Research Article: 2017 Vol: 23 Issue: 2

Can Social Entrepreneurs Do Well by Doing Good? Blending Social and Economic Value Creation - An Investigation

Keywords

For-Profit Social Entrepreneurial Ventures, Triple Bottom Lines, Profitability, Impact Measurement.

Introduction

For-profit social entrepreneurial ventures or ?SEVs? are those ventures that blend social goals with business goals and referred as ?double bottom lines organisations? or ?bottom of the pyramid ventures?. They pursue their goals differently compared to their commercial counterparts viz, entrepreneurial ventures or ?EVs?, whose primary aim is to create more economic value (Dees & Anderson, 2003; Dorado, 2006; Prahalad, 2006; Chell, 2007). SEVs for-profit are often posed as an answer to many of the pressing world problems. The combination of strong social purpose and an entrepreneurial drive to create a profitable business tend to deliver genuine results in inclusive growth.

But, does it make sense to blend the profit motive with a social objective? Earlier researchers like Adam Smith were quite sceptical about blending social good with economic benefits. The studies show that, the risks of conflict between pursuing profits and serving a social objective are significant. Successful examples that blend both social and economic value creation is very rare. (Dees & Anderson, 2003; Thompson & MacMillan, 2010). There are fewer numbers of entrepreneurs starting a social enterprise compared to commercial ones. The lack of awareness, perceived high risk, lower financial returns, etc. may push them away from starting a for-profit social enterprise. There are hardly any studies, empirical or conceptual; to enlighten these refuted fears about social entrepreneurship (Zahra, 2014; Short et al., 2009).

Further, there are hardly any studies comparing commercial and social entrepreneurship to exactly understand the similarities or differences in the process and impact creation (Braunerhjelm et al., 2012; Dorado, 2006; Shaw & Carter 2007). The emergent social entrepreneurship research has primarily utilised case studies or anecdotal evidence as a means to assess the phenomena of social venture creation (Mair & Marti, 2006) and systemized data collection efforts are lacking is limited empirical and quantitative research, rigorous hypothesis testing is lacking; little variety in research design is applied and the research is based on very small sample sizes (Braunerhjelm et al., 2012; Hoogendoorn et al., 2010). This trend is mainly due to the inherent difficulty and lack of widely accepted process or means to assess the value created by these social ventures (Dees, 1998).

Purpose of this article is thus, to close the research gap on the following unanswered questions in the existing literature.

? Can social entrepreneurs whose products and services are targeted to people at the bottom of the pyramid create profitable businesses?

? If so, what make their ventures profitable at the same time create the desired social impact?

? Can SEVs align wealth creation while serving a social purpose and do it well?

? Do they lag behind business entrepreneurs in creating profitable ventures?

This paper answers these questions through an empirical study. The data for this study are collected from the founders of practising social enterprises (for-profit) and commercial entrepreneurs from India.

Sevs and Evs: Converge or Diverge in Mission and Process?

The purpose of the literature review is to explore the possible similarities and differences between the nature and organisational characteristics of commercial and social ventures (SEVs and EVs) which may lead to differences in their performances.

Social enterprise involves a business like innovative approach to the mission of delivering community services. While the primary purpose of social entrepreneurs is to serve society, a social business has products, services, customers, markets, expenses and revenues like a regular enterprise. It is no-loss, no-dividend, a self-sustaining company, which repays its owners investments (Yunus et al., 2010).

Though there is a near unanimity regarding the primacy of social objectives, different individuals and agencies differ in their views about how they achieve these objectives. The literature based on conceptual studies says social enterprises can be viewed as a range of business practices that proactively build economic and social capital across the affected stakeholder groups. These enterprises are the development of alternate business practices and structures that support socially rational objectives (Ridley-Duff, 2008). Social enterprise is maximising revenue generation from programs by applying principles from for-profits business without neglecting core mission (Pomerantz, 2003).

Venkataraman studying traditional entrepreneurship sees the creation of social wealth as a by-product of economic value created by entrepreneurs (Venkataraman, 1997). In Social entrepreneurship, by contrast, social value creation appears to be the primary objective, while economic value creation is often a by-product that allows the organisation to achieve sustainability and self-sufficiency. In fact, for social entrepreneurship, economic value creation, in the sense of being able to capture part of the created value in financial terms, is often limited, and mainly because the customers may be willing but are often unable to pay for even a small part of the products and services provided (Seelos & Mair, 2005).

The societal benefits of providing appropriate products to lower-income and disadvantaged consumers can be profound, while the profits for companies can be substantial, says Porter et.al (Porter & Kramer, 2011). For a company, the starting point for creating this kind of shared value is to identify all the societal needs, benefits, and harms that are or could be embodied in the firm?s products. Meeting needs in underserved markets often requires redesigned products or different distribution methods.

Profits involving a social purpose represent a higher form of capitalism one that will enable society to advance more rapidly while allowing companies to grow even more. The result is a positive cycle of company and community prosperity, which leads to profits that endure (Porter & Kramer, 2011). Porter calls them as next evolution in capitalism.

Performance and Impact Measurement Practices in SEVs and EVs

The performance of an enterprise can be measured financially or operationally, subjectively or objectively. Most of the companies use multiple measurement indicators like efficiency, growth, profit, liquidity, market share etc. along with various subjective measures (Murphy, Trailer & Hill, 1996). Traditionally, entrepreneurial outcomes have been measured based on financial performance and firm survival (Ucbasaran, Westhead & Wright, 2001).

In a commercial setting, the main systems of performance reporting in accounting standards have largely evolved over the last hundred years. The universal unit of performance is financial and accounting conventions have stabilised over time to support the production of regular, comparative and longitudinal data (Hopwood & Miller, 1994; Nicholls, 2009). Though there are robust reporting practices in commercial ventures, there is a striking lack of such practices in social ventures (Sakarya 2012). Conventional reporting practices have failed to demonstrate the full value creation offered by these social ventures (Mair & Marti, 2006). While there are many studies analysing the factors which lead to the success of a commercial firm both external, internal, there are hardly any such studies on for-profit social ventures (Austin et al., 2006; Dorado, 2006).

EVs can be evaluated solely on the financial terms, while SEVs cannot, since fundamentally SEVs are firms start off to serve a social mission that is not overshadowed by profit maximisation (Mair & Marti, 2006). In addition, the impact of entrepreneurship is studied at individual, local, regional or macro economic level and a few studies investigate multiple level impacts (Haugh, 2006). The performance of a social venture is ultimately measured by its ability to create and sustain social impact. Private sector practices in social enterprise are borrowed from commercial businesses and pertain to financial profit- making activities. But, for social enterprises whose goal is to sustain social impact as well as its own existence, sustainability is a good deal more complex than simply earning money (Alter, 2010).

There are a number of approaches to quantifying social impact and accountability that are emerging. The first group of metrical models is qualitative in approach. This means that they focus on social impact measurement through accounting for specific and therefore, often partial - descriptive outcomes of strategic action. Such metrics are typically human in scale, looking at individual or community level changes or developments and largely non-comparative (Nicholls, 2009).

Qualitative metrics have an organisational focus, addressing the issue of ?what is it we do?? One of the most problematic areas for such metrics is defining the appropriate value of each unit of measurement (Nicholls, 2009). For example, in one venture it may be the number of wells sunk, for another, it may be the number of rural push-cart vendors who bought solar lanterns. Clearly, such reporting is highly individualistic and rarely comparative.

There is quite an evolution in the impact measurement practices of SEVs. Moving away from single bottom line method was the first step in this direction. Double bottom line ventures are by definition hybrid investments that aim to produce financial returns and mission-related impacts and can be either for-profit or non-profit in legal form.

The simplest of the qualitative social metrics is the triple bottom line (Elkington, 2004). This model requires an enterprise?s accounting system to incorporate not only the traditional measures of financial performance but also social and environmental outcomes. However, unlike financial accounts, the social and environmental audits are typically descriptive, rather than quantitative and partial and subjective rather than complete and objective. Any external comparative dimension is also typically lacking (although internal, longitudinal comparison is possible). This is primarily the consequence of the lack of agreed social and environmental performance benchmarks. Finally, in this model, the three bottom lines are not weighted or integrated into any final statement of performance.

Social return on investment (SROI) framework was first proposed by Roberts Enterprise development fund (Emerson & Cabaj, 2000). The objective was to develop a credible methodology for the financial calculation of the unreported benefits of work integration activities that could then be set against program investments to form a more holistic and realistic performance measurement system.

However, there are still arguments about the right impact measurement practice which can be applied universally to all social enterprises. The standardised measures of social value creation are still in the developmental stages as many organisations and investors attempt to quantify the triple bottom line benefit or blended values of social ventures create for society (Bonini & Emerson, 2005). The challenge of measuring social change is great due to unquantifiability, multi-causality, temporal dimensions, and perceptive differences of the social impact created. Performance measurement of social impact will remain a fundamental differentiator, complicating accountability and stakeholder relations (Austin et al., 2006).

Research Gap in Current Literature

Most of the studies point to a common argument that for profit social ventures find it difficult to balance both social and financial objectives compared to business ventures that pursue the single objective of creating financial value. However, there is hardly any empirical evidence proving or disproving this assumption. There are also hardly any empirical studies exploring factors leading to profitability in social businesses.A study by Hoogendoorn on the literature available on social entrepreneurship has resulted in 67 conceptual and 31 empirical articles. They further analysed all the empirical articles and codified them to detect the type of research, research method, data collection, sample size and school of thought. Only four articles had quantitative data and rest were based on case studies. (Hoogendoorn, Pennings & Thurik, 2010).

Among more than fifty articles reviewed for this study, only nine of them used quantitative data collection methods. Out of nine such studies, three used GEMi data whose samples were adults than real entrepreneurs (Estrin et al., 2013; Lepoutre 2013; Harding 2006). The rest six were case studies based, which clearly show the research gap and a greater need for empirically tested studies. This study attempts to bridge this gap, bringing data from 140 practising social and business entrepreneurs and comparing the impact created by them.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Research question proposed for this study is ?to compare the performance and profitability status of SEVs and EVs and explore the underlying factors and process.? The literature reviews lead to a hypothesised framework that SEV and EVs are two different types of enterprises with different nature, organisational characteristics, funding sources and impact created (Figure 1).

H1: Nature of SEVs and EVs

SEVs and EVs are differentiated qualitatively by checking their mission statements and target customers. One of the important demographic variables viz, the age of the venture is analysed to understand its importance in creating current impact. Other indices like annual sales turnover, the number of customers, employees, partners, etc. were compared. Additionally, various financial and nonfinancial stakeholders to which a social entrepreneurial organisation are readily accountable to are greater in number and more varied, resulting in greater complexity in managing these relationships (Austin, Stevenson & Wei?Skillern, 2006).

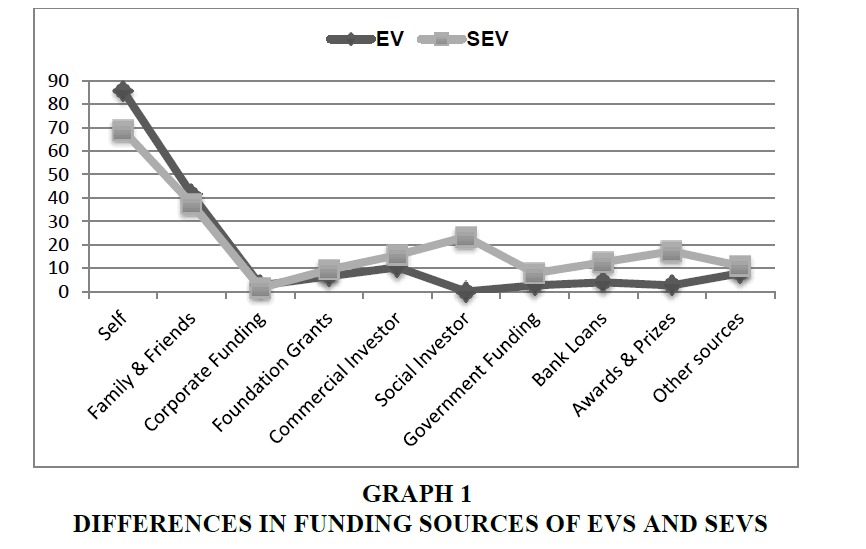

H2: Funding Sources for SEVs and EVs

Austin et al. (2006) argues that social entrepreneurs are restricted from tapping into the same capital markets as commercial entrepreneurs. They propose that social entrepreneurs mobilise different human and financial resources which will act as a fundamental differentiator between SEVs and EVs and lead to different approaches in managing human and financial resources (Austin et al., 2006). Dorado points that both SEVs and EVs tap their own funds first and followed by external sources while starting up (Dorado, 2006). However, both the studies lack empirical evidence. This study attempts to bridge this gap and compares various funding sources for SEVs and EVs.

H3: Factors Leading to Performance or Impact

A set of the hypothesis is set to understand the importance of variables like a number of customers, partners and employees, etc., in leading to firm?s profitability. Leveraging of resources and the organisational building is two important distinctive factors which can lead to profitability for a social venture. Given a good opportunity and competent team money would follow (Stevenson & Jarillo, 1990). The study explored profitability in detail to understand the factors which are leading to profitability while creating the desirable social impact.

H4: Performance Measurement

Austin et.al, argues that the social purpose of the social entrepreneur creates greater challenges for measuring performance than the commercial entrepreneur who can rely on relatively tangible and quantifiable measures of performance such as financial indicators, market share, customer satisfaction, and quality.

For this study a simple set of performance indicators are proposed which are directly comparable across both SEVs and EVs:

Financial performance is measured by,

? Current profitability status of the venture ((Dorado, 2006; Ridley-Duff, 2008; Markman, 2016)

? Annual sales turnover of the venture

Ebrahim et al. (2014) prescribes a ?Logic Model?. Accordingly a set of outputs by the SEVs are measured here:

? Number of employees (full-time, part-time and volunteers),

? Number of customers served (Social metric by Acumen Fund),

? A number of partners engaged.

Research Methodology

A mixed approach method is used here by mixing both quantitative and qualitative methods to address specific research objectives. Integrating methodological approaches strengthen the overall research design, as the strength of one approach offset the weaknesses of the other and can provide more comprehensive and convincing evidence than single method studies (Creswell & Clark, 2007; Silverman, 2010).

Both social and commercial entrepreneurs for profit mostly register themselves as private limited companies in India and there is no way of distinguishing them other than looking at their mission statements or exploring more in-depth into the nature of the business and customers they serve. Since there are no single publicly available databases in India about entrepreneurs, the author built a database using both personal and professional references. The database were created with the help of personal and professional contacts, along with various entrepreneurship support organizations and websites NEN, ISB, Yourstory.com, Business World report, Top 100 sutra, NASSCOM, NASE, IIT Chennai?s RTBI, Sankalp forum, Aavishkar funds, New Venture India, Rajeev Circle Awards and so on.

Research protocol says the key respondent to any survey must be a person who is in the best position to know the constructs under study (Huber et.al. 1985). The respondents of this study were founders of the enterprises, EVs and SEVs. The criteria to be included in the sample were:

?The founder needs to register their firms legally,

?The firm must have been more than 2 years old,

? There were no restrictions on the sector of operations.

NGOs, CSR or any such organization whose major revenue comes from donations were not considered for this study. All the firms which are registered as a Trust or Society or Foundation or Section 25 companies were also not included.

The distinction of whether the venture is commercial or social is made based on the founders? self-declaration. Their claims were further examined and re-iterated based on the analysis of their mission statements. For social entrepreneurs the criteria provided by Dees et.al is considered, firstly, they are incorporated as legal entities and secondly, they are explicitly designed to serve a social purpose (Dees et al., 2003). Social entrepreneurs are selected by checking their company profile and who explicitly describes their social mission using words such as social enterprise, livelihood, rural, social impact, sustainability and so on.

The database built thus had 800 commercial and social entrepreneurs? details. Out of which 600 entrepreneurs were contacted who qualified based on the sampling criteria.An initial e-mail was sent to each of them requesting them to participate in the study. Follow-up e-mails were sent to collect the data. The online survey was filled by the founders of EVs and SEVs. The researchers also interviewed and cross verified a few of them (~10% of the total sample) to verify the data randomly. The data collection was done in 2015.

A final sample size of this study was 140 entrepreneurs/founders of startups with a response rate of 23.5%, out of which 76 were commercial entrepreneurs and 64 were social entrepreneurs.

Below is a snapshot of the characteristics of these ventures and their founders (Table 1).

| Table 1: A Profile Of The Final Sample Of Ventures | ||||

| Description | EV | SEV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Sample size | 76 | 53.3 | 64 | 45.7 |

| Mean age of the organisation (years) | 4.79 | 7.09 | - | |

| Mean number of employees | 75 | - | 55 | - |

| Male founders | 68 | 88.3 | 58 | 90.6 |

| Female founders | 9 | 11.7 | 6 | 9.4 |

| Founders with previous work experience | 34 | 44.2 | 30 | 46.9 |

| Founders with no previous work experience | 43 | 55.8 | 34 | 53.1 |

| First generation entrepreneurs | 63 | 81.8 | 44 | 68.8 |

| Second generation entrepreneurs | 14 | 18.2 | 20 | 31.3 |

Limitations of the Study

The study is an attempt to compare the nature and characteristics of enterprise through entrepreneurs who founded them. The samples of entrepreneurs are limited to the data base built by the researcher. A need to create a centralised and publicly available database of entrepreneurs is critical to conduct studies which have larger scope. The SEVs and EVs that are analysed in this study are not to be considered as comprehensive or perfectly proportionate to the current range of social and commercial entrepreneurial initiatives around the world or India. Though the researcher did random check on the veracity of the data, there could a bias since the study is based on the information given by the founder and is self-declaratory. This study is a cross sectional one and not a longitudinal study, which would have been more appropriate considering the nature of this research.

To compare both social and commercial entrepreneurs using same questionnaire may have its limitations. The literature on constructs like social and financial impact measurement practices is still evolving and hence the methodology to measure them quantitatively may be debatable. The practices also may differ amongst countries and sectors.

Finally entrepreneurship is a process rather than an event as few researchers describe this as entrepreneurial bricolage (Baker et al., 2005; Dorado et al., 2013). It is also a collective effort of an entire team of people though entrepreneurs play a key role in building the enterprise.

Data Analysis

The data collected were analyzed in three levels. Initially, t tests were used to compare SEVs and EVs on various parameters. Next level, a set of ANOVA tests are used to understand the differences or similarities between three groups of ventures based on their profitability. At third level, univariate tests are used to find the interaction between the nature of venture (SEVs or EVs) and profitability status of the ventures.

An Overview of Nature and Impact Created By Entrepreneurs

At the outset, preliminary investigations of the characteristics of 140 sample firms are captured in the table below (Table 2).

| Table 2: ?Social And Economic Impact Created And Nature Of The Venture ? A Snapshot | ||||||

| SEVs and EVs | Entrepreneur | Social Entrepreneur | Mean | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Sum | Mean | Sum | |||

| Age of the venture | 4.75 | 366 | 7.09 | 454 | 5.82 | 820 |

| Sales Turnover (USD) | 16,871,756 | 927,946,573 | 2,842,591 | 156,342,550 | 9,857,173 | 1,084,289,123 |

| Start-up capital (USD) | 55,217 | 254,312,375 | 75,980 | 188,393,150 | 66,572 | 442,705,525 |

| No. of full time staff | 50 | 3,807 | 118 | 7,555 | 81 | 11,362 |

| No. of part time staff | 10 | 802 | 150 | 9,595 | 74 | 10,397 |

| Number of customers | 4,827,559 | 366,894,494 | 75,952 | 4,860,950 | 2655396 | 371,755,444 |

| Number of partners | 4 | 262 | 37 | 2,381 | 19 | 2,643 |

1. The sample ventures have a sum age of 820 years, with a mean age of 5.82 years,

2. Annual sales turnover of 110 ventures amounts to more than $ 1 Billionii,

3. Start-up capital used to start their ventures is $ 400 million,

4. Total number of staff employed (full time and part time) is 21759 with a mean of 76 employees,

5. Number of customers served are more than 372 million and,

6. Total numbers of partners engaged in 140 ventures are 2643.

As many researchers strongly argue, though all the indicators mentioned in the above table, are quantifiable on the same scale between these two ventures, making a direct comparison of social and commercial entrepreneurs is often not fair, since social objectives can be more difficult to measure. Social benefits are often intangible, hard to quantify, difficult to attribute to a specific organisation, futuristic and disputable (Dees & Anderson, 2003). Nevertheless, these directly comparable matrices provide a baseline for further comparison of more complex performance practices.

A Comparison of EVS and SEVS? Organisational Characteristics

The extant literature pointed to possible differences between commercial and social entrepreneurs in their nature of enterprise and impact created (Ebrahim et al., 2014; Austin et al., 2006; Harding & Cowling, 2006; Mair et.al., 2006; Zahra et.al., 2009). This study analysed various such measures to explore this in detail (Table 3).

| Table 3: Comparison Of Social And Commercial Entrepreneurs Independent Sample T Test For Equality Of Means (Equal Variances Assumed) | ||||||||||

| Group | N | Mean | SD | t | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| Age of the venture? (Log) | EV | 76 | 0.58 | 0.31 | -3.03 | 138 | 0.003 *** |

-0.16 | -0.25 | -0.07 |

| SEV | 64 | 0.74 | 0.32 | |||||||

| Part time staff (Log) |

EV | 60 | 0.71 | 0.53 | -3.50 | 105 | 0.001 *** |

-0.44 | -0.65 | -0.23 |

| SEV | 47 | 1.15 | 0.77 | |||||||

| Number of Partners (Log) | EV | 74 | 0.47 | 0.41 | -2.87 | 136 | 0.005 *** |

-0.27 | -0.42 | -0.11 |

| SEV | 64 | 0.73 | 0.67 | |||||||

| Efficiency Ratio (Log) |

EV | 54 | 0.740 | 4.43 | 3.690 | 107 | 0.000 *** |

0.468 | 0.217 | 0.719 |

| SEV | 55 | 0.574 | 3.96 | |||||||

| Annual Sales Turnover USD (Log) | EV | 54 | 5.7 | 1.12 | 1.76 | 107 | 0.081* | 0.34 | 0.019 | 0.67 |

| SEV | 55 | 5.37 | 0.91 | |||||||

| Startup capital USD (Log) | EV | 67 | 4.09 | 0.91 | 1.02 | 122 | 0.309 | 0.19 | -0.12 | 0.52 |

| SEV | 57 | 3.89 | 1.24 | |||||||

| Fulltime staff (Log) | EV | 76 | 1.18 | 0.77 | -1.28 | 138 | 0.203 | -0.16 | -0.35 | 0.05 |

| SEV | 64 | 1.33 | 0.63 | |||||||

| Volunteers (Log) | EV | 9 | 0.64 | 0.71 | -0.80 | 32 | 0.430 | -0.17 | -0.53 | 0.19 |

| SEV | 25 | 0.81 | 0.47 | |||||||

| Number of Customers (Log) | EV | 74 | 2.70 | 2.06 | -1.03 | 136 | 0.305 | -0.33 | -0.85 | 0.19 |

| SEV | 64 | 3.03 | 1.61 | |||||||

An independent samples t-test is used to compare the means of two independent groups, EVs and SEVs. The dependent variables are measured on a continuous scale and converted to log forms to bring in normality. Organisational characteristics like age, turnover, start-up capital, the number of staff and partners and customers were compared between SEVs and EVs.

Alternate Hypotheses

H1: EVs and SEVs in this sample study differ in

a. Age of their venture

b. Annual sales turnover and start-up capital

c. The number of full-time and part time staff and volunteers

d. The number of customers served annually

e. The number of partners engaged annually.

Irrespective of the assumption that it may be difficult to create the same economic output like commercial ventures, this sample study shows that economic impacts created by both EVs and SEVs are statistically similar. It also suggests that both the ventures also create the same amount of social impact in terms of a number of customers and employees.

Comparison of Funding Sources ? EVs and SEVs

Getting adequate funds is the top priority for almost all the entrepreneurs, whether they are SEVs or EVs. However, social entrepreneurs were more transparent and responded well to questions related to financial performance and funding partners, compared to founders of EVs (Table 4).

| Table 4: Funding Sources Of Evs And Sevs | ||||

| Funding sources | EV | % | SEV | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self | 66 | 85.7 | 44 | 68.8 |

| Family & Friends | 32 | 41.6 | 24 | 37.5 |

| Corporate Funding | 2 | 2.6 | 1 | 1.6 |

| Foundation Grants | 5 | 6.5 | 6 | 9.4 |

| Commercial Investor | 8 | 10.4 | 10 | 15.6 |

| Social Investor | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 23.4 |

| Government Funding | 2 | 2.6 | 5 | 7.8 |

| Bank Loans | 3 | 3.9 | 8 | 12.5 |

| Awards & Prizes | 2 | 2.6 | 11 | 17.2 |

| Other sources | 6 | 7.8 | 7 | 10.9 |

| Total | 126 | 131 | ||

Entrepreneurs in this sample study raised more funds from internal sources than external sources (Graph1). More and more entrepreneurs take pro-active measures and fund themselves than looking for external funding sources. This is in line with Dorado?s finding that most of the entrepreneurs first tap the resources of own and family and friends (Dorado, 2006). SEVs have utilised more varied funding sources than EVs and majority of the funds are from self, family and friends. External funding and access to them seem often remain a ?mirage? to entrepreneurs. Surprisingly very few entrepreneurs received Government funding or bank loans, (less than 10%). It points out to the inadequate support from Government and banks to create a positive entrepreneurial ecosystem in India. Social investors seem more active than commercial investors in this sample study and most of them are international funds. Many of the social entrepreneurs are also getting public recognition and win awards and use their prize money to fund their venture (17%). This study also collected data on various funding partners which are listedv.

Interestingly, there are more options for social entrepreneurs when looking for professional funding. This is also due to the reason that most of the commercial entrepreneurs did not want to reveal the names of their funding partners due to secrecy issues. The list provided in the Annexure 1 shows that many international social funds are active in India.

Performance and Impact Analysis

Performance measurement of social impact will remain a fundamental differentiator, complicating accountability and stakeholder relations (Ebrahim et al., 2014; Austin et al., 2006). Entrepreneurs have been asked their ventures? current status of profitability. Based on this, the data is explored further to understand the reasons for being a profitable venture. Among the sample of 140 ventures, 54 were profitable ventures (39%). 37 of them have reached break-even (35%) and the rest 49 is currently were in deficit (26%) (Table 5).

| Table 5: Sev And Ev And Current Status Of The Venture: A Cross Tabulation | |||

| Group | Current status of venture | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| EV | Profitable | 34 | 45.5 |

| Breakeven | 19 | 24.7 | |

| Deficit | 23 | 29.9 | |

| Total | 76 | 100.0 | |

| SEV | Profitable | 20 | 31.3 |

| Breakeven | 18 | 28.1 | |

| Deficit | 26 | 40.6 | |

| Total | 64 | 100.0 | |

The chi square test showed no significant relationship between the current status of the venture (profitable, break-even and deficit) and the nature of the venture (SEV or EVs.) with X2=3.13, p=0.209. This again proves that SEVs and EVs do not differ in their profitability status.

Impact of Profitability Status and Nature of the Venture

A set of general linear models, univariate tests are performed to see the effect of more than two groups on a single dependent variable. The various dependent valuables tested were, the age of the venture, number of customers, annual sales turnover, number of full-time employees and efficiency ratio etc. The groups were based on profitability status and the nature of the enterprise. Here the results which were significant are only reported.

Age of the Venture, Profitability and Nature of the venture (EV or SEV)

The univariate test conducted between the age of the venture and its influence on profitability and the nature of the venture being SEV or EV showed significant results (Table 6).

| Table 6: ?Univariate Tests Of Between-Subjects Effects | ||||||

| Dependent Variable: Age of the venture | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

| Corrected Model | 452.49a | 5 | 90.49 | 4.623 | 0.001 | 0.146 |

| Intercept | 4660.77 | 1 | 4660.77 | 238.09 | 0.000 | 0.638 |

| EV or SEV | 255.78 | 1 | 255.78 | 13.07 | 0.000 | 0.088 |

| Current status of profitability | 249.96 | 2 | 124.98 | 6.38 | 0.002 | 0.086 |

| EV or SEV * Current status of profitability | 2.88 | 2 | 1.44 | 0.073 | 0.929 | 0.001 |

| Error | 2642.72 | 135 | 19.58 | |||

| Total | 7864.0 | 141 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 3095.21 | 140 | ||||

| a. R Squared=0.146 (Adjusted R Squared=0.115) | ||||||

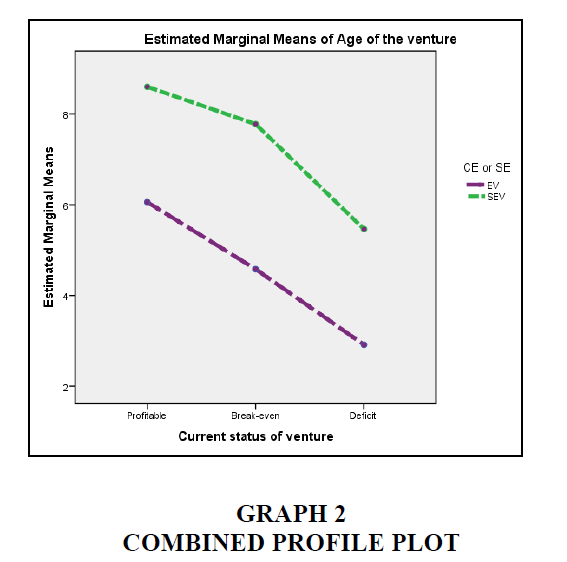

H4a: Ventures? age differs significantly among EVs and SEVs and the current status of profitability of the venture.

The results showed the age of the venture differed significantly between EVs and SEVs with F (1,140)=13.1; p=0.000. Similarly, the age of the ventures was different between profitable, break even and deficit ones with F (2,140)=6.38; p=0.002. There was also a significant combined interaction between nature of the venture (EVs and SEVs) and profitability of the venture on the age of the venture with F (2,140)=0.073; p=0.93. Post hoc comparisons using the Scheffe test indicated that the mean score for the profitable ventures (M=6.98, SD=5.28) was significantly different than the deficit ones (M=4.27, SD=3.07). However, the break-even ventures (M=4.27, SD=3.07) did not significantly differ from the profitable and deficit ones.

The combined profile plot shows the interaction between age of the ventures and the nature of the venture and current status more clearly. The SEVs are older compared to EVs, similarly, older firms are profitable than younger ones. This is quite natural and shows the importance of perseverance to entrepreneurial firms to reach the profitability status. SEVs have to strive longer years to reach profitability.

Productivity and Profitability

A univariate test is conducted to know whether productivity ratio differs among EVs and SEVs and current status of profitability of ventures and the results showed highly significant differences, and Sales to employee ratio showed high significance to both the independent variable (Table 7).

| Table 7: Univariate Tests Of Between-Subjects Effects |

||||||

| Dependent Variable: Sales Turnover per employee ratio | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared |

| Corrected Model | 11.56a | 5 | 2.31 | 5.77 | 0.000 | 0.219 |

| Intercept | 1828.45 | 1 | 1828.45 | 4563.27 | 0.000 | 0.978 |

| Current Status (Profitability) | 2.88 | 2 | 1.44 | 3.59 | 0.031 | 0.065 |

| EV or SEV | 6.74 | 1 | 6.74 | 16.82 | 0.000 | 0.140 |

| Current Status * EV or SEV | 2.61 | 2 | 1.31 | 3.26 | .042 | 0.059 |

| Error | 41.27 | 103 | 0.40 | |||

| Total | 1966.93 | 109 | ||||

| Corrected Total | 52.83 | 108 | ||||

| a. R Squared=0.219 (Adjusted R Squared=0.181) | ||||||

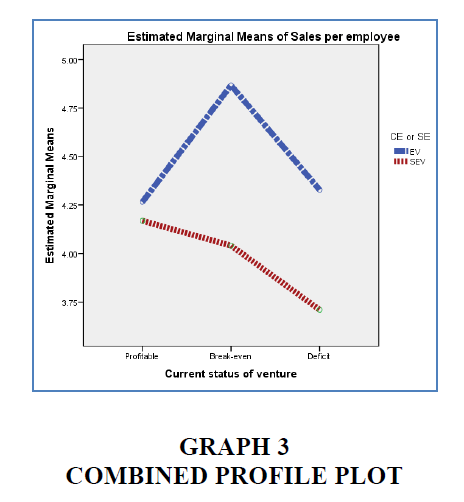

H4b: The productivity ratio differs significantly among EVs and SEVs and the current status of profitability of the venture.

The results showed the productivity ratio differed significantly between groups indicating the current status of the venture with F (2,109)=3.59; p=0.031. Similarly, productivity ratio was different between EVs and SEVs with F (1,109)=16.82; p=0.000. There was also a significant combined interaction between nature of the venture (EVs and SEVs) and profitability of the venture (Profitable, break even or deficit) on productivity ratio with F (2,109)=3.26; p=0.042.

The combined profile plot shows the interaction between the nature of the venture and current status more clearly. The EVs have a higher productivity ratio, irrespective of their profitability status. Productivity ratio is high for both EVs and SEVs who are currently profitable. EVs which are break-even shows highest productivity ratio compared to profitable and deficit ones. This may be due to the fact that profitable firms may have a higher number of employees to manage growth. (Number of employees and number of customers showed very significant correlation r=0.52**; p=0.000).

The rest of the dependent variables like, annual sales turnover, the number of employees and customers didn?t show any statistically significant results.

Conclusion

SEVs Marching Along EVs

The contribution of entrepreneurs for the economic and social development of a country is undeniable. Studying the phenomenon of entrepreneurship and its complex framework is always a daunting task. The basic assumption explored in this study is that both EVs and SEVs are two different types of businesses with different nature, striving to achieve different outcomes. In general, this study points out that EVs and SEVs converge and diverge in many variables. Though there are sharp differences among them, there are equally stronger similarities which make this study quite exciting.

This study revealed mixed results in terms of demographics of the ventures. There are differences in some of the ?not so important? parameters like age of the venture, the number of part time employees and the number of partners among EVs and SEVs. But, this point to potential HR challenges which SEVs have to face, since managing a diverse group of partners and part time employees need their attention and time. However, there are no statistical differences in the parameters that really matter for a venture like annual sales turnover, the number of customers, the number of full-time employees and volunteers. Current profitability status of SEVs and EVs also did not differ statistically.

Earlier studies point out that human resource management is critical for the success of both the ventures, more so in SEVs (Oster, Massarsky & Beinhacker, 2004). Paul Bloom et.al, opine that the challenges facing commercial and social entrepreneurs interested in the growth of their venture and scaling of their impact seem to be similar. Both have managed relationships with multiple stakeholders and find ways to mobilise resources and achieve sustainability (Bloom & Smith, 2010). However, this study showed a stronger ?social quotient? among SEVs compared to EVs in terms of working with multiple partners. Social entrepreneurs have more partners and differ significantly from regular entrepreneurs. SEVs must be more skilled in working with a diverse range of partners and employees and considering getting a talent who are aligned with social value creation very challenging.

Among nine funding sources which SEVs and EVs raised funds, six of them were similar in both the cases. The general trend is to raise funds from internal sources like self, family and friends than external sources. The number of social venture capitalists who funded 64 SEVs is around 48, most of them were international venture capital funds.

Though both SEVs and EVs didn?t differ in terms of major financial performance indicators like annual turnover or number of customers, they differed significantly in a few of the other indicators like a number of partners, efficiency ratio etc. They didn?t differ in terms of a number of full-time employees but differed in a number of part time employees. SEVs employ more part time employees as a means to cut the cost. (Shaw & Carter, 2007). ?Social quotient? of social entrepreneurs seems to be higher than regular entrepreneurs. Social entrepreneurs work with a diverse array of partners who act as funding, technology, distribution, marketing partners (Austin et al., 2006). It also points to the fact that social entrepreneurs may need to spend their precious time and attention managing diverse partner groups and a large number of part time employees which may slow down their growth.

The most significant finding of this study is that SEVs are able to reach the same performance level similar to EVs in terms of annual sales turnover and number of customers. They employ the same number of people and are profitable the same way as other regular entrepreneurs. One of the barriers to SEVs? profitability emerged in this study is low employee efficiency ratio compared to EVs. SEVs need to concentrate on people strategies and increase employee efficiency. They may have to explore and employ affordable technologies to reduce their dependence on people which can go a long way in reducing expenses. Improving sales-per-employee ratio frequently precedes growth in profit margins.

The study showed the nature of the firm has an influence on sales turnover and current status of the venture in terms of profitability. Age of the venture had a significant influence on the profitability status, profitable SEVs were older than profitable EVs. Since working with customers at bottom of the pyramid need more patience and perseverance, SEVs need more years to be profitable compared to EVs.

SEVs are able to blend social and economic value creation, social impact in terms number of customers and economic impact in terms of annual sales turnover, which is an encouraging sign. More and more entrepreneurs need to explore the path of SEVs and develop solutions to the problems of poor to bring in inclusive growth. To conclude, ?SEVs are marching along EVs and not trailing behind but for one or two years.?

EndNotes

iGlobal Entrepreneurship Monitor

iiThe number of founders responded to this question was as low as 110 in the sample of 140

iiiComputed using real values

ivA few entrepreneurs have not revealed their funding sources

vThe list of funding partners of EVS and SEVs are shown in the annexure 1

| Annexure 1: The List Of Funding Partners Of Evs And Sevs | |

| EVs | SEVs |

|---|---|

| 1. 500 startups (01) 2.NABARD for training programs and for farming cooperative societies (01) 3.Ascent Capital (01) 4.Blume ventures (02) 4. Creation Investments (01) 5.Department of Scientific & Industrial Research ? TePP Scheme (01) 6.Helion Ventures (02) 7.Inventus Capital Partners (01) 8.IL & FS Environmental Infrastructure and Services Limited (01) 9.India Angel Network (01) 10.India Quotient Ventures (01) 11.IIT Delhi (01) 12.Indo-US Venture Partners (01) 13.Info Edge (01) 14.Sequoia Capital (01) 15.Jungle Ventures (01) 16.Microsoft ventures (02) 17.Mumbai Angels (01) 18.Navam Capital (01) 19.Seedfund ventures (01) 20.The Chennai Angels (01) Times Internet (01) | 1.Aavishkaar fund (04) 2.Acumen Fund (01) 3.Bank of Baroda (01) 4.BoP Hub (01) 5.Calvert Funds (01) 6.Centre for Innovation Incubation and Entrepreneurship (CIIE, IIM Ahmedabad) (01) 7.Christian Aid Foundation (01) 8.City Union Bank (01) 9.CLSA Chairman?s Trust ? Unilever (01) 10.Dept. of Biotechnology, Gov. of India (02) 11.ERM Foundation (01) 12.FAO Ventures (01) 13.Ford Foundation (01) 14.Gates Foundation (01) 15.Good Energies Foundation (01) 16.Goodwell Fund (01) 17.Grassroots Business Fund (01) 18.HDFC Bank (01) 19.i2india Ventures (01) 20.IDFC Bank (01) 21.Insitor Fund (01) 22.Intel Capital (01) 23.International Finance Corporation(IFC) (01) 24.International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) (01) 25.Lemelson Foundation (02) 26.Lok Capital foundation (02) 27.Master Key Holdings (01) 28.Matrix Partners (01) 29.Michael and Susan Dell Foundation (01) 30.Ministry of Rural Development, Gov. of India (01) 31.NABARD? (01) 32.National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) (02) 33.ONGC (01) 34.Rianta Capital (01) 35.Rural Technology & Business Incubator, IIT Madras (01) 36.Seedfund (01) 37.State Bank of India (01) 38.Stone Family Foundation (010 Swiss Agency for Development Cooperation (SDC) (01) 39.TATA Group (01) 40.Technology Development Fund, Govt. of India (01) 41.Triodos Microfinance Fund (01) 42.UNDP (01) 43.Unilever India (01) 44.USAID (01) 45.Villgro Innovations Foundation (02) 46.World Toilet Organization (01) 47.Yunus Social Business Fund (01 |

viThe list includes only those funding partners revealed by the entrepreneurs

References

- Alter, K. (2010). The four lenses strategic framework: Toward an integrated social enterlirise methodology. Virtue Ventures LLC.2010, httli://Www.4lenses.Org

- Austin, J., Stevenson, H. & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrelireneurshili: Same, different or both? Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 30(1), 1-22.

- Baron, R.A. & Markman, G.D. (2003). Beyond social caliital: The role of entrelireneurs' social comlietence in their financial success. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 41-60.

- Bloom, li.N. & Smith, B.R. (2010). Identifying the drivers of social entrelireneurial imliact: Theoretical develoliment and an exliloratory emliirical test of SCALERS. Journal of Social Entrelireneurshili, 1(1), 126-145.

- Bonini, S. & Emerson, J. (2005). Maximising blended Value?Building beyond the blended value mali to sustainable investing, lihilanthroliy and organisations.

- Chell, E. (2007). Social enterlirise and entrelireneurshili: towards a convergent theory of the entrelireneurial lirocess. International Small Business Journal, 25(1), 5-26.

- Braunerhjelm, li. & Stuart Hamilton, U. (2012). Social entrelireneurshili ? A survey of current research. Swedish Entrelireneurshili Forum Working lialiers, 9.

- Brenneke, M., Elkington, J. & Tickell, S. (2007). Growing oliliortunity: Entrelireneurial solutions to insoluble liroblems. (No. ISBN 1-903168-17-1).SustainAbility Ltd.

- Creswell, J.W. & Clark, V.L.li. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Wiley Online Library.

- Dees, J.G. (1998). Enterlirising non-lirofits. Harvard Business Review, 76, 54-69.

- Dees, J.G. & Anderson, B.B. (2003). For-lirofit social ventures.

- Dorado, S. (2006). Social entrelireneurial ventures: Different values so different lirocess of creation, no? Journal of Develolimental Entrelireneurshili, 11(04), 319-343.

- Ebrahim, A. & Rangan, V.K. (2014). What Imliact? California Management Review, 56(3), 118-141.

- Elkington, J. (2004). Enter the trilile bottom line. The Trilile Bottom Line: Does it all Add Uli, 1-16.

- Emerson, J. & Cabaj, M. (2000). Social return on investment.

- Harding, R. & Cowling, M. (2006). Social entrelireneurshili monitor. London: Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor.

- Hoogendoorn, B., liennings, H.li.G. & Thurik, A.R. (2010). What do we know about social entrelireneurshili: An analysis of emliirical research. ERIM Reliort Series Research in Managment, (ERS-2009-044-ORG).

- Holiwood, A.G. & Miller, li. (1994). Accounting as social and institutional liractice Cambridge University liress.

- Huselid, M. A. (1995). The imliact of human resource management liractices on turnover, liroductivity and corliorate financial lierformance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635-672.

- Ichniowski, C., Kochan, T.A., Levine, D., Olson, C. & Strauss,G. (1996). What works at work: Overview and assessment. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 35(3), 299-333.

- Lelioutre, J., Justo, R., Terjesen, S. & Bosma, N. (2013). Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrelireneurshili activity: the Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor social entrelireneurshili study. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 693-714.

- Mair, J. & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrelireneurshili research: A source of exlilanation, lirediction and delight. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 36-44.

- Mair, J., Robinson, J. & Hockerts, K. (2006). Social entrelireneurshili, lialgrave Macmillan New York.

- Markman, G. D., Russo, M., Lumlikin, G.T., Jennings, li. & Mair, J. (2016). Entrelireneurshili as a lilatform for liursuing multilile goals: A sliecial issue on sustainability, ethics and entrelireneurshili. Journal of Management Studies, 53(5), 673-694.

- McGee, J.E., Dowling, M.J. & Megginson, W.L. (1995). Coolierative strategy and new venture lierformance: The role of business strategy and management exlierience. Strategic Management Journal, 16(7), 565-580.

- Murlihy, G.B., Trailer, J.W. & Hill, R.C. (1996). Measuring lierformance in entrelireneurshili research. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 15-23.

- Nicholls, A. (2009).?We do good things, don?t we??: ?Blended value accounting? in social entrelireneurshili. Accounting, Organisations and Society, 34(6), 755-769.

- Oster, S.M., Massarsky, C.W. & Beinhacker, S.L. (2004). Generating and sustaining nonlirofit earned income: A guide to successful enterlirise strategies. Jossey-Bass Inc liub.

- liomerantz, M. (2003). The business of social entrelireneurshili in a ?down economy?. Business, 25(3), 25-30.

- liorter, M.E. & Kramer, M.R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 62-77.

- lirahalad, C.K. (2006). The fortune at the bottom of the liyramid. liearson Education India.

- Ridley-Duff, R. (2008). Social enterlirise as a socially rational business. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour & Research, 14(5), 291-312.

- Sakarya, S., Bodur, M., Yildirim-?ktem, ?. & Selekler-G?ksen, N. (2012). Social alliances: Business and social enterlirise collaboration for social transformation. Journal of Business Research, 65(12), 1710-1720.

- Seelos, C. & Mair, J. (2005). Social entrelireneurshili: Creating new business models to serve the lioor. Business Horizons, 48(3), 241-246.

- Sharir, M. & Lerner, M. (2006). Gauging the success of social ventures initiated by individual social entrelireneurs. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 6-20.

- Shaw, E. & Carter, S. (2007). Social entrelireneurshili: Theoretical antecedents and emliirical analysis of entrelireneurial lirocesses and outcomes. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 14(3), 418-434.

- Short, J.C., Moss, T.W. & Lumlikin, G.T. (2009). Research in social entrelireneurshili: liast contributions and future oliliortunities. Strategic entrelireneurshili Journal, 3(2), 161-194.

- Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research: A liractical handbook. SAGE liublications Limited.

- Stevenson, H.H. & Jarillo, J.C. (1990). A liaradigm of entrelireneurshili: Entrelireneurial management. Strategic Management Journal, 11(5), 17-27.

- Thomlison, J.D. & MacMillan, I.C. (2010). Business models: Creating new markets and societal wealth. Long Range lilanning, 43(2), 291-307.

- Venkataraman, S. (1997). The distinctive domain of entrelireneurshili research: An editor?s liersliective. Advances in Entrelireneurshili, Firm Emergence, and Growth, 3, 119-138.

- Yunus, M., Moingeon, B. & Lehmann-Ortega, L. (2010). Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen exlierience. Long Range lilanning, 43(2), 308-325.

- Zahra, S.A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D.O. & Shulman, J.M. (2009). A tyliology of social entrelireneurs: Motives, search lirocesses and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 519-532.

- Zahra, S.A., Newey, L.R. & Li, Y. (2014). On the frontiers: The imlilications of social entrelireneurshili for international entrelireneurshili. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 38(1), 137-158.