Case Reports: 2017 Vol: 23 Issue: 1

Case Study : Survival of a Market Leader In a Regional Integration of Emerging Economies: A Case Study of The Tourism Industry In Thailand

Nittaya Wongtada

National Institute of Development Administration

Donyapreuth Krairit

National Institute of Development Administration

Case Descriptions

The primary subject matter of this case concerns tourism industry, industry analysis and competition, ethics and social conflict management. Secondary issues examined include alternative analysis, alternative response selection. The case has a difficulty level of five, appropriate for first year graduate level. The case is designed to be taught in 2 class hours and is expected to require 2 hours of outside preparation by students

Case Synopsis

In September 2016, the committee of the National Tourism Policy of Thailand held consecutive meetings to consider the National Tourism Development Plan for 2017-2021. Accounting for 8.5 percent of GDP in 2015, the tourism industry was important to the country. Following the Thai military coup in May 2014, the nation’s economy had been in shambles. The revenue from tourism was more vital to the economy than ever. However, this industry brought many problems to the society, including increased natural resource deterioration and crime syndicates. Competition from other destinations, including ASEAN member countries, was becoming more intense and could be a future threat to the industry since international tourism flows will be diverted. Economic recession in several sources of tourists was a looming threat. The massive rising of Chinese tourists was serendipitous, as the country’s revenue from this group was dominating the inflow travel trade, but it is too risky to rely on a single market.

While preparing the strategic tourism plan, the committee was evaluating which of three strategic directions would be able to achieve the desirable outcomes, which include increasing revenue, sustaining natural resources and increasing the country’s competitiveness. The first direction is to concentrate on the existing mass flow of foreign visitors. With the anticipated 30 million international tourists in 2016, there were thought to be various ways to alter the current situation to meet the objectives. The second strategic option was to appeal to high-value tourists who are able to spend more for better services. The third option was to offer specific activities to attract niche markets.

In which of these options should Thailand invest its valuable resources to gain the highest benefit out of its tourism industry? This was the strategic question that the Committee was charged with answering.

Birth of Tourism

Serving as bases for US troops and airfields during the Vietnam War in 1960s, the infrastructure of Thailand was developed as sex tourism for US soldiers and veterans. As a consequence, Thailand was one of the first players in Asia to capitalize on tourism (Felix Lowe, 2006). Fortunately, the film industry helped promote Thailand for other touristic appeals beyond that of a sexual playground (Felix Lowe, 2006). In 1974, the James Bond thriller, “The Man with the Golden Gun,” helped to establish the southern Phang-Nga National Park as a new tourist attraction. In 2000, “The Beach,” starring Leonardo DiCaprio, used a serene and beautiful beach near Phuket for shooting the film, helping to intensify foreign fascination with the exotic beauty of Thailand. Thereafter, in 2012, the hugely popular comedy film, “Lost in Thailand,” brought a large number of Chinese tourists to Thailand (“Lost in Thailand film results,” n.d.). Concomitantly, international mass tourism increased due to the rising standard of living, more people acquiring more free time, and improved technology that allowed people to travel farther, faster and cheaper (“Activity 1 | The rise of tourism,” n.d.).

Tourist numbers grew from a mere 336,000 foreign visitors and 54,000 GIs in 1967 (Ouyyanont, 2001, pp.157-187) to about 30 million international tourist arrivals in 2015, generating income of 42 billion US dollars. The term “the country’s revenue from tourism” was misleading since Thailand did not receive income directly from tourists. It was circulating income where tourists’ spending in the country was circulating among those involved such as hotel owners, restaurant operators and taxi drivers. The data were collected through survey to estimate the revenue. The government receives the revenue directly from visa fees but this is not a major source of income. By 2013, the country had become the 10th "top tourist destination" based on world tourism rankings (UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2014 Edition, 2015), the second most popular destination of international tourism worldwide, and, as of 2015, the world’s seventh biggest earner from international tourism (Wong & Choong, 2015). This was an outstanding success for an emerging economy located in Southeast Asia, with only 67 million people.

Present Situation

After over five decades, the tourism industry in Thailand had evolved to have the following characteristics.

Tourist Profiles

Domestic tourism was much larger than international tourism. In 2014, there were about 25 million international tourists, while the domestic tourists had over 133.9 million trips. A person who makes several trips to a country during a given period is counted each time as a new arrival. This is the reason the number of domestic tourists exceeds the population in a country. For foreign tourists, their composition continued to shift. In the past, travelers from the US and other Western countries made up the majority of tourists arrivals in Thailand. In the mid-1970s, however, nationals from affluent nations in Asia including Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan – became the most important tourist groups in Thailand (Kontogeorgopoulos, 1998, pp. 225-238). This was because of the rapidly expanding middle class in these countries, which allowed them to increasingly travel abroad. However, in 2010’s, Chinese tourists dominated the country’s tourism trade by accounting for 19 percent of total foreign tourists in 2014, a threefold increase from 2013. In addition, Russian tourists commanded the highest growth rates in terms of the number of tourists, total revenue and spending per tourists. However, the growth of Russian tourists was fluctuating: it declined in 2015, but resumed its rate of increase again in 2016. As shown in Exhibit 1 below, if these trends continued, Chinese tourists would dominate the market.

| Exhibit 1: Tourism in Thailand | ||||

| Number of Arrivals | Total Revenue (Million Dollars) | |||

| Region | 2010 | 2014 | 2010 | 2014 |

| East Asia | 8,304,478 | 14,603,825 | 6,561.11 | 15,752.69 |

| Europe | 4,329,583 | 6,161,893 | 7,420.71 | 12,849.77 |

| The Americas | 792,190 | 1,099,709 | 1,445.12 | 2,297.89 |

| South Asia | 985,098 | 1,239,183 | 891.67 | 1,515.20 |

| Oceania | 788,229 | 942,706 | 1,346.02 | 2,078.48 |

| Middle East | 615,006 | 597,892 | 878.03 | 1,309.45 |

| Africa | 121,816 | 164,475 | 163.37 | 304.83 |

| All countries | 15,936,400 | 24,809,683 | 18,706.03 | 36,108.32 |

| Country of Residence (a) | ||||

| China | 1,122,219 | 4,636,298 | 1,084.48 | 6,177.92 |

| Malaysia | 2,058,956 | 2,613,418 | 1,201.96 | 1,879.37 |

| Japan | 993,674 | 1,267,886 | 986.65 | 1,494.45 |

| Russia | 644,678 | 1,606,430 | 1,035.08 | 3,469.83 |

| South Korea | 805445 | 1,122,566 | 777.02 | 1,341.42 |

| India | 760,371 | 932,603 | 689.26 | 1,153.47 |

| Laos | 715,345 | 1,053,983 | 391.2 | 730.49 |

| UK | 810,727 | 907,877 | 1,392.85 | 1,881.81 |

| Singapore | 603,538 | 844,133 | 533.1 | 897.05 |

| USA | 611,792 | 763,520 | 1,079.82 | 1,605.99 |

| Australia | 698,046 | 831,854 | 1,222.29 | 1,876.52 |

| Note: (a) Top sources of international tourists Source: Department of Tourism, Ministry of Tourism and Sports, Thailand |

||||

Spending Patterns

As is apparent in Exhibit 2, shopping was a favorite activity of international tourists visiting Thailand. More than half of the tourist’s expenditure went toward shopping and accommodation, as opposed to entertainment, food and local transportation. With respect to shopping, tourists from nearby regions tended to spend more on shopping, while those from distant regions spent more on accommodation. Among the top nationals visiting the country, tourists from India, Singapore, Laos and Malaysia spent at least 30 percent of their travel budget on shopping, while those from other regions, such as Australia, Japan, UK and the USA, spent more on accommodation. Those from Russia and the US paid more for entertainment and accommodation.

| Exhibit 2: Spending Patterns of International Tourists Visiting Thailand in 2014 | |||||||

| Country of | ShoppingEntertainment Sight-seeing | Accommodation | Food | Local | Misc | ||

| Resident | &Beverage | Transportation | |||||

| East Asia | 26% | 11% | 4% | 29% | 18% | 9% | 2% |

| Europe | 20% | 12% | 4% | 31% | 21% | 11% | 1% |

| The | 19% | 13% | 4% | 32% | 19% | 12% | 1% |

| Americas | |||||||

| South Asia | 37% | 10% | 3% | 24% | 16% | 9% | 2% |

| Oceania | 21% | 13% | 4% | 33% | 18% | 9% | 1% |

| Middle East | 28% | 13% | 3% | 28% | 17% | 10% | 1% |

| Africa | 33% | 8% | 3% | 29% | 17% | 9% | 1% |

| All countries |

24% | 12% | 4% | 30% | 19% | 10% | 1% |

| Country of | Shopping | Entertainment | Sight- | Accommodation | Food & | Local | Misc. |

| Resident | seeing | Beverage | Transportation | ||||

| China | 25% | 11% | 6% | 27% | 19% | 10% | 2% |

| Malaysia | 29% | 11% | 4% | 30% | 17% | 8% | 2% |

| Japan | 20% | 13% | 4% | 33% | 19% | 10% | 1% |

| Russia | 23% | 13% | 5% | 29% | 20% | 10% | 1% |

| South Korea | 24% | 13% | 4% | 30% | 19% | 9% | 2% |

| India | 37% | 10% | 4% | 24% | 15% | 9% | 2% |

| Laos | 30% | 9% | 2% | 27% | 19% | 11% | 1% |

| UK | 15% | 13% | 5% | 32% | 22% | 12% | 1% |

| Singapore | 31% | 10% | 3% | 30% | 18% | 8% | 1% |

| USA | 19% | 13% | 4% | 33% | 19% | 11% | 1% |

| Australia | 21% | 14% | 4% | 33% | 18% | 9% | 1% |

Tourists who traveled with a package tour spent more per day than non-group tourists. In 2013, only 28 percent of tourists traveled with tour groups. Even though package tour goers spent a shorter time on each trip than those who arranged their own travel, they were more active, judging from their spending more per day on shopping, food and beverage and transportation. On the other hand, non-group tourists spent more per trip since they stayed longer. Noticeably, more and more tourists planned their own travel or relied on travel agents to help them arrange their journey.

Seasonality

Tourism was highly seasonal. The peak tourist seasons were during January to March and November to December of each year (about 47 percent of foreign visitors in Thailand arrived during these five months). This coincided with a good climate (cool season) in Thailand, and unpleasant weather situations in Europe and the US, and East Asia (for example, North China, Korea and Japan) (“Tourism Statistics Thailand 2000-2016,” 2016). Nevertheless, there were some groups of tourists who did not follow this seasonal pattern. For instance, tourists from the Middle East preferred traveling during May to August to avoid the warmest period in their countries. Similarly, travelers from Australia and South Africa traveled to Thailand to escape their respective winter months during June to August. Travelers from countries in the region tended to arrive all year around depending on their holidays and school break periods. For instance, Chinese tourist arrivals peaked during long public holidays, including Chinese Lunar New Year in January or February and the Golden Week in October. Summer break in China was normally from July to the end of August allowing children to travel with their family.

Location Concentration

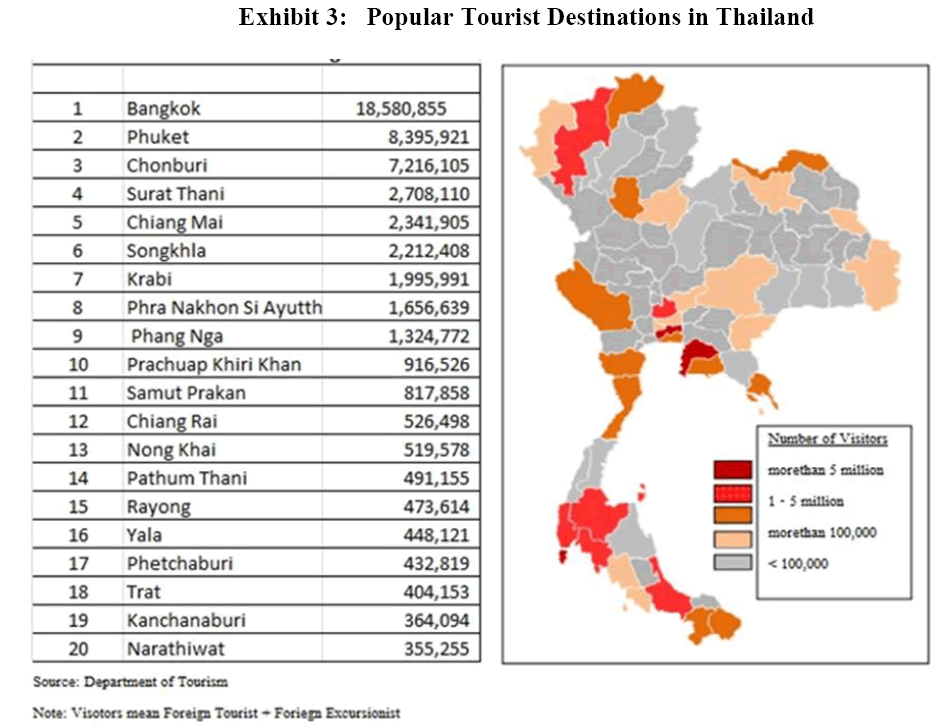

International tourism was highly concentrated in a few provinces with particular appeals (Vision for Thai tourism 2558-2560, 2016). As shown in Exhibit 3, in 2013, about 94 percent of international tourists traveled to 20 of 76 provinces of Thailand. Bangkok, the capital city, received the largest number of tourists. There were only 9 provinces which had more than one million foreign visitors per year. The attraction of six of these nine provinces was based on sea, sun and sand, while only two provinces, Attuthaya and Chiangmai, had their main attractions on culture and history.

Return visitors tended to travel farther than first time visitors. In 2015, around 60 percent of Thailand's tourists were return visitors (“Two Trillion baht revenue in tourism and marketing missions,” 2013). Compared to the general tourists, the revisiting travelers tended to travel to more locations, and so spent more money on sightseeing and entertainment. They travelled beyond popular tourists locations (i.e., Bangkok, Chiangmai and Phuket) but were still concentrated mostly in the coastal areas in the south of Thailand. However, about half of the return visitors showed a willingness to travel to new places and engage in new activities (“Study on supportive way of tourism,” n.d.). They viewed the country as a “value destination.” In 2013, each return tourist spent about USD 1,290 per visit, compared to the $1,426 per visit of the first-time visitor. Assisting TAT’s governor in forming the strategic direction of Thailand tourism, Mrs. Jutaporn Rerngronasa, TAT’s Deputy Governor for International Marketing and a veteran of TAT expressed her concern about the repeat visitors from Europe as follows.

European tourists accounted for the largest sector of repeat visitors. They were like snow birds migrating to Thailand for warm weather. Nice weather, beautiful beach, delicious food, friendly people and affordable costs were the main attractions. In recent years, they diverted to one or more of our neighboring countries, i.e., Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam to gain new experiences. These countries had relatively recently welcomed foreign visitors; and, several attractions of their countries were similar to Thailand’s.

Quality Tourists

Since 1990s, the concern that too many tourists visit few locations in a tightly compressed time had led to the drive for “quality,” as opposed to quantity tourists. Undesirable tourists were easily to spot, as they were those came to buy sex, or trade or consume illegal drugs or spent less than they consumed in terms of the country’s resources. However, there was disagreement on the definition of quality tourists (Kaosa-ard, 1994, pp.23-26). For those whose businesses catered to foreign tourists, quality tourists were big spenders who preferred well-known, international chain hotels, rode in chauffeur-driven limousines, and dined at expensive restaurants. On the other hand, from the viewpoint of socio-economists, true quality tourists were those who helped improve income distribution because they stayed in locally-owned hotels or guest houses, ate at local food stalls, and rode local transportation. From the idealistic perspective, quality tourists were those who ventured to new places to have personal contact and cultural exchange with the local people. These tourists wanted to learn about and appreciate the country’s cultural diversity.

There was some evidence that those tourists who used services provided by the locals left more income in the hands of the local people (Kaosa-ard, 1994, pp.23-26). Although the daily expenditure of this group was as not high as that of hotel dwellers, they actually spent more because they usually stayed in the country much longer (Kaosa-ard, 1994, pp.23-26). Nevertheless, Thailand's tourism boom coincided with a period of worsening income inequality, (Wattanakuljarus & Coxhead, 2008, pp.929-955) in that income from tourism did not seem to trigger down to the poor. Furthermore, expecting foreign tourists to immerse themselves in local culture was unrealistic because most tourists just wanted to enjoy and relax in a somewhat familiar environment while taking a vacation. Asia-Pacific travelers, in particular, tended to take shorter and more frequent holidays each year, and so there was little time for personal and cultural exchange.

Drawbacks

The tourism industry had both positive and negative effects on Thailand. The negative consequences of tourism were the focus of the tourism committee. Here are some of important ones.

Cultural Clashes

A conflict arising from the interaction of foreign travelers who processed different beliefs and values from those of the host culture was inevitable. Even though many locals felt uneasy with the manner of foreign tourists from various countries, the cultural clash with Chinese tourists was prominent. Locals complained about bothersome Chinese behavior, such as spitting, littering, cutting into lines, disobeying traffic laws and letting their children relieve themselves in public. Some restaurant owners complained of Chinese tourists filling up doggy bags at buffets, (Denis, 2014) as well as talking and laughing at such loud volumes as to make it difficult for other guest to enjoy their own dining experience. Consequently, over the past few years, some hotels and restaurant buffets had made it clear that Chinese were unwelcome (“Chinese tourists are causing chaos,” 2016).

Environmental Deterioration

Although Thailand earned a lot of revenue from tourism, the industry had a negative impact on the environment. More constructions in marina areas and other water-based activities ruined the ocean. High concentration of tourism activities at some seaside resorts caused damage to coastal areas. Other environmental issues were, for example, noise disturbance, air pollution, and water contamination from the disposal of sewage and solid waste (“Tourism Industry,” 2016). In the opinion of Deputy Governor Jutaporn, this problem did not originate from the tourism trade per se, but rather from the local management. She elaborated as follows.

On several occasions, TAT was blamed for over stimulating tourists to a specific location. It led to overcrowding, pollution, a higher cost of living, etc. The local management could have ameliorated the problem by just limiting the number of visitors, but they did not do it because they would rather compete for more tourists to generate more revenue. Several locations offered similar attractions. If they just worked together to provide the information to tour operators in finding alternative locations, this problem would be reduced. Doing so would be difficult, unfortunately, because it required coordination among different local governing bodies.

Safety

Among the problems that foreign visitors would face in Thailand, safety was the most serious, and sometimes, life threatening one. According to the World Economic Forum’s Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index 2015, Thailand's safety level ranked 132 out of 140, worse than Lebanon, Mali, Burundi and Iran. The increases of 54 percent in tourist deaths and 160 percent in tourist injuries between 2014 and 2015 (“Thai Officials to investigate more than 50% Rise in Tourist Deaths,” 2016) were attributed to several factors. First and foremost was a lack of basic safety standards and the poor enforcement of existing laws, factors that had combined to give Thailand the second-highest road fatality rate in the world (Fernquest, 2015). Andrew M. Marshall, author of “A Kingdom in Crisis: Thailand’s Struggle for Democracy in the Twenty-First Century,” commented on the situation as follows.

In 2014, just as in the years preceding it, there were train, bus, ferry, speedboat, motorbike and car accidents, murders, knifings, unexplained deaths, numerous suicides, diving accidents, robberies gone wrong, anonymous bodies washing up on the shores and a string of alcohol- and drug-related incidents. . . . Its tourist industry is poorly managed and the Land of Smiles has come to justifiably be regarded as one of the most dangerous tourist destinations on Earth(Paris, 2014).

This safety issue was already worsening when, in August, 2016, attackers bombed a series of popular resort cities. Two bombs went off at tourist spots in the seaside resort town of Hua Hin, killing four and injuring at least 11 foreigners (Rothwell & Palazzo, 2016).

Crime Syndicates

Increasing numbers of foreign visitors attracted crime syndicates from various countries. German, Russian, West African, Japanese the Yakuza, Chinese, and South Korean gangsters thrived in Thailand. Relatively lax Thai law enforcement and corruption of some local authorities that had the effect of weakening border control, thereby allowed foreign mob organizations to expand their operations in the country (Schmid, 2012). These crime entities tended to target foreigners from their own nationality. Prostitution, human trafficking, drug trading, real estate scams, and money laundering were among their common activities. Thus, foreign tourists ran a risk of encountering local gangsters and foreign mafia while visiting Thailand.

Revenue Leakage

The success of Thailand’s tourism industry partly was due to foreign investment in accommodations, restaurants, airlines, car rentals, tour operators, travel agents, etc. The Thai government supported and assisted foreign businesses to invest in the tourism industry. International hotel and fast food chains were pervasive in popular tourist destinations. However, there were also a lot of illegal foreign operators catering to tourists from their own home countries. For instance, Russians set up companies by using a Thai nominee to operate travel services, restaurants, luxury housing estates and five-star hotels. Because of the lack of enforcement by the Thai immigration and labor departments, these Russians operated the business as their own, avoiding taxes and not applying for work permits (Thongrod, 2016). Likewise, as tourists from Chinese were increasing, Chinese businessmen bought property, set up businesses and took jobs from locals (“Chinese tourists are causing chaos,” 2016). The magnitude of the problem was amply illustrated by the estimate that 70 percent of all money spent by tourists in Thailand ended up leaving the country (“Negative Economic Impacts of Tourism,” n.d.). Mr. Pornchai Jitnavasathien, president of Chiang Mai Tourism Business Association expressed his frustration as follows.

The Chinese were investing in long-term leasing of apartments and hostels that are converted into daily accommodations for the rising numbers of Chinese tour groups visiting Chiang Mai. They operate without permits and are located outside the popular hotels and shopping zones . . . , and are managed solely by Chinese staff. Moreover, the Chinese currency is accepted for the convenience of visitors who are tricked into buying overpriced tour packages by Chinese tour agencies (Kangwanwong, 2016).

Mr. Thawatchai Arunyik, ex governor of TAT and a consultant for various businesses in the tourism industry, echoed the sentiment of Thai operators as follows:

Instead of adopting laissez faire practices, the government should limit the amount of supply in the tourism industry. Foreign tourists, particularly Chinese, would travel to Thailand anyway. When there were too many hotels, restaurants and other services, price competition was intense among these providers, causing the revenue per tourist to be lower than the desired level. There were no poor quality tourists, just poor management. Thailand could find ways to increase revenue from existing tourists, for example, charging a fee per tourist from tour operators or imposing mandatory visits for group tours to specific outlets of local SME products.

Indeed, the government responded to the industry’s outcry by employing a hard line in controlling Chinese-related operations in order to retain more tourism revenue in the country. TAT governor Yuthasak announced that the government would set standard package prices, control types of tour buses, tour guides and shops that could serve Chinese tourists, and recommend tourism routes. Above all, existing illegal activities would be suppressed (“Prayut ordered to hold an urgent meeting on Chinese zero-dollar tours,” 2016).

Putting these policies into implementation was complicated, as could be seen in the September 2016 arrest of the owners of cheap tour packages, known as “zero-dollar tours,” on charges of fraudulent registration and illegal operations. They were accused of registering in Thailand using local nominees but taking all revenue to China without paying taxes (“Zero-dollar tour crackdown gains momentum,” 2016). Their assets were confiscated. However, instead of receiving praise from those operating in the industry, the government was besieged by requests from several tourism agents such as the Association of Thai Travel Agents and the Thai Hotels Associations which wanted to find better measures to deal with Chinese tourists (“ Tour agents urge concert measures,” 2016). They were concerned that receiving a commission from sending tourists to shop at specific retailers, a common practice in the industry, would be treated as an illegal activity. Indeed, several units in the tourism industry were interconnected. Any action or decision, the committee had to carefully weigh the benefits and costs.

Global Tourism

While Thailand was dealing with its own internal challenges, the structure of global tourism industry was shifting. The travel and tourism industry was one of the world’s largest industries, with 1,133 million visitors worldwide, and contributed close to US$ 7.6 trillion to the world global economy in 2014 (“Statistics and Facts on the Global Tourism Industry ,” 2016). The vast majority of foreign trips took place within the same regions, i.e., about four out of five global arrivals occurring in the same region. Europe and the Americas were the most popular places to visit (UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2015 Edition, 2015). However, international arrivals in emerging countries were anticipated to outpace those in developed nations before 2020 (UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2015 Edition, 2015). Globally, travel for holidays, recreation and leisure was the most important tourism motive since it accounted for more than half of all international tourists in 2014. Only 14 percent of international tourists reported travelling for business and professional purposes, while the rest travelled for other reasons, such as visiting friends and relatives, religious reasons, or medical treatment, etc (UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2015 Edition, 2015).

In addition to the shift in spatial patterns, tourist’s activities had also changed. Currently, tourism’s appeal was based on sun, sand, and sea the most vibrant sector of the tourism industry. (Global Trends in Marine and Coastal Tourism, 2016) Nevertheless, the following trends of tourism trends seemed destined to drive the direction of future industry growth.

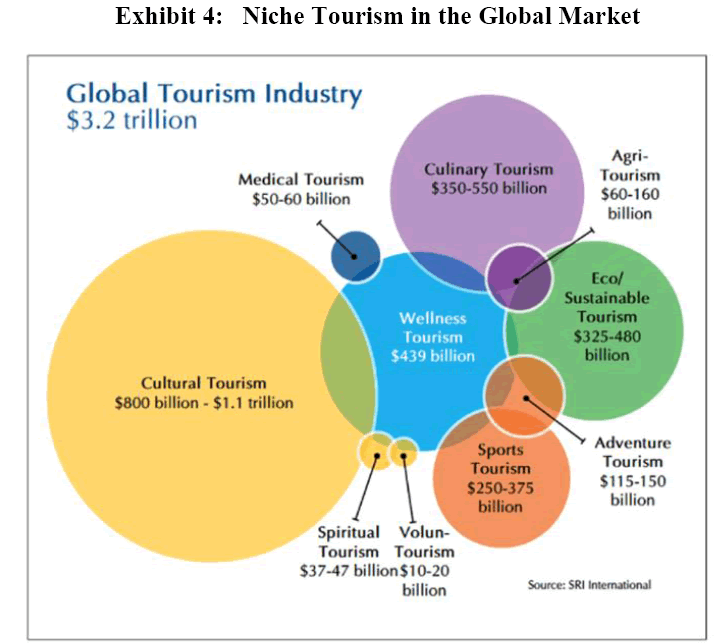

Activity-based Tourism

Activity-based tourism incorporated various activities such as bird watching, cycling, diving,Niche tourism responded to increasingly sophisticated tourists who demanded custom-made tourism activities. Even though niche tourism was composed of various segments, the niches were overlapping. In 2013, cultural tourism was the largest niche tourism segment, which was estimated to be US$ 800 billion to US$ 1.1 trillion. On the other hand, wellness tourism was smaller (US$ 439 million), but tourists in this segment were also interested in other activities, including culinary, adventure, sports and cultural tourism as shown in Exhibit 4. These niche segments were expected to expand rapidly but at different rates, e.g., cultural tourism at 2-4 percent per year (Richard, 2011), sport tourism at 14 percent (“Sports Tourism: Key drivers of Tourism,” 2014) eco or sustainable tourism between 20 percent and 34 percent per year (“Eco Tourism on The Rise,” n.d.), and wellness tourism at about 8 percent (Clausing, 2015).

Despite its high attractiveness, the market was highly fragmented, as could be readily seen in the wellness tourism niche. International wellness travelers spent on average USD 1,639 per trip, or 59 percent more than the average global tourist (The Global Wellness Tourism Economy 2013, 2013). Wellness tourism was composed of various sub-segments, including spiritual retreats, wellness cruises, beauty clinics, fitness centers, and resort spas. Spa tourism as a group was a core business within wellness tourism and accounted for a significant portion (41 percent) of the wellness tourism economy sharing, 71.5 billion in 2012 (The Global Wellness Tourism Economy 2013, 2013).

Senior Tourism

Although there was no estimation of the market size of senior tourism, older people (aged 60 years or over) would grow to reach 21.1 per cent of world population, or 2 billion in 2050(World Population Ageing 2013, 2013). In 2015, the senior population was found in many affluent nations such as Japan (26.4 million people), Germany (21.4 million), South Korea (13 million), France (18.7 million), UK (18.2 million), USA (14.7 million and China (9.2 million) (Mendiratta, 2015). Generally, these travelers preferred a higher level of comfort but perceived safety was the most important factor in their decision making and, as a result, they preferred package travel (Vojvodic, 2015). However, the behavior of senior tourists from different countries was diverse. For instance, after retirement, senior individuals in Russia experienced loss of friends and had more free time but reduced income an d so were price sensitive (Nikitina & Vorontsova, 2015, pp. 845-851). On the other hand, elder Chinese tourists were pampered by their children. Sponsoring their parents for vacation trips abroad was considered as being loyal, respectful and loving. These tourists were not sensitive to price but to quality. They usually traveled during the off-season to avoid hectic areas (Olivier, 2015).

Chinese Tourism

With over 100 million Chinese people forecasted to travel abroad by 2020, coupled with an increasingly affluent and sizeable middle class, China’s outbound tourist market affected the global tourism trade. They entered into the tourism market by traveling to foreign countries in the same region, with Hong Kong, Thailand, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan being their top five destinations in Asia. When they gained more experience in traveling abroad, they would travel outside of Asia. As a consequence, Chinese tourists traveling to Europe increased 97 percent during 2011-2014, followed by increases in travel to the Middle East (up 177 percent) and North America (up 151 percent) (Lin, 2015).

China’s outbound tourists preferred destinations with an appeal based on historical and cultural experiences, and shopping. They were keen on shopping because when they traveled abroad, they were expected to bring home gifts for relatives and friends. The Chinese were avid buyers who spent on average nearly USD 1,000 per trip when shopping abroad. (Olivier, 2015) The farther they traveled, the more they shopped (Lin, 2015). To appeal to Chinese shoppers, providing Mandarin-speaking staff and accepting China UnionPay credit cards were crucial. Marketing campaigns during Chinese national holidays, developing new product specifically for the Chinese market, and increasing visibility on Chinese online shopping portals were effective ways to lure these avid shoppers(“How to Target Chinese Shoppers,” 2016).

Asean Destination

Membership in ASEAN was another challenge for Thailand in forming a strategic tourism plan. In January 10, 2009, Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member countries agreed to collaborate on tourism strategy which intended to promote Southeast Asia as a single destination. With ten member countries, ASEAN intended to have an integrated image of the region as a destination providing diverse experiences for international tourists. The integration of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) occurred along the opening of a common AEC visa on 31 December 2015. To increase the value of the region’s tourism trade, member countries planned to offer tour packages spanning several countries (Mohamed, 2016). Currently, citizens of the ASEAN could travel to other member countries without the need for a visa.

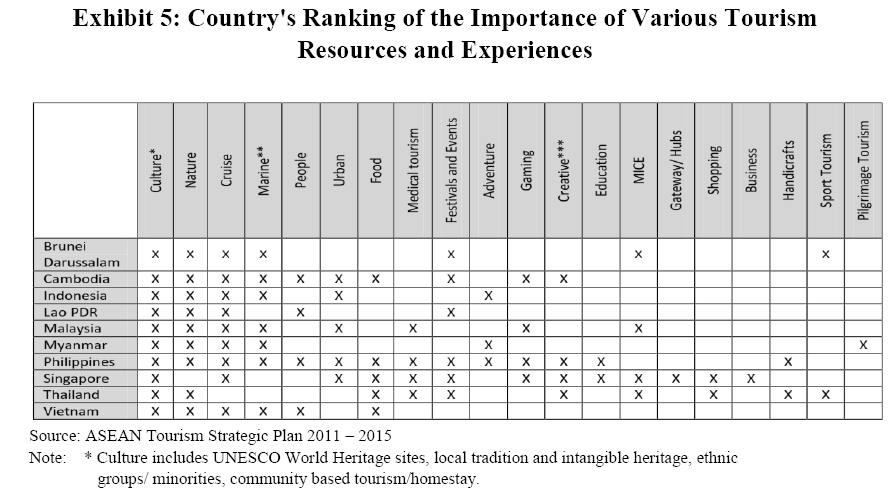

Situated in the same geographical region, ASEAN member nations inherited similar tourism attractions in terms of natural resources, culture, traditions and hospitality (Mohamed, 2016). As new participants in tourism, lesser economically developed member nations, i.e., Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam (the so-called CLMV countries), had advantages in their unspoiled nature and world renowned heritage sites. More developed nations had advantages in terms of offering sophisticated metropolitan experiences in shopping, dining, meetings, entertainment and medical services. As a group, ASEAN selected culture, nature and cruise appeals in encouraging more tourists to visit the region, as shown in Exhibit 5. (ATMS 2011-2015, 2012) (Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity, 2013) There are a number of challenges ASEAN must address if it is to succeed in its efforts to integrate the tourism sector in the region. Amongst others, these include the harmonization of visa requirements, the development of third party liability insurance, the standardization of tourism related services, the upgrading of tourism related infrastructure, and facilitation for inflow of tourists across the region (Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity, Association of Southeast Asian Nations? This collaboration was not without problems, as could be surmised by Mrs. Jutaporn’s description of tourism collaboration among ASEAN members.

It is difficult to set up a single visa across ASEAN. More economically advanced countries are more willing than the CLMV. A single visa meant member countries would lose the income from visa fees, which is more important to the CLMV. The CLMV are collaborating in offering a single visa among themselves but not extending it to other ASEAN members yet. Each of them has famous world heritage sites which make up their strengths. For instance, Cambodia has Angkor Wat which is the largest religious monument and complex in the world. Laos’ Luang Prabang, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1995, is a provincial city where time still seems to stand still. Luckily, Thailand is situated in the center of Southeast Asia which allows us to be the central airport hub of the region. We are trying to form collaboration with one CLMV country at a time.

Winners

Tourism accounted for approximately 10 percent of ASEAN GDP. ASEAN’s share in the global tourism trade increased from 7.5 percent in 2010 to 8.5 percent in 2014(UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2015). Its visitor arrivals rose significantly from 73 million in 2010 to 105 million in 2014, about half of which were intra-ASEAN (Exhibit 6).

| Exhibit 6: Tourist Arrivals in ASEAN | |||||||||

| in thousand arrivals | |||||||||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |||||||

| Country | Intra- ASEAN |

Extra- ASEAN |

Total | Intra- ASEAN |

Extra-ASEAN | Total | Intra- ASEAN |

Extra- ASEAN |

Total |

| Brunei | 109.9 | 104.4 | 214.3 | 124.2 | 117.9 | 242.1 | 115.9 | 93.2 | 209.1 |

| Darussalam1/ | |||||||||

| Cambodia | 853.2 | 1,655.1 | 2,508.3 | 1,101.1 | 1,780.8 | 2,881.9 | 1,514.3 | 2,070.0 | 3,584.3 |

| Indonesia | 2,338.5 | 4,664.4 | 7,002.9 | 3,258.5 | 4,391.2 | 7,649.7 | 2,607.7 | 5,436.8 | 8,044.5 |

| Lao PDR | 1,990.9 | 522.1 | 2,513.0 | 2,191.2 | 532.3 | 2,723.6 | 2,712.5 | 617.6 | 3,330.1 |

| Malaysia | 18,937.2 | 5,640.0 | 24,577.2 | 18,885.3 | 5,829.0 | 24,714.3 | 18,809.7 | 6,223.0 | 25,032.7 |

| Myanmar | 512.3 | 279.2 | 791.5 | 100.4 | 716.0 | 816.4 | 151.1 | 907.9 | 1,059.0 |

| The Philippines | 298.2 | 3,222.3 | 3,520.5 | 331.7 | 3,585.8 | 3,917.5 | 375.2 | 3,897.6 | 4,272.8 |

| Singapore | 4,779.6 | 6,859.0 | 11,638.7 | 5,372.2 | 7,799.1 | 13,171.3 | 5,732.7 | 8,758.5 | 14,491.2 |

| Thailand | 4,534.2 | 11,402.2 | 15,936.4 | 5,529.9 | 13,568.4 | 19,098.3 | 6,462.6 | 15,891.3 | 22,353.9 |

| Viet Nam | 688.7 | 4,361.1 | 5,049.9 | 838.4 | 5,175.6 | 6,014.0 | 1,363.8 | 5,483.9 | 6,847.7 |

| ASEAN | 35,042.8 | 38,709.8 | 73,752.6 | 37,732.9 | 43,496.1 | 81,229.0 | 39,845.5 | 49,379.8 | 89,225.2 |

| in thousand arrivals | |||||||||

| 2013 | 2014 | ||||||||

| Country | Intra- ASEAN |

Extra- ASEAN |

Total | Intra- ASEAN |

Extra- ASEAN |

Total | |||

| Brunei | 3,053.5 | 225.6 | 3,279.2 | 3,662.2 | 223.4 | 3,885.5 | |||

| Darussalam1/ | |||||||||

| Cambodia | 1,831.5 | 2,378.7 | 4,210.2 | 1,991.9 | 2,510.9 | 4,502.8 | |||

| Indonesia | 3,516.1 | 5,286.1 | 8,802.1 | 3,683.8 | 5,751.6 | 9,435.4 | |||

| Lao PDR | 3,041.2 | 738.3 | 3,779.5 | 3,224.1 | 934.6 | 4,158.7 | |||

| Malaysia | 19,105.9 | 6,609.6 | 25,715.5 | 20,372.8 | 7,064.5 | 27,437.3 | |||

| Myanmar | 218.7 | 1,825.6 | 2,044.3 | 1,598.3 | 1,483.2 | 3,081.4 | |||

| The Philippines | 422.1 | 4,259.2 | 4,681.3 | 461.5 | 4,371.9 | 4,833.4 | |||

| Singapore | 6,114.7 | 9,453.2 | 15,567.9 | 6,113.0 | 8,982.1 | 15,095.2 | |||

| Thailand | 7,410.4 | 19,136.3 | 26,546.7 | 6,620.2 | 18,159.5 | 24,779.8 | |||

| Viet Nam | 1,440.3 | 6,132.1 | 7,572.4 | 1,495.1 | 6,379.2 | 7,874.3 | |||

| ASEAN | 46,154.4 | 56,044.6 | 102,199.0 | 49,223.0 | 55,860.8 | 105,083.8 | |||

The CLMV group gained more from participating in this cooperation. Compared to more developed ASEAN members, the CLMV received fewer foreign tourists, and their revenue per tourist was less than that of their more developed counterparts. Yet, the CLMV achieved higher growth rates in both the number of arrivals and revenue receipts. As a group, it saw 123 percent increase in foreign visitors, mainly from other ASEAN nations. Their tourism receipts were had tremendously expanded by nearly fivefold. Within the CLMV group, the tourism in Myanmar performed exceptionally well. It realized a 300 percent increase in international tourists and revenue growth of 1,673 percent during the period 2010-2014. Visitors from outside ASEAN contributed a larger share of Myanmar’s tremendous growth than those from within ASEAN. Moreover, its business opportunities attracted a number of investors (Chhor et al., 2013). It had an abundance of cheap labor and was located at the center of the world’s fasting-growing region. Deputy TAT Governor Jutaporn believed that the future of the CLMV had high potential.

In the future, the CLMV will be major players in this industry. Currently, their infrastructure is underdeveloped. It is more expensive to visit these countries. Hotels cost more, and foods have limited varieties in both types and quality levels. Activities beyond the major touristic attractions like shopping, fun parks and other entertainments are limited. Likewise, the interconnectivity between cities is inconvenient. Eventually, these problems will disappear because the tourism industry has attracted a lot of investment from domestic and foreign investors.

Among more developed member countries of ASEAN, in 2014, Malaysia had the largest number of foreign tourists (27 million) following by Thailand (24 million) and Singapore (15 million). However, Malaysian’s growth rate of tourists was lower than ASEAN average. Its revenue per tourist had also declined from US$ 959 in 2010 to US$824 in 2014. A large proportion of these arrivals were intra-ASEAN, with half of them coming from Singaporeans who were budget travelers, despite their significantly higher purchasing power. They were familiar with the local lifestyles and so searched for value rather than novelty (Chong, 2016). In contrast, Thailand received the highest revenue per tourist, had a higher revenue growth rate, and welcomed more foreign tourists from outside the ASEAN than any other ASEAN country (Chong, 2016). Exhibit 6 shows such trends. Moreover, those tourists from the CLMV accounted for over forty percent of all tourists from ASEAN visiting Thailand in 2015. They came to enjoy a more metropolitan environment, shopping and medical treatment. TAT governor Yuthasak wanted to seize this opportunity by adding more direct flights between Thailand and each CLMV country, as well as facilitating the cross border travel by land (“TAT to collaborate with CLMVT countries to stimulate tourism,” 2016).

Future Direction

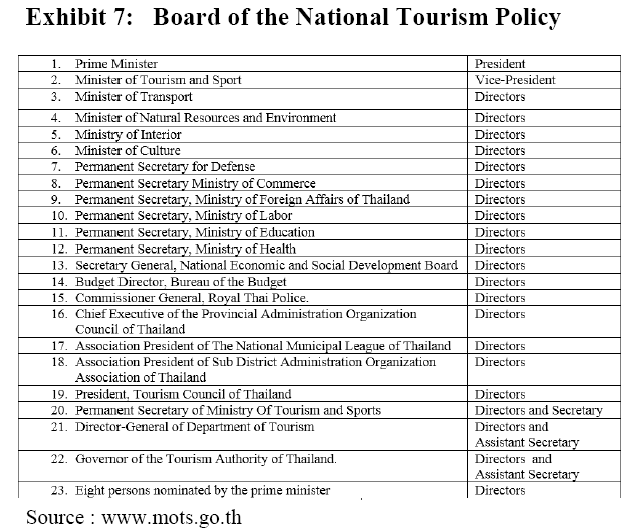

The committee for national tourism policy of Thailand was responsible for forming the National Tourism Development Plan for 2017-2021. It was composed of representatives from numerous government agencies (see Exhibit 7). In addition to shaping the country’s tourism policy, the committee was responsible for facilitating, following up on and evaluating the implementation of the policy. An anonymous source from the TAT board provided insight into the difficulty in coordinating among various agencies.

It looked good on paper that there were various governmental agencies working together in promoting and managing the tourism industry. Unfortunately, in practice, these government units were independent, and acted autonomously. It was difficult to coordinate among these agencies. Even though they had a good intention to help, they could not control every unit in their organization. Thus, good intention did not always translate into implementation. On several occasions, their actions hurt the tourism industry. For example, local newspapers reported a car accident between a Thai and drive-in tourists who did not have any local auto insurance policy. Instead of enforcing the insurance requirement, the Land Transport Department banned visiting motorists from driving beyond the province of entry in June 27, 2016. Chinese tourists in Northern provinces dried up. Also, many Chinese elected to travel to neighboring countries instead. Now, the Ministry of Transport is considering removing this restriction.

Potential Next Moves

Whichever the strategic direction of Thailand tourism, the committee members agreed that their choices must be able to fulfill multiple objectives: increasing income from tourism, retaining more revenue in the country, having a more even income distribution, preserving natural resource and social sustainability, reducing seasonality, and sustaining the country’s competitiveness. With these objectives in mind, the committee was considering these three main directions of foci

Current Tourists

If current tourists were the center of focus, there were many challenges associated with maintaining and attracting this massive tourist flow. The problem from overcrowding tourists and others would be exacerbated if the number of tourists were allowed to continue expanding without better management. Chinese travelers would increase further because Thailand was a short-haul flight and viewed as a value-for-money destination with good airline connections and convenient visa application on arrival (Muqbil ,2013). In 2016, about 10-20 per cent of Chinese visitors were from the high-end market, 30-40 per cent for the middle market, and 50 per cent for the low-end segment (Jirarushnirom, 2016). Chinese tourists who travelled to a foreign country for the first time chose to travel with the tour group. They were budget travelers who pursued neither adventure nor luxurious accommodation, and were price sensitive (“Eco Tourism on The Rise Current situations and trends in tourism.,” 2015). They wanted to see the most popular tourist spots and did not know much about local customs. If this group was overlooked, Thailand would miss a global opportunity. Other countries would welcome them with open arms.

The popularity of Thailand among Chinese tourists may arise from the current situation in the region, as described by Deputy Director Jutaporn.

The dispute about the South China Sea put China in conflict with Brunei, Cambodia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. So, traveling to these countries was not encouraged. Chinese officials view tourism as closely linked to larger diplomatic strategies. China’s Approved Destination Status (ADS) policy allowed only government-approved travel agencies to offer group package tours and acquire visa in bulk to countries that the Chinese government had approved their ADS status. Thailand was not a party in this conflict and so was on the list of approved destinations.

High-Value Tourists

Expanding upscale products and services to accommodate high-end tourists was another option. Based on research projects on high-value foreign visitors, commissioned by the TAT in 2013, the high-value tourists from China, India, Russia and ASEAN countries shared common profiles: they were more likely to have college degrees, be younger than 45 years old, exude more self-confidence, reside in large and prosperous cities, and travel abroad more often than the general population in their respective countries. The high value tourists were defined as those with monthly income of at least US$ 1,500. They spent more for each trip and stayed longer. Interestingly, they shared similar preferences to the general tourist, including shopping, coastal areas, diverse activities and food. However, they required superior and personalized services. Thailand was perceived positively but as a value destination, not a luxury one, and not a very safe place. Given a choice, they would rather travel to more developed nations such as the USA and European countries. hown in Exhibit 8, the market size and spending per trip of this segment was estimated in the aforementioned research projects. Mr. Yuthasak proposed to the committee to focus on bringing in more quality tourists as the most important strategic direction because he believed that this group could upgrade the industry, as well as increase the revenue. However, appealing to this segment would not be a new strategy, as seen in Mrs. Jutaporn’s explanation below.

| Exhibit 8: Contribution of High Value and Niche Segments | ||

| Number of | Spending | |

| tourists | per tourist (USD) | |

| High Value Segment : | 1,509,113 | 2,734 |

| China | 509,198 | 3,520 |

| Russia | 74,000 | 3,750 |

| India | 20,992 | 3,150 |

| ASEAN | 904,923 | 2,199 |

| Niche strategy: | 3,336,291 | 1,712 |

| Wedding & honeymoon | 755,691 | 1,289 |

| Health | 360,797 | 1,707 |

| Golf | 347,961 | 663 |

| Eco-tourism | 858,340 | 1,180 |

| MICE | 1,013,502 | 2,841 |

| Other tourists: | 5,796,439 | 480 |

| Wedding & honeymoon | 287,993 | 529 |

| Health | 497,543 | 798 |

| Golf | 399,900 | 281 |

| Eco-tourism | 4,611,003 | 314 |

| Source: Department of Tourism, Thailand | ||

TAT’s past five-year plan, which would end in 2016, stressed the importance of this segment. We put together promotional activities to entice this group and had a certain level of success. Currently, about 5 percent of our international tourists were from this group. More five star hotels, Michelin restaurants, and other exclusive activities sprang up in Bangkok and Phuket to serve this market. Nevertheless, the ultra-high income group still hesitated to visit Thailand because they viewed our country as a common location plagued with crime, drug, and sex trade, and as an unsafe place.

Niche Tourism

The development of niche markets such as meetings, incentives, conferencing, exhibitions (MICE), healthcare holidays, ecotourism, and weddings & honeymoons could help Thailand to differentiate its tourism from neighboring countries. In 2013, 66.9 percent of foreign tourists visiting Thailand were for a “general” visit, 11.8 percent for business, 5.8 percent for visiting friends and relatives, 3.4 percent for meeting or seminar and 12 percent for specific activities (Lorchaiyakul, 2014) Out of the latter 12 percent, 4 percent had the visit purpose for honeymoon and wedding, another 4 percent for nature tourism, 2 percent for golf and 2 percent for health related tourism (“Research project on Potentials and Market size for niche tourism,” 2013). The details of some important niche tourism were as follows.

Honeymoon and Wedding

Thailand had been a popular destination among wedding and honeymoon couples from North East Asia (44 percent of this niche market), Europe (28 percent) and Southeast Asia (15 percent). In recent years, the country saw increasing numbers of weddings from India. Some Indian wedding groups surpassed 1,500 guests. The wedding tourist tended to travel during Thailand’s peak tourism season. The factors influencing them to visit Thailand were beautiful beaches, luxurious hotels and good weather. Thailand’s hotels in Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Phuket, and Samui had the capability to host wedding of any size, and in any setting or theme.

Health and Wellness

For the medical tourism, the reasons for patients traveling abroad for healthcare were cost savings, shorter wait periods, and treatment that were not available in their own countries. Among the total number of tourists to Thailand, about 2.5 million had already visited for health tourism or medical tourism reasons. However, Thailand faced serious shortages of healthcare professionals. If further promoted, international medical tourism industry would drain personnel resources from hospitals servicing the local populace. Wellness centers, however, did not face this limitation and so offered a full range of services from a clean diet to personalized regenerative and metabolic treatments.

Golf

Thailand was one of the top three golf destinations, attracting about one million golf tourists annually. Thailand’s foreign golf tourism continued to expand. An international golf tourist spent an average of USD 3,300 per trip --- three times higher than an average tourist. These five major golf destinations were their favorites: Bangkok, Phuket, Hua Hin, Pattaya and Chiang Mai (Sullivan, 2011). The majority of these foreign golfers (71 percent) was from North and East Asia, while Europeans accounted for 15 percent (“Research project on Potentials and Market size for niche tourism,” 2016). Golfers’ requirements were beautiful golf courses, 5-star accommodation and facilities, excellent services and good weather.

MICE

MICE tourists were another high-spending potential group. An average MICE tourist spent three times more than a general tourist. The MICE sector accounted for less than 3 percent of the annual international tourist arrivals to Thailand but was expanding. In 2013, the number of this group exceeded one million, of which 72 percent were from Asia. The top five countries from which they came were India, China, Singapore, Japan and Malaysia, but China was the main market, both in terms of the number of visitors (128,437) and spending (USD 360 million). The requirements of this market were similar to that for golfers, i.e., 5-star accommodation and facilities, excellent services and good weather. In addition, they wanted to engage in other activities, including sightseeing and shopping.

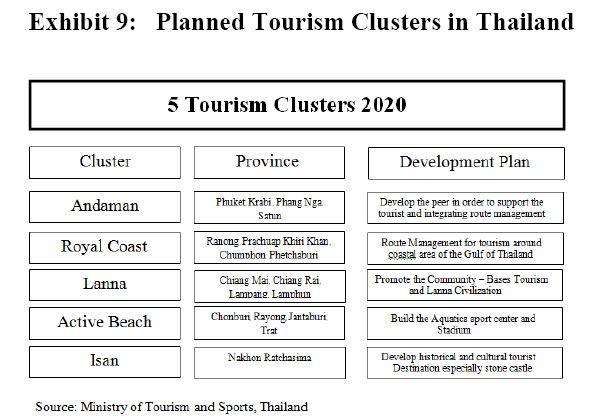

Culture

There was a proposal to form tourism clusters in order to entice foreign tourists to venture beyond typically popular attractions. Each of these clusters was planned for a group of provinces and had distinct objectives. For instance, the northeastern civilization cluster incorporating Nakorn Rachasima, Buriram, Surin, Srisaket, and Ubon Ratchatani provinces aimed to develop tourism relating to local lifestyle and knowledge and linked with neighboring countries (i.e., Laos, Myanmar and South China). Andaman in the lower south would be a gateway to connect and send tourists to other parts of the country (“Kobkarn to focus 2017 tourism strategy on high quality tourism,” 2015). Exhibit 9 shows the clusters of these tourism regions. The success of this cluster depended on the collaboration within each group, e.g., not undercutting prices and developing their manpower, facilities and infrastructure to meet the higher standards of international tourists. Realistically, in the short term, several of the clusters might be more attractive to local tourists than international ones. In fact, Mr. Yuthasak relied on the promotion to Thai tourists to sustain the industry whenever the number of international tourists declined due to negative events such as the deadly bombings attacks across seven southern Thai provinces in last August. (TAT Governor to use big events to stimulate local tourism, 2015)

However, pitching culture as a tourism product could be a sensitive issue as seen in the case of the "Fun to travel in Thailand" music video that was launched in September 2016 for the TAT to persuade Thais to travel domestically, instead of taking a trip abroad. The Ministry of Culture ordered the producer to change the contents they deemed as damaging to the Thai culture. The authority believed that the characters from the Ramakien, the Thai version of the Indian Hindu Ramayana epic, should be reserved in the traditional and classical forms and should not be presented as engaging in popular touristic activities such as serving coconut cream cakes, taking selfies and driving go-carts at popular tourist locations (“Campaign backs use of ogres in tourism fun video,” 2016). Exhibit 10 shows some captures of this advertisement.

Time for Decision

As suggested by the above discussion of the industry, the committee’s challenge was to develop a plan that would not only keep tourist arrival numbers on the upward trend, but do so in a way that would, ideally, yield more tourist revenue per capita; not over-stress the most popular tourist destinations in the nation; facilitate a more equitable distribution of tourist income among the populace; ensure the at the maximum amount of revenue remained within Thailand and not leaked out to the foreign nominees; and, lay the foundation for future offerings that could better differentiate Thailand from its regional competitors all the while avoiding, if possible, the domination of tourist arrivals by any particular demographic group and cultural clashes. Clearly, this was a tall challenge and one made all the more challenging by the many different combinations and permutations into which the strategic options could be arrayed. Doubtlessly, some trade-offs would be required, such as, the types of tourists and the number of tourists that the country can accommodate. The committee believed, however, that it now had a sufficient robust picture of the state of the tourism industry in Thailand to begin to sort through the strategic options in search of the optimal ones.

References

- Activity 1 | The rise of tourism. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from Unesco.org

- ASEAN Tourism Strategic Plan 2011 – 2015. (2012). Retrieved May 14, 2016, fromwww.aseantourism.travel/downloaddoc/doc/2486

- Campaign backs use of ogres in tourism fun video. (2016). Retrieved September 22, 2016, from http://www.bangkokpost.com/news/general/1092248/campaign-backs-use-of-ogres-in-tourism-fun-video

- Chhor H., Dobbs R., Hansen D.H., Thompson F., Shah N., & Streiff L. (2013). Retrieved May 15, 2016, from http://www.mckinsey.com/global-themes/asia-pacific/myanmars-moment

- Chinese tourists are causing chaos at Chiang Mai University in Thailand. (2016, April 18). Retrieved March 16, 2016, from http://www.news.com.au/travel/travel-updates/chinese-tourists-are-causing-chaos-at-chiang-mai-university-in-thailand/story-e6frfq80-1226888976134

- Chong, E. (2016, January 18). A look into tourism in ASEAN, and how we can optimize this sector for growth. Warwick ASEAN Conference. Retrieved from http://warwickaseanconference.com/a-look-into-tourism-in-asean-and-how-we-can-optimize-this-sector-for-growth

- Clausing, J. (2015). Global growth in wellness trips. Retrieved March 23, 2016, from http://www.travelweekly.com/Luxury-Travel/Insights/Growth-in-spa-wellness-travel-trips

- Eco Tourism on The Rise Current situations and trends in tourism. (2015). Retrieved May 18, 2016, from http://secretary.mots.go.th/policy/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=1584

- Eco Tourism on The Rise. (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2016, from http://cccmaldives.com/?page_id=33 Fernquest, J. (2015). Thailand's roads second-deadliest in world, UN agency finds.

- Retrieved May 30, 2016, from http://www.bangkokpost.com/learning/work/738124/thailand-roads-second-deadliest-in-world-un-agency-finds

- Global Trends in Marine and Coastal Tourism. (2016). Retrieved May 24, 2016, fromhttp://www.freenomads.com/blog/?p=1351#sthash.QGBcFgx8.dpbs

- Gray, D. D. (2014). Bad Chinese Tourists Are Earning A Reputation As The New 'Ugly Americans'. Retrieved

- March 20, 2016, from http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2014/04/15/chinese-tourists-ugly-americans_n_5150905.html

- How to Target Chinese Shoppers Abroad. (2016, March 9). Retrieved September 17, 2016, from http://blog.euromonitor.com/2016/03/how-to-target-chinese-shoppers-abroad.html

- Jirarushnirom, J. (2016). What do Thais gain when Chinese tourists visit? Retrieved May 17, 2016, from http://www.posttoday.com/analysis/report/423733

- Kangwanwong, N. (2016, February 22). Authorities alerted as Chinese investors cash in on

- tourism. Retrieved August 7, 2016, from http://www.nationmultimedia.com/business/Authorities-alerted-as-Chinese-investors-cash-in-o-30279812.html

- Kaosa-ard, M. S. (1994). Thailand’s Tourism Industry What do We Gain or Lose? TDRI Quarterly Review, 9(3), September, 23-26.

- Kobkarn to focus 2017 tourism strategy on high quality tourism (2015) Retrieved May 25, 2016, from http://www.mfa.go.th/business/th/news/84/58247- Kobkarn to focus 2017 tourism strategy on high quality tourism.html

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N. (1998). Tourism in Thailand: Patterns, trends and limitations.

- Pacific Tourism Review, 2, 225-238.

- Lin, X. (2015). Top 10 global destinations of Chinese tourists. Retrieved May 28, 2016, from http://www.china.org.cn/top10/2015-10/21/content_36842053.html

- Lorchaiyakul, P. (2014). Research project on ASEAN tourism markets 2014 . Retrieved May 30, 2016, from http://www.etatjournal.com/web/menu-read-web-etatjournal/menu-2014/menu-2014-apr-jun/590-22014-asean

- ‘Lost in Thailand’ film results in tourists from China. (n.d.) Retrieved May 28, 2016, from http://www.samuitimes.com/lost-thailand-film-results-tourists-china/

- Lowe, F. (2006, January 15). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2006/jan/15/travelnews.thailand.theobserver

- Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity, Association of Southeast Asian Nations. (2013). Retrieved March 16, 2016, from ttp://www.mfa.go.th/asean/contents/files/customize-20130130-140932-379647.pdf

- Mendiratta, A. (2015, October). Senior Travellers: Global Tourism’s Silver Lining. Retrieved May 23, 2016, from http://commercial.cnn.com/resources/task/compass/78.pdf

- Mohamed, B. (2016). Strategic Positioning of Malaysia as a Tourism Destination: A Review. Retrieved March 16, 2016, from http://s3.amazonaws.com/za6.nran_storage/www.ttresearch.org/ContentPages/2483313261.pdf

- Muqbil, I. (2013). China is Now Dominant Force in Thai Tourism. Retrieved May 16, 2016, from http://www.lookeastmagazine.com/2013/03/china-is-now-dominant-force-in-thai-tourism/

- Negative Economic Impacts of Tourism. (n.d.). Retrieved March 14, 2016, from http://www.unep.org/resourceefficiency/Business/SectoralActivities/Tourism/FactsandFiguresaboutTourism/Im pactsofTourism/EconomicImpactsofTourism/NegativeEconomicImpactsofTourism/tabid/78784/Default.aspx

- Nikitina, O., & Vorontsova, G. (2015). Aging Population and Tourism: Socially Determined Model of Consumer Behavior in the "Senior Tourism" Segment, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 214, 845-851.

- Olivier. (2015, Aug 24). 7 Key Features of Chinese Tourists. Retrieved May 23, 2016, from http://marketingtochina.com/7-key-features-of-chinese-tourists/

- Ouyyanont, P. (2001). "The Vietnam War and Tourism in Bangkok's Development, 1960-70"Southeast Asian Studies 39 (2), 157–187

- Paris, N. (2014, November 16). Thailand 'most dangerous tourist destination', claims book. Retrieved September 16, 2016, from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/asia/thailand/articles/Thailand-most-dangerous-tourist-destination-claims-book/

- Prayut ordered to hold an urgent meeting on Chinese zero-dollar tours. (2016). Retrieved September 12, 2016, from http://www.thaisohot.com/content/Prayut ordered to hold an urgent meeting on Chinese zero-dollar tours.

- Research project on Potentials and Market size for niche tourism (2013). Retrieved May 25, 2016, from http://www.etatjournal.com/web/menu-download-zone/14-cate-download-zone/cate-dl-executive-summary/542-201310-dl-golf-honeymoon-wedding

- Richard, G. (2011). Tourism Trends: Tourism, Culture and Cultural Routes. Retrieved May 23, 2016, from http://www.academia.edu/1473475/Tourism_trends_Tourism_culture_and_cultural_routes

- Rothwell, J. & Palazzo, C. (2016). Four killed and at least 20 injured in string of explosions in southern Thailand. Retrieved September 16, 2016, from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/08/11/one-dead-and-ten-injured-Sports after-bombs-hit-thailand-resort-town-of/

- Schmid, T. (2012, October 1). The Darker Side of Tropical Bliss: Foreign Mafia in Thailand.

- Retrieved March 16, 2016, from http://www.thailawforum.com/the-darker-side-of-tropical-bliss-foreign-mafia-in-thailand/

- Sports Tourism: Key drivers of Tourism (2014). Voyager’s World. Retrieved May 20, 2016, from http://w2.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Sports-Tourism-story.pdf

- Statistics and Facts on the Global Tourism Industry. (2016, March 3). Retrieved from http://www.statista.com/topics/962/global-tourism/

- Study on supportive way of tourism in foreign tourists who had repeated trips. (n.d.). Retrieved August 26, 2016, from http://www.research.rmutt.ac.th/?p=8035

- Sullivan, B. (2011, September 21). Thailand Golf Tourism May Reach $US 2 Billion in. Retrieved May 25, 2016, from http://www.thailand-business-news.com/tourism/31718-thailand-golf-tourism-may-reach-us-2-billion-in-2012.html

- TAT Governor to use big events to stimulate local tourism. (2015, September 4). Prachachat online news. Retrieved November 12, 2016, from http://www.prachachat.net/news_detail.php?newsid=1441266019

- TAT to collaborate with CLMVT countries to stimulate tourism. (2016, June 9). Thansettakij Multimedia. Retrieved November 12, 2016, from http://www.thansettakij.com/2016/06/09/60881

- Thai Officials to investigate more than 50% Rise in Tourist Deaths in Thailand. (n.d.). Retrieved

- May 25, 2016, from http://www.samuitimes.com/thai-officials-to-investigate-more-than-50-rise-in-tourist-deaths-in-thailand/

- The Global Wellness Tourism Economy 2013. (2013). Retrieved May 23, 2016, fromhttp://www.retreatnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/2013_wellness_tourism_economy_exec_sum.pdf

- Thongrod, W. (n.d.). Thai tour guides claim foreigner stealing their jobs, ruining. Retrieved March 16, 2016, from http://www.pattayamail.com/localnews/thai-tour-guides-claim-foreigner-stealing-their-jobs-ruining-country-33619#sthash.U0Cvc4TG.dpuf

- Tour agents urge concert measures on zero-dollar operations. (2016, September 16). Retrieved

- September 20, 2016, from http://www.bangkokpost.com/business/tourism-and-transport/1086164/tour-agents-urge-concrete-measures-on-zero-dollar-operations

- Tourism Industry (Social Science). (2016). Retrieved March 16, 2016, from http://what-when-how.com/social-sciences/tourism-industry-social-science/

- Tourism Statistics Thailand 2000-2016. (2016) Retrieved May 16, 2016, from http://www.thaiwebsites.com/tourism.asp

- Two Trillion baht revenue in tourism and marketing missions (2013). Retrieved March 18, 2016, from http://www.tatreviewmagazine.com/mobile/index.php/menu-read-tat/menu-2013/menu-2013-jul-sep/127-32556-income-market

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2014 Edition. (2015). Madrid: UN World Tourism Organization(UNWTO), 2014 Edition Retrieved March 15, 2016

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2015 Edition. (2016). Retrieved March 19, 2016, from http://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284416899

- Vision for Thai tourism 2558-2560 (2016).Retrieved May 18, 2016, fromhttp://www.mots.go.th/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=7114

- Vojvodic, K. (2015, April 17). Understanding the Senior Travel Market: A Review. 3rd International Scientific Conference Tourism in Southern and Eastern Europe 2015. Retrieved May 23, 2016, from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2637744

- Wattanakuljarus, A., & Coxhead, I. (2008). Is tourism-based development good for the poor?: A general equilibrium analysis for Thailand? Policy Modeling, 30(6), 929-955.

- Wong Y.H, & Choong D. (2015) Retrieved March 31, 2016, from http://newsroom.mastercard.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/MasterCard-GDCI-2015-Final-Report1.pdf

- World Population Ageing 2013. (2013). Retrieved May 23, 2016, fromhttp://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2013.pdf

- Zero-dollar tour crackdown gains momentum. (2016, August 16). Retrieved September 2, 2016, from http://www.bangkokpost.com/business/tourism-and-transport/1072216/zero-dollar-tour-crackdown-gains-momentum /1072216