Research Article: 2022 Vol: 26 Issue: 2S

Advanced cost accounting systems within the lean thinking strategy: A theoretical analysis

Ali Hazim Alyamoor, University Of Mosul

Citation Information: Alyamoor, A.H. (2022). Advanced cost accounting systems within the lean thinking strategy: A theoretical analysis. Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 26(S2), 1-9.

Abstract

The primary aim of the research is to highlight the advanced cost accounting systems that are more suitable for the lean thinking strategy. These systems are Throughput Accounting (TA) and Value Stream Costing (VSC). To achieve the research aims, I conducted a theoretical analysis of the literature covering both systems and discussed the superiority of these systems over others under the lean thinking strategy. The research found that the implementation of such systems requires a radical change in organizations to be able to support the lean thinking strategy and adding value for customers. Also, these systems should be implemented as a complement to, and not as a substitute for the traditional costing system. The research contributes to the advanced costing systems literature as it provides a holistic and comparative analysis of both TA and VSC, which would be useful to academics and practitioners.

Keywords

Advanced Cost Accounting Systems, Lean Thinking Strategy, Throughput Accounting, Value Stream Costing, Theoretical Analysis.

Introduction

The business environment in the last two decades has been witnessed significant developments due to the development of economic, social, political, and technological factors. Today business environment is characterized by dynamic, complex and rapid changes. To cope with this environment, organizations need to be proactive, agile and resilient in managing their business and providing their services and products to customers (Kumar & Nagpal, 2011). Indeed, organizations in different sectors have tended to adopt various continuous improvement initiatives such as lean thinking, total quality control, Just In Time (JIT), six-sigma, and the theory of constraints. These initiatives are used by organizations to sustain competitive advantages in a certain market niche. These practices, as Fullerton, Kennedy & Widener (2013) indicate, are recognized as components of lean thinking strategy which is one of the most significant strategies in achieving world-class performance. However, cost management practices applied by organizations must be aligned with such a strategy to achieve its main objective. The traditional cost accounting system is not able to meet the requirements of lean thinking strategy as they rarely focus on flow through the process. It is argued that based on the lean thinking strategy, profitability is maximized when the rate of flow through the process is maximized, not when a machine or labor utilization is maximized. This implies that cost accounting systems need to deal with the flow by providing information that measure it and encouraging behaviors that enhance it. The cost of the product or services is associated with the flow through the Process and thus enhancing flow through the process leads to increases profitability. Within this context, organizations in different sectors are under pressure to provide high-quality products and services while increasing operational efficiency to reduce costs, improve speed and increase flexibility. To address these major challenges, organizations are increasingly turning to adopt the lean thinking strategy. This research shed light on the advanced costing systems, including Value Stream Costing (VSC) and Throughput Accounting (TA) that fit with the lean thinking strategy. The research reviews the literature of advanced costing systems by focusing on the ones that are most suitable for lean strategy and discuss their benefits and drawbacks. The rest of this research is organized as follow. Section 2 highlights the lean thinking strategy and its principles. In section 3, advanced cost accounting systems covering VSC and AT are examined. It discusses the superior of these systems within the lean thinking strategy over others. Section 4 compares the VSC with the TA from different aspects. The research is concluded in section 5.

Lean Thinking Strategy

Lean thinking is originally attributed to the Toyota production system that developed from Just-In-Time (JIT). Since then, the term has developed into a much wider operational strategy. The main objective of lean thinking is to decrease wastes, produce and deliver products of high quality, decrease the levels of inventory and streamline the process (Kennedy & Widener 2008). Lean thinking as DeBusk, (2015) defines is “an overarching philosophy or system focusing on delivering value to the customer, improving the flow of products or services, and eliminating waste, while maintaining respect for people”. According to Fullerton, Kennedy & Widener (2014), lean thinking represents one of the most significant strategies in achieving world-class performance. The core of lean thinking is the integration of all business functions and process into a unified, coherent system that use principles and tools to increase productivity and flexibility, reduce cost and provide more customer values. The main focus of lean thinking is reducing the non-value-added activities that represent wasteful from the lean thinking point of view. The wasteful activities could be related to overproduction waste, waiting’s time waste, transportation waste, inventory waste, product defects waste, processing waste, and waste of motion (Rahman et al., 2013). These wasteful activities work as barriers against the flow of the process to meet the customers need and provide value for them. Lean thinking depends on multi-dimensional approaches to improve the process of flow and eliminate waste. For example, in managing the production flow, both Kanban & Drum-Buffer-Rope (DBR) techniques can be used to control when new materials could be released to the floor (Albright & Lam, 2006). Thus, it can be said that the main thrust of lean thinking is that several practices can be correlated in an integrated system to reduce wastes. Womack & Jones (2003) determine that the lean thinking strategy depends on five main principles to eliminate wastes. These principles are:

First, the crucial starting point for lean strategy is value creation. This value can only be determined by the ultimate customers and refers to a specific product or service with specific capabilities and features offered at a specific price. So, customer needs and expectations should be determined and any activity that does not meet those expectations and needs should be categorized as waste.

Second, to create value for customers, all activities and tasks must be grouped in a value stream. The lean organization must be abandoned any functionally oriented and organized around value streams. A value stream refers to ‘the sequence of processes through which a product is transformed and delivered to the customer’. Thus, the value streams encompass all functions necessary to serve the customer and generate value such as designing, ordering, producing, delivering, and servicing (Fullerton, Kennedy & Widener, 2014). The focus of value streams is important for the lean organization as they generate money for them. The value generated for the customer will determine the organizations’ success or failure. Also, the value streams enable to determine wastes and to develop suitable action plans to eliminate them. Additionally, focus on the value stream will give a better view of the materials flow, information flow and cash flows inside the organization. This is also could be the best way to determine and improve the value being created for the customer, the best way to raise the business, increase sales and produced better results (Rosa & Machado, 2013). Thus, one of the main objectives of lean thinking is to increase and improve the contribution of the value streams (Fullerton, Kennedy & Widener, 2014).

Third, one of the main principles of the lean thinking strategy is managing production flow using the Kanban system. This system work as a tool for regulating production quantities. It requires production only if there is a demand for the product. In case of finishing a task, for example, the product moves to the next work-station but the operators and machines will not be active until they receive a Kanban signal card (Albright & Lam, 2006). The Kanban system is based on allowing customers to pull the products or services from the next upstream activity. The customer could be an actual customer that demands the finished product (external) or could be an operator that demands an unfinished product to proceed in the next station (internal). Thus, in this pulling system, the material will not be released until a signal from the customer is sent to do so (Rahman et al., 2013). This will effectively decrease the inventory of work in process and associated costs (Albright & Lam, 2006).

Fourth, with the pull system, Lean organizations concentrate on the flow of products through the whole system rather than focusing on improving performance in a specific department or work centre (DeBusk, 2015). The work is often fulfilled in organizations by establishing cells of workers and equipment. The equipment is organized in a sequence that reflects the steps of the process of transformation to allow a continuous flow of the work being carried out. The workers, on the other hand, are trained and empowered to perform all the tasks and activities within the cells. In these cells, the production of whole products depends on the cell of workers instead of depending on functional departments to transfer work in process sequentially over an assembly line. Workers are trained in the whole production process not only in one of its parts. So, it is significant to develop their team skills and continuous improvement practices (Fullerton & Kennedy, 2009; Kennedy & Widener, 2008; Carnes & Hedin, 2005). This structure of organization would lead to save time and space on the shop floor and improve tracking of products or services. Moreover, it gives them the flexibility and responsiveness they need in their relationships with their customer (Carnes & Hedin, 2005).

Fifth, as organizations adopt lean practices, it is obvious that improvement is an ongoing process. Approaches to reduce time, cost, effort and space and improve quality, delivery and productivity can be conducted continuously. Therefore, lean organizations should adopt a continuous improvement philosophy to encourage a culture of sustained improvement in performance (Ramasamy, 2005).

The benefits of using the principles of lean thinking are directly related to the excellence of operational performance as they improve flexibility, quality, and customer response time. These in turn should lead to an efficiency improvement, cost reduction and eventually growth in net profit (Fullerton, Kennedy & Widener, 2014). However, the failure of effective implementation of lean strategy is significantly more than those of success. This is perhaps because the traditional cost accounting system is not suitable for lean thinking and does not provide adequate, accurate, and timely information for an effective application of it (Gracanin et al., 2014).

Advanced Costing Systems

The literature discusses the significance of developing costing systems that fit with the lean thinking strategy since the traditional one is appropriate for mass production style rather than for lean production (Gracanin et al., 2014). Therefore, modern costing systems have been developed to overcome the limitations of this system. This study focuses on Throughput Accounting and value stream costing systems that are believed to be more suitable systems than others for the lean thinking strategy.

Throughput Accounting

Throughput Accounting (TA) is based on the operation concepts of Theory of Constraint (TOC). The TOC as Kirche & Srivastava (2005) point out is a systematic approach used to enhance a system’s performance through managing the flow of material and increasing the utilization of capacity at the bottleneck operation. The main goal is to enhance profitability measured by the contribution earned at the bottleneck (its throughput). The basic idea of TOC is that there is at least one constraint in every organization that refers to anything those barriers a system from achieving higher performance toward its goals (Sheu, Chen & Kovar, 2003). The TOC deals with scheduling production methods by an existing facility in a way that will achieve maximum profitability by the maximization of output. To achieve this, TOC depends on the system of pull-through production management. In this system, the movement of products into the production process or from one operation to another will be only if capacity becomes available to start working on it. Production capacity in this system is defined by the capacity of that part of the production process that works as a constraint on throughput (Fritzsch, 1998). As, Lockamy & Spencer (1998) argue, the main advantage of TOC is its ability to link the operational goals to the global objectives of an organization. For example, net profit, and cash flow will increase if throughput increases and inventory and operating expenses decreased. Conversely, net profit, and cash flow will decrease if throughput decreases and inventory and operating expenses increase. This is one of the limitations determined in the traditional cost accounting system that is a lack of performance measures that are used at an operational level and at the same time support the management on the global level. However, the TOC emphasizes the importance of including Throughput Accounting (TA) as an alternative approach to measuring the costs.

The concept of TA was proposed by management consultants David Galloway and David Waldron. Their proposal aims to remove some of the traditional ideas, including direct/indirect cost allocation, treating inventory as an asset and economic batch size. They emphasis that accounting should control the rate at which organizations make money. Thus, they focus on the return per product per bottleneck hour (Freeman, 2007). It is based on the new set of measures that connect local decisions and actions to the performance of the organization (Draman et al., 2002). In the use of TA, only the costs of direct material are associated with products. All other kinds of costs such as labor and indirect costs are seen as fixed costs that are not assigned to products. Therefore, all problems related to overhead allocations are overcome (Fritzsch, 1998). Whereas the focus of the traditional cost accounting system is upon product costs, the constraint-based accounting emphasis upon organization profitability by measuring Throughput (T), Inventory (I) and Operating Expenses (OE). Throughput refers to the money produced by the system through sales. As unsold products do not generate revenues, it focuses only on sold products instead of simply output. So, in the TA approaches, any unsold unit of products does not count as throughput. Also, Inventory refers to the money invested by the system in purchasing things for selling. In the TA the value-added prospect of inventory has been removed to overcome the process of generating unwanted inventory to show good results on paper. Thus, the inventory in the TA represents a liability that must be minimized. Finally, the operating expenses refer to all the money spending by the system to convert inventory into throughput. It includes direct labor, manufacturing overhead and selling and administrative costs. These items represent period expenses that are not allocated to products and should be covered by throughput see (Lockamy, 2003; Draman et al., 2002; Sheu, Chen & Kovar, 2003).

Thus, it can be said that the AT enables operational managers to evaluate more easily the influence of their decision on throughput, inventory levels, or operating expenses. These measures then can be used to explore the effect of operational performance on the financial performance on the global level of organization. According to Lutilsky, et al., (2018), the TA enables organizations to emphasis on bottom-line results, profit or loss, using the measurements of operation. The superior of AT is its predication on increasing throughput and how it accomplishes its aims. Scheduling and constraint are major barriers to increased throughput due to the fact that TA is not accepted under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), it is necessary to separate it from the official financial statements, and thus many organizations do not apply it. TA is a significant evolution in cost accounting that highlights the contribution of constrained resources to overall profitability. Applying TA would lead to enhance profit performance through better analytical decisions that would take into consideration three critical variables including throughput, inventory and operating expense (Freeman, 2007).

Value Stream Costing (VSC)

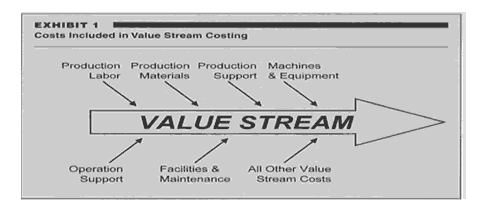

The traditional cost accounting system is conflicted with the lean thinking strategy that organizations intend to achieve. Thus, one of the costing alternatives approaches that have been developed to overcome the limitation of traditional cost accounting is Value Stream Costing (VSC). VSC traces the actual cost to the individual value stream. Instead of allocating the actual cost of organizations to products, services or departments, it is allocated to the value stream. The value stream costing comprises only those costs that are directly allocated to it. It is typically prepared weekly and there is no distinction between direct and overhead costs (Baggaley & Maskell, 2003). All the costs of each value stream are considered direct costs. It is applied to avoid the problems regarding the calculation of overhead cost, to simplify the costing system and to eliminate wasteful transactions. The average cost per unit calculated under value stream cost represents sales unit not production and that will avoid the incentive for overproduction (DeBusk, 2015). In fact, value stream cost is applied to trace the costs of material, labor (direct or indirect) and overhead to the individual value stream. For example, labor costs that allocate to the value stream involve all those who work in this value stream whether they make the product, maintain the machine or do the accounting. The cost of material and other support costs such as spear part is calculated similarly based on the amount purchased for value stream each week. However, the only attribution used within VSC is the cost of square footage or meters for the facility. This actually incentives the team member of the value stream to decrease the wide space used by the value stream (Baggaley & Maskell, 2003). It can be seen that the difference between direct and indirect costs within the value stream will disappear because all costs are considered direct, while the costs outside the value stream are not included (Gracanin et al., 2014). Thus, the financial information provided by VSC can be understood by all the staff across the value stream. This in turn would lead to improve decisions making, a catalyst for implementing lean improvements across the whole value stream and clear accountability for cost and profitability (Maskell & Kennedy, 2007).

The literature discusses that the VSC can be useful in lean thinking strategy. The use of VSC can play a substantial role in the success of implementing the lean thinking strategy as it provides understandable information for operational managers to make decisions that are consistent with lean objectives. Maynard (2007) identify four areas in which VSC support lean strategy. These areas include measure flow through the process; understanding the capacity of the process; providing financial information that is timely and relevant and supports strategic decision making and continuous improvement. Ozdemir (2017) argues that adopting VSC is a radical change from the traditional costing system and it enables organizations to focus on creating value for customers and providing better information for decision making. Lopez, et al., (2013) analyze the literature on VSC and found a growing interest in the topic. However, applying VSC and its research are still at an early stage. Maskell & Baggaley (2006) examine principles practices and tools framework of lean accounting and found that VSC is a cost management practice that supports lean transformation and continuous improvement projects. In another study by Baggaley & Maskell (2003) assert that standard costing does not support lean behavior and thus, it can be replaced by VSC in which decisions are made concerning the overall profitability of the value stream see figure 1.

Figure 1: Value Stream (Baggaley & Maskell, 2003)

Comparison between the value stream Costing and the throughput accounting

From the above discussion, it can be said that both approaches are considered advanced cost accounting systems that are fitted with the lean thinking strategy. They are similar, as Myrelid & Olhager (2015) determine, in terms of making a distinction between material costs and other costs and taking bottlenecks into account. However, they differ on some points. In terms of their tasks, the main task of TA is to increase throughput rather than cost-cutting, while cutting costs by increasing the flow rate is the main task of the VSC (Elsukova, 2015). Also, they are different in terms of their support to decision-makers. While TA covers short-term decisions, lean accounting focuses on both short to long term, with a stronger focus on medium to long term through its philosophy of continuous improvements. Another difference is related to the production organization. In Lean accounting, the production system is organized based on value streams, while there is no organizational change to the production system in throughput accounting (Myrelid & Olhager, 2015).

In terms of their drawbacks, both approaches have some shortcomings that influence their practical applicability. The accuracy of VSC depends on the maturity of applying lean thinking. Often, at the early stage of lean implementations, different kinds of waste are incurred such as transportations, defectiveness and inventories. This could influence activities that are difficult to transform into direct costs in the value stream (Bates, Filippini & Chiarini, 2012). Accordingly, the VSC involves an entirely lean organization that is organized around the value stream; it just provides a rough estimate of the product cost, and it is less accurate than other costing systems such as ABC as it avoids allocations. Another shortcoming is related to its methodology that considers all items of cost as equal and this work well only for short-term performance measurement, not the long term (Lopez et al., 2013). In addition, its implementation is not relevant to organizations in the early stage of lean thinking strategy. It is impossible, in practice, to find staff and machines completely dedicated to a single value stream (Chiarini, 2012). On the other hand, the shortcomings of TA that influence its applicability and effectiveness emerge from its inability to be used in long-term decisions making, and the assumption that operating costs are fixed, which is undesirable in many conditions (Lutilsky et al., 2018). Also, it needs to be applied to all functions within the supply chain including management, production, resources and support to be valid (Freeman, 2007).

Regarding their benefits, it can be said that VSC and AT have several benefits that encourage lean thinking organizations to applied them. The use of the VSC is a radical change from the traditional costing system and enables organizations to focus on creating value for customers and providing better information for decision making (Ozdemir, 2017). Comparing to traditional costing, the VSC also enables organizations to model their process on the shop floor and simplifies the accounting process. As an essential element in lean thinking strategy, the VSC inspire continuous improvement in operations and provide managers with relevant costing information (Myrelid & Olhager, 2015). According to Maskell & Katko (2013), VSC is more useful than the traditional costing system due to simple and valid information provided about cost control, internal decision making, and external financial reporting.. Its usefulness emerges from it involves very little work and provides reports that are immediately understandable to everyone and can be used throughout the organization. Also, the reporting system is simplified through decrease the number of transactions recorded and reported. The reports of accounting are easier to prepare, simpler to understand for shop floor staff and more effective for decision making (Fullerton, Kennedy & Widener, 2014).

The strengths of the AT, on the other hand, that makes it suitable for lean thinking strategy emerges from its simplicity and capability of generating weekly and even daily reports (Freeman, 2007). As discussed by Lockamy (2003), the benefits of TA are well documented in the literature. It is a simple cost accounting system that can help organizations to assess the influence of local decisions on the organizations’ goals and if it is followed when making production decisions, it can lead to the best short-term incremental profits (Lutilsky et al., 2018). It is a very useful approach applied within a large range of decisions of product mix and can result in accepted solutions, sometimes with little variations (Freeman, 2007). Its main benefit that fits with the lean thinking strategy is related to its focus on profit maximization by managing constraints, either a physical constraint or a policy constraint, which represent the most potential areas for improvement and enables organizations to guide their effort to eliminating waste. Thus, they can more easily avoid the problems incurred by placing too much priority on reducing operating expenses (Spector, 2006).

Conclusion

The research provides a theoretical analysis of advanced cost accounting systems that can support the achievement of the lean thinking strategy focusing on TA and VSC. The research argues that these systems are the most suitable ones for the lean thinking strategy. The superiority of these systems over others emerges from their focuses on improving flow through the process; managing constraints through the process; supporting continuous improvement projects; and providing appropriate information to promote lean thinking behavior and eliminate waste. These issues would help organizations to create value for customers which are the main goal of the lean thinking strategy.

The findings reveal that the adoption of these systems by organizations and the transition from the traditional cost accounting system is a radical change and require achieving “a maturity stage” of lean strategy. The research recommends using these advanced costing systems as a complement rather than a replacement for the traditional cost accounting system and on the project-by-project basis until achieving the maturity stage.

For future researches, empirical investigations are needed to validate the practical applicability of these systems in different sectors. In particular, there is a need for more about the prevalence of such systems among organizations around the world in comparison with the traditional costing system and for a better understanding of the difficulty and requirements of implementing these systems.

References

Albright, T., & Lam, M. (2006). Managerial accounting and continuous improvement initiatives: A retrospective and framework. Journal of Managerial Issues, 157-174.

Andrea, C. (2012). Lean production: Mistakes and limitations of accounting systems inside the SME sector. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 23(5), 681 – 700.

Myrelid, J.O. (2015). Applying modern accounting techniques in complex manufacturing. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 115(3), 402 – 418.

Baggaley, B. and Maskell, B.H., 2003. Value stream management for lean companies, Part II. Journal of Cost Management, 17(3), 24-30.

Baggaley, B., & Maskell, B.H. (2003). Value stream management for lean companies, Part II. Journal of Cost Management, 17(3), 24-30.

Bates, K., Filippini, R., & Chiarini, A. (2012). Lean production: Mistakes and limitations of accounting systems inside the SME sector. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 23(5).

Carnes, K., & Hedin, S. (2005). Accounting for lean manufacturing: Another missed opportunity? Management Accounting Quarterly, 7(1).

DeBusk, G.K. (2015). Use lean accounting to add value to the organization. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 26(4), 29-35.

Draman, R.H., Lockamy, A., & Cox, J.F. (2002). Constraint?based accounting and its impact on organizational performance: A simulation of four common business strategies. Integrated Manufacturing Systems.

Elsukova, T.V. (2015). Lean accounting and throughput accounting: An integrated approach. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3), 83-83.

Freeman, J. (2007). Theory of constraints and throughput accounting. Topic Gateway Series and Technical Information Service, 26.

Fritzsch, R.B. (1998). Activity-based costing and the theory of constraints: Using time horizons to resolve two alternative concepts of product cost. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 14(1), 83-90.

Fullerton, R., & Kennedy, F.A. (2009). Modeling a management accounting system for lean manufacturing firms.

Fullerton, R.R., Kennedy, F.A., & Widener, S.K. (2013). Management accounting and control practices in a lean manufacturing environment. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 38(1), 50-71.

Fullerton, R.R., Kennedy, F.A., & Widener, S.K. (2014). Lean manufacturing and firm performance: The incremental contribution of lean management accounting practices. Journal of Operations Management, 32(7-8), 414-428.

Gracanin, D., Buchmeister, B., & Lalic, B. (2014). Using cost-time profile for value stream optimization. Procedia Engineering, 69, 1225-1231.

Kennedy, F.A., & Widener, S.K. (2008). A control framework: Insights from evidence on lean accounting. Management Accounting Research, 19(4), 301-323.

Kirche, E., & Srivastava, R. (2005). An ABC-based cost model with inventory and order level costs: A comparison with TOC. International Journal of Production Research, 43(8), 1685-1710.

Kumar, A., & Nagpal, S. (2011). Strategic cost management–suggested framework for 21st Century. Journal of Business and Retail Management Research, 5(2), 118-130.

Lockamy III, A., & Spencer, M.S. (1998). Performance measurement in a theory of constraints environment. International Journal of Production Research, 36(8), 2045-2060.

Lockamy, A. (2003). A constraint?based framework for strategic cost management. Industrial Management & Data Systems.

Ivana, L., Liovi?, D., & Markovi?, M. (2018). Throughput accounting: Profit-focused cost accounting method. Interdisciplinary Management Research(IMR) 14, 1382-1395.

Maskell, B., & Katko, N. (2012). Value stream costing: The lean solution to standard costing complexity and waste. Lean accounting: Best practices for sustainable integration, 155-176.

Maskell, B.H., & Baggaley, B.L. (2006). Lean accounting: What's it all about? Target, 22(1), 35-43.

Maskell, B.H., & Kennedy, F.A. (2007). Why do we need lean accounting and how does it work? Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 18(3), 59-73.

Brian, H.M., & Baggaley, B.L. (2006). Lean accounting: What's it all about? Target, 22(1), 35-43.

Maynard, R. (2007). Count on Lean. BMA Inc, 28-33.

Ozdemir, Y. (2017). Profitability by selling below the average unit cost: Lean cost accounting and a real application. International Journal of Management Science, 4(4), 56-59.

Rahman, N.A.A., Sharif, S.M., & Esa, M.M. (2013). Lean manufacturing case study with Kanban system implementation. Procedia Economics and Finance, 7, 174-180.

Ramasamy, K.A. (2005). Comparative analysis of management accounting systems on lean implementation. "Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee.

Rosa, A.C.R., & Machado, M.J.C.V. (2013). Lean accounting: Accounting contribution for lean management philosophy. Tourism & Management Studies, 3, 886-895.

Ruiz?de?Arbulo?Lopez, P., Fortuny?Santos, J., & Cuatrecasas?Arbós, L. (2013). Lean manufacturing: Costing the value stream. Industrial Management & Data Systems.

Sheu, C., Chen, M.H., & Kovar, S. (2003). Integrating ABC and TOC for better manufacturing decision making. Integrated Manufacturing Systems.

Spector, R.E. (2006). Constraints management. Supply chain management review, 43.

Womack, J.P., & Jones, D.T. (2003). Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation.

Received: 25-Nov-2021, Manuscript No. aafsj-21-9484; Editor assigned: 27-Nov-2021; PreQC No. aafsj-21-9484(PQ); Reviewed: 14-Dec-2021, QC No. aafsj-21-9484; Revised: 20-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. aafsj-21-9484(R); Published: 25-Dec-2021