Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

Entrepreneurship in the Shadow Economy: The Case Study of Russia and Ukraine

Irina A Markina, Poltava State Agrarian Academy

Antonina V Sharkova, Financial University

Martha Y Barna, Lviv University of Trade and Economics

Abstract

The shadow economy exists in all countries of the world. Its forms and structure have a regional dimension. Analysis of the shadow economy shows key features, which are common to all countries in a particular economic region. The average index of the shadow economy is 18% for OECD countries, and for the transition economies, this index is about 37%, which confirms the concept of regionalization of economic. Shadow economy depends not only on economic but also on socio political factors. The combination of these factors creates the motivation of the participants of the shadow economy. The burden of direct and indirect taxes high density of regulations and level of corruption are considered to be the main factors, which lead to high indicators of shadow economy in transition economies. Based on these results, the most outstanding problems that have the greatest impact on entrepreneurs were distinguished for each country.

Keywords

Corruption, Economy, Entrepreneurship, Public Institutions, Shadow Economy, Tax Burden.

JEL Classification

H100, O170.

Introduction

All economies of the world have a shadow sector (Schneider et al., 2010). It differs mainly in the structure and GDP. The shadow economy indicators have a distinct regional allocation. The average index of the shadow economy is 18% for developed countries (OECD), and for the transition economies, this index is about 37% (Buehn and Schneider, 2012). The high level of the shadow economy leads to inefficient use of limited resources, inefficient technologies. It withdraws investment funds and enhances inequality of incomes. Such macroeconomic indicators of the country and the whole region as household income, supply and demand, labour power and employment cease to be true. As a result, economic and social policies, based on these data will be ineffective (Blackburn et al., 2012; Capasso and Jappelli, 2013).

At the same time, the shadow economy formalization could provide fiscal revenue growth by 10-20% within several years in developing and transition economies. A policy of modernization and qualitative reforms may be the basis for such a process, as long as coercive methods in combating the shadow economy often lead to the opposite effect (Bergman and Nevarez, 2006; Murphy, 2005).

The main component of the shadow economy in transition economies is “hidden enterprise culture” or shadow (informal) entrepreneurship (Dickerson, 2011; Williams and Nadin, 2010; Ilahiane and Sherry, 2008; Williams and Windebank, 2006).

The shadow economy is characterized by uncontrolled production of low-quality goods, production and sale of prohibited goods, non-payment of taxes and fees, illegal and unprotected occupation, crimes associated with the shadow economy (fraud, bribery, extortion, etc.). High level of shadow economic activity has a negative impact on the image of the country, its competitiveness, and international economic interactions and on the efficiency of structural and institutional reforms.

At the same time, not full payments to the state budget contribute to social security regression and hinder the development of other sectors. Besides, shadow economic activity distorts the mechanisms of competition between the economic entities.

At the same time, there are no effective measures to prevent and combat the shadow economic activity, but there are auxiliary factors of its development. These factors involve bureaucracy on the part of officials, high level of unemployment and poverty among the population, high taxation and strong corrupt practice among state bodies, conflict and imperfection of legislation.

Appropriate measures are necessary to take in order to minimize the shadow economy, to remove factors contributing to shadow activity and to stimulate legitimate economic activity. This, in turn, will lead to economy development with healthy market activity. These aspects have grounded this study.

The Shadow Economy Definition And Measurement

Considering that the concept of shadow economy (informal, black, underground economy) is wide enough, it is necessary to clearly define what it means. We follow the definition provided by Friedrich Schneider as legal business activities that performed outside the reach of government authorities and deliberately concealed from them (Schneider and Schneider, 2004). This definition of shadow economy includes only legal activities, so illegal economy (drug dealing, smuggling, prostitution, fraud etc.) as well as household and self-made activities are not included.

A major problem in studying the shadow economy is the determination of its measurement, inasmuch as the members of the shadow economy carry on illegal business and do not want to be exposed. There is an on-going debate on the most appropriate method of research among the researchers of shadow economy (Bhattacharyya, 1999; Feld and Larsen, 2005; Feld and Schneider, 2010; Schneider, 2005). Three most common methods are distinguished: direct measurement at the micro level, aimed at determining the size of the shadow economy in a certain period of time (e.g. survey method); indirect measurement that uses macroeconomic indicators and their differences to study shadow economy over a period of time (e.g. currency amount approach); statistical models that use statistical instruments to measure the shadow economy (Kirchgässner, 2016).

Currently, the most widely used method of measuring the shadow economy is Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes (MIMIC) procedure. This approach takes into account not one indicator or one-dimensional factors, but both the numerous reasons for shadow economy development and its multiple effects over time. It takes into account the multiple causes and multiple indicators of the phenomenon to be measured. The currency demand method is also popular. It was used to estimate the level of shadow economy of most countries (Schneider, 2005). Under this method, the average index of the shadow economy in Ukraine from 1999 to 2015 is 44.6%, while there is an upward trend from historic low in 2013 (39.5%) to the current rate (44.6%). The average index in Russia is 39.7%, and there is a stable rete of 41% in the last 5 years (Conditions 2016). In the period from 2007 to 2014, the level of shadow economy in Ukraine was lower than in Russia. When using this method, a miscalculation can be up to 10- 15% (Schneider, 2016).

The main problems of measuring the shadow economy involve all of the abovementioned methods that provide only an approximate quantitative meaning and development trends; shadow economy structure and forms that is difficult to determine; reasons for shadow economy development that dependent on people’s motivation to work in the informal sector.

The structure and forms of shadow entrepreneurship differ depending on the geographic and economic region. There are two possible variants for entrepreneurs to work in the informal sector-when companies conduct only a part of their operations in the shadow economy, while others do not participate in the formal economy at all. A situation when large firms are represented in the informal sector and hide some of their income is peculiar to the developed countries. In developing countries, even large companies prefer to conduct all of their operations in the shadow economy (Williams and Nadin, 2010). However, this regularity is also observed for the economic regions with different levels of income within a country (Williams, 2009b).

In the context of studying the motivation of entrepreneurs, in the literature there is a division of entrepreneurs into necessity-driven and opportunity-driven entrepreneurs (Smallbone and Welter, 2004; Aidis et al., 2007; Maritz, 2004). Economic zoning is also peculiar for this indicator. Thus, the amount of opportunity-driven entrepreneurs is larger in economically developed countries and regions.

Among the countries of Eastern Europe Ukraine has the biggest number of entrepreneurs who operate in the shadow economy. According to recent studies, only 10% of entrepreneurs work fully in the formal sector, 36% hide part of their operations and incomings, and about 51% work exceptionally in the informal sector. Russia is characterized by a higher degree of regionalization. In Moscow, the number of entrepreneurs who are fully or partially participate in the shadow economy tends to 100% (Williams, 2009a).

These indicators represent that any indirect methods of measuring the shadow economy would give only approximate values. Direct methods of evaluation are costly and not exact due to the nature of the shadow economy-its subjects do not want to be exposed and discovered (Schneider, 1994). Signs of a crisis led to a growth of informal sector, and the crisis may not be only economic. Political and social signs of a crisis have the same effect (Schneider, 2010b).

Most studies of the causes and growth of the shadow economy consider, in general, economic indicators (Friedman et al., 2000; Blackburn et al., 2012; Bajada and Schneider, 2005). At the same time, the socio political environment has the same influence on the decision of entrepreneurs to work in the informal sector (Elbahnasawy et al., 2016).

In order to achieve these results, it is necessary to conduct a complex of economic, social and political actions aimed at bringing out the economy out of the shadows. The effectiveness of any policy depends on how its creators understand things that are needed to be complete. The purpose of such a policy is possible to determine only through the analysis of the causes that contribute to the development of the shadow entrepreneurship.

Thus, for the development of effective public policy aimed at formalization of the shadow entrepreneurship, two factors are needed to know: the reasons, which make the entrepreneur to prefer the shadow economy to formal; the motivation of the entrepreneur to work in the informal sector. The main factors affecting the indicators of the shadow economy are following: tax burden and tax morale (Torgler and Schneider, 2009; Torgler et al., 2010); quality of public institutions (Dreher et al., 2009; Schneider, 2010a); level of regulations.

Basic relations and the impact of these factors on the shadow economy is quite simple to calculate-the higher tax morale and the tighter the level of regulations are, the bigger the shadow economy is. The higher tax morale and quality of public institutions, the smaller the shadow economy is.

However, traditional methods of measuring the shadow economy are not able to determine the extent to which each of these reasons affect the decision of entrepreneur to work in the shadow economy. The simplest way is survey method. However, this method is extremely costly; in addition, the sample of people is often limited. There is no guarantee to get a truthful answer conducting a survey by public services there, as representatives of the informal sector do not want to be discovered.

International economic indices are used to obtain reliable information from an independent source about macroeconomic indicators of the country. The article presents a comparative analysis of the international economic indices in Russia and Ukraine. We suppose that international indices can be used to identify problem areas.

The purpose of the study is to develop a mechanism for minimizing the shadow economy in entrepreneurship by introducing a formalization policy.

Methodology

In order to get the most objective assessment of the macroeconomic characteristics of countries, the independent international indicators and results of international research on the shadow economy were used.

To evaluate the key economic and socio-political processes, such global indicators were analyzed: World Bank’s Doing Business 2016 (Bank, 2016), World Bank`s the Worldwide Governance Indicators (Bank, 2014), Corruption Perceptions Index 2015 by Transparency International (International, 2015), The Global Competitiveness Index 2016 (Schwab, 2106), Freedom in the World 2016 by Freedom House (House, 2016), as well as calculations of Friedrich Schneider and his co-authors (Conditions, 2016).

Each of these indices contains several indicators, but this study emphasizes those that reflect the motivation of entrepreneurs to work in the informal sector, or directly affects it (Table 1).

| Table 1 INTERNATIONAL INDEXES IN THE WORLD |

|

| Index | Studied sub-indices |

| World Bank’s Doing Business 2016 | Starting a business |

| Dealing with construction permits | |

| Paying taxes | |

| Enforcing contracts | |

| Resolving insolvency | |

| Registering Property | |

| World Bank`s the Worldwide Governance Indicators | All the indicators, namely |

| Voice and Accountability | |

| Political Stability and Absence of Violence | |

| Government Effectiveness | |

| Regulatory Quality | |

| Rule of Law | |

| Control of Corruption | |

| Global Competitiveness Index | Sub Index A: Basic requirements |

Note: Corruption Perceptions Index and Freedom in the World do not have sub-Indexes.

Publications of the period of 1995-2016 were analysed in order to identify the impact of the shadow economy on social and economic processes, the reasons that led to the growth of the shadow economy, the characteristics of the shadow economy in transition economies, and methods of “unshadowing” the economy.

Results

Reflection of the causes of the shadow economy in the economic indices

Russia and Ukraine have two biggest transition economies with different forms and structure of the shadow entrepreneurship. Comparative analysis of main indices is presented in Table 2.

| Table 2 INTERNATIONAL INDEXES IN UKRAINE AND RUSSIA |

|||

| Index | Studied sub-indices | Ukraine | Russia |

| Shadow economy | 1 (2012) | 1 (2012) | |

| -1 (2013) | -1 (2013) | ||

| -1 (2014) | -1 (2014) | ||

| World Bank’s Doing Business 2016 | General | 83 | 51 |

| Starting a business; | 30 | 41 | |

| Dealing with construction permits; | 140 | 119 | |

| Paying taxes; | 107 | 47 | |

| Enforcing contracts; | 98 | 5 | |

| Resolving insolvency; | 141 | 51 | |

| Registering Property | 61 | 8 | |

| World Bank’s the Worldwide Governance Indicators | Voice and Accountability; | -0.3 (2012) | -1 (2012) |

| -0.3 (2013) | -1 (2013) | ||

| -0.1 (2014) | -1 (2014) | ||

| Political Stability and Absence of Violence; | -0.1 (2012) | -0.8 (2012) | |

| -0.8 (2013) | -0.7 (2013) | ||

| -1.9 (2014) | -0.8 (2014) | ||

| Government Effectiveness; | -0.6 (2012) | -0.4 (2012) | |

| -0.6 (2013) | -0.4 (2013) | ||

| -0.4 (2014) | -0.1 (2014) | ||

| Regulatory Quality; | -0.6 (2012) | -0.4 (2012) | |

| -0.6 (2013) | -0.4 (2013) | ||

| -0.6 (2014) | -0.4 (2014) | ||

| Rule of Law; | -0.8 (2012) | -0.8 (2012) | |

| -0.8 (2013) | -0.8 (2013) | ||

| -0.8 (2014) | -0.7 (2014) | ||

| Control of Corruption; | -1 (2012) | -1 (2012) | |

| -1.1 (2013) | -1 (2013) | ||

| -1 (2014) | -0.9 (2014) | ||

| Global Competitiveness Index | Institutions | 100 | 130 |

| Infrastructure | 35 | 69 | |

| Macroeconomic environment | 40 | 134 | |

| Health and primary education | 56 | 45 | |

| Corruption Perceptions Index | 130 | 119 | |

| Freedom in the World | Partly Free | Not Free | |

Let us examine the main factors influencing the motivation of entrepreneurs and their reflection in international indices.

Tax Burden

Many researchers point out that tax burden is one of the main causes of the shadow economy existence (Feige, 2007; Buehn and Schneider, 2012; Buehn and Schneider, 2013; Schneider et al., 2010). The number and amount of taxes that should be paid for carrying out a business and the desire of an entrepreneur to cover all or part of the amount of finance from state are directly connected. The features of this process in developed and transition countries should be distinguished. If economic agents in developed countries tend to avoid excessive, in their view, the tax assets by bringing some of their operations into informal sector, the agents in the transition countries do not participate in the formal economy at all. In addition, an important indicator is tax morale-the desire of economic agent to pay taxes, but it is difficult to measure. Tax burden consists of the following key indicators: direct tax burden, indirect tax burden and tax system complexity.

Empirical evidence shows that the most important parameters that determine tax complains are power and trust (Muehlbacher and Kirchler, 2010). One of the key differences of transition countries is bureaucracy, which is reflected in distrust of the state to economic agents and attempt to increase the level of state control. The growth of amount of accounting information, preparation and presentation of which requires more time, is the outcome of such policy. As a result, economic agents lose their confidence in the state, trying to resolve issues quickly through an “appropriate intermediary”, with following transition into the informal sector.

However, even a significant reduction of the tax burden and tax rate as a separate measure would not lead to a significant reduction of the shadow economy (Schneider, 2012).

For example, the main problem in Ukraine is the highest tax rate in the region. It averages 52.2%. In Russia, this figure is 47% and 34.8% for the region as a whole, in Belarus-51.8%, in Georgia-16.4%, in Moldova-40.2%, in Poland-40.3% (Bank, 2016a).

Quality of Public Institutions

Public institutions play a key role in conducting economic policies. Public institutions, which are suffering bureaucracy and corruption, even with democratic and balanced legislation would not be able to ensure the rule of law and would cause the transition into the shadow economy. The most important indicators of public institutions are corruption level and rule of law.

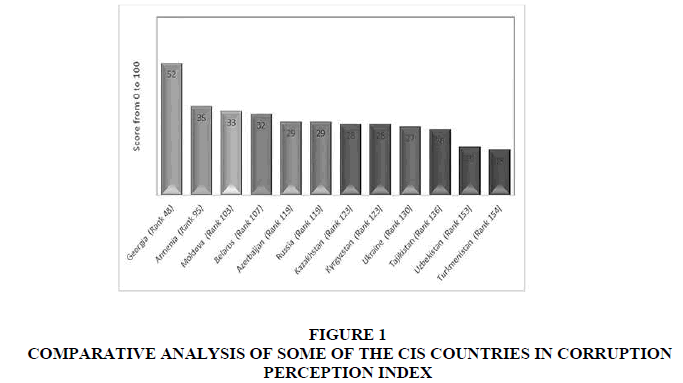

In the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index 2015, Russia and Ukraine are ranked 119th and 130th out of 168 countries in the world. This fact makes Ukraine the most corrupted country in Eastern Europe and one of the most corrupted countries in the world (International, 2015). Comparative results for the region are presented in Figure 1.

Source: Authors' calculations based on the assumptions explicitly stated in the exposition of the model

The level of corruption affects the level of trust to public institutions to the maximum extent. There is an inverse relationship-the higher the level of corruption is, the lower the level of trust is (Clausen et al., 2011). The level of trust is directly related to the level of tax morale and tax compliance. Entrepreneurs do not see any necessity for work in the formal economy and pay taxes if they know that most of these facilities would remain in the pockets of officials.

In addition, according to Index data, the most corrupted sector in Ukraine is a justice system. Entrepreneurs do not feel themselves protected, because even if they go to court, its decision will not always be just.

Level of Regulations

There is a relationship between the shadow economy and the level of regulations–the higher the density of regulation is, the greater total shadow economy is (Friedman et al., 2000; Johnson et al., 1997).

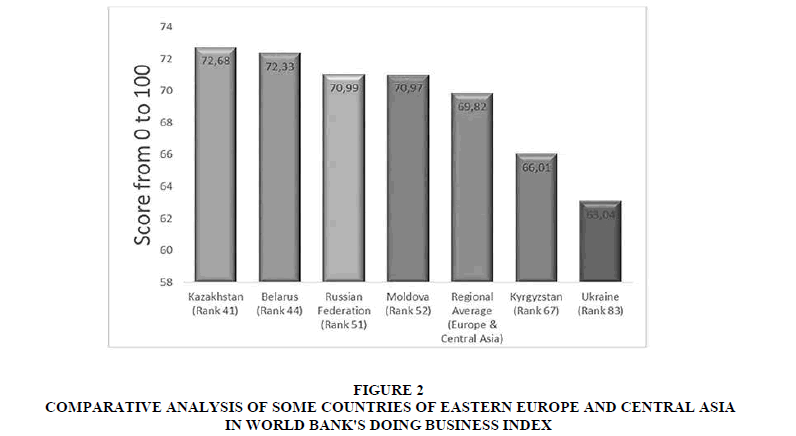

In order to get an independent assessment of the quantity and quality of regulations, it is better to use World Bank's Doing Business Index, as it measures and tracks changes in regulations of 11 key socioeconomic spheres: starting a business, construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting minority investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, resolving insolvency and labour market regulation (Bank, 2016a).

Ukraine is currently ranking 83th place, and it is the lowest position among the countries of the region, while Russia is on 51th position (Figure 2) (Bank, 2016b).

Figure 2: Comparative Analysis Of Some Countries Of Eastern Europe And Central Asia In World Bank's Doing Business Index

Source: authors' calculations based on the assumptions explicitly stated in the exposition of the model

A large number of existing regulations in different spheres is primarily connected with the high level of corruption. The sources of corruption transactions are receiving of a building permission, power supply or dealing with a problem of financial insolvency.

The higher the number of required documents is and the more time and money are needed, the greater the motivation to bribery is. At the same time, it is not profitably for the entrepreneur to pay bribes while working in the formal economy. This is a specific system of double taxation when the entrepreneur pays formal and informal tax, and informal tax means a bribe for one or another permit. In this case, the entrepreneur decides on the shadow economy, where he also pays a “tax” as a bribe for the opportunity to work in the informal sector.

Political Situation and Stability

This factor is practically not considered as a cause of growth of shadow economy. Only recent study of Elbahnasawy (Elbahnasawy et al., 2016) examines the relationship of the political environment and the shadow economy. However, this work considers only the problems of political instability and political polarization.

The situation in the East of Ukraine reflects primarily on the level of public support for government. The government’s failure to end the war, to implement reforms and to stabilize the situation in the country arouse mistrust of its competence and function of protection of citizens’ interests. These conclusions are supported by practical research. A survey conducted in February 2016 by the Gorshenin Institute showed that the level of public support for the authorities is only 22.1% (Gorshenin Institute, 2016). Distrust of the government is another stimulus transition to the shadow economy.

Since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine, more than 1 million people were forced to leave their places of residence and become internal migrants (Coupe and Obrizan, 2016). In new places, most migrants work in the informal sector, as they urgently need a job. Moreover, the emergence of a large number of labour migrants destabilizes the labour market. Majority of the displaced persons are willing to work for lower wages, and it reduces overall wage and increases the level of unemployment. In turn, the shadow labour market allows entrepreneurs to save money.

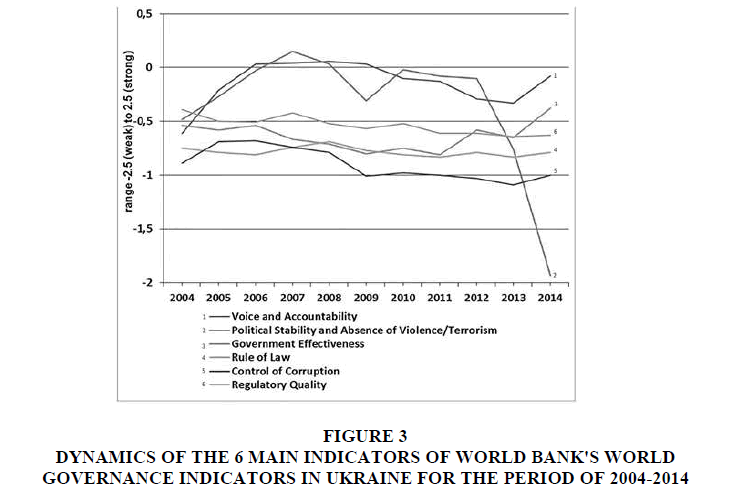

World Bank's World Governance Indicators demonstrate the impact of the political situation on the socioeconomic situation in Ukraine, which is presented in Figure 3 (Bank, 2014).

Figure 3: Dynamics Of The 6 Main Indicators Of World Bank's World Governance Indicators In Ukraine For The Period Of 2004-2014

The graphs show that, in contrast to other indicators, which have a neutral or positive development trend, the political stability index has taken a nose-dive. Since the data for this study was taken in the initial stages of the conflict, the revised version of index would likely show a negative trend in all key parameters.

The analysis of the indicators provides us additional information about the causes of the shadow entrepreneurship development. Despite some positive trends in 2013-2014, the value of the indices is lower than the conditional zero–the minimum level needed for sustainable and democratic development.

In Russia, situation has come about rather complicated in economic and social terms over the past decades. The majority of economic relations were disrupted, most significantly because of the collapse of the Soviet Union. In this regard, many enterprises fell out of their economic focus (Williams, 2009).

In Russia, situation has come about rather complicated in economic and social terms over the past decades. The majority of economic relations were disrupted, most significantly because of the collapse of the Soviet Union. In this regard, many enterprises fell out of their economic focus (Williams, 2009).

These factors sparked the shadow economy to extend wide in Russia. In particular, corruption (most significantly the bribery) has escalated.

Russian government should hold no the market reforms and support business development to reduce the shadow economy. Eventually, this will produce a result.

In Ukraine, one of the main reasons behind shadowing is the tax burden, but there are other equally important factors leading to negative social and economic consequences. These are a decrease in real incomes and living standards, traditional economic indicators that characterize the efficiency of social production are downhill, there are no internal sources of accumulation, while the socio-economic management is in crisis (Williams, 2009a: 2009b).

We suggest overcoming the shadow economy in Ukraine by legalizing the functions of government agencies, designing a state program against corruption, increasing punishment for financial and economic fraud, ensuring personal liability of state-owned/private enterprise administration for unlawful and inefficient diversion of funds, designing tax system in such a way that it contributes to a stable investment policy, maintaining investment insurance and state guarantees, and by rising performance standards for law enforcement and judicial bodies.

Conclusions

The formalization of the shadow entrepreneurship leads to growth of fiscal revenue. The reasons, which further the transition towards shadow entrepreneurship, should be considered in order to pursue an effective policy.

Indirect methods of measuring the shadow economy do not provide information about its forms and structure. Survey method is too expensive to use it constantly. Comparative analysis of international indices showed that they could be used as indicators of the problems that contribute to the emergence of shadow businesses.

The high level of corruption, taxes and bureaucracy are the main problems for Russia. Due to these problems, even large firms close their transactions in the informal sector. The main cause of the high level of the shadow economy in Ukraine is the lack of trust in the government. The unstable domestic policy, inability to resolve conflicts and protect national interests, lack of faith in the justice system are the reasons that make Ukrainian entrepreneurs to work in the informal sector.

References

- Aidis, R., Welter, F., Smallbone, D., & Isakova, N. (2007). Female entrepreneurship in transition economies: The case of Lithuania and Ukraine. Feminist Economics, 13(2), 157-183.

- Bajada, C., & Schneider, F. (2005). Size, Causes and Consequences of the Underground Economy: An international perspective. Gower Publishing, Ltd.

- Bergman, M., & Nevarez, A. (2006). Do audits enhance compliance? An empirical assessment of VAT enforcement. National Tax Journal, 59(4), 817-832.

- Bhattacharyya, D.K. (1999). On the economic rationale of estimating the hidden economy. The Economic Journal, 109(456), 348-359.

- Blackburn, K., Bose, N. & Capasso, S. (2012). Tax evasion, the underground economy and financial development. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 83(2), 243-253.

- Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2012). Shadow economies around the world: Novel insights, accepted knowledge and new estimates. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 139-171.

- Buehn, A., & Schneider, F. (2013). Shadow Economies in highly developed OECD countries: What are the driving forces? Economics working papers, 1-31.

- Capasso, S., & Jappelli, T. (2013). Financial development and the underground economy. Journal of Development Economics, 101, 167-178.

- Clausen, B., Kraay, A., & Nyiri, Z. (2011). Corruption and confidence in public institutions: Evidence from a global survey. The World Bank Economic Review, 25(2), 212-249.

- Conditions, W. (2016). The size and development of the shadow economies of Ukraine and six other eastern countries over the period of 1999-2015. Economy of development, 2(78), 12-20.

- Coupe, T., & Obrizan, M. (2016). The impact of war on happiness: The case of Ukraine. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 132, 228-242.

- Dickerson, C.M. (2011). Informal-sector entrepreneurs, development and formal law: A functional understanding of business law. American Journal of Comparative Law, 59(1), 179-226.

- Dreher, A., Kotsogiannis, C., & McCorriston, S. (2009). How do institutions affect corruption and the shadow economy? International Tax and Public Finance, 16(6), 773-796.

- Elbahnasawy, N.G., Ellis, M.A., & Adom, A.D. (2016). Political instability and the informal economy. World Development, 85, 31-42.

- Feige, E.L. 2007. The underground economies: Tax evasion and information distortion. Cambridge University Press.

- Feld, L.P., & Larsen, C. (2005). Black activities in Germany in 2001 and 2004: A comparison based on survey data. Rockwool Foundation Research Unit.

- Feld, L.P., & Schneider, F. (2010). Survey on the shadow economy and undeclared earnings in OECD countries. German Economic Review, 11(2), 109-149.

- Friedman, E., Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. (2000). Dodging the grabbing hand: The determinants of unofficial activity in 69 countries. Journal of public economics, 76(3), 459-493.

- House, F. (2016). Freedom in the World 2016: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield,

- Gorshenin Institute. (2016). Sociological survey “Social and political sentiments of Ukrainians”.

- Ilahiane, H., & Sherry, J. (2008). Joutia: street vendor entrepreneurship and the informal economy of information and communication technologies in Morocco1. The Journal of North African Studies, 13(2), 243-255.

- International, T. (2015). Corruption Perceptions Index 2015.

- Johnson, S., Kaufmann, D., Shleifer, A., Goldman, M.I., & Weitzman, M.L. (1997). The unofficial economy in transition. Brookings papers on economic activity, 159-239.

- Kirchgässner, G. (2016). On Estimating the size of the shadow economy. German Economic Review.

- Maritz, A. (2004). New Zealand necessity entrepreneurs. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 1(4), 255.

- Muehlbacher, S., & Kirchler, E. (2010). Tax compliance by trust and power of authorities. International Economic Journal, 24(4), 607-610.

- Murphy, K. (2005). Regulating more effectively: the relationship between procedural justice, legitimacy and tax non-compliance. Journal of Law and Society, 32(4), 562-589.

- Schneider, F. (2016). Comment on Feige’s Paper' Reflections on the Meaning and Measurement of Unobserved Economies: What Do We Really Know about the'Shadow Economy'?'.

- Schneider, F. (1994). Measuring the size and development of the shadow economy. Can the causes be found and the obstacles be overcome? In Essays on Economic Psychology. Springer.

- Schneider, F. (2005). Shadow economies around the world: what do we really know? European Journal of Political Economy, 21(3), 598-642.

- Schneider, F. (2010a). The influence of public institutions on the shadow economy: An empirical investigation for OECD Countries. Review of Law and Economics, 6(3).

- Schneider, F. (2010b). The influence of the economic crisis on the shadow economy in Germany, Greece and the other OECD countries in 2010: what can be done. Institute of Economics, Johannes Kepler University of Linz.

- Schneider, F. (2012). The shadow economy and work in the shadow: what do we (not) know? IZA Discussion Paper, 6423.

- Schneider, F., Buehn, A., & Montenegro, C. (2010). New estimates for the shadow economies all over the world. International Economic Journal, 24(2), 443-461.

- Schneider, F., & Schneider, F. (2004). The Size of the Shadow Economies of 145 Countries all over the World : First Results over the Period 1999 to 2003.

- Schwab, K. (2016). The Global Competitiveness Index 2016.

- Smallbone, D., & Welter, F. (2004). Entrepreneurship in transition economies: Necessity or opportunity driven. Babson College-Kaufmann Foundation, Babson College, USA, 9, 2010.

- The World Bank. 2014. Country Data Report for Ukraine, 1996-2014.

- The World Bank. 2016a. Doing Business 2016.

- The World Bank. 2016b. Doing Business. Economy Profile 2016 Ukraine.

- Torgler, B., & Schneider, F. (2009). The impact of tax morale and institutional quality on the shadow economy. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(2), 228-245.

- Torgler, B., Schneider, F., & Schaltegger, C.A. (2010). Local autonomy, tax morale and the shadow economy. Public Choice, 144(2), 293-321.

- Williams, C.C. (2009a). Beyond legitimate entrepreneurship: The prevalence of off-the-books entrepreneurs in Ukraine. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 22(1), 55-68.

- Williams, C.C. (2009b). The hidden enterprise culture: Entrepreneurs in the underground economy in England, Ukraine, and Russia. Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 44.

- Williams, C.C., & Nadin, S. (2010). Entrepreneurship and the informal economy: An overview. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15(4), 361-378.

- Williams, C.C., & Nadin, S. (2010). The commonality and character of off-the-books entrepreneurship: A comparison of deprived and affluent urban neighbourhoods. SSRN Electronic Journal, 15(3), 345-358.

- Williams, C.C., & Windebank, J. (2006). Harnessing the hidden enterprise culture of advanced economies C.C. Williams, ed. International Journal of Manpower, 27(6), 535-551.