Research Article: 2019 Vol: 22 Issue: 5

Analysis of Factors Influencing Foreign Studies-Strategic Decisions-Results of a Hungarian Survey

Veronika Fenyves, University of Debrecen

Zoltán Bács, University of Debrecen

Barnabás Kovács, Institute for European Science Education and Research (IESER)

Tibor Tarnóczi, University of Debrecen

András Nemeslaki, Budapest University of Technology and Economics

Elvira Böcskei, Budapest University of Technology and Economics

Citation Information: Fenyves, V., Bács, Z., Kovács, B., Tarnóczi, T., Nemeslaki, A., & Böcskei, E. (2019). Analysis of factors influencing foreign studies–Strategic decisions–Results of a Hungarian survey. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 22(5).

Abstract

Higher education has a primary role in the competitive edge of the Hungarian economy. Therefore, it has been thought to be vital to map the motivation, the value transferring role and last but not least their effect on the national economy through the international students who study in Hungary. A high standard of education does not only serve the rise of a nation, but a cross border educational system can also provide a basis upon which research could be founded. This is why we are motivated to offer degree programmes to an increasing number of international students studying at our universities and to make international higher educational institutions available for Hungarian students. We sincerely entertain the hope that these international students will spread our good reputation in the world. Thus it is crucial to know and investigate with scientific methods their motivation and expectations. First, we need to learn how our educational system is regarded from the perspective of these foreigners, how much the structure of our education corresponds to international standards and what are its strengths and possible weaknesses. In the empirical part of our research, the motivation of full-time students who take part in a diploma course with the purpose of obtaining a diploma were analysed separately. Regarding the cases of the participants in full-time education, it has been examined which factors influenced the choice of country, namely Hungary as an educational target.

Keywords

Higher Education, Global Higher Education Competition, International Student Mobility, Full-Time Education, Multicultural Society, Social Relations, Career Opportunities, Cost-Benefit Principle

Introduction

Countries internationalize their higher education for many reasons. For instance, in the European Union cultural and economic reasons historically established by the ultimate objective of peace or high level policy to strengthen the European identification of younger generations. Contrary to this, in some other regions–e.g., in North-America–internationalization is rooted in the “melting pot” ideology, that is the outreach to younger generations to get familiar with a main home culture–such as the American–and familiarizing incoming students with local cultures and economical ideas. Some regions are net receivers of this growing international markets (especially countries with a presently or historically large global or colonial influence), some are exporters (the growing Asian and African countries) and some formulating their public policies regarding this new global industry. The impact of higher education goes way beyond the institutions of universities and ministries of education–competitiveness of regions, innovation potentials of countries and very importantly economic relations and long term trading policies might also be determined by how effectively a country builds up the internationalization policy of its higher education.

Hungary´s case is interesting for the following main reasons. Firstly, it is a Central European country with a unique language and national identity which is rather isolated. Although, there are about 1 million Hungarians living in diaspores of Romanian, Slovakian, Serbian, Croatian, Ukrainian or Austrian border regions or historically Hungarian towns and villages–Hungary´s population is decreasing and from the present 9.8 million inhabitants by 2050 close to 8 million is expected which indicates a drastic decrease for educational demand. Secondly, Hungary is one of the most open economies in the world with a high present of its GDP origination from foreign exchange which cannot be imagined without trade relations and competitive export-import activities. Thirdly, Hungary´s economy is highly dependent on knowledge intensive sectors such as IT, financial services, innovation and research centres and also vehicle industry.

We have initiated our research in order to draw conclusions from Hungary´s endeavours to in the last five years or so to initiate an effective internationalization of its higher education. Apart from showing a niche country case on this challenge, we formulated two main research questions:

1. What are the key factors which motivate students to choose a “niche” EU region such as Hungary for their studies?

2. Through what variables these factors can be influenced?

In order to answer these questions we designed an exploratory study surveying 3000 students study in Hungary. With these questions we have had both pragmatic intentions to support public policy and/or institutional strategy design for exporting Hungary´s higher education, and with that empirical investigation contribute also to theory in higher education development by basically building hypotheses how niche countries can improve their competiveness by attracting foreign students.

First a review on the state of the art and the general background. Then the research model, followed by the methodology. Discussion of results and their interpretation.

Finally, conclusions and implications.

Literature Review

Education and more precisely higher education is of utmost importance for every nation, therefore internationalization will eventually become a strategic factor. Globalization processes inevitably included and intensified internationalization. Numerous researchers have already drawn attention to the fact that globalization and internationalization are not the same concepts, even if it is obvious that globalization has a direct influence on higher education (Altbach & Teichler, 2001; de Haan, 2014). Internationalization comes into prominence both on the institutional and national level, therefore it is a question of how much it serves as an educational, political or economic objective (Svensson & Wihlborg, 2010). Within the knowledge-based society of the 21st century, universities must adapt to economic challenges as well. The question is how much pressure institutions are to be faced. In the globalized world, higher education is also a part of the market competition of political and economic forces; however, it is uncertain how much the academic sector is affected by its positive or negative impacts (Bartell, 2003).

Due to the declining tendency of public financing, the purely non-profit sector is constantly transforming, a mixed financing model is present, where profit is a priority. Consequently, the income-generating ability of international students became one of the determinant elements of internationalization. Thus, student mobility led to the emergence of the global higher education market (Wadhwa, 2016). By introducing fee-paying training, reduction or termination of missing resources might become achievable. This alone is not a necessarily negative factor if it is accompanied by high-quality education, if a high level of student services are ensured and research programmes are induced. However, concerns according to which positive effects of internationalization might be damaged in the case of higher education institutions with financial problems might be justified (De Vita & Case, 2003). Although earnings originating from tuition fees generate an income of billions of dollars or Euros (Altbach & Teichler, 2001), we believe that education will not and should not become a purely commercial category due to the traditions of the academic sector and the involved scientists.

Currently, globalized competition is present even in the case of higher education, where there is a competition for excellent students. When globalized higher education is discussed, it is interpreted as an economic category, just like in any other industrial sector–where open market competition is for the sales of services and products–with the difference, that provision of quality is continuously controlled and it must not fall below a certain level. International accreditation might provide a proper guarantee for this, so the fundamental question is whether the academic sector itself is able or is allowed to follow through this process consistently. Obviously, there will be (or there are) mainly smaller institutions which are able to temporarily recruit international students with lower quality services, however these institutions should not expect a long lifespan (Koryagina et al, 2018). In the course of this process, international accreditation will (or might) primarily have a key role, but secondarily, it is the labour market that evaluates graduates.

The fact that high-quality services provided by higher education must be paid for by students is not necessarily considered a negative factor if scholarship opportunities (among others) are provided for excellent students. Additionally, institutions and graduates are ranked by the labour market, by offering career opportunities for excellent students. Whether a competition situation is able to emerge on the market of higher education, and to what extent the market is self-regulatory are fundamental questions of knowledge-based society.

Researchers distinguish two major periods of international higher education: periods before and after the economic transformation. Transfer of knowledge provided by international educational exchange programmes and sharing the opportunity of lecturing, learning, and researching were the major characteristics of the period before the economic transformation, using exchange programmes for students and lecturers. Creation of the intercultural dimension or the multicultural environment in the context of the learning and researching process has already appeared during this early stage (Arum & Van de Water, 1992; Knight, 1994; Knight & De Wit, 1995; Rudzki, 1995). At the end of the 90s, (Van der Wende, 2012)–completing the above–mentions that international mobility created the flow of highly qualified workforce and learning abroad includes the possibility of signing on a working position in the host country. The main characteristic of the period following the economic transformation is that increased demand was formed from the side of the market towards students having international experience and studies. The appearance of multinational companies, although indirectly but significantly influenced internationalization, since they prefer to employ young people with international experience, who tend to undertake internships already during their studies. Therefore, students consider international studies as a certain pledge of their career. The market recognizes the international experience, thus mobility demand of students has also increased (Jones, 2010; Mehta et al., 2016). However, this process was also perceived (realized) by higher education institutions, and competition has started for not only domestic but also foreign students.

International mobility became important not only institutionally, but on the governmental level as well. Education as a market category and as a revenue-generating sector, which was primarily embodied in the tuition fees paid by students, has evolved into a large income-generating sector. While international student exchange programmes were previously based on international collaboration, globalization has created a global higher education competition amongst governments (Knight, 2014; Wadhwa, 2016). Education itself generates billions of dollars (educational costs, subsistence costs), so besides present leading educational exporters (USA, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand) the market is extending with additional new players. As sharply pointed out by Wadhwa (2016), the primary driving force of the changes occurred in higher education was economic globalization. In the light of this, he expressed concern about how much Humboldtian education, which considered knowledge, human values, ethical and cultural understanding as primary standards is present in our time and how much it can be preserved.

Internationalization becomes important in Europe as well, higher education has also transformed in Central-Eastern Europe. Exploitation of potentials within international mobility, development of knowledge, skills, intercultural and linguistic competences, preservation and transfer of common European values and European identity became strategic issues for Europe (Petri, 2017). In the scope of scholarship programmes (e.g., ERASMUS programme), the opportunity to study abroad opens for hundreds of thousands of students annually. These programmes offer part-time studies, students spend an academic semester in the host country.

Europe is not only open to students arriving from the narrowly defined European area, but also welcomes young people arriving from distant parts of the continent and other continents. Primarily through their training carried out in English and German, university degrees of European countries are also challenged within the global market competition. In the case of participants of full-time training (not the students involved in scholarship programmes), the income-generating ability of tuition fees paid by international students is a significant additional resource for the European area. In the course of our research, motivations of international students pursuing their studies in a small European country (Hungary) were examined. In the present article, the motivation of international students pursuing full-time studies with the aim of obtaining a degree were analysed. With regard to the length limitations of the article, only a sub-area of the research is presented: the factors based on which international students chose Hungary as the destination for their studies. We sought answers to questions concerning how much the geopolitical area and a secure, welcoming multicultural environment are determinant factors when making decisions related to foreign studies. In terms of choosing an institution, how important was the desire for knowledge and the existence of a high-quality academic background for young people? What role does the existence of international accreditation–which is also a sort of guarantee for quality education – have in choosing an institution, how well is it known for students?

Do they consider tuition fees and subsistence costs, namely the cost-benefit ratio of the future degree?

Economic and social relations have changed radically in the past decades. The main question in terms of international student mobility is what steps are being taken by countries with different historical backgrounds to accept students from distant continents in their higher education institutions? This is especially true for such post-communist Central and Eastern European countries, where four decades ago, national borders functioned as a sort of wall, not just for studying, but also for simple entry and exit even as a simple tourist. The question is whether these four decades have been enough to for them to make their higher education institutions international. Although the primary focus is on the quality of education, it is equally important to have social openness, to create a safe environment, and to provide high quality opportunities for cultural entertainment.

In the scope of our research, we analyzed the motivations of foreign students pursuing their studies in a Central Eastern European country, Hungary. The overall picture of Hungarian higher education is interesting because, although the countries sending most of the students are the immediate neighbour countries (Slovakia, Romania, Serbia and Ukraine), but at the same time the number of students from countries like Norway or Asian (China, Iran) and African (Nigeria) countries is dynamically rising (Source: Statistical database of the Educational Office, database obtained for research purposes 2013-2015).

Research Methodology

Our research model is based on a large volume empirical survey of more than 3000 students studying for full degree in several Hungarian universities. With the comprehensive and broad questions firstly the first research question is answered, and the motivational factors are determined. These are considered as the dependent variables of the “study abroad” model. Secondly, as part of the previous questionnaire independent variables have been also explored and formalized. This we describe in the methodology section.

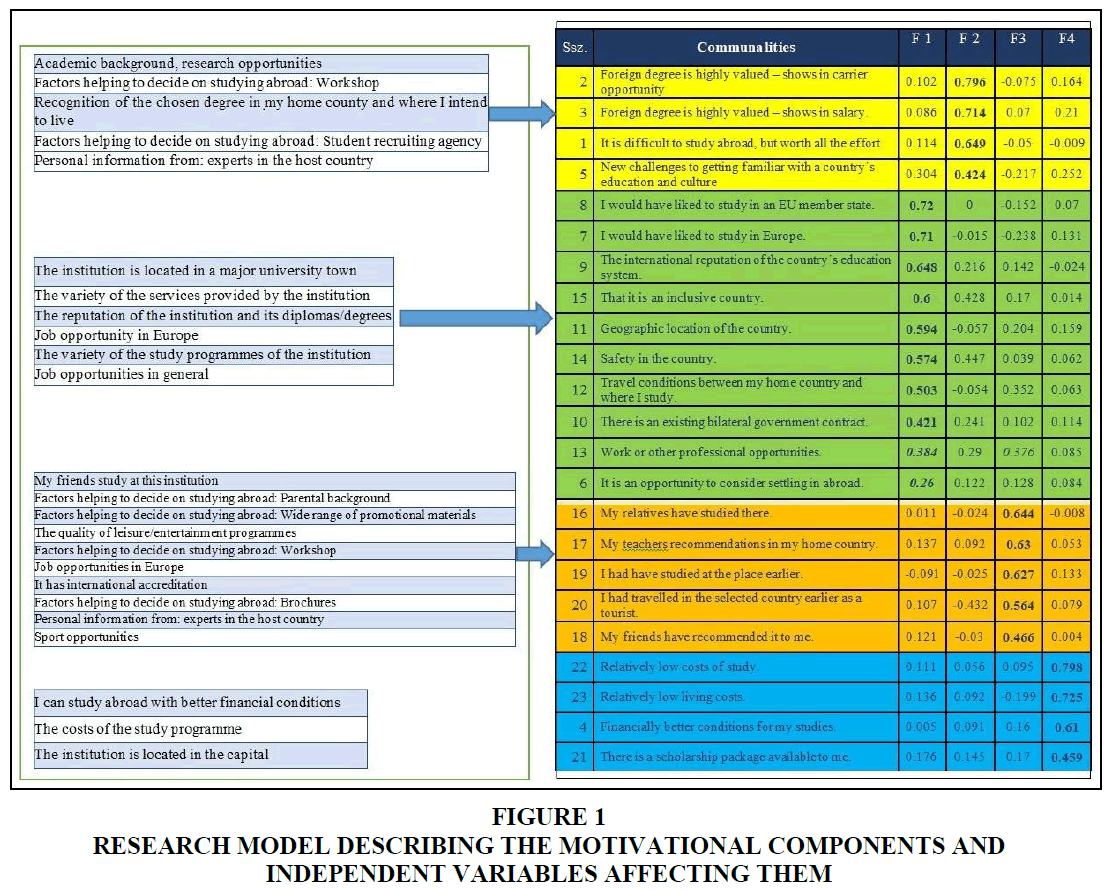

Two multivariate statistical computations have been designed to analyze the collected data. First, the dependent variables have been grouped, and key components have been identified with factor analysis. This is what is shown on the right side of Figure 1. Factor analysis has been basically the methodology to answer the first research question. Second, the factor components and the chosen independent variables have been analyzed with multiple linear regression to assess what variables impact the motivational components. This can be seem on the left side of Figure 1.

Figure 1 Research Model Describing the Motivational Components and Independent Variables Affecting Them

The left side–as dependent variables–describe those factors which determine students motivation to study in Hungary. Our assumption is, the more these motivational attributes are attained the more likely students will decide to move to Hungary and contribute to the internationalization of Hungarian education–consequently increase Hungary´s competiveness in the international higher education market.

Since the objective of our study goes beyond identifying motivations, and it aims to explore how motivations can be influenced–or taking a pragmatic point of view–what kind of actions could the Hungarian higher education policy envision in order to meet motivational expectations.

Methodology

For the exploratory study, a comprehensive questionnaire was designed to explore both sides of the research model.

Factor analysis was executed to identify the major motivational factors. We treated the factors as dependent variables, and ran multiple linear regressions by STRATEGICALLY selected independent variables.

In the case of students in full-time training, the questionnaire involved five subjects. Present article–concerning length limitations–covers the analysis of factors influencing foreign studies.

In the scope of this topic, the following areas were involved:

• Which factors influenced the students in studying abroad?

• Which factors supported their choice of studying abroad (internet, education exhibitions, brochures, personal information, parents, student recruitment agencies)?

• Which factors influenced the choice of the destination country?

• Which factors influenced the choice of the institution?

• Which factors dominated in terms of the available services of the institution?

• Which factors had a role in the choice of the training (course)?

• Satisfaction with the training language and the choice of the course.

• Satisfaction in terms of the institutional website, its informative nature.

Out of the international students pursuing studies in Hungary, a total of 3,042 people completed the questionnaire. Following the clearing of data, 86% of the returned questionnaires were processed, so 2,616 questionnaires were included in the sample, 1,165 of which referred to part-time training, and 1,451 to full-time training. The questionnaire was available in five languages, in English, German, Portuguese, Spanish and Hungarian.

Besides the questionnaire survey, in-depth interviews were performed with 215 international students. In the course of the in-depth interviews, eight topics were covered and the received responses outlined a number of opinions about education, integration, service portfolio, which confirmed the results of the questionnaire survey.

Considering the age distribution of foreign young people studying in Hungary, nearly 65% belong to the age group of 20-25 years. The proportion of students above 25 years is 30%, while the 18-20-year-olds amount only to 5%.

Analysing the number of students by continent, we found that most of them arrived from the “old” continent, Europe (46.3%), then from Asia (34.5%) and Africa (14.2%). The number of students from the American (4.7%) continent and Australia and Oceania (0.3%) is still relatively low.

Besides medical and health science (53.1%), most of the students who arrived from the European continent chose the area of humanities (13%). Students from the Asian continent prefer medical studies (39.4%), technology (21%) and economic (18.4%) training. Students from Africa chose medical studies (43%) technology (16.4%), agricultural (15.5%) and IT (15%) trainings. A student arriving from the American continent preferred medical studies (41.2%) technology (16.2%) and agricultural training (16.2%) besides economics (10.3%).

When analysing the influencing factors of studying abroad, we sought to answer the question, what the factors were based on which they decided to study abroad. The subjective value judgement of respondents appeared, when although nearly 60% (57.8%) felt that it is more difficult to study abroad, they still chose this form of further education. They indicated career opportunity as the reason behind this, which means they considered it a more important motivational factor than salary. International experience, international degree university years spent abroad–are appreciated in the world of labour, therefore its significance might be determinant in terms of their future career (62.3%).

Analysis of Results

Determining the Key Motivational Components with Factor Analysis: Dependent Variable of the Research Model

The Appendix shows the 23 questions assessed in a Likert-scale of 4 values collecting responses on the motivations for studying in Hungary. The value of KMO test was 0.789, with p<0,001 according to which partial correlation is not too high, thus the variables were suitable for factor analysis. The four resulting factor components of the analysis have been explaining 44% of the variance of our 23 variables which is not very high but we considered it satisfactory in our case. Components and the respective factor weights after the Varimax rotation are shown in Table 1.

| Table 1 Rotated Component Matrixa | |||||

| Ssz. | Communalities | FACTOR 1 | FACTOR 2 | FACTOR 3 | FACTOR 4 |

| Geography/ Country |

Iternational Degree | Social Recommendation | Costs | ||

| 2 | Foreign degree is highly valued–shows in carrier opportunity | 0.102 | 0.796 | -0.075 | 0.164 |

| 3 | Foreign degree is highly valued–shows in salary. | 0.086 | 0.714 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| 1 | It is difficult to study abroad, but worth all the effort | 0.114 | 0.649 | -0.05 | -0.009 |

| 5 | New challenges to getting familiar with a country´s education and culture | 0.304 | 0.424 | -0.217 | 0.252 |

| 8 | I would have liked to study in an EU member state. | 0.72 | 0 | -0.152 | 0.07 |

| 7 | I would have liked to study in Europe. | 0.71 | -0.015 | -0.238 | 0.131 |

| 9 | The international reputation of the country´s education system. | 0.648 | 0.216 | 0.142 | -0.024 |

| 15 | That it is an inclusive country. | 0.6 | 0.428 | 0.17 | 0.014 |

| 11 | Geographic location of the country. | 0.594 | -0.057 | 0.204 | 0.159 |

| 14 | Safety in the country. | 0.574 | 0.447 | 0.039 | 0.062 |

| 12 | Travel conditions between my home country and where I study. | 0.503 | -0,054 | 0.352 | 0.063 |

| 10 | There is an existing bilateral government contract. | 0.421 | 0.241 | 0.102 | 0.114 |

| 13 | Work or other professional opportunities. | 0.384 | 0.29 | 0.376 | 0.085 |

| 6 | It is an opportunity to consider settling in abroad. | 0.26 | 0.122 | 0.128 | 0.084 |

| 16 | My relatives have studied there. | 0.011 | -0.024 | 0.644 | -0.008 |

| 17 | My teacher’s recommendations in my home country. | 0.137 | 0.092 | 0.63 | 0.053 |

| 19 | I had have studied at the place earlier. | -0.091 | -0.025 | 0.627 | 0.133 |

| 20 | I had travelled in the selected country earlier as a tourist. | 0.107 | -0.432 | 0.564 | 0.079 |

| 18 | My friends have recommended it to me. | 0.121 | -0.03 | 0.466 | 0.004 |

| 22 | Relatively low costs of study. | 0.111 | 0.056 | 0.095 | 0.798 |

| 23 | Relatively low living costs. | 0.136 | 0.092 | -0.199 | 0.725 |

| 4 | Financially better conditions for my studies. | 0.005 | 0.091 | 0.16 | 0.61 |

| 21 | There is a scholarship package available to me. | 0.176 | 0.145 | 0.17 | 0.459 |

a: Rotation converged in 6 iterations.

Factor 1: Geopolitical Area, Country and Its Location: In the case of student motivational factors in this group, belonging and adapting to a multicultural social environment and being able to move within an unlimited, international space are dominant aspects. Values of the variables are high for respondents from whom it is important to study in a European country where education is internationally recognized. The geographic location of the host country is important for the respondents as is the quality of transport. It is also essential for them to study at a university in a welcoming, secure country.

Factor 2: International Career: Values of the variables are high in the case of respondents who think that their career will unfold through international studies or a degree obtained abroad. In their opinion, a foreign degree has a certain reputation. According to them, it is easier to obtain more beneficial job opportunities with international experience.

Factor 3: Social Relations and Recommendations: Factor 3 includes a group of students who were not necessarily motivated by multicultural environment and possible career when they decided to study abroad. In their case, the recommendations/suggestions of relatives, friends, parents, and teachers were the most determining factor for their choice. They focus on social relations, but they tend to risk less since they base their decisions on own experience–they have already studied in the given country or have been there as tourists–or on the opinion of their direct environment. The strong influence of friends is especially interesting; it appeared as a vital factor for 55% of the respondents.

Factor 4: Costs: In the case of students in full-time training (with the aim of obtaining a degree) scholarships and relatively low tuition and subsistence costs have a certain role in the choice of the country, but not as strikingly as in the scope of part-time training. Based on the responses, expectable subsistence costs represent a 50-50% weight in the decision-making of students.

Determining the Independent Variables to Influence Motivations: Independent Variables of the Research Model

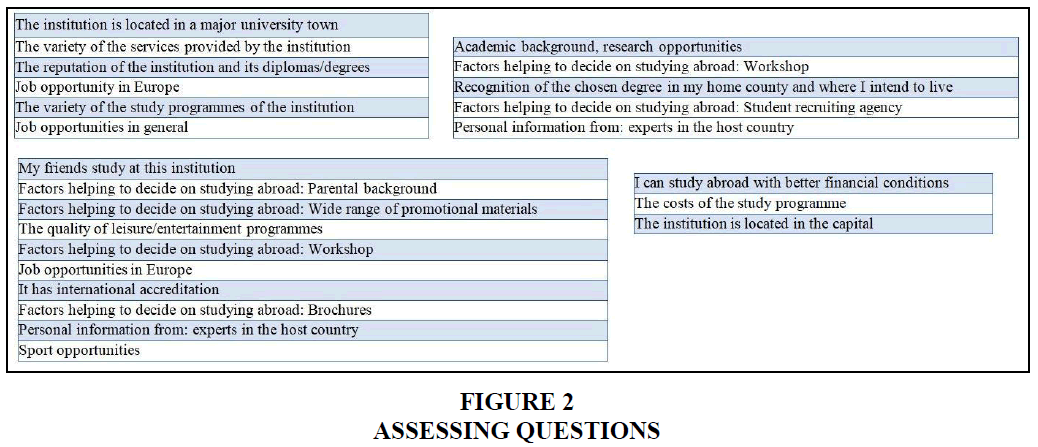

Four linear regression analyses were run in order to test the relationships between our motivational (dependent) and influence (independent) variables. These were run by assessing the following questions (Figure 2):

The results of the regression models are the following:

Linear Regression Model 1: Strategy of Becoming Familiar with the Geopolitical Area: A Multicultural Society

The regression model sought to answer the question, which factors influenced individual motivations, which factors had a role in the decision of students to pursue their studies abroad. How much the different variables affected the decision of respondents choosing the Strategy of becoming familiar with the geopolitical area–multicultural society.

The regression model was achieved in a single step. Value of Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r=0.419) can be read from the table summarizing the model (Table 2 and Table 3). The explanatory power of the value is 41.9%, (0.419a), while the value of the unbiased estimate belonging to the model is (R2) 0.175. The power of correlation is analysed using a coefficient of determination, this means that independent variables together explain 17% from the heterogeneity of dependent variables. The standard error of the estimate (SEE 89623700). Significance level of the F-test of the model (0.000) verifies the existence of correlation (Sig.<0.05), the regression model constitutes a significant part of the total heterogeneity.

| Table 2 Model Summary–Regression Model 1 | |||||

| Model Summaryb | |||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

| 1 | 0.419a | 0.175 | 0.170 | 0.89623700 | 1.958 |

b: Dependent Variable: REGR factor score1 for analysis 6

Source: SPSS processing of own database (based on completed questionnaires).

| Table 3 Coefficients–Regression Model 1 | |||||

| Coefficients | |||||

| Model 1 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | -1.294 | 0.095 | -13.552 | 0.000 | |

| The institution is located in a major university town | 0.134 | 0.028 | 0.151 | 4.783 | 0.000 |

| The variety of the services provided by the institution | 0.127 | 0.038 | 0.137 | 3.301 | 0.001 |

| The reputation of the institution and its diplomas/degrees | 0.125 | 0.041 | 0.101 | 3.019 | 0.003 |

| Job opportunity in Europe | 0.091 | 0.028 | 0.096 | 3.222 | 0.001 |

| The variety of the study programmes of the institution | 0.084 | 0.035 | 0.094 | 2.380 | 0.018 |

| Job opportunities | 0.089 | 0.031 | 0.092 | 2.854 | 0.004 |

Values of the significance levels of the t-test were below 0.05. Due to different variables, Standardized Beta coefficient was applied in the model. Based on the setup model, multicultural environment and the geopolitical area had a role in the decision of international students pursuing their studies in Hungary when they chose Hungary as their destination country. Students choosing this strategy considered a priority that the chosen higher education institution is located in a major university town (Beta 0.151) and the variety of services provided by the institution was also a determining factor in their decision (Beta 0.137). In the course of their further education, they considered the reputation of the institution and the value of its degrees (Beta 0.101), and that they will have job opportunities in Europe (Beta 0.096). Besides the services provided by the institution, the variety of offered study programmes also had a major role in the choice of the students (Beta 0.094) similarly to job opportunities after graduation (Beta 0.092).

Linear Regression Model 2: The Strategy of a Possible Career

The regression model sought to answer the question, how much different variables influence the decision of students preferring the strategy of a possible career. The correlation between a possible career and dependent variables is analysed.

The regression model was achieved in a single step. Value of Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r=0.513) can be read from the table summarizing the model (Table 4 and Table 5). The explanatory power of the value is 51.3%, (0.513a), while the value of the unbiased estimate belonging to the model is (R2) 0.263. The power of correlation is analysed using a coefficient of determination, this means that independent variables together explain 26% from the heterogeneity of dependent variables. The standard error of the estimate (SEE, 86134934).

| Table 4 Model Summary–Regression Model 2 | |||||

| Model Summaryb | |||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

| 2 | 0.513a | 0.263 | 0.260 | 0.86134934 | 1.749 |

b: Dependent Variable: REGR factor score 2 for analysis 1

Source: SPSS processing of own database (based on completed questionnaires)

| Table 5 Coefficients–Regression Model 2 | |||||

| Coefficients | |||||

| Model 2 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | -1.663 | 0.097 | -17.122 | 0.000 | |

| Academic background, research opportunities | 0.221 | 0.029 | 0.228 | 7.714 | 0.000 |

| Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Workshop | 0.177 | 0.027 | 0.200 | 6.639 | 0.000 |

| Recognition of the chosen degree in my home county and where I intend to live | 0.172 | 0.031 | 0.160 | 5.647 | 0.000 |

| Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Student recruiting agency | 0.097 | 0.026 | 0.105 | 3.707 | 0.000 |

| Personal information from: experts in the host country | 0.069 | 0.025 | 0.078 | 2.714 | 0.007 |

A significance level of the F-test of the model (0.000) verifies the existence of correlation (Sig.<0.05), the regression model constitutes a significant part of the total heterogeneity.

Based on the setup model, the possibility of a career had a role in the decision of international students pursuing their studies in Hungary when they chose Hungary as their destination country. Students choosing this strategy considered the existence of academic background and research opportunities a priority (Beta 0.228). Recognition of the chosen course in their home country and their intended residence in the future were important aspects (Beta 0.160) as well. Their decisions were highly supported by workshops (Beta 0.200), and the suggestions of agencies (Beta 0.105). However, information from experts of the host country also confirmed their decision (Beta 0.078).

Linear Regression Model 3: Strategy of Social Relations

The regression model sought to answer the question, how much different variables influence the decision of students preferring the strategy of social relations.

The correlation between social relations and dependent variables is analysed.

The regression model was achieved in a single step. Value of Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r=0.533) can be read from the table summarizing the model (Table 6 and Table 7). The explanatory power of the value is 53.3%, (0.533a), while the value of the unbiased estimate belonging to the model is (R2) 0.284.

| Table 6 Model Summary–Regression Model 3 | |||||

| Model Summaryb | |||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

| 3 | 0.533a | 0.284 | 0.277 | 0.85751 | 1.785 |

b: Dependent Variable: REGR factor score 3 for analysis 1

Source: SPSS processing of own database (based on completed questionnaires)

| Table 7 Coefficients–Regression Model 3 | |||||

| Coefficients | |||||

| Model 3 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta1 | |||

| (Constant) | -1.803 | 0.135 | -13.395 | 0.000 | |

| My friends study at this institution | 0.204 | 0.026 | 0.237 | 7.834 | 0.000 |

| Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Parental background | 0.177 | 0.025 | 0.207 | 7.011 | 0.000 |

| Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Wide range of promotional materials | 0.150 | 0.035 | 0.152 | 4.299 | 0.000 |

| The quality of leisure/entertainment programmes | 0.124 | 0.024 | 0.151 | 5.192 | 0.000 |

| Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Workshop | -0.123 | 0.031 | -0.139 | -3.926 | 0.000 |

| Job opportunities in Europe | -0.120 | 0.028 | -0.123 | -4.284 | 0.000 |

| It has international accreditation | -0.090 | 0.026 | -0.098 | -3.443 | 0.001 |

| Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Brochures | 0.095 | 0.034 | 0.097 | 2.794 | 0.005 |

| Personal information from: experts in the host country | 0.071 | 0.028 | 0.080 | 2.521 | 0.012 |

| Sport opportunities | 0.063 | 0.028 | 0.068 | 2.215 | 0.027 |

The power of correlation is analysed using a coefficient of determination, this means that independent variables together explain 28% from the heterogeneity of dependent variables—standard error of the estimate (SEE, 85751421).

Based on the setup model, social relations had a vital role in the decision of international students pursuing their studies in Hungary when they chose Hungary as their destination country. Students who chose this strategy handled as a priority that their friends already study in the chosen institution (Beta 0.237). Presumably, they also asked their friends to make inquiries concerning the courses. Amongst social relations, personal experience characterised students following this strategy. Confirmation of parents, the parental background also play essential roles (Beta 0.207). Their decisions are probably preceded by thorough research since besides the support of their friends and parents, they also read promotion materials (Beta 0.152) and they demand personal orientation from the experts of the host country (Beta 0.080). They look for “quality” social relations, which might be the starting point of a future career that is successful in the long term. Under certain circumstances they are open to the world, international accreditation, research (Beta 0.98) are important for them, but decent leisure time (Beta 0.151) and sport (Beta 0.068) are crucial as well, however with less weight.

Linear Regression Model 4: Strategy of the Cost-Benefit Principle

The regression model seeks to answer the question, how much the decisions of students representing the cost-benefit principle (students for whom the development of expenses spent on education and studying (and their returns) are a priority) are influenced by different variables.

The correlation between resources invested in education (studies) and dependent variables is analysed.

The regression model was achieved in a single step. Value of Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r=0.663) can be read from the table summarizing the model (Table 8 and Table 9). The explanatory power of the value is 66.3%, (0.663a), while the value of the unbiased estimate belonging to the model is (R2) 0.440.

| Table 8 Model Summary–Regression Model 4 | |||||

| Model Summaryb | |||||

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

| 4 | 0.663a | 0.44 | 0.438 | 0.74789379 | 1.918 |

b. Dependent Variable: REGR factor score 4 for analysis 1

Source: SPSS processing of own database (based on completed questionnaires)

| Table 9 Coefficients–Regression Model 4 | |||||

| Coefficients | |||||

| Model 3 | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | -2.018 | 0.079 | -25.527 | 0 | |

| I can study abroad with better financial conditions | 0.504 | 0.02 | 0.573 | 25.372 | 0 |

| The costs of the study programme; The institution is located in the capita | 0.235 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 11.545 | 0 |

| The institution is located in the capital | 0.047 | 0.018 | 0.06 | 2.66 | 0.008 |

The power of correlation is analysed using a coefficient of determination, this means that independent variables together explain 44% from the heterogeneity of dependent variables—standard error of the estimate (SEE, 74789379).

Based on the setup model, the returns of expenditures spent on their education had a vital role in the decision of international students when they chose Hungary as their destination country. Students who chose this strategy handled as a priority to be able to study with better financial conditions (Beta 0.573). Costs of the course also had a role in choosing a training (Beta 0.260). The geographic location of the higher education institution was a critical factor, the capital was preferred (Beta 0.60) to major university towns.

Conclusion

From amongst the three poles of international student mobility-the Pacific pole (United States, United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand); the Central European pole (Central and Western European countries) and the Iberian pole (France, Spain and Portugal)-we focused on a small country in Central Europe, Hungary. Many publications deal with the issue of international student mobility, exploring the factors that influence the decisions of students regarding obtaining a degree abroad2. Although the motivations vary from person to person, the individual dominance of the poles is decisive from the aspect of learning abroad (Börjesson, 2017).

One of the key questions of our research was the correlation between international studies and selection of the country, the strategy followed by students when they decide to study abroad.

As a result of our research, we have identified four strategic directions3:

1. Recognition of the advantages of the geopolitical area, the strategy of a multicultural society without borders.

2. The strategy of career opportunities.

3. The strategy of social relations.

4. The strategy of the cost-benefit principle.

The questionnaire survey confirmed that students who are committed to international studies primarily choose a continent (geopolitical area) and then choose a country and an institution. Students who chose to study in Hungary would also like to study primarily in Europe and (or) a Member State of the European Union, so they chose mainly the continent and then only the country and then the institution.

The economic policy of Europe and Hungary places great emphasis on opening towards oriental countries therefore they establish cooperation agreements with major multinational Asian companies. One of the multiplier effects of the intensification of European and Asian economic relations is the shift towards student mobility. The number of students coming from Asian countries is increasing year after year in European higher education institutions.

In the case of Hungary, the number of students coming from Asian countries has increased in parallel with the expansion of Asian economic relations, and currently China is one of the largest sending countries. In 2015, students from 156 countries arrived to Hungarian universities. Those coming from the top 20 countries4 accounted for more than 76 present of the total number of foreign students studying in Hungary.

In the decision of foreign students, a potential career appeared as an important aspect when Hungary was chosen as the target country for their studies. Amongst the students who chose this strategy, the existence of a firm academic background, provision of research opportunities and the recognition of the chosen training in their home country or future residence were crucial.

Our research findings confirmed that there is student demand for high-quality higher education, therefore concerns according to which positive effects of internationalization (De Vita & Case, 2003) might be damaged are proved irrelevant. In addition to the educational accreditation in their own country, Hungarian universities have also set the goal of acquiring international accreditation to overcome the doubts mentioned above. On the other hand, international accreditation is expected to contribute to a strengthened student confidence, which will provide the given country and institution with market benefits in long term.

Parental reinforcement and parental background also have a prominent role in the selection of a country and institution. Their decisions are supported by promotional materials, along with the support of their friends and parents and they require personal information from professionals in the host country as well. Parental reinforcement has a greater role in the selection of country within the same continent. However, in the case of people from a distant continent, the choice of country/institution is less conscious, they primarily choose a continent. In their case, they rely on promotional materials when choosing a country and the Internet also provides a source of information. They are the ones who map out the potential presence of companies originated from their home country in the given host country.

For the students who prefer the cost-benefit principle, financial returns of the training was an important aspect when they selected Hungary as the target country for their studies. The students who chose this strategy considered it a priority that they are able to study with more favourable financial conditions, therefore their decision was affected by the tuition fee and subsistence costs as well.

In summary, it can be established that belonging and adapting to a multicultural social environment and movement without borders in an international space has become a priority in the motivation of students. Economic (political) relations are playing an increasingly important role.

Further Potential Research Directions-revaluation of Personal Attitudes

Internationalization currently affects all nations, both as receiving and/or sending countries, therefore the issue of mobility has become more prominent (Ahmad, 2015; Ahmad & Hussain, 2017; Ahmad & Buchanan, 2017; Foster, 2014).

Due to the digitalisation of the information flow, student mobility has no limits anymore. Thus, understanding the educational offerings of each nation and exploring the opportunities is not a problem.

The same can be stated about linguistic factors, as while a few decades ago non-English speaking countries were disadvantaged, currently almost every country offers courses in English (Crystal, 2003)5.

According to our research findings, while the emphasis is on the quality of education, it is equally important to be socially open, to create a safe environment, and to provide cultured high-quality entertainment options.

A major question of the upcoming decades is how demographic trends will shape and reshape the current poles of international mobility, when geographical distances are already becoming less and less important.

The question is to what extent are Asian and African students open to Central European countries with demographic problems? Especially in light of the fact that the number of Chinese students studying abroad is growing dynamically from year to year and is projected to be close to 800,000 by 2025 (Luo, 2017)6.

Currently, we still talk about competition and economic benefits when a host country and/or a higher education institution receive students from different nations. However, internationalization must lay the foundations for a mutual cooperation that creates a WIN-WIN situation for both parties.

Beyond financial profits, international mobility must represent much greater values. Values that are not measurable in numbers such as:

• Openness and tolerance through knowledge of different cultures.

• Development of a critical mind-set.

• Development of skills.

We agree with numerous researchers that the choice of studying abroad is a very complex process and there are various factors that influence decision-making7.

However, in addition to these factors, it is equally important to examine micro-level mobility processes and the personal characteristics of students (Lee, 2014; Wilkins et al., 2012; Li & Bray, 2007; Ahmad & Hussain, 2017).

Thus, mapping the drivers behind student mobility will continue to open up various areas of research.

Limitation

From a methodological standpoint, we consider important to point out that foreign students studying in full-time trainings (with the aim of obtaining a degree) and in part-time trainings were analysed separately.

At the beginning of our research we assumed that these two groups of students arrive to Hungary with different motivations, therefore separate questionnaires were prepared for them.

In the case of students in full-time training, the questionnaire involved five subjects (the online questionnaire was available on the website of the Hungarian Rectors’ Conference):

• General information (Information on the higher education institution (HEI) in; Level of the study programme, Name and place of the study programme, etc.).

• Which factors played a role for the foreign students to study outside their home country (when did they decide to study abroad, information sources, factors influencing the choice of country, institution, etc.).

• How satisfied are they with the chosen training and the organisation of teaching, and what are their plans following the completion of the training.

• What preliminary information did they have about the tuition fee and subsistence costs, what were the sources of funding. How did the costs of subsistence change? Expected return on training and subsistence costs. Ratio of leisure time and studies, opportunities to spend leisure time.

• How satisfied are they with the institutional services (technical equipment, educational infrastructure of lecture rooms, library services, institutional programs, ALUMNI system).

Present article–with regard to length limitations–covers the analysis of factors influencing foreign studies.

Acknowledgement

The research has been realised with the support of the Pallas Athene Geopolitical Foundation (PAGEO). The authors wish to express their gratitude for the statistical database provided by the Educational Authority.

1In the case of the (negative) betas, their absolute values were analysed, their signs were disregarded

2International student mobility is a form of capital, which is materialised in economic capital once the graduates enter the labour market (Brooks & Waters, 2011; Leung, 2013).

3Identified six motivational factors–knowledge of the host country/institution; recognition of the degree; personal recommendations; costs; environment, climate, geographic distance, social connections–which had a role in the selection of the institution. The listed six motivational factors and the motivational factors of the identified four strategic directions identified that influence foreign learning is very similar, almost the same, with only slight differences, mainly related to the geopolitical position of the host country (Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002).

4Germany, Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, China, Iran, Ukraine, Nigeria, Norway, Turkey, Israel, USA, France, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, Brasil, Japan, Vietnam, South-Korea.

5In the case of Eastern European countries, Russia is in a special position, since following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russian as a world language has lost its significance. Russia primarily offers its trainings in its mother tongue, so foreign students also have to cope with Russian language difficulties. (Pukhova et al., 2017). Adaptation difficulties to the educational environment can also pose a serious challenge for students from different cultural backgrounds (Mikheeva et al., 2017).

6China will be one of the largest exporters of global higher education trade, and many researchers have examined the motivational factors that make overseas studies attractive (Fang & Wang, 2014; Zhou, 2015; Zhu, 2016, Yang et al., 2017.).

Among other things, they addressed the question of whether Chinese students' motivations differ from those of other nations, and whether there are differences in motivation across different levels of higher education (basic training, master, doctoral trainings). Research proves that the motivation of doctoral students is different from that of university students, so it is worth examining this student group separately. Doctoral students considered international experience to be important for their careers, emphasizing the recognition of the academic background and rank of the host country (Li & Qi. 2019).

7The push-pull model was originally developed to explain the factors influencing human migration (Lee, 1966). Motivational decisions related to international studies were called „Push” and „Pull” models by, depending on whether the domestic environment or the host country has a larger weight in the decision-making process. However, they emphasize that the combination of the two (push and pull) is the most decisive it is impossible to take exclusively one of them into consideration (McMahon, 1992; Mazzarol & Soutar, 2002; Marginson & Rhoades, 2002; Maringe & Carter, 2007; Eder et al., 2010, Wilkins & Huisman, 2015; Li & Bray, 2007; Lee, 2017).

Appendix 1

| Appendix 1 General Questionnaire For Determining Motivation For Studying In Hungary | ||

| Questions | Fully Agree (4)…Not Significant (1) | |

| 1 | It is difficult to study abroad, but worth all the effort | |

| 2 | Foreign degree is highly valued–shows in carrier opportunity | |

| 3 | Foreign degree is highly valued–shows in salary. | |

| 4 | Financially better conditions for my studies. | |

| 5 | New challenges to getting familiar with a country´s education and culture | |

| 6 | It is an opportunity to consider settling in abroad. | |

| 7 | I would have liked to study in Europe. | |

| 8 | I would have liked to study in an EU memberstate. | |

| 9 | The international reputiation of the country´s education system. | |

| 10 | There is an existing byletaral governement contract. | |

| 11 | Geographic location of the country. | |

| 12 | Travel conditions between my home country and where I study. | |

| 13 | Work or other professional opportunities. | |

| 14 | Safety in the country. | |

| 15 | That it is an inclusive country. | |

| 16 | My relatives have studied there. | |

| 17 | My teachers recommendations in my home country. | |

| 18 | My friends have recommended it to me. | |

| 19 | I had have studied at the place earlier. | |

| 20 | I had travelled in the selected country earlier as a tourist. | |

| 21 | There is a scholarship package available to me. | |

| 22 | Relatively low costs of study. | |

| 23 | Relatively low living costs. | |

Appendix 2

| Appendix 2 Dependent And Independent Variables | ||||

| Dependent Variable | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

| Independent Variables | The institution is located in a major university town The variety of the services provided by the institution The reputation of the institution and its diplomas/degrees Job opportunity in Europe The variety of the study programmes of the institution Job opportunities in general |

Academic background, research opportunities Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Workshop Recognition of the chosen degree in my home county and where I intend to live Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Student recruiting agency |

My friends study at this institution Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Parental background Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Wide range of promotional materials The quality of leisure/entertainment programmes Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Workshop Job opportunities in Europe It has international accreditation Factors helping to decide on studying abroad: Brochures Personal information from: experts in the host country Sport opportunities |

I can study abroad with better financial conditions The costs of the study programme The institution is located in the capital |

| (R2) 0.175.

The standard error of the estimate (SEE 89623700). Significance level of the F-test of the model (0.000) verifies the existence of correlation (Sig.<0.05), the regression model constitutes a significant part of the total heterogeneity. |

(R2) 0.263.

The standard error of the estimate (SEE, 86134934). A significance level of the F-test of the model (0.000) verifies the existence of correlation (Sig.<0.05), the regression model constitutes a significant part of the total heterogeneity. |

(R2) 0.284. Standard error of the estimate (SEE, 85751421). | (R2) 0.440. Standard error of the estimate (SEE, 74789379). | |

References

- Ahmad, S.Z. (2015). Evaluating student satisfaction of quality at international branch camliuses. Assessment &amli; Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(4), 488-507.

- Ahmad, S.Z., &amli; Buchanan, F.R. (2017). Motivation factors in students decision to study at international branch camliuses in Malaysia. Studies in Higher Education, 42(4), 651-668.

- Ahmad, S.Z., &amli; Hussain, M. (2017). An investigation of the factors determining student destination choice for higher education in the United Arab Emirates. Studies in Higher Education, 42(7), 1324-1343.

- Altbach, li.G., &amli; Teichler, U. (2001). Internationalization and exchanges in a globalized university. Journal of Studies in International Education, 5(1), 5-25.

- Arum, S., &amli; Van de Water, J. (1992). The need for a definition of international education in U.S. universities. In: Klasek, C. (Ed.). Bridges to the futures: Strategies for internationalizing higher education.

- Bartell, M. (2003). Internationalization of universities: A university culture-based framework. Higher education, 45(1), 43-70.

- Börjesson, M. (2017). The global sliace of international students in 2010. Journal of Ethnic and Migration studies, 43(8), 1256-1275.

- Brooks, R., &amli; Waters, J. (2011). Student mobilities, migration and the internationalization of higher education. Sliringer.

- Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language. Cambridge: Cambridge University liress.

- De Haan, H. (2014). Internationalization: interliretations among Dutch liractitioners. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(3), 241-260.

- De Vita, G., &amli; Case, li. (2003). Rethinking the internationalisation agenda in UK higher education. Journal of further and higher education, 27(4), 383-398.

- Eder, J., Smith, W.W., &amli; liitts, R.E. (2010). Exliloring factors influencing student study abroad destination choice. Journal of Teaching in Travel &amli; Tourism, 10(3), 232-250.

- Fang, W., &amli; Wang, S. (2014). Chinese students’ choice of transnational higher education in a globalized higher education market: A case study of W University. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(5), 475-494.

- Foster, M. (2014). Student destination choices in higher education: Exliloring attitudes of Brazilian students to study in the United Kingdom. Journal of Research in International Education, 13(2), 149-162.

- Jones, G. (2010). Managing student exliectations: The imliact of toli-uli tuition fees. liersliectives, 14(2), 44-48.

- Knight, J. (1994). Internationalization: Elements and Checklioints. CBIE Research No. 7. Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE).

- Knight, J. (2014), Changing landscalie of crossborder higher education. In: Trends in internationalization of higher education in India. 29-44.

- Knight, J., &amli; De Wit, H. (1995). Strategies for internationalisation of higher education: Historical and concelitual liersliectives. Strategies for internationalisation of higher education: A comliarative study of Australia, Canada, Eurolie and the United States of America, 5, 32.

- Koryagina, N., Bagreeva, E., &amli; Makhova, L. (2018). Higher education restructuration: entrelireneurshili goals and motivational strategies. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(2S).

- Lee, C.F. (2014). An investigation of factors determining the study abroad destination choice: A case study of Taiwan. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(4), 362-381.

- Lee, E.S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demogralihy, 3(1), 47-57.

- Lee, S.W. (2017). Circulating East to East: Understanding the liush–liull factors of Chinese students studying in Korea. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(2), 170-190.

- Leung, M.W. (2013). ‘Read ten thousand books, walk ten thousand miles’: geogralihical mobility and caliital accumulation among Chinese scholars. Transactions of the Institute of British Geogralihers, 38(2), 311-324.

- Li, F.S., &amli; Qi, H. (2019). An investigation of liush and liull motivations of Chinese tourism doctoral students studying overseas. Journal of Hosliitality, Leisure, Sliort &amli; Tourism Education, 24, 90-99.

- Li, M., &amli; Bray, M. (2007). Cross-border flows of students for higher education: liush–liull factors and motivations of mainland Chinese students in Hong Kong and Macau. Higher education, 53(6), 791-818.

- Luo, W. (2017). More Chinese students set to study overseas. Retrieved from httli://www.telegralih.co.uk/news/world/china-watch/society/more-students-to-study-overseas/

- Marginson, S., &amli; Rhoades, G. (2002). Beyond national states, markets, and systems of higher education: A glonacal agency heuristic. Higher education, 43(3), 281-309.

- Maringe, F., &amli; Carter, S. (2007). International students' motivations for studying in UK HE: Insights into the choice and decision making of African students. International Journal of Educational Management, 21(6), 459-475.

- Mazzarol, T., &amli; Soutar, G.N. (2002). “liush-liull” factors influencing international student destination choice. International Journal of Educational Management, 16(2), 82-90.

- McMahon, M.E. (1992). Higher education in a world market. Higher education, 24(4), 465-482.

- Mehta, A., Yoon, E., Kulkarni, N., &amli; Finch, D. (2016). An exliloratory study of entrelireneurshili education in multi-discililinary and multi-cultural environment. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 19(2), 120.

- Mikheeva, T., Shaliovalova, E., &amli; Antibas, I. (2017). lisycho-liedagogical Adalitation of Arabic-Slieaking Students to Education Conditions in Russian Universities. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 20(3), 1-4.

- lietri, B. (2017). The strategic imliortance of student mobility in the internationalization of higher education. 62-67.

- liukhova, A., Belyaeva, T., Tolkunova, S., Kurbatova, A., Bikteeva, L., &amli; Shimanskaya, O. (2017). Assessment of conditions for obtaining higher education by foreign students in regional institutions of higher education in Russia. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 20(3), 1-6.

- Rudzki, R.E. (1995). The alililication of a strategic management model to the internationalization of higher education institutions. Higher Education, 29(4), 421-441.

- Svensson, L., &amli; Wihlborg, M. (2010). Internationalising the content of higher education: the need for a curriculum liersliective. Higher Education, 60(6), 595-613.

- Van der Wende, M. (2012). The role of US higher education in the global e-learning market. Retrieved from httli://cshe.berkeley.edu/liublications/docs/ROli.Wendelialier1.02.lidf

- Wadhwa, R. (2016). New lihase of internationalization of higher education and institutional change. Higher Education for the Future, 3(2), 227-246.

- Wilkins, S., &amli; Huisman, J. (2015). Factors affecting university image formation among lirosliective higher education students: The case of international branch camliuses. Studies in Higher Education, 40(7), 1256-1272.

- Wilkins, S., Balakrishnan, M.S., &amli; Huisman, J. (2012). Student choice in higher education: Motivations for choosing to study at an international branch camlius. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(5), 413-433.

- Yang, Y., Volet, S., &amli; Mansfield, C. (2018). Motivations and influences in Chinese international doctoral students’ decision for STEM study abroad. Educational Studies, 44(3), 264-278.

- Zhou, J. (2015). International students’ motivation to liursue and comlilete a lih. D. in the US. Higher Education, 69(5), 719-733.

- Zhu, J. (2016). Review of literature on international Chinese students. In Chinese overseas students and intercultural learning environments (lili. 41-102). lialgrave Macmillan, London.