Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 2

Strategic Issues of Tourism Destination In Indonesia: Are They Market Ready?

WILOPO, BRAWIJAYA UNIVERSITY

MOHAMMAD IQBAL, BRAWIJAYA UNIVERSITY

RIZAL ALFISYAHR, BRAWIJAYA UNIVERSITY

ARI IRAWAN, BRAWIJAYA UNIVERSITY

Abstract

This study explores issues related to tourism destination marketing, particularly for the government acting as the Destination Management Organization (DMO). Despite the significance of T&T in generating revenue streams for local governments, there is an issue of awareness in the context of marketing readiness. To date, regions have succeeded in harvesting its tourism potential in the form of an increased number of visits and receipts. The tendency of most regions in Indonesia to explore and exploit tourism potential via branding and promotion strategies had overwhelmingly seen as a basic need. This study is qualitative by employing the use of a case study as a strategy of inquiry with thirteen respondents participated in this study. Preliminary findings in this study suggest that although the promotions and branding activities utilized as a means of marketing strategy, nonetheless competitiveness of tourism destination in fulfilling experiences remains problems to be solved.

Keywords

Marketing Management, Tourism Marketing, Tourism Competitiveness.

Introduction

Travel and Tourism (T&T) has become part of the largest industry and a massively growing sector in the world. As a massively increasing phenomenon, the T&T reflects a context of multidimensional aspects, characterized as physical, social, cultural, economic, and political (Ghasemi & Hamzah, 2014). The T&T industry contributes to the national economy across the globe, as indicated by the gross domestic product (GDP), sources of employment, export, and taxation. Globally, tourism had been one of the primary sources of wealth as the growth in the number of arrivals and receipts continue to increase. As per the International Tourism Highlight of 2019 (UNWTO 2019), it provides evidence of how massive the contribution that T&T has, especially in the Asia Pacific, out-performed other regions as the fastest-growing region in this sector respectively. Another staggering fact with regard to T&T in Asia Pacific is the contribution it has to the economy, indicated by 7 percent of growth, which is significant to leverage the global T&T to a remarkable sustained growth within the decade.

As a smokeless industry, T&T had become an essential catalyst in economic and social development in various countries. On a global scale, the impact of tourism development is influenced by large-scale changes in the economy, changing corporate governance dynamics, demographic demands, and technological changes (Milne & Ateljevic, 2001). Furthermore, on a national scale, the framework of macro-economic policy, monitoring of infrastructure, and issues related to socio-cultural cohesiveness have an essential role in the impact of tour-ism development (Milne & Ateljevic, 2001) (Table 1).

| Table 1 The Contribution of International Tourist Arrivals and Receipt | |||||||

| No | Region | International Tourist | International Tourist | ||||

| Arrivals (in Mil) | Receipts (in USD bn) | ||||||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

| 1 | Southeast Asia | 113.2 | 120.4 | 128.7 | 117.2 | 130.6 | 142.3 |

| 2 | North-East Asia | 154.3 | 159.5 | 169.2 | 168.9 | 168.1 | 188.4 |

| 3 | Oceania | 15.6 | 16.6 | 17 | 46.7 | 57.4 | 61.1 |

| 4 | South Asia | 25.3 | 26.6 | 32.8 | 33.8 | 39.9 | 43.6 |

| Asia-Pacific | 308.4 | 323.1 | 347.7 | 366.7 | 396 | 435.5 | |

In a developing economy such as Indonesia, T&T sector indulges the economy due to its growth (7.8 percent), exceeding the global average of 3.9 in 2018. And even more, T&T con-tributed IDR 890,428 billion (USD 62.6 billion) and nearly 13 million jobs to the Indonesian economy. Thus, one in three of all tourism jobs in the ten countries that make up Southeast Asia is Indonesia (WTTC 2019). Under these facts, Indonesia had proclaimed to be the third-largest T&T economy after Thailand and the Philippines. Understanding the significance that T&T has for the country, tourism development has been one of the most popular research themes in Indonesia. It was not until the success of regional destinations such as Banyuwangi, Batu, and Raja Ampat had tourism development received significant attention from local government in Indonesia. In developing favourable tourism destinations, few local governments in Indonesia have followed their predecessors' paths progressively. Regency of Banyuwangi-East Java, as an example, pioneered the steps to develop its tourism via innovative activities (i.e., festivals) and maximizing its promotional channels.

Moreover, utilizing its digital society has contributed to the Regency of Banyuwangi being awarded "Public Policy Innovation and Governance" from the UNWTO (Muafi et al., 2018). Another example of the regional tourism development is the City of Batu, East Java. Batu has built its theme in the cluster of man-made tourism destinations, which had fruitfully leveraged itself among other man-made tourism destinations (i.e., Jakarta, Bandung, Bogor) as described in an earlier study by Muafi et al. (2018). Thus, the development of regional tourism development is an integral part of the national tourism development, directed to develop the region and align the growth rate in tourism between regions in Indonesia.

Despite the significance of T&T and how it evolved as revenue streams for local governments, there is an issue of awareness in the context of marketing readiness. So far, regions have succeeded in harvesting their tourism potential in the form of increasing visits and receipts.

The tendency of the most region in the exploration and exploitation of tourism potential via branding and promotion strategies had overwhelmingly seen as a basic need. Nonetheless, employing to that of strategy in leveraging the competitiveness of the tourism destination remains questionable, as there is a lack of justification for how those strategies are determined. Moreover, most of the literature in tourism marketing has adopted the terminology of promotion and branding derived from the basic concepts of marketing with its famous "nine core elements", emphasizing on the strategy, tactics and value that shifts from a product-centrism to customer-centrism and ultimately, the human-centrism (Kotler et al., 2010). Thus, T&T strongly reflects the interaction of product-service-human and intertwined with each other.

Nevertheless, issues with concerns on the readiness of how tourism destinations should promote themselves are still insufficiently explored. Thus, a critical question that should be answered: "what are the challenges of local governments to market their tourism from stake-holder's point of view"? To date, research in the context of tourism marketing in Indonesia had mostly been in the context of consumer behaviour with much focus on a behavioural out-come such as (re)visit intention, customer/tourist' satisfaction-loyalty; and, destination image-city/nation branding (i.e., Nursanty et al., 2016; Pujiastuti et al., 2017; Foster & Sidhartais, 2019; Bastaman, 2019; Murti, 2020; Suhartanto et al., 2019). Nonetheless, the strategic issues subsequent to the readiness of a destination prior to being marketed had yet being uncovered. Thus, this study dives into the unexplored areas, particularly from the stakeholders' experience point of view.

Literature Review

Tourism Development as Indonesia’s Strategic Agenda

Indonesia's tourism destination potential has mostly been driven by the richness of its natural resources resulting in both comparative and competitive advantage. The Indonesian Ministry of Tourism realizes the potential by imposing a state's Law (No. 50/2011) on the Master Plan of National Tourism Development 2010-2025 as guidance of tourism develop-ment for the Ministry of Tourism to promote 50 National Tourism Destination widespread across 34 provinces in Indonesia, consisting 222 National Tourism Development Zones (KPPN) and 88 National Tourism Strategic Areas (KSPN). As one of the actors responsible, the local government has the responsibility in managing, facilitating, and identifying potentials to create economic value for the local economy. Hence, they necessitate identifying and developing various marketing strategies to maximize the attractiveness of their tourism destination.

The competence and capacity of local governments in managing their regions becomes an entry point to build superiority in optimizing the regional wealth, leveraged through potential tourism destinations. The relationship between tourism development and competitiveness aligns with the context of Resource-Based View (RBV) discussed by a prominent scholar (Barney, 1991), arguing that competitive advantage can is achieved through the successful creation of resources that are hard to duplicate by competitors (i.e., assets, capabilities, organizational processes, attributes, information, knowledge). Further, to be a potential source of competitive advantage, the underlying resource package must be scarce, valuable, could not be replicated, and irreplaceable (Barney, 1991). Other resourceful aspect for organizations particularly for local governments as a destination management organization (DMO) is knowledge. As a crucial aspect, knowledge has the role to strengthen organization positioning and role, despite environmental disruptions (Iqbal et al. 2020). Moreover, knowledge complements intangible resources in their support of institutional performance (Muwardi et al., 2020). Thus, local government should be aware that tourism destination performance is a representation of the DMO’s capableness and superiority.

Due to that of importance, the tourism development in Indonesia, particularly regions focusing on the exploration and exploitation of nature-based tourism have the prospect to flourish similar to other third-world destinations (i.e., China, Egypt, India, Turkey, Thailand, Costa Rica) which exploited tourism sector as one of their primary wealth generators (Echtner & Prasad 2003). Following their review on Dahles' (2002) paper, Hampton & Jeyacheya (2015) provide the fact that tourism in Indonesia was planned primarily for Bali and Yogyakarta. Moreover, the strategic focus on these destinations was mainly driven by increasing popularity with international tourists and the clear economic potential of tourism over traditional exports (Hampton & Jeyacheya, 2015). As a strategic agenda, the tourism sector had repeatedly been focused upon by the central government under Joko Widodo's administration as he urges all related agencies to bolster and boost all aspects required to support Indonesia's tourism development (https://www.indonesia.travel/gb/en/news/president-jokowi-appreciates-the-20-38-tourist arrivals-rise-in-5-months-of-2017, accessed on February 10, 2020).

As an important agenda in the quest of leveraging its T&T, a positive outcome had been proven within the last few years as Indonesia's T&T competitiveness had significantly been boosted by the price competitiveness, ICT readiness as well as human resource and labor market pillars respectively (Table 2). Despite aspects that have enhanced Indonesia's tourism competitiveness, other than those three, still needs strong support. As such, (1) health and hygiene; (2) environmental sustainability; and (3) infrastructure remains to be three pillars that are relatively underrated. Thus, the Indonesian government should become aware to emphasize more efforts to boost those underrated pillars to leverage the nation's T&T competitiveness.

| Table 2 Indonesia’s T&T Competitiveness Index | |||||

| Sub-Index | Pillars | Score | Global Rank | ||

| 2017 | 2019 | 2017 | 2019 | ||

| Enabling Environment | Business Environment | 4.5 | 4.7 | 60 | 50 |

| Safety & Security | 5.1 | 5.4 | 91 | 80 | |

| Health & Hygiene | 4.3 | 4.5 | 108 | 102 | |

| Human Resource & Labor Market | 4.6 | 4.9 | 64 | 44 | |

| ICT Readiness | 3.8 | 4.7 | 91 | 67 | |

| T&T Policy and Enabling Conditions | Prioritization of Travel & Tourism | 5.6 | 5.9 | 12 | 10 |

| International Openness | 4.3 | 4.3 | 17 | 16 | |

| Price Competitiveness | 6 | 6.2 | 5 | 6 | |

| Environmental Sustainability | 3.2 | 3.5 | 131 | 135 | |

| Infrastructure | Air Transport Infrastructure | 3.8 | 3.9 | 36 | 38 |

| Ground and Port Infrastructure | 3.2 | 3.3 | 69 | 66 | |

| Tourist Service Infrastructure | 3.1 | 3.1 | 96 | 98 | |

| Natural and Cultural Resources | Natural Resources | 4.7 | 4.5 | 14 | 17 |

| Cultural Resources and Business Travel | 3.3 | 3.2 | 23 | 24 | |

| Overall | 4.16 | 4.3 | 42 | 40 | |

The Marketing of Tourist Destination

Over the past decade, academic interests in the discussion of tourism marketing have soared significantly. Dolnicar & Ring's (2014) review has highlighted the fact that 30 per-cent of tourism articles published between 2008-2012 were those that cover marketing-related content. Further, these authors (Dolnicar & Ring 2014) have classified the theme of tourism marketing into two areas of focus. First, the marketing-related tourism research by content area, which was proposed by Grönroos' (2006a) conceptualization of marketing that encompasses the making, enabling, and keeping promises to consumers (Dolnicar & Ring, 2014). And the second form of knowledge was derived from Rossiter (2001, 2002), who postulated five categories of marketing knowledge' existence: concepts, structural frame-works, empirical generalizations, strategic and research principles (Dolnicar & Ring, 2014). The traditional marketing concept has emphasized more on the process of selling products through a mixture of marketing procedures and policies, encompassing mixtures of twelve elements (i.e., product planning, pricing, branding, distribution channels, personal selling, advertising, promotions, packaging, display, servicing, physical handling, fact-finding, and analysis). These aspects were then simplified into a widely known 4Ps Product, Price, Promotion, Place of marketing mix by McCarthy in 1964 into a concept of marketing, known and applied today (Constantinides, 2006). Since marketing does not merely associate with tangible products but also intangible ones such as services, T&T remains to be a service-type sector that offers a series of experiences (Soteriades, 2012).

The implementation of the marketing concept in T&T activities can be reflected through knowledge build-up of key aspects that include: destination image, city branding, market segmentation, and internet marketing. These aspects are crucial as they complement each other in the implementation of destination marketing. Indeed, key ingredients are needed in the development of the tourism destination. In a study by Echtner (2002) on third-world tourism marketing, the 4As of tourism-attractions, actors, actions and atmosphere-were introduced as an approach that results in series of destination clustering (i.e., oriental, sea-sand and frontier); stereotyped for the purpose of establishing certain promotional mixtures of strategy. Despite the fame of the concept in tourism marketing, the 'A's' of tourism remains be-ing enhanced in the quest to develop a successful destination. Buhalis & Amaranggana (2013) suggests that successful destinations are achieved via the 6A's of tourism destinations: (1) Attractions that comprise of natural, man-made or cultural; (2) Accessibility-adequacy of available transportation system between or within destination; (3) Amenities-services facilitating a convenient stay, namely accommodation, gastronomy and leisure activities; (4) Available-service bundles by intermediaries to direct tourists' attention to certain unique features of a respective destination; (5) Activities-available activities at the destination which mainly trigger tourists to visit the destination; and (6) Ancillary services-supporting services at the core destination not primarily aim for the tourist but heavily needed by one such as a bank, postal service and hospital.

Another important attribute to note is community participation. According to Trunfio & Campana (2019), community participation is a thrust to the destination's innovativeness that could be categorized in three forms: coercive, induced, and spontaneous participation. Whether it is a coercive, induced, or spontaneous participation, a tourism destination should always emphasize on the awareness and acquiescence among its stakeholders as they are key actors of a successful tourism destination. And apart from the attributes of idealistic tourism destination, soft infrastructure had been mentioned in previous research that encompasses the mixture of hospitality services and interactions made by person-to-person subsequent to tourists' overall experience (Pearce & Wu 2015). Furthermore, it is represented by attributes such as (1) emotional labor and sincerity; (2) quality service and professionalism; (3) creating understanding and the role of language; (4) performance and spectacle; (5) immersion and participation; (6) authentic local voices; and, (7) crowding and close encounters (Pearce & Wu 2015).

Tourist Experience and Product-Service Marketing Logic

According to Buhalis (2000), tourism destinations depend on their primary tourism products as key pull factors motivating tourists to visit them. Further, destinations offer mixtures of tourism products and services triggered by a brand or image of the destination (Buhalis, 2000). A destination's brand or image might reflect or trigger a tourist's expectation, experience, and ultimately drives one's satisfaction. According to Larsen (2007), the expectation is the first aspect of the tourist experience to be highlighted as it is an individual's ability to anticipate, belief formation, and to predict upcoming events. Hence, expectation partly relates to an individual's traits and specific expectations directed at various tourist events. Individual's psychological state considered as elements of tourist experience such as motivation, value systems and attitudes, personality traits, and self-esteem (Larsen, 2007).

In tourism, service is the primary product among others (i.e., crafts, foods, and beverages). According to Chackho (1996) tourism services are more than just image, differentiation-benefits offered, but also consistency among the various offerings and the positioning statement that guides it. Moreover, tourism is dependable to service as it does not only serve as an activity but also as: (a) a value creation mechanism rather than market offerings category; (b) a mechanism of marketing logic; (c) a value-in-use creation; and, (d) creation of inter-action rather than exchange (Grönroos, 2006b). Service providers (i.e., intermediaries) usually plans, design or create product attributes that tailor the need of their potential customers (i.e., tourists/visitors) and in exchange, amount of money is received from that activity paid by the customers via interactions of product delivery and the needs. This occurs when service is valued as an activity. On the contrary, when service is not merely seen as an exchange mechanism but as an interaction mechanism, "the customer should feel that they are better off in some way than before as compared to the expected support of other service providers" (Grönroos, 2006b).

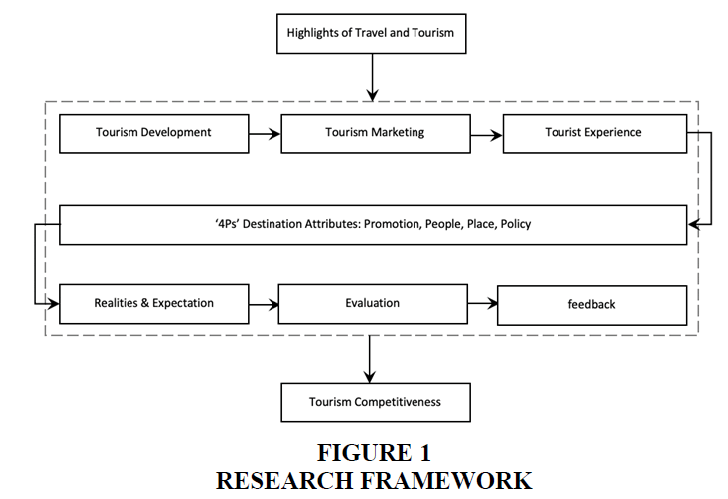

While the bulk of studies in tourism marketing have overwhelmingly been researched by focusing on behavioural outcome tourists as a primary unit level of analysis such as satisfaction, loyalty, and psychology-related themes (Dolnicar & Ring, 2014), perspectives on strategic context are still scarce. Viewing the context of tourism from a strategic marketing lens is an approach that allows plentiful research opportunities. Moreover, these authors (Dolnicar & Ring, 2014) contend that regardless of a considerable amount of applied market segmentation research, positioning strategies are very rare being interpreted into tailor-made new products or customized branding or pricing strategies. And extending the argument, tourist self-experience on a particular destination had seldom been used as useful feedback in the establishment of a strategic direction among tourism providers (i.e., government-businesses). Thus, explorations undermining experiences must take place as an avenue in the creation of established tourism destinations (Figure 1).

Research Method

This study is qualitative in nature by employing the use of a case study as a strategy of inquiry following Cresswell's (2018) guidance. A case study is employed due to its applicability in investigating a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-world context, particularly when the boundaries are yet to be clear (Yin, 2018). Following to what Decrop (1999) noted on his views with regard to qualitative approach in tourism research, "qualitative research is often qualified as 'bricolage' or 'art' in contrast with quantitative research, which is honored as being rigorous and scientific". Furthermore, it enriched previous studies in Indonesian tourism (i.e., Muafi et al., 2018; Komaladewi et al., 2019; Handaru et al., 2019) with similar approach may benefit Indonesian government to clearly understand some fact-findings of strategic issues that escalate. This study took place by exploring East Java's main tourism destination: Banyuwangi and Greater Malang (Malang and Batu). A focus group was established as a case study protocol as that of the method been used in marketing research (Yin, 2018). The focus group was designed to accommodate stakeholders representing business in tourism destinations, groups of intermediaries (i.e., travel agents), village tourism community, representation of local government, and social media marketing enthusiasts who participated in the focus group. Issues related to this re-search was based on a focused premise on the '4Ps' of destination attributes (People, Place, Promotion, Policy), pivotal for tourism. In the process of the data collection, a number of 13 participants were distributed into four different groups based on four-issues determined: information, infrastructure, services and hospitality, and government policy. A semi-structured interview was then conducted at a further stage, which complements the triangulation process via a thorough interview in each of the small groups.

As listed (Table 3), initials of key informants, together with their occupation, are presented. These lists of names participated in the study, which took place in Malang, Banyuwangi (East Java), and Mataram (Lombok). For this case study, thirteen people participated in the focus group discussion, three of whom were females, and ten were males. The participation of key informants in this study are clustered as follows:

| Table 3 Lists of Focus Group Discussion Participants | ||||||

| No | Key Informant | Gender | Age | Code | Occupation | Place of Origin |

| 1 | DN | Female | 28 | DN28 | Travel Blogger and Reviewer | Malang |

| 2 | RN | Female | 30 | RN30 | Travel Blogger and Reviewer | Jakarta |

| 3 | NJ | Male | 34 | NJ34 | Travel Blogger and Reviewer | Jakarta |

| 4 | AR | Male | 32 | AR32 | T&T Volunteer Group | Malang |

| 5 | PT | Female | 28 | PT28 | T&T Adventure Tourism Community | Malang |

| 6 | FQ | Male | 34 | FQ34 | Local Community for Village Tourism | Malang |

| 7 | SP | Male | 41 | SP41 | Local Community for Village Tourism | Malang |

| 8 | IR | Male | 29 | IR29 | Village Enterprises Consultant | Mataram |

| 9 | MR | Male | 44 | MR44 | Agency for Tourism and Culture, Banyuwangi Regency | Banyuwangi |

| 10 | BS | Male | 49 | BS49 | Agency for Tourism and Culture, Malang Regency | Malang |

| 11 | SPY | Male | 51 | SPY51 | Large Tourism Enterprise | Batu |

| 12 | AF | Male | 37 | AF37 | Entrepreneur/Media Group | Mataram |

| 13 | LGA | Male | 51 | LGA51 | State Owned Enterprise for Tourism Development | Mataram |

1. Travel bloggers and reviewers. Representing T&T reviews whose online platforms are widely available such as travelingyuk.com, lonelyplanet.com, and tripadvisor.com (DN28, RN30, and NJ34);

2. Local community incorporating the village tourism as well as volunteer groups in Greater Malang surroundings (AR32, PT28, FQ34, SP41);

3. Local authorities, responsible for the development of regional tourism destinations in East Java, represented by the Regency of Banyuwangi and Malang (MR44, BS49); and,

4. Enterprise professionals of whom represent the media, small and large enterprise professionals (IR29, SPY51, KM48, AF37, LGA51).

Results and Discussion

Gaps of Information and Experience in Destinations: A Virtual Reality

The emergence of the internet and social media have overwhelmingly changed how travellers access information, how trips are planned and booked, as well as how these individuals share their experience (Hays et al., 2013). Furthermore, the rise of social media platforms has shift-ed types of traveler's involvement in sharing information to further collaborate, communicate, and establish various content published through YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram. These platforms allow the facilitation of consumer-generated content (CGC), nowadays commonly used by online travelers (Hays et al., 2013). The respondents noted:

1. "Nowadays, whenever people are planning to travel either for luxury or backpacking, the internet is the main source information that they are dependent on" (DN28).

2. "Internet is not only used as a browsing platform to search for important attributes of tourism destination but also, as a media to advocate others (friends, family, community) linked with the internet" (RN30).

Hence, travelers' information dependency in the online source is inevitable. Not only is that information useful to identify someone's needs prior to their visits but also, it serves as one of the ultimate promotional tools of a particular destination. While these responses were aimed to enquire general perspective from the travel bloggers on the information available on the internet, the question went deeper to cultivate tourist experience in relevance to information adoption by raising a question: "what do you think is the gap between information provided with reality (experience) in the tourism destination?". Answers were obtained and led to an initial conclusion as there were few issues determined by the respondents. First, despite the promotional activities being focused on tourist destinations, visitors are still lacked important information. One respondent mentions that:

"What they have promoted in websites are how the destinations being visualized on the in-ternet and advantages that travelers will benefit, gaps still exist, such as if the place is not accessible by public transport and where/to whom they should seek for information" (RN30).

In a similar vein, another respondent concurs to that response by adding:

"What they have promoted in websites are how the destinations being visualized on the in-ternet and advantages that travelers will benefit, gaps still exist, such as if the place is not accessible by public transport and where/to whom they should seek for information" (RN30).

Second, an important attribute for the visitor is information on local transportation (how to get there? by what? how much?) and public facilities available at the point of destination. It is imperative that visitors understand clearly as their mobility becomes an important aspect of reaching tourist destinations easily. Evidence indicated that such information is relatively in-sufficient or could be misleading. It was confirmed that:

"Information is sometimes unclear, lacked on-site public facilities, transportation some-times was not informed, and functioning of tourist information center (TIC) is yet to be effective" (FQ34).

The response provided by the respondent (FQ34) was based on his experience in handling traveler's anxiety towards lacked information that they had experienced. In response to that, the local government representatives (MR44, BS 49) were confirmed regarding that issue, they noted:

(1) "I think most local government would experience a similar situation. It is difficult expecting us to handle every information content, maintaining our website, social media because we are limited to our daily duties as public servants, the Regent decided to ap-point creative locals and employ them to create promotional content for the media, but difficulties of local transportation reach are still present. We have the TIC, although it is less effective because the information is available online" (MR44).

(2) "Public transport to reach a specific destination are sometimes very rare, information on prices of chartered transport are often inconsistent, the transports are self-owned, and travelers had to bargain the price themselves. We have problems in updating every important information on our tourism because we have to handle administrative duties. Most of the time, we rely on local tourism communities to collaborate in creating promotional content. TIC is available and operated by the government, but I don't think visitors use it often, but do not hire other people to operate it and handle media" (BS 49).

These facts contradict the notion of service-marketing logic that expects customers should be driven to create their own value on ones' consumption and make them feel comfortable with no means to compare with other service intermediaries (Grönroos 2006b). Moreover, understanding that travelers are attached so heavily on social media platforms and create various information allows individuals to easily contribute their thoughts, opinions, and creations to the internet as means of disseminating their online peers (Hays et al. 2013). Thus, when expectation does not meet reality for tourists, it could lead to criticism, complaints, and negative perception about a particular destination being blasted in social media and any other platforms on the internet.

Imperatives of Infrastructure and Destination’s Value as a “Place” to Visit

An attribute that is no less important than the destination is infrastructure. It is a pivotal component in boosting the quality of entities involved in regional tourism activities. Thus, better infrastructure results in a better quality of tourism destination. The respondents were asked: "how could infrastructure trigger a destination as a place to visit?". In fulfilling the adequacy of infrastructure, the Regency of Banyuwangi had been aware of nurturing accessibility, amenities, attractions, and commitment. Like a shred of evidence, the respondent noted:

"In order to develop accessibility, the first 100 days program of elected Regent in 2010 was to open up access by full functioning of the local airport operationalized in December 2010, road infrastructure from the city to tourism site was also constructed. Amenities were established, hotels and various types of accommodations were present" (MR44).

As another attribute in tourism development, the Banyuwangi regency embraces its local wisdom by offering a series of events for the whole year. A total of more than 100 events are offered in a full year calendar, comprising of cultural festivals and sporting events. It was highlighted that:

"Attractions are important for us. We have Ijen summer dance, gandrung sewu dance festival offered on a tight schedule, almost every week festivals are present. The sporting event is also another attraction that the Regent wishes to attract Banyuwangi's fame internationally, digital infrastructure such as fiber optics and electricity were established" (MR44).

In another case of tourism in the Malang regency, despite the development of hard (physical) infrastructure, there is also the need to establish soft infrastructure, as the second respondent noted:

(1) "In the Malang Regency, our agency (tourism and culture) does not have the authority to directly build access to tourism destination because we are dependent on other agencies."

(2) "Existing infrastructure reflects the strength of the local government's budget and the programs, infrastructure in the Malang Regency had yet to be in ideal conditions, but what we are currently trying to optimize are developing events, so that we could still at-tract people coming to our tourist destinations" (BS49).

Despite the limitation that local government has it enhancing its infrastructure, there is a tendency that soft infrastructure is being focused upon as a trade-off rather than solely emphasizing the existence of hard-infrastructure that depends on the political will of the local government and its budget adequacy. Furthermore, realizing the need to strengthen soft-infrastructure for the tourist destination, respondents noted:

(1) "Training and personnel development are needed for the local tourism entities such small businesses or accommodation providers to ensure businesses and services can be managed sufficiently for travelers, I think it's still very rare and not many tourist destinations have attempted to do so" (NJ34).

(2) "The ITDC has been appointed to establish special economic zone (SEZ) focusing in tourism and so far, because we have sufficient capital expenditure and will be hosting a major sporting event (MotoGP) we have to speed up physical infrastructure…but the accomplishment would be less relevant without the presence of community, the open-ness and knowledge of hospitality to be delivered to potential visitors of Lombok tourism. So far, our main problem is the lack of qualified human resources in the tourism and hospitality sector" (LGA51).

(3) "If there is something to see, experience, and interesting in that destination, triggering people to come, businesses will come and establish themselves and see it as a potential opportunity, regardless of any condition" (SPY51).

Based on what had been explored, tourism development may not necessarily correlate directly to the existence of hard-physical infrastructure but also soft-infrastructure. Inline with Pearce & Wu's (2015) argument, this study views that a traveler's experience could be triggered by an intelligent understanding of hospitality by frontlines of tourism personnel achieved through interpretive roles and the awareness of community members to welcome visitors. Adequate soft-infrastructure is reflected in the openness of local stakeholders providing services essential for visitors to consume products in tourism destination is pivotal for the development of tourism. Since tourism destination can be viewed as a complex adaptive system (Jovicic, 2017), confronting issues of determining marketing arrangements, including the division of responsibilities between public and private sector agencies (Prideaux & Cooper, 2002); and moreover, facing non-linearities of external/internal factors could contribute to change in behaviour that affects destination stakeholders. For example, limitations in infrastructure can be driven by the inadequacy of the government's annual budget to which it might be common in developing economies, nonetheless, due to efforts to boost the attractiveness of the destination's other than solely promoting hard-infrastructures, the destination may still have value and attractiveness in the view of its potential visitors. Moreover, a tourism destination's knowledge in its offering of novel attractions for travellers will further generate needs for businesses to be established and thus, driving the destination's economic value for its stakeholders.

Destination Positioning: Intersecting People and Service

As the core of marketing, positioning often viewed as the promise made to benefit the customer's needs and wants, creating expectations and offering a solution to their problems. Moreover, positioning function as an establishment and maintenance of a product/service offerings in a distinctive place in the market that potentially lead to competitive advantage (Pike, 2017). In the case of tourism, an openness that correlates to the creation of affinity offered by local stakeholders is an important feature that characterizes a destination's position relative to its competitors in a given market of similar product offerings. Also, openness corroborates with how affinity in tourism is created by local stakeholders in a particular destination to visitors as outsiders. Despite the nation's T&T competitiveness in terms of international openness (see table 2), what had been highlighted, however, contradicts the reality in a particular tourist destination. Few respondents noted:

(1) "Either domestic or international visitors, they become subject of scams because they are not the local people, and their knowledge of the surrounding area where they visit are sometimes incomplete" (NJ34).

(2) "Sometimes, the visitors are left with no choices when it comes to consuming tourism products such as local transportation, foods, and beverages or souvenirs/gifts. Often what people experienced as they make their review online is that they felt deceived by the merchants by paying more than average" (DN28).

(3) "Openness is what distinguishes Lombok with long-established Bali, the awareness and openness to outsiders are still incomparable, differences in traditions and cultural beliefs among local people (Lombok) in some areas where tourism had just started to bloom needs to be reinforced so that they are much more aware and open-minded" (AF37).

Openness to international visitors may be present in established tourist destinations in Indonesia (i.e., Bali), but as what had been perceived and experienced by the respondents, other regions would somehow be different in terms of openness and awareness of the local stakeholders viewing tourists as outsiders. Another contradiction is that despite Indonesia's international openness as a strong dimension (i.e., T&T policy and enabling conditions) in the T&T competitiveness index (Table 2), perhaps it could also be said misleading to some extent. International openness, in this sense, could reflect in government support via visa on arrival (VoA) or visa exemptions for foreigners and establishment bilateral air service agreement reflected by availability of a direct international flight to a certain destination. These examples may be a reflection of what international openness is all about. Nevertheless, measures of how the presence of visitors as outsiders in a certain destination can be compliantly accepted by the local people of the destination are yet to be answered. It raises an important issue of why experiences do not often meet the expectation of travelers. Also, issues related to the openness and awareness of local stakeholders in the service delivery to visitors remain present. It was noted:

(1) "Boycott from the local business providers are often inevitable, so travelers are forced to consume their services, terms and conditions are imposed to cater the interests service providers, the supply of services are often monopolized by local business groups" (PT28).

(2) "Tourism awareness groups (Pokdarwis) should be present in every region; the problem is not every community realizes the need to have these voluntary groups, and at certain times there are conflicts of interests of local stakeholders in viewing this group as exclusive entities" (AF37).

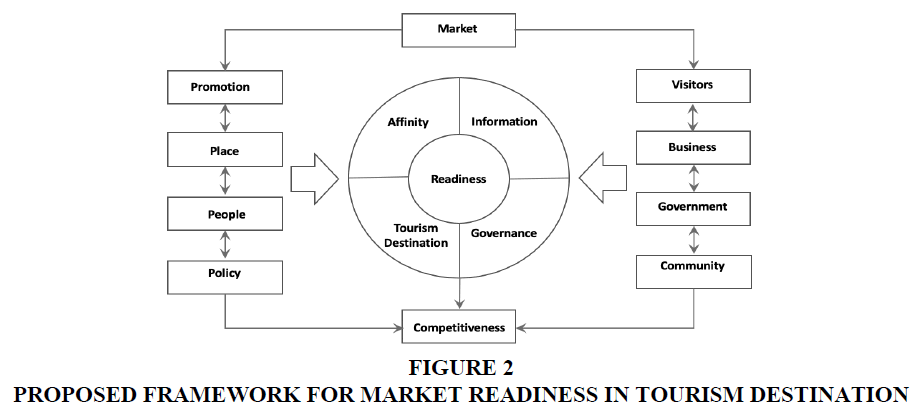

In particular, the region where tourism is realized as an economic growth mechanism, open-ness to outsiders is one of the main values for local stakeholders, leading to hospitable culture delivered by every actor within a particular tourist destination. Nonetheless, in a certain region whereby tourism had just been introduced and exploited to leverage economic competitiveness, the development programs are designed on a top-down development basis, neglecting the role of community participation and readiness from a bottom-up perspective. This study argues that important connections between local stakeholders, travelers, and hospitable services should strengthen a destination's positioning through positive destination image and ultimately functioning as a thrust in accomplishing destination's competitiveness. Hence, a proposed framework is provided based on a factual exploration of tourism destination to pursue the readiness of market development (Figure 2).

Conclusion

To conclude, this study has explored important issues of the challenges for local government in Indonesia in order to market tourism destination. Despite being an important agenda of development in Indonesia, troublesome issues from the perspectives of tourism development and marketing together with tourists' experiences remain dilemmatic to cope with. Furthermore, issues highlighted in this study could provide a basis for future development, as reflected in a proposed framework for market readiness.

These issues relate to important four attributes in a tourism destination: (1) a one-sided promotion undertaken by local government in its role as DMO by neglecting readiness of the destination and its product offering; (2) partial relatedness among stakeholders of tourism destination, as visitors are sometimes being left alone and must deal with trouble-shooting their own problems faced in the tourist destination; (3) affinity to tourism and openness are still problems that must be diminished, particularly via strong knowledge-based of services encounter by the local stakeholders (i.e., local businesses, local communities, and local government); and (4) policy support and programs by DMO should be created on a bottom-up basis and readiness to market should be determined to establish destination positioning and branding, not only due to complement annual government budget. The negligence towards such issues by these actors may hamper the valuableness of the tourist destination and, thus, being less competitive in the view of potential visitors.

Apart from the findings in this study, this study is not without its limits. Despite its intention to explore relevant issues in the tourism marketing context, this study is limited to the context of few destinations being the locus of the study and, thus, may not be generalizable due to the qualitative nature of this study. Furthermore, the proposed framework is yet to be conclusive but providing an avenue for further research. Despite the availability of appraisal and evaluation systems to determine the destination's positioning, a thorough managerial check, and accommodating specific measurement tools could be developed to ad-dress issues relevant (Pearce & Wu 2015).

References

- Barney, J., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D.J. (2001). The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. Journal of Management, 27(6), 625-641.

- Barney, J.B. (2001). Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management, 27(6), 643-650.

- Bastaman, A. (2018). Bandung city branding: Exploring the role of local community involvement to gain city competitive value, 6(1), 22.

- Buhalis D., & Amaranggana A. (2013) Smart tourism destinations. In: Xiang Z., Tussyadiah I. (eds) Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014. Springer, Cham.

- Chacko, H.E. (1996). Positioning a tourism destination to gain a competitive edge. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 1(2), 69-75.

- Constantinides, E. (2006). The Marketing Mix Revisited: Towards the 21st Century Marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(4), 407-438.

- Cresswell, J.W., & Cresswell, J.D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (fifth ed.). USA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Dahles, H. (2002). The politics of tour guiding: Image management in Indonesia. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(3), 783-800.

- Decrop, A. (1999). Triangulation in qualitative tourism research. Tourism Management, 20(1), 157-161.

- Dolnicar, S., & Ring, A. (2014). Tourism marketing research: Past, present and future. Annals of Tourism Research, 47, 31-47.

- Echtner, C. M. (2002). The content of Third World tourism marketing: a 4A approach. International Journal of Tourism Research, 4(6),

- Echtner, C.M., & Prasad, P. (2003). The context of third world tourism marketing. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 660-682.

- Foster, B., & Sidhartais, I. (2019). A perspective from indonesian tourists: The influence of destination image on revisit intention. Journal of Applied Business Research, 35(1), 29-34.

- Ghasemi, M., & Hamzah, A. (2014). Proceedings from the 5th Asia Euro Conference.

- Grönroos, C. (2006a). On defining marketing: Finding a new roadmap for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(4), 395-417.

- Grönroos, C. (2006b). Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 317-333.

- Hampton, M.P., & Jeyacheya, J. (2015). Power, ownership and tourism in small islands: Evidence from Indonesia. World Development, 70, 481-495.

- Handaru, A.W., Nindito, M., Mukhtar, S., & Mardiyati, U. (2019). Beach attraction: upcoming model in bangka island, indonesia. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 18(5), 1-12.

- Hays, S., Page, S.J., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Social media as a destination marketing tool: Its use by national tourism organisations. Current Issues in Tourism, 16(3), 211-239.

- Iqbal, M., Siti Astuti, E., Trialih, R., Wilopo, Arifin, Z., & Alief Aprilian, Y. (2020). The influences of information technology resources on Knowledge Management Capabilities: Organizational culture as mediator variable. Human Systems Management, 39, 129-139.

- Jovicic, D.Z. (2019). From the traditional understanding of tourism destination to the smart tourism destination. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(3), 276-282.

- Komaladewi, R., Mulyana, A., Indika, D.R., & Bernik, M. (2019). Culinary development model: destination attractiveness to increase visits. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 18(6), 1-12.

- Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2018). Marketing 3.0: From Products to Customers to the Human Spirit. In: Kompella K. (eds) Marketing Wisdom. Management for Professionals. Springer, Singapore.

- Larsen, S. (2007). Aspects of a psychology of the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 7-18.

- Milne, S., & Ateljevic, I. (2001). Tourism, economic development and the global-local nexus: Theory embracing complexity. Tourism Geographies, 3(4), 369-393.

- Muafi, M., Wijaya, T., Diharto, A.K., & Panuntun, B. (2018). Innovation strategy role in tourists visit improvement. context of man-made tourism in Indonesia. Journal of Environmental Management and Tourism (2), 304-309.

- Murti, D.C.W. (2020). Performing rural heritage for nation branding:A comparative study of Japan and Indonesia. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(2), 127-148.

- Muwardi, D., Saide, S., Indrajit, R.E., Iqbal, M., Astuti, E.S., & Herzavina, H. (2020). Intangible resources and institution performance: The concern of intellectual capital, employee performance, job satisfaction, and its impact on organization performance. International Journal of Innovation Management, 24(05).

- Nursanty, E., Suprapti, A., & Syahbana, J. A. (2017). The application of tourist gaze theory to support city branding in the planning of the historic city Surakarta, Indonesia. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 13(3), 223-241.

- Pearce, P.L., Wu, M.Y., & Chen, T. (2015). The spectacular and the mundane: Chinese tourists’ online representations of an iconic landscape journey. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(1), 24-35.

- Pike, S. (2017). Destination positioning and temporality: Tracking relative strengths and weaknesses over time. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 126-133.

- Prideaux, B., & Cooper, C. (2003). Marketing and destination growth: A symbiotic relationship or simple coincidence? Journal of vacation marketing, 9(1), 35-51.

- Pujiastuti, E.E., Nimran, U., Suharyono, S., & Kusumawati, A. (2017). The antecedents of behavioral intention regarding rural tourism destination. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(11), 1169-1181.

- Rossiter, J.R. (2001). What is marketing knowledge? Stage I: forms of marketing knowledge. Marketing Theory, 1(1), 9-26.

- Rossiter, J.R. (2002). The five forms of transmissible, usable marketing knowledge. Marketing Theory, 2(4), 369-380.

- Soteriades, M. (2012). Tourism destination marketing: approaches improving effectiveness and efficiency. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 3(2), 107-120.

- Suhartanto, D., Brien, A., Primiana, I., Wibisono, N., & Triyuni, N.N. (2019). Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Current Issues in Tourism, 1-13.

- Trunfio, M., & Campana, S. (2019). Drivers and emerging innovations in knowledge-based destinations: Towards a research agenda. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 14.

- World Economic Forum (2019), The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index, Retrieved from:https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-travel-tourism-competitiveness-report-2019

- World Travel & Tourism Council (2019), Economic Impact Report, Retrieved from: https://wttc.org/en-us/About/About-Us/media-centre/press-releases/press-releases/2019/indonesian-travel-and-tourism-growing-twice-as-fast-as-global-average

- Yin, R.K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (Sixth ed.). Los Angeles, USA: Sage Publication, Inc.