Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 5

The Entrepreneurial Intention of Graduate Students: Challenges and Prospects

Bechir Fridhi, College of Business Administration, Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia

Muhamed Alwheeb, College of Business Administration, Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

This research aims to study not only the intention to create a business, but also attitudes towards starting a business and perceptions of social norms and their impact on the ability to conduct an entrepreneurial process. To do this, we are conducting a study on 50 graduates of College of Business Administration, Majmaah University. Our results reveal the importance of attitudes associated with behavior in entrepreneurial intent. Entrepreneurial culture plays a very important role. What then can be the impact of social norms on entrepreneurial intention? In our results, we found that only the influence of classmates' intentions is significant. Financial constraints, the information that can be conveyed as well as training in starting a business, in other words everything related to perceptions of behavioral control, have an insignificant effect on intention. In this sense can we affirm that the entrepreneurial training followed by the student could be added to his social reality and, in fact, influence the choice of the student's future profession, as long as this training can be integrated in new models, new attitudes which are likely to modify the behavior of individuals?

Keywords

Accounting Organization, Banking Operations, Management Reporting, Accounting Policy, Information Base.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a critical factor in society, and enjoys particular interest from economists, sociologists and policy makers. This interest is undoubtedly due to the place of business creation in economic and social development, the increase in production and income, the reduction of unemployment, the diversification of industry, the promotion of innovation, etc. (Schumpeter, 1935; OECD, 1998; Reynolds, 1994, 2001; Rasmussen & Sorheim, 2006; Minniti & Lévesque, 2008; M.Azis et al. 2018; Fridhi, 2020). Consequently, studying entrepreneurial intentions gives us an idea of the behaviors leading to the creation of a business.

Entrepreneurial intention is the first act in the entrepreneurial process. It sums up a person's desire to create their own business, and can be explained by the individual characteristics of the potential entrepreneur, by his environmental background as well as by his cultural specificities.

As far as we are concerned, we have focused on entrepreneurial intention in the student population which we have approached in a comprehensive manner.

The student, before indicating his intention to create a business, is above all the image of a social, economic and political reality; the family being the student's first social experience. It determines his behavior and transmits to him the values that we would like him to share. The entrepreneur is far from being someone who goes alone and who relies only on his own means to carry out his project. In this sense, Berglann (2017); Krueger & Casrud (1993) argue that the entourage of the project promoter must be favorable to him. This entourage must have the necessary capacities or resources for the project to be successful. According to Granovetter (1995), human behavior cannot be explained by only referring to individual motives; it is shaped and constrained by the structure of social relations in which every actor is registered. Focusing on a single entrepreneur leads to neglecting the reality of business creation, which often corresponds to a collective approach. For Dubini & Aldrich (1991), starting a business is a fundamentally relational activity. Family provides emotional comfort in addition to moral support, while friends with experience in the field provide advice, encouragement and rekindle the entrepreneur's enthusiasm.

The relational network is only one aspect of the factors that can stimulate the entrepreneurial intention of the individual. A state of mind and a dynamic of action of the individual are necessary to achieve entrepreneurial achievement; consequently, entrepreneurship would also be a dynamic of action and a state of mind that can be acquired through training, awareness of situations, support measures, or even through specific techniques and tools (Von Graevenitza, 2015); Hence the importance of the education system, whose mission is to raise awareness, prepare and train for entrepreneurship. For Rasmussen & Sorheim (2016), teaching entrepreneurship in schools and universities can modify attitudes, change the behaviors and beliefs of young students about entrepreneurship, and facilitate their assimilation and integration accessibility to the entrepreneurial phenomenon. Saporta & Verstraete (2010) argue that entrepreneurship education can shape student cognition by promoting the combination of three irreducible and inseparable dimensions: thinking, reflexivity and learning.

The fact remains that the entrepreneurial act is still a very marginal professional process for students. However, with the programs implemented, it is interesting to look at the entrepreneurial intention of the beneficiaries of this training, even if at this stage, it remains a simple professional intention. This will allow us to easily get out of the debate on intention and entrepreneurial acts. Indeed, intention is not always the act, nor is it a prerequisite for this action. How then to define the term "intention" when it comes to entrepreneurship? What factors are likely to accentuate this intention?

It is around these questions that our issue revolves, to which we wanted to give operational scope.

We sought to circumscribe the problems of temporality and validity posed by the study of entrepreneurial intention, from a survey carried out during the 2019/2020 academic year, on a sample of young graduates from College of Business Administration, Majmaah University. The choice of the university institution is not accidental. We have, deliberately, chosen to analyze the behavior of students from this establishment who are, from our point of view, more likely to have the intention of creating their own businesses and who have pursued a suitable university course for the creation business.

After a foray into the field of entrepreneurship which offers a theoretical grounding through the examination of writings on entrepreneurial culture and intention, we will try to present the methodological framework and our model of investigation to, finally, present and discuss the results we have achieved.

Research and Methodos

Entrepreneurial Culture

Every individual belongs to a cultural entity, with which he shares norms and a system of values. Culture would then bring together all the knowledge acquired in the group as well as the customs and habits acquired through experience within the group (Léger-Jarniou, 2018). According to Petit Larousse (1980), it represents all the social structures and collective behaviors characterizing a society, while for Hofstadter (1980), culture is a collective mental programming specific to a group of individuals. Léger-Jarniou (2018), for his part, maintains that the notion of entrepreneurial culture refers to the broader notion of culture and mobilizes entrepreneurship as a process of value creation and an act of developing the entrepreneurial spirit, and this, whatever the situation. These authors argue that entrepreneurial culture cannot be studied without making reference to the pedagogy that allows it to be developed. Heinonen & Poikkijoki (2016) insisted on the need for a new model of education that emphasizes experimentation, action or teaching by doing as a laudable pedagogy. The development of behaviors and attitudes, which are the heart of entrepreneurship emphasizes the learning process and, of course, the learning environment which should encourage them to become actively involved. This involves teaching that is action-oriented and encourages learning through experimentation. For Léger-Jarniou (2018), changing attitudes and behaviors requires specific pedagogy: classical pedagogy allows knowledge to be provided, while practice, simulation and confrontation with problems bring experience, which will, over time, modify aptitudes, attitudes and personality. He argues that assessment is a key part of the learning process. This must be, according to Félix Oscar (2020), the act by which a value judgment is formulated on a given object by means of a comparison between two series of data which are put in relation: data which are of the order of the fact and which concern the real object to be evaluated, and of the data of the order of the ideal and which concerns expectations, intentions or projects applying to the same object.

In any case, we can identify in the literature (Léger-Jarniou, 2018; Arenius & Minniti, 2015) that entrepreneurial culture is linked to innovation, creativity, attitude towards risk-taking, independence, perception of opportunities in the environment, ambition, originality, long-term projection, ability to solve problems.

Thus, in terms of entrepreneurial culture, it is clear that there is a necessary constructivist and playful pedagogy. As a result, two models coexist in educational science: the behavioral and the constructivist, which offer, according to Hamilton & Hitz (2006), quite different solutions for education and training. For Léger-Jarniou (2018), the traditional behavioral model focuses on the acquisition of information that fits into the knowledge structure of the learner until new information appears that updates the previous one; whereas the constructivist model assumes that learning is contextual and undergoes many influences. The fact remains that entrepreneurial pedagogy has become more constructivist, as it focuses on expert options, by teaching difficult and counterfactual thoughts (Saks & Gaglio, 2014), by asking students to be self-directed learners, and forcing them to reflect on their learning of knowledge (Morse & Mitchell, 2015).

The Conceptual Framework of Entrepreneurial Intention

In the literature, we find several models of intention such as that of the theory of planned behavior of Ajzen (1991) in social psychology. Regarding the entrepreneurial act, we have the model of Shapero & Sokol (1982). This model was taken up and presented by Tounès (2006) and becomes a model of intention applied to entrepreneurship.

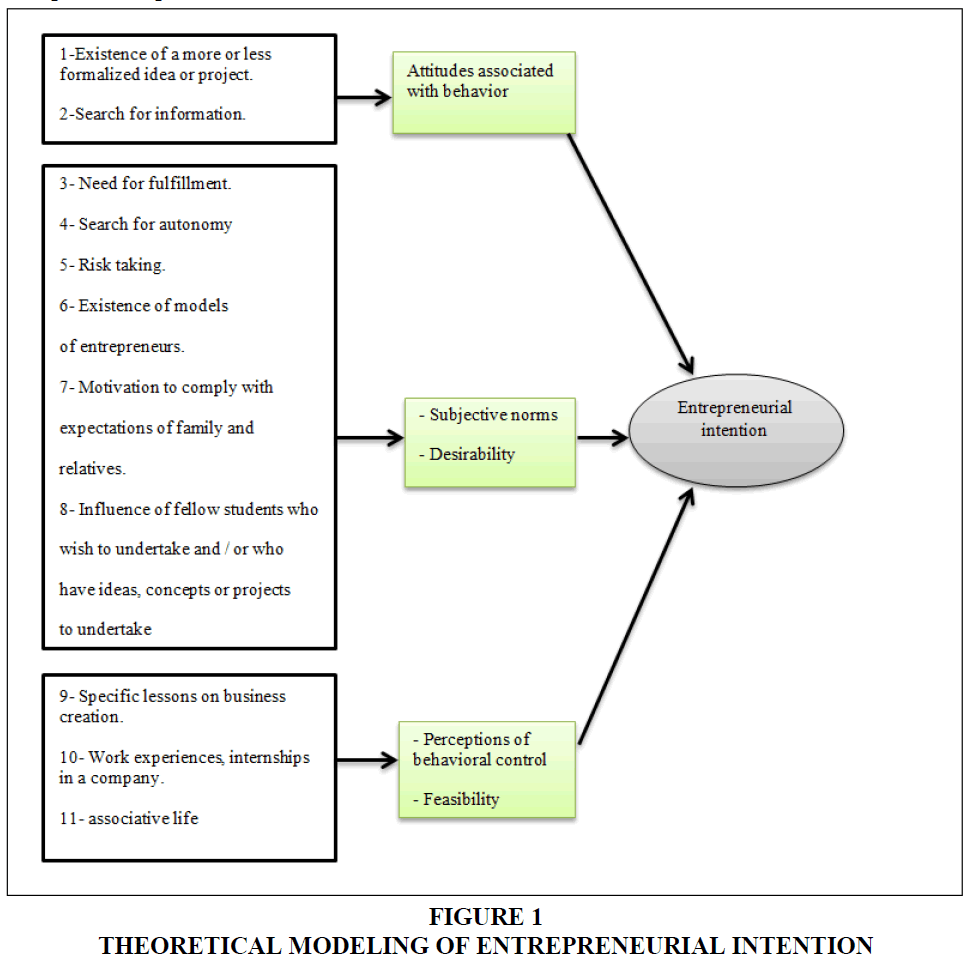

The Figure 1 below is a representation of the operation of intention models applied to entrepreneurship.

In our approach, and to clarify our items, we used this model which has been widely validated by various studies for the act of creating a business (Krueger & Carsrud, 1993; Autio et al., 1997; Tounès, 2003, 2006; Fayolle et al., 2006; Klapper & Léger-Jarniou, 2006; Krueger & al. 2010; Virginia Barba-Sánchez, 2019; Sunday Olawale Olaniran, 2020). Some of these authors have more specifically targeted a student population.

However, it is up to us to make it clear that, except in routine acts, intention always precedes action. Thus, intentional behavior can be predicted by the intention to have a given behavior. This is how the intention to start a business will be stronger when the action is seen as feasible and desirable. In the work of Shapero & Sokol (1982), desirability reflects the degree of attraction that an individual perceives in starting a business. Whereas feasibility refers to an individual's awareness of the degree to which they think they can successfully start a business. Ajzen (1991) talks about perceived control, he talks about the more or less favourable attitude a person has when faced with a choice.

Desirability and feasibility are therefore two very close concepts. They are explained by the beliefs that the person has about the world around him. Thus, according to the proposals of Ajzen (1991), it appears that the attitude of a student towards the creation of a company is based on his professional values and his vision of entrepreneurship. As for feasibility, it would depend on the student's confidence in his ability to carry out tasks deemed critical for the success of an entrepreneurial process.

Ultimately, we can note that the entrepreneurial intention is determined by the desirability of this act and by the perceived capacity, two dimensions which are themselves a reflection of the beliefs of the students. To fully understand the structuring of the mindset of students, then, do we need to study these beliefs closely?

However, it must be noted that, in this model, there is a strong underestimation of the place of opportunities in the entrepreneurial act which, sometimes, exceed intentions.

Remember that our study does not focus on the entrepreneurial action decision process, but on the intentions of the student population. For Tounès (2007), intention is the result of a long process dictated by the actions and motivations of the students, the existence of entrepreneurial models, the expectations of the family or the immediate entourage, the culture entrepreneurship of the establishment and perceptions of the feasibility of the act of entrepreneurship; entrepreneurial training not having a very significant effect on the evolution of entrepreneurial intention (Boissin & Emin, 2016). Kolvereid (2006), studying a sample of about 100 Norwegian business school students, shows that intention to start a business is significantly correlated with behavioral attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioural control. The latter two have more effect on intention than the former. Individual socio-demographic variables do not have a significant impact on intention, although they are correlated with social norms and perceived control.

Krueger (2010) applied Ajzen's model to the career choice of some 100 former business school students in the United States. Analyzing perceived feasibility and the attitudes that significantly determine intention, they came to the same results as Kolvereid's, namely that feasibility has more effect on intention than behavioral attitudes. Instead, they found that social norms do not have a significant impact, unlike the results found by Kolvereid (2006). Kennedy et al. (2013) show, from a sample of 1000 Australian students, that Ajzen's intention model works well with an effect of three main types of variables.

Emin (2013), on a study of 744 public researchers working in the Paris region, demonstrated that the intention model can be useful in predicting intentions to start a business in academia. On the same line of thought, the author argues that while the desire to start a business and the perceived feasibility significantly contribute to the prediction of the intention to create a business, the influence of the perceived social norm is not significant. Beliefs about the important role of professionals also do not have a direct effect on the intention to start a business. However, the social norm and the perceived professional role have an indirect impact via their influence on the desire to create. His study reveals another interesting result: the existence of a preponderant weight of the desire to act in the prediction of intention.

All of these results confirm the interest of the model of planned behavior for the study of business creation. Also, in our approach, we have used these three main determinants of intention: behavioral attitudes, social norms and perceived control.

Building the Database

We aim to verify the results obtained from a sample of graduates of the College of Business Administration, at the end of the 2019/2020 academic year. Our sample responded to a self-administered questionnaire, that is, distributed when they obtained their certificates of achievement by the administration, and administered in Arabic.

The sample consists of 50 students who obtained their diplomas for the year 2019/2020, of which 70.4% are male.

Data processing was performed with SPSS data analysis software.

Measure of Intention

Following the work of Ajzen & Fishbein (1980), intention was measured taking into account the professional alternative: salaried employment / entrepreneurship.

Three items were established: (1) the probability that you create your business is very high, (2) the probability that you pursue a career as an employee is very high and (3) whether you have to choose between starting your business and being an employee, you would certainly prefer to start your own business. As a preamble to the questionnaire, it was specified that the student should take "business creation" in a broad sense.

Declarations of the level of agreement of young graduates were entered with the following measures: from 1 "total disagreement" to 7 "total agreement".

To maintain the internal consistency of the items forming the components highlighted, we retain, in our analysis, only items 1 and 3 (Cronbach's alpha> 0.5 = 0.813).

A principal component analysis was performed to factor these two items (Bartlet's significance <0.001). We obtained a single axis called "intention" whose eigenvalue is greater than 1; it explains 84.5% of the initial total variance.

Measurement and Analysis of the Variables that Explain the Entrepreneurial Intention

The variables involved in entrepreneurial intention are many, and we have chosen a number that are best suited to address our concern. This choice is certainly not objective. However, our problematic leads us to retain the hypotheses of Tounès (2006) which seem to us to be the most explanatory of the entrepreneurial intention of a student population evolving in a specific context, namely the follow-up of training in entrepreneurship.

12 items describe the various characteristics of entrepreneurial intention. 2 items state the attitudes associated with the behavior, 6 items measure subjective or social norms and 4 items measure perceptions of behavioral control. The student had to respond on his perception of these items both for the quality of his future professional life and for the quality of life resulting from the career of an entrepreneur.

Almost all of the items were entered on 7point in Likert scales.

We apply the method of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the items used for each of the 3 elements. The Table 1 below denotes the following results:

| Table 1 Explanatory Factors for Entrepreneurial Intention | ||||

| For all three PCAs, (Bartlett's significance <0.001) | PCA-1 | PCA-2 | PCA-3 | |

| Attitudes Associated with behavior | Subjective or social norms | Perception of behavioral control | ||

| Items | Factor1 | Factor2 | Factor3 | Factor4 |

| 1-Existence of a more or less formalized idea or project. | 0.859 | |||

| 2-Search for information. | 0.859 | |||

| 3- Need for fulfillment of entrepreneurs. | 0.739 | |||

| 4- Search for autonomy | 0.739 | |||

| 5- Risk taking. | 0.66 | -0.701 | ||

| 6- Existence of models | 0.668 | |||

| 7- Motivation to comply with expectations of family and relatives. | 0.599 | 0.75 | ||

| 8- Influence of fellow students who wish to undertake and / or who have ideas, concepts or projects to undertake | ||||

| 9- Specific lessons on business creation. | 0.606 | |||

| 10- Work experiences, internships in a company. | 0.835 | |||

| 11- associative life | 0.66 | |||

| 12- Accessibility of resources: financial, information and advice | 0.687 | |||

| Own values | 1.48 | 2.37 | 1.44 | 1.97 |

| Total variance explained | 74.42% | 63.54% | 49.29% | |

| Cronbach's alpha | 0.656 | 0.667 | 0.631 | |

In all three cases, the reliability analysis of the items used reached a Cronbach's alpha> 0.5.

We remove the items whose correlation with the axes is too weak (<0.5).

We obtain four explanatory factors for entrepreneurial intention. The factor 1 defines attitudes associated with student behavior, the factor 2 and the factor 3 describe subjective or social norms, and the factor 4 describes perceptions of behavioral control.

Explanatory Model of Entrepreneurial Intention

By performing a multiple linear regression, with the four factors combining desirability and feasibility, we were able to better explain the entrepreneurial intention of the students consulted (Table 2).

| Table 2 Regression Results | |||

| Dependent variable: intention | Beta (t) | Fisher() | |

| Foctor1 | 0.267 (1.79)*** | ||

| Foctor2 | 0.029 (0.15)* | 0.229 | 3.268** |

| Foctor3 | 0.272 (2.04)** | ||

| Foctor4 | 0.192 (1.11)* | ||

| Significance threshold: *** (p <0.01), ** (p <0.05), * (p <0.1) | |||

The factors 1 and 3 are the determining variables of intention; their coefficients are positive and significant. The low coefficient of determination of entrepreneurial intention, i.e. 22.9%, suggests that there are other explanatory factors of the intention that are not incorporated in our approach, such as the gender of the interviewee or the employment situation at the time of the survey.

The fact remains that the impact of factor 1 on intention is positive and significant. Indeed, entrepreneurial intention is increased by improving attitudes associated with student behavior. We argue, in fact, that practice and problem-solving provide the experience necessary to modify the skills of the potential entrepreneur and to reorient his attitudes and personality. This corroborates with the conclusions of Léger-Jarniou (2008) for whom classical pedagogy does, of course, provide knowledge, but to change attitudes and behavior, a particular pedagogy must be applied.

The insignificant impact of factor 2 implies that social norms do not sensitize entrepreneurial intention. This result mentions that the impact of entrepreneurial culture among new graduates in our sample is low; entrepreneurial culture being that which highlights the characteristics of the person who stimulates his desire to be entrepreneurial and which accentuates his individualism, his marginality and his need to fulfill himself and to take risks (Johannisson, 1984). Moreover, this result is in contrast with several studies (Van Auken, 2016; Gasse 2016; Shivani, 2016) which show that individuals who have parents, business owners, or who have a activity of self-employed person, would be more inclined to create companies or, at least, to present the intention to do so. According to Fridhi (2020), the family, in the Saudian context, plays two important roles in the accomplishment of the entrepreneurial activity of the creator: the first is financial, and the second is comfort. It intervenes to minimize the cost of creation. Indeed, suppliers, having family ties with the creator, can grant him payment facilities. The loans granted by the parents are a good comfort to the creator. This seems obvious to the extent that starting a business is an adventure that the individual cannot lead alone, although he is the main actor. His relational network is as important as his personal effort. Her relational network, whether it is made up of family, professional or social relationships, enables her to obtain the necessary information, possibly the financial and administrative assistance necessary to complete her project in a timely manner. For Salhi & Jamali (2018), interpersonal relationships allow the entrepreneur to overcome the difficulties of creation, to extend his field of action, to save time and to access resources and opportunities otherwise inaccessible.

The factor 3 positively and significantly stimulates entrepreneurial intention. This result shows that the influence groups of the creator's private entourage traditionally correspond to the groups of friends and ethnic groups which, in some countries, are associated with entrepreneurial activity (Shapero & Sokol, 1982). Indeed, very often the intention to undertake is suggested by friends who are ready to join forces to create their own jobs.

The non-significance of factor 4 shows that perceptions of behavioral control have no effect on entrepreneurial intention. This result supports that the educational path, the entrepreneurial experiences (internships, odd jobs, associative life) and the accessibility to resources (financial, information and advice) do not stimulate the intention of young graduates to create their own businesses. To wonder if education and training can have any impact on entrepreneurial intention, the results we have achieved show that this education factor as well as that of funding means are not likely to influence entrepreneurial intention. It is therefore necessary to wonder why commit, at the level of schools and universities, so many means for the learning of entrepreneurship, when the expected result does not go in the direction of stimulation, nor of entrepreneurial intention, or the creation of a business proper.

Conclusion

Business creation is an important vector for the creation of employment and wealth. This business creation is preceded by the intention to create. Can we then separate the intention to undertake from the act itself? Admittedly, all the intentions are not realized; however, they represent the best preacher of entrepreneurship. In this approach, we have attempted to explain the intention to be an entrepreneur through different factors, mainly factors related to attitudes associated with behavior, social norms and perceptions of behavioral control.

We have sought to provide some answers to the question of how these factors can influence the intention to start one's own business. We targeted the student community, which seemed to us the environment capable of being sensitized on the issue, given the training and acquired skills that it received.

Our results only highlight the importance of behavioral attitudes in entrepreneurial intention. Social norms (mainly defined by factor 2) and behavioral perceptions remain insignificant. The magnitude of the impact of factor 3 on intention reveals that intention increases, significantly, with influence by fellow students who wish to undertake. Indeed, this result shows the importance of entrepreneurial training in universities. Today, with the increase in graduate unemployment, university institutions are called upon to train and educate high school graduates, through various educational processes, to the creation of their own businesses. Teaching entrepreneurship is an educational pedagogy that is not only widespread in management schools (it is part of training in management sciences), but in addition, the majority of schools all seek to develop their own training in entrepreneurship (Solomon & al. 2012; Katz, 2013). These teachings impart knowledge about the values, attitudes and motivations of entrepreneurs and the reasons for doing business.

Indeed, they develop the entrepreneurial culture of a nation in the face of increasing complexity, the phenomenon of globalization and the difficulty of anticipating markets whatever they may be. Entrepreneurship education and training meet the objectives of success for our economies at the economic, political, social and technological levels and encourage individuals to take conscious risks for the development of new organizations creating added value.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the deanship of scientific research, Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia, for their support and encouragement; also the authors would like express our deep thanks to our university, Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211.

- Aldrich H., & Fiol C.M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645-671.

- Barba-Sánchez, V., Ortíz-García, P., & Olaz-Capitán, A. (2019). Entrepreneurship and disability: Methodological aspects and measurement instrument. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 22(S2).

- Bassem. S., & Mehdi, J. (2018). Entrepreneurship intention scoring. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21(1).

- Emin, S. (20 16 ). The determining factors of business creation by public researchers: Application of intention models. Revue de l'Entrepreneuriat, 3(1).

- Fayolle A., Gailly, B., & Lassas-Clerc, N. (2006). Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education programmes: a new methodology. Journal of European Industrial Training, 30,701-720.

- Fridhi, B. (2020). The entrepreneurial intensions of Saudi Students under the kingdom's vision 2030. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(S1).

- Hamilton D. & Hitz R. ( 200 6). Reflections on a constructivist approach to teaching. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 17(1), 15-25.

- Katz, J.A. (20 1 3). The chronology and intellectual trajectory of American entrepreneurship education 1876–1999. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 283-300.

- Kennedy, J., Drennen Dr, J., Renfrow Dr, P., & Watson B. (20 1 3). Situational factors and entrepreneurial intentions. 16th Annual Conference of Small Enterprise Association of Austrian and New Zealand, vol. 28, September – October.

- Krueger, N., Reilly, M.D., & Carasrud, A.L. (20 1 0). Competing models of entrepreneurship intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411-432.

- Leger-Jarinou. C. (20 1 8). Developing an entrepreneurial culture among young people. Revue française de gestion.

- Olaniran, S.O. (2020). Are education graduates only trained to teach? A review of entrepreneurship opportunities in the education sector. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(S1).

- Schumpeter, J.A. (1934). Theory of economic development. Research on profit, credit, interest and the business cycle, Dolloz, 1912.

- Shapero, A., & Sokol L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship, Englewood Cliffs : Prentice Hall, chapyer4, 72-90.

- Socorro Márquez, F.O., & Reyes Ortiz, G.E. (2020). Entrepreneurship and micro-enterprise: A theoretical approach to its differences. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(S1).

- Tounes, A. (2007). A theoretical modeling of entrepreneurial intention. Proceedings of the VIIth Scientific Days of the Entrepreneriat Network.

- Tounes, A. (2006). The entrepreneurial intention of students: the French case ”, Revue des Sciences de gestion, Direction et Gestion, May/June.