Research Article: 2021 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

The Entrepreneurial Path to Success for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) in the Tourism Sector Using Intuitive Competitive Intelligence

Bulelwa Nguza-Mduba, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Emmanuel Mutambara, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Abstract

The aim of the study was to examine whether small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the tourism sector in the Eastern Cape Province (ECP) employed intuitive competitive intelligence (ICI) to succeed in the business world. The study objectives were to determine practices that assisted SMTEs in the ECP, to succeed in the business world; ascertain how SMTEs enterprises’ characteristics in the ECP affected their ICI; investigate whether external forces influenced the ICI practices of SMTEs in the province; identify a framework that could be developed to enhance understanding and research on ICI practices for SMTEs’ entrepreneurial success in the ECP, to mention a few. The study employed a quantitative design comprising of 100 business owners, 30 public body officials in the respective municipalities and 99 tourists, totalling 299 participants. For SMTEs sampling was done through random sampling, for public body officials, purposive sampling was used, while for tourists, convenience sampling was employed. The empirical data was gathered using a semi-structured questionnaire that was distributed and administered to the aforementioned participant groups. The quantitative data analysis was done using the SPSS, in which descriptive statistics and regression analysis (multiple and logistic) were undertaken. The findings confirmed that SMTEs are faced with challenges that affect their sustainability and entrepreneurial success. Results showed that tourists indicated their perceptions of the small tourism businesses in terms of the poor infrastructure to access the accommodation facilities, the location and condition of the facilities and the service provided. It also became clear that public bodies did understand tourism policies, though they did not have a reliable database of Small and Medium-Sized Tourism Enterprises (SMTEs) to provide them with support. In addition, it was apparent that they did not provide them with all types of support, more especially those that were established in the rural areas. The recommendations for future studies mention that the study should be replicated in other provinces, more especially in the urban areas for comparison purposes of the application of intuitive competitive intelligence practices for entrepreneurial success for SMTEs. A study of the performance of district and local municipalities should be undertaken to determine the causes of the problems that affect tourism activities and to try to solve them to enhance the performance of both small and big businesses. In addition, to assist by developing strategies to attract tourists to the ECP. As well, determining how the combination of external and internal intuitive competitive intelligence factors influence the corporate innovativeness, operations and performance of small and medium-sized tourism enterprises.

Keywords:

Intuition, Competitive Intelligence, Intuitive Competitive Intelligence, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises, Entrepreneurial Success, Tourism Sector, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

Introduction

The study sought to establish if Small Tourism Enterprises (SMTEs) in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa apply intuitive competitive intelligence (ICI) as tool to enhance business competitiveness and sustainability in the business world. The Eastern Cape Province was selected because of its natural vegetation and beaches that attract a significant number of tourists to the province. There are numerous views on the descriptions of competitive intelligence, as there are practitioners in the field (Miller and Layton, 2001: 110; Tarraf and Molz, 2006: 5; Lamb, et al., 2011: 44-45). Franco, Magrinho and Silva (2011: 336) view competitive intelligence as gathering and assessing economic data with the aim of utilising it for improving business operations immediately or in future. Consequently, through research, analysis of data as well as decision-making have to be emphasised to enable competitive intelligence practices to be useful for purposes for which they are meant (Pellissier and Nenzhelele, 2013a; Fakir, 2017; Calof, 2017; Tahmasebifard and Wright, 2018; Asghari, et al. 2019). Intrestingly these authors tend to agree that competitive intelligence assists managers to identify opportunities and threats in the market environment for different purposes.

The PESTEL Model analyses macro environmental factors that are political, economic, social, technological, ecological and legal aspects that are external to business and cannot be controlled, but they influence business either positively or negatively. Porter’s Five Forces Model of Competition, on the other hand, looks at threats posed by buyers, suppliers, rivals, substitute products or services and potential entrants, which either way affect the competitive environment as business depends upon them for survival (Porter, 1980; Porter, 1990; Du Plessis, et al., 2012: 158-159; All Answers Ltd.., 2018). Another commonly used model is the SWOT Analysis which compares and aligns the strengths and weaknesses of a business with external opportunities and threats that are found in a competitive environment (Bose, 2008; Gaspareniene, Remeikiene and Galdelys, 2013; Coca-Cola Ltd.., 2017). Benchmarking, on the other hand, involves scanning of the environment to identify companies that excel in the competitive world and copying their best practices. Another model is that of the Competitive Intelligence Cycle which is designed to determine the steps involved in collecting, analysing and interpreting data to form intelligence that will boost business operations (Louw and Venter, 2013; Asghari, et al., 2019; Bhosale and Patil, 2019; Cavallo, et al., 2020). These various models and theories assist big and small businesses to identify the actions of competitors, their strengths and weaknesses, their strategic marketing plans, research activities and other useful information, but they do not make them successful and sustainable (Cant, et al., 2006; Adidam, Banerjee and Shukla, 2012).

Having mentioned competitive intelligence models and theories, it is worth comparing them to identify the gaps. All of the models of competitive intelligence mentioned above have a common theme or aspect of looking at the dynamic factors affecting a business or organisation in the competitive environment in various ways. They are easy to use, even in other countries, in both big and small enterprises for intelligence management. The SWOT Analysis Theory, on one hand, just gives a list of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats and does not realise that internal and external factors in the business environment are vigorously changing and require managers to apply intuition in decision making when representing the business (Erasmus and Strydom, 2013).

As far as PESTEL Analysis Theory is concerned, it poses challenges, as macro-environmental factors cannot be controlled by a business enterprise. It forces businesses to engage in activities that will suit active developments in a competitive environment. This model needs to be complimented by others. Furthermore, tourism businesses that operate nationally and internationally find it very difficult to apply it since they have to understand markets, competitors, consumers, technology, the economy, culture, laws, and the competitiveness of other provinces and countries. Porter’s Five Forces Model of Competition, on the other hand, is commonly used but it only serves as a starting point for a more robust assessment of a firm’s performance that must be further analysed by other relevant tools (Kompyte, 2018).

Benchmarking is another model that has been used to assist big and small businesses to improve on their operations by comparing themselves with industry leaders, with the purpose of copying best practices from their rivals. However, Benchmarking is short-lived and does not foresee what will happen in the future. The types of Competitive Intelligence Models outlined above can be useful for SA’s SMMEs. The main challenge is that they cannot be used alone, as they need to complement each other. Furthermore, although they are relevant, small tourism businesses may not be aware of them. This then implies that small tourism businesses need to use their intuition for critical thinking in making informed decisions pertaining to dynamic trends in the business environment. The envisaged Theoretical Framework of ICI will try to include these aspects and modify them to suit small tourism businesses in South Africa.

The ICI Framework is one that can assist small tourism businesses to be successful and be sustainable in the market environment. Moreover, it is widely known that small businesses have neither capacity nor wherewithal to organise this function. Yet competitive advantage lies at heart of a small business’s existence. It is thus speculated that successful businesses (existing or aspirational) fulfil the function, if not formally, then intuitively (Bushe, 2019). Therefore, the path to the entrepreneurial success of small and medium-sized enterprises depends on their application of ICI practices.

Kulkarni, Robles-Flores and Popovic (2017) see ICI as application of competitive intelligence provided intuitively by entrepreneurs. Intuition may be ascertained as ability to understand truth through perceiving it without necessarily having proof (Kiel, 2019; Constantiou, Shollo and Vendelo, 2019). Intuition may further be regarded as act of making decisions without use of rational processes and immediate cognition. Decision-making using intuition involves a sense of abstract thinking that may be an impression (Chaston, 2009; Bocco and Merunka, 2013). Intuition is mostly used when managers have to make quick decisions about business activities without being rational. It has been widely used in all the various economic sectors and disciplines such as business, industry, education, agriculture, medicine, engineering, psychology, marketing, law, social sciences and humanities (Deltl, 2013; Fakir, 2017; Teece, 2018; Cavallo, et al., 2020).

Sadler-Smith (2016) sees entrepreneurial intuition as the charged acknowledgment and assessment of a business opportunity emerging because of automatic, fast, non-cognisant and associative processing. Entrepreneurs should be able to apply their intuitive intelligence and experiences on how to respond to market changes in a competitive environment. Aujirapongpan, Jintanee ru-zhe and Jutidharabongse (2020) aver that to remain competitive, associations are being challenged to accumulate tremendous measures of information created from day-to-day activities and client interactions. Managers have moved from settling on decisions that are upheld by data frameworks to using intuition to make decisions that are driven by proof from information.

It is worth explaining the entrepreneurial path to success for small and medium-sized tourism enterprises. The entrepreneurial path to success includes qualities that entrepreneurs possess which enable them to use intuition and competitive intelligence, as they play a significant role towards success and the sustainability of a business (Amiri and Marimaei, 2012; Burns, 2014; Bhat and Singh, 2018). There are personality qualities that are often associated with entrepreneurship which include competitiveness, intelligence, determination, independence, confidence, intuition, imperiousness, and innovativeness, to mention a few (Louw and Venter, 2013; Bongomin, et al., 2018; Wathanakom, Khlaisang and Songkram, 2020). Therefore entrepreneurs should have self efficacy to perform better. Aspects of self efficacy include behaviour, motivation, human experience and cognition (Huang and Pearce, 2015). These qualities go hand-in-hand with the ICI that small and medium-sized tourism enterprises require to succeed in their businesses and be sustainable.

Small business owners in the tourism sector should have entrepreneurial intuitive minds to explore opportunities in the market environment and to use them to deliver results beyond the expectations of tourists and other stakeholders. At the same time, they should stay vigilant to potential threats that may affect their operations and hinder their path to success and sustainability (Mutyenyoka and Madzivandila, 2014; Danish, et al., 2019).

Literature Review – The Intuitive Completive Intelligence Model

Hodgkinson, Langan-Fox and Sadler-Smith (2008) believe that intution is the way we receive, store and process as well as retrieve information from our brains so as to be able to make decisions. This enables one to determine whether something is wrong or right. Like managers in big businesses, they sometimes use intuition to make decisions. This normally occurs when someone feels that he/she is under pressure, there is risk involved and there is a lack of information, and uncertainty prevails. They also believe that a person practises intuition in evaluating such internal and external cues and is not sure of which one is correct (Sadler-Smith, 2016; Aujirapongpan, et al., 2020). Intuition may further be viewed as act of sensing without use of rational processes but an immediate cognition. This includes a sense of something not perceptible or reasoned, or just a belief (Cholle, 2011). Du Toit (2015) believes that dynamic and complex competitive environment forces managers to be rational when making decisions. When executive authorities are faced with highly volatile environments, overwhelming information and need to make a rapid decision about a complex problem, they should use intuition instead of rational deliberation (Hayasi, 2001) as cited by Chaston (2009; Teece, 2018). According to UK Studies, intuitive thinking is a preferred business style and relates to superior small firm performance (Botha and Boon, 2008; Loureiro and Garcia-Marques, 2018; Kiel, 2019).

Laszczak (2012, cited in Kamila, 2018) believes that intuition plays some key roles in enhancing business operations, such as the filling of knowledge gaps and enabling the use of knowledge that is difficult to say by word of mouth, although outcomes come from experience. He further says that intuition assists in the application of decision-making procedures, as well as by giving a decision maker a sense of reality by offering him an opportunity to make a decision. Application of intuitive thinking takes place in various situations such as information gaps, lack of time and resources, information overload and increased levels of uncertainty (Kamila, 2018). Therefore, small tourism businesses can improve their performance by applying the intuitive thinking style when confronted with urgent decisions.

Van Rensburg and Ogujiuba (2020) view intuition from mind-power ability as the final performance enhancing factor towards the success of entrepreneurs and small businesses. Mind-power ability refers to underlying internal drivers that assist entrepreneurs to perform better. They include such aspects as mindfulness (intuition), visualisation of goals to be achieved, and a sense of self-belief (confidence) (Burch, Cangemi and Allen, 2017; Kier and McMullen, 2018). A study conducted by van Rensburg and Ogujiuba, (2020) on 15 participants who were farmers in the agricultural sector in the Western Cape, South Africa, revealed that mind-power ability assisted these farmers to perform well and succeed in their different fruit and vegetable businesses. Furthermore these entrepreneurs manipulated both their conscious and subconscious minds to change any type of thought and directed it towards the envisaged outcomes, whether positive or negative. They aver that the positive effects of mind-power ability are encouraged for entrepreneurs and small businesses in South Africa, to be learned, developed and applied on a continuous basis to overcome obstacles in a consistent manner.

Huang and Pearce (2015) and Rasca and Deaconu (2018) maintain that entrepreneurs should have qualities of self-efficacy to perform better. These qualities of self-efficacy include behaviour, motivation, human experience and cognition (intuition) which can assist them to solve problems in this competitive environment. This also applies to other disciplines such as sports, medicine, education, law and banking sectors (Comeig, et al., 2016).

On the other hand, competitive intelligence is generally associated with the formal organisational function tasked with gathering, analysing and applying information aimed at delivering a competitive advantage to a specific organisation. The review above demonstrates that this is generally applied in large organisations. It is widely known that small businesses have neither capacity nor wherewithal to organise the function. Yet, competitive advantage lies at the heart of a small business’s existence (Mina, Surugiu, Surugiu and Cristea, 2014). It is thus speculated that success (existing or aspirational) fulfils the function, if not formally, then intuitively.

ICI (ICI) is thus advanced as fulfilment or yield of competitive intelligence delivered intuitively by entrepreneurs. Therefore, ICI practices may include evaluation of business environment by a manager in his own way. That is, examining the manner in which consumers behave, determining one’s own current prices of products and services whilst comparing them with those of rivals as well as checking actions of the competitors with the aim of beating them (Stefanikova, Rypakva and Moraucikova, 2015). During this process, there are no formal structures designed, no methods and tools created to apply competitive intelligence and no procedures followed. These seem plausible in the context of SMEs and, in particular, SMTEs.

It is worth noting that SMTEs’ success and sustainability depends on the qualities of the entrepreneurs, as mentioned in Chapter One above. A brief overview concerning entrepreneurs will be done below. Small business enterprises, more especially in the tourism sector, are owned and managed by one person who should have entrepreneurial orientation to succeed in the business (Kiyabo and Isaga, 2020). This person is responsible for all functions and decisions made concerning the operations of the tourism business, hence he/she needs to possess the brequisite skills and experience. Meressa (2020) also concurs with the above authors that successful small businesses depend on the qualities, skills and experience of owner/manager.

Another research study on entrepreneurial orientation that could boost the success of hotels was conducted by Njoroge, et al. (2020) with 346 hotel managers in Tanzania. Results indicated that successful hotels employ managers that have entrepreneurial orientation in terms of innovativeness by providing good quality services that are standardised with product innovation that utilises advanced technology. As far as proactive risk taking is concerned, they make strong and risky decisions in identifying opportunities and are not necessarily influenced by the actions of their rivals. In addition, their approach to competition involves reliance on customer management, extensive marketing and flexible pricing based on competition. However these strategic actions are applicable only in western contexts and not necessarily in emerging economies like Tanzania, and the Eastern Cape Province for that matter. These hotels also need to be vigilant with environmental factors such as economic trends, culture and society that shape entrepreneurial opportunities. This research study indicates that companies that employ managers with entrepreneurial expertise tend to perform better than those that do not have such a calibre of managers.

A study that was conducted by Zhou, et al. (2019) in China with over 46 000 entrepreneurs revealed that personality differences, whether positive or negative, influence one’s performance. The study concluded that entrepreneurs that have a positive attitude and drive tend to succeed more than those that do not have them. This then leads to the identification and evaluation of theories of competitive intelligence, with the aim of adopting the one that will be used for the study.

Problem Statement

Literature indicates that small businesses just use whatever information they get to their competitive advantage, without following any specific procedures (Bhorat and Steenkamp, 2016; Bhorat, et al., 2018). Managers of big businesses in various disciplines, on the other hand, apply intuition to make informed decisions when confronted with complex situations that need urgent solutions (Sewdass and Du Toit, 2014; Du Toit and Sewdass, 2014).

Competitive intelligence has been used by big businesses and small businesses alike in developed countries, but not necessarily by small and medium-sized enterprises in the tourism sector in South Africa (Gaspareniene, Remeikiene and Galdelys, 2013; Fakir, 2017). These businesses scan the environment to get intelligence in order to outcompete their rivals. Information gathered through this process normally follows some steps as big businesses have well-structured units equipped with CI experts to do such work (Matlay, 2000; Uit Beijerse, 2000). On the other hand, high costs associated with the level of expertise and skills imply that SMEs are not well resourced to employ qualified experts who are vital for company growth (Agwa-Ejon and Mbohwa, 2015).

According to South African Tourism (2015) and Maleka and Fatoki (2016), small and medium-sized enterprises with their own challenges of sustainability influence tourism industry. One of the challenges is that they do not possess the competencies and skills to adopt the latest communication technologies which can assist them to get information from the market environment, and to use intuition to make informed decisions that can lead to entrepreneurial success and sustainability (Lituchy and Rail, 2000; Williams 2003:19; Sewdass and Du Toit, 2014). Literature indicates that they lack a formal and systematic way of managing knowledge, which is important for successful implementation of ICI practices (Pellissier and Nenzhelele, 2013). Given these numerous obstacles which influence SMTE success, ICI is of fundamental importance, (Deltl, 2013), although questions are still being raised on whether it is used by these SMTEs (and to what extent) (Fakir, 2017). In this case, its abandonment can possibly affect financial performance along with ultimate business closure of SMTEs.

In the South African context, literature that focuses on the successful implementation of ICI practices has been scanty (Bi and Cochram, 2014). Adoption of ICI practices by vulnerable SMTEs could possibly be an important source of firm competitiveness to manage the many problems they encounter and become successful as well as sustainable (Ghobakhloo and Tang, 2015; Bongomin, et al., 2018). In this vein, given that ICI adoption in SMTEs within the South African context may possibly remain unknown, this study sought to bridge that existing gap by investigating how ICI adoption in SMTEs can influence their entrepreneurial path to success and sustainability, and to employ the study’s results to propose an ICI Framework to comprehend and research it as an activity.

The Aim of the Study

The aim of the study is to assess whether small and medium-sized enterprises in the tourism sector of the Eastern Cape employ ICI to enhance competitiveness and sustainability in the business world. Given the research questions and the aim of the study defined above, the research objectives are to: determine what practices assist small and medium-sized enterprises in the Eastern Cape tourism sector to succeed in the business world; ascertain how small and medium-sized enterprise characteristics in the Eastern Cape tourism sector affect their ICI; investigate whether external forces influence the ICI practices of small and medium-sized enterprises in the Eastern Cape tourism sector; explore external forces contingent on the relationship between ICI practices and success for small and medium-sized enterprises in the Eastern Cape tourism sector; and to identify a framework that can be developed to enhance understanding and research on ICI practices for small and medium-sized enterprises’ success in the Eastern Cape tourism sector.

Research Question

Do small and medium-sized enterprises in the Eastern Cape tourism sector use ICI practices to succeed in business world?

Significance of the Study

Small and medium-sized tourism enterprises play a significant part in South Africa, as they provide job opportunities to local communities which in turn improve their standard of living and boosts economic growth. Therefore, sustainability of SMTEs is integral for development of the country. SMTEs are to be introduced to ICI practices to help them to identify their competitors, learn consumer trends and the behaviours of tourists, develop negotiation skills for dealing with suppliers and to be alert to environmental factors such as technology, the economy, society, politics and government demands that affect their small business enterprises. This can assist them to learn how to serve their customers (tourists) excellently, as well as how to deal with challenges to become successful and sustainable. The relevant government departments such as the Department of Tourism, the Department of Economic Development and Tourism, the Department of Trade and Industry and the Department of Small Business Development can use ICI for policy development to enhance and support SMTEs, by providing funding, training and mentoring, as well as assisting them to access markets. Furthermore, the study tries to encourage district and local municipalities to learn to assist SMTEs with their registration with the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC), the South African Revenue Service (SARS) and the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF), capacitation and training them in business management skills.

The ICI Framework may influence students to adopt it when doing business-management and tourism related courses both at schools and colleges, as well as at universities. Furthermore, the ICI Framework can influence further studies in tourism and the small business sector by developing an entrepreneurial mind in students to establish their own small businesses in future. The results of the study will be shared with SMEs in the tourism sector and relevant departments of government to try and assist them in enhancing tourism development.

The generation of knowledge through the study can be further utilised by researchers in both public and private sector organisations, through conference presentations and publications in accredited and peer-reviewed journals such as the African Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure, the Journal of Tourism Management, the Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Research, the Journal of Entrepreneurial Education and the Journal of Information Management. As a result, the researcher will develop both academically and professionally.

Research Methods

The study was conducted in the province of the Eastern Cape in South Africa, on the tourism sector using the quantitative research. According to Van Voorhis and Morgan (2007), quantitative research provides instructions and general rules on sample sizes which are essential for various statistical processes, unlike qualitative research which does not have an agreed sample size for its analysis procedure. This implies that each quantitative statistical process has general principles in relation to the sample size.

The target population was all the tourism business owners totalling 500 SMTEs (Eastern Cape Tourism Board, 2019). Out of 500 tourism business owners in the province, the questionnaires were distributed to a sample of 200 participants. Random sampling is when any individual is chosen randomly and has an equal chance of being included in the sample. Therefore, all the small tourism businesses had an equal chance to be chosen (Adler and Adler, 2011; Heale and Twycross, 2015). The sampling of tourists was done through the convenience sampling technique. In convenience sampling participants are selected based on their availability and willingness to participate (Bryman, 2012; Barrat and Shantikumar, 2018). Therefore, 99 tourists were conveniently sampled and involved in the study.

The general rule of thumb for the statistics employed to investigate association (correlation and regression) is 50 and above participants (Cohen, 1988; Van Voorhis, 2007; Delice, 2010). In this vein, other scholars proposed a formula based on the number of independent variables (Green, 1991; Delice, 2010; Collis and Hussey, 2014). In this case, Green (1991) expresses that if the study seeks to test the overall model, then the minimum sample size of 50 + 8k should be used where k is the number of independent variables. Then, if the study seeks to test individual independent variables then the minimum sample size of 104 + k should be deployed.

In this study, to effectively run multiple and logistic regressions and generate reliable results, the sample size collected from each group was thus at least 99 for tourists and 100 for business owners respectively. Participants from the public bodies numbered just 30, thus descriptive statistics were successfully generated. The total sample size for the study was therefore 229 participants (99 tourists; 100 business owners and 30 public body officials).

o

The results are presented in both decriptive and a more regorous statiscial computaions using regression analysis tools in order to get a deeper isnsight into SMTEs use of ICI. Specifically the discussion focussed on methods of employees’ use of ICI empowerment, whether the tourism business intuitively apply human resources management policies aligned with ICI , daily company income receipts when adopting ICI, how much money is spent by visitors per day on an average through y business ICI, the form of business advertising to tourists through ICI, whether the business owner is aware of competitors and the methods employed to monitor the actions of competitors as ICI approach.

The Methods to Emplower Employee ICI

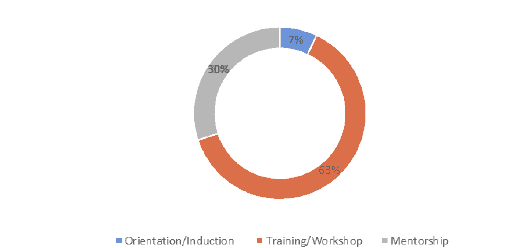

Figure 1 demonstrates the various approaches utilised by the respondents to empower their workers’ ICI. From the graph, 63 per cent of the participants made use of training and workshop methods to emancipate their employees. The second most popular form of employee empowerment was mentorship, which had a proportion of 30 per cent. Orientation and induction was the least preferred type of employee empowerment, as only seven per cent of the owners outlined that they used such an employee empowerment method.

Application of ICI

Table 1 extracted information to determine if small and medium tourism enterprises in the Eastern Cape area intuitively integrated human resource management policies. In this context, 86 per cent mentioned that they made use of such initiatives, and only 14 per cent did not indicate that they incorporated human resource management policies.

| Table 1 Showing Whether The Tourism Business Intuitively Applies Human Resources Management Policies |

||

|---|---|---|

| Application of HR policies | Yes | No |

| Number | 86 | 14 |

| Percentage (%) | 86 | 14 |

Daily Receipts Linked to the Adoption of ICI

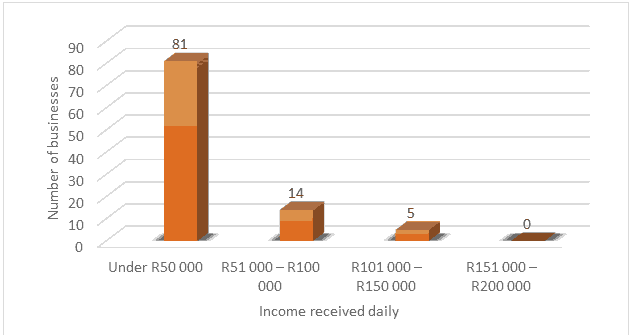

Figure 2 depicts information on the daily revenues of the tourism businesses in the Eastern Cape region who adopted ICI. From the presentation, 81 per cent illustrated that they obtained under R50 000 in income on a daily basis. Fourteen per cent of the respondents demonstrated that they acquired between R51 000 to R100 000 in revenue every day, with only five per cent of the owners acquiring between R101 000 and R150 000 in income on a daily basis. Of the business enterprises studied, none earned monies within the range of R151 000 to R200 000 on a daily basis.

Budget Spent of Tourists

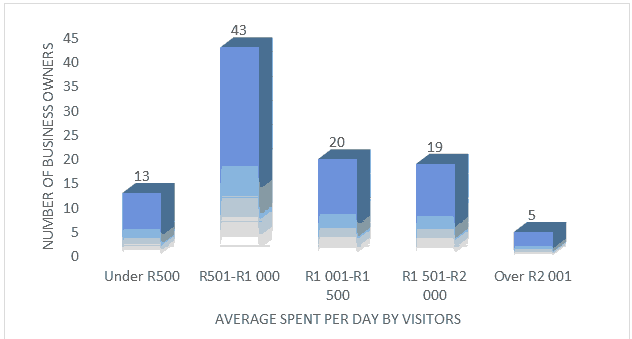

Figure 3 illustrates the monies that visiting tourists spent on a specific day on an average basis through business ICI, on the small and medium tourism enterprises studied in the Eastern Cape region. The largest number of business owners (43%) provided proof that the tourists used between R501 to R1 000 daily. Those tourists who spent between R1 001 to R1 500 and R1 501 to R2 000 were confirmed by representations of 20 per cent and 19 per cent, respectively. Furthermore, some respondents (13%) supported that under R500 was used by their visitors, while five per cent of the participants understood that their visitors used over R2 001 on a daily basis.

Figure 3: Showing How Much Money Is Spent By Visitors Per Day On An Average Basis Through Your Business

The Form of Business Adverstisng

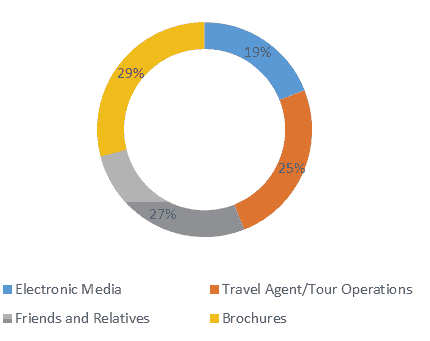

Figure 4 indicates the type of business advertising which their business owners deployed to market their goods and services through ICI. The information showed that most participants (29%) showed greater preferences for using brochures when advertising their commodities. Twenty-seven per cent favoured friends and relatives, whilst twenty-five per cent supported travel agents and tour operations services. Nineteen per cent of the business owners made use of electronic media to advertise their goods and services which was the lowest approach to business advertising popular with the participants.

Awareness of Competitors

Table 2 shows information on the level of awareness of the business owners regarding the competition in the industry. On one hand, 84 per cent of the participants confirmed that they were conscious of the presence of rivalries in this tourism industry. On the other hand, 16 per cent agreed that they were not aware of the competitors in this tourism industry.

| Table 2 Showing The Whether The Business Owner Is Aware Of Competitors |

||

|---|---|---|

| Aware of Competitors | Yes | No |

| Number | 84 | 16 |

| Percentage (%) | 84 | 16 |

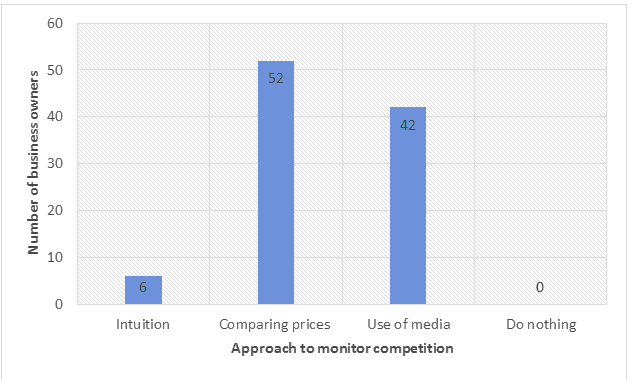

Figure 5 indicates the techniques incorporated by the participants to manage the actions of the competitors in the tourism industry. The information indicates that the most popular approaches were comparing prices (52%) and the employment of media platforms (42%). Moreover, intuition (6%) was also supported by the participants as a method of monitoring their rivals’ operations and strategies. None of the business owners highlighted that they did nothing to manage their competitors’ strategies and actions.

Multiple Regression

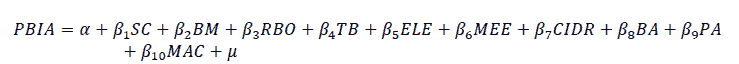

The main purpose of multiple regression is to understand more details regarding the association involving several independent or predictor variables and a dependent or predicted variable. In this study, the Multiple Regression Model was applied to find the factors that had an effect on business owner longevity in SMME tourism practices in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. The understanding of those factors that influenced business owner longevity was vital to establish the context in which the small and medium-sized tourism enterprises deployed ICI to thrive in the business market. Therefore, the dependent variable of the Multiple Regression Model was the period that the business had been intuitively active (PBIA). The independent variables were the source of capital (SC), form of business membership (BM), racial background of the owner (RBO), type of tourism business (TB), education level of employees (ELE), method of employee empowerment (MEE), company income daily receipts (CIDR), form of business advertising (BA), pricing approach (PA), and the methods used to monitor the actions of competitors (MAC).

The specific Multiple Regression Model was therefore:

Where

PBIA= Period Business Intuitively Active

SC= Source of Capital

BM= Business Membership

RBO= Racial Background of Owner

TB= Type of Business

ELE= Education Level of Employees

MEE= Method of Employee Empowerment

CIDR=Company Income Daily Reciepts

BA= Business Advertising

PA= Pricing Approach

MAC= Monitor Actions of Competitors

a=Intercept

ß1,ß2,ß3…=Coefficient Parameters

µ=Error Term

Table 3 provides an extensive evaluation of the fundamental features of the variables in the Multiple Regression Model. It demonstrates that the mean of all the variables lay within the range of 1.00 to 2.60. Moreover, 45.5 per cent of the variables were negatively skewed, while 54.5 per cent of the factors illustrated positive skewness. More elaborately, the period in which the business had been intuitively active, source of capital, method of employee empowerment, form of business advertising and the methods employed to monitor the actions of the competitors were negatively skewed. Conversely, the form of business membership, racial background of the owner, type of tourism business, level of education of the employees, daily company income receipts and the approaches used to determine the prices were positively skewed.

| Table 3 Showing The Statistical Summary Of The Multiple Regression Model Variables |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Skewness | Kurtosis |

| PBIA | 100 | 2.07 | 0.6396811 | -0.0597822 | 2.451964 |

| SC | 100 | 2.44 | 0.9777319 | -0.3197959 | 2.189841 |

| BM | 100 | 2.27 | 1.523254 | 0.2785174 | 1.264566 |

| RBO | 100 | 1.91 | 0.5876679 | 0.9155922 | 6.494796 |

| TB | 100 | 1.28 | 0.6278788 | 4.970427 | 32.79938 |

| ELE | 100 | 2.25 | 0.7703469 | 0.2081898 | 3.395654 |

| MEE | 100 | 2.22 | 0.5959459 | -0.3966918 | 3.950188 |

| CIDR | 100 | 1.22 | 0.5610236 | 1.745995 | 6.178681 |

| BA | 100 | 2.6 | 1.172065 | -0.3177768 | 2.00173 |

| PA | 100 | 1.53 | 1.218171 | 0.5196177 | 2.721428 |

| MAC | 100 | 2.36 | 0.5949281 | -0.3138013 | 2.31682 |

Table 4 above illustrates the one-to-one relationships between any two variables considered in the Multiple Regression Framework. The table highlights the period in which the business had been intuitively active, the source of capital, form of business membership, racial background of the owner, level of education of the employees, daily company income receipts, form of business advertising and the methods employed to monitor actions of competitors were positively associated. For example, a one per cent increase in the source of capital resulted in a 0.0633 rise in the possible period of the business staying intuitively active. To the contrary, the type of tourism business, method of employee empowerment and the approach used to determine prices demonstrated a negative relationship with the period the business stayed intuitively active. For instance, a one per cent increase in an approach used to determine prices resulted in a 0.0222 probability decrease in the possible period that the business would stay intuitively active.

| Table 4 Showing Correlation Coefficients Among Multiple Regression Model Variables |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBIA | SC | BM | RBO | TB | ELE | MEE | CIDR | BA | PA | MAC | |

| PBIA | 1 | ||||||||||

| SC | 0.0633 | 1 | |||||||||

| BM | 0.0426 | -0.006 | 1 | ||||||||

| RBO | 0.205 | 0.0169 | -0.108 | 1 | |||||||

| TB | -0.179 | 0.1392 | 0.1878 | -0.141 | 1 | ||||||

| ELE | 0.0051 | 0.0268 | 0.1227 | 0.0502 | 0.1986 | 1 | |||||

| MEE | -0.2 | -0.099 | 0.0786 | -0.203 | 0.0821 | 0.077 | 1 | ||||

| CIDR | 0.1255 | 0.0243 | 0.0125 | 0.1832 | 0.0645 | -0.082 | -0.297 | 1 | |||

| BA | 0.0108 | -0.197 | -0.126 | 0.0352 | 0.0131 | -0.078 | 0.0116 | 0.151 | 1 | ||

| PA | -0.022 | -0.071 | -0.111 | 0.0109 | -0.051 | -0.261 | 0.1021 | 0.005 | 0.235 | 1 | |

| MAC | 0.7294 | 0.1591 | -0.019 | 0.2092 | 0.0411 | -1E-04 | -0.197 | 0.154 | 0.064 | -0.085 | 1 |

Table 5 showed the variables regarding the impact of two or more variables on their relationship with the response variable (PBIA) through the integration of the Multiple Regression Model. On one hand, the findings indicated that the form of business membership, racial background of the owner, level of education of the employees, daily company income receipts, approach used to determine the prices and the methods employed to monitor the actions of the competitors were positively associated with the length for which the business had been running. For example, a one per cent rise in the company income receipts daily led to a corresponding increase in the period for which the business had been intuitively active by 0.0223481. On the other hand, the source of capital, type of tourism business, method of employee empowerment and the form of business advertising demonstrated negative associations with the period over which the business had been intuitively active. For instance, a one per cent rise in the type of tourism business results caused a 0.1822397 probability decrease in PBIA. These findings will contribute and are imperative towards finding out if SMTEs apply ICI practices for purposes of growing their businesses and becoming competitive in the tourism sector.

| Table 5 Showing The Multiple Regression Model Results |

||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coef. | Std. Error |

| SC | -0.021355* | 0.0464238 |

| BM | 0.0416833* | 0.0294896 |

| RBO | 0.0157608** | 0.0784847 |

| TB | -0.1822397*** | 0.0582338 |

| ELE | 0.0477925** | 0.0601579 |

| MEE | -0.0522952* | 0.0790293 |

| CIDR | 0.0223481* | 0.0834643 |

| BA | -0.0226377** | 0.0396114 |

| PA | 0.0352531* | 0.0382369 |

| MAC | 0.7939964*** | 0.0769343 |

| R-squared | 0.5946 | |

| Root MSE | 0.42956 | |

Conclusions and Recommendations

Seemingly, small enterprises do apply certain aspects of ICI, but they do not necessarily articulate them in documents such as competitor analysis. The businesses may not be aware that they are using them since they do not have well established structures. They tend to use portions of different competitive intelligence models, which each have their own strengths and weaknesses. This has been supported by the literature review as well as the empirical study results

The study sought to determine if the tourists had an influence on SMTEs in the application of ICI practices to improve their business operations for entrepreneurial success and sustainability. When tourists commented, for instance using suggestion boxes, they gave business owners impressions of their competencies and areas for improvement. In addition, the study aimed at determining if they provide all kinds of support to these small tourism businesses, as mentioned and mandated in the respective tourism-related government departments such as DEDEA, the National Department of Tourism, the Department of Small Business Development, and the Department of Trade and Industry. Hence the ICI Framework was recommended for use by small and medium-sized tourism enterprises in the Eastern Cape Province.

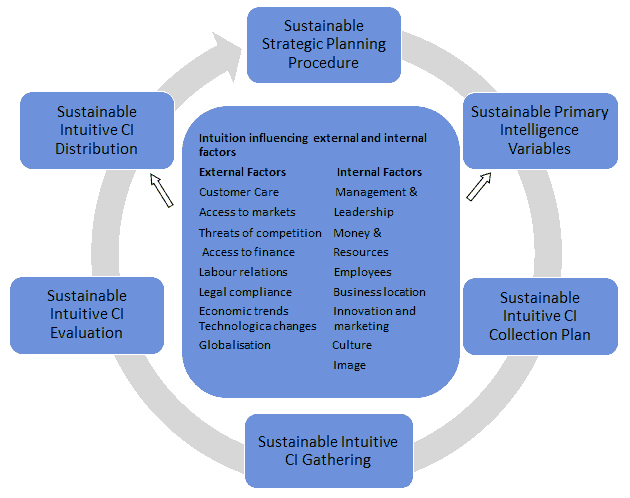

In congruence with past studies, the study identified both intuition, external and internal factors which influence intuitive competitive intelligence practices for SMETs success in the tourism sector. Hence, the study contributes to literature by integrating these factors in operation of small and medium-sized tourism enterprises which advantageously improve their financial and overall performance in South Africa. Apart from this research gap, no past studies have proposed a framework on ICI practices for small and medium-sized enterprises’ success in the tourism industry. In this regard, the framework is graphically presented in Figure 6 below.

Components of the Research Framework

The ICI Cycle used in the study was founded upon previous theories, empirical literature and study’s findings to help business enterprises and organisations to continue assessing a competitive environment in an orderly manner. The ICI Framework proposed in this study comprises of the following steps:

Step 1: Sustainable Strategic Planning Procedure

This is the starting point for the process of intuitive competitive intelligence. It gives direction that involves scope of the entire organisation. SMTEs start by identifying needs for gathering relevant data about the factors that affect their businesses both internally and externally. All the phases of the competitive intelligence process are interconnected and therefore the success of one relies upon the other. An effective intelligence process concentrates on gathering relevant competitive data that is key for tourism business managers to intuitively make informed decisions. This phase gives direction that is significant to the effort of competitive intelligence, making sure that it focuses on gathering and evaluating data relevant to the specific needs of intelligence (Cook and Cook, 2000; Louw and Venter, 2011; Louw and Venter, 2013).

Step 2: Sustainable Primary Intelligence Variables

In this step, tourism businesses must identify critical areas for competitive intelligence, as it is not practical to assess the entire business environment. These critical areas are known as the sustainable primary intelligence variables. They should identify specific intelligence requirements for the entrepreneurial success of the business enterprise. For the process to succeed, they should be assigned to the specific units or departments, such as top management, in which strategic plans are taking place. Or they may be placed under the control of the marketing department where they will be able to intuitively identify changes that need the attention of managers in the business environment, including the threats of competitors, opportunities in the market place, and competitive risks. They must also check key vulnerabilities and assumptions that are real, technological trends, customer preferences and needs, and the actions of the government that adversely affect business operations if unchecked (Louw and Venter, 2013; Du Toit, 2015; Fakir, 2017).

Step 3: Sustainable Intuition CI Collection Plan

The sustainable intuition competitive intelligence collection plan should be created at this stage. This involves determining the data sources that will be used, the people involved in the collection process and how the data will be collected. Primary and secondary sources of data are used and further support each other when gathering data (Nikolaos and Evangelia, 2012; Nenzhelele, 2016; 2017). SMTEs’ examples of primary sources of data include data received from the opinions of customers, workers, competitors, suppliers, employees, distribution channels, opinion leaders and complementors (forms part of competitive intelligence). On the other hand, secondary sources of data consist of information sourced from institutions that specialise in market research, the records of the company, public libraries and online sources such as the Internet. Some merits of using primary data are that it is correct and timely, although it is expensive, whereas secondary data is easily accessible and cheap, but may not be reliable since it is outdated. However, both types of data are useful in determining a sustainable competitive intelligence plan. One of the superb ways to collect competitive intelligence data is the use of the Internet.

Step 4: Sustainable Intuition CI Gathering

Sustainable intuition competitive intelligence data gathering is undertaken in this step as mentioned in the plan for data collection. It is the responsibility of tourism small businesses to check the value and credibility of the source of data. During this phase of the process, SMTEs intuitively get information from various primary and secondary sources as noted above, using a large number of available techniques. Primary sources include employees of both the business enterprise as well as that of the competitors, government agencies, customers, conferences, suppliers and tourism events in which tourism stakeholders are gathered. On the other hand, secondary sources consist of TV, radio, magazines, reports received from analysts, tourism annual reports as well as annual financial records of the organisation (Nenzhelele, 2017; Bi and Cochram, 2014). From empirical research in the respective it was clear that electronic media was the main source of information for small businesses in the tourism industry for gathering intuitive competitive intelligence.

The type of information required influences the choice of a particular source which incorporates such factors as availability, cost, quantity and quality of information, easy access together with ease of sorting the relevant source. There is a belief that 80 per cent of the information needed to produce competitive intelligence is discovered within a firm, however, users of the information are not aware of its existence since it is not necessarily shared with them. The challenge of not sharing information happens as a result of barriers to communication as well as the geographical location of the tourism business. This is due to the fact that most units in any big organisation tend to work in silos whereas in small businesses, the owner or manager may be ignorant (Louw and Venter, 2013; All Answers Ltd., 2018; Kompyte, 2018). Therefore, SMTEs should intuitively source information from employees and company records to get a better insight on how to improve their business operations.

Step 5: Sustainable Intuition CI Evaluation

This step is the most difficult one and involves the evaluation of competitive intelligence that has been gathered to check factuality and utility. This is so since some small tourism businesses do not have sufficient financial and human resources to assist with ICI evaluation of collected data. There are tools available designed to evaluate competitive intelligence. This phase also allows the CI professionals to identify gaps in data and findings. It is important to verify information before it is distributed to decision making managers for use. This demands that the owner or manager gets an insight of what the programme of competitive intelligence covers to eliminate information overload. However, the value of information is determined by time, accuracy, relevance and reliability.

It is worth noting that competitive intelligence or “actionable intelligence” saves managers time and effort since they get sifted information that enables them to make informed strategic and tactical decisions within a reasonable time period. To ease the burden of the difficulty, a variety of analytical tools are used to analyse information, including PEST (political/legal, economic, social-cultural and technological analysis), Porter’s Five Forces Model, SWOT (Strength, Weakness, Opportunity and Threats) analysis and competitor profiling. These analytical models are useful in converting various pieces of information into actionable intelligence which enhances the decision making process of small tourism businesses. Literature indicated that successful businesses are the ones that use these types of competitive intelligence models (Porter, 1980; Porter, 1990; Louw and Venter, 2013; Pellissier and Nenzhelele, 2013a).

The evaluation phase is completed by making a variety of intelligence products which are normally documents and activities such as market or industry analyses, company profiles, and supplier or customer profiles. Again they include competitive benchmarking that can assist SMTEs to copy and try to overcome their rivals, analysis of effects of the strategy, technology assessments, daily reports, bulletin of risk and opportunities and daily competitive intelligence. The analysis technique to be chosen depends on the type of intelligence required, such as tactical or strategic intelligence (Ettorchi-Tardy, Levif and Michel, 2012; Pellissier and Nenzhelele, 2013; Rogerson, 2014). The capability to undertake assessment that is fair and just, together with interpretation, is significant for the achievement of a sustainable competitive intelligence process of a small tourism business.

Step 6: Sustainable Intuitive CI Distribution

This phase is used to distribute information to strategic decision-makers with a view to planning and action which will then influence primary intelligence variables. Actionable intelligence allows various teams of executive management to make strategic decisions and actions aimed at boosting the overall performance and competitiveness as well as innovation of tourism business organisation. Competitive intelligence forms part of the value chain which converts some elements of data into usable information that results in strategic decision-making. The ultimate aim of competitive intelligence is to formulate rational decisions that can be actionable to assist tourism businesses to remain sustainable and competitive. This information is then communicated in an appropriate way to relevant parties (Erasmus and Strydom, 2013; Marketing, ABC, 2018).

The results of the intelligence process should be distributed to people with authority and responsibility to act on the findings in which reports, meetings or dashboards are normally used. This phase also includes the judgement of the competitive intelligence process and the examination of its impact in the process of making decisions. Another key aspect to consider is the feedback from decision-makers that can assist in future planning and improvement of the CI process of tourism businesses. Competitive intelligence requires that there should be relevant policies and procedures to support it. As discussed by the literature, workers should be capacitated about ICI practices in order to create awareness and the culture of competitiveness within the tourism business.

References

- Acheampong, K. (2015). South Africa’s eastern cape province tourism space economy: A system of palimpsest. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, Special Edition, 4, 1-18.

- Acheampong, K. (2015). Tourism policies and the space economy of the eastern cape province of South Africa: A critical realist perspective. African Journal of Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 21(3:1), 744-754.

- Acheampong, K. (2017). Tourism Policy. Tourism and Hospitality, 1(1), 256-280.

- Acheampong, K., & Tichaawa, T. (2015). Sustainable tourism challenges in the Eastern Cape Province: South Africa: The Informal Sector Operators' Perspectives. African Journal of Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 1, 111-124.

- Adom, A., Nyarko, I., & Som, G. (2016). Competitor analysis in strategic management: Is it a worthwhile managerial practice in contemporary times?. Journal of Resources Development and Management, 24, 116-126.

- African National Congress, (2004). Approaches to poverty eradication and economic development to transform the second economy. ANC, Today, 4.

- Afrika, J.G., & Ajumbo, G. (2012). Informal cross border trade in Africa: implications and policy recommendations, Tunis: African Development Bank Economic Brief.

- Aguinis, H., & Solarino, A. (2019). Transparency and replicability in quantitative research: The case of intervieww with elite informants. Strategic Management, 40, 1291-1315.

- All Answers Ltd. (2018). Competitive analysis of coca-cola: PEST and porter's five , s.l.: All Answers Ltd..

- Amiri, N., & Marimaei, M. (2012). Concept of entrepreneurship ans entrepreneurs traits and characteristics. Scholarly Journal of Business Administration, 2(7), 150-155.

- Armstrong, H., & Taylor, J. (2000). Regional Economics and Policy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Aujirapongpan, S., Jintanee ru-zhe, J., & Jutidharabongse, J. (2020). Strategic intuition capability toward performance of entrepreneurs; evidence from Thailand. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(6), 465-473.

- Bhosale, S., & Patil, R. (2019). A research on process of interaction between Business Intelligence (BI) and SMEs. International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering, 8(2S11), 913-918.

- Bischoff, C. & Wood, G. (2013). Micro and small enterprises and employment creation: A case study of manufacturing micro and small enterprises in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 30(4-05), 564-579.

- Bongomin, G., Munene, J., Ntayi, J. & Malinga, C. (2018). Determinants of SMME growth in post-war communities in developing countries: Testing the interaction effect of government support. World Journal of Entrepreneurship Management and Sustainable Development, 14(1), 50-73.

- Bose, R. (2008). Competitive intelligence process and tools for intelligence analysis. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 108(4), 510-520.

- Bose, R. (2008). Exploring SWOT analysis-where are now?. Journal of Strategy and Management, 3(3), 215-251.

- Botha, A., Smulders, S., Combrink, H., & Meiring, J. (2020). Challenges, barriers and policy development for South African SMMEs- does size matter?. Development Southern Africa

- Bruwer, J. (2019). Do accountancy skills of management influence the attainment of key financial objectives in selected South African goods small, medium and micro enterprises?. Acta Universitatis Danubius CEconomica, 15(2), 288-297.

- Bruwer, J., & Coetzee, P. (2016). A literature review of the sustainability, the managerial conduct of management and the internal control systems evident in South African small, medium and micro enterprises. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 14(2), 201-211.

- Bruwer, J., Coetzee, P., & Meiring, J. (2018). Can internal control activities and managerial conduct influence business sustainability? A South African SMME perspective. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(5), 710-729.

- Bryman, P., & Bell, E. (2011). Business Research Methods. 3rd edistion New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bushe, B. (2019). Causes and impact of business failure among Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in South Africa. Africa Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 7(1), 210.

- Calof, J. (2017). Reflections on the canadian government in competitive intelligence - programs and impacts. Foresight, 19(1), 31-47.

- Cant, M., & Wild, J. (2013). Establishing the challenges affecting south african small and medium-sized enterprises. International Business and Economics Journal, 12(6), 707-716.

- Cass, A., & Sok, P. (2014). The role of intellectual resources, product innovation capabillity, reputational resources and marketing capability combinations in firm growth. International Small Business Journal , 32(8), 996-1018.

- Cavallo, A., Sanasi, S., Ghezzi, A., & Rangone, A. (2020). Competitive intelligence and strategy formulation: Connecting the dots. International Business Journal , 1-26.

- Ceptureanu, S. (2015). Competitiveness of SMES. Business Excellence and Management, 5(2), 55-67.

- Chidoko, C., Makuyana, G., Matungamire, P., & Bemani, J. (2011). Impact of the informal sector on the current zimbabwean economic environment. International Journal of Economics and Research, 2(6), 26-28.

- Chiliya, N., Masocha, R., & Zindiye, S. (2012). Challenges facing Zimbabwean cross border traders trading

- Coca-Cola Ltd., (2017). Coca-Cola Annual Report, s.l.: Coca-Cola Ltd..

- Coetzee, J., Hendricks, F., & Wood, G. (2001). Development Theory, Policy and Practice. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Collis, J., & Hussey, C. (2014). Business Research. Palgrave: Basingstoke.

- Constantiou, I., Shollo, A., & Vendelo, M. (2019). A study investigating cognitive styles on using intuition in decision making and entrepreneurship. Decision Support Systems, 121, 51-61.

- Cooper, C., Fletcher, J., Fyall, A., & Wanhill, S. (2008). Tourism: principles and practice. 4th edistion London: Prentice-Hall.

- Degaut, M. (2015). Spies and policymakers: Intelligence in the information age. Intelligence and National Security.

- Department of Labour, (2008). Tourism Sector Studies Research Project, Pretoria: Research Consortium.

- Department of Tourism, (2019). Department of Tourism Annual Report 2018/2019, Pretoria: Department of Tourism.

- du Toit, A. (2015). Competitive intelligence research: An investigation of trends in the literature. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business, 5(2), 14-21.

- du Toit, A. & Sewdass, N. (2014). Competitive intelligence in morocco. Afri. J. Lib. Arch. & Inf. Sc., 24(1), 3-13.

- Eastern cape development corporation, (2007). The Eastern Cape Economy.

- Eastern cape government, (2004). Socio-Economic Profile: Provincial Growth and Develoment Plan 2004-2014, Bhisho: ECDC Building.

- Eastern cape socio-economic consultative council, (2011). The Eastern Cape Economy: Quarterly Economic Update Third Quarter, December, Vincent, East London: ECSECC.

- Eastern cape socio-economic consultative council, (2018). Growth and Employment: Quarterly Economic Update Fourth Quarter, East London: ECSECC.

- Eastern cape socio-economic consultative council, (2018). Quarterly economic update, East London: ECSECC.

- Erasmus, B., & Strydom, J. (2013). Introduction to Business Management. 9th ed. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Fakir, K. (2017). The Use of Competitive Intelligence in the sustainability of SMMEs in the Buffalo City Metropolitan Municipality. Masters in Business Administration. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Municipality: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University.

- Fatoki, O. (2014). The causes of the failure of new small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Meditarranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 922-927.

- Fatti, A., & Du Toit, A. (2013). Competitive intelligence in pharmaceutical industry. Journal of Intelligence Studies in Business , 1(1), 5-14.

- Gaspareniene, L., Remeikiene, R., & Galdelys, V. (2013). The opportunities of the use of competitive intelligence in business: Literature review. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Development, 1(2), 9-16.

- Harrison, J.F.R., & Sa de Abreu, M. (2015). Stakeholder theory as an ethical approach to effective management: Applying the theory to multiple contexts. Review of Business Management, 17(55), 858-869.

- Louw, L., & Venter, P. (2011). Strategic Management: Developing Sustainability in Southern Africa. 2nd edistion Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Louw, L., & Venter, P. (2013). Strategic Management: Developing Sustainability in Southern Africa. 3rd edistion Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

- Malgas, M., & Zondi, W. (2020). Challenges facing small business retailers in selected South African townships. Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 12(1 a 202).

- Muller, M., 2009. How and what others are doing in competitive intelligence: Various CI Models. Competitive Intelligence, 11(1), pp. 1-8.

- Mutyenyoka, E., & Madzivandila, T. (2014). Employment creation through Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises (SMMEs) in South Africa: Challenges, progress and sustainability. Mediterranean Journal of Sciences, 5(25).

- Nenzhelele, T. (2016). Competitive intelligence practice: Challenges in the South African property sector. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 14(2-2), 298-305.

- Nenzhelele, T. (2017). Adoption of Competitive Intelligence Ethics in the ICT Industry of South Africa. Pretoria: University of South Africa.

- Niewenhuizen, C. (2019). The effect of regulations and legislation on small, micro and medium enterprises in South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 36(5), 666-677.

- Njoroge, M., Anderson, W., Mossberg, L., & Mbura, O. (2020). Entrepreneurial orientation in the hospitality industry: Evidence from Tanzania. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(4), 523-543.

- Pellissier, R., & Nenzhelele, T. (2013 a). The impact of work experience of small and medium-sized enterprises owners or managers on their competitive intelligence awareness and practices. South African Journal of Information Management, 15(1), 1-6.

- Pellissier, R., & Nenzhelele, T. (2013). Towards a universal competitive intelligence process model. South African Journal of Information Management, 15(2), 567-574.

- Porter, M. (1980). Competitive Strategy: Techniques of analyzing industries and competitors. New York: The Free Press.

- Porter, M. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations. New York: MacMillan.

- Republic of South Africa, (2004). National Small Business Amendment Act, Pretoria: Republic of South Africa.

- Reynolds, A., Fourie, H., & Erasmus, L. (2019). A generic balanced scorecard for small and medium manufacturing enterprises in South Africa. The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, 11(1), 2522-7343.

- Ritcher, U., & Dow, K. (2017). Stakeholder theory: A deliberative perspective. Business Ethics, 26(4), 428-442.

- Rogerson, C. (2015). Progressive rhetoric, ambiguous policy pathways: Street trading in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. Local Economy.

- Statistics South Africa, (2018). How important is tourism to the South African Economy?, Pretoria: Statistics South africa.

- Statistics South Africa, (2019). Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Pretoria: Statistics South Africa.

- Tsogo Sun, (2019). Integrated Annual Report. 50 Years of Hospitality and Entertainment, Johannesburg: Tsogo Sun.

- United Nations & United Nations World Tourism Organisation, (2008). International Recommendations for Tourism Statistics. Madrid/New York: UNWTO.

- Viviers, W.A.S., & Muller, M. (2005). Enhancing a competitive intelligence culture in South Africa. International Journal of Social Economics, 32(7), 576-586.

- Weiss, A., & Naylor, E. (2010). Competitive intelligence: How independent information professionals. American Society for Information Science and Technology, 37(1), 30-34.

- Zulkelfli, N. (2015). A business intelligence framework for higher education institutions. ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, 10(23), 1-10.