliefs of adolescents (5, 307-337). Greenwich, CT: Information Age.

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G., & Pastorelli, C.(2001).Self‐efficacy beliefs as shapers of children's aspirations and career trajectories. Child development, 72(1), 187-206.

- Baron, R.A, Mueller, B.A, & Wolf, M.T, (2016). Self-Efficacy and entrepreneur’s adoption of unattainble goals: The restraining effect of self control. Journal of Business Venturing. 31, 55-71.

- Baum, J.B., & Locke (2004). Relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill and motivation to subsequent venture and growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4) 587-598.

- Bonanno,G.A. (2012) Uses and abuses of the resilience construct: Loss, trauma, and health-related adversities. Social Science and Medicine, 74(5), 753–756.

- Boyer, D.A., Zollo, J.S., Thompson, C.M., Vancouver, J.B., Shewring, K., & Sims, E. (2000). A quantitative review of the effects of manipulated self-efficacy on performance. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Society, Miami, FL.

- Bullough, A., Renko, M., & Myatt, T. (2014) Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 473–499.

- Cardon, M.S., Sudek, R., & Mitteness, C. (2009). The impact of perceived entrepreneurial passion on angel investing. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 29(2).

- Cardon, M.S., & Kirk, C.P. (2013). Entrepreneurial passion as mediator self-efficacy to persistence relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice .

- Carver, C.S., Sutton, S.K., & Scheier, M.K. (2000). Action, emotion and personality: Emerging conceptual integration. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 741-751.

- Cervone, D., & Wood, R. (1995). Goals, feedback and the differential influence of self regulatory processes on cognitively complex performance. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19(5), 519-545.

- Chen, C., Greene, P., & Crick, A. (1998). Does emtrepreneural self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers ? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 295-316

- Clarysse, B., & Van Boxstael, A., (2015). A tale of two passions: a passion for the “profession” and a passion to “develop the venture”. In: Academy of management Proceedings. Academy of Management.

- De Clercq, D., Honig, B., & Martin, B. (2012). The roles of learning orientation and passion for work in the formation of entrepreneurial intention. International Small Business Journal, 31(6), 652–766.

- Dranovsek, M., Cardon, M., & Patel, P.C. (2016). Direct and Indirect Effects of Passion on Growing Technology Ventures. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal , 10, 194-213

- Edwiza, D., & Novita, S. (2008).Pemetaan percepatan tanah maksimum dan intensitas seismik kota padang panjang menggunakan metode kanai. Jurnal Geofisika, 2(29).

- Fisher, R., Merlot, E., Johnson, L.W. (2018). The obsessive and harmonious nature of entrepreneurial passion. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(1), 22-40,

- Foo, M.D., Uy, M.A., & Baron, R.A. (2009). How do feelings influence effort? An empirical study of entrepreneurs’ affect and venture effort. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 1086–1094.

- Gielnik, M.M., Spitzmuller, M., Schmitt, A., Klemann, D.K., & Frese, M. (2015). I put in effort, therefore I am passionate: investigating the path from effort to passion inentrepreneurship. Acad. Manag. J. 58 (4), 1012–1031.

- Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Abin,B.J., & Anderson, R.E. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis. Pearson Education Limited (1)

- Hayward, M.L.A., Forster, W.R., Sarasvathy, S.D., & Fredrickson, B.L. (2010). Beyond hubris: How highly confident entrepreneurs rebound to venture again. Journal of Business Venturing , 25(6), 569–578.

- Ho, V.T., & Pollack, J.M., (2014). Passion Isn't always a good thing: examining entrepreneurs’ network centrality and financial performance with a dualistic model of passion. Journal of Management Studies, 5 1(3), 433–459.

- Holienka, M., Jancovicova, Z., & Kovacicova, Z. (2016). Driver Women Entrepreneurship in Visegrad Countries : GEM Evidence. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences, (220), 124- 133.

- Lee. J., & Wang. J. (2017). Developing Entrepreneurial Resilience: Implications for Human Resource Development. European Journal of Training and Development. 41(6), 519-539

- Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G.R., & Lester, P.B. (2006). Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Human Resource Development Review , 5(1), 25–44.

- Luthar, S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562

- Ma. C., Gu. J., & Liu.H. (2017). Entrepreneurs’ passion and new venture performance in China, International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal.

- Markman, G.D., & Baron, R.A. (2003). Person-entrepreneurship fit: Why are some people more successful as entrerpreneur than others. Human Resources Management Review, (13), 281-301.

- Miao, C.Q., & Ma, D. (2016). The Relationship between Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Firm Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Main Moderator Effect. Journal of Small Business Management

- Murnieks, C.Y., Mosakowski, E., & Cardon, M.S. (2014). Pathways of passion identity centrality, passion, and behavior among entrepreneurs. Journal of Management, 40(6), 1583–1606.

- Prabhu, V., McGuire, S., Drost, E., & Kwong, K. (2012). Proactive personality and entrepreneurial intent: Is entrepreneurial self-efficacy a mediator or moderator? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 18(5), 559-586

- Rahman, H., Oktavia, S., & Besra, E., (2019). Psycho-Cultural Perspective on the Formaton of Entrepreneurial Culture of Minangkabau Tribe West Sumatera Indonesia. Udayana Journal of Culture and Law, 03(1), 53-77.

- Schutte, F., & Mberi, F. (2020). Resilience As Survival Trait for Start-Up Entrepreneurs. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 26(1), 1-15.

- Stajkovic, A.D., & Lee, D.S. (2001). A meta-analysis of the relationship between collective efficacy and group performance. Paper presented at the national Academy of Management meeting, Washington, DC.

- Syed, I., & Mueller, B. (2015). From passion to alertness: An investigation of the mechanisms through which passion drives alertness. Academy of Management Proceedings, (1), 15608.

- Tzur, K.S., Ganzach, Y., & Pazy. (2016). On the positive and negative effects of self-efficacy on performance: Reward as a moderator, Human Performanc e, 29(5) 362-377.

- Vallerand, R.J. (2015). The Psychology of Passion: A Dualistic Model, Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- Zautra, A.J., Hall, J.S., & Murray, K.E. (2010). Resilience: A new definition of health for people and communities. In J.W. Reich, A.J. Zautra, & J.S. Hall (Eds).