Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 4

Transformational Leadership as an Antecedent and SME Performance as a Consequence of Entrepreneurial Orientation in an Emerging Market Context

Enver Rose, Gordon Institute of Business Science

Anastacia Mamabolo, Gordon Institute of Business Science

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to explore the antecedent and consequence of entrepreneurial orientation. The study, anchored on Resource-Based View focuses on how transformational leadership as an antecedent influences entrepreneurial orientation, which consequently contributes to SME performance. A cross-sectional quantitative research approach was used to answer the study’s research question. An online survey data was collected from 158 SMEs originating from South Africa in sub-Saharan Africa. The results show that, transformational leadership is positively associated with entrepreneurial orientation. Both transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation contributed to SME performance. Lastly, entrepreneurial orientation acting as both dependent (on the antecedent) and independent (for the consequence), showed that it is a partial mediator between transformational leadership and SME performance. Since transformational leadership was found to be an important contributor to entrepreneurial orientation. Thus, entrepreneurs should use a transformational leadership style to lead and encourage entrepreneurship within their firms. Entrepreneurship training institutions should incorporate leadership development into their programs.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Orientation, Transformational Leadership, Firm Performance, SMEs.

Introduction

The In a continuously changing and volatile business environment, small and medium businesses (SMEs) become susceptible to failure. The challenge for leadership in this volatile business economy is to align resources and develop entrepreneurial thinking to achieve the organization’s goals (Urban & Govender, 2000). One of the ways to foster entrepreneurial thinking is through entrepreneurial orientation, defined as a strategy making process that provides organizations with a basis for entrepreneurial decisions and actions with the purpose of creating a competitive advantage (Lomberg et al., 2017). Previous research on entrepreneurial orientation has focused on its dimensions (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996), antecedents (Zahra et al., 1999) and outcomes, especially growth and profitability (Rauch et al., 2009; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2005). However, there is still paucity of research on leadership as an antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation (Wales et al., 2013). Entrepreneurial orientation has been distinguished from entrepreneurial processes through its five dimensions, namely-autonomy, innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness and organizational aggressiveness (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Miller, 1983). Transformational leadership refers to the leader moving the follower beyond immediate self-interests through idealized influence (charisma), inspiration, intellectual stimulation, or individualized consideration (Bass, 1999). Wales et al. (2013) motivated research on less explored areas like leadership, to link a small set of the well-developed constructs in explaining and predicting entrepreneurial orientation. Hence, this paper specifically focuses on transformational leadership which may contribute to the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation.

Both entrepreneurial orientation and transformational leadership have been empirically proven to contribute to individual, team and firm performance (Wang et al., 2011; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). Using entrepreneurial orientation as both the independent and dependent variable, this research suggests that it acts as a mediator between transformational leadership and organizational performance (Zahra et al., 1999). This study is a response to few scholars who motivated for more examination of how leadership behaviours and entrepreneurial orientation influence the performance and effectiveness of small businesses (Engelen et al., 2013; Muchiri & McMurray, 2015).

An explanatory quantitative research study was conducted on a sample of 158 SMEs in South Africa located in the Sub-Saharan Africa. Conducting a study in this contextual setting was motivated by Wales et al. (2013) who argued that entrepreneurial orientation remains virtually unexamined in several strategically important countries such as Brazil, India and Russia, as well as in several other country clusters, for example Sub-Saharan Africa. A regression analysis confirmed that transformational leadership contributes to entrepreneurial orientation, which in turn contributes to the SME performance.

The contributions of this study are three-fold. First, the study adds to the scarce research on leadership and entrepreneurship, by showing that transformational leadership is a significant antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation. Second, entrepreneurial orientation is a partial mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and SME performance. Third, the study provides a perspective from an emerging market context which is relatively underexplored. Finally, the research makes implications for entrepreneurs, so they can increase investments in leadership and the entrepreneurial focus of the firm, to improve the overall SME performance.

Literature Review Resource-Based View

This study draws insights from the Resource-Based View (RBV) of the firm to investigate performance and competitive advantage of SMEs by introducing entrepreneurial orientation and transformational leadership as intangible resources (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984). According to Barney (1991), resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable are distinguishing characteristics that can give an SME competitive advantage. A firm will deploy its tangible and intangible resource that are difficult to imitate or duplicate to perform better than competitors (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). The intangible resources of a firm will include processes, specific skills, entrepreneurial orientation, marketing orientation, leadership style and learning orientation (Hall, 1993; Lonial & Carter, 2015) while tangible resources include a firm’s physical assets that are used to convert raw material into product or deliver a service to a customer (Ray et al., 2004; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003).

Entrepreneurial orientation has in several research papers been identified as one of these competencies that will improve SME performance (Abebe, 2014; Lisboa et al., 2016; Semrau et al., 2016). Wiklund & Shepherd (2005) have highlighted the resource intense nature of entrepreneurial orientation as a firm’s entrepreneurial strategy that does not always lead to firm performance due to a shortage of resources, for example finance. Although this argument beyond the scope of the research, it is important for scholars to investigate some of those conditions where entrepreneurial orientation will not lead to firm performance.

Entrepreneurial Orientation

Entrepreneurial orientation as a firm strategy has been a subject of countless research papers (Fernández-Mesa & Alegre, 2015; Lomberg et al., 2017; Semrau et al., 2016; Shirokova et al., 2016). Miller (1983); Covin & Lumpkin (2011) confirmed that entrepreneurial orientation can only exist in an organization in the presence of the three dimensions namely, innovativeness, risk-taking and proactiveness. In the 1990’s competitive aggressiveness and autonomy were added to represent the dimensions that independently and collectively define the domain of entrepreneurial orientation (Covin & Wales, 1983; Lumpkin & Dess 1996). This research will however, focus on innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking, which have been regarded sufficient to represent the entrepreneurial orientation as a one-dimensional construct (Covin & Limpkin, 2011; Covin & Wales, 2012; Miller, 1983).

Innovativeness is the organization’s support of new ideas, creativity, experimentation and newness and/or improvement to processes or products or pursuit of new markets is seen as that organization’s innovativeness (Covin & Lumpkin, 2011; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). Proactiveness is an “opportunity-seeking, forward-looking perspective characterised by the introduction of new products and services ahead of the competition and acting in anticipation of future demand” (Rauch et al., 2009). Risk-taking shows a company’s disposition to pursue untested, unknown and unproven solutions in the pursuit of the unknown (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). These factors will give a firm a competitive advantage, ensuring they can extract monopoly rents giving the firm a superior performance and if the product or service is accepted, good business sustainability (Semrau et al., 2016).

Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership can be traced back to the 1970’s anchored by Burns (1979). This concept of leadership refers to the leader moving the follower beyond immediate selfinterest through the four key dimensions which are Idealised Influence (charisma), Inspirational Motivation, Intellectual Stimulation and Individualised Consideration (Bass, 1990, 1997, 1999). First, idealised influence portrays the socialized charisma of the leader that articulates the organization’s vision and encourage followers to achieve greater goals. Second, inspirational motivational leaders create optimism for the future by setting clear, high standard and achievable goals that need to uplift their followers. Third, intellectual stimulation encourages followers to think creatively and take risks by challenging existing assumptions and solving problems in innovative and unique ways. Finally, individualised consideration describes the individual attention leaders give followers, ensuring to address follower needs for achievement, growth and personal wellbeing (Antonakis et al., 2003; Bass, 1990, 1997, 1999; Judge & Piccol, 2004). These dimensions are important determinants of transformational leadership; however, it might not be possible for a leader to exhibit all the characteristics.

Firm Performance

SME performance in emerging markets have become vital to their survival due to the lack of regulatory support and external competition in the open economy (Le Roux & Bengesi, 2014). Firm performance is a subjective dependent variable as other variables like firm’s industry, organizational strategy, geographic location; age and size determine the organization’s performance (Arshad et al., 2014). Performance measures, unless publicly available would normally be known by the owner-manager of the firm thereby introducing a measure of bias into the result. Additionally, organizational performance is viewed as a reflection of a manager’s ability to successfully manage the organization and his or her ability to successfully perform in their selected role and industry (Chung-Wen, 2008). Alrowwad et al. (2016) confirmed the difficulty in collecting objective data from SMEs and further argued that inappropriate measures can give misleading results on organizational performance and lead to incorrect strategies for performance and sustainability.

Semrau et al. (2016); Chung-Wen (2008) have in their research used organizational growth and profitability as performance indicators. Financial or non-financial measures can be used as proxies for firm performance (Rauch et al., 2009). Financial results such as return on investment, profits, earnings before interest and tax and financial leverage are measures calculated from the firm’s financial statements that indicate the performance and when compared to other financial years, that can represent the growth of the firm. Non-financial measures include firm market share growth, employee satisfaction and company achievement measured against specific set goals (Rauch et al., 2009). This study used Wiklund & Shephered (2018) non-financial indicator growth to measure the performance of SMEs.

Hypotheses

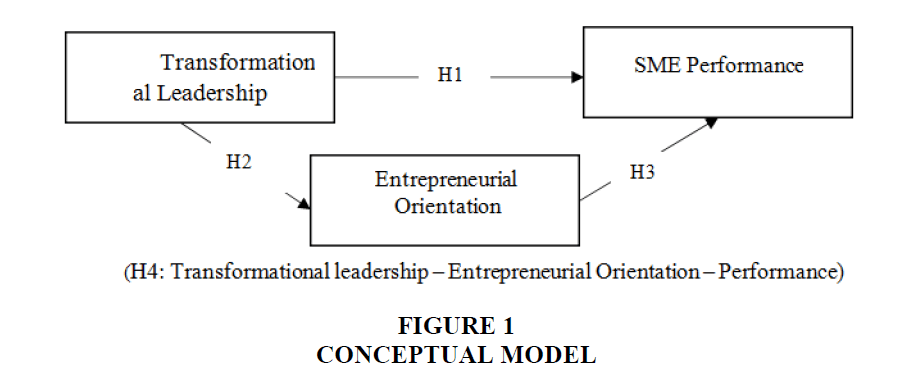

Transformational leadership as antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation. There is consensus that transformational leadership style contributes to entrepreneurial orientation within the firm (Chung-Wen, 2008; Harsanto & Roelfsema, 2015). Some empirical studies focused on the positive association between transformational leadership and innovation which is one of entrepreneurial orientation dimensions (García-Morales et al., 2012; Matzler et al., 2008). Muchiri & McMurray (2015) argued that transformational leaders of small businesses would influence entrepreneurial orientation and behaviours of employees through encouraging in-depth intellectual processing, questioning norms, concepts, practices and processes. Through inspirational motivation (Bass, 1990, 1991, 1997), transformational leaders would encourage employees to take risks, be creative and innovative, which are critical elements in entrepreneurial orientation. Given the view, the study hypothesis shown in Figure 1 is that:

H1: Transformational leadership is positively related to entrepreneurial orientation.

Transformational leadership and SME performance

Transformational leadership style has greater effect in improving employee’s performance when compared to other leadership styles, resulting in improved business performance (Aziz et al., 2013). Another empirical study of 406 SMEs in Taiwan showed that transformational leadership is more correlated to performance than transactional and passiveavoidant leadership styles (Chung-Wen, 2008). This suggests that the trusting environment created by transformational leaders creates an environment where employees do more than what is expected, thereby improving firm performance (Engelen et al., 2013). The studies by Joo & Lim (2013); Zhu et al. (2005) show a positive correlation between employee job satisfaction and transformational leadership in a firm, results were based on 427 employees and 170 firms respectively. These studies confirm the notion that transformational leadership improves the performance of a firm, with the company CEO playing a vital role in achieving the performance. On this note, the study hypothesizes that:

H2: There is a positive relationship between transformational leadership and SME performance.

Entrepreneurial Orientation and SME Performance

Various researchers have studied and proven the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance (Abebe, 2014; Lisboa et al., 2016; Semrau et al., 2016). In this fast changing and dynamic market, organizations need to develop agile strategies that would see changes in products as customers’ need change. This dynamism of the market will result in a short product life that, through the adoption of entrepreneurial orientation will ensure continuous innovation and firm sustainability. Some of the smaller firms consider business continuity as performance (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). There is; however, an agreement that appropriate management of entrepreneurial orientation within the organization will result in sought after benefits (Engelen et al., 2013). Therefore, this study suggests that:

H3: There is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance.

Transformational Leadership, Entrepreneurial Orientation and SME Performance

Wiklund & Shepherd (2005) suggested a configurationally approach, which is a threeway interaction model to understand entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. They argued that this is contrary to the two-way approach contingency model which was previously used in entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance research. In the same vein, this study brings together transformational leadership, entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance. One of the few empirical studies found that transformational leadership contributed to entrepreneurial orientation, which ultimately resulted in improved performance (Chung-Wen, 2008). Moreover, a study by Engelen et al. (2013) found that transformational leadership positively affects the entrepreneurial orientation-performance relationship in a firm, irrespective of the national setting. Using the configurationally approach, entrepreneurial orientation acts as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and SME performance. Based on these discussions, the study hypothesizes that:

H4: Entrepreneurial orientation mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and SME performance.

Methodology Research

The business case of this study is motivated by the low entrepreneurial activity, SME challenges, unemployment and lack of job creation in South Africa, which is one of the big economies in Africa. The 2018 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report highlights that South Africa’s total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) as 11% in 2017, placing South Africa 27 out of 54 efficiency-driven economies that have an average of 14.9%. TEA is a percentage measure of the adult population who initiated a business venture or have been operating a business for less than 42 months (GEM, 2018). Moreover, a previous report by Herrington et al. (2017) also illustrates that South Africa has the lowest entrepreneurial activities when compared to other countries in Africa. It is the opinion of many industry experts that the small business industry is over-regulated thus, constraining SMEs who are focusing their energy on surviving in the sector. Business leaders can benefit from understanding how an entrepreneurial strategy can benefit their SMEs. Transformational leaders, using their charisma can successfully communicate the organization’s goals and get buy-in from their followers (Banks et al., 2016). With entrepreneurial strategic orientation and relevant leadership, these small companies could be better placed to exploit opportunities that exist in their environment.

Sample and Data Collection

The population of this research is SMEs across varying sectors and industries in the South African market. A database of South African SMEs was acquired from an organization that has contact details of SMEs from different sectors and regions in South Africa. The company that provided the contact details has the permission of all the listed SMEs in the database to use their contact details in market research. The unit of analysis for this research is SME in South Africa. An online survey was directed at senior manager and/or directors of the firms, who have access to information required for this study. The senior managers or directors were selected because entrepreneurial orientation is a firm-level strategy that would be developed by the senior management as the firm’s strategic direction (Ireland et al., 2003). The sample frame contained 2,550 SMEs from different sectors and from different regions in South Africa.

Data for this mono-method research were collected using a self-administering internetbased survey. Data collection was done using an open-ended self-administered questionnaire completed by owner-managers (entrepreneurs) of the various SMEs. This study was cross sectional. Saunders and Lewis (2012) confirmed that a cross-sectional study will normally employ a survey strategy and produce quantitative data. The survey was distributed during the last week of July 2018 and was closed at the end of September 2018 after receiving 164 responses. The internet-based survey was used because it reaches a wider population of respondents in a shorter period.

Independent Variables

Transformational leadership: A review of the literature into leadership confirmed the decision to use a Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ form 6S) adapted from Avolio & Bass (2004); Vinger & Cilliers (2006); Muenjohn & Armstrong (2008). The measurement instrument was anchored in a five-point Likert scale that ranged from 1=Not at all to 5=frequently.

Entrepreneurial orientation: The second section of the survey focussed on entrepreneurial orientation, using the Entrepreneurial Orientation Questionnaire (EOQ). The EOQ scale was adapted from Lumpkin & Dess (1996); Hughes & Morgan (2007); (Shirokova et al., 2016). The questions were anchored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from, 1=Strongly Disagree, 2=Disagree, 3=Partially Disagree, 4=Neutral, 5=Partially Agree, 6=Agree and 7=Strongly Agree.

Dependent Variable

Firm performance: As a multidimensional construct, performance of a firm is very difficult to measure; especially as owner-managers feel negative performance may reflect on his or her leadership quality and ability to sustain a business, making this a subjective measure (Aziz et al., 2013; Chung-Wen, 2008; Vora et al., 2012). As this construct was self-reported, there may have been a measure of bias in their responses. The most common measure of performance is financial this however is difficult to obtain in small unlisted entities. Therefore, firm performance was measured as a non-financial construct using the scale of Wiklund & Shepherd (2005). The scale used in this research was anchored in a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1= much better than competitors to 5=much worse than competitors.

Data Analysis

After data collection, a Total of 164 responses were received. This number was reduced to 158, by removing firms that did not fit the description of SME in terms of number of employees and the respondent’s level in the organization. Since the instruments for entrepreneurial orientation, transformational leadership and SME performance already existed, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was analysed for validity and the reliability of the instrument. The global fit indices that were used to assess the CFA model are Chi-square (2), degree of freedom (df), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) and normed fit index (NFI). Multiple regression analysis was performed using add-in software in SPSS named PROCESS V3 to test the hypothesized relationships (Hayes, 2018). The PROCESS algorithm was developed by Hayes and conducts the regression and inferences in SPSS. Before performing the multiple regressions, further assumptions for the test had to be satisfied according to Pallant (2010). The sample size of 158 with two independent variables has been established to be acceptable to perform the multiple regression test. Univariate outliers were analyzed, and extreme outliers were removed. Normality of the data has been established and all the constructs’ skewness and kurtosis were found to be within ±2 (George & Mallery, 2010). Multicollinearity was examined using the normal regression, which revealed that both the variance inflation factor (of 1.152) and tolerance (of .868) ruled out the high intercorrelations between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation.

Results Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the biographic profile of the respondents and the SMEs. Most of the respondents were male, 75.9% (n=120) of the 158 total respondents. With regards to firm’s age, the data shows the majority of the firms surveyed, n=103, were in existence between 11 and 20 years, the number equated to 65.2% of the total respondents (n=158). Firms that have been in existence for more than 20 years accounted for 24.7% (n = 39) and the remaining firms with less than ten years of operation accounted for 5.1%. Of the 158 respondents, 64.6% (n=102) of firms employed less than 50 employees, firms with more than 100 employees amounted to 19.6% (n=31) and firms employing between 50 and 100 employees represented 15.8% (n=25) of the 158 respondents. These employees were from different industries, with the highest representation from the services industry with 39.2% (n=62) followed by engineering with 24.1% (n=38) then manufacturing with 15.8% (n=25) (Table 1).

| TABLE 1: Descriptive Statistics | |||

| Biographic variables | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 120 | 75.9 |

| Female Total | 38 | 24.1 | |

| 158 | 100 | ||

| Age | Less than 5 years | 8 | 5.1 |

| Between 5 and 10 years | 8 | 5.1 | |

| Between 11 and 20 years | 103 | 65.2 | |

| More than 20 years | 39 | 24.7 | |

| Total | 158 | 100 | |

| Number of employees | Less Than 50 | 102 | 64.6 |

| Between 50 and 100 | 25 | 15.8 | |

| More than 100 | 31 | 19.6 | |

| Total | 158 | 100 | |

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Test

Since the variables that were used in this study originated from existing instruments, CFA was deemed to be an appropriate statistical tool for analysing the validity and reliability of the instrument. For example, the entrepreneurial orientation scale was existing from Hughes and Morgan (2007). Following Miller (1983), entrepreneurial orientation was viewed as onedimensional construct. The model summary showed that entrepreneurial orientation, GFI=0.950, CFI=0.978, NFI=0.944, RMSEA=0.060, χ2 (d(f)) = 36.072 (23). The reliability score is α=0.860 consisting of nine measurement items. All items were retained.

The transformational leadership construct was based on Vinger & Cilliers (2006), Avolio & Bass (2004); Muenjohn & Armstrong (2008). CFA showed a significant model with GFI=0.982, CFI=1.00, NFI=0.929, RMSEA=0.00, χ2 (d(f)) = 11.835 (19). The following items were removed from the model: I express with a few simple words what we could and should do; I enable others to think about old problems in new ways; I tell others what to do if they want to be rewarded for their work and I provide others with new ways of looking at puzzling things. The final reliability score is α = 0.709 with eight measurement items.

Finally, SME performance construct consisted of profitability and growth measurement items. The model for profitability indicators was not identified, leaving an option to use the nonfinancial growth indicators. This is because some of the SMEs might not have accurate financial indicators. The CFA results shows that non-financial model was significant with GFI=0.987, CFI=0.992, NFI=0.984, RMSEA=0.073, χ2 (d(f))=5.553 (3). The reliability score of α=0.838 for the non-financial indicators.

Correlation Results

Pearson’s correlation coefficient displayed in Table 2 was used to determine the relationship between transformational leadership, entrepreneurship and SME performance of SME. The results show a significant relationship between transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation (r=0.363, p<0.01). Entrepreneurial orientation was significantly and positively associated with SME performance (r=0.337, p<0.01). Finally, transformational leadership was found to be significantly positively correlated with business performance (r=0.297, p<0.01). Although the correlations are low, the relationships are significant. Transformational leadership and entrepreneurial orientation were found to have higher correlations than entrepreneurial orientation/transformational leadership and SME performance relationship.

| Table 2: Correlation Between The Variables | |||||

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformational Leadership | 4.2 | 0.41 | 1 | ||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | 5.6 | 0.76 | .363** | 1 | |

| SME performance | 3.3 | 0.83 | .297** | .337** | 1 |

| **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). n= 159 | |||||

Hypothesis Testing: Regression Analysis

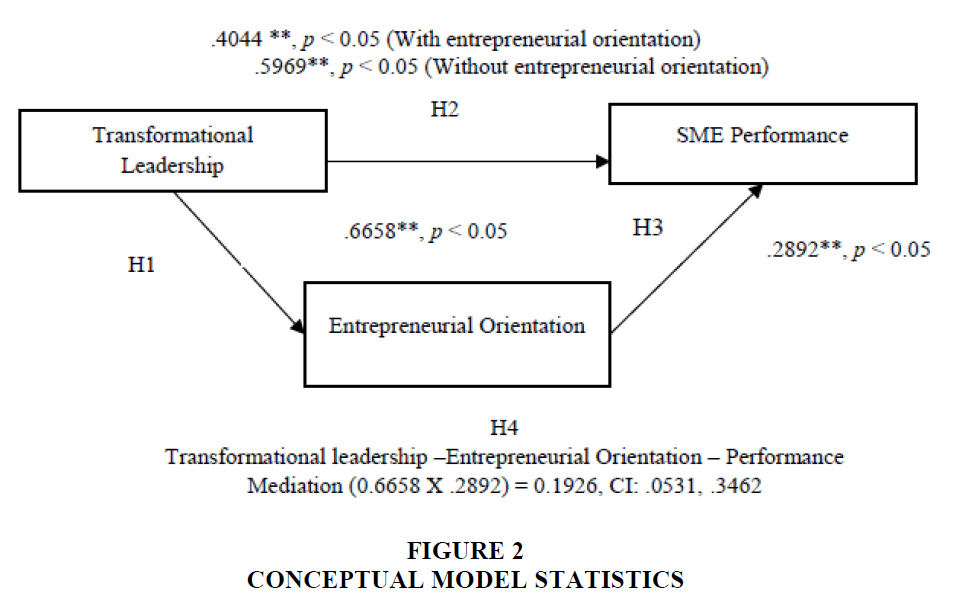

Table 3 shows the results of transformational leadership as an antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation. Regression analysis results with R=0.3629, R2=0.1317, p<0.05, indicate that the model is significant. Co-efficient values illustrate that transformational leadership with β=0.6658, SE=0.1365, p=0.000 is a significant predictor of entrepreneurial orientation.

| Table 3: Transformational Leadership As An Antecedent Of Entrepreneurial Orientation | ||||||

| Dependent variable: Entrepreneurial orientation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Beta | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | 2.8054** | 0.5759 | 4.8716 | 0 | 1.6679 | 3.9428 |

| Transformational | .6658** | 0.1365 | 4.8793 | 0 | 0.3963 | 0.9354 |

| Model summary F = 23.8080 R = .3629 R2 = .1317 df1 = 1.0000 df2 = 157.0000 p = 0.000 MSE=0,5052 | ||||||

| Notes: ** p < 0.05 | ||||||

The model summary of transformational leadership and SME performance in Table 4, is significant with R=0.2969, R2=0.0881, p<0.05. A further analysis of the co-efficient output in Table 4 demonstrates that transformational leadership (β=0.5969, SE=0.1532, p=0.0001) is a significant predictor of SME performance.

| Table 4: Transformational Leadership And Performance | ||||||

| Dependent variable: SME performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Beta | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | 0.7736 | 0.6467 | 1.1962 | 0.2334 | -0.5038 | 2.0509 |

| Transformational | 0.5969** | 0.1532 | 3.8953 | 0.0001 | 0.2942 | 0.8996 |

| Model summary F = 15.1733 R = .2969 R2 = .0881 df1 = 1.0000 df2 = 157.0000 p = 0.001 MSE = 0,6371 | ||||||

| Notes: ** p < 0.05 | ||||||

Regression outputs displayed in Table 5 and 6 determine if entrepreneurial orientation will mediate the effect of transformational leadership on SME performance. When the mediation variable (entrepreneurial orientation) is introduced in the model, the findings demonstrate that entrepreneurial orientation is a significant predictor of SME performance (β=0.2892, SE=0869, p<0.05) thus supporting the mediational hypothesis. It should be noted that transformational leadership reduced from β=0.5969 to β=0.4044, but was still significant with p=0.0122, suggesting that there is a partial mediation. Partial mediation happens when β of the independent variable reduces but continues to be a significant predictor of the dependent variable after the introduction of the mediator variable (Wood et al., 2008). Approximately 15% (R2=0.1486) of the variance in SME performance was accounted for by transformational leadership and the mediation of entrepreneurial orientation. The indirect effect shown in Table 6 was tested using a percentile bootstrap estimation approach with 10000 samples (Shrout & Bolger, 2002), implemented with the PROCESS macro Version 3 (Hayes, 2018). These results indicate that the indirect coefficient (entrepreneurial orientation) is significant, thus, β=0.1926, SE=0.0749, 95% CI=0.0531, 0.3462. Transformational leadership is associated with performance that was approximately .19 higher as mediated by entrepreneurial orientation.

| Table 5: Sme Performance As A Consequence Of Transformational Leadership And Entrepreneurial Orientation | ||||||

| Dependent variable: SME performance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Beta | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | -0.0378 | 0.6726 | -0.0561 | 0.9553 | -1.3663 | 1.2908 |

| Transformational | 0.4044** | 0.1594 | 2.5366 | 0.0122 | 0.0895 | 0.7193 |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.2892** | 0.0869 | 3.3289 | 0.0011 | 0.1176 | 0.4608 |

| Model summary F = 13.6146 R = .3855 R2 = .1486 df1 = 2.0000 df2 = 156.0000 p = 0,000 MSE = .5986 | ||||||

| Notes: **p < 0.05 | ||||||

| Table 6 : Mediation Effect | ||||||

| Indirect effect(s) of transformational leadership on SME performance through entrepreneurial orientation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | 0.1926 | 0.0749 | 0.0531 | 0.3462 | 1.6679 | 3.9428 |

Figure 2 presents the summary of the tested hypotheses and their statistical findings.

Discussion

Drawing insights from the Resource-Based View of the firm (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991; Wernerfelt, 1984), this study determines how transformational leadership influence entrepreneurial orientation which consequently contributes to the organizational performance. A finding that transformational leadership is significantly associated with entrepreneurial orientation is consistent with the existing literature (Chung-Wen, 2008; García-Morales et al, 2012; Matzler et al., 2008). This is due to the notion that transformational entrepreneurs may encourage their employees to be proactive and achieve the set organizational goals. Also, through transformational leadership, entrepreneurs are able to have intellectual stimulations with their employees, resulting in new ideas or innovations (Muchiri & McMurray, 2015). Since transformational leaders offer inspiration to their followers (Bass, 1990, 1997, 1999), they will inspire employees to take risks and design new processes that will improve the competitive advantage of the firm. Therefore, this study makes a contribution to the research on entrepreneurial orientation and leadership by showing that transformational leadership is a significant antecedent (Wales et al. 2013).

The study’s findings illustrate that transformational leadership is associated with SME performance. These results are confirmed by previous scholars within the SMEs context who argue that the presence of transformational leaders will contribute to the individual, team and SME performance (Joo & Lim, 2013; Chung-Wen, 2008; Zhu et al., 2005). Based on these results, entrepreneurs should not only focus on the technical (like operations management) aspects of their firms, but also on developing their transformational leadership attributes, which will contribute to the firm’s performance. In the context of this study, non-financial indicators are suitable measures for SME performance, contrary to Ranch et al. (2009) who argued that financial indicators may yield more significant results than non-financial. This may be due to the notion that in developing market contexts financial indicators are scarce and SME owners may be reluctant to disclose their quantitative financial figures (Alrowwad et al., 2016). On this note, further studies on SME performance conducted in contexts with limited quantitative financial data, can use the non- financial data to measure performance.

It has been widely agreed that entrepreneurial orientation contributes to the SME performance (Abebe, 2014; Lisboa et al., 2016; Semrau et al., 2016; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003). This study’s findings demonstrate that it is the case for SMEs that are in emerging markets. The findings suggest that entrepreneurs could use entrepreneurial orientation strategy as a way of growing their businesses despite the challenging business environment and institutional inadequacies they encounter (GEM, 2018; Herrington et al., 2017). Their innovativeness, reactiveness and risk taking can serve as unique intangible resources that may lead to a better advantage over their competitors (Wernerfelt, 1984; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003)

Finally, a configurational approach demonstrates that entrepreneurial intention can be a dependent variable of transformational leadership and an independent variable for SME performance. According to the study’s finding entrepreneurial orientation is a partial mediator that explains the relationship between transformational leadership and firm performance. This study responds to the call by scholars to focus on the relationship between these three constructs, so as to enhance the research on entrepreneurial orientation (Engelen et al., 2013; Wales et al., 2013).

Therefore, by showing this transformational leadership - entrepreneurial orientation - SME performance relationship, this research contributes to the entrepreneurship and leadership literature.

Conclusion, Implications And Limitations

The aim of this study is to investigate transformational leadership as an antecedent and SME performance as an outcome of entrepreneurial orientation. The findings confirmed that transformational leadership contributes to entrepreneurial orientation. And that, entrepreneurial orientation contributes to the overall performance of the firm, especially non-financial. Further, the results suggest that entrepreneurial orientation is a partial mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and performance.

The practical implications for the study are as follows: first, entrepreneurs need to use transformational leadership within their firms, as a way of encouraging the entrepreneurial orientation. Second, entrepreneurial orientation is a firm wide phenomenon that should normally be implemented by all employees in the firm. As a strategic orientation towards entrepreneurship, it would therefore require firm’s adoption of an entrepreneurial culture. Operative implementation of an entrepreneurial orientation strategy would indicate leaders’ willingness to involve employees in setting and fulfilling the goals of the organization. Finally, the entrepreneurship training institutions should incorporate leadership development programmes for entrepreneurs.

Every research has limitations, therefore the three limitation of this research, like most quantitative research, relates to data collection and analysis. The sample size was small, and a cross-sectional study does not account for changes over time or the firm’s strategic intent over the period. Therefore, future research should expand on this configurationally approach by investigating transformational leadership as a moderator of entrepreneurial orientation and performance over time using larger sample sizes.

References

- Abebe, M. (2014). Electronic commerce adoption, entrepreneurial orientation and small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) performance. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 21(1), 100-116.

- Alrowwad, A., Obeidat, B. Y., Tarhini, A., & Aqqad, N. (2016). The impact of transformational leadership on organizational performance via the mediating role of corporate social responsibility: a structural equation modeling approach. International Business Research, 10(1), 199.

- Antonakis, J., Avolio, B.J., & Sivasubramaniam, N. (2003). Context and leadership: An examination of the nine- factor full-range leadership theory using the multifactor leadership questionnaire. Leadership Quarterly 14(3).

- Arshad, A.S., Rasli, A., Arshad, A.A., & Zain, Z.M. (2014). The impact of entrepreneurial orientation on business performance: a study of technology-based SMEs in Malaysia. Procedia-Social and behavioral sciences, 130(1996), 46-53.

- Avolio, B.J., & Bass, B.M. (2004). Multifactor leadership questionnaire (MLQ). Mind Garden, 29.

- Aziz, R., Abdullah, H., Tajudin, A., & Mahmood, R. (2013). The effect of leadership styles on the business performance of SMEs in Malaysia. International Journal of Economics Business and Management Studies, 2(22), 2226-4809.

- Banks, G.C., McCauley, K.D., Gardner, W.L., & Guler, C.E. (2016). A meta-analytic review of authentic and transformational leadership: A test for redundancy. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(4), 634-652.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Bass, B.M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational

- Dynamics, 18(3), 19-31.

- Bass, B.M. (1997). Does the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist, 52(2), 130-139.

- Bass, B.M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9-32.

- Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Cant, M., & Wiid, J. (2013). Establishing the challenges affecting South African SMEs. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 12(6), 707-716.

- Chung-Wen, Y. (2008). The relationships among leadership styles, entrepreneurial orientation, and business performance. Managing Global Transitions, 6(3), 257.

- Covin, J.G., & Lumpkin, G.T. (2011). Entrepreneurial orientation theory and research: Reflections on a needed construct. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 35(5), 855-872.

- Covin, J.G., & Wales, W.J. (2012). The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship: Theory and practice, 36(4), 677-702.

- Engelen, A., Gupta, V., Strenger, L., & Brettel, M. (2013). Entrepreneurial Orientation, firm performance, and the moderating role of transformational leadership behaviors. Journal of Management, 41(4), 1069-1097.

- Fernández-Mesa, A., & Alegre, J. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation and export intensity: Examining the interplay of organizational learning and innovation. International Business Review, 24(1), 148-156.

- García-Morales, V.J., Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M.M., & Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. (2012). Transformational leadership influence on organizational performance through organizational learning and innovation. Journal of Business Research, 65(7), 1040-1050.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, 17.0 update (10th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. (2018). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2017/2018.

- Hall, R. (1993). A framework linking intangible resources and capabiliites to sustainable competitive advantage.

- Strategic management journal, 14(8), 607-618.

- Harsanto, B., & Roelfsema, H. (2015). Asian leadership styles, entrepreneurial firm orientation and business performance. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 26(4), 490-499.

- Hayes, A.F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression based approach (2nd ed). New York; London: The Guilford Press.

- Herrington, M., Kew, P., & Mwanga, A. (2017). South Africa report: Can small businesses survive in South Africa.

- Global Entrepreneurship monitor 2016-17.

- Ireland, R.D., Hitt, M.A., & Carey, W.P. (2003). A model of strategic entrepreneurship: The construct and its dimensions David g. Sirmon. Journal of Management, 29(6), 963-989.

- Joo, B.K., & Lim, T. (2013). Transformational leadership and career satisfaction. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(3), 316-326.

- Judge, T.A., & Piccol, R.F. (2004). Transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analytic test of their relative validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(5), 755-768.

- Lisboa, A., Skarmeas, D., & Saridakis, C. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation pathways to performance: A fuzzy-set analysis. Journal of Business Research, 69(4), 1319-1324.

- Lomberg, C., Urbig, D., Stöckmann, C., Marino, L.D., & Dickson, P.H. (2017). Entrepreneurial orientation: The dimensions’ shared effects in explaining firm performance. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 41(6), 973-998.

- Le Roux, I., & Bengesi, K.M.K. (2014). Dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation and small and medium enterprise performance in emerging economies. Development Southern Africa, 31(4), 606-624.

- Lumpkin, G.T., & Dess, G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135-172.

- Matzler, K., Schwarz, E., Deutinger, N., & Harms, R. (2008). The relationship between transformational leadership, product innovation and performancein SMEs. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 21(2), 139- 151.

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770-791.

- Muchiri, M., & McMurray, A. (2015). Entrepreneurial orientation within small firms: A critical review of why leadership and contextual factors matter. Small Enterprise Research, 22(1), 17-31.

- Ray, G., Barney, J.B., & Muhanna, W.A. (2004). Capabilities, business processes, and competitive advantage: choosing the dependent variable in empirical tests of the resource?based view. Strategic management journal, 25(1), 23-37.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Lumpkin, G.T., & Frese, M. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 761-787.

- Saunders, M., & Lewis, P. (2012). Doing Research in Business & Management: An Essential Guide to Planning your Project. Essex: Pearson and Education Limited.

- Semrau, T., Ambos, T., & Kraus, S. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance across societal cultures: An international study. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1928-1932.

- Shirokova, G., Bogatyreva, K., Beliaeva, T., & Puffer, S. (2016). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in different environmental settings: Contingency and configurationally approaches. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 23(3), 703-727.

- Shrout, P.E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological methods, 7(4), 422.

- Urban, B., & Govender, T. (2000). Cultivating an entrepreneurial mind-set through transformational leadership: A focus on the corporate context. Managing Global Transitions, 15(2), 123-143.

- Vora, D., Vora, J., & Polley, D. (2012). Applying entrepreneurial orientation to a medium sized firm. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 18(3), 352-379.

- Vinger, G., & Cilliers, F. (2006). Effective transformational leadership behaviours for managing change. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 4(2), 1-9.

- Wales, W.J., Gupta, V.K., & Mousa, F.T. (2013). Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: An assessment and suggestions for future research. International Small Business Journal, 31(4), 357-383.

- Wang, G., Oh, I.S., Courtright, S.H., & Colbert, A.E. (2011). Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of research. Group & Organization Management, 36(2), 223-270.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource?based view of the firm. Strategic management journal, 5(2), 171-180.

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1307-1314.

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2005). Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(1), 71-91.

- Wood, R.E., Goodman, J.S., Beckmann, N., & Cook, A. (2008). Mediation testing in management research: A review and proposals. Organizational research methods, 11(2), 270-295.

- Zahra, S.A., Jennings, D.F., & Kuratko, D.F. (1999). The antecedents and consequences of firm-level entrepreneurship: The state of the field. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(2), 45-65.

- Zhu, W., Chew, I.K.H., & Spangler, W.D. (2005). CEO transformational leadership and organizational outcomes: The mediating role of human-capital-enhancing human resource management. Leadership Quarterly, 16(1), 39-52.