Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 2

Researching Resource Approaches in Social Enterprises

Dr Saurabh, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University

Rohit Bharadwaj, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University

Dr Manoj Pandey, Amity University Madhya Pradesh

Dr Devendra Kumar Pandey, Amity University Madhya Pradesh

Citation Information: Dr Saurabh., Bharadwaj R., Dr Pandey M., & Dr Pandey DK. (2021). Researching resource approaches in social enterprises. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25(7), 1-20.

Abstract

The social enterprises (SEs) often face the challenge of generating and managing their tangible and intangible resources at different stages of their venture. From the startup to scaling the operations or diversifying of the operations, they have to match their mission with their resources. The paper investigates the importance of significant resource approaches at different venture stages of social enterprises (SEs). It is based on a study that follows an alternate template strategy to examine different theoretical perspectives with respect to entrepreneurial actions involved in four different cases of SEs based in India. With the help of cases of four different SEs, the study emphasizes the significance of different resource approaches at their various venture stages. The study presents novel insights on the basis of comparison of different resource approaches. It provides a conceptual contribution to the dimension of resourcing strategies in social entrepreneurship (SE) literature. This paper will be useful for the scholars as well as practitioners who are looking forward to understand the role of different resource approaches for amassing, mobilizing and reconfiguring resources in SEs.

Keywords

Resource Approaches, Resource Combination, Resource Mobilization, Resource Reconfiguration, Social Enterprises, Social Entrepreneurship.

Introduction

The primary goal of SEs is their social mission and to serve this, they need to put together all available resources in the best possible manner as well as develop strategies for having access to external resources (Bacq & Eddleston, 2018; Combs, Ketchen Jr, & Short, 2011; Miller & Wesley, 2010). SEs operate for social transformation and social value creation. This makes them work in environments where acquiring resources at reasonable costs is a difficult chore (Zahra & Wright, 2016) and challenging to match the scarcity (Jaywarna & Jones, 2017; Peredo & McLean, 2006). The major reason for this problem is the resource constraint that obstructs their socially innovative approaches. Furthermore, SEs have to deal with resource constraints because their primary mission is not economic-oriented and effective resource approaches are critical to SEs (Sinthupundaja & Kohda, 2019). Many SE researchers have conducted studies in context of resource approaches such as bricolage, effectuation, causation and socially oriented bootstrapping (Desa & Basu, 2013; Janssen, Fayolle, & Wuilaume, 2018; Jaywarna & Jones, 2017; Weerakoon, Gales, & McMurray, 2019). These studies were focused upon the applicability of approaches in context of SE. However, there is a need to examine the behavior of these resource approaches in context of social entrepreneurial actions and investigate how it is evident in development of social ventures.

The literature in SE lacks of a uniform model of resource theories to highlight: a) which resource approach shall be considered for resource-access and amassing resources, and b) which resource approach is useful for resource combination and resource reconfiguration. It can be argued that no single resource approach can exclusively answer the problem of resource-constraint at each venture stage of a social enterprise. Thus, it becomes obvious to say that there are various resource approaches that have their specific significance in solving problems related to resource acquisition and resource deployment problems, and acting upon the entrepreneurial process in SE. The study highlights resource mobilization approaches like – bricolage, effectuation, causation, improvisation, optimization and bootstrapping for addressing the problem of resource acquisition and resource utilization in the context of SE.

Building upon the case of select SEs, the paper investigates the resource approaches that specifically fit best for resource acquisition, combination and resource reconfiguration, respectively, in a social enterprise. The paper concludes with propositions and critical insights contributing to the theory of resourcing strategies in social entrepreneurship theory and practice.

Theoretical Underpinnings with respect to Resource Approaches

The section discusses the various resource approaches and based on which sets up a ground for a establishing the research questions. Some of the resource approaches in the literature have been identified as:

Bricolage

Introduced by Levi-Strauss (Hatton, 1989), bricolage is stimulated by the scarcity of resources and is dynamically engaged with solving problems through combination of available resources (Baker & Nelson, 2005). It means ‘doing things’ with ‘whatever at hand’(Baker & Nelson, 2005). The resources-constrained environment is the catalyst for bricolage (Janssen et al., 2018) as it enables social entrepreneurs to solve social problems by combining available resources even when they are of marginal use for others (Baker, Miner, & Eesley, 2003; Baker & Nelson, 2005). Bricolage is a set of four capabilities: a) capability to address scarcity of resources; b) managing with available resources; c) devising recombination of resources; d) managing relations with partners (Witell et al., 2017).

Di Domenico, Haugh, and Tracey (2010) expanded the construct of bricolage for social enterprises and redefined it as a set of six capabilities: a) managing with available resources, b) acting against the constraints of limitations, c) improvisation, d) social value creation, e) Networking with partners and relation with stakeholders, and f) influence of critical factors. . Bricolage capabilities can facilitate organizations to identify and meet new opportunities (Baker & Nelson, 2005) with the readily available resources. Thus, bricolage in context of social entrepreneurship can defined as the phenomenon of providing innovative solutions to social problems, by managing with available resources, that commercial organizations fail to meet in a satisfactory manner. The problem-solving approach of social entrepreneurs, described by continuous innovation fits perfectly with the bricolage approach (Nicholls, 2010).

Effectuation

Effectuation approach can be an answer for entrepreneurial activities facing problems in environments that are uncertain and non-linear and where there is not much information for entrepreneurs to easily recognize, evaluate and exploit opportunities (Sarasvathy, 2001). The explanatory factors for effectuation are: a) given set of means and b) selection of possible effects that can be brought with given set of means. Effectuation process take a set of means as given and concentrate on choosing between potential effects that may be created there with set of means (Sarasvathy, 2001). The primary elements that form the rationalization of effectuation logic in entrepreneurship are: a) beginning with means instead of establishing end goals; b) considering affordable loss rather than expected return for evaluating options; c) leveraging relationships in place of competitive analysis for evaluating relationship with external partners; and d) capitalizing and not skipping possibilities (Sarasvathy, 2009). The effectuation process enables entrepreneurs to engage in activities and let on goals to emerge and alter, as they exploit the means under their control while employing in an ongoing process of exploration to find out options for what they will do (Fisher, 2012).

Effectuation processes fits suitably for exploiting contingencies (Sarasvathy, 2001) with expertise and a logic approach. Fisher (2012), proposed four factors of the items related to effectuation construct - a) experimentation, b) affordable loss, c) flexibility, and d) precommitments. Effectuation, in context of social entrepreneurship means the process that involves the collection of choices and agreements that social entrepreneurs make as they exploit skills, knowledge and networks to develop socially concerned ideas (Corner & Ho, 2010). Thus, effectuation helps social entrepreneurs to recognize opportunities and provide choices to exploit those opportunities with skills, knowledge and network management.

Causation

The adoption of causation logic in entrepreneurial context comes from the roots of decision theory (Simon, 1959) which assumes that the fundamental beliefs of decision makers regarding future processes can be deduced by analyzing the forms of heuristics and logical approaches they use to make decision regarding that phenomenon (Sarasvathy, 2001). In a causation process, an entrepreneur chooses an already determined goal and then decides on between means to achieve that goal (Sarasvathy, 2001). It starts with the recognition of opportunities, their evaluation to make goals and plans to exploit those opportunities proceeded by the amassing of resources for developing and serving the solution. The explanatory factors for causation process are goals that are given and entrepreneur chooses between means to achieve those goals by: a) starting with ends, b) investigating and analyzing expected return, c) performing competitive analysis, d) directing future (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2009). The factors involved in the rationale of the causation entrepreneurial process include the recognition and evaluation of opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2003), the establishment of goals to exploit recognized opportunities and the analysis of alternative means to achieve goals whilst accounting for environmental conditions that constrain the means (Sarasvathy, 2001, 2009). Therefore, it can be argued that causation process may help the social enterprises to identify the potential beneficiaries (Nelson & Lima, 2020).

Improvisation

Improvisation is a process which involves combination of intuition, creativity and problem solving (Leybourne & Sadler-Smith, 2006; Witell et al., 2017) to give an original composition based on knowledge and past experience (Duymedjian & Rüling, 2010). Improvisation can be defined as the process of composing and executing set of actions to address a problem while comparing it to previous problems and choosing an antecedent or referent based on past experience and routines (Hmieleski & Corbett, 2003). A referent or antecedent is an action based on the past experience and routines to address the present problem or situation. The feasibility of referent is then evaluated by the entrepreneur to confirm whether it will bring in the desired success or it needs to be improvised or a whole new course of action needs to be defined (Hmieleski & Corbett, 2003). The commonly applied referents could be cognitive heuristics and biases. The whole phenomenon of improvisation takes place extemporaneously such that the entrepreneur is evaluating probabilities and formulating set of actions at the same time towards deriving the solution (Hmieleski & Corbett, 2003). Further, Hmieleski and Corbett (2003) proffers the explanatory variables for improvisation such as: (i) set of actions to address the problem, (ii) comparing the present problem situation to previous problems, and (iii) choosing a referent based on past routines and knowledge.

Optimization

An optimization process involves attaining high quality and standard resources that have demonstrated capabilities for the specific application for which the resource is conceived (Desa & Basu, 2013; Garud & Karnøe, 2003). The acquiring of high quality and standard resources endow the means for firms to augment the functional and organizing efficiencies and recognize desired goals (Shane & Venkataraman, 2003). The optimization approach enable organizations to have a clear picture of the goals they want to achieve and know about the quality of the resources required to accomplish these goals (Desa & Basu, 2013). It can be argued that an optimization process enables the social enterprises to acquire standardized, ready-to-use resources and human capital, for delivering socially innovative products/services to uplift disadvantageous human culture. The capability of social enterprises to optimize resource mobilization facilitates their social mission and increase social value creation.

Social Bootstrapping Behavior

Bootstrapping approach has recently received scholarly consideration as a resource acquisition strategy for small ventures (Ozdemir, Moran, Zhong, & Bliemel, 2016) and SEs (Jaywarna & Jones, 2017). Bootstrapping is a significant organizational capability that impacts how organizations react to their resource requirements in efficient and economic manner (Jaywarna & Jones, 2017). Bootstrapping practices like procuring used equipment, renting and postponing to free up working capital has been discussed by many authors like (Churchill & Thorne, 1989; Jones & Jayawarna, 2010; Rutherford, 2015). Bootstrapping is thought to be an innovative, originative and stringy approach that balances shortage of resources for organizations in their early stage of novel and moderately self-sustainable development (Jones & Jayawarna, 2010; Winborg & Landström, 2001). Jaywarna and Jones (2017), also argue that bootstrapping practices in social entrepreneurship not only helps to access resources but also endows with mechanism for creating social value. The three aggregated dimensions of bootstrapping contributing to resource access and mobilization in social entrepreneurship have been identified as: a) creating resource communities (resource pooling and resource exchanges) b) Persuasion to co-opt underutilized resources (Social appeals and scavenging for free resources) c) Building legitimacy (showcasing credibility, tailored imaging, and third party affiliations) (Jones & Jayawarna, 2010). These aggregated dimensions form the major domains of social bootstrapping behavior.

Methodology

The study is based on an alternate template strategy (Langley, 1999). The strategy was popularized by (Zelikow & Allison, 1999). The alternate template approach is useful for looking into if and how dissimilar theoretical perspectives explain a complex process. It gives an alternative explanation of a similar situation using distinctive theoretical viewpoints and assumptions- thus highlighting elements of every point of view that fit with the data. The “differences among the different interpretations can reflect the contributions and limitations” of each theoretical perspective (Fisher, 2012; Langley, 1999). There are two notions of applying the alternate template strategy. The first involves the development of the hypotheses based on theoretical viewpoints, followed by the hypotheses testing revealing the contributory theoretical perspective that significantly explains the data. The second notion of applying alternate template strategy is using different theoretical perspectives to interpret what is known about a specific condition. The different interpretations are more like alternate complementary readings that focus on different variables and highlights different types of dynamics (Langley, 1999). In the current study, the second notion of alternate template strategy has been applied and details relevant to each step in the research process are explained as follows.

The literature regarding the resource approaches discusses the resource approaches and their appropriateness. It motivates to set up an understanding of they fit in in that enabling SEs to recognize opportunities. Further how they can be explained for their appropriateness for resource acquisition in the early stages and reconfigure and redeploy their resources in dynamic environments for SEs. The next section of this study discusses the behaviors of various resource approaches, and action and decisions of social entrepreneurs in the context of these resource theories. The fit of the actions and behaviors of social enterprises with the resource approaches are analyzed in tables 1-7.

| Table 1 Description of Select Social Enterprises | ||||

| Selco | Conserve India | Rangsutra Crafts India | Ivillage | |

| Founder(s) | Dr. Harish Hande & Mr. Neville Williams (Co-founder) | Anita Ahuja & Shalabh Ahuja | Sumita Ghose | Arya Mahajan |

| Year founded | 1995 | 1998 | 2006 | 2014 |

| Type of Social Enterprise | For Profit | NGO | Hybrid | For-Profit |

| Headquarter | Bangalore | Delhi | Bikaner | New Delhi |

| Social mission/purpose | To deliver sustainable energy solutions that improves quality of life and socio-economic development for the poor. | To empower the disadvantaged people and clean the environment through high fashion. | To empower and develop sustainable livelihoods for rural artisans. | To establish and grow a socially responsible enterprise that offers high quality products and services and contributes to the general upliftment of society, specifically by generating employment for rural women and empowering them through social and financial independence. |

| Key Products/Services | Selco offers a wide range of solar products under the category of a) Solar home lightings b) Solar inverter systems c) Solar water heaters d) DC Home appliances like Butter churners, Grinders. | Conserve India converts waste material into fashionable products like wallet, belt. | The organization manufactures clothes and furniture for houses. These products are made by the rural artisans. Hence, valuing the traditional handicraft and empowering the rural artisans. | The social venture offers a variety of traditional Indian handcrafts designs made by rural artisans (specifically rural women) |

| Target Social problem and solution | SELCO provides sustainable energy solutions and services to under-served households and businesses. It aims to empower its customer by providing a complete package of product, service and consumer financing through Grameen banks, cooperative societies, commercial banks and micro-finance institutions. | Conserve India is providing solution to the mountain of waste in India as well as helping poor rag pickers to earn money for their better life | Rangsutra is enabling rural artisans and craftsmen towards Sustainable livelihoods. The venture is providing them the opportunity of market places for their crafts and designs. | The women of Anupshahr (a small town in UP, India) are not allowed to work and are expected to handle household chores. Additionally, educating girls is seen as a waste of money in Anupshahr. Ivillage is providing education to women of Anupshahr as well as employing them while giving them an opportunity to make the reach of their handcrafts more wide and far |

| Number of Beneficiaries | Around 200000 people till June 2019 | Conserve India has benefited around 1,00,000 rag pickers till may 2019 | Rangsutra has benefited around 3,000 artisans by providing them the opportunity to earn money from their respective crafts | IVillage has helped over 150 rural women in Uttar Pradesh become self-sufficient and self-dependent |

| Data used | Financial reports, Media articles, Press releases, Web interviews | Annual reports, Press releases, Media articles, Web interviews | Website, Media Articles, Press Releases, Annual Reports, Web-interviews. | Newspaper articles, Press releases, Media articles, Web interviews |

| Table 2 Bricolage Approach in Select Social Enterprises | ||||

| Bricolage | Selco | Conserve India | Rangsutra | Ivillage |

| Making do (Bricolage definition)- Actually attempted to solve the problem instead of inquiring whether a solution is possible | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Combination of resources- used available resources for seeking solutions rather than seeking resources from outside |

x | ** | x | * |

| Reuse of resources- reused resources for reason supplementary than that for which they were acquired |

x | ** | ? | x |

| People involvement- involved beneficiaries, customers or suppliers in developing social solutions |

** | ** | ** | ** |

| Minimal-value resources- used ignored and discarded resources/materials for creating new social solutions |

x | ** | * | * |

| Table 3 Effectuation Approach in Select Social Enterprises | ||||

| Effectuation | Selco | Conserve India | Rangsutra | Ivillage |

| Flexibility- Took action for unplanned opportunities as they emerged |

** | ** | * | * |

| Met the opportunities with available resources | x | ** | ** | * |

| Experimentation- Gathered information via experimental and iterative learning techniques to meet the aroused opportunities |

* | ** | * | x |

| Experimented with different alternatives and ways to provide/deliver the social solution(s). | * | * | x | * |

| changed the product/service as per the need and development of social venture | * | ** | x | ** |

| Pre-commitments and Networking- Came into an agreement/communication with stakeholders, beneficiaries and other ventures (social or commercial) |

* | ** | ** | ** |

| Loss affordability- Using only limited amount of resources for venture at the present time |

x | ** | x | x |

| Table 4 Causation Approach in Select Social Enterprises | ||||

| Causation | Selco | Conserve India | Rangsutra | Ivillage |

| Developed the vision and marketing plan for reaching out to segment of society to be benefited | ** | * | ** | ** |

| Recognized and evaluated long-term opportunities in developing the firm | ** | ** | * | ** |

| Evaluated the expected return of recognized opportunities | ** | * | ** | ** |

| Identified the potential beneficiaries of the social solution to be provided | ** | * | ** | ** |

| Accessed information related to size and growth of demand of social solution to be delivered | ** | * | * | ** |

| Collected information about other social ventures working in the similar market and compared their products/services | * | ? | x | x |

| Table 5 Optimization Approach in Select Social Enterprises | ||||

| Optimization | Selco | Conserve India | Rangsutra | IVillage |

| Best suppliers- acquired best sources of the resources |

** | ? | x | ** |

| Standardized Resources- combined standardized high quality and ready-to-use resources |

** | ? | x | ** |

| Resource capability- resources demonstrated capabilities for the specific application for which they were conceived |

** | * | * | ** |

| Human capital- acquired/employed skillful workforce |

* | x | * | ** |

| Resource reconfiguration- reconfigured the resources to meet the need of continuously changing (dynamic) environment |

** | ** | x | * |

| Table 6 Improvisation Approach in Select Social Enterprises | ||||

| Improvisation | Selco | Conserve India | Rangsutra | Ivillage |

| Set of actions- decided a series of improvised actions to address the problem |

** | ** | * | * |

| Compared with previous problems- Compared the present situation to the problems and their solutions from the past |

* | * | x | x |

| Learning and referent- chose a referent while learning from the previous problems |

x | * | x | x |

| Resource reconfiguration- Reconfigured the resources to address the social problem in an improvised way |

** | ** | x | * |

| Knowledge– took decision on the basis of knowledge for developing an improvised and efficient social solution. | * | * | * | * |

| Table 7 Social Bootstrapping Approach in Select Social Enterprises | ||||

| Social bootstrapping | Selco | Conserve India | Rangsutra | Ivillage |

| Resource communities- created resource communities through resource pooling |

? | x | * | * |

| created resource communities through resource exchanges | x | * | x | * |

| Built social legitimacy- by projecting an acceptable and appropriate image of venture to community partners |

* | ** | * | x |

| through rational behavior (towards resource providers) and demonstration of social value creation capabilities | * | * | ** | * |

| Opted for un-utilized or under-utilized resources- through free resource networks and partnerships (scavenging) |

x | ** | ** | x |

| through social appealing and gaining access to under-utilized or un-utilized resources by persuading providers through effective and convincing proposals | x | ** | * | ? |

| through enticing proposals and storylines advocating doing good for society | x | * | * | ? |

Selection and Development of Case Studies

The alternate template strategy necessitates that different theoretical perspectives be applied to give an explanation of a series of actions (Langley, 1999). Consequently, actual entrepreneurial actions require being recognized and taken into consideration for analysis. The authors, therefore, decided to focus upon the case histories of some significant social enterprises of India that contributes to the sector of their operation in the country. The authors ended up selecting four major SEs operating in India, on the basis of the impact and social transformation they have brought in the country. For the purpose of enriching case histories and having detailed information about the entrepreneurial actions at various venture stages, a number of webinterviews, reports and magazine articles were checked thoroughly in addition to the related websites and web-pages of selected SEs and were confirmed by all the authors.

The major focus in developing the case studies was to comprehend the action and behaviors of social entrepreneur as they created and developed their specific social venture. The multiple sources of data enabled the authors to increase the validity of the cases that were evaluated. Each case was critical evaluated on the basis of resourcing behaviors and patterns found in the venture. The details of the social enterprises under study have been summarized in Table 1 below:

Case I - Selco

Selco venture has installed around six thousand solar solutions till date by understanding the basis of problems within its context and providing solutions by analyzing and resolving them. Also, at Selco the solutions are crafted on the requirements of poor people and in fact these people are significantly involved in innovations and venture operations and are looked upon as partners. The organization believes in high quality solutions that are supported by a service network. The major building block of the organization for its rural operations is their Energy Service Centers which involves the marketing, selling, installing and providing services to the clients and customers. Selco collaborates with various micro-finance institutions, public & rural banks, cooperative banks, and farmers that assists in building strong networking for providing financial solutions. The workforce of Selco reveals a merge of the different ethnicity, gender, caste and color of people based in segment of areas under social transformation to ensure trust, compassion and understanding among clients and the venture.

The investment structure of the social venture is well crafted that enables it to achieve financial sustainability while maintaining social goals by (a) partnering with other SEs and impact investors, and (b) focusing on long term speculations in workforce/stakeholders and operations. Selco makes use of three different dimensions for scaling impact (a) reaching out more people at the bottom of economy over different geographical regions, (b) building an exclusive networking with partners that plays an important role in innovation and policy making, and (c) taking accountability of overall venture mission through the proper execution of entrepreneurial role and standpoints. Moreover, the venture also represents the notion of inclusive impact by combining internal processes and operations to control the imbalances within and outside the organization. Back in 2005, the prices of Selco products were increased as a result of external solar subsidy programs. But the organization successfully controlled the situation by changing the type of products they were offering, and increasing the number of suppliers. Furthermore, the SE made considerable utilization of ground knowledge by ranging from conducting of training & mentorship sessions to inputs from practitioners view point for framing policies.

Case II – Conserve India

Conserve India is focused on the mission to reduce and remove plastic waste and converting it into high fashionable and useable products. The raw materials i.e. plastic wastes are directly collected by rag pickers that works like partners for the organization. The rag pickers working with Conserve India earns more than double of what a normal rap pickers earns. Usage of non- polluting material makes the organization more energy efficient as well as environment friendly in addition to its basic social function. Faced with the challenge of recycling with available infrastructure, the organization used iterations and experimentation, and came with the concept of up-cycling (to wash, dry and convert the bags into useable material) the plastic material for producing various fashionable products like wallets, handbags and belts. Conserve India supports hundreds of people from disadvantageous society by training them to remove the mountain of plastic wastes and then converting it into useable products. The useable products are sold and the profits earned are spent in the same segment of societies for various uplifting programs like education, personal welfare, and assistance in day-to-day activities. Conserve India works in collaboration with many top designers and sells its products online through its online website conserve-shop.

Case III - Rangsutra

During the initial period of its start the founder of Rangsutra started looking for capital and loans but was unsuccessful. With self-financing and some contributions from friends and family as well as making the craftsmen shareholders of the company, the founder made a small beginning. Presently, the venture is community-owned social enterprise of around 4000 artisans from rural areas and regions of India. Around 3000 artisans are direct shareholder of Rangsutra and, 70% of the members are women artisans. Back in 2009 the organization suffered from some difficulties in balancing the profit making and wages in a competitive environment. This urged a change and improvement in the working of artisans/stakeholders as well as looking for an inclusive and scale-able business model. The organization started professionally training their artisans for running the social enterprises with the help of some micro-finance institutions. The framing of policies and decision making as well as in making new changes and bringing around innovation is done by involving the artisans. It sells its handmade products to different retail portals like ‘Fab India’ and ‘Ikea’ in and outside India. The revenue earned is also invested in different social uplifting programs such as education and healthcare within the context of artisans and other disadvantageous people of specific communities.

Case IV - Ivillage

Ivillage manufactures designed products like home décor and wedding clothing by employing and empowering women. The designs are inspired from Indian traditions arts and are also infused with western styles. The primary mission of the organization is to nurture the talent of women artisans and make them a living so that they can work independently and support their families. The organization provides basic education facilities as well as vocational trainings to rural women. It aims at ensuring employment for rural women and a market for the products made by them. The raw materials for manufacturing handicrafts are taken from easily available sources as well as are also produced by artisans themselves. The artisans also share a network among themselves which enables them to help each other while working independently. One of the major challenges Ivillage came across was to configure the artisans with the technology oriented strategies especially online wholesaling and retailing approaches. The SE trained and mentored its artisans in alignment with technological trends and is continuously dedicated to the overall development of its workforce. Ivillage has also collaborated with other women oriented NGOs and social enterprises like Pardada and Pardadi Foundation to hone the talent of rural women and improve their lifestyle. The organization got around 200 permanent artisans that are working independently and earning while contributing to the development of handicraft industry of India. Thus, Ivillage is not only helping out rural women financially and socially but also promoting the niche of traditions Indian handicraft designs.

Analysis and Results

Based on the examination of the resource activities of these enterprises, data was matched with the resource approaches. The fit between the qualitative data in each case study and the behaviors associated with each resource approach provides evidence that a specific resource approach is relevant for explaining the resourcing behavior of a particular social enterprise. The fit between the data in the cases and behaviors associated with resource theories is depicted by ‘* mark. The ‘**’ represents a very strong fit between the data and behaviors associated with resource theories, the ‘*’ signify that the evidence was not much strong and was not supported by multiple data sources, the ‘X’ represent that the action or decision of social entrepreneur did not match the behavior associated with the resource approach. Furthermore, there were instances wherein it was impossible to clarify whether the social entrepreneurs’ actions align with the behavior of resource approaches. Such outcomes have been marked as ‘?’ in tables 2-7 Based on the analysis, conclusions about the homogeneity and dissimilarities of behavior of each of the resource approach are drawn.

For assessing the usefulness of bricolage theory in explaining the action and behaviors of social enterprises in context of cases, the criteria of bricolage definition and its four major domains is examined. The domains of bricolage includes – making do (bricolage definition), combination and reuse of resources, use of minimal-value resources and people involvement. All of the social enterprises were involved in ‘making do’ and thus it shows that this domain is the most evident one. Also all of the social entrepreneurs were engaged in people involvement i.e., involving beneficiaries, customers or suppliers in developing solutions. The founders of two of the four social enterprises (Conserve India and Ivillage) went for combining available resources rather than seeking resources from outside for developing a social solution. Only one of the four ventures (Conserve India) involved re-uses of resources for reason for other purposes.

The data in the cases also reflects that even if all of the social entrepreneurs applied some domains of bricolage (see table 2) but none of them involved the use of bricolage across multiple domains. Thus, evading generation of “mutually reinforcing patterns” which is somewhat similar to results of study of (Fisher, 2012) and fits with the propositions of (Baker & Nelson, 2005) which states that selective bricolage facilitates growth. Consequently, it becomes clear from the data that bricolage approach is useful for resource access and resource acquisition and is shall be considered by social ventures in their early stages of development.

In assessing the effectual behavior, four major dimensions of effectuation were used to validate the data which are – flexibility, experimentation, pre-commitments and networking, and loss affordability. The results of the behavioral fit of effectuation with the cases are summarized in table-3. The results depicts that the dimensions of the effectuation chosen are valuable for describing the actions of social entrepreneurs in the case studies examined in the research. Behaviors related to flexibility and pre-commitments and networking were constantly applied by all four social ventures. Pre-commitments and networking was another useful dimension in examining the behaviors of social entrepreneurs in all four cases. This supplements the authors to propose that involving network engagement is useful for social enterprises survivability. The dimension of effectuation that was comparatively less useful for explaining the actions of social entrepreneurs was loss affordability. Only one of four social entrepreneurs i.e., Conserve India used loss affordability in its actions of resourcing.

In assessing whether causation is a useful approach for explaining the action and behaviors of social entrepreneurs, the authors examined criteria related to six major dimensions of effectuation – developing the vision and marketing plan, recognizing and evaluating long term opportunities, evaluating the expected return of recognized opportunities, identifying the potential beneficiaries, assessing size and demand of social solution, and comparison with other social enterprises operating in the similar market. Five of the six domains of effectuation except comparison with other social enterprises were quite useful in examining the action and behaviors of social entrepreneurs. The alignment and fit of the data with behaviors is summarized in table- 4. All of the four social ventures shown strong fit with majority of the behaviors of causation except the last domain of comparison with other social ventures. The fit provides an insight that causation aids social enterprises in amassing resources to exploit identified social problems.

Across the four social ventures analyzed, only two social entrepreneurs demonstrated actions that fit with the behaviors of the optimization approach. The domains of the optimization used for analyzing the fit of the data are – best suppliers, standardized resources, resource capability, skillful workforce, and resource reconfiguration in dynamic environment. Two of the five domains i.e., resource capability and resource reconfiguration shows strong fit with the data which has been summarized in table-5. The data gives another useful insight regarding optimization approach in social enterprises. It signifies that optimization can be used in social entrepreneurship for resource reconfiguration in dynamic or continuously changing environment.

Improvisation has five major dimensions – deciding set of actions to address the problem, comparing with previous problem, choosing a referent while learning, reconfiguring resources, and knowledge (Hmieleski & Corbett, 2003). Three of five dimensions, i.e., deciding set of actions to address the problem, resource reconfiguration and knowledge management were evident to analyze the data in case studies significantly. One of the four social ventures i.e., Conserve India shows strong fit with each domain of the improvisation. By deriving insights from the table-6 improvisation also seems to be a significant approach for social enterprises to reconfigure resources in an improvised way.

The three dimensions for bootstrapping are – creating resource communities, building social legitimacy and opting for un-utilized or under-utilized resources (Jaywarna & Jones, 2017). One of the three dimensions i.e., building social legitimacy through rational behavior towards resource providers shows strong fit with the data in case studies. The data suggests that through rational behavior towards resource providers and demonstrating them the social value creation capabilities of the venture, social entrepreneurs can easily access and acquire resources required to develop social solutions. Notably, social bootstrapping seems to be a significant resourcing approach for resource acquisition in early and pre-emergence stages of social enterprises.

Discussion

The analysis of the data in the case using different resource approaches reveals many interesting and novel insights about each resource theory. The basic process underlying each approach is resourcing i.e., resource access, resource mobilization and resource combination (or reconfiguration). Each approach contributes significantly towards acquisition and management of resources in social enterprises at specific stages. From the behavioral comparison of resource theories, and analysis, it can be seen that there do exists the pattern of similarities among the resource approaches but they actually differ from one another. The insights that prominently come into view across the resource approaches comprises of following: (1) available resources sustains opportunity recognition in social enterprises; (2) action-taking as a catalyst for addressing resource constraints in SEs; (3) beneficiary involvement as a mechanism for social venture development and survivability. These insights have been discussed individually as follows:

Available Resources as a Catalyst for Opportunity Recognition in Social Enterprises

An entrepreneur recognizes opportunities and attempts to meet them with appropriate resources. If the entrepreneur does not have an access to the resources that are required to recognize and seize that opportunity, then the process of acquiring resources may be perceived as significantly challenging (Brush, Manolova, & Edelman, 2008). The easily available and manageable resources can be a solution to this problem. Resource approaches – bricolage and effectuation reflects that the resources which can be easily managed by a social entrepreneur sustains opportunity recognition in social enterprises. To build a good resource base for sustainability the SEs gather resources (physical inputs, human inputs and institutional inputs) in fresh ways for value creation (Baker & Nelson, 2005). In bricolage approach, entrepreneurs meet opportunities by ‘making do with available resources’ (Baker & Nelson, 2005). Therefore, bricolage helps social entrepreneurs to solve the problems with the available resources and sustains opportunity recognition. In effectuation, starting with means depicts how entrepreneurs make significant decisions by focusing on the manageable resources asking “Who am I”; “What do I know?” and “Whom do I know to uncover opportunities?” instead of focusing on a predefined objective (S. Sarasvathy & Dew, 2008). Thus, there is an important relationship between entrepreneurial action for meeting recognizing opportunities and meeting them with manageable resources.

The findings suggest that across all the resource approaches there exist a significant relationship between available resources and entrepreneurial opportunity recognition, (Fisher, 2012) proposed that – entrepreneurs who identify opportunities based on the manageable available resources will act more readily for the identified opportunities. Thus the discussion leads to the following proposition:

Proposition 1: Easily manageable and available resources enable opportunity recognition in social enterprises.

Action-Taking as a Catalyst for Addressing Resource Constraints in SEs

The second common behavior emerging from this study is - action taking is a catalyst for addressing resource constraint in social enterprises. The most important finding in results was that all the social enterprises showed an inclination towards action-taking and engagement with opportunities instead of thinking of whether a feasible solution can be worked out with what is at hand. The action taking course made it possible for social entrepreneurs to solve the resourceconstraints problem in initial stages of their functionality and acts in a way to solve the problem of resource constraints so as to derive best solutions. In the study, SEs addressed the problem of resource constraints by – (i) Optimizing the resources for problems requiring high quality of products; (ii) actively experimenting with different alternatives to find out the best possible solution; (iii) leveraging the at-hand resources (e.g., available plastic material, discarded products, rural crafts) in formulating possible social solutions; and (iv) involving customers & beneficiaries and acting as per their feedback; (v) improvising to reinforce resource reconfiguration in dynamic environments. The resource approaches that sustain action taking course are – bricolage, effectuation, optimization, improvisation and social bootstrapping behavior. The most significant and novel insights originating from discussion and results are captured in the following propositions:

Proposition 2- Bootstrapping mechanism enhances social enterprise to access resources in their early stage as well as refines their resource-building capabilities.

Proposition 3 - Improvisation facilitates social enterprises to reconfigure their resources in dynamic environments for addressing the social problems.

Proposition 4 - Optimization enhances social enterprises to avail standardized ready-to-use resources.

Beneficiary Involvement as a Mechanism for Social Venture Development and Survivability

The third most prominent dimension embedded in the study is a beneficiary involvement as a mechanism for social venture development and survivability. Entrepreneurs who are actively engaged a community of potential customers are more likely to (i) create more appealing products or services, and (ii) experience higher levels of venture growth as compared to entrepreneurs who do not engage a community of potential customers (Fisher, 2012). Bricolage behavior comprises involvement of beneficiaries, customers or suppliers in developing social solutions. Effectuation behavior involves coming into agreement/communication with stakeholders and beneficiaries. Causation behavior involves identification of potential beneficiaries of the social solution to be provided. Social bootstrapping behavior involves building social legitimacy and social appealing. In all of the four cases, social entrepreneurs showed strong inclination towards involving customers and beneficiaries. The involvement of customers/beneficiaries before the production and after delivery of products/services helps in sensing and seizing the opportunities. The capability to involve beneficiaries in decision making seems to be noteworthy especially in nonlinear and dynamic environments. The discussion can be encapsulated in following proposition:

Proposition 5: Beneficiary involvement by social ventures helps them to sense and seize opportunities especially in continuously changing environments.

Furthermore, from the theoretical perspective, above discussion and results it is also noticeable that - bricolage assists the social enterprises for creating something from available resources, socially oriented bootstrapping is suitable for accessing resources, effectuation helps to recognize opportunities, causation aids in amassing resources to exploit identified social problems, optimization enhances to avail standardized ready-to-use resources and improvisation contributes to the resource reconfiguration in dynamic environments of social enterprises.

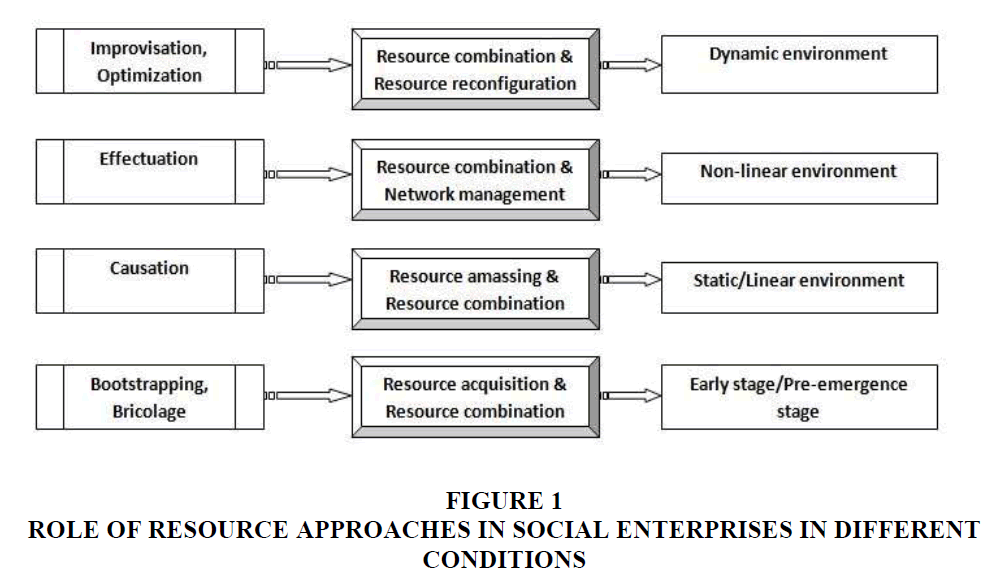

The results also endows that the resource approaches have their specific applicability in particular environments and stages of a social enterprise. Following figure highlights the role of each approach in resourcing social enterprises in different situations and conditions.

The Figure 1 also highlights the contribution of each resource approach at specific stages and conditions in social enterprises.

Conclusion and Opportunities for Future Research

The study describes how select social enterprises amass and mobilize resources in a variety of environments and internal stages. The article provides a useful agenda of using the considered approaches for theorizing resourcing concept in social enterprises. It is important to realize how these theories are essential at specific conditions (and stages) of a social enterprise and how they can be combined together for resource mobilization and configuration. Furthermore, it is also useful to recognize the significance of these approaches in decision making process of social entrepreneurs. The propositions of this paper shall form the stage for empirical studies in future and the test of their validity. The article will be a significant for both social entrepreneurs and policy makers to develop solutions to the problem of resource constraint. Future studies could also explore the use of these research approaches at the individual levels. Researchers may also consider the conditions where one or more of these resource practices are combined with other theories and constructs leading to increased network, resource access, sustainability and social value creation. The prepositions shall strengthen the discussions on the organizational learning and knowledge management for resourcing social enterprises in dynamic environments.

References

- Bacq, S., & Eddleston, K.A. (2018). A resource-based view of social entrepreneurship: how stewardship culture benefits scale of social impact. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(3), 589-611.

- Baker, T., Miner, A.S., & Eesley, D. T. (2003). Improvising firms: Bricolage, account giving and improvisational competencies in the founding process. Research Policy, 32(2), 255-276.

- Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329-366.

- Brush, C. G., Manolova, T. S., & Edelman, L. F. (2008). Properties of emerging organizations: An empirical test. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(5), 547-566.

- Churchill, N. C., & Thorne, J. R. (1989). Alternative financing for entrepreneurial ventures. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 13(3), 7-9.

- Combs, J. G., Ketchen Jr, D. J., & Short, J. C. (2011). Franchising research: major milestones, new directions, and its future within entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(3), 413-425.

- Corner, P. D., & Ho, M. (2010). How opportunities develop in social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 635-659.

- Desa, G., & Basu, S. (2013). Optimization or bricolage? Overcoming resource constraints in global social entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(1), 26-49.

- Di Domenico, M., Haugh, H., & Tracey, P. (2010). Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 681-703.

- Duymedjian, R., & Rüling, C.-C. (2010). Towards a foundation of bricolage in organization and management theory. Organization Studies, 31(2), 133-151.

- Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019-1051.

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2003). Bricolage versus breakthrough: distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2), 277-300.

- Hatton, E. (1989). Lévi-Strauss's bricolage and theorizing teachers' work. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 20(2), 74-96.

- Hmieleski, K. M., & Corbett, A. (2003). Improvisation as a Framework for Investigating Entrepreneurial Action. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Proceedings.

- Janssen, F., Fayolle, A., & Wuilaume, A. (2018). Researching bricolage in social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(3-4), 450-470.

- Jaywarna, D., & Jones, O. (2017). Resourcing Social Enterprises: The Role of Socially Oriented Bootstrapping Practices. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Proceedings.

- Jones, O., & Jayawarna, D. (2010). Resourcing new businesses: social networks, bootstrapping and firm performance. Venture Capital, 12(2), 127-152.

- Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691-710.

- Leybourne, S., & Sadler-Smith, E. (2006). The role of intuition and improvisation in project management. International Journal of Project Management, 24(6), 483-492.

- Miller, T. L., & Wesley, C. L. (2010). Assessing mission and resources for social change: An organizational identity perspective on social venture capitalists ‘decision criteria. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 705-733.

- Nelson, R., & Lima, E. (2020). Effectuations, social bricolage and causation in the response to a natural disaster. Small Business Economics, 54(3), 721-750.

- Nicholls, A. (2010). The legitimacy of social entrepreneurship: Reflexive isomorphism in a pre–paradigmatic field. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 611-633.

- Ozdemir, S. Z., Moran, P., Zhong, X., & Bliemel, M. J. (2016). Reaching and acquiring valuable resources: The entrepreneur's use of brokerage, cohesion, and embeddedness. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(1), 49-79.

- Peredo, A. M., & McLean, M. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the concept. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 56-65.

- Rutherford, M. W. (2015). Strategic Bootstrapping: Business Expert Press.

- Sarasvathy, S., & Dew, N. (2008). Effectuation and over–trust: Debating Goel and Karri. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(4), 727-737.

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 243-263.

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2009). Effectuation: Elements of entrepreneurial expertise: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2003). Guest editors’ introduction to the special issue on technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2), 181-184.

- Simon, H. A. (1959). Theories of decision-making in economics and behavioral science. The American Economic Review, 49(3), 253-283.

- Sinthupundaja, J., & Kohda, Y. (2019). Effects of corporate social responsibility and creating shared value on sustainability Green Business: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications (pp. 1272-1284): IGI Global.

- Weerakoon, C., Gales, B., & McMurray, A. J. (2019). Embracing entrepreneurial action through effectuation in social enterprise. Social Enterprise Journal, 15(2), 195-214.

- Winborg, J., & Landström, H. (2001). Financial bootstrapping in small businesses: Examining small business managers' resource acquisition behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(3), 235-254.

- Witell, L., Gebauer, H., Jaakkola, E., Hammedi, W., Patricio, L., & Perks, H. (2017). A bricolage perspective on service innovation. Journal of Business Research, 79, 290-298.

- Zahra, S. A., & Wright, M. (2016). Understanding the social role of entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies, 53(4), 610-629.

- Zelikow, P., & Allison, G. (1999). Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (Vol. 2): New York: Longman.