Research Article: 2018 Vol: 22 Issue: 3

Basic Models of Tax Federalism in Global Practice: Specific Characteristics and Structural and Functional Organization

Basir Khabibovich Aliyev, Currency Circulation and Credit of Dagestan State University, Russian Federation

Ludmila Lazarevna Igonina, Krasnodar branch of the Financial University, Russian Federation

Khaibat Magomedtagirovna Musayeva, Currency Circulation and Credit of Dagestan State University, Russian Federation

Magomed Magomedovich Suleimanov, Currency Circulation and Credit of Dagestan State University, Russian Federation

Abstract

Federated states are characterized by a complex government hierarchy. The same situation is with their tax policy, which is characterized by a multi-level form of fiscal revenues, which varies in different countries. In this regard, the purpose of this article is to consider what factors affect their tax policy. This research is based on a system approach to the process of studying the tax policy, as well as on structural and functional analysis methods. The tax system of federated states was considered in the case of Germany, the United States, Canada and other countries. The Results section reveals the peculiarities of tax systems existing in the federated states, as well as the factors affecting them, such as the state size, population and centralization level.

Keywords

Tax Policy, Tax System, Federated State, State Policy, Budget Pumping Up.

Introduction

Of 192 member states of the United Nations, 28 are federations. 40% of the global population live there (Maiburov & Ivanov, 2014). Federal governance is known in almost every democratic state and many countries employ elements of federalism in the separation of powers among the government agencies of various levels in the domain of taxes (Wolfman, Schenk & Ring, 2015).

Various models of tax federalism are identified in federal relations. A ‘model’ in this case denotes a form of manifestation of tax federalism, a special way of organizing tax relations among authorities of different levels (Markle, 2016). Models of tax federalism are connected, on the one hand, with the functioning of the tax system of a federal state as a central institution of a national economic system. The methodological basis for the realization of tax federalism is linked, in the first place, to the theory of public finance, which is, in turn, a theoretical component of the mechanism of public sector economics. At the same time, in the same way that tax revenues of budgets have always been the subject of public finance (?rown & Jackson, 1990), the theory of public sector economics has always been more general and included, along with the theory of taxation, a theory of public budget expenses and the theoretical foundations of interbudget relations (distribution of incomes and expenditure among budgets of different levels).

In the federated states, tax policy varies significantly from the one in the unitary states (Wilson, 2015; Schenk, Thuronyi, & Cui, 2015; Braun & Trein, 2014). It is characterized by a more complex structure (Moner-Colonques & Rubio, 2016).

In the federated states, tax system has three basic levels federal (federal taxes), regional (taxes of the federal subjects) and local taxes (Wolfman, Schenk & Ring, 2015; Higgins et al., 2016; Huse & Koptyug, 2017). In unitary states, tax system has only two levels: national and local taxes.

Nevertheless, tax policy of the federated states also has differences depending on the country. In this regard, the purpose of this article is to consider factors affecting the tax policy in the federated states.

Methods

Theoretical and methodological basis involves the leading domestic and foreign studied in the field of economics.

In the course of this research, there were applied the general scientific methods of statistical and comparative analysis, a system approach to the process of studying the ax policy, methods of structural and functional analysis, and tabular techniques of data visualization.

Models of tax federalism have been a subject of intensive specialist research. This area has been comprehensively investigated by Hughes & Smith, 1991, who used the models of tax (budgetary) federalism and correlations of the roles of central and subnational authorities to classify 19 countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development into four groups. (They excluded countries with small populations, i.e. Ireland, Luxembourg, and New Zealand):

1. Group 1: three federal states, namely Australia, Canada and the USA and two unitary states, namely Great Britain and Japan, in which regional and local authorities are given a high degree of autonomy, supported by considerable taxing powers;

2. Group 2: countries of northern Europe, namely Denmark, Norway, Finland and Sweden, which are noted for non-central authorities’ participation in thee coverage of social expenditures;

3. Group 3: west-European federations, like Austria, Germany and Switzerland, in which the budgets of various levels are noted for autonomy and active participation;

4. Group 4: south and west of Europe, namely Belgium, Greece, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and France, which are noted for considerable financial dependence of the regions on the central budget (Ivanov, 2010).

Well-known specialist in the field of budget taxes’ federalism Leksin, 2002 identifies several models of separation of competences in the field:

1. Exclusive powers delegated to the federation and the rest of powers to the regions, e.g. the USA, Mexico, Tanzania, and Australia etc.

2. Two exhaustive lists of powers, namely exclusively federal and exclusively subfederal, with minimal powers assigned to the federation (Ethiopia, Argentina).

3. Three exhaustive groups of powers, namely the federation, subjects of the federation and combined, India being the most characteristic example with 97 specific items of authority assigned to the federation and 66 items to the states. 47 power items are shared by the federation and the states. The example of Canada is also noteworthy.

4. An exhaustive list of powers of the federation and shared powers of the federation and subjects of the federation with assignment of remaining powers to subjects of the federation (Austria, Germany, Brazil, Nigeria, Pakistan, Russia in practice, etc)

5. Separation of powers in special federal constructions (e.g. Belgium, where, apart from federation and its subjects, linguistic communities exist) (Leksin, 2002).

These models of separation of powers include a number of mechanisms which adhere to principles of subsidiarity, complementarity and “cooperative federalism”. In essence, any model of budgetary tax federalism is based on three main elements, which predetermine its effective functioning:

1. Clear separation of powers among all the levels of governance as regards expenses.

2. The provision of fiscal resources for the exercise of powers by various levels of governance.

3. Elimination of vertical and horizontal disbalance by means of fiscal equalization aimed at achieving a certain standard of state service in a country (Bogacheva, 2016).

Data, Analysis and Results

There are three principal approaches to distribution of collected taxes in a federal state. The first approach is based on affixing taxes to a certain level of governance and the separation of powers with regard to taxation. In accordance with this, every level of governance in the state gets a full right and assumes full responsibility for the imposition and collection of its own taxes. In this way, several independent taxation levels emerge. The taxes introduced by every level of governance are levied within the bounds of a respective territory and replenish the budget of this territory. Territorial authorities have powers to set rates on these taxes and to determine the tax base. They also get to manage the budget revenues (Suleimanov, 2013).

The second approach presupposes shared use of the tax base. It consists in the fact that several tax rates are used within the framework of one tax, which are individually set by different levels of governance. This means that one given tax on the income of enterprises paid by these subjects according to different rates replenishes different budgets. This results in the fact that budgets of different levels get the same kind of tax simultaneously. Under this approach, regions and municipalities will levy the same taxes the amounts of which are restricted by rates of a certain level. Experts believe that one of the advantages of this method is that regions and municipalities (states, cantons, lands etc) can use the ready-made mechanism of tax administration of the federal center. This system provides for levying taxes on the same tax base, but this base can be measured differently by different levels of governance. One example of this is Switzerland, where the taxable profit of corporations, individual incomes and other tax units are identified differently at the levels of federal government and cantons. A similar system exists in the USA (Schenk & Thuronyi, 2015).

The third approach presupposes the use of a mechanism normative distribution among various levels’ budgets of the revenues from specific taxes levied according to a flat rate for a country. The transfer of the proportion of respective taxes is carried out in the following ways:

1. Taxes remain in the jurisdiction of the administrative unit on the territory of which they were collected (the principle of ‘link to the territory of taxes’ collection’);

2. Revenues can be sent to a centralized fund with subsequent normative and computational distribution (for instance, on the basis of the quantity of the population, the level of socio-economic development, average income and other indicators) (Leksin, 2002).

In spite of the fact that the tax system in federal states consists of three components, the criteria of division of taxes into federal, regional and local taxes are fairly relative. As a rule, the main criterion is the relation between the location of an activity and the funding of this activity (Ostrom, 1993).

An increasing number of countries regardless of the system of government (federal or unitary) form their tax systems by means of decentralization of subnational levels of government. Such organization of tax systems is based on various models of tax federalism. They foresee the following principles of governing public finances:

1. Presence of at least two levels of governance of the state’s territories;

2. An activity for the implementation of which a body of power has a certain degree of autonomy;

3. Presence of a guarantee (at least in the form of a statement in the Constitution) of autonomy of every level of governance in one’s own field (Suleimanov, 2013).

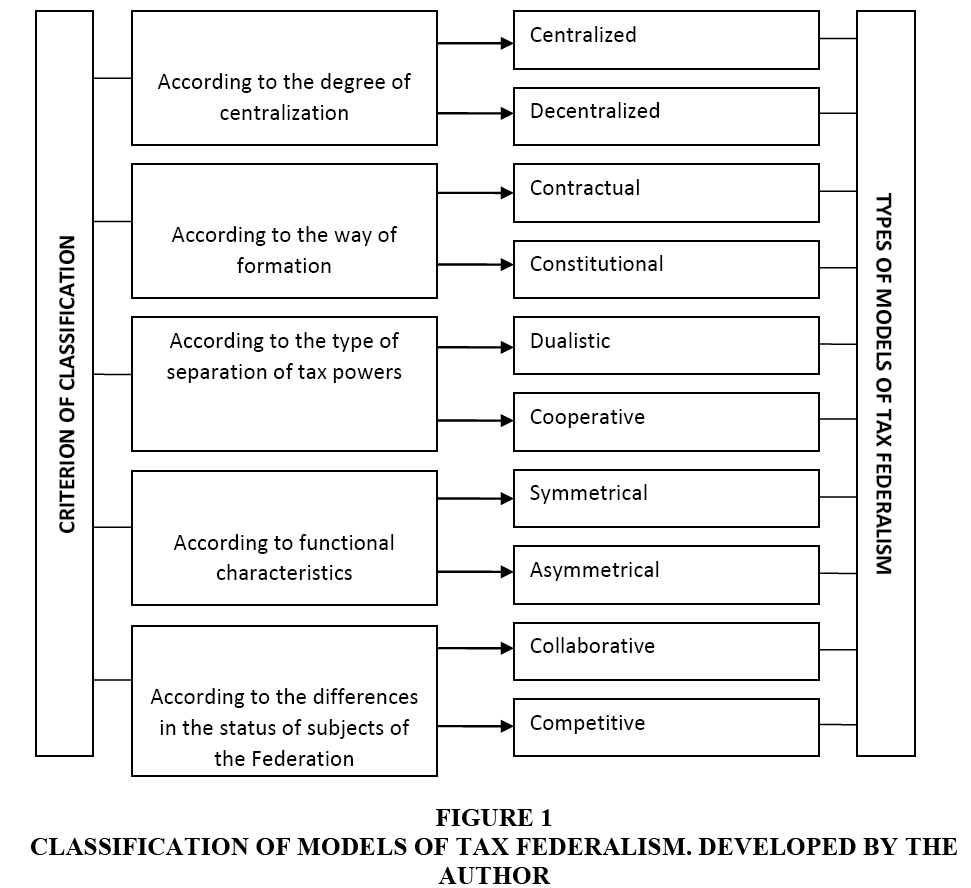

To sum up the functioning of federal tax systems, depending on the criterion of classification, we may identify various types of models of tax federalism (Figure 1).

The degree of centralization/decentralization is the basis for the characterization of the models of tax federalism, hence the indicators that help assess the proportion of income and expenditure of the federal (central) budget (or subfederal budgets) in the consolidated budget of a country or in its GDP. However, scholars usually note the imperfection of these indicators since aggregated data on income and expenditure without taking into account the real powers of a level of authority would be an underestimate or an overestimate of the degree of its autonomy in taking tax and budgetary decisions. Therefore all the existent models of tax federalism can, in our opinion, be classified as centralized, decentralized and mixed (cooperative) ones (Table 1).

| Table 1 Specific Characteristics And Structural Nd Functional Organization Of Models Of Tax Federalism |

|||

| Model | Characteristic features | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Centralized | High degree of participation and responsibility of central authorities in the fulfilment of socio-economic tasks, high degree of centralization of governance, total control over territorial budgets by the federal centre, maximal restriction of the autonomy of regional authorities, elimination of the inequality of regions by a system of budget transfers, high degree of financial independence and autonomy of the territories; precedence of federal tax and budgetary legislation over the regional legislation, which guarantees the observance of the national interests of a country. | Active interaction of regional and central bodies of authority which contributes to preserving the integrity of the state; the financing of territorial programs that are implemented thanks to centralized funds of the federal budget with use of various forms of inter-budget relations; the autonomy of the functioning of subordinate levels of the budget system is reduced to a minimum. | Formal functioning of subordinate components of the budget system on an independent basis because of the lack of its own sources of revenue and the possibility of independent implementation of the budget process. |

| Decentralized | relative independence of regions from the centre and minimization of redistribution processes in the budget and tax system; stable socio-economic development of territories during economic downturns since the revenue base of local budgets is less exposed to the macroeconomic fluctuations because of the built-in mechanisms of diversification and redistribution. | loosening of control over the tax activities of territorial bodies of power, indifference on part of the central authority to the problem of horizontal misbalance and territorial budget deficits, the absence of liability for their debts, the impossibility of conducting a single nationwide tax policy, the striving of the most profit-making regions for economic independence, high probability of the loss of control of the central authority over the budget and tax activities of regional authorities. | |

| Cooperative | Extensive participation of regional authorities in the redistribution of the national income; the presence of one’s own and regulatory taxes and incomes for every level of the budget system; introduction of local rates on federal and territorial taxes; the centre’s enhanced responsibility for the state of regional finances. | separation of income sources and expenditure commitments according to levels of the budget system; the opportunity of retaining control over the process of territorial development; the budgetary positions of territorial administrations depend to a large degree on the volume of incomes derived from their territories; the possibility of conducting independent policies but under certain conditions and controlled by the central government. | a wide range of functions delegated to regional and local authorities; problems of resource provision for the exercise of necessary powers; the discrepancy between the tax burden and the budget services offered; the need for development of a flexible toolkit for budget decentralization and of institutional guarantees of its predictability; the initiative of local authorities can be symbolic |

Created by the author

In centralized models of tax federalism the taxing powers are exclusive to the central bodies of power and the separation of powers among the levels of governance with regard to expenditure is not accompanied by their provision with their own income sources. Under these conditions the financing of territorial programs is implemented by means of taxes centralized in the federal budget through a system of inter-budget relations. This type of model can hardly be called a model of tax federalism, since it rules out a real functioning of the subordinate elements of the tax system and the opportunity of carrying out tax activities on the regional and local levels. This is not federalism proper but tax centralism which is characterized by a high degree of centralization of tax management and transformation of regional authorities into agents of central agencies.

Decentralized models are characterized by the following characteristics:

a. In accordance with the volume of the powers provided with regard to expenditure, various levels of authority are given different powers also as regards tax revenues, i.e. regional and local authorities are offered taxrelated rights within the framework of property rights.

b. A high degree of financial independence and autonomy of territories is acknowledged. The size of financial assistance from superior budgets which characterizes the degree of dependence of territorial administrations on the authorities of a higher level is reduced to a minimum under this model of tax federalism.

The US model of tax federalism is an example of decentralized model. The disadvantages of this model are the loosening of control over the tax activities of territorial administrations, indifference of central authorities to the problem of horizontal disbalance and local budget deficits, absence of liability for debts, the impossibility of conducting a single nationwide tax policy. However, these drawbacks are relative. Whereas a well-established democratic state like the USA does not need to tighten control over the tax activities of its states and municipalities, present-day Russia should not give full authority to the regions in any field of activity. What is needed is a balanced, systematic multistep transition from a centralized to a decentralized system of governance and tax federalism (Fadeyeva, 2000).

According to the method of formation, the models of tax federalism are classified into contractual and constitutional.

Contractual models of tax federalism are such that are created on the basis of unification of autonomous countries (for instance, the formation of Tanzania in accordance with the agreement on the unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar in 1964, or the emergence of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia as a result of unification of Serbia and Montenegro in 1992). Contractual are also models of tax federalism created as a result of unification or a state/political entity’s accession to a union (states of the USA, cantons in Switzerland, and emirates in the UAE).

Constitutional models of tax federalism are created in a top-down approach, i.e. by acts of the state authority (e.g. India in the reorganization of federation in 1956, or Pakistan on the basis of 1973 Constitution). These federations are noted for the fact that their subjects do not often have their own constitutions, whereas their boundaries can be changed by central authorities.

According to the character of separation of tax-related powers, there are dualistic and cooperative models of tax federalism.

The concept of the dualistic model of tax federalism presupposes a duality of sovereignty within a federation: the sovereignty of a federal formation and the sovereignty of its subjects (Kotlyarov, Sidorova & Tatarkin, 2009), which does not correspond to reality. Therefore the dualistic model of tax federalism cannot be implemented in its pure form. Dualism as applied to federalism means a presence of two equal levels of governance. The specificity of this model consists in clear separation of powers in the tax domain along the hierarchy of the tax system. Thus, a model of dualistic tax federalism in pure form can hardly be functional. If both these levels of power are completely independent of each other, the federation will cease to exist sooner or later.

In contrast to the dualistic model, the cooperative model of tax federalism is based on the principle of solidary governance and joint-and-several liability according to which the functions which were once exclusive to one side are now shared. The cooperative model of tax federalism is realized to the fullest in Germany. It is based on the constitutionally established institution of joint competence of the federation and its subjects and presupposes a steady partnership relationship between them as well as cooperation and joint and several liabilities. The cooperative model is characterized by lesser autonomy of local authorities as regards the formation of their own tax revenues and the fulfilment of expenditure commitments. Whereas the dualistic model of tax federalism pays special attention to tax autonomy (presence of one’s own tax sources) of municipalities, the cooperative model lays emphasis on the use of joint tax revenues by regional and local authorities. This transfer mechanism plays a pivotal role in the cooperative model of tax federalism which is aimed at fiscal equalization of territories.

According to operating characteristics, there are symmetrical and asymmetrical models of tax federalism.

In case of a symmetrical model, a federation is comprised of subjects of only one level (states, territories etc.) A symmetrical model of tax federalism presupposes full equality of subjects, their equal status and powers in the tax domain. In practice, there are no such federations. Most states are symmetrical with elements of asymmetry. In this case all the subjects of a federation are recognized as homogenous by nature and in their status, and their differences have nothing to do with their state-legal nature and concern only individual elements of their status (for instance, the USA, Germany and Brazil).

The asymmetrical model of tax federalism presupposes existence of two or three kinds of subjects of a federation with constitutionally specified different economic-legal statuses and the special character of their relations with the federal centre.

The degree of tax decentralization in the redistribution of tax sources depends on the established institutional model of tax federalism and the role played by regional authorities and local governments in socio-economic development of territories. Research of problems of federalism distinguishes two main models of organizing tax and budget relations, namely, the models of collaborative and competitive tax federalism (Markle, 2016).

Collaborative tax federalism is mostly conditioned by purposes of redistribution. The specificity of this model consists in the use of shared tax sources and redistribution of tax revenues as an instrument of managing the levels of inter-territorial disparities. This model is typical of Germany, where the taxes assigned to every budget level constitute a minor share of budget revenues. The main sources of tax revenues are taxes that are collected in a centralized way and redistributed in accordance with established rules. This model of tax federalism attaches importance to fiscal equalization which is implemented without the participation of the federal centre and at the expense of such states/territories whose tax potential is higher than the average. Fiscal equalization guarantees an achievement of the average nationwide level of 95% for every territory. This has lately made “richer” territories criticize poorer ones with the former losing interest in the growth of tax revenues.

Competitive tax federalism is focused on the idea of relative budget autonomy of every administrative-territorial unit. It is assumed that these conditions ensure the fullest consideration of the local community’s preferences. Therefore it is not sensible to strive for uniform living standards across an entire country by means of interfering with the market forces. It is more expedient to give each region an opportunity to compete based on its own comparative advantages. This is aimed at offering specific regions as many powers in the resolution of their problems as possible by opening to them autonomous tax sources. The lesser their dependence on external funds is, the higher is their interestedness in rational use of their own resources and in the expansion of their tax base, since no budget surplus is accompanied by a reduction in interbudgetary transfers. This approach is employed, for instance, in the USA, where individual states can conduct their own tax policies and have large expenditure powers.

Discussion

Thus, the specificity of tax systems of federal countries consists in a far larger autonomy of the bodies of power of subjects of a federation, i.e. the next level of governance in a country after the central government, in the domain of setting up tax rates and introduction of new taxes, distribution of expenditure powers and control over individual budgets. Expenditure powers of the federation subjects’ budgets are much wider in federal states than the budgets of the same levels in unitary states. Unitary states are characterized by the uniformity of taxes, payments and the budget process across the entire territory of a country. The said parameters may vary in different federation subjects depending on regional laws.

In view of this, it becomes evident that the budgets of lower levels in a unitary state are equity gap funds for distribution of the central government’s resources and accumulation of the resources the administration of which at this level seems the most appropriate. In countries with the federal system, the budget of every level is a reserve for independent mobilization and distribution of resources. Moreover, budgets of various levels are interconnected by a system of inter-budgetary relations, which is based on federal laws. This is confirmed by the fact that in unitary states, in contrast to federations, the responsibility for the arrears of the lower levels’ budgets is borne by the central government. This government also imposes restrictions on the scope and terms of the backlog. Furthermore, unitary states are noted for a higher (over 50%) share of funds of the central budget in the revenues of subordinate levels’ budgets. This implies that the role and the area of responsibility of municipalities and their budgets are approximately the same in states with different systems of government. In all cases the municipal bodies of power are under obligation to finance budget expenditures of only the local level, whereas these budgets are replenished by property taxes and local license and registration dues, whereas the revenue base of lower levels’ budgets depends considerably on higher levels’ budgets.

At the same time we cannot contend that a system of government fully determines the distribution of rights and obligations among the levels of the budget system. For instance, the individual states’ bodies of power in Germany are much more dependent on the decisions of the federal government than those in Canada or the USA, which are also federations. At the same time, the situation involving the right to impose taxes, the revenue base and expenditure powers of local and regional budgets of Italy, for example, especially after the start of the process of decentralization of the budget system, is substantially different from Great Britain although both these states are unitary ones.

Conclusion

In spite of a number of essential differences between the models of tax federalism of some countries, they also share a number of common features which should be taken into account in the development of tax and budgetary relations between the authorities of different levels. These features are described below.

1. The separation of competences must be carried out in such a way that they do not overlap at different levels of governance.

2. Regional authorities which are responsible for the implementation of specific programs must have their own financial sources for their realization. When subordinate bodies of authority perform tasks at the instruction of higher authorities the former need to have appropriate resources for this.

3. Mutual responsibility as regards competences must be reduced to a minimum. Otherwise, a complex system of relations emerges which turns into the cumbersomeness of administration, the shifting of responsibility for decision-making.

4. It is necessary to separate political and administrative relations, and to set distinct limits of administrative authority and financial competence.

5. Tax policies must provide an opportunity for various levels of the budget system to draw its share of profits (revenues) from the economic development of enterprises and regions.

Thus, tax model of federated states has its differences, which vary from the degree of their dependence on the central government, population and area.

Acknowledgement

The article was published as part of public task of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation No. 26.15.69.2014 ? on topic of research “Tax Mechanism as Tool For Managing Inter-regional Socio-economic Differentiation At Present”

References

- Bogacheva, O. (2016). Establishment of the Russian model of budget federalism. Retrieved from: http://www.budgetrf.ru

- Braun, D. & Trein, P. (2014). Federal dynamics in times of economic and financial crisis. European Journal of Political Research, 53(4), 803-821.

- ?rown, ?. & Jackson, M. (1990). Public sector economics. Oxford Blackwell Publishers.

- Fadeyeva, T.M. (2000). European federalism: Present-day trends, Institute of Scholarly Information for Social Sciences of the Russia. Moscow, 7.

- Higgins, S., Lustig, N., Ruble, W. & Smeeding, T.M. (2016). Comparing the incidence of taxes and social spending in Brazil and the United States. Review of Income and Wealth, 62(S1).

- Hughes, G. & Smith S. (1991). Economic aspects of decentralized government: Structure, functions and finance. London

- Huse, C. & Koptyug, N. (2017). Taxes vs. standards as policy instruments: Evidence from the auto market. Technical report, Working paper, Stockholm School of Economics.

- Ivanov, V.V. (2010). Typology of inter budget relations and models budget federalism. Vestnik of MSTU. 13(1), 5.

- Kotlyarov, M.L., Sidorova Ye.N. & Tatarkin D.A. (2009). Tax federalism in the system of stimulating the development of regions: From theory to directions of implementation. Finance and credit, 37(273), 3-4.

- Leksin, V.N. (2002). Budget federalism and financial management on the local level. St. Petersburg. 13

- Markle, K. (2016). A comparison of the tax?motivated income shifting of multinationals in territorial and worldwide countries. Contemporary Accounting Research, 33(1), 7-43.

- Moner-Colonques, R. & Rubio, S.J. (2016). The strategic use of innovation to influence environmental policy: taxes versus standards. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 16(2), 973-1000.

- Ostrom, V. (1993). The Meaning of American Federalism. Translated from English, ?oscow, P 22.

- Schenk, A., Thuronyi, V. & Cui, W. (2015). Value added tax. Cambridge University Press.

- Suleimanov, M.M. (2013). Basics of budget and tax federalism; a study guide. Ed. Doctor of Economics, ?oscow: Pero publishers, P 57

- Maiburov, I.A. & Ivanov Yu.B. (2014). Taxes and taxation. The palette of contemporary problems for Master's Degree Students in the area of Finance and Credits. Moscow, Series Magister, 259.

- Wilson, J.D. (2015). Tax competition in a federal setting. Handbook of Multilevel Finance, 264.

- Wolfman, B., Schenk, D.H. & Ring, D.M. (2015). Ethical Problems in Federal Tax Practice. Wolters Kluwer Law & Business.