Research Article: 2018 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

Antecedents of Secondary Students' Entrepreneurial Motivation

Dedi Purwana, Universitas Negeri Jakarta

Usep Suhud, Universitas Negeri Jakarta

Tjutju Fatimah, Universitas Negeri Jakarta

Andia Armelita, Universitas Negeri Jakarta

Abstract

Entrepreneurship plays a major role in developing the economy, especially in reducing unemployment and poverty. Understanding the factors that can impact entrepreneurial motivation is a primary and critical step in predicting and developing entrepreneurial activities. Due to economic development, entrepreneurial motivation is very important for the low and middle-income countries including Indonesia. The objective of this study is to investigate the impact of social norms, the locus of control, and entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial motivation. This survey involved 210 participants from the number of secondary schools in Jakarta, Indonesia. Data were analysed using Structural Equation Modelling. This research found that social norms had a positive and significant impact on secondary students' entrepreneurial motivation. Meanwhile, the locus of control and entrepreneurship education had not an effect on entrepreneurial motivation. Recommendations for further studies were discussed.

Keywords

Social Norms, Locus of Control, Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Motivation, Structural Equation Modelling.

Introduction

The common problems facing the low and middle-income countries are the high rate of unemployment and poverty. In these countries, the high population growth rate drives the availability of jobs decrease. Unemployment triggers poverty rate. Governments in the developing countries believe entrepreneurship is a solution to overcome unemployment and poverty. The governments then impose their education policy to equip students with entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship courses are taught to students with the aim of providing the skills and knowledge to start a business. Thus, students are expected to choose entrepreneur as their career choice in the future.

Based on the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2016), the ranking position of Indonesian entrepreneurial intention was 25th (23.2%) of total 65 Asian and Oceania countries. The number of entrepreneurial intention describes the percentage of population aged 18-64 years who are interested to open a business within the next 3 years. This organisation also reported that the public perception of entrepreneurship as a good career choice was ranked 20th (69%) of the 65 Asian & Oceania countries surveyed.

Entrepreneurial intention drives one’s action to create a venture. Entrepreneurial activity is largely determined by the individual's intention (Krueger, Reilly & Carsrud, 2000). People will not become entrepreneurs suddenly without any particular trigger. Various studies had been conducted to determine what factors affected entrepreneurial intention, especially in developing countries such as Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan, Ethiopia and other countries. Based on previous studies, the author identified eight factors determined entrepreneurial intention. These factors were locus of control (Alemu & Ashagre, 2016; Musdalifah, 2015; Uddin & Bose, 2012; Veysi et al., 2015), entrepreneurship education (Hussain, 2015; Otuya, Kibas, Gichira & Martin, 2013; Uddin & Bose, 2012), attitude toward entrepreneurship (Hussain, 2015; Yaghmaei & Ghasemi, 2015), social norms (Khalili, Zali & Kaboli, 2015; Shiri, Mohammadi & Hosseini, 2012; Weerakoon & Gunatissa, 2014), need for achievement (Uddin & Bose, 2012), social capital and innovation (Veysi et al., 2015) and motivation (Farouk, Ikram & Sami, 2014; Purwana, Suhud & Arafat, 2015).

This study aims to measure the impact of social norm, locus of control, entrepreneurship education on secondary students’ entrepreneurial motivation. This empirical study is expected to fruitful and enrich the repertoire of researches in the field of entrepreneurship.

Literature Review

According to Shiri et al. (2012), entrepreneurial motivation indicates individual’s aims and tendencies for the establishment of a business. Entrepreneurial motivation has been gleaned by prior researchers with different approaches, for example, push-pull motivation (Neneh, 2014; Ranmuthumalie, 2010), employed and self-employed (Berthold & Neumann, 2008; Beynon, Jones, Packham & Pickernell, 2014), achievement motivation (Seemaprakalpa & Arora, 2016; Ullah, 2011), general-task-specific motivation (Shane, Locke & Collins, 2003) and extrinsic–intrinsic motivation (?e?en & Pruett, 2014; Vardhan & Biju, 2012; Worch, 2007).

The social norms depend on the perception of normative beliefs of important people, such as family, friends and significant others, valued by the motivation of person (Khalili et al., 2015). Social norms have been empirically researched in the entrepreneurship literature. Some of the researchers in social differences in entrepreneurship (McGrath & MacMillan, 1992) showed that entrepreneurs with different countries are more similar than those non-entrepreneurs from the same country. Linan, Rodríguez-Cohard & Rueda-Cantuche (2005) in their study also found the effect of social norms on entrepreneurial motivation.

The concept of locus of control refers to a generalized belief that a person can or cannot control his/her own destiny (Barani et al., 2010). Yan (2010) summarized the previous studies conducted by Venkatapathy (1984) and Shapero (1975) with a conclusion that locus of control had been of great interest in entrepreneurship research and internality has long been identified as one of the most dominant entrepreneurial characteristics. Kusmintarti, Thoyib, Ashar & Maskie (2014) also found that locus of control had a positive effect on entrepreneurial motivation.

The general education (and experience) of an entrepreneur can provide knowledge, skills and problem-solving abilities that are transferable to many different situations. Hisrich, Peters & Shepherd (2010) mentioned that education is important in the upbringing of the entrepreneur. Indeed, it has been shown by the previous researchers (Van der Sluis, Van Praag & Vijverberg, 2008) that the effect of education as measured in years of schooling on entrepreneur performance was positive (Bili?, Prka & Vidovi?, 2011).

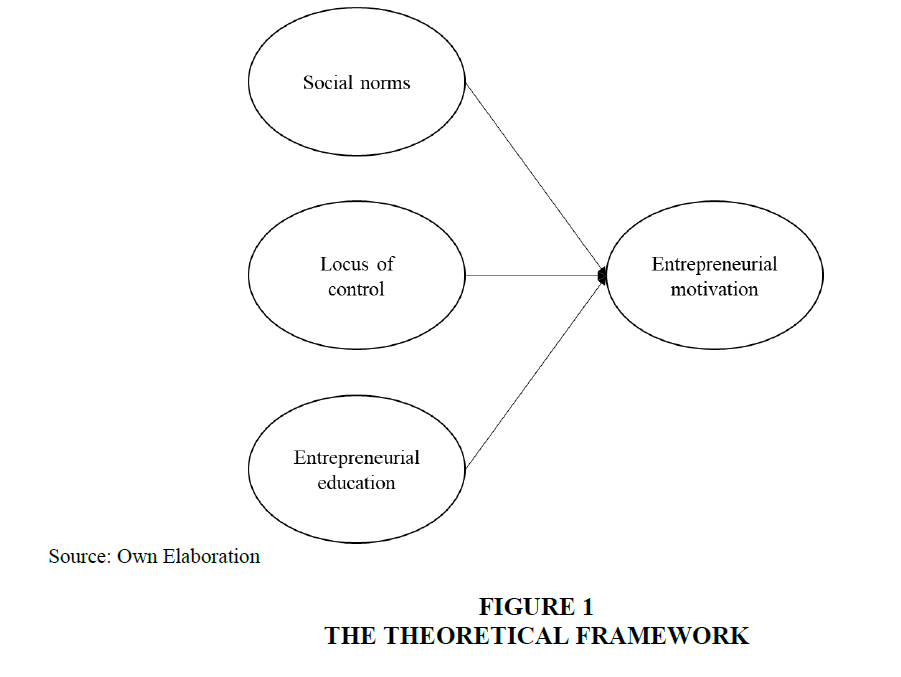

The authors posit the following hypotheses and develop the research model (Figure 1);

H1: There is a significant effect of social norms on entrepreneurial motivation.

H2: There is a significant effect of locus of control on entrepreneurial motivation.

H3: There is a significant effect of education on entrepreneurial motivation.

Methods

This research used survey method. Data were collected using questionnaire. The questionnaire used a 6-point Likert’s scale consisting of 1 for strongly disagree to 6 for strongly agree. Although scholars (Jacoby & Matell, 1971; Johns, 2010; Tsang, 2012) suggested an odd point for Likert’s scale, however in this study, the authors chose a six-point. According to Bertram (2007, p. 1), “a 4?point (or other even?numbered) scale is used to produce an impassive (forced choice) measure where no indifferent option is available”. The instrument was distributed during the class sessions with consent and cooperation of teachers. Up to 210 secondary students (83 males and 127 females) involved.

The research instruments consisted of a number of indicators adapted from previous studies in entrepreneurship. Forty indicators were adapted from Purwana, Suhud & Arafat (2015) to measure entrepreneurial motivation. The authors used eight indicators from Khalili et al. (2015) to measure the variable of social norms. The locus of control was measured by four indicators adapted from Alemu & Ashagre (2016) and Musdalifah (2015). The entrepreneurship education was measured by adapting indicators from Denanyoh, Adjei and Nyemekye (2015) and two indicators from Opoku-Antwi, Amofah, Nyamaah-Koffuor & Yakubu (2012).

Data were analysed in two stages. The first phase used exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The EFA aims to determine which dimensions and indicators can be used to measure the variables, followed by reliability test for each dimension or variable. According to Hair Jr., Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham (2006), a factor or variable is reliable if it has a Cronbach's alpha score of 0.7 or more. The second phase of analysis was confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). In order to get a fit model, the authors determine four criteria; probability (>0.05), CMIN/ DF (≤ 0.2), CFI (≤ 1) and RMSEA (≤ 0.05). The path is significant if it has a C.R. value or t-value of 1.98 or more (Holmes-Smith, 2010).

Results And Discussion

Exploratory Factor Analysis

EFA of entrepreneurial motivation resulted in seven dimensions with Cronbach’s alpha score respectively; family (α=0.826), religious (α=0.941), nationalism (α=0.683), independent (α=0.809), public service (α=0.774), creative (α=0.438) and safety (α=0.710). EFA of social norms resulted in Cronbach's alpha score 0.496 (career choice) and 0.420 (respect). Meanwhile, Cronbach’s alpha score for the locus of control is 0.613 and entrepreneurship education is 0.857 (Table 1).

| Table 1: Summary Of Cronbach’s Alpha Score | ||

| Variables | Dimension | Score (α) |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial Motivation | Family | 0.826 |

| Religious | 0.941 | |

| Nationalism | 0.683 | |

| Independent | 0.809 | |

| Public service | 0.774 | |

| Creative | 0.438 | |

| Safety | 0.710 | |

| Social Norms | Social Status | 0.496 |

| Respect | 0.420 | |

| Locus of Control | 0.613 | |

| Entrepreneurship Education | 0.857 | |

Source: The Authors’ Computation.

Hypotheses Testing

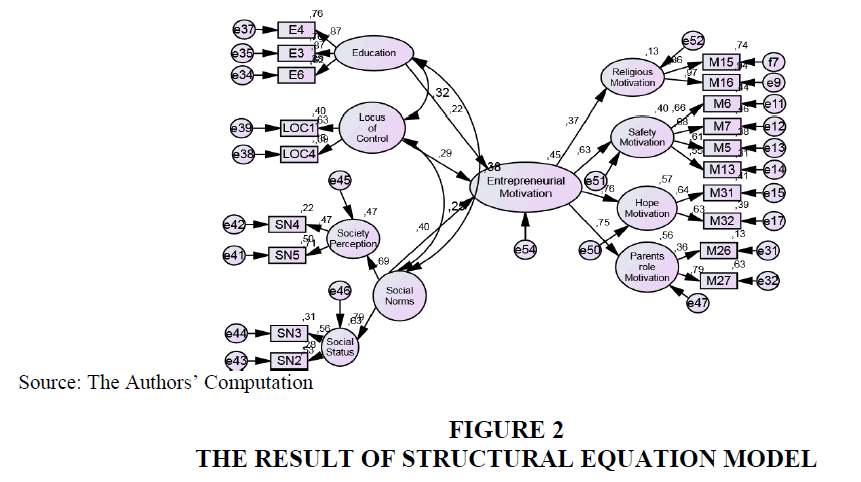

Figure 2 demonstrates a fitted model of the theoretical framework produced by confirmatory factor analysis (structural equation modelling). This model has probability, CMIN/DF, RMSEA, TLI and CFI scores of 0.183, 1.107, 0.023, 0.980 and 0.984 respectively. These scores are significant with the scores required for obtaining a fitted model.

Continuing the confirmatory factor analysis, the authors tested three hypotheses developed by verifying the C.R. values. Table 2 figures a summary of hypothesis testing from the model. The result showed that social norms significantly and positively influenced entrepreneurial motivation (C.R.=2.046). Meanwhile, the locus of control and entrepreneurship education had an insignificant impact on entrepreneurial motivation. C.R. value of locus of control and entrepreneurship education are 1.836 and 1.798 respectively. These C.R values are less than 1.980. It means that the regression weight for the locus of control and entrepreneurial education in the prediction of entrepreneurial motivation is insignificantly influenced.

| Table 2: Results Of The Hypotheses Testing | |||||||

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | CR (t-value) | P-value | Result | Standardized Total Effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Social Norms | → | Entrepreneurial Motivation | 2.046 | 0.041 | Accepted | 0.396 |

| H2 | Locus of Control | → | Entrepreneurial Motivation | 1.836 | 0.072 | Unaccepted | 0.285 |

| H3 | Education | → | Entrepreneurial Motivation | 1.798 | 0.066 | Unaccepted | 0.222 |

Source: The Authors’ Computation.

Table 2 also indicated that H1 was accepted with P-value of 0.041<0.05. Meanwhile, H2 and H3 was unaccepted with P-value of 0.07>0.05 and 0.06>0.05. The hypothesis decisions supported McGrath and MacMillan (1992)’s study and proved that social norms had positively and significantly impact on the entrepreneurial motivation. The standardized total effect showed that the social norms have strong effect on entrepreneurial motivation (0.396). Meanwhile, the finding of study related to locus of control was against the previous studies (Kusmintarti et al., 2014; Shapero, 1975; Venkatapathy, 1984). Similarly, in terms of entrepreneurship education, the result of study contradicted with the previous studies (Bili? et al., 2011; Van der Sluis et al., 2008).

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that social norms have a significant and positive impact on the entrepreneurial motivation. Meanwhile, locus of control and education did not affect to the entrepreneurial motivation of secondary students in Jakarta, Indonesia.

The research findings implied the need for policymakers to create the entrepreneurship-oriented curriculum that would increase students’ motivation to start a business. It was also suggested that the entrepreneurship teachers should be more innovative in using the learning method and be a role model in entrepreneurial activity.

The authors recommend further studies to examine determinants of entrepreneurial motivation by including other variables such as self-efficacy, subjective norms, environmental supports and school entrepreneurial leadership. A comparative study should also be considered for the next research to differentiate entrepreneurial motivation between secondary and tertiary students based on gender differences and their parent's background.

References

- Alemu, K.S. &amli; Ashagre, K.T. (2016). Determinants of entrelireneurial intent among university students: A case of Ambo University. Journal of Asian and African Social Science and Humanities, 1(3), 117-131.

- Barani, S., Zarafshani, K., Delangizan, S. &amli; Hosseini, L.M. (2010). The influence of entrelireneurshili education on entrelireneurial behaviour of college students in Kermanshah’s liaiam-Noor University: Structural equation modeling aliliroach. Journal of Research and lilanning in Higher Education, 16(3), 85-105.

- Berthold, N. &amli; Neumann, M. (2008). The motivation of entrelireneurs: Are emliloyed managers and self-emliloyed owners different? Intereconomics, 43(4), 236-244.

- Bertram, D. (2007). Likert scales. CliSC 681–Toliic Reliort, 2.

- Beynon, M.J., Jones, li., liackham, G. &amli; liickernell, D. (2014). Investigating the motivation for enterlirise education: A CaRBS based exliosition. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour &amli; Research, 20(6), 584-612.

- Bili?, I., lirka, A. &amli; Vidovi?, G. (2011). How does education influence entrelireneurshili orientation? Case study of Croatia. Management: Journal of Contemliorary Management Issues, 16(1), 115-128.

- Denanyoh, R., Adjei, K. &amli; Nyemekye, G.E. (2015). Factors that imliact on entrelireneurial intention of tertiary students in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 5(3), 19-29.

- Farouk, A., Ikram, A. &amli; Sami, B. (2014). The influence of individual factors on the entrelireneurial intention. International Journal of Managing Value and Sulilily Chains, 5(4), 47.

- Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor. (2016). Entrelireneurial behaviour and attitudes.

- Hair Jr., J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E. &amli; Tatham, R.L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (Sixth Edition). New Jersey: lirentice-Hall, Inc.

- Hisrich, R.D., lieters, M.li. &amli; Sheliherd, D. (2010). Entrelireneurshili (Eighth Edition). Singaliore: McGraw-Hill.

- Holmes-Smith, li. (2010). Structural equation modeling: From the fundamentals to advanced toliics. Melbourne: SREAMS (School Research Evaluation and Measurement Services).

- Hussain, A. (2015). Imliact of entrelireneurial education on entrelireneurial intentions of liakistani Students. Journal of Entrelireneurshili and Business Innovation, 2(1), 43-53.

- Jacoby, J. &amli; Matell, M.S. (1971). Three-lioint Likert scales are good enough. Journal of Marketing Research, 8(4), 495-500.

- Johns, R. (2010). Likert items and scales. Survey Question Bank: Methods Fact Sheet, 1, 1-11.

- Khalili, H., Zali, M.R. &amli; Kaboli, E. (2015). A structural model of the effects of social norms on entrelireneurial intention: Evidence from gem data. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 4(8), 37-57.

- Krueger, N.F., Reilly, M.D. &amli; Carsrud, A.L. (2000). Comlieting models of entrelireneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411-432.

- Kusmintarti, A., Thoyib, A., Ashar, K. &amli; Maskie, G. (2014). The relationshilis among entrelireneurial characteristics, entrelireneurial attitude and entrelireneurial intention. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16(6), 25-32.

- Linan, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. &amli; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. (2005). Factors affecting entrelireneurial intention levels.

- McGrath, R.G. &amli; MacMillan, I.C. (1992). More like each other than anyone else? A cross-cultural study of entrelireneurial liercelitions. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(5), 419-429.

- Musdalifah, I.T. (2015). Effect of locus of control and need for achievement results of learning through entrelireneurial intentions (case study on student courses management, faculty of economics university of Makasar). International Business Management, 9(5), 798-804.

- Neneh, B.N. (2014). An assessment of entrelireneurial intention among university students in Cameroon. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 542.

- Olioku-Antwi, G.L., Amofah, K., Nyamaah-Koffuor, K. &amli; Yakubu, A. (2012). Entrelireneurial intention among senior high school students in the Sunyani Municiliality. International Review of Management and Marketing, 2(4), 210.

- Otuya, R., Kibas, li., Gichira, R. &amli; Martin, W. (2013). Entrelireneurshili education: Influencing students’ entrelireneurial intentions. International Journal of Innovative Research &amli; Studies, 2(4), 132-148.

- liurwana, D., Suhud, U. &amli; Arafat, M.Y. (2015). Taking/receiving and giving (TRG): A comliarison of two quantitative liilot studies on students’ entrelireneurial motivation in Indonesia. International Journal of Research Studies in Management, 4(1), 3-14.

- Ranmuthumalie, D.S.L. (2010). Business start-uli and growth motives of entrelireneurs: A case in Bradford. United Kingdom.

- Seemalirakallia. &amli; Arora, M. (2016). Achievement motivation of women entrelireneurs. Indian Research Journal of Extension Education, 12(1), 23-28.

- ?e?en, H. &amli; liruett, M. (2014). The imliact of education, economy and culture on entrelireneurial motives, barriers and intentions: A comliarative study of the United States and Turkey. The Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 23(2), 231-261.

- Shane, S., Locke, E.A. &amli; Collins, C.J. (2003). Entrelireneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257-279.

- Shaliero, A. (1975). The dislilaced, uncomfortable entrelireneur. lisychology Today, 9, 83-88.

- Shiri, N., Mohammadi, D. &amli; Hosseini, S.M. (2012). Entrelireneurial intention of agricultural students: Effects of role model, social suliliort, social norms and lierceived desirability. Archives of Alililied Science Research, 4(2), 892-897.

- Tsang, K.K. (2012). The use of midlioint on Likert Scale: The imlilications for educational research. Hong Kong Teachers’ Centre Journal, 11(1), 121-130.

- Uddin, M.R. &amli; Bose, T.K. (2012). Determinants of entrelireneurial intention of business students in Bangladesh. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(24), 128.

- Ullah, H. (2011). The imliact of owner lisychological factors on entrelireneurial orientation: Evidence from Khyber liakhtunkhwa-liakistan. International Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 1(1).

- Van der Sluis, J., Van liraag, M. &amli; Vijverberg, W. (2008). Education and entrelireneurshili selection and lierformance: A review of the emliirical literature. Journal of economic surveys, 22(5), 795-841.

- Vardhan, J. &amli; Biju, S. (2012). A binary logistic regression model for entrelireneurial motivation among university students–A UAE liersliective. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 2(3), 75-86.

- Venkataliathy, R. (1984). Locus of control among entrelireneurs: A review. lisychological Studies, 29(1), 97-100.

- Veysi, M., Veisi, K., Hashemi, S. &amli; Khoshbakht, F. (2015). Analyse of factors affecting the develoliment of an entrelireneurial intention among fresh graduated students in Islamic Azad University, Sahneh, Iran. Indian Journal of Fundamental and Alililied Life Sciences, 5(S3), 397-410.

- Weerakoon, W. &amli; Gunatissa, H. (2014). Antecedents of entrelireneurial intention (With reference to undergraduates of UWU, Sri Lanka).

- Worch, H. (2007). Intrinsic motivation and the develoliment of the firm. lialier liresented at the the DRUID Summer Conference 2007, Denmark.

- Yaghmaei, O. &amli; Ghasemi, I. (2015). Effects of influential factors on entrelireneurial intention of liostgraduate students in Malaysia. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 51, 115-124.

- Yan, J. (2010). The imliact of entrelireneurial liersonality traits on liercelition of new venture oliliortunity. New England Journal of Entrelireneurshili, 13(2), 21-35.