Case Reports: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 2

Evolution of an Enterprise Information System Toward Omni-Channel Retailing: A Case Study

Varin Francis, Bryant University

Chaudhury Abhijit, Bryant University

Abstract

This case study covers the evolution of an enterprise information system at a sportswear firm. Over time, the sportswear industry has moved from a single channel to multiple channels and is now progressing toward an omni-channel system for better serving their customers. This required a corresponding evolution in the firm’s information technology (IT) systems. But changes in an IT system do not work in isolation. To get the most from their new IT platform, the firm discovered the need to redesign their organizational structure, redefine IT’s role, and do strategic workforce planning. The paper describes, under fictitious names, how the firm negotiated these challenges as it moved towards a new IT platform that would enable omni-channel offering to its customers.

Keywords

Enterprise Information Architecture, Multiple Channel, Omni Channel

Introduction

On Monday, January 11, 2010, Warren Prescott, the incoming CEO of White Mountain Sportswear (WMS), had a long meeting with board members, many of whom were members of the LeBeau family that started and continued to have majority ownership in the publicly traded firm. Mr. LeBeau, the current CEO, made Mr. Prescott aware of the firm’s history that spanned over a century. Mr. LeBeau emphasized that WMS always considered itself an integral part of the local community and had continued to use the same buildings and manufacturing shops that it started with. According to him, there was a “social compact” between WMS, its employees, its shareholders, and its vendors. They were like a family, and WMS had avoided any layoffs in its long history. Most of the executives hailed from the same town and went to the same colleges, and WMS generously contributed to the public institutions of the town such as schools, libraries, colleges, and parks.

According to Mr. LeBeau, WMS’s sales growth had recently become anemic. Their e-commerce venture was not meeting expectations. Sales in the e-commerce channel seemed to come at the expense of sales in the other two channels: stores and catalog sales. The LeBeau family felt that it was time for new blood that had experience with the retail revolution sweeping the world-hence their recruitment of Mr. Prescott as the new CEO. Mr. Prescott was hired from a current competitor of WMS, so he had some ideas as to what ailed the firm. Mr. LeBeau wanted to know Mr. Prescott’s opinion of the current retail scenario. “Every generation has its retail revolution,” remarked Mr. Prescott. “It has a lot to do with technology, a new generation of customers who are looking for something different and firms who don’t get it right” Sarker (2000).

At the end of the meeting, Mr. Prescott felt that the firm needed to be revitalized with a new information technology (IT) platform. But he also knew that, as in a chess game, the major pieces must move in concert with minor pieces to end in success. So, new IT alone would contribute little. The current CIO of the firm, Mr. Peter Stingley, was professionally known to him. Mr. Stingley previously worked as a CIO in a large retail firm and had a good reputation; Mr. Prescott felt that he was the right man now (Leavitt, 1965).

History: 1890 to 2010

Following the immigration of French-Canadians during the 19th century, Henri LeBeau began manufacturing sportswear in the late 1890s. LeBeau’s love of the outdoors and his background working in the textile industry in New England provided him with the necessary understanding and expertise to establish such an enterprise. His small shop in Southbridge, Massachusetts, provided him with ample space to produce a small variety of apparel. LeBeau’s products gained recognition from outdoor enthusiasts as affordable and of exceptional quality.

Within a few short years, his new company had grown considerably, and it was able to sustain profitability during the Depression and into the 1930s. LeBeau moved to a larger facility in Southbridge and doubled his staff, enabling the company to have a regional impact. The company was given the name White Mountain Sportswear, reflecting LeBeau’s love and passion for the White Mountains of New Hampshire, a prime location for activities such as skiing and hiking. WMS utilized mail-order catalog sales to expand their reach throughout New England.

By the 1970s, WMS had increased their product line substantially to serve markets beyond just outdoor enthusiasts. Many workers in the New England fishing and construction industries were using WMS’s products. In response, WMS established a workwear division to focus on this new market opportunity. Mark Spencer, Assistant Vice President of sales, was named to manage the new division and promoted to Vice President. Under his leadership and working closely with LeBeau, the workwear division steadily grew into a viable market segment for WMS (Pereira & Sousa, 2004).

The 1980s and 1990s marked a time of significant growth for WMS. They had expanded to over twenty retail stores in the US and four in Europe. In 1989, they suddenly faced a 300% increase in call volume during the Christmas holiday season, which had the potential to swamp the call center with order and customer service inquiries. WMS responded by purchasing a warehouse that was wired as a call center. From then on, six weeks before the annual busy season, WMS would hire temporary workers to operate the phones. The annex to the main call center was dormant most of the year and only used during the busy season. Due to significant growth and to address technological changes, WMS also introduced a mainframe computer system to manage inventory, accounting, order processing, and fulfillment Zhe (2018). Through careful planning and strategic decision making, WMS achieved the goal of improving the speed and efficiency of their business operations as their sales increased.

WMS’s growth began to level in the late 1990s. To address the increase in volume and the rising cost of labor, WMS moved most of their manufacturing overseas. Plants in China and the Philippines were added to the original factory in Southbridge, MA. The change in approach to include manufacturing abroad presented challenges WMS had not anticipated or understood. Time zone differences allowed extended hours for manufacturing to take place, but impacted communication between the headquarters and the satellite plants. WMS began to realize the savings in labor they had anticipated, but some early quality issues had negative effects on their brand’s position in the market, with a negative impact on revenue and sales. Once the issues were addressed, the sales and revenue numbers recovered quickly. WMS was faced with understanding the culture and society in the new plant locations. Initially, this led to misunderstandings between those managing the offshore plants and the management stateside. It took a while, but once a highly collaborative partnership between the management teams had been established, the working relationship began to iron itself out. In the end, it took WMS much longer than expected to get the overseas plant operations performing at an anticipated level, requiring the management team to be focused exclusively on this task at the expense of other business initiatives (Wells, 2013).

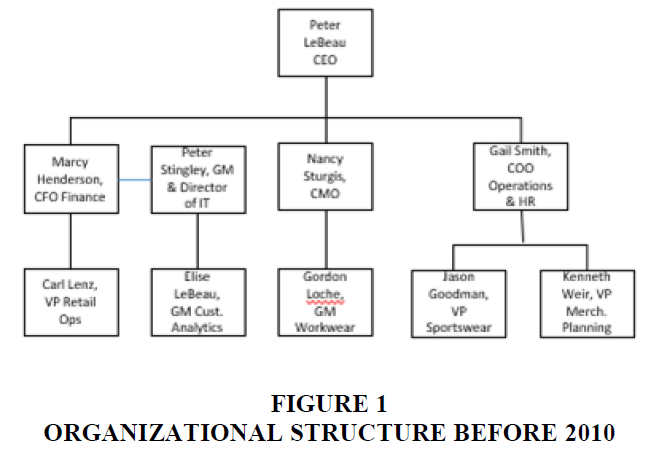

Upon the retirement of Peter LeBeau, the board of directors decided to hire a CEO from outside the company to address the issues facing WMS. They chose Warren Prescott, who had been the COO of Harper Actionwear, WMS’s main competitor. Harper Actionwear was more progressive in their management approach than WMS had traditionally been, and the board felt Mr. Prescott would introduce necessary changes that would benefit the company. During the last few years of his tenure, Mr. LeBeau had brought in several senior executives from outside, including Marcy Henderson as Chief Finance Officer and Nancy Sturgis as Chief Marketing Officer, both around the year 2004. While the workwear division came under Ms. Sturgis, the sportswear division continued to operate under the Chief Operating Officer, Gail Smith. Elise LeBeau, the youngest daughter of Peter LeBeau, was promoted to manage manufacturing. Peter Stingley was hired in 2005 as head of the IT department shown in Figure 1.

Taking Stock

In his first few days, Mr. Prescott met with senior managers of the firm. He realized from these meetings and from competing against WMS in his previous job that the firm continued to enjoy many strengths. They had a very reputable brand, legendary customer service, and warranty policies that were the most liberal in the industry. For their size, they had one of the largest call center operations in the industry, whose employees were all natives of Massachusetts. WMS often received awards for its customer service quality. Its operating margins were healthy, but its market share had progressively reduced with the entry of new firms and the e-commerce revolution that Amazon exemplified (Keil & Mahring, 2010).

Employees of WMS were conscious that change was necessary but were apprehensive as to how it might affect them individually. The esprit de corps that Mr. Prescott sensed among the managers, most of whom grew up in the same town, meant that if inspired by the right strategy they would deliver outstanding performance. With a successful e-commerce operation coupled to their retail stores in Europe, there was a great opportunity to go beyond the US market.

WMS’s weakness as compared to its competitors was a relatively outdated IT platform, but Mr. Stingley had accomplished some notable changes in his last five years with WMS. The new CFO and COO who had joined along with Mr. Stingley were enthusiastic supporters of the IT changes being implemented. They installed SAP systems that allowed integration of their operations with vendors all over the globe. This led to integration of WMS’s supply chain with its vendors’ supply chain systems. The store managers had the benefit of access to current data about product availability in their central warehouse in Sturbridge, and the procurement managers had current data on stocks in stores and warehouses Applegate and Montealgere (2018).

While WMS’s products were first rate, Mr. Prescott realized that no one spoke much about “customer experience,” the buzzword sweeping the retail world. Consumers now expected an excellent online shopping experience with order fulfillment and delivery within days. Consumer preference had changed. They expected an organization to know them well and tailor products to anticipate their future needs. Shoppers’ experience had now become the driver of competition, and that was not reflected in WMS’s organizational structure, systems, or culture. Their marketing focus continued to be on product quality and service, even though because of outsourcing most retail firms acquired their products from similar sources, which made differentiation harder to attain.

Managers were mostly employees with over 20 years of service at WMS, often working in the same department and in the same product line. They had a strong tradition of doing everything in-house to ensure the quality that their customers expected. Few managers showed interest outside their individual lines of work and departments. With the siloed outlook of the managers and lack of cross-functional or product experience, Mr. Prescott wondered how much of the promised process integration by SAP really led to a more dynamic decision-making environment in the firm.

E-commerce Channel

During the Internet boom of the late 1990s, WMS decided to utilize a website to expose their catalog. They set up an office in New York and started an e-commerce channel from that office, using a local firm to run the website and e-commerce platform. Unfortunately, the firm went bankrupt in the 2000 dotcom bust. WMS’s own IT department managed the website for some time before another e-commerce specialty firm was hired. Order processing in this channel was still strictly handled by phone or emails from the New York office to their distribution center in Sturbridge.

WMS prided themselves on high customer touch and service and maintained a conservative approach in their implementation of the online channel. This decision was due to the older technology WMS continued to use, which was in the process of being replaced by SAP systems related to fulfillment and warehousing. WMS did not consider themselves an early adopter of new technology in a time when most executives were not sure business would thrive in the new online e-commerce world. Eventually more organizations began to drive business to the Internet, attempting to keep pace. WMS did not pursue increased investment in their online channel due to other higher-priority business initiatives. As a result, WMS’s presence had not significantly changed since their first offerings, and their competition moved past them. What once was an early advantage for WMS now placed them behind their competition. WMS recognized the signs of customer erosion due to their weaker position in the new online economy.

WMS maintained the website for years but invested no business focus or commitment to develop it as a valid marketing channel, resulting in little functionality on the site that was of interest to consumers. The e-commerce share of their business initially grew fast to around 20% by 2004, and then saw little improvement. Much of the sales in the e-commerce channel came at the expense of existing catalog sales, and that did not generate much enthusiasm at the head office. Their competitors’ e-commerce share was close to 50%, showing the potential for improvement if they could get this channel right. The channel had seen three managers in 10 years, who all came from the sportswear and workwear divisions and went back to their old departments. The pricing decisions for the e-commerce channel were made by the division managers of sportswear and workwear. Often, the retail price and the web price were the same, but with the added cost of shipping, the final price to the web customer was higher. So, while the e-commerce channel manager was responsible for the channel sales, most decisions were out of their scope of authority. For changes in pages and layouts, the e-commerce channel manager had to route their requests through the product managers, which added delays that they could ill afford during the brief holiday season. When it came to poor sales in e-commerce, there was no single point of accountability in the whole firm. Their SAP FI/CO (financial and control) system was configured to have two sales areas for the two product divisions, for which their individual profitability and revenue were computed, and so numbers for e-commerce were at best estimates. Current estimates of sales data in the e-commerce channel were only available at the end of each month.

One of the persistent complaints of web customers was late deliveries. To improve the situation, WMS set up a warehouse in the New York area that stored most common items ordered. This allowed quick deliveries, as shorter delivery times were becoming a critical differentiator due to initiatives launched by Amazon. This warehouse was not part of the SAP system, and the warehouse management systems at the New York warehouse and their main distribution center in Sturbridge were from different vendors. The warehouse logic for systems supporting retail sales is very different from that supporting e-commerce. In retail sales distribution centers, goods move in and out on at least a pallet basis. In contrast, in the e-commerce world, items are picked and shipped a few at a time. The logic of storage in e-commerce warehouses is not pallet based, but as bundles of a few items irregularly laid out near the packaging section, according to the frequency of ordering. A single order in e-commerce may have three different items with a quantity of one each, and the picking logic needs to disaggregate the order first, collect each item separately, and aggregate the items into a single package, which then must be handed out to a shipper. In contrast, in the retail store, all this “last mile” activity is done by the customers themselves. For e-commerce warehousing, this kind of picking and packing activity leads to either expensive labor or expensive automation, and small scale operations such as WMS are at a competitive disadvantage against firms like Amazon that enjoy scale economies. When WMS’s products were not available at the New York warehouse, which happened frequently, they were obtained from the distribution center in Sturbridge, which added to delays. Moreover, these sales were not credited to the e-commerce channel, which led to even poorer sales figures for the new channel.

Over time, WMS had adopted Google Analytics to track and understand the issues with the new channel. The Google search ranking for their products was lower than their competitors’. They occasionally hired search engine specialists to assist in their web design. It would work for some time, but when the search engine algorithms changed, the gains would be lost. Traffic came from all over the US, but most of the sales were from cities on the East Coast, which showed that WMS was failing to enhance its customer base. Sources of traffic were weighted towards social media and various search engines, but WMS had scant social media presence and tracking. Products that were popular over the web were not often the same products that were popular in retail stores, pointing toward different demographic groups in the two channels. The site suffered from poor conversion rates, with many pages having high bounce rates. The sourcing devices were increasingly cell phones, and the page load times were often poor on these devices, leading to high cart abandonment rates.

The New Vision

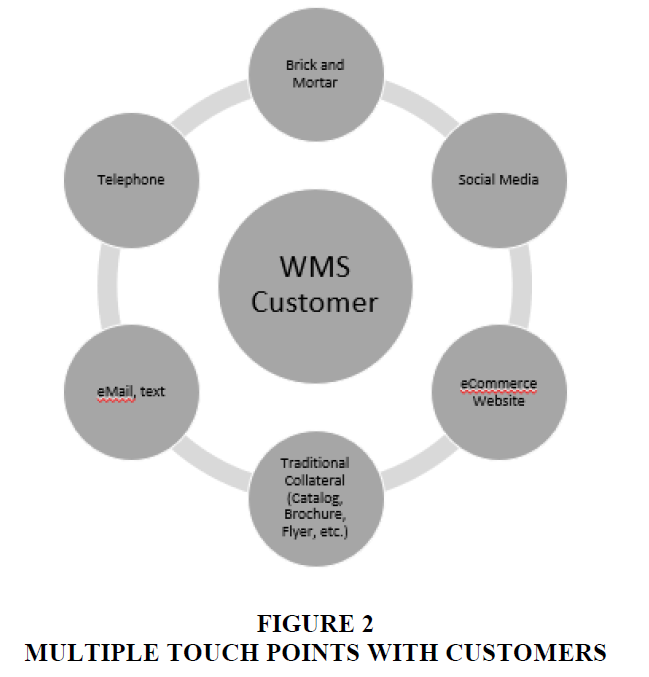

Mr. Prescott started selling the vision of WMS offering the most “outstanding and delightful multi-channel experience to its customers” in the sportswear industry. A customer’s experience is made up of individual touch points, over a variety of channels (Figure 2) that need to seamlessly connect, allowing them to pick up where they left off on one channel and continue the experience on another. Only then could an experience be classed as delightful.

Mr. Prescott started emphasizing systems, structure, and solidarity as enabling factors for achieving the vision. WMS needed a new IT platform that was in tune with the times. In Mr. Stingley, he had a competent manager who could lead the initiative. Changes in organizational structure were needed to best use the potentiality of the IT platform. He wanted to develop a structure made up of individual organizational units where accountability and authority were closely aligned and a reporting system that provided current performance numbers for these organizational units. Dealing with a 100-year-old company that had fiercely loyal employees, he wanted to assure them that while much change would happen in individual roles and functions, there would be no layoffs. He knew that he would face strong resistance in implementing the new structure and systems from multiple stakeholders of the firm, such as senior managers, front line employees, IT staff and vendors, and an impatient financial community. He decided to anticipate their reactions and take early steps to defuse them.

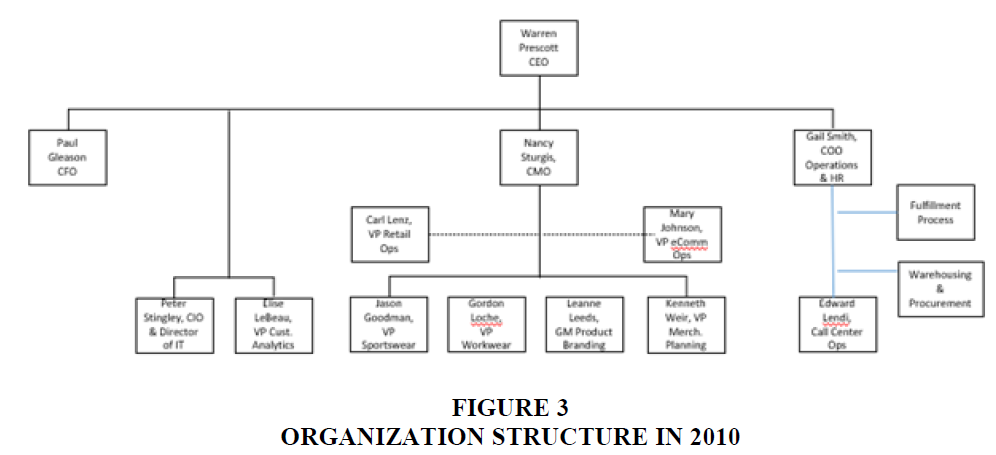

Over many meetings, it was decided that there should be two managers for the two product divisions and two separate managers for the two channels. SAP allowed sales areas as combinations of divisions and channels, and with two channels and two divisions, four sales areas could be tracked by the SAP system. Therefore, the revenue and profitability of the four sales areas could be tracked in real time simultaneously. Pricing decisions would be made jointly by the concerned channel and division managers as in a matrix organization structure. All four division and channel managers would be reporting to the Chief Marketing Officer (Figure 3), who would have a dashboard showing weekly and monthly sales and margin data for various product lines and channels and combinations thereof. There would be dedicated employees for the two channels, and new experienced employees would be recruited for the New York office.

WMS had used Accenture for their SAP implementation, and they would act as consultants when WMS upgraded their e-commerce channel. Key performance indicators were identified for the e-commerce channel, such as sales, traffic, conversion rates, load times, etc., and reporting systems were to be developed accordingly. It was decided to use Accenture as their main IT vendor for multiple reasons. Accenture had over 40 years of collaboration with SAP, and they were the consultant for WMS’s implementation of SAP modules like FI/CO, HR (human resources), materials management, and so on. Accenture had a big presence in their Massachusetts office, their retail implementation of SAP system was becoming popular in the industry, they were familiar with WMS, and top officers at WMS were satisfied with Accenture’s performance.

It was decided that the current warehouse in New York would be moved to Sturbridge, adjacent to the existing distribution center. The two warehouses would share inward delivery systems but would have different picking software with different packing and shipping centers. With the two warehouses next to each other, it would be easier to share items among warehouses. Over time, the two warehouse software systems would be merged into a single system that could coordinate the two and connect to SAP’s material management system that was being implemented. Ms. Smith suggested that they consider drop-shipping form US-based suppliers for items such as leather belts, and jackets that were popular on the web as that would save time. WMS nay even offer to these vendors their warehouse facilities for them to sell under different labels.

To Mr. Prescott, employees’ loyalty to WMS was a major source of strength. Over their long history many retail revolutions had happened, and WMS had always survived and come out stronger. This was a resource that Mr. Prescott as a CEO wanted to cultivate and harness. He knew he had to communicate in depth and communicate often on all the changes that were being considered. He started a monthly newsletter and held periodic town hall meetings with the employees and encouraged department managers to do likewise. They were encouraged to identify employees who were technologically savvy and could be trained to play technology leadership roles. Frequent training by vendors and exposure to their presentations were initiated. The SAP implementation of FI/CO, HR, and the core fulfillment process S&D (sales and distribution) had built a stock of experience of how to introduce major changes in the firm. Since SAP led to no layoffs and most employees seemed to enjoy the new roles they had to adopt, it was a positive and assuring experience Mr. Prescott wanted to build on. He had his HR staff conduct frequent surveys to keep tabs on employee morale and their concerns.

The SAP HR module consisted of organizational units where different positions were identified by different skill sets, experiences, and education. Mr. Prescott and Ms. Smith got a skills inventory chart developed, and HR then worked on what the prospective chart would look like in five years. The difference in the two charts helped identify gaps that needed to be filled. Ms. Smith brought individual department managers into the exercise. It was hoped that in the final document, different managers would see their own input. Workforce planning had a strong negative connotation, and their participation would take the sting out of it, Mr. Prescott hoped. These reports were widely circulated throughout the firm to show the employees where there were excesses, and where new opportunities were opening. Mr. Prescott hoped that this kind of transparency would help reduce resistance from employees when new IT systems were rolled out.

IT’s New Role

Mr. Prescott and Mr. Stingley had long discussions on the role IT would play in the new vision of providing the best multi-channel experience in the industry. The other C-level executives were brought into the discussion. They were impressed by Mr. Stingley’s knowledge of multi-channel systems and knowledge about what the competition was doing. Mr. Stingley studied IS in college and later earned an MBA from a reputed school in New York.

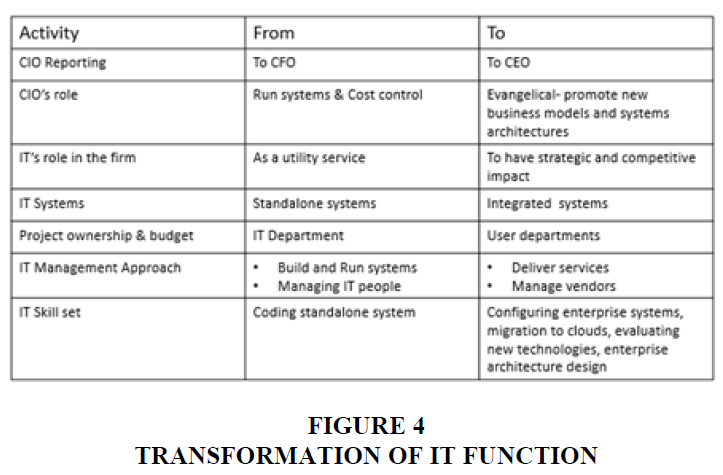

Senior managers recognized that IT needed to improve its visibility and adopt a more active and prominent role in the firm. It helped that Mr. Stingley had a simple demeanor and did not threaten to upstage the line managers with his proposals. It was agreed that IT was in the best position in the firm to identify the technology changes that were driving the retail industry. It was decided that Mr. Stingley would be one of the new C-level executives, making four-C level managers in the firm: Finance, IT, Marketing, and Operations shown in Figure 3. All realized that taking IT out from under Finance would give the IT department more teeth in the organization and let all know that Mr. Stingley enjoyed the full support of Mr. Prescott and the governing board. It was expected that the cultural problems would be tough for managers in IT who were used to working like utility service personnel. IT needed to become a place where these managers were ready to help drive the company forward.

Since its inception, WMS had viewed IT as a cost center where business units dictated what technology was to be used and when. Technology and the “data processing” department had not been viewed as significant enough to leverage as a strategic business advantage. This approach served WMS well until the 1990s, but IT’s role would now be more evangelical, where the department would bring in vendors and consultants to display to WMS managers all the possibilities that were emerging and what their competitors were adopting shown in Figure 4. The IT department’s focus needed to change from developing software and running applications to helping develop services in line with the corporate vision. With the new systems redefining users’ activities, there was a high risk of user resistance and reluctance to adopt new systems, and so ownership of new systems was transferred to the functional departments. With cloud based SaaS (software as application services) becoming increasingly popular, WMS could implement cutting-edge solutions without spending on hardware and software development. In delivery of services, vendors now had to play a more prominent role.

In the new IT department, the focus of activities would evolve to include managing multiple projects, with vendors implementing many of them.

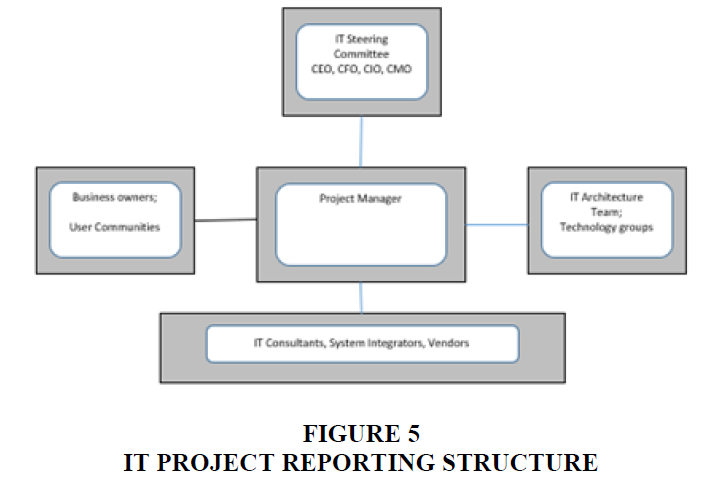

To keep project implementation aligned with their new role, project implementation and reporting were changed shown in Figure 5. Many of the projects were now strategic in nature. An IT steering committee was constituted that included all four C-level executives of the firm. Individual project managers were to report on a monthly and quarterly basis to the steering committee. There were other stakeholders for each project, for whom roles were identified and the communication and reporting frequency was established. For projects that were not infrastructural in nature, like having new servers and networks, the important stakeholder was the department that acted as “owner” of the project, and the project would now be part of their budget. It was decided that no non-infrastructural project was to be launched until a department was willing to bear its costs, signed on to it, and was responsible for its successful rollout. From now on, the IT department would act like as an internal vendor to the owner department and the primary responsibility for success would rest with the owner department. Whether executed by the WMS IT department or by vendors, projects were to adopt the agile methodology as much as possible, because that would allow the owner and the user community to stay in the loop. Every new prototype developed required the owner department to sign off on the current design and development.

New Enterprise Information Architecture

In reviewing the evolving plan for a new IT platform with her four VPs for the two divisions and the two channels, Ms. Sturgis remarked, “We will need to be the agent driving change for achieving our new vision of delivering a unified superior experience throughout every interaction. After all, customers, who they are, and what they want is what we know best.” With the firm evolving toward centering on the customer and customer experience, many of the building blocks in the IT platform would be customer focused, they all realized.

In their next monthly meeting with Mr. Stingley and his managers, there was much curiosity as to what new software applications IT had in mind and how it would affect their work. Mr. Stingley introduced the concept of enterprise information architecture (EIA). He described it as a plan, a document that bridged the world of business and technology. An EIA described how the business services were the result of a combination of IT building blocks and how the change in business model and way of doing business needed to be foreshadowed in the EIA diagram. Simply put, the EIA described what services IT would provide, how those services would be generated by a combination of IT elements, where they would be located, and when they would be implemented. So, enterprise architecture design was an activity that aligned a firm’s business strategy with technology plans that would support it. Its documents should be able to address both technical experts and business stakeholders and describe how technology systems architecture help achieve business goals in in a holistic fashion. EIA facilitated management of change by relating strategic requirements to information systems that supported them and by linking parts of the business model to IS applications portfolio.

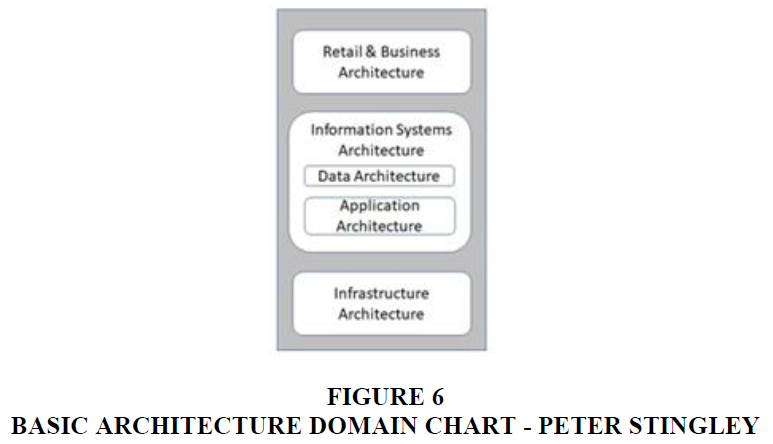

Stingley pointed to the diagram shown in Figure 6. “We can think of WMS as having a high-level architecture which is comprised of three distinct architecture domains which not only rely on one another but are stacked vertically… like this”. Stingley continued, “With this in mind we can see how our current infrastructure and architecture supports our current retail business.” At the top level was the retail and business architecture: the business activities that constituted the firm. On the middle layer was the data architecture: the applications that interacted with the database on one side and with end users on the other side so that users could engage in the activities broadly described in the top layer. On the bottom layer was the hardware: networks and servers that allowed the second layer to perform. These were not directly visible to the user.

In describing the top, retail and business architecture, Mr. Stingley, drew attention to their point of sale systems and the catalog center and the call center applications which is part of the top layer. They were served by a common information system backend with its own data architecture and applications, the second layer. This stores backend layer connected to the corporate systems, which were SAP based and provided the functionality for order fulfillment, finance, accounts, human resources, etc. However, different sales channels suffered from price discrepancies and availability figure because different channels were working off to different versions of the data. Business channels had historically developed independently with their own departments, budgets and managers and ended up with their own information systems that served their specific needs the best. This resulted in a mish-mash of connections between the second layers where the data and the business applications resided and the top layer that served the customers and the employees that were interfacing the customers.

Stingley added, “When we have a modern architecture and infrastructure, it would be simply a matter of enabling new communication channels within our applications through our architecture and infrastructure. That is not always possible given our current configuration. Essentially, in our new configuration we will have a single pipe that connects the two layers so that the top customer facing layers are working off a single version of data. That would be fundamental in making customers have a seamless experience as they switched from one channel to another in their interaction cycle.

Mr. Stingley explained how the new proposed architecture would allow evolution of the marketing function. Increasingly, customers are in a single buying experience end up using multiple channels such as web, email, physical stores and multiple devices such as cell phone tablets and laptops. Currently, the data related to each touchpoint gets stored in different tables and in different formats. Providing an omni-channel experience would require that a unified view of all these touchpoints be available to the customer relationship management applications. The SAP platform worked off a single integrated database so with the right CRM module all interactions with the customer, including the customer’s orders, historical and pending, all the issues raised with the customer service, all the products they have browsed can be loaded into a single set of tables and can be made available to anybody in WMS in real time, which is known as the 360-degree view of the customer. With the right analytics running over the data, they could easily identify their most valuable customers, an important goal of a CRM system, and provide them with the best services and prices.

It was the end of December 2010. The end of the first year for a new CEO is a weighty occasion when employees and board members reflect on what was achieved and how far they have traveled under the new leadership. Mr. Prescott reflected that WMS seemed to have adopted the new vision: that customers’ experience cycle needed to be delightful across multiple channels. Mr. Prescott hoped that the entire firm was now on the same page when it came to realizing the centrality of customers and their experience in driving IT and structural changes in the firm. Mr. Prescott liked to describe his approach as offensive-defensive in nature: offensive in that the firm constantly scanned for new opportunities and reoriented itself to seize them, and defensive in that it anticipated the blowback this would trigger from its stakeholders and took steps to ameliorate it. Only time would tell if his offensive-defensive approach worked for WMS or not.

Instructor’s Manual

Case Synopsis

This case study covers the evolution of an enterprise information system at a sportswear firm. Over time, the sportswear industry has moved from a single channel to multiple channels and is now progressing toward an omni-channel system for better serving their customers. This required a corresponding evolution in the firm’s information technology (IT) systems. But changes in an IT system do not work in isolation. To get the most from their new IT platform, the firm discovered the need to redesign their organizational structure, redefine IT department’s role, and do strategic workforce planning. The paper describes, under fictitious names, how the firm negotiated these challenges as it moved towards a new IT platform that would enable omni-channel offering to its customers.

Learning Objectives

1. Evaluate the nature of competition in an industry and identify the role information technology can play in developing a successful competitive response.

2. What is entailed in installing a new IS platform? What business and organizational problems are likely to emerge? How do you cope with them?

3. How does the role of an IS department change as a firm gets more technologically intensive?

Epilogue

WMS’ performance in terms of sales and market share steadily improved over time. The lag they had in IS implementation against their principal competitors like Harper Actionwear was progressively bridged. The share of e-commerce improved to 40% which was close to industry average but still not up to the level that Mr. Prescott had planned. To boost that share, Mr. Prescott opened a warehouse in Ireland and commenced e-commerce operations in Europe. The effect of Amazon on the retail sports clothing industry continued and the proportion of market share held by the retail stores in their winter sports clothing segments continued to decline. After much deliberation, WMS decided to use the Amazon platform. An important proportion of those sales on Amazon were for high end products that were sourced from Europe and were part of the lines that were also very successful in their e-commerce operations in Europe. It seemed that for products that were available on WMS e-commerce platform in the US, the customers preferred to shop on WMS’ web site and not on Amazon.

Case Questions

1. Do a Porter’s five forces analysis of the sportswear retail industry. Do you think it is a profitable industry? Why?

Porter’s five forces analysis is done at the industry level. For the winter sportswear retail industry, this is how the five forces evaluate.

| FACTORS | COMMENTS |

| Rivals | There are several who are mostly of similar size and focused on winter wear. There is a larger retailer that also sells winter sportswear. But the emergence of Amazon in the field has made rivalry in the industry more intense. |

| Customers | Some are brand sensitive which is positive for firms with strong brands. But the ones who are price sensitive have in Amazon a new source of supply. The younger demographics is turning towards Amazon and other e-commerce channels |

| Suppliers | The suppliers and their agents in Asia are many and therefore have little negotiating power |

| Substitutes | Substitutes are none for somebody interested in winter sports but pricing beyond a certain level would make the sport less popular |

| New Entrants | For new entrants particularly, ones appearing with an e-commerce channel there are few barriers to entry. So, this is an adverse factor |

According to above qualitative study, most factors are adverse, and the profitability of the winter sportswear industry is worsening over time. A major reason has been the emergence of e-commerce.

2. Do a SWOT analysis of WMS beginning in 2010. What business strategy would you advise

| FACTORS | COMMENTS |

| Strength | • WMS has strong brand, • a reputation for excellent customer service, • has employees and managers who are dedicated to the firm, • Their IT department has developed the skillsets to implement complex enterprise systems supplied by SAP. • Being part of the SAP world provides them with access and skill to implement the customer facing solutions that are emerging in that ecosystem. |

| Weakness | • Their information systems are not as up to date as the best in the industry. • The IT department is viewed as a cost center with limited role in strategy formulation. • WMS e-commerce venture did not prove successful showing limitation in structure, systems and processes in the firm. • Compared to firms like Amazon and Walmart, they are a firm with limited resources |

| Opportunities | • Emergence of new technology platforms is much a threat as an opportunity. • Being ahead on the technology curve will allow WMS to provide services that will help to differentiate them against their competitors. • E-commerce will help them to leverage their expertise in retailing winter sports wear into new geographies such as Asia and Europe. |

| Threats | • Emergence of Amazon is changing the competitive landscape in a negative way. • The younger demographics are more into e-commerce and using multiple devices which WMS is yet to be able to serve |

Strategy: WMS can only survive through differentiation. The strategy of differentiating oneself through product excellence only has run its course because same sources are serving multiple retailers. The strategy of delivering an excellent shopping experience has also run its course as the new demographic lives and shops in the digital space. For WMS that is the space of competition where it has to make its mark.

3. Prescott limited himself to three factors: systems, structure, and solidarity for achieving his business vision. What factors would you have preferred?

It is implicitly assumed that the environment in which WMS is operating will be stable and that factors such as good economy, increasing globalization, long supply chains, etc., will all be as it is. But they did not and in a single election cycle much changed.

While Mr. Prescott has ensured that the top management has bought into his vision, there is little evidence in the case, that WMS is taking steps to see that change is accepted by all levels of employees. Even the best strategy can flounder if employees do not buy into it.

Dependence on IT driven strategy brings along its own risk factors. The multi-dimensional skill set in multiple IT areas required of the firm is still not there. It is very hard to retain the skilled IT employees. Changing their skill profile is a slow and challenging task.

4. What role did IT play in Mr. Prescott’s new vision?

Mr. Prescott realized that the space of competition is now the digital space. That space of operations is now IT driven which needs to be installed, configured, and then sold to employees who will be trained on them. The knowledge of the emerging digital solutions is primarily with the IT vendors. That information flows from the vendors to the IT department of the firm, who participate in configuring and installing the systems with the operational people in a way that meets the business requirement of the firm. This knowledge within the firm moves from the IT department to the functional departments. So, the IT department plays a critical role in acting as a midwife for a firm adopting new ways of doing things

5. Why did he feel the necessity of reconfiguring the IT department and its role?

In WMS, IT was treated as a cost center with the role of providing services that is expected of departments like power or air-conditioning or HR. These departments are not into fundamentally how the firm operates. As a new platform, the role of the visibility of IT goes up in the firm and as the platform matures that role is reduced over time. As of now IT needs to be involved in most operational areas of the firm and that role must be formally introduced into the structure of the firm.

The knowledge of digital solutions is generated in the vendor firms like SAP. That knowledge diffuses to firms through their IT departments who talk the same technical language. From the IT department, it then diffuses to user departments. The IT department needs to have the stature to make that diffusion process effective at all layers of the management including the C-level executive committees. During this phase when a new platform is being introduced, much of the CaPex expenses of the firm is in the IS field. Over time as the platform matures, such CaPex expenditures reduce and the IS department’s importance to the firm becomes less critical, until it is time again for another new technology platform. The role and visibility of the IS department waxes and wanes in line with life cycle stage of the IT platform.

6. Do you think Mr. Prescott’s offensive-defensive approach would work? What actions in the case would count as offensive and what actions would count as defensive?

It can vary.

References

- Sarker, S. (2000). Toward a methodology for managing information systems implementation: A social constructivist perspective. Informing Sci. Int. J. an Emerg. Transdiscipl, 3, 195-205.

- Leavitt, H.J. (1965). Applied organizational change in industry, structural, technological and humanistic approaches. Handbook of organizations, 264.

- Pereira, C.M., & Sousa, P. (2004). A method to define an Enterprise Architecture using the Zachman Framework. In Proceedings of the 2004 ACM. symposium on Applied computing, 1366-71.

- Zhe, P. (2018). IT change management practices. Retrieved from https://www.cio.com/article/3324368/12-it-change-management-practices.html.

- Wells, J. (2013). Strategic IQ: creating smarter corporations. John Wiley & Sons.

- Keil, M., & Mahring, M. (2010). Is your project turning into a black hole? California Management Review, 53(1), 6-31.

- Applegate, L.M., & Montealgere, R. (2018). Harvest City: The Intelligent Procurement System Project? Harvard Business School Case, 9, 918-507.