Research Article: 2020 Vol: 24 Issue: 4

Understanding Entreprenuerial Intention: A Mediation Effect of Entreprenuerial Motivation on Perceived Desirability to New Venture Creation Intention

Yussi Ramawati, Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis, Unika Atma Jaya Jakarta Indonesia

Prof.Ach. Sudiro, Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia

Fatchur Rochman, Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia

Mugiono, Fakultas Ekonomi dan Bisnis, Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia

Abstract

The concept of entrepreneurship can attract the attention of the government to develop the creative industry sector so that it can participate in improving the country's economy. Creative economic entrepreneurship can be explored from the intentions of citizens in entrepreneurship. The intention to form a new business is high when individuals have entrepreneurial motivation and feel the perceived desirability. Meanwhile, entrepreneurial motivation is determined by how much he perceived desirability. Thisstudy examinesthe effect of perceived desirability and entrepreneurial motivations on the create new venture intentions. In addition, this study also examines the influence of perceived desirability on entrepreneurial motivation. The study was conducted in Kalimantan with 196 respondents. Test results with partial least square prove that all research objectives are proven. This research proved that entrepreneurial motivation can mediate the relationship between perceive desirability and create new venture intentions.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Motivation, Perceived Desirability, New Venture Creation.

Introduction

The creation of new business through creative industries has become a trend and phenomenal in various countries that can make a significant contribution to the level of economic growth of a country. The creative industry was first introduced in Australia in 1994. The study of the creative industry shifted to the creative economy, the concept of the creative economy was further studied and developed in the UK in 1998, England was the first country in the world to learn about the creative economy by providing more explanation in about the implications of the creative industries that create new entrepreneurs. The current entrepreneurship model in Asia is Japan and South Korea. The creation of new business is supported by government policies that lead to business independence so that access to capital from the domestic investment is easier and more promising compared to investment from foreign parties (He et al., 2019). In the context of creating business in Indonesia, Go-Jek Indonesia proves that the pioneering motorcycle taxi business which is local wisdom from Indonesia has been successfully adapted into a unicorn-scale business. Even Go-Jek is now embracing entrepreneurs from Bangalore India and carrying out its activities in various countries in Asia especially Southeast Asia which can rely on motorized vehicles to fight traffic congestion (Coupez et al., 2016).

The success of creating a new business cannot be separated from the intention. The theoretical framework which is the basis for the theory of desire for entrepreneurship was developed from Fishbein & Ajzen (1975) Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), Azjen (1991) The theory of planned behavior and Saphero (1982) Theory of SEE. In the SEE perspective, entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by desires, perceptions of conformity and a tendency to act. This study develops the framework of Saphero (1982) which states that the perceived desirability affects the intentions of creating new ventures. In contrast to Shapero (1982) perceived desires affect interest in creating new business when perceived desires can provide entrepreneurial motivation.

Previous studies examining the relationship between perceived desirability and entrepreneurial interest show inconsistent results. Alhaj, (2011); Zhang (2014) prove that entrepreneurial intentions are influenced by the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, Fitzmmons (2011); Alfonso-Guzman et al. (2012); Garba et al. (2014), are related to desires, perceptions of conformity, and tendencies to act as factors. that determines entrepreneurial intentions. Segal et al. (2005); Alhaj (2011); Zhang et al. (2014); Solviek (2012); Solviek (2014); Boukamcha (2015); Yatribi (2016); Esfandiar (2016). found that Perceived Desirability had a significant influence on the formation of Entrepreneurial Intention while in research conducted by Fitzsimmons (2011); Garba (2014); Kajiun (2015) found that Perceived Desirability did not significantly influence the formation of Entrepreneurial Intention.

This research is expected to be able to contribute theories about the desire to create new businesses as the development of Shapero (1982). A new perceived desire will affect the desire to create a new business if the desired desire can encourage entrepreneurial motivation.

Literature Review

New Venture Creation Intention

The intention theory was first introduced by Fishbein & Ajzen (1975) which was later developed through the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) by explaining intentions on customer behaviour. Subsequent research Ajzen & Fishbein (1980) say that intention is the main predictor of human behaviour. Intention refers to the willingness or readiness to engage in the behaviour considered (Han & Kim, 2010). Intention is also an element that dominates motivational factors in influencing individual behaviour. Intention is closely related to real behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Kruger, 2000).

The intention to create a new business is the extent to which someone is interested in having a plan to set up his new business. Intention is the only best predictor of every planned behavior, including entrepreneurship. Understanding the antecedents of intentions increases our understanding of the intended behavior. Attitudes influence behavior by its impact on intention. Intentions and attitudes depend on the situation and people. Thus, the intention model will predict better behavior than individual variables (for example, personality) or situational (for example, employment status). Predictive power is very important for a better post hoc explanation of entrepreneurial behavior; intention models provide superior predictability. (2) Personal and situational variables usually have an indirect influence on entrepreneurship through the influence of key attitudes and general motivation to act. For example, role models will affect entrepreneurial intentions only if they change attitudes and beliefs such as the perception of self-efficacy. An intention-based model illustrates how exogenous influences (for example, perceptions of resource availability) change intentions and, ultimately, business creation. (3) The versatility and robustness of the intention model supports the wider use of a comprehensive process model, driven by theory (Kruger, 2000).

Perceived Desirability and Entrepreneurial Motivation

Perceived desirability for entrepreneurial action in the SEE model is used to explain entrepreneurial intentions. Perceived desire refers to the level of attractiveness of new business for entrepreneurs. Perception of desirability goals and inner appreciation and appreciation from the outside obtained after achieving objective behavior affects personal attitudes (Krueger, 2000). In addition, in harmony with social norms, the opinions of family, friends, and colleagues about entrepreneurial business felt by entrepreneurs internalized in perceived desirability. Shapero, (1982) suggested that each person with perceived desirability as a high level of importance with enthusiasm with the desire for new ventures. Desires that are felt as related to personal values and career choices. Desire has an important role as an initial attitude that determines a person for the growth of entrepreneurial intentions related to initial consideration earlier to achieve what is desired.

In this research, the writer uses the concept of perceived desirability as a predictor variable that has a direct influence on entrepreneurial intentions, but it is also suggested that the Perceived Desirability variable can also affect directly or indirectly. Indirectly influence through mediation of entrepreneurial motivation towards new venture creation intention as stated by (Swierczek, 2003; Taormina, 2007; Solesvik, 2013). The author tries to use the theoretical concepts proposed by Saphero, (1982) by testing entrepreneurial motivation as a mediating / intervening variable that is using the SEE concept model. Based on the description, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Motivation is important because motivation involves energy, direction, perseverance, and intention. Objectives and motives play a role in predicting human behavior. In the perspective of plan behavior, motivation encourages action. It shows the relationship between intention, motivation, and behavior. Motivation can be a stimulus to change latent intentions that encourage entrepreneurship and can be a missing link between intention and action. This implies that the attitudes and goals that underlie entrepreneurial motivation must bring up entrepreneurial intentions (Edelman et al., 2010). Motivation is the drive to work hard to get many things such as profit, freedom, personal dreams, and independence. Motivation is an incentive for individuals to work hard to generate enthusiasm to become entrepreneurs (Herdjiono et al., 2017). Motivational theories are widely used in explaining the phenomenon of entrepreneurial decision making (Delmar, 2000; Shane, 2003). Stable motivation is found as a good predictor in the formation of intention to behave (Sheeran, 2003). Motivation as an impetus triggers the growth of behavior influencing decisions on behavior choices, the length of the behavior and the level of effort made can affect the growth of new businesses (Delmar, 2008). Motivation is an impulse that plays a role in the crystallization of intentions on the minds of entrepreneurial subjects before planning the achievement of goals (Ajzen, 1987).

The perceived entrepreneurial motivation of a person refers to their beliefs regarding how interesting the idea of choosing an entrepreneurial career path in a particular country. The level of attractiveness may be related to the economic benefits derived from entrepreneurial activities, and the possibility of achieving independence, achieving certain goals and becoming rich (Solesvik, 2013). Motivation theory provides a good starting point for understanding choices made by entrepreneurs. Furthermore, (Shane, 2003; Eijdenberg et al., 2015) believe that "the development of entrepreneurial theory requires consideration of the motivations of people making entrepreneurial decisions". Individuals with high entrepreneurial motivation are more likely to become entrepreneurs (Shane, 2003). Likewise (Collins, 2004) found that entrepreneurial motivation was significantly and positively related to the choice of entrepreneurial career paths. Based on the description, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis

H1: Perceived Desirability has a positive effect on New Venture Creation Intention

H2: Perceived Desirability has a positive effect on Entrepreneurial Motivation

H3: Entrepreneurial Motivation has a significant effect on New Venture Creation Intention

Research Model

Research Method

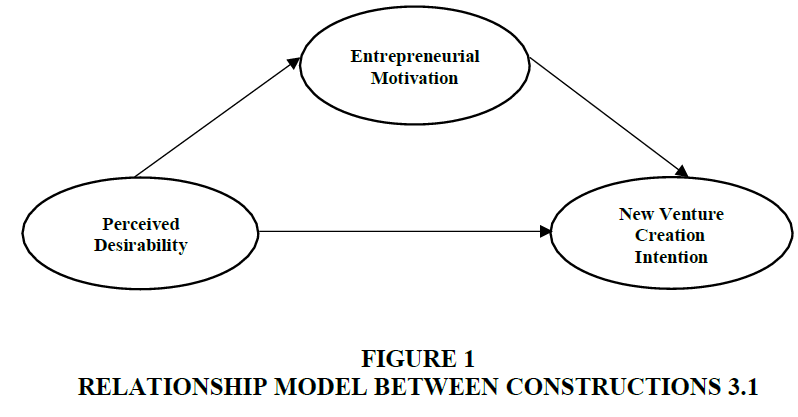

This survey (Figure 1) aims to analyse the effect of mediating entrepreneurial motivation in the relationship of perceived desirability with the intention of creating new businesses. Thus, perceived desirability acts as an independent variable, entrepreneurial motivation as a mediating variable, and the intention to create new businesses as the dependent variable. Data collection was carried out using a questionnaire containing questions about the respondent's profile and research variables, namely perceived desirability, entrepreneurial motivation, and new venture creation intention. Measurement of the research variables is done by using question items developed from concepts, theoretical statements from experts, and the results of previous studies. Overall this question item is measured using 5- Likert point format formats ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree).

This survey randomly gathered 200 visitors in the border region of North Kalimantan with an unlimited population size, and a sample of respondents who had the intention to open a new business. Data collection by sample size is based on a ratio of 1 to 10 for maximum. Therefore, the sample is 7 x 27 = 189 respondents. In anticipation of a questionnaire that could not be entered, the authors distributed 200 respondents. Before filling out the questionnaire, respondents were asked in advance whether they had the intention to open a new business. If "yes", then they are asked to fill it. If "no", they are not asked to fill it out. From the results of the distribution of these questionnaires, there were 4 questionnaires that were not used so that they could not be involved in the next stage of data analysis. Thus, the total survey sample was 196 people.

The data that has been collected, then analyzed using descriptive statistics with SPSS 21 to describe the profile of respondents. After that proceed with using Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling software, SmartPLS-3 is used to analyze the relationship between indicators and constructs (measurement models) and also relationships between constructs (structural models) (Hair, 2014).

Research Findings

The profile of 196 respondents on this study, generally those (56.1%) aged 24-25 years. Likewise, generally they (57, 1%) are women. Viewed from their marital status, they (57.7%) more married than unmarried (40.8%). However, there is a widow / widower status (1, 5%). Of 113 respondents who were married and 3 widows / widowers, generally they (76.9%) had 1- 2 children. Work experience of respondents is quite varied. There is less than 1 year experience and some are more than 25 years. However, the largest percentage (25.9%) is in the 11-15 years work experience category. Most respondents graduated from high school (54.1%) and had the intention to become entrepreneurs. Not only work experience, respondent's work also varies. However, most of them (36.7%) work as private employees. Generally respondents (81.1%) have savings in the Bank and most of them (56.6) have savings in the Bank whose amount is less or equal to Rp. 10,000,000.

Evaluation of the Measurement Model

The measurement model must have a satisfactory level of validity and reliability to test significant relationships in the structural model (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Validity testing is done with convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity assessment is done by looking at the value of external louding (standard loading factor). The construct is said to have good convergent validity if all indicators are statistically significant and also the value of the outer coupling of all indicators is above 0.70 (Hair, 2017). However, at the research development stage the loading scale of 0.50 to 0.60 is still acceptable (Ghozali, 2015). In addition to seeing the value of external loading, an assessment of convergent validity is also done by looking at the value of Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The AVE value of the construct above the outer louding above 0.50 indicates that the construct has convergent validity (Hair, 2011). The outer loading for all factor loading values are above 0.5 and are significant at 0,000. Thus, the construct can be said to have a good convergent validity. Whether or not convergent validity of a construct can also be seen from the value of Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

All factor loading values are above 0.5 and are significant at 0.000. Thus, the construct can be said to have a good convergent validity. It appears that all constructs have good reliability because the loading factor is above 0.5 and significant at 0.000. Likewise, all constructs have good convergent validity because the loading factor is> 0.50 and is significant at p = 0000, and the AVE value for all constructions> 0.50. Whether or not the convergent validity of a construct can also be seen from the value of Average Variance Extracted (AVE). The discriminant validity test with the criteria of Fornell and Larcker (1981). From this table it can be concluded that all constructs have good discriminant validity because the value of AVE square root is higher than the correlation value between constructs.

The value of Composite Reliability> 0.7, which means the construct of Entrepreneurial, Motivation, Entrepreneurial Motivation * Financial Capital, Financial Capital, New Venture Creation Intention, Perceived Desirability has good reliability. Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and composite reliability test results show all indicators and constructs in this study are valid and reliable.

Evaluation of Structural Models

Evaluation of structural models is done by looking at the coefficient of determination (R2), cross-validated redundancy (Q2), path coefficient, and effect size (f2). (Hair et al., 2014), said that before evaluating the inner model based on these criteria, PLS-SEM researchers need to first test whether the model contains an element of multicollinearity.

The results of Collinearity Statistics (VIF) above shows that all indicators have a VIF value of less than 5. This means that the SEM-PLS model is free from multicollinearity problems. "5" as the maximum level of VIF (Ringle, 2015).

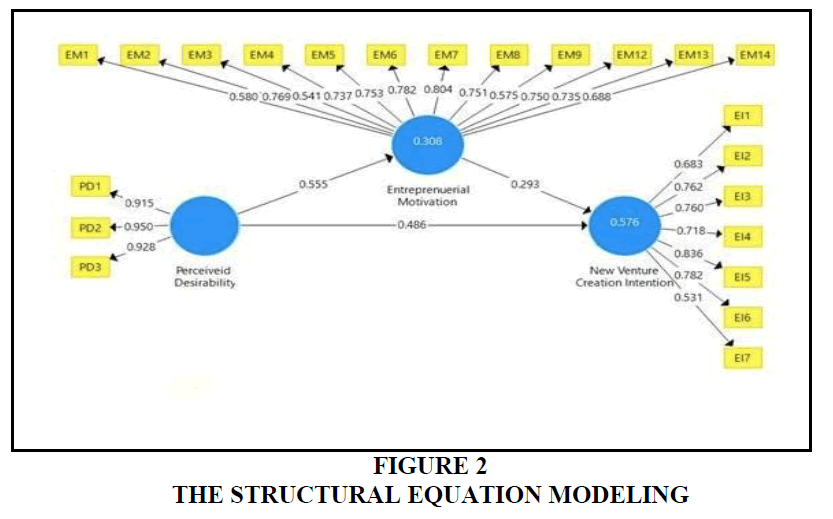

The R-Square Entrepreneurial Motivation value of 0.308 (Figure 2) Source: Primary data processed, (2020)) means the variability of the Entrepreneurial Motivation construct that can be explained by the Perceived Desirability construct of 30.8%, while the R-Square New Venture Intention Value of 0.576 means the construct variability that can be explained by the construct of Perceived Desirability and Entrepreneur Motivation, of 57.6%. According to Chin (1998) in Yamin & Kurniawan (2011) the R-Square criteria consists of three classifications, namely: R2 values 0.67, 0.33 and 0.19 as substantial, moderate (weak) and weak (weak). Thus, the value of R Square is classified as moderate (Table 1).

| Table 1 R Square and R Adjusted | ||

| R Square | R Square Adjusted | |

| Entreprenuerial Motivation | 0,308 | 0,305 |

| New Venture Creation Intention | 0,576 | 0,567 |

The Construct Crossvalidated Redundancy table above shows the Q2 value of the constructs of Entrepreneurial Motivation and New Venture Creation Intention, each of 0.143 and 0.288 which is greater than> 0. This shows that the model has predictive relevance (Table 2).

| Table 2 Blindfolding, Construct Crossvalidated Redundancy | |||

| SSO | SSE | Q2 (=1- SSE/SSO) | |

| Entreprenuerial Motivation | 2.352,000 | 2.015,319 | 0,143 |

| New Venture Creation Intention | 1.372,000 | 9,76,532 | 0,288 |

| Perceived Desirability | 5,88,000 | 5,88,000 | |

The Construct Crossvalidated Redundancy Table 2 above shows the Q2 value of the constructs of Entrepreneurial Motivation and New Venture Creation Intention, each of 0.143 and 0.288 which is greater than> 0. This shows that the model has predictive relevance.

Direct Effect

The results of testing using PLS in the Table 3 prove that the p value for the perceived desirability relationship with Entrepreneurial Motivation amounted to Entrepreneurial Motivation with New Venture Creation Intention and the perceived desirability with New Venture Creation Intention of 0,000 with a positive coefficient proving that all hypotheses were accepted.

| Table 3 Direct Effect | |||||

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | |

| Entreprenuerial Motivation -> New Venture Creation Intention | 0,293 | 0,298 | 0,066 | 4,430 | 0,000 |

| Perceived Desirability -> Entreprenuerial Motivation | 0,555 | 0,561 | 0,048 | 11,592 | 0,000 |

| Perceived Desirability -> New Venture Creation Intention | 0,486 | 0,487 | 0,067 | 7,229 | 0,000 |

Mediation Analyzes

Table 4 below shows that the indirect effect of perceived desirability on new venture creation intention through entrepreneurial motivation is significant and positive (β = 0.163, p> 0.05). This means that entrepreneurial motivation mediates the relationship between perceived desirability and new venture creation intention or entrepreneurial motivation acts as a mediating variable/mediator.

| Table 4 Indirect Effect | |||||

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | |

| Perceived Desirability -> Entreprenuerial Motivation -> New Venture Creation Intention | 0,163 | 0,166 | 0,036 | 4,519 | 0,000 |

From the Path Coefficients table it is known that there is an influence of entrepreneurial motivation on new venture creation intention, there is an influence, perceived desirability on entrepreneurial motivation, and there is a direct effect of perceived desirability on new venture creation intention. Meanwhile, from the Specific Indirect Effects table, it is known that there is an effect of perceived desirability on new venture creation intention through entrepreneurial motivation. Thus, it can be concluded that entrepreneurial motivation partially mediates the relationship between perceived desirability and new venture creation intention.

Discussion

There is the influence of perceived desirability, entrepreneurial motivation on new venture creation intention. From the Path Coefficients table it is known that there is an influence of entrepreneurial motivation on new venture creation intention, there is an influence, perceived desirability on entrepreneurial motivation, and there is a direct effect of perceived desirability on new venture creation intention. While from the Specific Indirect Effects Table 4, it is known that there is an influence of perceived desirability on new venture creation intention through entrepreneurial motivation. Thus, it can be concluded that entrepreneurial motivation partially mediates the relationship between perceived desirability and new venture creation intention.

The results show that there is an effect of perceived desirability on new venture creation intention, this is consistent with research conducted by (Segal et al., 2005, Alhaj 2011; Dissanayake 2013; Zhang 2014; Solesvik et al., 2012; Solesvik et al., 2014; Yatribi 2016; Boukamcha, 2015). There is an influence of entrepreneurial motivation on new venture creation intention. The results of this study are consistent with research conducted by (Solesvik, 2013; Taormina, 2007; Swierczek, 2003).

The findings also written in Table 1 illustrate the research profile of 196 respondents, generally those (56.1%) aged 24-25 years. Likewise, generally they (57, 1%) are women. Viewed from their marital status, they (57.7%) more married than unmarried (40.8%). However, there is a widow / widower status (1, 5%). Of 113 respondents who were married and 3 widows / widowers, generally they (76.9%) had 1- 2 children. Work experience of respondents is quite varied. There is less than 1 year experience and some are more than 25 years. However, the largest percentage (25.9%) is in the 11-15 years work experience category. Most of the respondents graduated from High School (54.1%) and had the intention to become entrepreneurs. Not only work experience, respondent's work also varies. However, most of them (36.7%) work as private employees. Generally respondents (81.1%) have savings in the Bank and most of them (56.6) have savings in the Bank whose amount is less or equal to Rp. 10,000,000.

Conclusion

Perceived desire has a significant influence on the intention to create new businesses, entrepreneurial motivation also has a significant influence on the intention to create new businesses and entrepreneurial motivation also mediates some of the relationship between desirable desirability with intentions to create new businesses, entrepreneurial motivation and intention to create new businesses that show negative results in the above research, The results of the above research provide information that perceived desires have a significant influence on the intention to create new businesses through entrepreneurial motivation in partial mediation. This research still has a greater opportunity to be developed and can still be reexamined this concept elsewhere to study the theory of entrepreneurial intentions more deeply. because the latest results contradict the notion, new research channels can be opened to clarify the reasons for this situation.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research, 129-385.

- Alfonso-Gusman. (2012). Entrepreneurial intention models as applied to Latin America. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 25, 721-735.

- Alhaj, Y.M.Z.E.N. (2011). Entrepreneurial Intention: An Empirical Study of Community College Students in Malaysia. Jurnal Personalia Pelajar.

- Boukamcha. (2015). Impact of training on entrepreneurial intention: an interactive cognitive perspective. European Business Review, 27(6).

- Collins C., Hanges, P., & Locke, E.A. (2004). The relationship of achievement motivation to entrepreneurial behavior: A meta-analysis. Human Performance, 17(1), 95-117.

- Coupez, A., Brognaux, C., & Lejeune, C. (2016). Sharing economy: A drive to success: The case of go-jek in jakarta, indonesia. Research Master’s Thesis, Universite Catholique de Louvain.

- Delmar, F., & Davidsson. (2000). Where do they come from? Prevalence and characteristics of nascent entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship & regional development, 12(1), 1-23.

- Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2008). The effect of small business managers’ growth motivation on firm growth: A longitudinal study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 437-457.

- Dissanayake. (2013). The impact of perceived desirability and perceived feasibility on entrepreneurial intention among Undergraduate Students in Sri Lanka: An Extended Model. The Kelaniya Journal of Management, 2(1), 39-57.

- Edelman, L.F., Brush, C.G., Manolova, T.S., & Greene, P.G. (2010). Start-up motivations and growth intentions of minority nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(2), 174-196.

- Eijdenberg, E.L., Paas, L.J., & Masurel, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial motivation and small business growth in Rwanda. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 7, 212-240.

- Esfandiar Kourosh, L.G., & Mohamad Sharifi Tehrani. (2016). Entrepreneurial Intentions of Tourism Students: An Integrated Structural Model Approach. International Conference.

- Fitzsimmons.( 2011). Interaction between feasibility and desirability in the formation of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing.

- Garba., K.S., Nalado, A.M. (2014). An assessment of students entreprenuerial intentions in tertiary institution : A case of kano state polytechnic, Nigeria. International Journal Of Asian Social Science.

- Garcia-Rodriguez, F.J., Gil-Soto, E., Ruiz-Rosa, I., & Gutierrez-Tano, D. (20170. Entrepreneurial process in peripheral regions: the role of motivation and culture. European Planning Studies, 25(11), 2037-2056.

- Ghozali, I., & Latan, H. (20150. Partial Least Squares: Konsep, Teknik dan Aplikasi Menggunakan SmartPLS 3.0, Semarang, Indonesia, Universitas Diponegoro.

- Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). 2th edn: . SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles.

- Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. The Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice,19(2), 139-52.

- Hair, J.F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V.G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106-21.

- Han, H., & Kim, Y. (2010(. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 29, 659-668.

- He, C., Lu, J., & Qian, H. (2019). Entrepreneurship in China. Small Business Economics, 52, 563-572.

- Herdjiono, I., Puspa, Y.H., Maulany, G., & Aldy, B.E. (2017). The factors affecting entrepreneurship intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Knowledge, 5,5-15.

- Kajiun, S.P.I. (2015). A comparative study of the Indonesia and Chinese educative systems concerning the dominant incentives to entrepreneurial spirit (desire for a new venturing) of business school students. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (2015)4:1.

- Kruger, H., Norris, F., Reilly. M.D., Carsrud Alan, L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 22.

- Ringle, C. M. 2015. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. January 2015Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43(1), 115-135.

- Segal, G., Borgia, D., & Schoenfeld, J. (2005). The motivation to become an entrepreneur. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 11, 42-57.

- Shane, S.L.E.A., & Collins Christopher, J. (2003). Entrepreneurial Motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257-79.

- Shapero, A.S.L. (1982.) Social dimension on entrepreneurship. In Kent, C.A, Sexton, & Vesper, K.H., Eds. Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship.Englewood Cliffs (NJ): Prentice Hall.

- Sheeran, P., & Abraham, C. (2003). Mediator of moderators: Temporal stability of intention and the intention-behavior relation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(2), 205-215.

- Solesvik, (2013). Entrepreneurial motivations and intentions: investigating the role of education major. Education + Training, 55(3), 253-271.

- Solesvik, M., Harry Matlay, P., Westhead, P., & Matlay, H. (2014). Cultural factors and entrepreneurial intention. Education + Training, 56, 680-696.

- Solesvik, M.Z., Matlay, H., Westhead, P., Kolvereid, L., & Matlay, H. (20120. Student intentions to become self-employed: the Ukrainian context. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19, 441-460.

- Swierczek, (2003). Motivation , entreprenuership and the peformance of SMEs in Vietnam. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 11(1) 47-68.

- Taormina, R.J.L.S.K.M. (2007). Measuring chinese entrepreneurial motivation personality and environmental influences. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 13(4), 200-221.

- Yatribi. (2016). Application of krueger’s model in explaining entrepreneurial intentions among employees in Morocco. International Journal of Human Resource Studies.

- Zhang, Y., Duysters, G., & Cloodt, M. (2014). The role of entrepreneurship education as a predictor of university students’ entrepreneurial intention. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 10, 623–641.