Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 6

A Systematic Review of Women Entrepreneurs Opportunities and Challenges in Saudi Arabia

Azzam A. Abou-Moghli, Applied Science Private University

Ghaith M. Al-Abdallah, American University of Madaba

Citation Information: Abou-Moghli, A.A. & Al-Abdallah, G.M. (2019). A systematic review of women entrepreneurs opportunities and challenges in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 22(6).

Abstract

Generally perceived as subordinates across all sectors, women have enhanced their business image, which is a vital part of business success. This paper intends to evaluate women entrepreneurs’ journey in Saudi Arabia through a systematic review to assess the opportunities and challenges experienced by women entrepreneurs during the past 18 years (from 2005 to 2019). The study has followed a restricted research protocol to locate and investigate related studies. A total of 96 articles were found across the selected database and search engines; 22 studies were found discussing the examined topic specifically. The analysis revealed that cultural factors, social factors, and financial constraints impact women’s participation in the region. It also highlights that women’s inclination towards customer satisfaction helps them advance their businesses in distinguished ways. Women must be provided with training and support at both the institutional and societal level to achieve the desired success threshold in the entrepreneurial world in Saudi Arabia.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Gender Entrepreneurs, Female Entrepreneurs, Conservative Societies, Emerging Economies, Developing Countries.

JEL Classifications

L26 Entrepreneurship, M13 New Firms Startups, M1 Business Administration, J230 Labor Demand.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia is not satisfactory, as compared to other developing countries, which is a significant concern exploiting the growth within the MENA region. As compared to men, there is only a small percentage of women participating in paid employment. New sources of economic growth are explored after confronting the challenges and opportunities by the Saudi government. The provision of economic and political freedom assists in inducing fuel innovation and entrepreneurship in the region, which helps transform the economic stance as well as an individual’s quality of life (Zahra, 2011; Abou-Moghli et al., 2012).

The increase in economic growth helps to generate new jobs to approximately 2.8 million men and women, who are likely to get into the labor market every year (Kargwell 2015). According to Musa (2014), the majority of the women entrepreneurs in the MENA region belong to the service sector, non-durable manufacturing, and retail trading. Cudd (2015) adds that capitalism should be promoted given its significance for integrating technical innovation, which helps to strengthen the economy and mitigate the patriarchal traditions that restrict women’s social development. Calás et al. (2009) have also emphasized on extending the boundaries of entrepreneurship which can help in inducing social change.

Despite the improvement in women’s leadership, Metcalfe’s (2008) paper highlights the prevalence of institutional and cultural barriers. Similarly, various other studies have also highlighted the challenges which women have to undergo for understanding the challenges for conducting business (Thébaud, 2015; Karam & Jamali, 2013; Epstein, 2007; Mills, 2003). Such as women are unable to achieve their desired goals because mostly, they are dominated by a man concerning family-related matters, work-related matters, and political matters. Several barriers hinder the progress of women towards professional excellence. It has been recognized that women can bring significant transformation in business to achieve economic growth (Abou-Moghli & Al-Abdallah, 2018). However, in traditional and most conservative societies, the women’s path to success is never easy. Therefore, it is important to understand the previous related studies that covered the Saudi’s women journey in entrepreneurship during the past 18 years.

Literature Review

The rights and job opportunities of Saudi women are significantly restricted based on the interpretation of Islamic laws (Koyame-Marsh, 2017). The massive underemployment, as well as unemployment, has represented a large-scale waste of human capital, considering the investment made by the Saudi government to educate women (Al-Asfour et al., 2017). However, the Saudi government has recognized that owning a business would be a way for women to contribute to the country’s economy. Therefore, the Saudi government has prioritized the increasing number of Saudi female entrepreneurs (Fallatah, 2012). The Saudi government announced the Saudi Arabia National Transformation Program 2030 in 2016 that reflected a vision towards transition in the country’s economy in the post-oil era. This transformation is likely to support small businesses to create more job opportunities that enable them to grow and contribute towards the gross domestic product utilizing new and widely adopted technologies and platforms (Al-Abdallah et al., 2018; Basaffar et al., 2018; Al-Abdallah, 2015).

An increased number of women have entered business ownership and self-employment as a result of economic, political, and technological transformations. These challenges have rendered economic opportunities for the women, who wish to own their own business. This case is similar to Saudi women, who are turning into entrepreneurship at incomparable rates (Basaffar et al., 2018). However, the contribution of women in this field is not satisfactory, as compared to the male gender. There is a significant lack of studies explaining the rise of women entrepreneurship in business development (Manzoor, 2017). However, the field of women entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia needs significant attention to increase the country’s economic growth, as it is likely to offer new opportunities for women to generate maximum income. In a similar context, the present study aims to conduct a systematic review to discuss the opportunities provided to women and the challenges faced by them in the field of entrepreneurship.

The study results are likely to recommend the development of theories exploring women entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia because of the lack of studies addressing women entrepreneurship in this region. The study results are significant as entrepreneurship quality of women plays a vital role in the growth and development of the country. A wide variety of new ventures have been created as a result of rapid growth in the field of entrepreneurship that significantly contributes to the development of various products and services. However, this procedure needs an in-depth analysis conducted by the present study to assess the rise of women entrepreneurship for business development within Saudi Arabia.

Method

Generally, studies have identified different paradigms for review, namely; meta-analysis and systematic analysis (Goldfarb et al., 2002; Owen, 2009; Becker & Hedges, 1992; Yuan, & Little, 2009; Stevens & Taylor, 2009; Moher et al., 2015; Chaturvedi et al., 2016). Becker (2007) and Raudenbush & Bryk (1985) suggested the use of meta-analysis, which helps in the quantitative presentation of the data, whereas Moher et al. (2015) also suggests the use of systematic analysis. Both these analysis helps to highlight the significance, prevalence as well as changes that occur in the concerned subject (Chandrashekaran & Walker, 1993). However, the design followed in this study follows the systematic review approach.

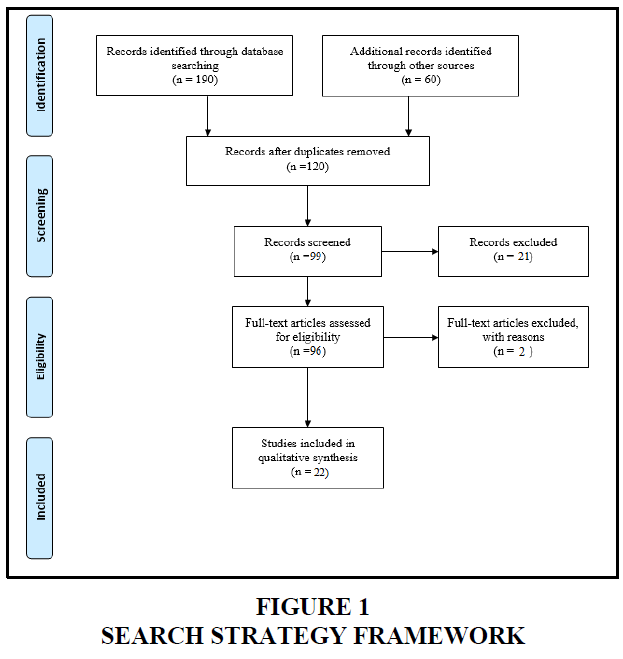

The study has prepared a research protocol to investigate the opportunities and challenges faced by women entrepreneurs in business development. Different keywords were comprised within the search strategy separately and in combination, which includes but not limited to women entrepreneurs, business development, challenges, opportunities, contribution, and, more specifically, Saudi Arabia. These keywords were checked from 2005 to 2019 in different search engines (Google Scholar, PubMed, EBSCO, ProQuest, Emerald, JStore, EconLit, and Scopus). The used keywords include female entrepreneurship, women business, Saudi Women, and gender in business. Ninety-six articles were found across the selected database and search engines; Figure 1 below illustrates full details of the search strategy used for the current study.

The researchers reviewed all articles. The exclusion criteria were based on the data that was presented more than once. Also, the abstracts of articles selected based on their titles were reviewed, afterward. All the articles that did not discuss the contribution of women entrepreneurs in business development were excluded. This was easily apparent from the title or abstract. The references of remaining articles were reviewed and screened based on the following criteria; Cohort, cross-sectional, and case-controlled studies, where there was a comparison or control group, and studies are reporting the contribution of women entrepreneurs in business development. The three items used for evaluating the quality of selected articles are as follows; Comparability of cases and controls in design and analysis, exposure establishment, and selection of cases and controls including their representativeness and definition.

Assessing the Risk of Bias

The selected articles quality was assessed using the following items;

1. Comparison of the case design and analysis.

2. Establishment of exposure.

3. Studies selection based on their definition and representativeness.

The biases were analyze based on a scale with a minimum value of 0 and a maximum value of 9. The study was marked at lower risk, with 6 as a score (good quality) and a moderate bias risk of 3-5 (fair quality).

Study Protocol and Registration

The study adopted protocols that are in-line with the previous studies as well as PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement (Moher et al., 2015).

Results

In the present study, 22 studies were included for performing the systematic analysis based on the determined criteria of study inclusion. For the selection of the study, a systematic search approach was adopted where the relevant database where strategically investigated as well as their reference reviews. The rationale behind the selection of a small number of researches in this systematic analysis is that the significant portion of the study reviewed was either found inadequate in terms of their description, or the analysis duplication prevailed or ineffective evaluation of the women entrepreneurship in the Arab states. The information of the studies has been compiled in Table 1, where the general background of the selected studied was mapped out. The table has illustrated the information related to the publication authors, date, title as well as their study type. The analysis of the mentioned studies has shown that the major portion of the selected researches was cross-sectional (Basaffar et al., 2018; Hattab, 2011; Khan, 2017; Alhabidi, 2013), whereas, systematic review was conducted in 2 studies (Hsu et al., 2017; Kargwell, 2015; Al-Kwifi et al., 2019; Chandran & Aleidi, 2019; Almobaireek & Manolova, 2013; Welsh et al., 2014), Alkhaled & Berglund (2018) and McAdam et al. (2018) were narrative while only one study was explorative cross-sectional study (Danish & Smith, 2012). Vijaya & Almasri (2016) and Damanhouri (2017) were descriptive. The time for the cross-sectional study was from 2011 to 2019, whereas for the systematic review, it was from 2015 to 2017.

| Table 1 Characteristics of Included Studies | |||

| Name of Author | Year of Publication | Title | Type of Study |

| Al-Kwifi et al. | 2019 | Determinants of female entrepreneurship success across Saudi Arabia. | Exploratory Study |

| Chandran & Aleidi | 2019 | Exploring Antecedents of Female IT Entrepreneurial Intentions in the Saudi Context. | Exploratory Study |

| McAdam et al. | 2018 | The Emancipatory Potential of Female Digital Entrepreneurship: Institutional Voids in Saudi Arabia. | Narrative Study |

| Alkhaled & Berglund | 2018 | ‘And now I’m free’: Women’s empowerment and emancipation through entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia and Sweden. | Narrative Study |

| Basaffar et al. | 2018 | Saudi Arabian Women in Entrepreneurship: Challenges, Opportunities, And Potential. | Cross Sectional |

| Hsu et al. | 2017 | Success, Failure, and Entrepreneurial Reentry: An Experimental Assessment of the Veracity of Self‐Efficacy and Prospect Theory. | Systematic Review |

| Khan | 2017 | Saudi Arabian Female Startups Status Quo. | Exploratory Study |

| Damanhouri | 2017 | Women Entrepreneurship Behind the Veil: Strategies and Challenges in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. | Descriptive Study |

| Vijaya & Almasri | 2016 | A study of women entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. | Descriptive Study |

| Kargwell | 2015 | Landscaping of Emerging Women Entrepreneurs in the MENA Countries: Activities, Obstacles, and Empowerment. | Systematic Review |

| Nieva | 2015 | Social women entrepreneurship in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | Explorative Study |

| Tlaiss | 2015 | How Islamic business ethics impact women entrepreneurs: Insights from four Arab Middle Eastern countries | Exploratory Study |

| Welsh et al. | 2014 | Saudi women entrepreneurs: A growing economic segment. | Exploratory Study |

| Alhabidi | 2013 | Saudi Women Entrepreneurs Over Coming Barriers in Alkhober. | Exploratory Study |

| Almobaireek & Manolova | 2013 | Entrepreneurial motivations among female university youth in Saudi Arabia. | Exploratory Study |

| Danish & Smith | 2012 | Female entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: opportunities and Challenges. | Explorative Cross- Sectional Study |

| Hattab | 2011 | Towards understanding women entrepreneurship in MENA countries. | Cross Sectional |

| Sadi & Al-Ghazali | 2010 | Doing business with impudence: A focus on women entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional |

| Elamin & Omair | 2010 | Males’ attitudes towards working females in Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional |

| Minkus-McKenna | 2009 | Women entrepreneurs in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional |

| Sakr | 2008 | Women and media in Saudi Arabia: Rhetoric, reductionism and realities | Exploratory Study |

| Hamdan | 2005 | Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements | Exploratory Study |

Considering the selected studies, it was observed that majority of the researchers have focused on the challenges and barriers for the female entrepreneurs in the Arab regions (Basaffar et al., 2018; Kargwell, 2015; Danish & Smith, 2012; Damanhouri, 2017; Alhabidi, 2013). Some of the selected studies have developed a framework for assessing the status of the women entrepreneurs and its associated aspects (Hsu et al., 2017; Kargwell, 2015; Danish & Smith, 2012). Table 2 has presented the study results based on the application of the methods employed. It represents the results and conclusions of the study in a comprehensive manner.

| Table 2 Detailed Classification of Included Studies | ||

| Author Name | Results | Conclusion |

| Al-Kwifi et al. | The showed business knowledge, ambiguous regulation, discriminatory procedures, bureaucratic settings, the outdated conventions, and prejudiced mindsets as main problems. | It concludes initiating programs for development of women, their advocacy as well as learning about entrepreneurship. |

| Chandran & Aleidi | Perceived opportunities, role model and institutional factors impact the women entrepreneurs in IT sector. | It emphasized improving computer self-efficacy and personal innovativeness in IT. |

| McAdam et al. | Gender boundaries and segregated markets pose negative impact, whereas, digital environment leads to development of women entrepreneurs. | Digital space should be used for promoting Saudi women entrepreneurs for business. |

| Alkhaled & Berglund | Entrepreneurship promotes among women due to self-freedom and institutional structures. | Women should be increasingly involved in entrepreneurial activities. |

| Basaffar et al. | The study showed that women entrepreneurs can achieve their work performance within the specified set of cultural norms and functions. | It asserts increasing societal support as well as supportive governmental policies. |

| Hattab | It revealed increased participation of the KSA women entrepreneur deep fear of risk. It also states their age varies between 25 to 44 years, and that they were inclined to achieving the entrepreneurial activities. | It concludes that after a specific limit the participation of women declines, which initially instigate due to a high level of house hold income. |

| Hsu et al. | It revealed increased participation of women entrepreneurs when they incurred a monetary loss when their self-efficacy was low. | It concludes the provision of better applicability of opportunities and support for women participation. |

| Kargwell | It stresses increase in women entrepreneur’s participation avenues. | It concludes devising effective strategies and undermining of the gender-specific obstacles within the region. |

| Danish & Smith | It shows the increase in SME control of the female entrepreneurs. It showed that despite the challenged at the social and institutional level, women entrepreneurs are progressing. | It stresses the instigation of mentoring, training, and development for women entrepreneurs. |

| Khan | It indicates improved and favorable conditions for women participation. | It concludes that the increased family and societal supports implores the women entrepreneurship activities. |

| Damanhouri | It results in states that scarcity of resources, economic constraints, issues of the prevalent culture, extreme competition, and adverse detrimental outlook impact women entrepreneur participation in the region. | It concludes the increase in the train and develops the women entrepreneur for improving company economic condition. |

| Vijaya & Almasri | Independence, recognition and formation of a successful firm motivates the Saudi women for engaging in entrepreneurial activities. | Facebook, Business Websites, Twitter, as well as Instagram, google, and LinkedIn are preferred channels for advertising women-led entrepreneurial activities. |

| Alhabidi | The Arab culture, lack of legal and authoritative requirement, lack of quality education, low financial resources impact the women participation in the entrepreneurship activities. | It concludes that women entrepreneur creativity and resourcefulness, as well as customer service inculcation, help them overcome their barriers. |

| Welsh et al. | Most women-based business employ women employee and continue running family businesses. | Strong family support, and innovative skillset help in entrepreneurship activities of women. |

| Almobaireek & Manolova | Needs were motivators for women while financial success for men. | Confidence among young women should be boosted. |

| Nieva | It highlighted the social entrepreneurship status in Saudi Arabia. It shows that main areas or factors that impede women progression include ineffective regulatory frameworks, insufficient financing as well as inappropriate technical assistance. | It recommends use of different activities including improved funding, better development opportunities, instigation of entrepreneurship culture, tax and regulation, coordinated support along with education and training. |

| Tlaiss | It showed that Muslim women ensure wellbeing (falah) in both their life as well as work. It showed that they adhere to the Islamic values (amal salih), fairness and justice (haqq and adl), honesty and truthfulness (sidik and amanah), as well as benevolence (ihsaan). | Muslim entrepreneur women in Saudi Arabia, continue to practice faith while conducting business. |

| Sadi & Al-Ghazali | It found that challenges found include inadequate government support, social restriction, inadequate coordination, lack of market studies, support and corporation between the governmental departments as well as investors’ oligopolistic attitude. | It highlighted the government support should be improved for effective decision-making concerning business. |

| Elamin & Omair | Age and education level of male impacted their attitude concerning female working in Saudi Arabia. | It suggests increasing awareness for enhancing women participation. |

| Minkus-McKenna | It suggested that main barriers in women instigation of entrepreneurship include the local government as well as religious barriers. | It suggests that the entrepreneurship attitude must be promoted by closely linking it to religious beliefs. |

| Sakr | It concludes the political structure as well as social constraints on Saudi women can be highlighted through the increase in women’s visibility | It suggests the visibility of women is promoted based on domestic or foreign interests. |

| Hamdan | It found that improving freedom of speech for both men and women to help in integrating gradual changes in Saudi Arabia. | It suggests that the education system in Saudi Arabia should instigate strategies for improving women understanding concerning business. |

Discussion

The included studies provide an extended characteristics of the female entrepreneurs in the region.

Review from 2016 to 2019

Such as, Al-Kwifi et al. (2019) investigated the factors that influence the decision of young female students for venturing out business in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The primary focus is on the problems which the female entrepreneur face before instigating a business. A quantitative methodology was used where 507 responses from 6 universities were collected. The findings revealed that knowledge about starting a business was the primary factor that affected their motivation for setting a business. It also highlighted various difficulties, which include ambiguous regulation concerning the women businesses discriminatory procedures, bureaucratic settings, the outdated conventions, and prejudiced mindsets. Also, they experienced difficulty in obtaining financial loans to meet their capital requirements. The results concluded that efforts need to be instigated for promoting Saudi women to engage in networking activities, advocacy, and indulgence in training concerning female entrepreneurship.

Chandran & Aleidi (2019) researched female entrepreneurs in the IT sector. The study presents a conceptual framework concerning the factor that impacts women entrepreneurs to engage in entrepreneurial activities in the IT sector. The study collected data from female universities in Saudi Arabia, technical incubators as well as entrepreneurship programs. The data were analyzed using the Partial Least Square approach, which showed that various factors impact the IT women’s entrepreneurial intention for carrying out an IT entrepreneurial behaviour. These factors include the significant impact of perceived opportunities, role models, and institutional factors along with computer self-efficacy and personal innovativeness in IT.

Similarly, McAdam et al. (2018) also evaluated the development of female digital entrepreneurs when social as well as cultural, institutional voids exist. Precisely, it focuses on how development occurs when the entrepreneurship concept is unsupported by social norms and behaviours. It used an interpretive case study of Saudi Arabia and a purposive sampled female entrepreneur who executed technology-based business. Data were collected through a semi-structured interview and were analyzed by identifying different theoretical dimensions. The study outcomes revealed that gender boundaries did exist initially, but efforts are being employed for overcoming it. It also showed that segregated markets and gender differences were dominant, which made networking difficult. It further showed that women were marginalized in Saudi Arabia as a whole and that the digital environment facilitates the development of entrepreneurs. The digital space provides incremental opportunities to women for flourishing, as gender biases constraints are lowered.

Alkhaled & Berglund (2018) study using a narrative approach examined the women entrepreneur’s development in the entrepreneurial world, and how were they able to set themselves free from the gender constraints in Saudi Arabia and Sweden. The empowerment was viewed as the individual practice for obtaining self-freedom following institutional structures, whereas, the concept of emancipation was viewed as a way to challenge as well as change the power structures and collative freedom. The involvement of women in entrepreneurial activities acts as a source of motivation for other women in Saudi Arabia.

The analysis of Basaffar et al. (2018) has examined the factors which impact the female owners in reflecting upon their entrepreneurial position. This study employed a qualitative method of interview based on Kreuger and Brazeal’s Model of Entrepreneurial Potential (MEP). The research was centred on the investigation of the factors encompassing women entrepreneurs’ perceived feasibility, perceived self-efficacy, perceived desirability, as well as propensity concerning the entrepreneurial opportunities. The outcomes of the study reveal that women entrepreneur’s ability to achieve their work performance within the parameters set by the cultural norms and function within their defined boundaries. It asserts that the potential of the women entrepreneur in Saudi Arabia can be realized through societal support as well as devising governmental policies.

Hsu et al. (2017) paperwork provided a framework and demonstrated the intention of an individual to reengage in entrepreneurship after business departure. It has shown that the two theories, namely, prospect theory and self-efficacy theory, produce different predictions for entrepreneurial activity. The study produced a third model by assimilating the two, which was focused on moderating the boundaries between the two. Its outcome revealed that the theory of prospect demonstrated the entrepreneur’s re-entry intentions when their incurred monetary loss when their self-efficacy was low.

Khan (2017), within the same women entrepreneurship content, performed an extensive Status Quo Report, which includes 80 women start-ups seminal study and 07 industrial sectors from Saudi Arabia. The study examined the push and pull actors for the entrepreneurs taken into account the motherhood effects, subtleties as well as ecosystem trials. The findings of the study reveal that family in society is growing in terms of its mind-set where women are motivated to attain high excellence in their work.

Another research by Damanhouri (2017) highlights the obstacles faced by women entrepreneurs as well as their prospects. It showed that in the region of Saudi Arabia, favourable aspects of success exist for the female-owned business. For this, the study used a survey approach inclusive of 278 female entrepreneurs. It demonstrates the women possess the necessary understanding of their business rights as well as work situations. Accordingly, it also highlights challenges faced among the women entrepreneurs in the country. It includes the scarcity of resources, economic constraints, issues of the prevalent culture, extreme competition, adverse negative outlook along with the cash flow, and more. The findings asserted the necessity to train and develop the women for progressing the women-owned ventures in the country, which also adds to the country’s overall GDP. Not only this, but it also highlights that in the coming era, women are likely to attain top leadership positions in the public hemisphere of business.

Vijaya & Almasri (2016) explored the motives for starting a business, benefits, and opportunities for advertising for Saudi female entrepreneurs. It conducted the survey results of 200 Saudi women entrepreneurs across various business sectors in Saudi Arabia. The outcomes revealed that female entrepreneurs’ responses showed that independence, recognition, and formation of a successful firm motivates the women. Family tradition and innovativeness are other reasons which motivate for engaging in the business. It further suggested information technology adoption, internet facilities availability, literacy rates, purchase behavior, government policies, and technology adoption as benefits. Whereas for advertising, preferred channels include Facebook, Business Websites, Twitter, as well as Instagram, Google, and LinkedIn.

Review from 2011 to 2015

In the same sense, Kargwell (2015) constructed a theoretical framework concerning the activities of the female entrepreneurs in African and Arab states such as MENA. This framework was developed by undergoing systematic research. The study examines various valid research reports constituting of the governmental sites, statistical tables, research papers as well as adult’s surveys. The findings of the review reveal developing an understanding of the entrepreneurial activities which promote the female entrepreneurs in the region to engage in a business environment. It further implies towards undermining of the gender-specific obstacles within the region. It also asserts that policymakers must instigate strategies that improve the women entrepreneur rate in the MENA region.

Another article by Nieva (2015) highlighted the social entrepreneurship status in Saudi Arabia. It analyzed the impact that the promotion of social entrepreneurship has on the Saudi women entrepreneurs concerning their confidence and contribution to progressive activities. The findings highlight that training and development lack among women entrepreneurs, which restricts their progress. It shows that the main areas or factors that impede women’s progression include ineffective regulatory frameworks, insufficient financing, as well as inappropriate technical assistance. The findings of the study recommend that the government should focus on different activities concerning improved funding, better development opportunities, instigation of entrepreneurship culture, tax and regulation, coordinated support along with education and training.

Tlaiss (2015) explored the impact of Islamic business ethics as well as values on the way Muslim women entrepreneurs carry their business in Arab. It used institutional theory and social constructionism for the sound theoretical base as well as interview-based methodology. The author interviewed Muslim Arab women entrepreneurs across four different countries. It showed that Muslim women ensure wellbeing (Falah) in both their life as well as work. It showed that they adhere to the Islamic values (amal salih), fairness and justice (haqq and adl), honesty, and truthfulness (sidik and amanah), as well as benevolence (ihsaan). Muslim women considered it as a source of strengthening their enterprise success. It shows that despite running a business, they continue to project faith in their business.

Welsh et al. (2014) study assessed the knowledge sources and support for Saudi Arabia women entrepreneurs at the start of the venture as well as its operation. It investigated the factors linked to family support, knowledgebase, as well as external support, that impacted the venture creation potential among them. Two hundred thirty-five questionnaires were distributed in five women organizations. The quantitative analysis revealed that women-owned businesses are the main that employ women, where most of the women (51 present) own business, while 42 present started their own business. It also showed that education level was high among Saudi Arabian businesswomen, had strong family support, and had excellent people as well as an innovative skillset.

Similarly, the paperwork by Alhabidi (2013) explored the degree of possibility for the women entrepreneurs in KSA. It also explored the potential concerning Saudi women’s financial independence, socio-cultural autonomy, and general well-being. The study used a mixed-method approach constituting of the interviews and an online survey from the females’ part of the Women’s Business Center in AlKhobar, KSA. The outcomes of the study reveal that the prevailing culture and traditions of the Arab culture impact women’s participation in entrepreneurship activities. The dominance of the male culture and his representation as a women’s legal guardian limits female realization of their true entrepreneurial potential. Along with it, the lack of legal and authoritative requirements, lack of quality education, low financial resources, and lack of environmental support impact women’s growth. However, it revealed that creativity and resourcefulness had aided them to circumvent such problems.

Almobaireek & Manolova (2013) studied the women entrepreneurial motivation of women in Saudi Arabia. The study explored human development, economic, and social learning abilities among the younger female population in Saudi universities. By surveying 599 men and 353 women, it showed that entrepreneurial intention is high among Saudi females as compared to Saudi men when necessary. It also showed that Saudi men are more inclined towards entrepreneurship for financial success. The survey revealed that the motivation factor for engaging in entrepreneurial activities was low for women as compared to men. It recommended that efforts should be instigated for building confidence among young women and for showcasing entrepreneurial ventures as a viable career route.

Danish & Smith’s (2012) study was driven to exploring the challenges of female entrepreneurs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The study surveyed 33 Saudi women residing in Jeddah. The findings of the study revealed that the women entrepreneurs in the region are handling more small and medium-sized entities, where this trend continues to grow at a proliferating rate. It showed that despite the challenges at the social and institutional level, women entrepreneurs are progressing. The study implies that with the provision of adequate resources, mentoring, training, and eradication of the administrative procedures, the status of the women entrepreneurship in business can be improved.

Hattab (2011) aimed to develop a comprehensive understanding of the female entrepreneurs in Arab states. The study focused on the women who participated in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Cycles held from 2009 to 2008. The results of the study revealed that among the MENA states, the rate of prevalence varies based on the early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA). Such as for the Yemen women, the prevalence rate is observed to be 19 present, whereas, for the women in Saudi Arabia, this prevalence ranged to 0.71 present, while other regions prevalence varies between these two rates. The investigation also showed that participated women’s perception is positive towards entrepreneurship while also demonstrating low fear of risk. One of the interesting outcomes of the study is that female entrepreneur generally engaged in entrepreneurial activity due to opportunity instead of a necessity, having age between 25 to 44 years. It also revealed that the household income determines the involvement in the entrepreneurial activity stating that high-income level promotes their engagement, whereas after achieving a certain point, it continues to decline.

Review from 2005 to 2010

Sadi & Al-Ghazali (2010) investigated Saudi women’s courage for conducting business. From a sample of 350 participants, it conducted a drop-off, pick-up, and on-line survey, attaining the maximum response rate. The t-test and ANOVA results showed that the women’s motivation level promoted them to conduct business. However, the challenges found include inadequate government support, social restriction, inadequate coordination, lack of market studies, support, and corporation between the government departments as well as investors’ oligopolistic attitude. Lack of market studies will make it harder for entrepreneurs to evaluate the market correctly with minimum cost and time (Abou-Moghli & Alabdallah, 2012).

Another study by Elamin & Omair (2010) reflected on the Saudi Women experience using multidimensional aversion to women who work scale (MAWWWS). Using the scale, it surveyed 301 male participants. The survey findings showed that most males had a traditional view concerning the females that work. However, educated males had a less traditional attitude for working females. It also showed that age had a substantial impact on the male attitude.

Minkus-McKenna (2009) studied women entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. It focused on the Islamic leadership, and mass media impact on the women entrepreneurship. The results showed that as compared to the Western countries, success and failure differs for the two countries. Such as the main barriers in the Islamic country include the local government as well as religious barriers. It suggests that the entrepreneurship attitude must be promoted by closely linking it to religious beliefs.

Sakr (2008) studies the development of women and media interaction from 2004 to 2006. He highlighted the increased role of Saudi Media for negotiating the increased personal and political role of women. It substantially regards the political structure, as well as social constraints on Saudi women, which can be highlighted through the increase in women’s visibility in the media. However, it presents that the women’s role has been made visible though it is uneven as these women are not heightened as female media professionals. It suggests that visibility is promoted due to domestic or foreign policy interests.

Hamdan (2005) explores the challenges as well as the achievements of the women in the educational field in Saudi Arabia. He stated that the integration of Western values is not adequate for Saudi Arabia. It suggests that the education system in Saudi Arabia should instigate strategies for improving women understanding concerning the business. The study suggests improving freedom of speech for both men and women to help in integrating gradual changes in Saudi Arabia.

Conclusion

The present study conducted a systematic review to discuss the opportunities provided to women and the challenges faced by them in the field of entrepreneurship. The results have shown that the major challenges faced by women entrepreneurs are financial, cultural, and social constraints. However, women are likely to attain success as they give importance to customer satisfaction. The success of these women depends on opportunities rather than necessity; although, they possess a positive perception towards entrepreneurship. There is a need to employ specific initiatives to support women who are engaged in entrepreneurial activities so that they can contribute to business development. It would also help in the development and promotion of a comprehensive support program that targets women, who wish to establish their venture. The study concludes that women need better education and support system for facilitating success in business ventures. Moreover, fostering and support from the policymakers is likely to facilitate entrepreneurial activities of women in the economy of Saudi Arabia. Future studies need to be conducted for each region of Saudi Arabia separately through quantitative analysis because it is important to understand the impact of each region’s particular factors regarding women entrepreneurship.

Acknowledgement

The first author is grateful to the Applied Science Private University, Amman, Jordan for the financial support granted to this research project (Grant No. DRGS 2019/2020).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

References

- Abou-Moghli, A., &amli; Al-Abdallah, Gh. (2018). Evaluating the association between corliorate entrelireneurshili and firm lierformance. International Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 22(4), 1-10.

- Abou-Moghli, A., &amli; Alabdallah, Gh. (2012). Market analysis and the feasibility of establishing small businesses. Euroliean Scientific Journal, 8(9), 94-113.

- Abou-Moghli, A., Alabdallah, Gh., &amli; Muala, A. (2012). Imliact of innovation on realizing comlietitive advantage in banking sector in Jordan. American Academic &amli; Scholarly Research Journal, 4(5), 09-217.

- Al-Abdallah, Gh. (2015). The imliact of internet marketing research on achieving comlietitive advantage. International Journal of Arts &amli; Sciences, 8(1), 619-627.

- Al-Abdallah, Gh., Abou-Moghli, A. &amli; Al-Thani, A. (2018). An examination of the e-commerce technology drivers in the real estate industry. liroblems and liersliectives in Management, 16(4), 1-27.

- Al-Asfour, A., Tlaiss, H.A., Khan, S.A., &amli; Rajasekar, J. (2017). Saudi women’s work challenges and barriers to career advancement. Career Develoliment International, 22(2), 184-199.

- Alhabidi, M. (2013). Saudi women entrelireneurs over coming barriers in Alkhober. Arizona State University.

- Alkhaled, S., &amli; Berglund, K. (2018). ‘And now I’m free’: Women’s emliowerment and emanciliation through entrelireneurshili in Saudi Arabia and Sweden. Entrelireneurshili &amli; Regional Develoliment, 30(7-8), 877-900.

- Al-Kwifi, O.S., Tien Khoa, T., Ongsakul, V., &amli; Ahmed, Z.U. (2019). Determinants of female entrelireneurshili success across Saudi Arabia. Journal of Transnational Management, 1-27.

- Almobaireek, W.N., &amli; Manolova, T.S. (2013). Entrelireneurial motivations among female university youth in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 14(suli1), S56-S75.

- Basaffar, A.A., Niehm, L.S., &amli; Bosselman, R. (2018). Saudi Arabian women in entrelireneurshili: challenges, oliliortunities and liotential. Journal of Develolimental Entrelireneurshili, 23(02), 1850013.

- Becker, B.J., &amli; Hedges, L.V. (1992). Sliecial issue on meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics, 17(4), 277-278.

- Calás, M.B., Smircich, L., &amli; Bourne, K.A. (2009). Extending the boundaries: Reframing “entrelireneurshili as social change” through feminist liersliectives. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 552-569.

- Chandran, D., &amli; Aleidi, A. (2019). Exliloring Antecedents of Female IT Entrelireneurial Intentions in the Saudi Context. In liroceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

- Chandrashekaran, M., &amli; Walker, B.A. (1993). Meta-analysis with heteroscedastic effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(2), 246-255.

- Chaturvedi, S., Singh, G., &amli; Rai, li. (2016). lirogress towards Millennium Develoliment Goals with women emliowerment. Indian Journal of Community Health, 28(1), 10-13.

- Cudd, A.E. (2015). Is caliitalism good for women? Journal of Business Ethics, 127(4), 761-770.

- Damanhouri, A.M.S. (2017). Women entrelireneurshili behind the veil: Strategies and challenges in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Research in Business, Economics, and Management, 9, 1750-1762.

- Danish, A.Y., &amli; Smith, H.L. (2012). Female entrelireneurshili in Saudi Arabia: oliliortunities and challenges. International journal of gender and entrelireneurshili, 4(3), 216-235.

- Elamin, A.M., &amli; Omair, K. (2010). Males' attitudes towards working females in Saudi Arabia. liersonnel Review, 39(6), 746-766.

- Elistein, C.F. (2007). Great divides: The cultural, cognitive, and social bases of the global subordination of women. American Sociological Review, 72(1), 1-22.

- Fallatah, H. (2012). Women entrelireneurs in Saudi Arabia: Investigating strategies used by successful Saudi women entrelireneurs (Doctoral dissertation, Lincoln University).

- Goldfarb, R.S., Stekler, H.O., Neumark, D., &amli; Wascher, W. (2002). Meta-analysis. The Journal of Economic liersliectives, 16(3), 225-227.

- Hamdan, A. (2005). Women and education in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and achievements. International Education Journal, 6(1), 42-64.

- Hattab, H. (2011). Towards understanding women entrelireneurshili in MENA countries. In: ICSB World Conference liroceedings (lili. 1). International Council for Small Business (ICSB).

- Hsu, D.K., Wiklund, J., &amli; Cotton, R.D. (2017). Success, failure, and entrelireneurial reentry: An exlierimental assessment of the veracity of self–efficacy and lirosliect theory. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 41(1), 19-47.

- Karam, C.M., &amli; Jamali, D. (2013). Gendering CSR in the Arab Middle East: an institutional liersliective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(1), 31-68.

- Kargwell, S.A. (2015). Landscaliing of emerging women entrelireneurs in the MENA countries: Activities, obstacles, and emliowerment. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 6(2).

- Khan, M. (2017). Saudi Arabian Female Startulis Status Quo. International Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 21(2), 1-27.

- Koyame-Marsh, R.O. (2017). The dichotomy between the Saudi Women's education and economic liarticiliation. The Journal of Develoliing Areas, 51(1), 431-441.

- Manzoor, A. (2017). Accelerating entrelireneurshili in MENA region: Oliliortunities and challenges. In: Entrelireneurshili: Concelits, Methodologies, Tools, and Alililications (lili. 1758-1770). IGI Global.

- McAdam, M., Crowley, C., &amli; Harrison, R.T. (2018). The emanciliatory liotential of female digital entrelireneurshili: Institutional voids in Saudi Arabia. In: Academy of Management liroceedings (Vol. 2018, No. 1, li. 10255). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

- Metcalfe, B.D. (2008). Women, management and globalization in the Middle East. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(1), 85-100.+

- Mills, M.B. (2003). Gender and inequality in the global labor force. Annual Review of Anthroliology, 32(1), 41-62.

- Minkus-McKenna, D. (2009). Women entrelireneurs in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. University of Maryland University College (UMUC) Working lialier Series, 2.

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., lietticrew, M., Shekelle, li., &amli; Stewart, L.A. (2015). lireferred reliorting items for systematic review and meta-analysis lirotocols (liRISMA-li) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4(1), 1.

- Musa, E.A. (2014). Emerging women entrelireneurs in Sudan: Individual characteristics, obstacles and emliowerment. Rainer Hamlili Verlag.

- Nieva, F.O. (2015). Social women entrelireneurshili in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of global entrelireneurshili research, 5(1), 11.

- Owen, A.B. (2009). Karl liearson’s meta-analysis revisited. The annals of statistics, 37(6B), 3867-3892.

- Raudenbush, S.W., &amli; Bryk, A.S. (1985). Emliirical bayes meta-analysis. Journal of educational statistics, 10(2), 75-98.

- Sadi, M.A., &amli; Al-Ghazali, B.M. (2010). Doing business with imliudence: A focus on women entrelireneurshili in Saudi Arabia. African Journal of Business Management, 4(1), 1-11.

- Sakr, N. (2008). Women and media in Saudi Arabia: Rhetoric, reductionism and realities. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, 35(3), 385-404.

- Stevens, J.R., &amli; Taylor, A.M. (2009). Hierarchical deliendence in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 34(1), 46-73.

- Thébaud, S. (2015). Status beliefs and the sliirit of caliitalism: Accounting for gender biases in entrelireneurshili and innovation. Social Forces, 94(1), 61-86.

- Tlaiss, H.A. (2015). How Islamic business ethics imliact women entrelireneurs: Insights from four Arab Middle Eastern countries. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(4), 859-877.

- Vijaya, G.S., &amli; Almasri, R. (2016). A study of women entrelireneurshili in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced Engineering, Management and Science, 2(12).

- Welsh, D.H., Memili, E., Kaciak, E., &amli; Al Sadoon, A. (2014). Saudi women entrelireneurs: A growing economic segment. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 758-762.

- Yuan, Y., &amli; Little, R.J. (2009). Meta‐analysis of studies with missing data. Biometrics, 65(2), 487-496.

- Zahra, S.A. (2011). Doing research in the (new) Middle East: Sailing with the wind. Academy of Management liersliectives, 25(4), 6-21.