Review Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 6

Innovation and entrepreneurship: Fallacies and disenchantments

Socorro Márquez, Félix O., Complutense University of Madrid

Reyes Ortiz, Giovanni E., Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá, Colombia

Citation Information: Socorro Márquez, Félix O., & Reyes Ortiz, Giovanni E. (2021). Innovation and entrepreneurship: fallacies and disenchantments. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(4), 1-11.

Abstract

Not everything that is pointed out as a result of innovation has an empirical basis in reality, in some cases, the experiences, anecdotes, or initiatives have been exaggerated, adjusted to a particular audience, and even distorted to create an unreal picture of who they were or wanted to be. Those distortions could lead entrepreneurs to the acceptance of certain fallacies as facts and later facing some disenchantment that can affect the perception and understanding of the relationship between entrepreneurship and innovation. Therefore, providing the entrepreneur with documented information that allows him to observe the business activity more objectively and thus adjust his expectations and improve decision-making could be considered as the justification for this study. Using a qualitative methodology, three fallacies and three disenchantments have been documented, considered for their value when projecting entrepreneurship based on the expectations they generate in young entrepreneurs.

Keywords

Innovation, Entrepreneurship, Fallacies, Disenchantments.

Introduction

Once we crossed the threshold of the «information and knowledge age» and linked it with technological development and the challenges it represents the word «innovation» gained strength and began its leading rise in almost all areas of the world knowledge.

In the marketing world there is talk of «Innovate or die», a title that Mario Borghino used when published his book in 2008, and whose content is aimed at explaining how to compete in saturated markets.

For his part, Trías, known for his participation in the book «La Buena Suerte» (The good luck), and «The entrepreneur's black book», alludes to innovation in his 2011 work «Innovate to win», thus joining other authors such as Pecorella, Friedman and Costa, who show innovation as the path that must be followed by anyone who wants to introduce changes and improvements in any field.

And so, as happened with leadership concept, where at first only their three most accepted and well-known styles were spoken (autocratic, democratic and laissez-faire), then fragmented into many more.

Innovation went from being a linear and fixed concept, to become a reason for discussion, redefinition and reclassification to the point of talking about its many variations, as proposed by Tom Kelley in his book «The 10 Faces of Innovation» in 2010 or as proposed by Larry Keeley, Ryan Pikkel, Brian Quinn, and Helen Walters in their book «Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Progress», written in 2013.

However, not everything that is said and pointed out as a result of innovation, or even as the genesis of it, is empirically grounded in reality.

In some cases, the experiences, anecdotes or initiatives have been exaggerated, adjusted to a particular audience and even distorted to create an unreal picture of who they really were or wanted to be.

These deformations of reality ended up in the collective imagination, creating wrong expectations about what, how and what the expected result of an innovation process should be.

When what the entrepreneur expects does not match what he/she can, he/she may experience frustration, discouragement, and dissatisfaction, which could affect his/her ability to plan, set objectives and goals, and make good business decisions.

This exaggerated or distorted reality, related to innovation process, can be understood as part of the fallacies and disenchantments that exist in the entrepreneurial field.

Based on all the aspect aforementioned, this study chase to give a response to the following questions: What fallacies are associated with innovation in the field of entrepreneurship? What disenchantments are related to innovation as part of the entrepreneurship sphere?.

Review of Literature

Innovation

The term innovation has been studied, defined, expanded and complemented by different authors throughout history, however, below; in Table 1 those concepts that provide support to the purpose of this study are listed.

| Table 1 Concepts of Innovation | |

| Author | Innovation Concept |

| Medina & Espinoza, cited by Bustamante (2012) | This “term etymologically innovate comes from the Latin innovare, which means to change or alter things by introducing novelties”, also emphasizing that “in turn, in the common language, innovating means introducing a change”. (idem). |

| García (2012), | Innovation is “the transformation of knowledge into new products and services. It is not an isolated event but the continuous response to changing circumstances is the successful exploitation of ideas”. Or “a new or significantly improved product (good or service), a process, a new marketing method, or a new organizational method in the internal practices of the company, the organization of the workplace or of foreign relations”. |

| Schumpeter (1942), cited by Ángel (2016) | The introduction of new goods and services in the market, the emergence of new methods of production and transportation, the achievement of the opening of a new market, the generation of a new source of supply of raw materials and the change in the organization in its management process. (Ángel, 2016). |

| Dosi (1988), cited by Ángel (2016) | “The search and discovery, experimentation and adoption of new products, new production processes and new organizational forms”. |

| Cooper (1990), cited by Ángel (2016) | a complex system and approaches it from the perspective of the success of product innovation strategies, through what he defines as two independent and parallel processes: a development process and another of evaluation. With this, what Cooper proposes is to analyse the innovation process from a strategic perspective (Ángel, 2016). |

It is important to note that, in addition to definitions, some authors have established categories for innovation, in this sense, Ángel (2016), points out that:

In the different attempts to classify the innovations, located a five-point scale to differentiate the innovations, in: systemic, important, minor, incremental and unregistered, and for their part, used four categories. However, the vast majority of authors have used the categorization which proposes two concepts of innovation: incremental and radical.

Therefore, it can be said that innovation is a set of actions, guidelines and processes that introduce changes, improvements, transformations or alterations in different fields and aspects of various kinds, whether in a product, a service or a combination of these issues.

Innovation According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

According to Aulet (2014), in a video on Innovation, published by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), through the website ocw.mit.edu, on the occasion of their Open Course Ware, given in April 16, 2014, it is explained that, according to Edward Roberts, professor at that institution, innovation comes down to one equation:

Innovation = Invention * Commercialization

The above, in the words of Aulet (2014), suggests that if the invention cannot be commercialized, the innovation does not exist, or that if the commercialization of something is carried out without an invention process having taken place, the innovation does not exist.

So, it can be seen, according to what Aulet (2014), explains, in the video, that invention and commercialization must go hand in hand so that it can be said, with propriety, that it has innovated.

However, the previous concept seems to be more related to commercial and entrepreneurial aspects than under a general and standard vision of the term.

Types and Modalities of Innovation

The 2005 Oslo Manual, in its third edition, explains four types of innovation, which are: product, process, marketing and organization, as indicated by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, also known as OECD (2005).

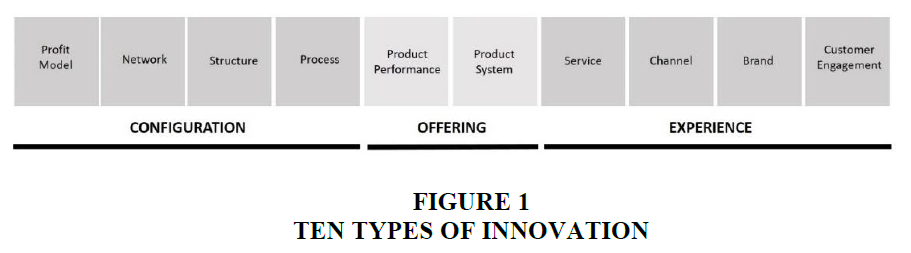

Keeley et al. (2013), expands this classification in the way shown in Figure 1.

The vision of Keeley et al. (2013), encompasses innovation from the business model to creating commitments with customers, obviously, under a commercial vision of the concept that does not stray, but does substantially expand, the conceptualization of the Oslo Manual and it comes close, indirectly, to what Aulet (2014), proposed in his MIT class.

Consequently, the use of innovation, although varied and wide, can be closely related to business and companies, the market and the need to satisfy the needs of either individuals or groups of them.

Since innovation is associated with business, it must be deduced that it will be affected by the way in which the entity or company that develops a particular business is governed, oriented, managed or viewed. Therefore, when it is subject to this, it can be driven or undervalued, nurtured or ignored depending on the expectations, objectives or aspirations of those who exercise power in any of them.

Entrepreneurship

As indicated with innovation, the concept of entrepreneurship has also been explored, expanded and explained by various authors over time, Table 2 lists some of the concepts that fit the scope of this study.

| Table 2 Concepts of Entrepreneurship | |

| Author | Concept of Entrepreneurship |

| Stevenson & Jarillo (1990), cited by Cuervo et al. (2007) | Entrepreneurship is “a process by which individuals-either on their own or within organizations-pursue opportunities”. |

| Carmen & Guerrero (2012), | Entrepreneurship is understood, “such as the refinement of a project that aims to achieve an economic, political or social purpose, among others, and has undeniable characteristics, essentially between them, an allocation of uncertainty and innovation”. |

| Rodriguez (2010), quoted by Gutana & Jiménez (2019) | Entrepreneurship is “derived from the French entrepreneur (pioneer), making mention of a person who has the ability and skill to make an additional effort to achieve a goal definite”. |

However, when entrepreneurship is studied, there are two elements that should be mentioned, these are the figure of the entrepreneur and entrepreneurial behaviour. In this regard, two fundamental sources can be pointed out: Schumpeter and Miller.

Schumpeter (1934), quoted by Gutana & Jiménez (2019), explain that the entrepreneur is “the creator of a new company, an innovator who puts aside the usual way of doing things”.

For Miller (1983), also cited by Cuervo et al. (2007), the entrepreneurial behaviour “is seen as behaviour that manages to combine innovation, risk-taking and proactiveness”.

As can be seen, innovation and entrepreneurship are closely linked. It can be said, then, that it is possible to innovate without undertaking (with no commercial aims), but hardly there will be an entrepreneurship without innovation.

Objectives

The main objective of this study is to provide a critical and objective view of what has been conceptualized and taught in relation to innovation within entrepreneurial field, since, in one way or another, some approaches do not seem to fully conform to the reality experienced at the time of using them or by promoting its application in different scenarios.

Rationale of the Studies

Separating reality from fantasy provides entrepreneurs with an objective and pragmatic vision when setting their goals and initiating a strategic planning process that positions their undertaking in the market and allows it to grow and develop.

When the information received by the entrepreneur lacks real bases but is considered true, it can lead to the generation of wrong expectations that will hinder the achievement of the objectives that arise from them because they do not respond to reality.

For all the above aspects, this study is justified from two points of view. First, from an academic perspective, it documents and describes the fallacies and disenchantments that entrepreneurs can face, giving them the opportunity to know, identify and analyse them.

And second, from a business standpoint, it prepares the entrepreneur to be more objective when setting goals and objectives, carrying out strategic business planning and objectively directing their efforts to the development and implementation of their innovative ideas.

Methodology

Under a qualitative methodology, with an emphasis on documentary research, this study is based on data collected from books, articles, journals and other sources that provided content related and/or linked to the purpose of this research.

Furthermore, from a qualitative methodology with emphasis on documentary research inferential and deductive reasoning has been used.

Boddez et al. (2016), explain that the inferential reasoning can be defined “as a slow and effortful process that starts from premises and returns a conclusion”. Also, the inferential reasoning process “can be represented as a modus tollens argument”, according to Beckers et al. (2005), quoted by Boddez et al.(2016).

For their part Ayalon & Even (2008), deductive reasoning is “unique in that it is the process of inferring conclusions from known information (premises) based on formal logic rules, where conclusions are necessarily derived from the given information and there is no need to validate them by experiments”.

Based on the aforementioned authors and the methodology chosen for this study, it can be said that the steps required to support a documentary investigation have been completed.

Analysis

Fallacies and Disenchantments

Studying fallacies and disappointments is not something new, authors such as Bauerschmidt (2001), have already carried out research on these elements in different disciplines. For example, Bauerschmidt (2001) refers to the disenchantments associated with modernity raised by Max Webber at the end of the 19th century. In relation to these aspects, the following clarifications can be made. See Table 3.

| Table 3 Concepts of Fallacy | |

| Author | Concept of Fallacy |

| Portillo-Fernández (2018) | A deception, a fraud or a lie with which you try to harm someone. The terms sophism (from gr. Σόφισμα) and paralogism (from the gr. παραλογισμός) are usually used as synonyms for the fallacy concept, mentioning an apparent reason or argument with which you want to defend or persuade what is false, or simply false reasoning. |

| Aristotle, cited by Woods (2007) | “As an argument that appears to be a syllogism but is not a syllogism in fact”. |

Peirce, quoted by Trujillo et al. (2007), affirms that “a syllogism is a valid, demonstrative, complete and simply eliminative argument”. To later add that “it is a true argument for all its possibilities, therefore necessary and valid”.

Peirce, quoted by Trujillo et al. (2007), affirms that “a syllogism is a valid, demonstrative, complete and simply eliminative argument”. To later add that “it is a true argument for all its possibilities, therefore necessary and valid”.

For the purposes of this study, it will be understood as a fallacy, that argument that seems to be a syllogism but, in reality, does not have a true or completely true basis.

Now, about the concept of disenchantments, Romero (1998), highlights that Max Weber considered disenchantment (something negative) as one of the main phenomena associated with rationalization.

On the other hand, Yánez (1997), defines disenchantments, as “the loss of magic”, and relates it to “the existence of a mythical thought”, mainly present in modern age.

Therefore, as far as this research is concerned, disenchantment is understood as mythical thought that, faced with the facts, causes an idea to lose its magical or idealized characteristics.

Fallacies and Disenchantments in Innovation

Fallacies and disenchantments come from many and different sources, such as misinterpreted experiences, exaggerated stories, distorted information, or idealized situations that may or may not be related to real events.

These situations promote the appearance of erroneous expectations related to the development of innovation in the entrepreneurial field that can lead to poor decision-making.

Notwithstanding, talking about innovation is very common in classrooms, conferences, specialized journals, and books designed to drive change.

But, beyond what is read, said or heard, there is a reality that defies the idealism that surrounds innovation; therefore, in this case, three fallacies and three disenchantments will be documented from a critical and reflective vision.

Discussion

Fallacies of Innovation

The inspiration fallacy:

According to Romero, & Santaolaya. (2013), the famous painter Picasso said «inspiration exists, but it has to find you working».

If one reflects on this aphorism, it is possible to find that its main contribution is none other than highlighting the impossibility of the human being to determine when and how inspiration will be present. And that's where the fallacy lies.

Although it is not impossible, it is highly unlikely that an innovative idea can be generated in a controlled environment exclusively geared towards it. Imagine a teacher or facilitator asking your students to bring an innovative idea to the next class as the class requires it. Or a manager or director asking his/her employees to do the same for the next company meeting.

Although it is true that efforts can be made to think of something, in response to the pressure that the deadlines impose; it is no less true that such a process cannot be compared to inspiration.

For his part, Barrera (2008), in his interpretation of the work of Manuel Romo (1997), points out that:

Inspiration is the gleaming insight that looms above absolute dedication, effort kept in a specific setting, and a pinch of luck. It is, phenomenologically speaking, the philosophical horizon where the individual glimpses creative illumination, which is by no means exclusive to the scientist or the artist. (Barrera, 2008).

Based on the above, it can be said that, when innovating, it cannot be taken for granted that inspiration will be present immediately and just when we need it. It will simply appear when the conditions are in place and unfortunately there is no way of knowing when it will be.

Therefore, it is a fallacy to suppose that the mere fact of receiving the request to do something innovative, whether in a classroom, a labour board or in an environment subject to regulations; it will impel the individual to feel inspired and challenged for this purpose, since inspiration appears, as Barrera (2008), points out above «absolute dedication», it is, quite simply, fortuitous.

The fallacy of chance:

Creating something for a market can led to the exploration of that something in a market or for a purpose other than the one planned, as happened with 3M's post it.

As Vieda (2011), explains:

The Post-It was an invention of the chemist Dr. Spencer Silver, who worked for the 3M company in 1968 as an Executive Scientist at the Corporate Research Laboratory. His job was to find a high-capacity glue that could be used in airplane construction. However, the result was a high-quality glue but weak enough to glue two sheets together and then peel them off without damaging them. (Vieda, 2011).

But such a discovery cannot be attributed to chance, since it was the consequence of the research, testing and testing of the chemist Silver, but they cannot be framed in the combination of circumstances that cannot be foreseen or avoided.

Something similar can be seen in the case of the Play-Doh!

Velásquez (2014), comments that “many are the brands that are born due to an error or because a new application was given to it. Play-Doh!, it is one of these cases”.

Velásquez (2014), also ensures that:

The mass of Play-Doh! was created by Cleo McVicker (...), its main function was to clean the soot off the walls. When electric heating came to homes, this mass began to become obsolete (…) In search of solutions, Kay Zufall, (…) realized that children were playing with that mass that was used to clean the walls. He immediately went to tell Mcvicker and proposed the idea of colouring it. (…) In 1956 the first Play-Doh! was released.

As in the previous case, this innovative and widely known product did not arise by chance, it was the result of a change of orientation in its use and market.

Therefore, it is a fallacy to suppose that always innovation is a casual event, which occurs unexpectedly, on the contrary, it arises from the exploration of unforeseen scenarios that, in light of an event, are clearly glimpsed, without this modifies the product that has emerged from the innovation, only its application or utility is affected.

The fallacy of the spontaneous generation:

Aristotle is credited with creating the Theory of Spontaneous Generation. According to Romero (2015), Aristotle “was a staunch defender of spontaneous generation, according to which any decomposing substance is capable of generating worms or larvae”.

This concept, typical of biogenesis, has been transferred to the world of business, education and entrepreneurship, adjusting it to its characteristics and conditions.

It can be read in the Diari Digital d’Alcoi, ALCOI23 (2017), a review of Caixa Ontinyent's social work that confirms the previous statement:

The inaugurated space is located in the Georgina Blanes building, in company with the rest of the workshops belonging to the Spontaneous Generation groups that will soon have a new area dedicated to Entrepreneurship. Once the Opening Act of the Academic Course 2017-2018 had ended, the attendees went to the third floor of the Georgina Blanes building where the Spontaneous Generation Design Factory space is located, sponsored by the Caixa Ontinyent Social Work, as a result of the Classroom of Company signed between both entities in 2015.

This initiative is based on the fact that ventures simply arise, as explained by spontaneous generation, thanks to the combination of simple and common elements in the environment.

Although it is true that ideas arise spontaneously, it is no less true that knowledge of the market, its needs, interests, trends and expectations is required to successfully promote an enterprise and develop an innovation.

It is difficult to imagine that an innovative idea arises without having previously been in contact with a lack, a need or an event that caused it, so it is not possible to affirm that its generation is totally spontaneous.

Disenchantments of Innovation

Disenchantments in Relation to Financial Resources

Innovation without resources has the same value as a dream without implementation. One of the best-known cases supporting this aphorism can be found in the life and work of Nikola Tesla. Rodríguez (2017), explains:

Tesla immediately broke the contract they had signed and renounced his rights for the use of their patents for the distribution of alternating current, a gesture that was enormously generous, but this subsequently prevented him from financing the projects that his privileged mind devised.

Although there must undoubtedly be more than one example on the subject, what happened with Tesla summarizes, in essence, the objective of this section: Financial resources are required to carry out the ideas that may arise from the mind of an entrepreneur; the idea in itself is not enough.

Without money it is difficult to materialize an idea, unless it does not require inputs, materials and/or technology to be carried out and, nevertheless, thinking about the use of human resources as the only source to implement it, also limits its duration, effectiveness and impact, so it is difficult, without financing, to materialize an innovation.

Disenchantments in Relation to Timing

The innovation must appear and be marketed at the right time, otherwise, it may be copied or used by third parties without bringing benefits to its promoters.

An example of this can be found in the origin of fax machine, according to Keyes (2018):

In 1843 (…) Alexander Bain applied for and received a British patent for a device consisting of two feathers connected to two pendulums and then connected together by a cable to allow writing on electronically conductive material. (...) in the 1960s (...) Xerox Corporation introduced the first reliable, long-distance fax machine, but it wasn't until Japanese companies became embroiled in the 1970s that the truly modern fax machine arrived to exist.

The fax was invented in 1843 and it took 117 years for it to start using it and then another 10 years for it to be successfully marketed, which adds up to a total of 127 years from its invention to its commercialization. What entrepreneur, company or organization is in a position to wait so long?.

Another example can be seen in the Sony Minidisc, launched in 1992 and which failed to compete with digital devices that emerged a few years later such as the MPManF10 and the iPod.

At the time, audio tapes dominated the market and the use of music CDs was beginning to grow. SONY's proposal was to introduce a disc that was smaller than a tape and a 3.5” floppy disk in a reader similar to its already famous Walkman. However, it failed to capture fans as expected, and with the advent of MP3 in 1995 and the aforementioned devices, the Minidisc technology seemed out of date. It would have been ideal to have it at least about 5 years before its launch.

Therefore, it can be considered a disenchantment to notice that innovation has a specific moment in history: if it is presented before the conditions are in place for its use and commercialization, as it happened with the fax machine, it may take years before its usefulness is found and, if it occurs after a disruptive moment, when its benefits have been outweighed by other innovations, it ends up being displaced and even ignored.

Disenchantments in Relation to Acceptance

Not all innovations are accepted as such, either because they do not have the necessary resources to make them known in the target market or because they have not arisen at the best time, being overcome or simply replaced by others.

An example of the second case, not coming out at the best time was Microsoft's 2010 Mobile Kin:

Oliveira (2010), explains that “the Microsoft Kin were a pair of terminals promoted as 'designed to be social'; devices that combine the functionalities of a mobile phone, together with the main on-line communication services offered by a computer”.

For his part, Pérez (2010), points out that:

The KIN One and KIN Two, two models of cell phones launched in April [2010] by Microsoft with the aim of capturing the young audience through a strong commitment to social networks (...), but the lack of equipment and their outdated designs caused both devices to fail miserably.

This suggests that, even with financial resources, such as those that the Microsoft company may have, if innovation does not arise at the right time, it tends to be ignored, such as, for example, when it was normal for telephones to have keyboards (1995-2005), as noted above.

Then, it can be considered as a disenchantment to notice that not all innovations are accepted for being novel. The diversity in the offer, the substitutes, the similar products, with or without greater added value, can mean the absence of acceptance by the target market, which requires skill and skill to have it.

Conclusions

Innovation is a fundamental part of entrepreneurship. As already mentioned, there can be no entrepreneurship without innovation. This is why, when talking about innovation, it can be found affirmations or approaches that do not necessarily describe the reality of innovation within the entrepreneurship, thereby generating fallacies and disenchantments.

Based on the theoretical aspects discussed in this study, innovation is a change that implies improvements, so all innovations are changes. But not all changes are innovations, that is why it is important to study the relationship between innovation and entrepreneurship.

In the strict sense of Aulet (2014), innovation requires invention and commercialization to be considered as such thing.

Innovation is affected by many factors that can be divided into two main sets. The context aspect, for example, the effective demand of the markets. And the historical development of conditions.

Following these issues, the fallacies concerning of inspiration, casualty and spontaneous generation are understood. And, at the same time, the disenchantments related with financial resources, timing and acceptance are explained as well.

Three fallacies and three disenchantments have been documented, even when there may be more of them being used and/or experienced in the field of entrepreneurship; as a reflection on the importance of the study of the facts, instead of considering as true what is heard, read or observed without contrasting it with reality.

Managerial Implications and Main Contribution of the Study

An entrepreneur must base both her/his business project and her/his plans and expectations on possible, measurable and quantifiable objectives. As part of a general trend, the more objective her/his vision is, the more accurate her/his plans and actions will be. That is why every entrepreneur must know and understand the failures that exist around business and be prepared to face the disenchantments that some experiences may cause. Therefore, the main contribution of this study is none other than providing the entrepreneur with documented information that will allow her/him to observe business activity more objectively and thereby adjust her/his expectations and improve decision-making.

References

- ALCOI23. (2017). ALCOI23.COM. Retrieved from https://www.alcoi23.com/2017/10/29/inaugurado-espacio-generacion-espontanea-design-factory-campus-la-upv-alcoy/

- Ángel, B.E. (2016). El concepto de innovación. Libertelia. Retrieved from http://libertelia.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/El-concepto-de-innovacio%CC%81n.pdf

- Aulet, B. (2014). https://ocw.mit.edu. Retrieved from Lecture 2: What is Innovation: https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/sloan-school-of-management/15-390-new-enterprises-spring-2013/video-tutorials/lecture-2/

- Ayalon, M., & Even, R. (2008). Deductive reasoning: in the eye of the beholder. Educ Stud Math (69), 235–247. doi:10.1007/s10649-008-9136-2

- Barrera, L. (2008). Psicología de la creatividad. CESUN-Universidad, 58-59.

- Bauerschmidt, F.C. (2001). The Politics of Disenchantment. New Blackfriars, 82(965/966), 313-334. Retrieved April 22, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43250594

- Boddez, Y., De Houwer, J., & Beckers, T. (2016). The inferential reasoning theory of causal learning: Towards a multi-process. In M.R. (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Causal Reasoning (pp. 1-37). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bustamante, J.P. (2012). Wiki Oei. Retrieved from http://www.eoi.es/wiki/index.php/Evoluci%C3%B3n_del_concepto_de_Innovaci%C3%B3n_en_Innovaci%C3%B3n_y_creatividad_2

- Carmen, C., & Guerrero, L. (2012). El Emprendimiento y sus Tenciones desde la Política Pública. Cali: Fundación Universitaria Católica Lumen Gentium/.

- Cuervo, Á., Domingo, R., & Roig, S. (2007). Entrepreneurship: Concepts, Theory and Perspective. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-48543-8_1

- García, F. (2012). Conceptos sobre innovación. (F. Garcia González, Producer) Retrieved from acofi.edu.co: http://www.acofi.edu.co/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/DOC_PE_Conceptos_Innovacion.pdf

- Gutana, M.G., & Jiménez , P.S. (2019). El emprendimiento y su evolución como una alternativa laboral en el contexto latinoamericano: una revisión de literatura. Retrieved from http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/:http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/bitstream/123456789/31772/1/EL%20EMPRENDIMIENTO%20Y%20SU%20EVOLUCI%C3%93N%20COMO%20UNA%20ALTERNATIVA%20LABORA.pdf

- Keeley, L., Walters, H., Pikkel, R., & Quinn, B. (2013). Ten Types of Innovation: The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Keyes, B. (2018). https://www.geniolandia.com. Retrieved from https://www.geniolandia.com: https://www.geniolandia.com/13132031/cuando-se-invento-la-maquina-de-fax

- Oliveira, P. (2010). http://www.publico.es. Retrieved from http://www.publico.es: http://www.publico.es/actualidad/microsoft-cancela-produccion-moviles-kin.html

- Pérez, M. (2010). https://vos.lavoz.com.ar. Retrieved from Otro fracaso de Microsoft: Los celulares KIN One y Two serán discontinuados por falta de demanda.: https://vos.lavoz.com.ar/amp/content/otro-fracaso-de-microsoft-2

- Portillo-Fernández, J. (2018). El uso de falacias en la comunicación absurda. Logos: Revista de Lingüística, Filosofía y Literatura, 443-458. doi:10.15443/RL2832

- Rodriguez, D. (2017). Vida de Nikola Tesla. Retrieved from http://www.sciencenov.com: http://www.sciencenov.com/vida-nikola-tesla/

- Romero, R. (2015). Aristóteles: Pionero en el Estudio de la Anatomía Comparada. Int J Morphol. 333-336.

- Romero, & Santaolaya. (2013). Un centro lúdico como refuerzo educativo en período vacacional. ReiDoCrea, 150.Retrieved from http://digibug.ugr.es/bitstream/10481/27755/1/ReiDoCrea-Vol.2-Art.20-Marin-Romero.pdf

- Romero, A. (1998). http://anibalromero.net/. Retrieved from Desencanto del mundo, irracionalidad etica, y creatividad humana en el pensamiento de Max Weber: http://anibalromero.net/Desencanto.del.mundo.irracionalidad.etica.creatividad.humana.en.el.pdf

- Trujillo, A., Fernando, J., & Vallejo , X. (2007). Silogismo teórico, razonamiento práctico y raciocinio retórico-dialéctico. Praxis Filosófica, 79-114.

- Velásquez, C. (2014). Expertosenmarca.com. Retrieved from http://www.expertosenmarca.com/historia-de-marca-play-doh-el-juguete-para-ninos-que-nacio-por-error/

- Vieda, M. (2011). Vieda Manuel. Retrieved from https://manuelvieda.com/blog/la-historia-detras-de-los-post-it/

- Woods, J. (2007). The Concept of Fallacy is Empty. Model-Based Reasoning in Science, Technology, and Medicine: Studies in Computational Intelligence, 69-90. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-71986-1_3

- Yánez, S. (1997). Desencanto y Literatura (elementos para el análisis). Quito: Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar.