Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 1S

Islamic Banking Development in Asian Countries: Under the Republic of Kazakhstan

Serik Kairdenov, Sh. Ualikhanov Kokshetau State University

Anargul Belgibayeva, Sh. Ualikhanov Kokshetau State University

Indira Ashimova, Sh. Ualikhanov Kokshetau State University

Irina Savchenko, Humanitarian-Technical Academy

Keywords

Islamic Banking, Deposit, Shariah, Banking Products, Consumer Value, Service Level.

Abstract

A detailed study of the characteristics of the second-tier banks and the phenomenon of Islamic bank aims to reveal some distinctive features of Islamic banks. These features include traditional, culturological and ethical values, economic attractiveness, which lies in the geo-economic proximity of the post-Soviet states and the Arabian monarchies, religious orientation, on which the entire economy of Islamic countries is based, the importance of principles and regularities of banking operations in view of new trends in international economic development. The purpose it to involve regional groups, transnational corporations and other actors of the world economy with monetary, financial, trade, industrial, and labor relations. The novelty is that this requires finding alternative solutions to pressing problems of the banking sector of the economy of Kazakhstan and other Central Asian countries which was described in the article. The main conclusion of the research on Islamic banks is that the performance of Islamic banks is strongly influenced by the number and volume of deposits, which in turn affects the policy behavior and management of Islamic bank.

Introduction

Social and economic characteristics of a modern state depend, among other things, on the activity of the banking system (Hernandez, 2016). First of all, human welfare in this system depends on subject-object financial relations, i.e. when monetary deposits of some actors become a loan for others. Banks become guarantors of some actors in front of others by relieving depositors from the necessity to investigate the reliability of borrowers. Here the functions of banks are reduced to the accumulation of money, transformation of resources and regulation of money turnover for the purpose of profit, which demonstrates their commercial nature. In the financial market of any state, a large niche is occupied by second-tier banks, which have their own economic requirements to both borrowers and lenders. Thus, as of October 1, 2018, in Kazakhstan, there was 28 second-tier banks, 13 of which had foreign capital, the share of which was 17.1% (Ibrayeva, 2018).

The main objective of the second-tier banks is to make mandatory profits, which are subject to irretrievability risks. Credit risks, liquidity risk, and interest rate risk lead to the loss of monopoly, the traditional advantage of the bank. Loss of monopoly and increased competition led to lower bank margins and increased concentration in the banking sector (Kunhibava, 2014; Uzochukwu, 2021).

Currently, along with traditional or well-known western models of banks, the world is developing a network of Islamic banks, the rapid growth of which is observed in the Gulf and Southeast Asia, with the principles of Islamic banking today is successfully applied not only in Muslim countries but also in the U.S. and Europe (El-Husseini, 2015; Amelia et al., 2021). Some European banks, due to the liquidity crisis in Europe and the U.S., are opening special "Islamic windows" in their structures in parallel with its standard set of services. Such branches of the traditional bank provide services under Shariah rules.

At present, the banking system of Kazakhstan is a dynamically developing sector of the economy of Kazakhstan and its level (about 90% of GDP) is comparable with the indicators of the EU countries. Kazakh banks are actively expanding their operations in Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Ukraine, and other countries by conducting transnational operations from their head offices in Kazakhstan, as well as using purchased banks and their representative offices.

Literature Review

For the purposes of this work, the authors in a literature review compared the scale of activity of Islamic banking and finance capital in six Muslim republics of the former Soviet Union: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. To a greater or lesser extent (depending on the nature of their political and economic system in the post-Soviet period), all of them integrated Islamic institutions into their financial and banking sectors, and the Islamic Bank acted as the primary catalyst of this process (Iqbal & Molyneux, 2016). Islamic banking and finance capital is actively entering the financial services market in those countries where liberal economic reforms are progressing more successfully (Khan 2010; Hendriarto, 2021), primarily in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. But, as will be shown below, in these two states, Islamic banking also faced complex political games typical for rentier countries (Chonga & Liu, 2009; Jawadi et al., 2017). A country is classified in this category if a significant part of its national income comes from exploiting local natural resources, including oil and natural gas. So that Islamic banks and financial institutions can establish themselves in these countries (Aliyu et al., 2017), as, indeed, in other rentier countries, for example, in Turkmenistan or Uzbekistan, the local political elite, it is believed, should be directly involved in the formation of the relevant banking and financial institutions, as well as in the following benefits from their activities (Beck, 2013).

Although the public practice of religion was suppressed in the Soviet Union, Islam (especially Sufism - Islamic mysticism) played an important role in all six republics' history and culture. With the collapse of the USSR, political Islam moved to the forefront of these republics' political life. During the period of modern means of communication, Islamist groups (their vivid example is the Hizb ut-Tahrir movement, an Islamist party that seeks to unite all Muslims of the planet in a single Islamic state, the Caliphate) established closer ties among themselves, became more organized and militant. The situation worries many leaders of the states of the region (Gait & Worthington, 2008). In most cases, the authorities' first reaction is to suppress suspected terrorist or opposition groups (Dali et al., 2013). For example, in Uzbekistan, the country's President, I. Karimov, over and over again unleashed repressions on everything that at least somehow resembled the Islamist movement, without caring about the justification of such measures. However, such violence only turned many people against the government of the republic (Mohamed et al., 2018). Also, the head of state, I. Karimov, has to look for a line of conduct concerning such his neighbors as Tajikistan or Afghanistan, where, due to the existing problems with maintaining the rule of law, groups like the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) or Hizb ut-Tahrir can easily take refuge. In Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Kyrgyzstan, Islam remains a relatively stable factor despite the rise of militant Islamism in the region (Moisseron et al., 2015; Hugar & Manohar, 2018). As for Turkmenistan, at one time, the President of the Republic, S. Niyazov, transformed traditional Islam to such an extent that it turned into something particular, unlike anything else (Nawaz & Haniffa, 2017).

Against the backdrop of the rise of Islam in Central Asia, most countries in the region have begun to welcome the presence of international Islamic financial institutions, notably the Islamic Bank, as they can help the authorities combine the ideas of Islam with socio-economic development (Sole, 2007; Fathi et al., 2017). Islamic banks and financial institutions, in which usury (riba) is unacceptable, have just begun to take root (Noordin et al., 2016; Jaya & Purbadharmaja, 2021). With their help, it is possible to redirect Muslims' energy seeking to integrate Islamic institutions into government systems fully (Safiullah & Shamsuddin, 2018).

In particular, many projects of the Islamic Bank are related to the development of infrastructure (Rahman et al., 2014), that is, roads, telecommunications, airports, canals, and social development (construction, equipment of schools and hospitals).

Material and Methods

One of the most promising tasks is the expansion of cooperation and strengthening trade ties between the Muslim countries of the planet. In pursuing this goal, Islamic bank does not hide its desire to enhance the contacts of the former Soviet republics of the region with the states that are members of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC). The aim is to bring the transitional economies of the Muslim CIS countries (none of them landlocked) closer to the OIC member countries, facilitating trade, investment, and dissemination of best practices by facilitating institution building and capacity development.

The study of efficiency and competitiveness of Islamic banks, in our opinion, should be carried out by an expert method with the use of mathematical methods of generating and taking strategic decisions regarding the level of bank competitiveness. The level of bank competitiveness is an integrated indicator of the level of effective performance of a bank in areas of economic, labor-related, and social activities. When making a management decision on the successful entry of the IDB into the territory of Kazakhstan, it is necessary to take into account the tight competitive environment in the financial services market. Provided that the management is focused on the multilateral analysis of the situation, making extraordinary decisions, and constant creativity, a positive result is possible (Lebedev & Kankovskaya, 1997).

Growing consumer demand for banking services is changing the institutional structure of the financial market in a dynamic way. The variety of elements of the infrastructure of the existing traditional banks such as a mortgage, car loans, and retail divisions providing banking services increases the impact of the competitive environment on the activities of various non-traditional banks (Rosly, 2005; Alharbi, 2015; Ratnasari, 2020). The existence of a free niche of the consumer segment of the Muslim population gives strong competitive advantages for the development of Islamic banks in Russia despite strong competition from the existing banking system of Russia. The banking system is a set of banking institutions functioning on the territory of a given country in interrelation with each other (Vechkanov & Vechkanova, 2003).

In the authors’ opinion, the enhancement of competition in the banking services market is determined by the following factors:

• Increase in the number of competitors in the respective market. It is known that there are about 200 banking institutions operating in Russia;

• Competition is growing on the market provided that the volume of consumer demand for banking services is slowly and gradually growing;

• Insufficient differentiation of banking products also intensifies competition for market share among financial market participants;

• The intensity of banks' strategic behavior when using innovative service and management technologies also leads to stronger competition.

Thus, the timely and constructive behavior of the IDB in the market, with the application of successful economic forecasts, can achieve the expansion of a bank's field of activity, if it focuses on the idle consumer segment of the banking services market.

The analysis of the existing methods of assessing the level of competitiveness of goods and services allowed revealing that the most objective method of assessing the level of competitiveness of banking products is the method developed by Dr. K.R. Nurmagambetov. This method was adapted to the assessment of banking products of Islamic origin. The algorithm for assessing the level of competitiveness of banking products is as follows:

• The definition of the list of experts in the field;

• Ranking the factors of the level of consumer value of the product;

• A competent ranking of the customer service level of a bank;

• The calculation of the level of competitiveness of the banking product;

• Making a strategic decision.

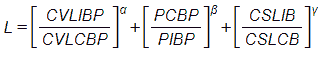

Basic formula 1 for calculating the level of competitiveness of a bank product is as follows (Petukhov & Nurmagambetovm, 2000):

where

L – level;

CVLIBP - consumer value level of the investigated bank’s product;

CVLCBP - consumer value level of the competitor's bank product;

PCBP - price for competitors' banking product;

PIBP - price of the investigated bank’s product;

CSLIB - customer service level of the investigated bank;

CSLCB - customer service level of the competitor bank.

The sum of the exponents of the fractions shall be equal to 1.

To achieve the convenience of calculations according to Formula 1, we offer a tabular method of calculations based on a competent ranking of the consumer properties factors of bank products (see Tables 1 and 2).

| Table 1 Consumer Value Levels of TwoBanks’ Products |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer properties of abank product | Al Hilal (Kazakhstan) | Amal (competitor, Russia) | Relative value | |

| 1 | Availability ofinformation | 5 | 4 | 0,20 |

| 2 | Product'sreputation | 4 | 5 | 0,30 |

| 3 | Risk hedging | 4 | 5 | 0,20 |

| 4 | Efficiency | 5 | 3 | 0,20 |

| 5 | Consultingsupport | 5 | 4 | 0,050 |

| 6 | Liquidity | 4 | 3 | 0,050 |

| 1,00 | ||||

Source: The authors’ research.

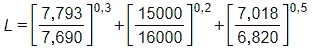

The absolute level value of consumer properties of the investigated bank’s product is as follows:

Consumer value level of the investigated bank’s product= 50,2+40,3+40,2+50,2+50,05+40,05= 7,793;

Consumer value level of the competitor's bank product= 40,2+50,3+50,2+30,2+40,05+30,05= 7,690.

| Table 2 Service Levelsof Two Banks |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors ofCustomer Service Level of a Bank | Al Hilal (Kazakhstan) | Amal(competitor, Russia) | The Relative Value of theFactor | |

| 1 | Theprofessionalism of bank officers | 5 | 4 | 0,5 |

| 2 | Communicationskills of managers | 4 | 4 | 0,3 |

| 3 | Degree of abank manager’s empathy | 3 | 3 | 0,1 |

| 4 | Feedback frombank customers | 5 | 4 | 0,05 |

| 5 | After-salescustomer service by the bank | 4 | 3 | 0,05 |

Source: The authors’ research.

The customer service level of the investigated bank= 50,5+40,3+30,1+50,05+40,05= 7,018;

The customer service level of the competitor bank= 40,5+40,3+30,1+40,05+40,05= 6,820;

The absolute level value of bank product competitiveness across all criteria is as follows:

Thus, the competitiveness of Al Halil's bank product is positive in relation to its competitor's bank product. Financial systems are demonstrating a viable mechanism characterized by reliability and stability, and Islamic finance is taking more and more confident positions in the global financial system.

Demonstrations

The analysis of Islamic finance instruments by country shows that there is no universal standard among the countries participating in the IDB, which does not prevent each country from developing all sectors in its own country through Islamic finance.

Internal factors of an Islamic bank's development determine the level of competitiveness in two main aspects: the quality of management and applicable service standards, and their effectiveness. Experts of Islamic finance emphasize the fact that customers use products of Islamic banks mainly for economic reasons but not for religious reasons. Customers of Islamic banking products are attracted by the factor of efficiency in relation to the regular customers of the bank, which requires a minimum number of service conditions for project financing. The activities of Islamic banks promote international trade and development of globalization processes by providing mudarabah letters of credit when the bank imports the declared goods and resells given goods to the client of the bank, thus taking more risk on itself and protecting the client of the bank from risks.

Research Results

The ultimate goal of a consumer of banking products is the effectiveness of the financial transaction and the efficiency of implemented projects. The risk insurance system in the Islamic banking system is basic and has a huge potential for risk insurance instruments for a client and bank itself (Kunhibava, 2014). There are three main groups of activities of an Islamic bank: receiving deposits from customers of the bank, financing projects, and other banking services. The principles of Shariah are applied and interpreted by countries in accordance with domestic laws adopted by the government. The structure of banking products of Iran is a clear example of the application of Islamic banking instruments (Table 3) (Ibadov & Shmyreva, 2013).

| Table 3 Structure of Banking Products |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| # | Shariah Principles | Scope of Application | Type of Activity |

| 1 | Hire purchase | ||

| 2 | Civil partnership | Material production | Industry |

| 3 | Legal partnership | Agriculture | |

| 4 | Installment plan | Mining and oil industry | |

| 5 | Forward | ||

| 6 | Direct investment | ||

| 7 | Qardh-ul Hasan | ||

| 8 | Joala | ||

| 9 | Mozarima | ||

| 10 | Makasat | ||

| 11 | Mudarabah | ||

| 12 | Civil partnership | Trade | Import |

| 13 | Legal partnership | Export | |

| 14 | Joala | Domestic trade | |

| 15 | Civil partnership | ||

| 16 | Legal partnership | Services | |

| 17 | Hire purchase | ||

| 18 | Installment sales | ||

| 19 | Joala | ||

Source: Ibadov & Shmyreva (2013).

Civil partnership, installment sales, Qardh-ul Hasan, joala, and direct investment are used in the field of construction and repair. An important factor is the fact that financing for the industrial sector has increased, even though all eight countries analyzed are agrarian. The focus on a particular sector or industry in Islamic finance depends on external and internal factors of bank development (Gulf Finance House, 2018).

External development factors for Islamic banks have four orientations: rules of the Central Bank, economic situation, competition, and a bank's reputation. Pakistan is also a major player in the Islamic banking market and relies on the circulars of the State Bank of Pakistan, which contain the principles of project finance, where the responsibility for losses should be borne by the financing entities (Wilson, 2015).

The complementary principle of Shariah in the form of bai salam is practiced by Bangladesh but the other principles are fully similar to those of Malaysia. The authors provide a comparative table for the main countries in Islamic banking from the perspective of Shariah principles (Table 4) (Kairdenov, 2019).

| Table 4 Comparison Of ShariahPrinciples By Country |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ShariahPrinciple | Malaysia | Bahrain | Bangladesh | Indonesia | Kuwait | Turkey | UAE | Jordan | ||

| 1 | Musharakah | - | + | + | + | - | - | + | + | 5 |

| 2 | Mudarabah | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | + | 5 |

| 3 | Murabahah | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | + | 6 |

| 4 | Bai bithaman | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| 5 | Ijarah | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | + | 4 |

| 6 | Qardh-ul Hasan | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | 2 |

| 7 | Istisna | + | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | 4 |

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 6 | |||

Source: The authors’ research.

Islamic banks stimulate international trade with the use of three methods: wakalah method, musharakah method, and murabahah method. The choice of method is dictated by the needs of the bank client (Table 5) (Kairdenov, 2019).

| Table 5 Comparison of Shariah Principles By Country |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Contract | Role of the Bank | The Interest of the Bank | |

| 1 | Wakalah | Agent and representative of the customer | Payment for services |

| 2 | Musharakah | Partner of the customer with the share of financing | Service and management fees. Share of profits |

| 3 | Murabahah | Islamic bank as an entrepreneur | Fixed payment and management costs. Fees. Commissions |

Source: Kairdenov (2019).

Discussion

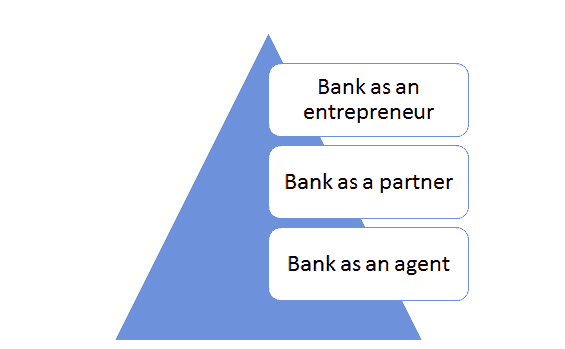

Thus, the economic behavior of an Islamic bank in international transactions has an evolutionary character from the behavior of a simple agent of the bank's customer to an active entrepreneur creating the fund-forming industries of a country (Figure 1).

The structure of international transaction services in all IDB countries is different but letters of credit are provided by all IDB members, which in our opinion is a powerful tool to promote international trade between all countries (Nursyansiah, 2018). Only Malaysia provides all kinds of international trade services (Rudnyckyj, 2013; Islamic Bank Malaysia, 2018; Quan et al., 2019).

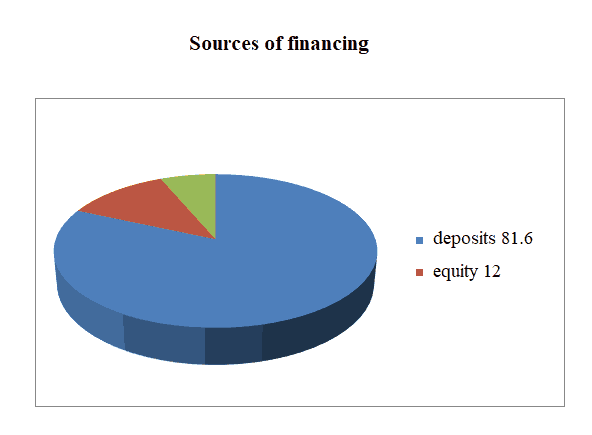

As we know, there are three sources of Islamic banks: deposits, equity, and other liabilities. Equity includes paid-in capital, various reserves, and retained earnings. In the study of the best pre-crisis year, the structure of sources of financing of the countries participating in the IDB was as follows (Table 6) (Kairdenov, 2019).

| Table 6 Sources of Financing ofIslamic Banks By Idb Member Countries |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDB member country | Holdings | Equity | Other liabilities | Total | |

| 1 | Malaysia | 88,4 | 5,6 | 6,0 | 100 |

| 2 | Bahrain | 72,3 | 20,5 | 7,2 | 100 |

| 3 | Bangladesh | 86,9 | 6,2 | 6,9 | 100 |

| 4 | Indonesia | 87,0 | 8,0 | 5,0 | 100 |

| 5 | Kuwait | 74,4 | 16,0 | 9,06 | 100 |

| 6 | Turkey | 81,2 | 14,5 | 4,3 | 100 |

| 7 | UAE | 77,6 | 12,7 | 9,7 | 100 |

| 8 | Jordan | 84,8 | 12,5 | 3,1 | 100 |

| Mean value | 81,6 | 12,0 | 6,4 | 100 | |

Source: Kairdenov (2019).

An analysis of the sources of financing of Islamic banks shows that the focus is not on equity capital but on deposits of investors (81.2 percent of all sources of financing).

A clear comparison chart of the sources of financing of the IDB is provided in Figure 2 (Petrov & Zaripov, 2002).

The acceleration of the replenishment of Islamic banks' deposits is stimulated by the implementation of the policy of powerful social programs of Islamic banks in the following areas: educational aid, humanitarian aid, charitable assistance (Faisal Islamic Bank of Egypt, 2018). Thus, the Bank of Bangladesh with the help of the Islami Bank Foundation enhances social activities related to the following programs: income generation, health, education, dakwah (religious enlightenment), and human resources (Wilson, 2015). Under the social program, six medical facilities, service centers, and five educational institutions have been built. The purpose of this fund is to improve the quality of life of society as a whole. In the same vein, the Social Investment Bank of Bangladesh has been successfully operating since 1995 and has established a waqf money certificate. Islamic banks strive to make available social savings funds, the sources of which are the bank's annual profits (Wilson, 2015). In this way, Islamic banks enable transparent mobilization and fair distribution.

Conclusions and Further Research

The main conclusion of the research on Islamic banks is that the performance of Islamic banks is strongly influenced by the number and volume of deposits, which in turn affects the policy behavior and management of an Islamic bank.

Among the banks in Kazakhstan, a special place is occupied by the Islamic Development Bank, which makes alternative proposals to provide financial support to Kazakhs. It is known that Islamic financial companies differ significantly from traditional ones, primarily due to the fact that they are based on transactions with real assets and changes in their market value.

Islamic banks are part of the credit system of the home countries and are subject to state regulation (Roy, 1991; Wilson, 2015). The role of controlling and regulating agency is performed by the Central Bank, which coordinates activities of Islamic banks through laws and regulations. Islamic banks are limited liability companies. Despite the fact that the modern idea of an Islamic bank as an independent financial institution designed to meet the needs of customers and ensure the growth of shareholder income, the most distinctive feature is its confessional basis, which influences the mechanisms of doing business (Hassan & Bashir, 2005). Therefore, the laws and canons of the Islamic religion are a kind of spiritual and ethical prerequisites for the development of such a banking system.

The creation of Islamic Development Bank implies a big moral-ethical and humane attitude to people and society because when performing all traditional banking operations such as deposits, credits, letters of credit, accounting and record-keeping of bills, other settlement, and payment operations, they invest funds in the industry, agricultural sector, credit trade, service sector, and finance social projects. All this happens according to Shariah laws serving as a deterrent of aspirations of traditional banks to save and raise interest rates quite justified by time and financial crisis (Lodhi, Kalim & Iqbal, 2005; Muto, AlMaghrebi & Turkistani, 2015). The main advantage of Islamic banking is, in our opinion, the ethical and philosophical basis of Islamic banking, which gives the consumer of Islamic banking products additional risk insurance factors to finance technology projects.

Acknowledgement

The authors of the article express their deep gratitude to the Kokshetau State University named after Sh. Ualikhanov and the Faculty of Economics of the L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University for supporting this research.

Authors Contribution

Writing – original draft: Serik Kairdenov.

Writing – review and editing: Serik Kairdenov, Anargul Belgibayeva.

Data curation: Serik Kairdenov, Anargul Belgibayeva.

Formal analysis: Serik Kairdenov, Anargul Belgibayeva, Irina Savchenko.

Investigation: Serik Kairdenov, Anargul Belgibayeva.

Methodology: Serik Kairdenov, Indira Ashimova.

Visualization: Serik Kairdenov, Anargul Belgibayeva.

Project administration: Serik Kairdenov, Anargul Belgibayeva.

Supervision: Serik Kairdenov, Anargul Belgibayeva, Irina Savchenko.

Validation: Serik Kairdenov, Irina Savchenko, Indira Ashimova.

References

- Alharbi, A. (2015). Development of the islamic banking system. Journal of Islamic Banking and Finance, 3(1), 12-25.

- Aliyu, S., Hassan, M.K., Yusof, M.R., & Naiimi, N. (2017). Islamic banking sustainability: A review of literature and directions for future research. Emerging Markets Finace and Trade, 53 (2), 440–470.

- Amelia, D.F., Adam, M., Isnurhadi, I., & Widiyanti, M. (2021). Market performance and corporate governance in banking sector Indonesia stock exchange. International Journal of Business, Economics & Management, 4(1), 1-7.

- Beck, T., Kunt, D.A., & Merrouche, O. (2013). Islamic vs. conventional banking: Business model, efficiency and stability. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37 (2), 433–447.

- Chonga, B.S., & Liu, M. (2009). Islamic banking: Interest free or interest based? Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 17(1), 125-144.

- Dali, N., Yousafzai, S., & Hamid, H. (2013). The development of islamic banking & finance. Underpinning theory affecting islamic banking consumers post purchase behavior. On ASEAN Economics Development 1–15.

- El-Husseini, A. (2015). Internationalization of islamic banks. In Asutay M. & Turkistani A. (Eds.). Islamic Finance: Political Economy, Values and Innovation, 1, 21-46.

- Faisal Islamic Bank of Egypt. (2018).

- Fathi, W.N.I.W.M., Ghani, E.K., Said, J., & Puspitasari, E. (2017). Potential employee fraud scape in Islamic banks: the fraud triangle perspective, GJAT, 7(2), 79-92.

- Gait, A., & Worthington, A. (2008). An empirical survey of individual consumer, business firm and financial institution attitudes towards Islamic methods of finance. International Journal of Social Economics 35 (11), 783–808

- Gulf Finance House. 2018.

- Hassan, M., & Bashir, A. (2005). Determinants of islamic banking profitability. In Iqbal, M. and Wilson, R. (Eds.). Islamic Perspectives on Wealth Creation, 118-141. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hendriarto, P. (2021). Relevance on islamic principle law with application at the field: Review of islamic banking publication in Indonesia. International Journal of Business, Economics & Management, 4(1), 47-53.

- Hugar, S., & Manohar, R.K. (2018). Maturity pattern of assets and liabilities: A case study of Canara Bank. International Journal of Business, Economics & Management, 1(1), 53-63.

- Ibadov, E.S., & Shmyreva, A.I. (2013). Some aspects of the activities of Islamic banks. Ideas and Ideals, 3, 73-77.

- Ibrayeva, A. (2018). Ranking of Kazakh banks with foreign capital.

- Iqbal, M., & Molyneux, P. (2016). Thirty Years of Islamic Banking: History, Performance and Prospects. Springer: NY, New York.

- Islamic Bank Malaysia. (2018).

- Jawadi, F. (2017). Does islamic banking performance vary across regions? A new puzzle. Applied Economics Letters, 28(8), 567-570.

- Jaya, I.G.N.A.A., & Purbadharmaja, I.B.P. (2021). The role of technology in improving financial inclusivity of banking institution: literature research with Indonesian case. International Journal of Business, Economics & Management, 4(1), 35-46.

- Kairdenov, S.S. (2019). Improving the development management of islamic banking institutions. Institute of economics and demography under the academy of sciences of the republic of Tajikistan.

- Khan, F. (2010). How ‘Islamic’ is Islamic Banking? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76(3), 805-820.

- Kunhibava, S. (2014). Risk management and islamic forward contracts. In Ahmed, H., Asutay, M., and Wilson R. (Eds.). Islamic Banking and Financial Crisis: Reputation, Stability and Risks 136-148. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Lebedev, O.T., & Kankovskaya, A.R. (1997). Fundamentals of Management. Moscow: MiM.

- Lodhi, S., Kalim, R., & Iqbal, M. (2005). Strategic directions for developing an islamic banking system (with Comments). The Pakistan Development Review, 44 (4), 1003-1020.

- Mohamed, M., Said, T., & Umachandran, K. (2018). Prospecting the islamic generations through bediuzzaman said nursi’s vision. International Journal of Economics, Business, and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 1–9.

- Moisseron, J., Recherche, I.De, & Ird, D. (2015). Islamic finance: A review of the Literature. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 14(5), 745–762.

- Muto, K., AlMaghrebi, N., & Turkistani, A. (2015). Understanding the values and attitudes in islamic finance and banking. In Turkistani A. & Asutay M. (Eds.), Islamic Finance: Political Economy, Values and Innovation 1, 253-280.

- Nawaz, T., & Haniffa, R.M. (2017). Determinants of financial performance of Islamic banks: An intellectual capital perspective. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research, 8 (2), 130–142.

- Noordin, F., Kadir, A., Erne, O., & Kassim, F.S. (2016). Proceedings of the 2nd Advances in Business Research International Conference, 389.

- Nursyansiah, T. (2018). Macroeconomic determinants of islamic banking financing. Islamic Finance and Business Review, 11(2).

- Petrov, A.V., & Zaripov, I.A. (2002). The religious foundation of Islamic banks. Model and concept of Islamic banks. Money and credit, (3rd edition). Moscow: KNEU.

- Petukhov, R.M., & Nurmagambetov, K.R. (2000). Market regulation of production in the agricultural sector. Astana.

- Qatar International Islamic Bank. (2018). Quan, L.J, Ramasamy, S., Rasiah,D., Yen, Y.Y., and Pillay, Sh.D. 2019. Determinants of Islamic Banking Performance: an Empirical Study in Malaysia (2007 To 2016). Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 7(6): 380-401.

- Rahman, R.A., Alsmady, A., Ibrahim, Z., & Muhammad, A.D. (2014). Risk management practices in islamic, 30(5), 1295–1304.

- Ratnasari, R.H. (2020). Understanding the Islamic banking system in indonesian modern economics practices.

- International Journal of Business, Economics & Management, 3(1), 212-218.

- Rosly, S.A. (2005). Critical issues on islamic banking and financial markets. Bloomington: AuthorHouse. ISBN 1420837370.

- Roy, D. (1991). Islamic banking. Middle Eastern Studies, 27(3), 427-456.

- Rudnyckyj, D. (2013). From wall street to ‘halal’ street: Malaysia and the Globalization of Islamic Finance. The Journal of Asian Studies, 72(4), 831-848.

- Safiullah, M., & Shamsuddin, A. (2018). Risk in islamic banking and corporate governance. Basin Finance Journal, 47, 129–149.

- Sole, J. (2007). Introducing islamic banks into conventional banking systems. International Monetary Fund, 43(7), 1–28.

- Uzochukwu, O. (2021). Direct selling strategies and customers loyalty in the Nigerian deposit money banks. International Journal of Business, Economics & Management, 4(1), 116-129.

- Hernandez, V.J.G. (2016). The question of changing the concept, role and functions of state. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 4(1), 08-19.

- Vechkanov, G.S., & Vechkanova, G.R. (2003). Macroeconomics. Saint Petersburg: Piter.

- Wilson, R. (2015). Banking regulation, monetary policy and Islamic finance. In Islam and Economic Policy: An Introduction, 77-92. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.