Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 2

The Impact of Forestry Policies on Ethnic Minorities In the Central Highlands of Vietnam

Tran Quoc Hung, Thai Nguyen University of Agriculture and Forestry

Dang Kim Vui, Thai Nguyen University of Agriculture and Forestry

Do Hoang Chung, Thai Nguyen University of Agriculture and Forestry

Bao Huy, Tay Nguyen University

Abstract

In order to assess the impacts of forestry policies on ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands of Vietnam in the protection and development of forest resources from the renovation stage to the present (the year 1986 up to now), the research topic has been studied from reports and applied forestry policy documents as well as analysis scientific articles. The research also carried out surveys in 2 provinces of Gia Lai and Dak Lak with representative’s households. The research results have showed that the government's forest protection and development policies have impacted on the lives of ethnic minority communities in the Central Highlands of Vietnam in both positive and negative aspects. So far, the status of forests allocated to ethnic minority households and communities in the Central Highlands has been affected to varying degrees. The forest management of households and communities faces many challenges; Benefit from the forest protection and management has not yet contributed to household livelihood income, so it has not attracted people interested in forestry and forest management and protection. The rate of forest allocation to households and communities in the Central Highlands region of Vietnam is generally very low, only about 3.9% of the forest area and forestry land. Therefore, it is necessary to have specific solutions and policies to develop livelihoods for ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands in association with sustainable forest management.

Keywords

Forestry Policy, Livelihood, Ethnic Minority, Central Highands

Introduction

The Central Highlands is one of the areas with very high biodiversity in Vietnam with a total natural area of 54,474 km2 (accounting for 16.8% of the country's area). The Central Highlands forest is rich in reserves and diverse species. Timber forest reserves account for 45% of the total timber reserve of the country. The forest and forest land area of Central Highlands are 3,015,500 ha, accounting for 35.7% of the country's forest area. The Central Highlands forest has an important position and role in socio-economic development and traditional cultural values, defense security and environmental protection. Forests are considered the source of spiritual life, the deepest part of people and communities of the Central Highlands. Losing forests means losing the foundation and cultural identity of the Central Highlands. From 2010 to 2015, the Central Highlands is the region with the fastest and most serious forest degradation rate in the country, in terms of area, quality, total forested area decreased by 312,416 ha, forest coverage decreased by 5,8%, forest reserve decreased by more than 25.5 million m3, corresponding to a decrease of 7.8% of the total reserve.

Forests in the Central Highlands are associated with ethnic minority communities. The ethnic minority community in the Central Highlands has a rich cultural and livelihood life relating with the forest, from the traditional use of forest resources such as shifting cultivation, hunting and gathering in the traditional border areas of the village to the related policies of forest management and protection activities, forest land use changes and market mechanisms (Bao Huy, 2005, 2009a). However, at present, the conversion of forests to other purposes, the situation of free migration, illegal encroachment of forest land, violations of the law on forest protection are serious and complicated. In addition, due to the impact of climate change, extreme weather events, the droughts have had negative impacts and impacts on people's lives and socio-economic development and environment.

With the development and pressure of the society such as population growth, commodity and economic development, the state's forest management strategy also changes over time and affects many aspects of social, livelihoods of indigenous communities and their ability to protect and develop forests in the context of forest ecosystem degradation and climate change (Sikor et al., 2013).

The research is part of the national project on "Evaluating the effectiveness and impact of forest protection and development policies on ethnic minorities", the project is implemented under the program of the Committee for Ethnic Affairs, chaired by Thai Nguyen University.

Research Objectives and Method

Objective

In order to generalize the history of change in forestry policies related to the life of ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands period 1986 - today. Based on that, assessments of the impact of forestry policy on the lives of ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands will be made.

Research Methods

To achieve the objective, the research used methods such as: secondary data, analyzing documents, reports as well as previous studies on policies related to forest protection and management in the Central Highlands from 1986 - today. The analysis is conducted by policy group:

1. Land and forest allocation policies

2. Contract for forest protection

3. Policies for implementing the 5 million ha reforestation program.

4. Community forestry development policy

5. Forest benefit sharing policy (Forest environmental services)

In addition, the research also uses an additional survey method for ethnic minority households involved in forest protection and development. The survey implemented at 2 provinces of Gia Lai and Dak Lak, each province has 4 representative districts, each district has 2 representative communes, each commune has 50 ethnic minority households (2 provinces x 4 districts/province x 2 communes/districts x 50 households/commune=800 households).

Results and Discussion

History of the Change in Forestry Policies Related To Ethnic Minorities' Life in the Central Highlands

Before 1986

Traditional forest use: During this period, the community used forest land according to traditional shifting cultivation and village boundaries. Forestry policies were few and only slightly influenced on the lives of ethnic minority communities in the Central Highlands.

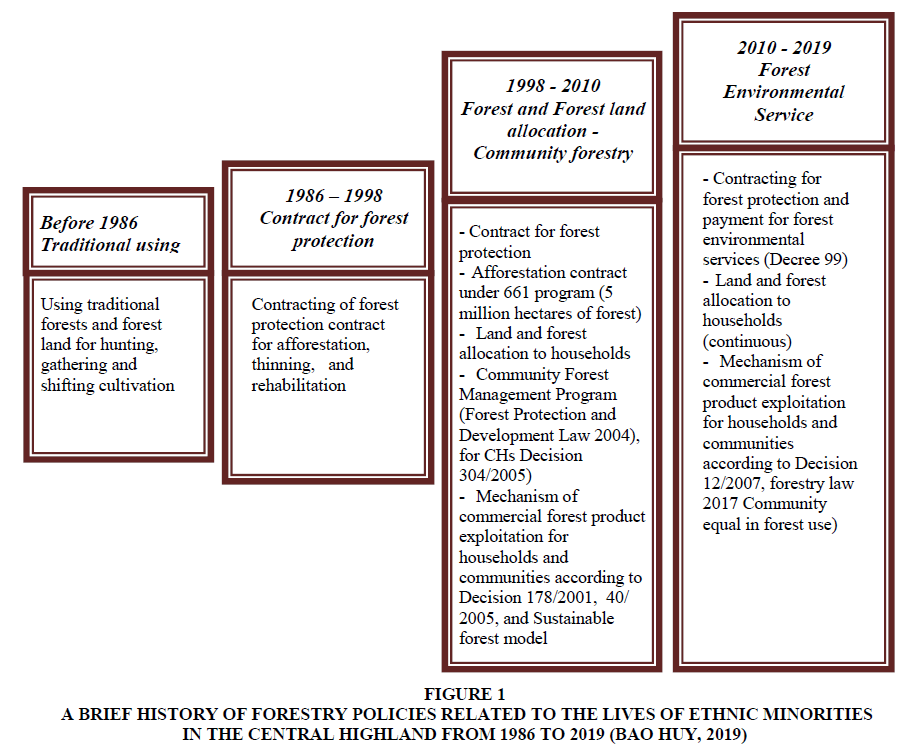

In the period of 1975 to 1986, most of the forests and forestry land were planned as timber production and managed under the system of State-owner Forest Enterprises (SFEs). With a large area of natural forest land in the Central Highlands, low density of people, the indigenous people can still continue to use forest land for shifting cultivation and gathering forest products even though it has not been recognized of forest land use rights Figure 1.

Figure 1 A Brief History of Forestry Policies Related to the Lives of Ethnic Minorities in the Central Highland From 1986 to 2019 (BAO HUY, 2019)

Period 1986 - 1998

Forest protection contract: The forestry policy affecting the local people in Central Highlands mainly during this period was forest protection policy.

With the population pressure, starting to mechanically increase from the new economic policy and free migration from the north to the Central Highlands, has led to the beginning of large-scale deforestation to obtain cultivated land and illegal timber exploitation. SFEs have encountered difficulties in forest protection. Therefore, in order to attract the participation of local people in forest protection, a policy on forest protection has been established. Forests and forest lands are under the management and use of SFEs, which are contracted to households for protection. The contract for forest protection has since been maintained until now.

During this period, SFEs were also responsible for attracting and solving local labor, so indigenous people were hired to participate in silvicultural activities such as afforestation, thinning, and cleaning forest after exploitation.

Period 1998-2010

Forest and forest land allocation, community forestry: Forest and forest land allocation, based on that creating the benefit from forests and community forestry development are the key policy in this period (National Assembly, Law on Forest Protection and Development 2004; Bao Huy, (2009), (2009b); Wode & Bao Huy, (2009); Prime Minister Decree 163/1999; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development TT38/2007). Forest land allocation in the Central Highlands started mainly from 1998; meanwhile forest land allocation to households, individuals, organizations, and communities has been carried out in many provinces since 1990s (Nguyen Thi Thu Phuong & Bob Baulch (2007), so the forest land allocation here is later than with other places in the country.During this period, the policy of contracting on forest protection continued, households continued participating in receiving forest protection contracts with SFEs and management boards of protection and special-use forests.

At the same time, the 5 million ha reforestation program (Prime Minister Decree 661/1998) associated with forest land allocation (Prime Minister Decree 163/1999) has also attracted indigenous communities to afforestation activities on the basis of forest land allocation. However, people are mainly involved in forestation contracts with SFEs. Forest land allocated to households for reforestation under this program in the Central Highlands is limited. This is against the objective of the SFEs shown in the study by Nguyen Thi Thu Phuong & Bob Baulch (2007) là “The other objective of SFE reform is to reallocate land to the ethnic minority households and communities for a more socialized forest management” Nguyen Thi Thu Phuong & Bob Baulch (2007).

The most outstanding is still the allocation policy of forest and forest land to households, then based on the characteristics of natural resources management of ethnic minority community in the Central Highlands, it has developed into the allocation of forest and forest land to households groups and communities (National Assembly Law on Forest Protection and Development (2004); (Prime Minister Decision 304/2005); Bao Huy, 2005, (2009a), (2000b); MARD TT38 / 2007; Wode & Huy, 2009).

Based on forest allocation to communities, many community forest management projects have been piloted in many localities throughout the country, of which concentrated in the Central Highlands have been implemented by international organizations such as German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ), Switzerland (SDC/Helvetas), Japan (JICA) in Kon Tum, Gia Lai, Dak Lak and Dak Nong provinces. Inheriting international projects, Vietnam Administration of Forestry - VNFOREST has used international partners' funds to implement a community forestry project in 10 provinces and 40 communes throughout the country, including many provinces in Central Highland (Bao Huy, 2007, 2008, 2009a, 2009b; Wode & Huy 2009).

Following the forest allocation policy, the beneficial policy for forest recipients has also been established, tested and developed such as Decree 178 of Prime Minister in 2001, Decision No. 40 (MARD, QD40/2005) on the regulation of logging and other forest products. At the same time, community forestry projects have developed the concept of "Sustainable Forest Model" as simple tools for the community to be able to actively exploit sustainable timber in the allocated forest plots. (Bao Huy, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009a, 2009b; Wode & Huy (2009); Bao Huy et al., 2012).

Period of 2010-2019

Forest environment services: Payments for environmental services include forest environmental service in watershed area under Decree 99 (Prme Minister ND99/2010; Pham et al., 2013) and carbon sequestration of the program “Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation - REDD +” has been the main policy from 2010 to the present (Bao Huy, 2012; Huy, 2015).

Payments for watershed services for community are often linked to forest protection contracts between SFEs and households and communities. Meanwhile, payment for carbon sequestration services is currently at a pilot level, with payments based on work outputs related to forest protection and investigation.

During this period, the beneficial policy forest for forest recipients has also changed according to Circular No. 12 (MARD, 2017) regulating the main harvesting and utilization of forest products (the Law on Forestry, 2017) communities have equal rights to exploit forest products as organizations and individuals with forest use rights.

Impact of Forestry Policies on Ethnic Minorities in the Central Highlands

Positive Impacts

Forest Land Allocation Policy: Studies have shown that this policy is a powerful decentralization and sharing of benefits of forest resources from the state to local communities. In some areas of the Central Highlands, there are positive impacts, such as: Some benefits from wood timber and non-timber forest products to the community from allocated forests are recorded; some pilot sites for commercial logging and benefit sharing in the community have been also recorded (Bon Bu Nor, Dak Nong; Tul village, Dak Lak; Taly village, Dak Lak) (Bao Huy, 2006, 2007, 2009a, 2009b; Bao Huy et al., 2012; Huy , 2007, 2008) (Cao Ly, 2014, 2018).

Many areas of shifting cultivation are recognized as being used by indigenous ethnic minority households. This ensures that they legalize traditional cultivated land and stabilize area under cultivation. This is a positive point and a good impact on land use management in the Central Highlands, suitable for traditional land management of indigenous people. From here a number of planted forest areas are developed on allocated forest land.

Policies on Forest Protection

This policy has begun to recognize the role of local people in forest protection and attracts a large number of indigenous people to the protection of natural forests. Most State-onwed forest enterprise (SFEs) in the Central Highlands carry out forest protection contracts with local people.

The benefit of this policy brings a part of cash income for the community. The average household contracted to protect about 5-10 hectares or more, with unit prices in the last 20 years ranging from 50,000 to 150,000 VND/ha. This income in the first phase was also quite significant for the poor, cash-poor households, however then gradually decreases because of spiralling prices and the reduction of the funding of forest protection.

Many forest areas are effectively protected by communities; many villages are organized into teams, groups and communities to protect forests. Begin a large, organized, collaborative process of community participation in forest protection by household groups and village communities.

The 5 million ha reforestation program (661 Program)

This is a large-scale and long-term program, attracting a large participation of local labor in afforestation. In the Central Highlands 100% of SFEs employ local labor for planting, tending, protecting and preventing forest fires; the same in study of Nguyen & Bob (2007) have showed that “Program 661 aim to increase nationwide forest coverage to 43 percent of the total land cover, while providing jobs to the rural poor and ethnic minorities and increasing the supply of forest products”. As a result, seasonal sources of employment have been created quite high in the ethnic minority areas, thus creating additional sources of income from labor (Bao Huy, 2006, 2007).

Community Forestry

With the limitations of natural forest management and protection by individual and household, many pilots allocating forests to household groups and communities were conducted before 2004 (Bao Huy, 2005, 2006, 2007a). Subsequently, the year 2003 Land Law and the 2004 Forest Protection and Development Law allowed the allocation of forest land to groups of households, clans, and communities. This is the basis to promote community forest management. This policy is really consistent with the habits, traditional management and use of natural resources of ethnic minorities in Central Highlands. Community-managed forests are much better protected than allocated to households or to SFEs. Community forest management in Bon Bu Nor in Dak Nong Province or Tul village in Dak Lak Province are examples (Bao Huy, 2006, 2007, 2009).

Benefits from Allocated Forests and Payment for Forest Environmental Services

In general, this policy has partly created conditions for ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands to benefit from two main forest products, namely timber and non-timber forest products Bao Huy (2006); Cao Ly (2014).

Up to now, the policy of payment for forest environmental services, specifically protecting watersheds of hydropower, has created a quite good motivation for forest protection in the country in general and in the Central Highlands in particular. This policy attracts the participation of a large number of households and indigenous communities because of the attraction of cash income. On average, each household received protection or allocated an average of about 10 ha of forest with the payment price of 200,000 to 600,000 VND / ha / year, thus generating cash income for each household from 2 to 6 million VND / year. This is not a high income for the household, but it is also a significant source of cash for poor households (Bao Huy, 2019). The implementation of this policy has also helped to improve the capacity, form teams, groups and communities to protect forests. Capacity of community organization, management and benefit sharing from forests was improved.

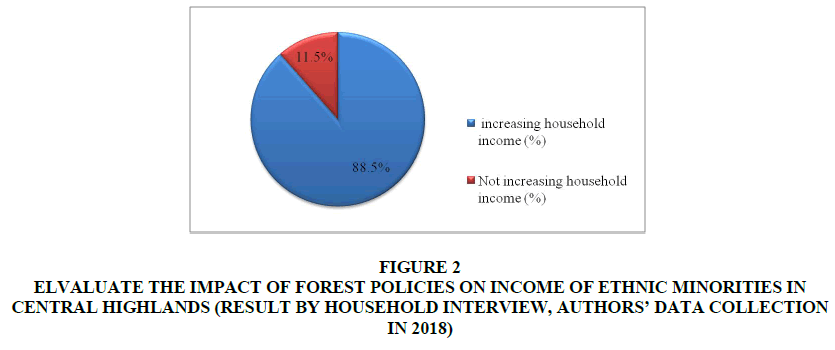

Assessing the actual positive impact of forestry policies on ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands, the research has also interviewed ethnic minority households involved in forest protection and development, the results are as follows in Figure 2:

Figure 2 Elvaluate the Impact of Forest Policies on Income of Ethnic Minorities in Central Highlands (Result by Household Interview, Authors’ Data Collection in 2018)

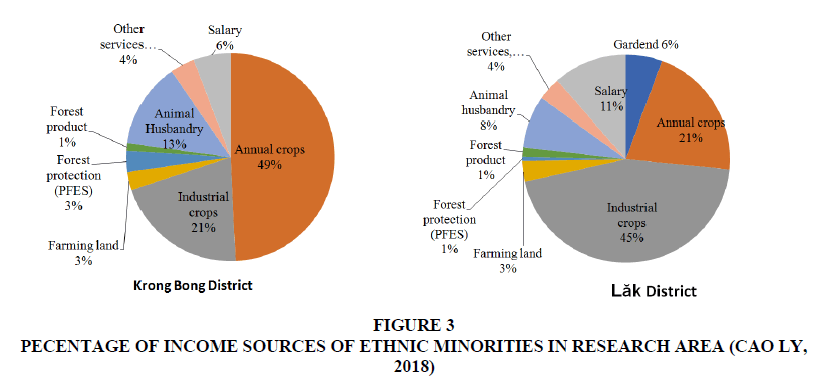

The Impact on Economics

Thus, the reflections from the researches and reports in the Central Highlands are complete and clear that forestry policies have brought income to ethnic minority households. However, this increased income is not really significant in the total income of the household. These income sources come mainly from forest protection contracts and forest environmental services as well as NTFP products, which account for only 0.8 - 1.5% of the total household income (Authors' data collection in 2018). Our survey results are also completely consistent with the research of Cao Ly (2018) in Krong Bong and Lak districts of Dak Lak province.

According to Cao Ly's research, income from forest and forest products, mainly non-timber forest products such as bamboo shoots .., is currently accounting for a low 1.1% (Krong Bong), 1.5% (Lak). Revenues from payment of forest environmental services (PFES) by local households including allocated forests and contracted protection forests from SFEs and national parks in the area and in the two studied districts accounted for 1 - 3% of total income.

However, through the survey, all local people said that PFES although not currently contributing significantly to household economic income, has contributed to encourage households and communities to be more responsible for allocated forest.

Impact on social development

The interview data of 800 ethnic minority households in 2 provinces of Dak Lak and Gia Lai is shown in Table 1 as follows:

| Table 1 The Impact of Forest Policies on the Social Development | |||

| Issues of impact | Impact level (%) | ||

| Reduced | Increasing | remain | |

| Employment on the forest area | - | 100 | - |

| Awareness on the forest protection (effect of shifting cultivation) | - | 97 | 3 |

| Gender equality (women's participation in forest use activities) | - | 55 | 45 |

| Reliability between communities and households about forest protection | - | 90 | 10 |

Thus, it can be seen that forestry policies such as forest land allocation, especially contracting for protection forest have attracted a lot of local labor, which was also summarized above from studies and reports. In the Central Highlands, the forest and forest land area is mainly allocated to SFEs, so the contract between those units and local people in afforestation and forest protection is extremely important. In addition to creating jobs in the forestry sector, these policies also raise people's awareness of the negative impact of shifting cultivation, which demonstrates the communication about protection Forest development has also brought good results. Gender equality also shows that the division of labor between men and women of ethnic minorities, with men often doing things such as forest ranger, logging ... and women often planting and exploiting NTFPs. In addition, social awareness of trust in forest protection among communities and households has also been increased by regulations and conventions developed from forestry policies in Table 2.

| Table 2 The Impact of Forest Policies on Environment | |||

| Issues of impact | Impact level (%) | ||

| Reduced | Increasing | remain | |

| Forest cover | - | 89 | 11 |

| Wood reserves and NTFPs | 2 | 12 | 86 |

| Ability to supply water / maintain flow | - | 91 | 9 |

| Soil erosion/drought/flood | 81 | 3 | 16 |

Impact on Environment

Interview results show that most of local people have a good appreciation of the impact of forestry policies on the environment, especially the policy of contracting for forest protection and forest environmental services that has helped maintain forest cover in Central Highlands, timber reserves and NTFPs. Especially, most of the interviewees assessed the impact of the forest protection and development policy that contributed to reducing phenomena such as soil erosion, drought and flood. It since then has been increasing and maintaining the flow over the years. In addition, all assess that the forestry policies have directly increased the biodiversity to help ensure the livelihoods of the people here.

Negative Impact and limitations

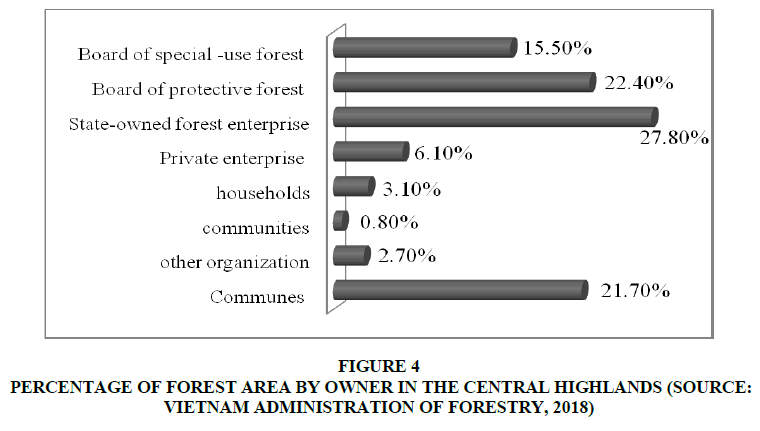

In order to improve the livelihoods of communities associated with forests, the first issue is to give them the right to use and own forests. In the country, 30% of forest land and land is allocated to individuals, households and communities (Sikor et al., 2013); meanwhile, the Central Highlands, which has the highest forest cover in the country with 3,357 million ha of forest and forest land, and has most indigenous people living dependent on the forest, the percentage of forest allocation to households and communities is very low; only 3.1% of the forest area is allocated to households and 0.8% is allocated to communities (totaling about 130,000 ha) (Figure 3) (Vietnam Administration of Forestry, 2018). As such, most indigenous households and communities in the Central Highlands participate in forestry activities mainly indirectly through labor contracts, forest protection contracts, and contract for payment of environmental services. They are not really forest owners and are not directly involved in forest management and service provision activities. In fact, forestry area has not created sustainable livelihoods for ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Percentage of Forest Area by Owner in the Central Highlands (Source: Vietnam Administration of Forestry, 2018)

Small and scattered natural forests are allocated to households, making it difficult or impossible to protect and organize business (each household is allocated from 2-3 ha, some area only 1 ha of land) (Tran et al. 2018).

Access to forest land allocation without community participation leads to unsuitable allocated forest to the needs, capabilities and resources of ethnic minority communities; leading to ineffective management, protection and use of forests (Assigning community to forests which were traditional forests of the neighboring villages not located within the boundaries of their assigned villages, thus preventing them from patrolling and protecting them. It is still considered as a forest of a neighboring village. Or in some places, forest land (forest restoration) has been allocated to the community, is associated with some households upland. Therefore, the households are still being able to cultivate the fields unmanageably (survey results. in Quang Nam, Gia Lai and Dak Lak in 2018); this is also the cause of the failure to implement Decision 304/2005 specifically allocating forest land to ethnic minority communities in the Central Highlands. Especially, the allocation of land to households and communities in the Central Highlands is limited, so very few households own planted forests which have been invested from the 661 program.

Many households received land but were unable to invest in land (100% of the households surveyed in 2018 said that they did not have enough capital to invest in forest production, especially income from forestry also accounting for a small percentage of total household income about 3-5%, surveyed data of the author 2018).

Decreasing economic benefits due to the low unit price of contracting forest protection and the spiralling prices have reduced the interest of the community (80% of the interviewees said that the contract price is too low to conform levels of living, 2018 survey data). This was the same as the study of Nguyen Thi Thu Phuong “the small support for forest protection provided do not allow ethnic minority households to improve their livelihoods, especially if their land is in protected areas where the annual forest protection payments were VND 50,000 per hectare in the national policy before 2007 (though this amount does vary between provinces and districts depending on their conditions and policies)” (Nguyen Thi Thu Phuong and Bob Baulch, 2007).

The benefits that allow people to collect NTFPs in contracted forests are also estimated. This is because their livelihoods are attached to forests and collecting non-timber forest products for food, medicine… is carried out normally even if they are not forest owners. Meanwhile, the SFEs only focus on logging trees.

Some forest areas are contracted and allocated on paper or are not clear in the field, especially where the terrain is complicated. Therefore, the contracted forest is inefficiently protected; in fact the contracted forest areas are lost on a large scale.

The mechanism of policies on forest protection is overlapping and inconsistent, there are many different levels of support in the same area, investment resources are regulated across many sectors, lack of concentration leading to the efficiency of using capital is not high (According to Resolution 30a, it is 300,000 VND/ha/year, according to Decree 75/2015/ND-CP is 400,000 VND/ha/year; the support for board of special-use forest management is 100,000. VND/ha but the norms of contracting special-use forests still have to comply with Resolution 30a and Decree 75/2015 / ND-CP of VND 400,000 / ha / year ....). Specifically, those households residing in the area are both beneficiaries of policy 30a and beneficiaries under Decree 75/2015 / ND-CP, in addition to poor households also receive subsidized rice. This issue has led to the fact that ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands rely on the state for support (Tran et al. 2018a).

The overlap is also reflected in the policy management: All funding sources for the implementation of the forest protection and development policy are regulated by the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development; only funding for forest protection and development under Program 30a is regulated and managed by the Department of Labor and Social Affairs. This overlap makes the integration of forest protection funding sources limited, implemented synchronously and not fully promoted the funding sources.

In fact, local communities in the Central Highlands, especially ethnic minorities, are still on the sidelines of providing forest environment services. Because according to Decree 99/2010, only the right to use forest land such as SFEs, Private Enterprise, households, communities that have been allocated forests, have the right to implement environmental services. Meanwhile, the forest area allocated to households and communities in the Central Highlands is very low, so most of households and communities in Central Highlands have indirectly participated in environmental services through forest protection contracts with SFEs and management boards of protection and special-use forests. This issue leads to the limited access to environmental services and also fewer opportunities to proactively manage protect and use forests of the community.

Since the policy of payment for forest environmental services has been issued, the allocation of forest to households and communities has slowed down. The Communes, SFEs and boards of protective forest and special-use forest want to retain forests to benefit from the policy and only partially subcontract to the people. Meanwhile, the main objective of payment for forest environmental services is to involve the participation of indigenous communities living in watershed area to protect the forest; and the cost of services will contribute to improving income for poor people here.

Conclusion

In general, forestry policies have focused on resolving the relationship between the lives of ethnic minorities and the protection and development of forest resources in the Central Highlands region.

After more than 30 years of implementing policies related to forest management, forest protection and development in the Central Highlands, including: Forest Land Allocation, Forest Protection Contract, implementation of the program 5 million ha reforestation program, Community forestry, benefit from forests and payment for forest environmental services have affected the livelihoods of indigenous ethnic minorities and forest resources in both positive and negative aspects. Benefit from the forest protection and management has not yet contributed to household livelihood income, so it has not attracted people interested in forestry and forest management and protection.

The rate of forest allocation to households and indigenous communities in the Central Highlands is very low, with only 3.9% of the forest area and forestry land. They are not really forest owners and have not been directly involved in forest management and forest environmental services. Therefore, it is necessary to have specific solutions and policies to develop livelihoods for ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands in association with sustainable forest management.

Acknowledgement

This paper was completed within the framework and support of a national project on "Evaluating the effectiveness and impact of forest protection and development policies on ethnic minorities" code number CTDT.17.17/16-20, under Program: National Science and Technology at the 2016-2020 period "Basic and urgent issues on ethnic minorities and ethnic policies in Vietnam until 2030" code number CTDT/16-20.

References

- Cao ly, (2018). Current situation of accessories, benefits from forests and forestry land associated by ethnic minority people in two district of dong kong and lak district, dak lak province. Proceedings of the Workshop on Forest policies in Central Highlands of Vietnam, April, 2018.

- Huy B. (2005). Developing a forest and forest land management model based on ethnic minorities Jrai and Bahnar, Gia Lai province. Report on scientific research topics. Department of Science and Technology of Gia Lai Province, 189p.

- Huy B. (2006). Solutions for establishing benefit sharing in community forest management. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, Hanoi, No. 15 (2006): 48-55

- Huy B. (2007a). Applying a stable forest model in community forest management to sustainably exploit and use timber and firewood in natural forest states. Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, Hanoi, No 8 (2007): 37-42.

- Huy, B., (2007b). Community Forest Management (CFM) in Vietnam: Sustainable Forest Management and Benefit Sharing. Proceedings of the International Conference on Managing Forest for Poor Reduction: Capturing Opportunities in Harvesting and Wood Processing for the benefit of the Poor, from 03 – 06 October 2006 in HCMC Vietnam, FAO, RECOFTC, SNV. ISBN 978-974-7946-97-0, pp 47-60

- Huy, B., (2008). Forest Management and Benefit Sharing in Forest Land Allocation – Case study in the Central Highlands. Proceedings of the forest land allocation forum on 29 May 2008. Tropenbos International Vietnam. Ha Noi, , Thu Do Ltd. Comapany, pp 94-110

- Huy, B. (2009). Increased income and absorbed carbon found in Litsea glutinosa – cassava agroforestry model. APANews (Asia-Pacific Agroforestry Newsletter), FAO, SEANAFE, No. 35(2009): 4-5, ISSN 0859-9742.

- Huy B. (2009a). Community forest management in the Central Highlands. Proceeding of the Conference on Science and Technology of South Central and Central Highlands, June 2009. Scientific and technological applied research projects in service of socio-economic development in the southern central region and Central Highlands in the 2006-2009 period. Ministry of Science and Technology, Dak Lak Provincial People's Committee, pp. 154 - 162.

- Huy B. (2009b). Developing benefit sharing mechanisms in community forest management. Proceedings of the National Workshop on Community Forest Management in Vietnam - Policies and Practices, June 5, 2009. Department of Forestry, IUCN, RECOFTC, Hanoi, pp 39 - 50

- Huy, B., Hung, V. (2011). State of agroforestry research and development in Vietnam. APANews (Asia-Pacific Agroforestry Newsletter), FAO, No. 38(2011): 7-10, ISSN 0859-9742

- Huy B. (2012a). Developing forest carbon measurement and monitoring methods with communities participatory in Vietnam. Journal of Forests and Environment, No. 44 - 45 (2012): 34 - 44.

- Huy B. Vo Hung, Nguyen Duc Dinh. (2012). Assessment of community forest management in the Central Highlands from 2002 to 2012. From reality in Bu Nor village, Quang Tam commune, Tuy Duc district, Dak Nong province. Journal of Forests and Environment, No. 47 (2012): 19 - 28.

- Huy B. (2013). Biometrics and remote sensing model - GIS to identify CO2 absorption of evergreen broadleaf forests in the Central Highlands. Publisher. Science Technology. Ho Chi Minh City, 370p

- Huy, B., Sharma, B.D., Quang, N.V. (2013). Participatory Carbon Monitoring: Manual for Local Staff. Publishing permit number: 1813- 2013/CXB/03-96/TĐ. SNV, HCM city, Viet Nam, 51p.

- Huy, B., (2015). Development of participatory forest carbon monitoring in Vietnam. Paper for the XIX World Forestry Congress on 7-11 September 2015 in Durban, South Africa. Available at http://foris.fao.org/wfc2015/api/file/5528bb539e00c2f116f8e095/contents/0b0ecc8f-4385-4491-a7e0-df8e367d2eaa.pdf

- Huy, B., (2017). Assessment of developing Bu Nor Community Forest Enterprisee (CFE). Technical report. Rainforest Alliance, USA. 29p.

- Huy, B., Tri, P.C., and Triet, T. (2018). Assessment of enrichment planting of teak (Tectona grandis) in degraded dry deciduous dipterocarp forest in the Central Highlands, Vietnam, Southern Forests: a Journal of Forest Science, 80:1, 75-84

- Huy B. (2018). Services ecosystem, forest environment. Tay Nguyen University. 56p.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2005). Decision No. 40/2005 / QD-BNN of the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development dated July 7, 2005, issuing regulations on timber and other forest product exploitation.

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2007). Circular No. 38/2007 / TT-BNN Guiding the order and procedures for forest allocation, forest lease and forest recovery to organizations, households, individuals and village population communities

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2017). Circular No. 12 / VBHN-BNNPTNT, dated November 28, 2017 providing for the main exploitation and utilization of forest products

- Nguyen, T.H., & Catacutan, D. (2012). History of agroforestry research and development in Viet Nam. Analysis of research opportunities and gaps. Working paper 153. Hanoi, Viet Nam: World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) Southeast Asia Regional Program. DOI: 10.5716/WP12052.PDF. 32p.

- Nguyen T.H., & Bob, B. (2007). A review of Ethnic minorit policies and Programs in Vietnam. This paper is a product of the IDS-UoS-CAF Project on ‘Ethnic Minority Development in Vietnam’ financed by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (RES-167-25-0157) and the Department for International Development. 47 p.

- Pham, T.T., Bennett, K., Vũ, T.P., Brunner, J., Le, N.D., et al. (2013). Payments for forest environmental services in Vietnam: From policy to practice. Thematic report 98. CIFOR Bogor, Indonesia, 101p.

- Prime Minister, (1998). Decision No. 661/1998 QD-TTg of the Prime Minister on July 29, 1998 on the objectives, tasks, policies and organization of the implementation of the 5 million hectare reforestation project.

- Prime Minister, (1999). Decree No. 163/1999 / ND-CP on allocation and lease of forestry land to organizations, households and individuals for stable and long-term use for forestry purposes

- Prime Minister, (2001). Decision No. 178/2001 / QD-TTg of November 12, 2001 on the rights, obligations of households and individuals that are assigned, leased, contracted to forests and forestry land. Hanoi.

- Prime Minister, (2005). Decision No. 304/2005 / QD-TTg of the Prime Minister, dated November 23, 2005, on piloting forest allocation and contracting for forest protection for households and communities in ethnic minority villages and villages in the Central Highlands provinces

- Prime Minister, (2010). Decree No. 99/2010 / ND-CP of the Prime Minister dated September 24, 2010 on policies for payment of forest environmental services.

- Sikor, T., Griten, D., Atkinson, J., Huy, B., Dahal, G.R. et al. (2013): Community Forestry in Asia and the Pacific. Pathway to inclusive development. RECOFTC, Bamngkok, Thailand, 112p.

- Tran, Q., Hung., Dang, K., Vui (2017). Short report of project. Committee for Ethnic Affairs.

- Tran, Q., Hung., Dang K., Vui (2018). Short report of project. Committee for Ethnic Affairs.

- Tran, Q., Hung., Dang K., Vui (2018a). Report of survey. Committee for Ethnic Affairs.

- Tran, Q., Hung., Dang K., Vui (2019). Short report of project. Committee for Ethnic Affairs.

- Vietnam Administration of Forestry, (2018). Report on reviewing and adjusting the planning of sustainable protection, restoration and development of forests in the Central Highlands region to 2025, orientation to 2030. Hanoi, 106p.

- Wode, B., & Huy, B. (2009). Study on state of the art of community forestry in Vietnam. GTZ, Hanoi.