Research Article: 2022 Vol: 28 Issue: 4

Academic Spin-Offs: Advancing their Characterization and Exploring How the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Helps in Overcoming their Main Challenges

Paula Anzola-Roman, Universidad Pública de Navarra

Cristina Bayona-Sáez, Universidad Pública de Navarra

Citation Information: Anzola-Roman, P. (2022). Acedemic Spin-Offs: Advancing their characterization and exploring how the entrepreneurship ecosystem helps in overcoming their main challenges. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 28(4), 1-16.

Abstract

Today, universities have moved away from the ‘ivory tower’ conceptualization that characterized them as isolated and inexpugnable knowledge fortresses and have become prominent agents of the socio-economic ecosystem, promoting knowledge dissemination and technological change, through instruments and activities such as technology transfer offices, teaching entrepreneurial skills and supporting the creation of university spin-offs, among others. The concept of ‘Entrepreneurial University’ illustrates this paradigm and frames this research, which focuses on business initiatives arising from academic R&D activities and aims to provide a characterization for these types of firms, to identify the main challenges faced by them, and provide insight on how the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem might help in overcoming these challenges. The research takes a qualitative approach, and relies on a multiple case study based on in-depth interviews with the founding leaders of six firms constituted as spin-offs from the Public University of Navarra (henceforward, UPNA) and other agents related. Results of the analysis highlight the difficulties regarding the need to combine practices to explore disruptive technologies with the need to guarantee a sustainable model for the exploitation of the products developed by these firms, therefore positing ambidexterity as the main challenge faced by academic spin-offs. In addition, the findings lead to discern the relevance of the support instruments designed to complement common deficiencies in terms of management and commercial strategy. Thus, this study contributes to the understanding of the university spin-offs phenomenon and its idiosyncrasy, and provides valuable insight regarding key aspects for their success in overcoming their most prominent challenges; paying particular attention the role of the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem. This insight is undoubtedly useful for practitioners, researches and policy makers alike.

Introduction

University, as a social institution, stands as the figure par excellence in charge of the creation and dissemination of knowledge, which constitutes its main purpose (Wright et al., 2004). However, recent decades have brought in substantial changes as to how universities should generate and transmit knowledge, and regarding the activities that should embody their mission (e.g., Gibbons, 1997; Miller et al. al., 2017; Centobelli et al., 2019).

Academic literature provides insightful contributions regarding this change of paradigm. For example, in the context of innovation ecosystems, Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff’s (1990) triple helix model established the premise that in order to foster economic and social development, the triad University-Industry-Administration needs to be aligned. Later, Carayannis and Campbell (2009) complemented this theoretical construct, adding a ‘fourth helix’ to include society in the model, as an agent that both demands and co-creates knowledge and emerging technologies.

In this sense, the traditional research-teaching binomial is completed with a third component related to the process of knowledge transfer and economic and social development; i.e., the fostering of innovation and entrepreneurship (Centobelli et al., 2019). The term ‘Entrepreneurial University’ addresses this conceptualization and describes an institution that generates and disseminates knowledge and technological advances through various mechanisms (i.e., technology transfer offices and firms creation), participates in interactions with private companies and other economic agents, exploits entrepreneurial opportunities, and thus contributes to economic and social development (Rothaermel et al., 2007; Centobelli et al., 2019).

The Public University of Navarre (hereinafter UPNA) embodies this ‘Entrepreneurial University’ spirit wholeheartedly, willing to act as a bridge between knowledge generation and socio-economic development. This resoluteness manifests itself in a strong commitment to R&D&i, in the promotion of innovative initiatives, and in the consolidation of an entrepreneurial culture that seeks to inspire UPNA community to channel their talents towards business creation.

Framed within the context of ‘Entrepreneurial University’, this work focuses on business initiatives arising from academic research results. In particular, the firms studied are all UPNA spin-offs. The objective is to highlight a series of common aspects that configure the characterization of this kind of firms, in accordance with the literature on the subject (i.e., Ortín et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2012). In addition, through a comparative case study, the aim is to identify the main challenges these companies face, as well as to determine the role that the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem fostered by UPNA plays in how these spin-offs face and overcome said challenges. Diverging from the focus on this particular University, the purpose is also to provide conclusions applicable to the generality of firms that fall into the category of university spin-offs.

In the following sections, we will describe the analytical framework designed for drawing conclusions regarding the characterization of academic spin-offs within the case study. Later, the main methodological aspects of qualitative research will be explained and the the spin-offs that conform the multiple case study will be presented. The following sections focus on the discussion of the findings derived from said case studies. First, we provide an analysis on the common features identified, in order to advance a comprehensive characterization of academic spin-offs, and to determine the main challenge faced by these firms. Second, we will present an overview on the UPNA Entrepreneurship Ecosystem; in particular, on the actions aimed at supporting the creation and sustainability of academic spin-offs, in order to offer deep understanding on how this Entrepreneurship Ecosystem might help academic spin-offs to overcome the challenge previously identified. Finally, the conclusions of the study will be summarized.

Analytical Framework and Methodology

Analytical Framework

Fostering the creation of spin-offs is one of the main mechanisms by which ‘Entrepreneurial Universities’ generate knowledge and transfer it to society, thus contributing to innovation and technological advancement. Today, in the Spanish university scene, this mechanism for transferring research results is a consolidated reality, and many universities have specific actions and programs to support the creation of spin-offs (Iglesias-Sánchez et al., 2012).

For the purposes of this study, the term ‘academic spin-off’ refers to a company that commercially exploits technology and/or knowledge resulting from research carried out in a university, whose creation usually implies the participation of the academic staff involved in said research and the support of the University within which it originated. The aforementioned characteristics have been pointed out in several works dealing with the definition and taxonomy of academic spin-offs –see, for instance, Leitch & Harrison (2005): Löfsten & Linderlöf (2005).

In order to guide the data analysis, an early state of the research contemplated the design of a framework based on relevant literature on the academic spin-off phenomenon (i.e., Ortín et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2012; Rodeiro et al., 2012). Said framework intends to offer a comprehensive guide of the meaningful aspects that should be examined in order to offer a compelling characterization of the UPNA spin-offs.

In this sense, Ortín et al. (2008) highlight aspects related to the founding team members, in terms of their motivation for launching the entrepreneurial initiative, the assessment of their entrepreneurial experience, and their general profile, extending this consideration to the expanded team with subsequent incorporations. This work also pays attention to the characteristics of the financial resources used by the spin-offs, with special emphasis on the aids received. Information on size and age of the firms is also provided.

Iglesias et al. (2012) rely also on relevant research to extract key analytical elements for the characterization of the spin-offs in their sample. The authors study aspects related to the casuistry of spin-offs, such as the intensity of their dedication to R&D&i activities, their participation in networks, the external support received, and financing particularities, distinguishing between investments in capital, financial aids and incomes.

Taking into account the above, the analytical framework for studying the characterization of academic spin-offs contemplates the following specific aspects:

• Origin and team

• R&D&i activity and networks

• Financing

• Business model

Size and maturity are equally prominent aspects in the literature for the characterization of this type of firms. In this work, a certain correlation between size and maturity can be observed, and we have chosen to consider these data transversally for the analysis of the other aspects listed.

Methodology

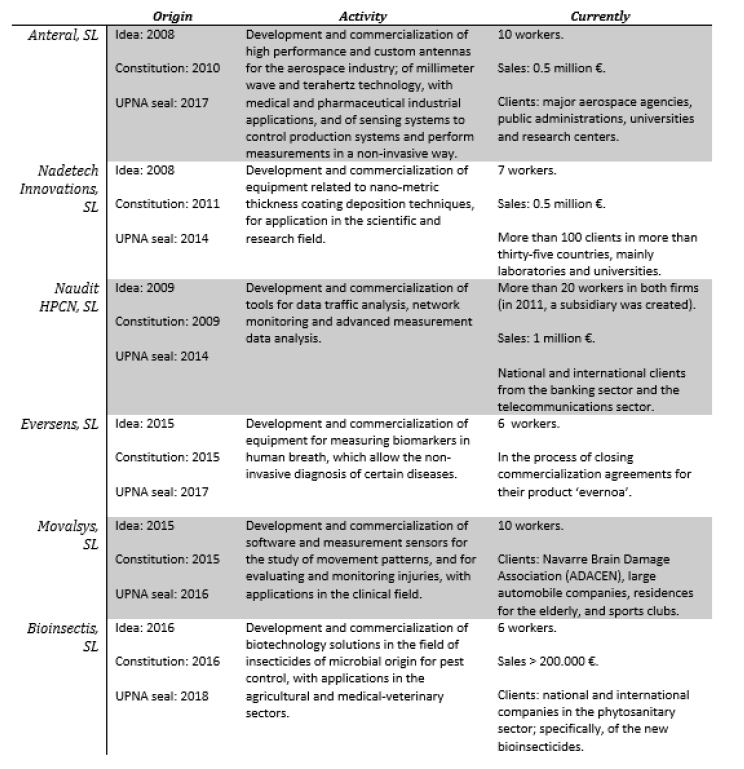

This work studies several entrepreneurial initiatives arising from research activities carried out at UPNA. These initiatives originated in the University, but acquired their own entity and today contribute to the generation of employment, value and progress in their environment. In particular, the six firms contemplated in this study were created within a period of seven years, obtained the UPNA spin-off qualification between 2014 and 2018, and are diverse in terms of maturity and fields of activity. However, all of them carry out businesses related to the commercial exploitation of advanced technology originated within the academic research of their promoters.

This study adopts a qualitative approach, the purpose being to draw conclusions regarding the idiosyncrasy of university spin-offs phenomenon through a multiple case study.

Although it is important to recognize the limitations of the qualitative methodology based on case studies, especially with regard to the generalization of the results, it is also true that this methodology is very appropriate to deepen the understanding of complex phenomena and to carry out inductive research (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2003). In addition, the multiplicity of cases used is a method that favors triangulation (Jick, 1979) and the generality of the results (Yin, 2003), providing robustness to the research (Herriot & Firestone, 1983).

Information was gathered through semi-structured interviews with founding partners and employees of the companies, as well as by comparing the documentation presented when applying for the official UPNA spin-off recognition. In addition, sources such as press releases, sector reports and financial data complemented the information. Subsequently, individual reports were drawn up for each of the six firms, with the aim of conducting an analysis for each case (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2003). Finally, a comparative study was conducted based on these reports.

Annex I shows a table synthetizing the identifying aspects of the six spin-offs of the study.

Characterization of University Spin-Offs

Origin Y Team

UPNA research staff fostered all the firms in the study. Two were the main objectives pursued by the founders when deciding to embark on an entrepreneurial project; i.e., technology transfer and talent retention. These motivations respond to the idiosyncrasy the academic entrepreneur, for whom the achievement of economic results and social status is not as attractive as being able to exploit a business opportunity detected in connection with their scientific-technical discoveries (Ortín et al., 2008).

"Anteral was created mainly for two reasons: one, to transmit all the knowledge that had been generated in the Antennas Research Group; and second, to retain the talent that was being trained both in the research group and the University as a whole." (I.M., CEO of Anteral)

"The objective was to create a company so that Navarrese people would have challenging and relevant work offers, so that they would not have to go abroad." (E.M., founding partner of Naudit)

As a rule, the UPNA academics behind these initiatives continue to this day as part of their respective projects. Previous studies highlight this aspect –i.e., the permanence of the human team throughout the trajectory of academic spin-offs– as a characteristic of these firms (Mustar, 2000; Ortín et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2012). It should be noted at this point that all spin-offs studied here have consolidated their teams recruiting professionals related to UPNA, mainly graduates from different levels of studies. Many of these incorporations are a result of mentoring internships or final year dissertations. In fact, the internship is very a common formula in the composition of academic spin-off teams (Ortín et al., 2008; Iglesias et al., 2012). Thus, UPNA spin-offs have consolidated a configuration of highly trained teams, with a clear scientific-technical profile and, with few exceptions, with a staff made up mostly of men. In this sense, Iglesias et al. (2012) contrast the small size of this type of firm with its ability to bring together a high percentage of highly qualified personnel, highlighting the representation of professionals with a Ph.D. degree, followed by personnel with a high technical degree. The high qualification of the staff is also concentrated around scientific-technical fields, so that academic spin-offs normally suffer from a notable lack of experience in management (Ortín et al., 2008).

These considerations notwithstanding, several companies in this study express the convenience of guaranteeing a certain level of multidisciplinary in their teams.

"We are a multidisciplinary team; we come from very different fields: mathematics, computer science, telecommunications, sports medicine, physiotherapy, geriatrics... We have the knowledge, we have the technology, and we are convinced that what we do matters, because it helps a lot of people." (M.V., founding partner and CEO of Movalsys)

Likewise, the researchers who founded Anteral contacted a an expert in management from outside UPNA to become part of the founding team, since the lack of knowledge in this area had been perceived by part of academic partners as a major impediment. Other spin-offs in the study reached similar conclusions as they progressed in their business trajectory. In this sense, in 2018, a new CEO entered Nadetech, an engineer UPNA graduate with years of experience in commercial and management areas.

In short, it should be noted that as UPNA spin-offs reach maturity, there is a tendency to expand the teams and diversify the profile (both in terms of gender and in terms of fields of knowledge), although maintaining a highly qualified staff.

R&D&I Activities and Networks

All spin-offs in the study are technology-based companies, whose business idea strongly identifies with the development of innovative technologies. Therefore, the firms show a clear commitment to innovation culture and to R&D&i activities. Besides, all out of them carry out said activities with the participation of external agents.

Indeed, and in line with the open innovation paradigm coined by Chesbrough (2003), a large part of the innovative practices developed by companies are not institutionalized activities within internal R&D departments; instead, these practices tend to imply networks that involve agents of various kinds (Som et al., 2012). It is evident that this paradigm has one of its most notorious expressions in the transfer of knowledge and technology from University towards the industry. Thus, the very essence of the ‘academic spin-off’ concept embodies the considerations of the open innovation phenomenon.

From another viewpoint, it is worth highlighting that all the firms maintain a close institutional relationship with UPNA articulated mainly through the joint development of research projects, the formalization of technology transfer agreements and the hiring of graduates. In addition, five of the six companies use the equipment and facilities of UPNA for the development of their activity.

As an example, Bioinsectis has access to equipment and spaces at UPNA through the formalization of technology transfer agreements and maintains close a collaboration for the development of R&D activities with the Crop Protection Research Group and the Institute of Agrobiotechnology of UPNA. This collaboration was foreseen as preferred by the company from the conception of the business idea.

“The initial expectation was that the company would be able to collaborate with the Crop Protection Research Group in R&D projects, in addition to training staff through the mentoring of graduate research dissertations and Ph. D. thesis. This is contemplated in a collaboration agreement signed between the spin-off and UPNA. To date, the degree of compliance has been optimal.” (P.C., founding partner of Bioinsectis)

According to the study by Iglesias et al., (2012), academic spin-offs often use the formula of collaborative projects for the development of their R&D&i activities, thus involving scientific staff from the research group from which they emerged. In short, the strength of the links between UPNA and its spin-offs aligns with conclusions highlighted in the literature (e.g., Johansson et al., 2005; Soetanto & Jack, 2016). Unlike other types of start-ups, academic spin-offs maintain ongoing relationships with their institution of origin, ranging from informal relationships –i.e., welcoming graduates into the spin-off staff–, to more formal relationships –i.e., via technology transfer agreements (Johansson et al., 2005). In any case, the support of the parent institution plays an essential role at several levels, including aspects such as advice in both technical and commercial areas and intermediation in financing issues, among others (Iglesias et al., 2012), giving rise to a symbiotic relationship from which both the University and the spin-off benefit.

“Since the creation of Naudit, we deemed it important that our universities were part of the development of the firm. The achievements at Naudit should translate to the universities that have trusted us throughout these years.” (E.M., founding partner of Naudit)

Also, the R&D&i practices carried out by this type of firms do not participate in this open paradigm solely because of their connection with their institution of origin, but rather encompass a broader catalog of activities and participating agents (Lubik et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2018). In this sense, R&D&i activities in UPNA spin-offs are developed through collaborative projects with clients, suppliers, other research centers and other firms.

For instance, Eversens values highly their collaboration with agents from medical institutions, such as specialists in allergology and asthma biomedical research centers. This collaboration has been essential for both the development and validation of its "evernoa" product, tested with asthmatic patients in hospital centers.

“Within the health sector, we believe that we are in a good community: hospitals are getting involved with us.” (J.M.P., founding partner of Eversens)

In short, academic spin-offs have an open attitude to collaboration, to the development of alliances and the use of synergies, consolidating networks with strategic agents of innovation and entrepreneurship systems (Iglesias et al., 2012).

Financing

With regard to the start-up of the firms in this study, the initial social capital consisted almost entirely of contributions made by the academic entrepreneurs who promoted the initiative. This is aligned to the trend detected for academic spin-offs, in which the main contribution to capital is the founders' own savings (Ortín, 2008; Rodeiro et al., 2012).

However, partners outside the project entering the capital of academic spin-offs is a source of financing for which there is a growing trend, especially in the early stages of development of these firms (Iglesias, 2012). Among these external partners, the participation of the institution of origin stands out, which is very significant inasmuch as it stands as one of the main mechanisms to promote the objectives of the ‘Entrepreneurial University’. Although it is an underdeveloped instrument, its advantage transcends the mere financial sphere, since it implies the involvement of an institution with a great knowledge of the problems, equipment and technology of the initiative (Rodeiro, 2012). Indeed, of the six companies analyzed here, five of them have UPNA participation in their capital, albeit with modest participation percentages, which range between 4% and 5%.

In addition, several spin-offs count with the participation of other agents, such as ‘family, friends and fools’, industrial partners and, especially, investment funds and venture capital companies. These are sources of a very heterogeneous nature, in terms of accessibility, cost and implications. The low cost and ease of access represented by the savings of close people contrast with the traditional limitation of this type of resources, which in any case are usually the first source that entrepreneurs turn to (Rodeiro et al., 2012). On the other hand, the participation of industrial partners depends on the knowledge and skills that the new agents incorporate into the firm complementing its needs. This is the case of Naudit, which in 2011, and with the aim of separating the commercialization of their products and services from R&D&I activities, constituted a subsidiary company. Regarding the creation of this new company, two experts in business management in the ICT sector joined the project as partners.

“The participation of external partners is not valued in terms of financing; it is valued in terms of the technical or commercial contribution that they can provide.” (E.M., founding partner of Naudit)

Finally, it is worth mentioning financing through capital investments made by venture capital entities, investment funds and, as a hybrid instrument, participative loans. For example, Eversens has received capital contributions from a public venture capital company, a semi-public investment fund, and a private fund. This type of mechanism is a very attractive solution in the early stages of academic spin-offs, given the limitations of the aforementioned resources and as an alternative to traditional debt (Rodeiro et al., 2012). However, literature indicates a certain weakness in the presence of private institutions of this nature (Iglesias et al., 2012), so that the dynamisation by public or semi-public agents becomes a very relevant aspect of the ecosystem that supports this type of companies, as will be discussed later.

Subsidies and aids for the development of R&D&i activities are other typical forms of financing academic spin-offs, which implies the participation of different state and regional administrations and, to a lesser extent, institutions of the European Union (Ortín et al., 2008; Rodeiro et al., 2012). Among the UPNA spin-offs, it is clear that access to this type of resources is essential for the advancement of the different initiatives.

“The firm has received different grants for the development of R&D activities, in calls for European programs, such as H2020, and from the Government of Navarre, in collaborative projects with research centers, the UPNA and other agents, as well as grants for the hiring technologists and personnel.” (J.M.P, founding partner of Eversens)

“Thanks to the intensive R&D activity carried out in the firm, we have received several aids, through industrial doctorate programs and transfer projects of the Government of Navarre, as well as from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities.” (P.C., founding partner of Bioinsectis)

Business Model

The commercial activity of academic spin-offs stands out for its tendency to specialization (Rodeiro et al., 2012), since they usually serve market niches with very particular technological needs. They also tend to function emulating the dynamics of university research groups (Iglesias et al., 2012), in the sense that they usually become the external R&D department of other agents. However, these trends coexist with another of a reforming nature, since it these companies undergo a permanent reconfiguration, in order to reorient their service and product portfolios and adapt their business models to the changing needs arising in their trajectories. (Iglesias et al., 2012; Clausen & Rasmussen, 2013).

The cases in this study reveal notable changes in the strategies and business ideas of the UPNA spin-offs. As they mature, these firms let go the focus on a value proposition based on basic research and the exploration of disruptive technologies, and open up to the commercial exploitation of its technological results.

As an example, several years after the start of its activity, Anteral verified that the application of terahertz technology for production techniques was a line that required great efforts in R&D, which was hard to profit from, since it implies a non-mature. As an alternative, the company decided to focus efforts on Industry 4.0, developing its own radar systems, which could lead to a more marketable product. Since 2017, they began to develop radar technology for innovative applications, giving rise to the uRAD line and commercializing products that are nowadays acquired by large aerospace agencies and research centers. In the same way, Nadetech is currently in the process of implementing a strategic plan with the aim of systematizing and professionalizing the operation of the company. On the one hand, they intend to consolidate the traditional business line, aimed at the segment of universities, laboratories and clients of the scientific-researched sector; and on the other, the strategic plan foresees the need to scale to industrial solutions.

“The firm has been operating since its inception without a too defined strategy and hardly doing any commercial work. Nadetech has potential for much more. Now is the time to grow up.” (J.A.R., CEO of Nadetech)

In a similar vein, Naudit began its journey by offering highly specialized, personalized and high-value solutions related to traffic analysis consulting and to the inspection and quality assurance of communication networks. In 2011, as noted, the subsidiary Naudit Ingeniería, SL was created, and two partners who were experts in business management in the ICT sector entered the project. The incorporation of these partners and the delimitation of commercial activities promoted the definition and expansion of the client portfolio. While at the beginning, the offer aimed mainly at telecommunication operators and the public sector, from 2011 on Naudit devoted efforts to include clients in the banking sector.

Eversens shows an earlier reconfiguration of its business model. The initiative started with a business idea aimed at the development of technology and the design of different devices. However, it was soon decided that it would be more convenient to focus efforts on the commercialization of a specific equipment. Regarding the revenue model, they contemplated selling their equipment to agents in the health and pharmaceutical sectors, offering the device at a reduced cost and charging mainly for consumables. This model, which remains in force, was perceived as feasible only at a regional level, therefore, it was later complemented with a second route, through which the company pursues the sale of devices and consumables to specialized distributors. It should be noted that the entry of equity partners, such as the mutual funds and venture capital companies mentioned above, influenced the early reorientation of the business strategy in Eversens.

“At first you think that things are easier, that the technical developments and the products you have are enough. But reality is that once you have that, there is still a great job to do to materialize what you've been working on for so many years.” (J.M.P., founding partner of Eversens)

In short, the spin-offs of this study have experienced the need to focus their efforts on practices that guarantee turnover through the exploitation of knowledge and technology in new markets, as opposed to a first vocation more oriented to basic research and technological exploration undoubtedly deriving from the academic environment in which the initiatives arose.

As a summary, the following list of aspects configure the characterization of UPNA spin-offs and, inductively, serves also as a general characterization proposal applicable to the academic spin-offs phenomenon:

• Origin and team

o Motivation: Knowledge transfer and talent retention.

o Profiles: Highly qualified, scientific and/or technical, and mainly male. Diversity increases as firms mature and teams grow.

• R&D&i activities and networks

o Intense, due to its nature of technology-based companies.

o Close ties with UPNA and other external agents for the development of these activities.

• Financing

o Participation in social capital as a tool to incorporate knowledge and expertise from diverse agents.

o Aids for the development of R&D&i projects.

• Business model

o From a strategy purely based on exploration towards commercial exploitation of the technology.

The Challenge of Ambidexterity and the Role of University Entrepreneurship Ecosystem

The comparative analysis above not only the identification of the most representative characteristics of academic spin-offs, but also of the main challenges they face. In this sense, the findings point to the difficulties arising in the search and consolidation of a sustainable business model that combines the use of the disruptive innovative capacity of these initiatives with the sustainable exploitation of their research results. This problem is due to the particular idiosyncrasy of this type of firms, deeply linked to R&D and the modus operandi of their institutions of origin, largely dependent on public funding for the development of these tasks, and with eminently technical teams who usually lack managerial and commercial experience.

In line with the arguments in favor of the ambidextrous company (e.g., Gupta et al., 2006), it has been pointed out that university spin-offs, which normally face higher levels of uncertainty than other startups, ups, should combine exploration strategies with exploitation strategies (Soetanto & Jack, 2016).

The Challenge of Ambidexterity in University Spin-Offs

As noted before, management deficiencies are common in academic spin-off teams. Literature has devoted efforts to analyze this phenomenon, linking the failures of this type of firms with problems in the management team and not with the suitability of the technology or the business opportunity (Timmons, 1994). In this sense, it is particularly important to focus on the figure of the university entrepreneur, who is generally the creator of the technology that sparks the business idea (Rodeiro et al., 2008). This figure also faces considerable challenges, especially considering that their professional experience and personal skills are not usually aligned with the demands in the field of business management (Miller et al., 2018).

This way, the studies highlight the complexity of the creating firms derived from the scientific-university field, which need handle both technical challenges and organizational efficiency. These challenges deepen because the people in charge of academic spin-offs lack in most cases a market orientation, which constitutes a significant disadvantage (Gómez et al., 2007). In fact, founders and managers of these firms declare themselves aware of said disadvantage (Ortín et al., 2008), also informing of a feeling of ‘loneliness’ (Rodeiro et al., 2012) in the face of the uncertainty in the market and regarding the approach to the business strategy.

For this reason, literature has pointed out that the heterogeneity in terms of technical and management profiles in the teams in charge of the academic spin-off has been influences their chances of success (Ortín et al., 2008). In this sense, these firms tend to complement the founding team tends with professionals in commercial and business management (Vanaelst et al., 2006, Rodeiro et al., 2012).

Our case studies illustrate these particularities; i.e., the main deficiency in management areas detected in the human teams of the spin-offs, and the tendency to diversify them as the companies mature, in order to promote the entry of people with profiles complementary to the eminently scientific-technical ones of the founders.

After all, academic spin-offs originate from the development of scientific-technological solutions, through intensive R&D processes in research departments, so the germ of the idea does not reside inasmuch the detection of a need in the market as in obtaining said solution (Fuentelsaz et al., 2017). Thus, these types of initiatives are much more prone to strategies for exploring disruptive technologies than to exploitation strategies (Colombo et al., 2015). This is due both to the particular composition of their teams, and to the fact that these companies tend to maintain very close ties with their institutions of origin and the scientific community in general. These ties grant them privileged access to key knowledge for the development of cutting-edge technology, but at the same time, this keeps them away from a way of management that makes these proposals efficiently marketable and profitable.

Bearing this in mind, the success of academic spin-offs depends on their abilities to combine the maintenance of their competitive advantage based on the development of high technology with organizational and commercial skills that allow them to succeed in the positioning of their business models (Ortín et al., 2008). In short, it is all about balancing the two strategies –i.e., the exploration of new opportunities and the exploitation of old certainties– identified by March (1991). These strategies benefit from vast development in relevant literature on innovation management and that rule under fundamentally different logics; thus, their coexistence generates strong tensions in organizations, since they compete for the same resources (He & Wong, 2004). However, literature has highlighted that the synergistic effect between the two mentioned strategies may be beneficial, arguing in favor of the development of ambidextrous strategies, which imply the dedication of effort and resources both to the development of new disruptive technologies, and to exploiting the knowledge base of the company (e.g., He & Wong, 2004; Gupta et al., 2006).

The convenience of combining exploration and exploitation strategies with in the particular case of academic spin-offs has also been addressed (Soetanto & Jack, 2016). In this sense, the study by Clausen & Rasmussen (2013) concludes that the most innovative and successful spin-offs in the commercialization of research results are those that establish complex business models. This study emphasizes the different potential applications associated with the same technology, and links the ability to create value from radical innovations with the ability to articulate different business models that take advantage of the complementarity among the different alternatives for exploiting said radical technologies.

The Role of University Ecosystem in Overcoming the Challenge of Ambidexterity

Once we have identified the main challenge for academic spin-offs –i.e., the need to manage ambidextrous strategies–, this study intends to determine the role of the university Entrepreneurship Ecosystem when offering academic spin-offs tools to face the said challenge.

In this sense, previous literature (e.g., Hayter et al., 2018) collects a wide variety of instruments and actions through which universities may support entrepreneurship. With regard to academic entrepreneurship in particular, the technology transfer offices play a fundamental role, as do other types of infrastructures such as incubators or science parks, and other actions such as financing companies through university seed funds.

UPNA articulates a great variety of these instruments, acting on many occasions hand in hand with the institutions and instruments of the regional public administration, creating an ecosystem to support entrepreneurship that aims to promote the creation and development of business initiatives. This way, internal agents such as the Research Service and the Vice-Rector's Office for Students, Employment and Entrepreneurship coordinate with external agents such as the European Center for Business and Innovation of Navarre (hereinafter CEIN), the Company for the Development of Navarre (hereinafter SODENA), the Government of Navarre or banking institutions to stimulate and promote the aforementioned actions.

Focusing now on the particular used by the spin-offs in this study, it is worth noting that their implementation has benefited greatly from business incubation services. In this sense, Navarre start-ups have access to the CEIN Business Incubator. Among the spin-offs of this study, Eversens, Movalsys and Nadetech profited from said service.

In addition, the EIBT (Innovative Technology-Based Companies) Network of Navarre recognized several of the UPNA spin-offs. This network granted awards to Nadetech in 2008 and to Anteral in 2011, which is an instrument used by the Government of Navarre through CEIN, and implied an economic endowment destined to the maturation of the idea and the start-up of the firms.

“The acceptance of the project within the scientific-technological framework of Navarre through the EIBT network was an important spur to make the final decision to start the activities.” (Information on the application to be an UPNA spin-off, Nadetech).

Regarding the mechanisms for accessing to financing, all spin-offs of the study highlight their relevance. The investment funds of the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem play a very important role in this regard, as indicated in the characterization of the companies in the study. The social capital of Eversens is participated by institutions such as Start Up Capital Navarra and SODENA. As for Nadetech, SODENA stands out as one of the most relevant agents when it comes to providing help to overcome obstacles, due to the support provided to access the Navarre Tech Transfer investment fund.

Besides financial support, spin-offs value highly instruments related to training and advice. In particular, the firms highlight the services offered by CEIN; and among them, especially those programs that offer business advice:

“During our stay at CEIN, we expanded the knowledge received by participating in various events aimed at MEDTECH companies. The actions were aimed at regulatory, marketing, negotiation and sales issues.” (J.M.P, founding partner of Eversens)

“Specifically, the most interesting [courses and services] have been those related to personal development, and a joint reflection on business strategy.” (J.A.R, CEO of Nadetech)

As stated before, academic spin-offs characteristically tend to focus on exploration strategies to the detriment of exploitation strategies; and yet, the success of these initiatives has been linked to the ability to manage resources and tensions in order to combine the development of disruptive technologies with the commercial exploitation of the knowledge generated.

The trajectories of the UPNA spin-offs show how they have undergone notable changes in their business models in terms of the design of marketing strategies for their highly specialized technologies. In addition, the comparative study highlights that this openness to commercial strategic visions are related to the use of the support instruments of the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem.

“The business model of these projects is evolving constantly (...). Very often, the firm is created before fundamental aspects of the business model are determined. Thus, there is usually a need for a reorientation because, founders need participate in programs to evaluate and redefine the business model (...) and receive the necessary reorientation, advice and training.” (L.N., CEIN technician)

“There has been a wide training offer through talks, both at the CEIN and at the UPNA, in which experts in different areas have shared their experience and knowledge. For Movalsys, the most interesting sessions have been related to economic and financial aspects.” (M.V., founding partner and CEO of Movalsys)

Finally, it is worth noting that the spin-offs participated by institutions such as investment funds benefit from being in touch with these partners that come from outside the academic field, beyond the mere financing aspect.

“Financing is essential to execute the plans; even so, we have always sought investors who can contribute more than just money. Specifically, our investor Navarra Tech Transfer is providing us with contacts of interest and support in management, helping to professionalize the company.” (J.A.R., CEO of Nadetech)

The UPNA spin-offs, therefore, have benefited from the support provided by Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in different and crucial phases of their trajectory, and they recognize their influence in the promotion and development of their business idea. Regarding the use of the various instruments and programs to face the challenge of ambidexterity in particular, the mediating role of the Ecosystem stands out, as it enables the development of management skills and a commercial vision and, in general, it fosters an ongoing reevaluation of the business model.

Conclusion

This paper has offered a comparative analysis on six firms spurred from research activities in the academic field, in order to determine a series of common features that could configure the characterization of this kind of companies, and thus provide a contribution to complement the studies on the phenomenon of academic spin-offs and their idiosyncrasy. In turn, this study also intended to identify the main challenges these companies face, and to carry out an exploratory study on how the Entrepreneurship Ecosystem helps to overcome these challenges.

As a summary, the following aspects configure a characterization proposal applicable to the academic spin-offs phenomenon:

• The motivations driving the creation of academic spin-offs are the transfer and commercial exploitation of knowledge and technology, on the one hand, and the generation of job opportunities to retain talent in the region, on the other.

• The profile of the academic entrepreneur is a male professional, highly qualified in scientific-technical areas. Diversification in this profile, both in terms of gender and in of areas of expertise, arises as companies mature and teams expand.

• Academic spin-offs show a marked commitment to innovation culture and to R&D activities. These companies participate in collaborative projects with their institutions of origin and also with clients, suppliers, other research centers and other companies.

• Academic spin-offs maintain a close relationship with the universities from which they emerged. In addition to the continuous development of joint research projects and the usual formalization of technology transfer agreements, the teams in these firms usually come from their universities, and the latter tend to provide their spin-offs with equipment and facilities for the development of their activity.

• To start-up the initiatives, academic spin-offs are financed mainly with their founders’ savings; however, it is worth highlighting the participation of funds contributed by various agents, such as the universities of origin, industrial partners and investment funds.

• Another representative and generalized form of financing in the phenomenon of university spin-offs is the aid for the development of R&D&I activities, granted by the different supranational, state or regional administrations.

• Academic spin-offs, throughout their trajectory, undergo profound changes in their business strategies and ideas. In general, they experience the need to refocus towards exploiting knowledge and technology in new markets, in contrast to an early vocation more oriented to basic research and technological exploration.

Once the most representative characteristics of the UPNA spin-offs had been determined, the comparative study delved into the identification of the main challenges they face. The conclusions of the analysis indicate the difficulties related to the business model change described in the last point of the characterization; that is, regarding the need to combine the practice of exploring disruptive technologies with the need to guarantee a sustainable model of commercial exploitation of the products developed by these spin-offs. Therefore, in this study the main challenge of the UPNA spin-offs has been stated as the challenge of ambidexterity.

Indeed, academic spin-offs are technology-based firms closely linked to the work of their home institutions, with technical profiles that often present notable deficiencies in management areas. In this sense, they are more likely than other types of companies even other types of technology-based start-ups–to get stuck in strategies that prioritize basic research and the exploration of disruptive knowledge. The difficulties in adopting a market vision therefore lead to a greater incidence in this type of companies to replicate the modus operandi of the research departments of the universities and end up becoming laboratories that provide R&D services to other agents.

However, studies link the success of these initiatives to the ability to manage resources and tensions in order to carry out an ambidextrous strategy. Thus, learning to combine exploration and exploitation perspectives skillfully becomes paramount when pursuing to consolidate businesses arising from the academic field.

The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem energized by each particular University acquires a special relevance in overcoming this challenge of ambidexterity. Thus, finally, this paper concludes on the relevance of the Ecosystem instruments aimed at filling the initial shortcomings of academic spin-offs in management and commercial strategy matters, both via the participation in training programs, and through the entry into the capital stock of investment companies that, in addition to financing, offer advice.

Annex I: Upna Spin-Offs

References

Carayannis, E.G.Y., & Campbell, D.F.J. (2009). “Mode 3” and “quadruple helix”: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. International Journal of Technology Management, 46, 201-234.

Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., Esposito, E., Shashi, Y. (2019). Exploration and exploitation in the development of more entrepreneurial universities: A twisting learning path model of ambidexterity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 141, 172-194.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Chesbrough, H. (2003). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Clausen, T.H., & Rasmussen, E. (2013). Parallel business models and the innovativeness of research-based spin-off ventures. Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(6), 836-849.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Colombo, M.G., Doganova, L., Piva, E., D’Adda, D., & Mustar, P. (2015). Hybrid alliances and radical innovation: the performance implications of integrating exploration and exploitation. Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(4), 696-722.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (1995). The triple helix–university-industry-government relations: A laboratory for knowledge based economic development. EASST Review, 14(1), 11–19.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fuentelsaz, L., González, C., Maícas J.P., & Mata, P. (2017). What came before, science or the market? The market orientation of university spin-offs. Economía Industrial, 404, 53-62.

Gibbons, M. (1997). What kind of university? Research and teaching in the 21st century. En: Universities and the Future-Government Policy Options Regarding Québec Universities. Ministère de l’Éducation, Gouvernement du Québec.

Gómez, J.M., Mira, I., Verdú, A.J., & Sancho, J. (2007). Academic spin-offs as a means of technology transfer. Economía Industrial, 366, 61-72.

Gupta; A.K., Smith, K.G., & Shalley, C.E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 4, 693-706.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Hayter, C., Nelson, A., Zayed, S., & O´Connor, A. (2018). Concepualizing academic entrepreneurship ecosystems; a review, analysis and extension of the literature. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(4), 1039-1082.

He, Z.L.Y., & Wong, P.K. (2004). Exploration vs. exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organization Science, 15(4), 481–494.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Herriot, R.E., & Firestone, W.A. (1983). Multisite qualitative policy research: optimizing description and generalizability. Educational Researcher, 12(2), 14-19.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Iglesias Sánchez, P., Jambrino Maldonado, C.Y., & Peñafiel Velasco, A. (2012). Characterization of university Spin-Offs as a technology transfer mechanism through a cluster analysis. European Journal of Business Management and Economics, 21(3), 240-254.

Jick, T.D. (1979). Mixing qualitative and quantitative methods: Triangulation in action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(4), 602-611.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Johansson, M., Jacob, M., & Hellström, T. (2005). The strength of strong ties: University spin-offs and the significance of historical relations. Journal of Technoly Transfer, 30(3), 271-286.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Leitch, C.M.Y., & Harrison, R.T. (2005). Maximising the potential of university spin-outs: the development of second-order commercialisation activities. R&D Management, 35(3), 257-272.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Löfsten, H.Y., & Lindelöf, P. (2005). R&D networks and product innovation patterns academic and non-academic new technology-based firms on Sciences Parks. Technovation, 25, 1025-1037.

Lubik, S., Garnsey, E., Minshall, T., & Platts, K. (2013). Value creation from the innovation environment. R&D Management, 43(2), 136-150.

March, J.G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87.

Miller, K., McAdam, R.Y., & McAdam, M. ( 2018). A systematic literature review of university technology transfer from a quadruple helix perspective: Toward a research agenda. R&D Management, 48(1), 7-24.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Mustar, P. (2000). University Spin-Off. In OECD Workshop on high-technology Spin-Off. Association of University Technology Managers.

Ortín-Ángel, P., Salas, V., Trujillo, M.V., & Vendrell, V. (2008). The creation of university spin-offs in Spain: characteristics, determinants and results. Economía Industrial, 368, 79-95.

Rodeiro Pazos, D., & Calvo Babío, N.Y. (2012). Business management as a key development factor for university spin-offs. Economic and financial analysis. Management Notebooks, 12(1), 59-81.

Rothaermel, F.T., Agung, S.D.Y., & Jiang, L. (2007). University entrepreneurship: A taxonomy of the literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 16(4), 691-791.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Soetanto, D.Y., & Jack, S. (2016). The impact of university-based incubation support on the innovation strategy of academic spin-offs. Technovation, 25-40.

Indexing at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Som, O., Diekmann, J., Solberg, E., Schricke, E., Schubert, T., Jung-Erceg, P., Stehnken, T., & Daimer, S. (2012). Organisational and Marketing Innovation-Promises and Pitfalls. INNO-Grips II report. Brussels: European Commission, DG Enterprise and Industry.

Timmons, J.A. (1994). New Venture Creation: Entrepreneurship for the 21st Century. Fourth edition. Irwin Press, Burr Ridge, IL

Vanaelst, I., Clarysse, B., & Wright, M. (2006). Entrepreneurial team development in academic Spinous: An examination of team heterogeneity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30, 249-271.

Wright, M., Birley, S., & Mosey, S. (2004). Entrepreneurship and university technology transfer. Journal of Technology Transfer, 29, 235-246.

Yin, R. (2003). Case study research, Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Received: 11-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-11294; Editor assigned: 14-Feb-2022, PreQC No. AEJ-22-11294(PQ); Reviewed: 24-Feb-2022, QC No. AEJ-22-11294; Revised: 20-Mar-2022, Manuscript No. AEJ-22-11294(R); Published: 01-Apr-2022