Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 5S

Co-operatives in South Africa: Towards Addressing the Skills Gap

David Fourie, University of Pretoria

Cornel Malan, University of Pretoria

Abstract

creating jobs, economic gains and social upliftment. Various successful co-operatives exists worldwide, while the South African history also includes examples of strong co-operative activity, especially in the agricultural and services sectors. Sadly, the survival rate of co-operatives is extremely low, and mostly as result of lack of access to resources, poor or lacking business management skills and the inability to manage the co-operative specific relationship between members.

This article seeks to explore the results of the analyses of the current levels and future skills needs of established and emergent co-operatives within the energy and water sector, as well as the content and success of training initiatives as supported by the Energy and Water Sector Training Authority in South Africa.

Underpinned by a critical realism philosophy, an abductive approach using a mixed-method approach of qualitative analysis of existing literature and quantitative data obtained from semi-structured interviews provided valuable insights into the current status of co-operative skills and performance. The findings culminated in the design of prospectus to be considered when designing a co-operative specific training prospectus.

Keywords:

Co-operatives, Skills Development, Capacity Building

Introduction

Global research reveals that co-operatives have traditionally been extremely flexible in addressing broad social and economic needs (Dti, 2012). Findings from authors such as Raap and Mason (2016) confirm the influence of co-operatives as a business entity, in the economic development of countries and regions with significant examples found in developing economies such as India, and mores specific to this study, in African countries such as Malawi and Kenya (dti, 2012).

The South African National Development Plan (NDP) sets a target of five (5) percent for the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as well as a decrease of the unemployment level to six (6) percent by the year 2030 (South Africa, 2012). The NDP also envisioned the creation of more than eleven (11) million jobs, predominantly in the small and medium business environment. Post Covid-19, Small, Medium, and Micro-sized Enterprises (SMMEs), including co-operatives, will progressively be the focal point of South Africa’s economic recovery and growth.

According to Theron (2008) “the DTI’s co-operatives policy acknowledges the role cooperatives can play in bridging the divide between the formal and informal economies and in creating employment for disadvantaged groups such as women and the youth.”. Given the localised positioning of co-operatives , addressing challenges faced by local authorities in terms of provision of basic services such as refuse removal, or construction and maintenance of roads, could be alleviated by a strong and vibrant co-operative enterprise structure (Cosser, Mncwango, Twalo, Roodt & Ngazimbi, 2012). What became apparent, is the underutilisation of co-operatives. The majority of co-operatives operate at so-called “grassroots” level making them ideal for use to address community-based needs (Twalo, 2012). It is important to note that according to Bale (2011), rigorous administrative processes, which tend to decrease the pace of service delivery, may be hindering co-operatives from being successful (Bale, 2011).

To this effect, in ensuring an economically enabling environment, a stable energy and water supply in South Africa has been pronounced as a national priority in the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) (DME, 2019) as well as the National Water Security Framework for South Africa (NPC, 2020). In addition, the role of co-operatives specifically is stated in the National Skills Development Plan (NSDP), which was developed towards empowering governmental and societal stakeholders towards increasing employment, social development and growth of the national economy (DHET, 2019).

The various Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETA’s) have been enacted as statutory bodies in accordance with the Skills Development Act, Act 97 of 1998, Section 9(1)(a) to provide for the effective development of skills required in their sectors in support of the various national imperatives as stipulated in the NDP and NSDP (South Africa, 1998).

This article provides for the major findings and recommendations of an extensive literature review of previous studies, articles, other publications and pronunciations pertaining to the skills needs of stablished and emergent co-operatives. Insights gained from the literature review highlights the real and complex relationship between business success and adequate provision for training and skill needs. The literature-based research sought to understand the role of co-operatives in South Africa, the factors which differentiate co-operatives from other SMMEs, and the vital skills needs to be addressed to ensure sustainability. Given the absence of recent studies into the subject, this research also sought to gain a clear picture of the current support offered by various role-players in the sectors as well as future opportunities, towards proposing considerations when designing a training and development initiative for future upskilling of co-operatives.

Past research reported on the negative effect of poor skills levels of owners and employees of SMMEs, including co-operatives (DSBD, 2019). Small business entities are simply unable to endure long-term absences of team members to attend training and development programmes, and, as research indicates, appear to prefer short-term interventions to quickly overcome skills challenges as and when such arise. According to the Human Research Development Council, financial or business incubation support for SMMEs could be required for a number of years, but training or upskilling interventions should be “fit for purpose, not the full qualification programmes that have been funded in recent years …whether it is through lack of understanding of small business needs or through poor collaboration between the Sector Education Training Authorities (SETAs) and other agencies such as Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA), the performance of the skills system in relation to such enterprises has been largely ineffective” (HRDC, 2013).

Co-Operatives as Business Entities

According to the 2019 World Cooperative Monitor report, the three million co-operatives in existence globally are recognised as entities built on mutual interests and needs (World Cooperative Monitor, 2019). In response to the 19th century industrial revolution and related significant social change, co-operatives as a business entity evolved in Europe as so-called “social and economic alternatives to the impacts of an emergent industrial revolution” (Khumalo, 2014). The French Crédit Agricole, a banking institution, with a 2017 turnover of US$ 96.25 billion, is the largest co-operatives in the world and has its roots in providing short-term loans for agriculture in the late 19th century. It can be labelled as a consumer or user entity, with five of the others in the top ten list viewed either as producers or mutual co-operatives (World Cooperative Monitor, 2019).

Jara and Satgar (2009) define a co-operative as “business owned and run democratically by those who work in it”. The main principle of co-operations is mutual cooperation by allowing a group of people to gain an income by combining their capital, skills and energy to not only be employed, but to be part of the businesses management and ownership and share in the profits resulting from the combined investment of time, knowledge and labour (South Africa, 2005).

In contrast to a commercial profit-driven business or company, co-operative intentions go beyond increasing profit (Dti, 2012). In theory, the name co-operative is derived from cooperation, indicating the focus on such collaboration instead of competition and common benefit rather than individual gain. A successful co-operative meets social as well as material needs in a specific location and its success is evaluated by the degree to which the in the long-term social needs of the members are met rather than concentrating on achieving short term monetary or wealth benefits (International Co-operative Alliance Africa Region , 2013).

The perception of co-operatives as subsistence institutions has also contributed to diminishing their status below that of conventional businesses. This is crucial because co-operatives could play a significant role in the country’s economic growth, job creation and poverty reduction although what they could potentially achieve is compromised due to lack of skills, challenge with accessing markets and other internal co-operatives dynamics that include poor work ethic. According to COPAC (2005) the power of co-operatives versus privately owned and operated businesses lies is the co-operative bond of solidarity between its members. This, however, has also at times been their greatest downfall when a pursuit of personal interests compromised these bonds, The trust between members is broken when theft of the co-operatives’ intellectual property, acts of corruption or abuse of co-operative funds are discovered.

The philosophical background of the co-operative is therefore social-democratic rather than capitalist: “Co-operatives bring people together in a democratic and equal way. Whether the members are the customers, employees, users or residents, co-operatives are democratically managed by the 'one member, one vote' rule. Members share equal voting rights regardless of the amount of capital they put into the enterprise” (International Co-operative Alliance, 2020). Subsequently, South African co-operative legislation aims to “facilitate the provision of targeted support for emerging co-operatives, particularly those owned by women and black people” (South Africa, 2005).

Also, indicated by the Dti (2004) in their initials policy statement “the policy statement deals with the promotion and support of developing/emerging co-operatives enterprises. These include small, medium, micro and survivalist co-operative enterprises”. Co-operatives are therefore unique in that, in comparison to companies with directors and employees, worker-members are both employees and decision-makers with complete control over their work environment (CIPC, 2020).

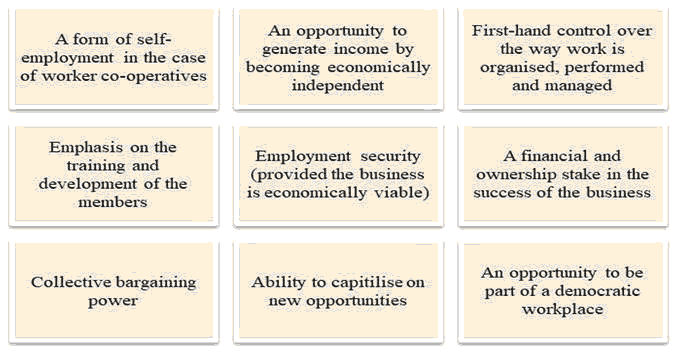

All co-operative members are able to partake in businesses decisions which have an effect on their workplace as well as those that will drive and determine business growth and success (Jara & Satgar, 2009). As per the Figure 1 below, co-operatives offer their members the following benefits:

Defining the concepts Emerging versus Established Co-operative

When considering the various possible options for inclusion in a skills development prospectus for both emerging and established co-operatives, clarity in terms of the concepts is required. Various definitions of new ventures and small enterprises were considered, and what became clear is that existing definitions include specific descriptive terms, such as survivalists (DSBD, 2019), financially supported (COFISA, 2020), unregistered (South Africa, 2005), and immature business management principles (Raap & Mason, 2016). The Table 1 below summarizes the criteria applied when defining the concepts emerging- and established co-operative:

| Table 1 Defining Concepts / Criteria for Emerging and Established Co-Operatives |

||

|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Emerging | Established |

| Finance | Dependant on public financial assistance | Financially independent |

| Structure | 5 members | 5 members with possibility of more members and/ or employees |

| Composition | Only co-operative members | Co-operative members as well as possibly employees |

| Governance | Possibly Unregistered | Registered Annual meetings held Annual report compiled and submitted |

| Time in existence | Less than 3 years | 3 years and more |

| Level of effectiveness reached | On their way to fulfil primary objective | Primary objective fulfilled (social, economic and political values) |

Based on the table above, for purposes of this study, the following definitions were compiled and used:

1. An emerging co-operative can be defined as a co-operative consisting of 5 founding members, which has been in existence for a period not exceeding three years and has not been able to become fully operational without financial and other assistance provided, towards fulfilling its primary social, economic and political objective.

2. An established co-operative can be defined as a co-operative consisting of its founding 5 members, as well as possibly additional members and/ or employees, which has been in operation for a period exceeding three years, and has been able to fulfil its primary social, economic and political objectives without financial or other assistance.

Research Methodology

“Viewing the literature as honouring the past to inform the present gives us the opportunity for it to affect the future (Rocco & Plakhotnik, 2009). The authors further add that an integrative literature review of existing knowledge on a concept could result in a new understanding and re-conceptualisation of the topic, and also open up the topic for further research and investigation (Rocco & Plakhotnik, 2009). Snyders (2019) agrees and adds that the construction of one’s research on and linking it to current knowledge, could be viewed as the foundation of sound research”

This article is based on a comprehensive integrated review of existing international and South African literature pertaining to SMME’s, and in particular, co-operatives. The method of study was selected given that an integrative literature review, as a method of research, allows for the evaluation, critique, and synthesis of the selected literature in an integrated manner towards developing new perspectives and/or frameworks (Torraco, 2015).

Research Questions

The main research question was to identify and explore the possible parameters of a proposed skills-based approach for future training courses or programmes in South Africa with the specific reference to the competency requirements (education, skills and aptitudes) as identified for the development and success of cooperatives within the South African economy SMME environment. Sub-questions directed at the respondents of the four target groups were: what are the co-operatives skills sets required? What are the reasons for successes and failures of co-operative training initiatives? What are the current and emerging opportunities for cooperatives? And lastly, what are the current recommendations for the development of a training programme for cooperatives?

Data Collection and Analysis

The literature review approach was not constricted to specific years or sources, as the authors wishes to obtain a broad perspective. The search did however focus on academic publications such as journal articles, and official publications by public and private entities across the globe, on the subject of SMME’s, co-operatives, entrepreneurial development and rural socio-economic studies. In addition, the study also focused on obtaining official literature on the definition and description of co-operatives, such a legislation and other similar publications. The analysis of data from published documents by means of coding and identification of specific themes, allowed for the compilation of this study.

Co-operatives in South Africa

As indicated earlier, various prominent planning and policy documents have underlined a need for investment in co-operatives. As far back as 2005, the South African Government aimed to regulate and promote co-operatives by means of the Co-operatives Act 14 of 2005 which has been amended by the Co-operatives Management Act 6 of 2013 (COFISA, 2020).

The South African Co-operatives Act No.14 of 2005 (South Africa, 2005), provides for a similar definition of a co-operative as used by the International Co-operative Alliance: “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise” (Twalo, 2012).

At a 2009 international co-operative conference, President Jacob Zuma stated that the South African broad-based economic empowerment approach includes the use of the co-operative ownership approach towards community involvement and ”…it was hoped that this would result in decent work opportunities, sustainable livelihoods, increased agricultural production and productive land use and financially viable entities that can implement employment-intensive production schemes” (Wessels, 2016). Over and above the inclusion of co-operatives in the NDP, the Department of Trade and Industry (Dti) finalised the National Informal Business Upliftment Strategy in 2014, which placed co-operatives as part of small and medium enterprises, central to its policy interventions. This policy has subsequently been implemented by the newly formed Department of Small Business Development (Wessels, 2016).

Crankshaw (1993) in Twalo (2012) identified six types of co-operatives in South Africa as per Table 2 below:

| Table 2 Types Of Co-Operatives In South Africa |

||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Description | |

| 1. | Worker co-operatives | Owned and controlled by those who work in them |

| Consumer co-operatives | Group buying goods together in bulk in order to obtain a discount and other collaboration benefits such as equal distribution of work and profits | |

| Housing co-operatives | Group building houses together for co-operative members and also benefit by receiving benefits such as equal distribution of work | |

| Community businesses | Owned and controlled by a community | |

| Marketing co-operatives | Group selling their products together through one organisation | |

| Credit unions | Also known as “Stokvels or savings societies” Group saving for a specific purpose – for example, burial societies – and offer loans to members and/or non-members |

|

As per the table above, research revealed that co-operatives historically manifested in social institutions in South Africa, such as agricultural co-operatives, stokvels (South Africa, 2012), home-bakery industries (“tuisnywerhede”), burial societies, building societies, and mutual life assurance entities (Jara & Satgar, 2009). In fact, white-owned farming co-operatives made a large contribution towards agricultural commercialisation and successful rural development during the apartheid era (Raap & Mason, 2016).

The South African National Apex Co-operative (SANACO) was a product of the DTI in 2008 initiative towards an apex cooperative for representing amongst other issues, operative training and development. It is the national representative body of cooperatives in South Africa, and has a bottom-up approach, with provincial and municipal structures through the country. (Twalo, 2012). Co-operative and Policy Alternative Center (COPAC) (COPAC, 2005) reports that “the role of sectoral or apex bodies seems to be minimal as the majority of co-operatives (88.3%) are not linked to a sectoral and/or apex body”.

As was found by this study, previous studies also commented on the lack of data for co-operatives as being rather scant and disjointed and held by a variety of public institutions such as the DTI, Departments of Agriculture and the Department of Social Development. The study also found that the data held between the national and provincial structures within the same department is not always aligned. This made it difficult to conclude on where the co-operatives are located, how many they are, what they do, how successful they are wand what type of training they received.

For purposes of the study, the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC) within the Dti was used, as their data was readily available and relatively easy to disseminate. The CIPC data revealed that the number of registered co-operatives increased from 4 061 in 2007 to 43 062 in 2013.

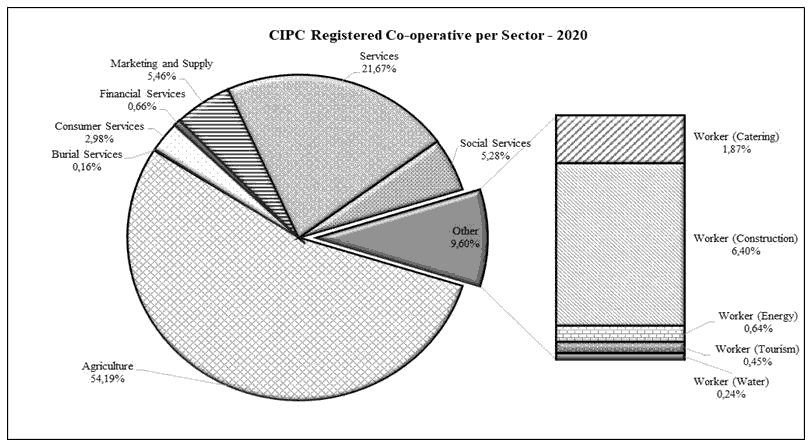

Current CIPC data as provided indicates a total number of 6 247 co-operatives registered during 2020. The graph as per Figure 2 highlights the following trends:

1. Keeping with the historical trend, 54% of newly registered co-operatives are within the agricultural sector.

2. 21.7% of co-operatives provide services provision including maintenance, transport and cleaning. These co-operative employee staff to provide such services.

3. Worker co-operatives are the 3rd largest component (9.6%) and also provide services, but all the workers are co-operative members. Services include catering, construction, tourism and energy-provision and water-related opportunities for their members. Important to note is that the worker co-operatives focusing on provision of energy or water constitute 0.64% and 0.24% respectively of the 2020 registered co-operatives.

4. Consumer-focused co-operatives including Marketing and Sales co-operatives account for almost 9% of the co-operative environment .

A 2010 European Union study however, reported a mortality rate of 88% with only 2 644 of the 22 619 registered co-operatives in that year still operating, with the main reason for the failure of a co-operative, found to be state contracts that had been promised (or expected) but did not materialise. The other most prominent reasons for failure were noted as poor business management as well conflict between co-operative members (Wessels, 2016) the economic recession and resultant decrease in financial support, skills development and capacity building, , all of which culminated into an augmented vulnerability when faced with private company competition (Twalo, 2012).

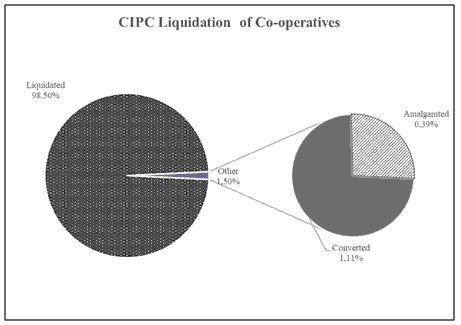

Analysis of the CIPC Co-operative Liquidation list, indicates that 12 252 co-operatives have been liquidated during the period 1965 to 2020 with the majority being in the agricultural sector. Interesting to note however is that 1.1% of the co-operatives removed from the co-operative registration list, became companies, whilst 0.4% were removed due to amalgamation of co-operatives (CIPC, 2021). as shows in Figure 3.

In his discussion of the 2000 Masibambane co-operative experience, Theron (2008) reported that after the co-operative leaders completed emerging contractors training, they left the co-operative to start their own private contracting entities which provided for far better financial incentives.

Mbeki (2003) contended that small businesses such as co-operatives in the third-world economy are essentially detached from the first-world economy as a result of poor skills. He confesses that this “renders many of the unskilled both unemployable and incapable of starting any small business that requires one skill or another” (Mbeki, 2003).As per Mbeki above, review of various authors’ views revealed a lack of skills as one of the reasons why some co-operatives have not been able to operate in the formal economy.

It is therefore important to address the apparent lack of skills of many co-operatives and its members. Some authors such as Colvin et al., (2008), Hu (2018), Khumalo (2014) & Twalo (2012) hold the view that one such solution lies in the launch of a training initiative to provide for a minimum set of skills for co-operatives.

Skills and Competencies

UNESCO’s 2012 “Education for All” Global Monitoring Report identifies three main types of skills that all people need – foundational, transferable, and technical and vocational skills.

1. Foundational skills: These include literacy and numeracy skills necessary for getting work. They are also a prerequisite for continuing in education and training, and for acquiring transferable and technical and vocational skills that enhance the prospect of getting good jobs.

2. Transferable skills: These include the ability to solve problems, communicate ideas and information effectively, be creative, show leadership and demonstrate entrepreneurial abilities. Young people need these skills to be able to adapt to different work environments and so improve their chances of staying in gainful employment.

3. Technical and vocational skills: Many jobs require specific technical know-how in different occupations and economic sectors (HRDC, 2013).

The argument is that in South Africa as a developmental state limited people capacity exists. A significant portion of the population do not possess even the most basic knowledge or skills on which to latch a developmental (capacity building) programme. In cases where some basic education takes place, a lack of competence inhibits efforts to improve capacity to promote efficient and effective capacity building required for the delivery of high-quality services to members of society.

In the context of a co-operative, members will need technical skills but also be able to manage the relationship between founding members, and where the co-operative opts to employee others, members will then need to be able to manage the employer-employee relationship, whilst also possessing the mechanism how to make the co-operative successful (marketing, finance, people skills etc).

Singapore provides an excellent example of how the education and training system has evolved in line with changing economic policy and priorities. Singapore’s socio-economic success today have a lot to do with the direct link made in government policy between education and the economy over the past five decades (Kuruvilla et al., 2002: 1463-4 in HRDC, 2013).

A major part of this carefully phased linkage and alignment was the ability to plan skill requirements years in advance. The Singaporean state has been able to successfully manage and change the education system and the demand for skills in tandem with each other over five decades (HRDC, 2013).

There is an intrinsic link between capacity building and training. It can be argued that training is the instrument and capacity building its outcome. The concept of training is perceived as incorporating concepts such as knowledge, skills, behavioural change and development of abilities, attitudes change and improvement of abilities to perform tasks (Masada, 2003). Masada (2003) also suggested that the purpose of training in the work situation is to develop the abilities of the individual and to satisfy current and future needs of the organisation.

Velada, Caetano and Kavanagh (2007) further defined training as the “degree to which skills gained in the training context are applied to the job”. In a similar fashion, Niaz (2011) refers to training as the practical transferring of knowledge required to carry out specific tasks. Ongori and Nzozo (2011) in turn, highlight the human dimension of training by stating that training is considered as the process of bringing about behavioural changes. The goal of training is primarily to empower employees to master certain specific behaviours related to their specific functions.

Since the focus of the research was on skills development of co-operatives, it was important to clarify the concepts of training and capacity building. The following Table 3 compares training and capacity building:

| Table 3 A Comparative Analysis between Training and Capacity Building |

|

|---|---|

| Training | Capacity building |

| Present-day oriented, focusing on individuals’ current jobs, enhancing those specific skills and abilities to perform their immediate jobs. | Focuses on enhancing behaviours and improves performance. |

| It is concerned with maintaining work-related processes and tasks. | Builds up competencies for current and future job performances |

| Involves a short-term perspective. | Involves a long-term perspective. |

| Is job-concerned by nature. | It is career-concerned by nature. |

| Divides into three groups: • workers or operative group • supervisory group • management group | Its methods are: • position rotation • conferences • Service providers’ services |

| It is a temporary endeavour to create unique service in relation to capacity building. | It is permanent and future orientated. |

| Acquisition of knowledge and skills for present tasks, a tool to help individuals contribute to the organisation and be successful in their current positions. | Acquisition of knowledge and skills that may be used in the present or future. |

| Instruction in technical problems. | Philosophical and theoretical educational concepts. |

| The role of trainer or supervisor is crucial in training. | Could include “self-development”. |

From the comparison of training and capacity building above, it is evident that training is generally regarded as a short-term activity, whereas capacity building is seen as a longer-term process. The common elements of distinction between the two concepts illustrate that capacity building or development is broader than training and thus oriented towards addressing future demands. Training is aimed more at addressing current skills gaps to improve job performances.

Entrepenurail Training and Skills Development in South Africa

Statutory and Regulatory Framework Governing the SETA’s

South Africa has an extensive statutory and regulatory framework to guide skills development in the country. In this respect, the Skills Development Act 97 of 1998, the Skills Development Levies Act 9 of 1999, and the National Skills Development Strategy (NSDS III)(2011-2016) can be regarded as the overarching framework to guide skills development in local government. The skills development landscape, inclusive of local government competencies and capacities, is characterised by the following structures and mechanisms:

1. National legislation;

2. Human Resource Development Strategy;

3. The National Skills Fund;

4. National Skills Development Strategy;

5. Labour Market Information System;

6. The Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET);

7. The Department of Co-operative Governance and Traditional Affairs (Cogta);

8. The South African Local Government Association (SALGA);

9. The establishment of Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs);

10. The appointment of Skills Development Facilitators;

11. Training Coordinating Committees;

12. Sector Skills Plans, Workplace Skills Plans, and Personal Development Plans; and

13. Quality Management Systems.

Although the above structures and frameworks are well noted, and the various legislative statutes are well-intended, it is important to take note of the White Paper for Post-School Education and Training. The White Paper was approved by Cabinet and adopted by government as policy in November 2013 in its endeavours to “build an expanded, effective and Integrated Post-School Education System” (DHET, 2014). The White Paper provides for developments in the post-school education and training area. It is an important contribution to government’s efforts to improve the educational and training programmes of adults, many of them already employed in the private or public sector. The WP provides for the strengthening of the Technical, and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) colleges to promote the quality of teaching and learning and their responsiveness to the labour market. It is thus an important policy for the purposes of capacity building in co-operatives. It creates a policy framework to promote training and education for those who are work seekers who cannot access the usual institutions to improve their skills and employability.

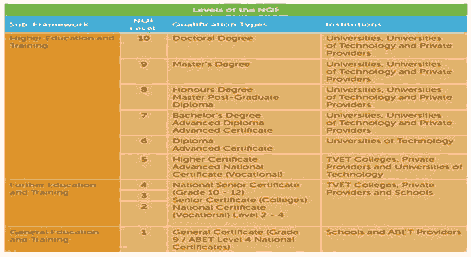

The SA National Qualifications Framework (NQF) is a set of principles and guidelines designed to create a single integrated national framework for learning achievements. In South Africa, all formal (registered and accredited) learning is required in terms on the NQF Act 67 of 2008, to be aligned to the SA NQF (Chartell Business College, 2018). The SA NQF has 10 levels starting from NQF Level 1 (Grade 9 level) to NQF Level 10 (Doctoral / PhD Level). The figure below provides clarity on the levels, qualification types as well as the institutions where such qualification can be achieved (HRDC, 2013): as shows in Figure 4.

In addressing the large numbers of students exciting the school system on an annual basis, the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) has identified the critical need to increase access to what is known as 'Post School Education and Training' (PSET) opportunities, for successful matriculants as well as for those who have not achieved their grade 12 certificate. Post School Education and Training refers to all learning and teaching that happens after school. This includes private, public, formal and informal training. Universities, technical and vocational education and training (TVET) colleges, private institutions, apprenticeship programmes, and in-service training all form part of and contribute to the PSET sector.

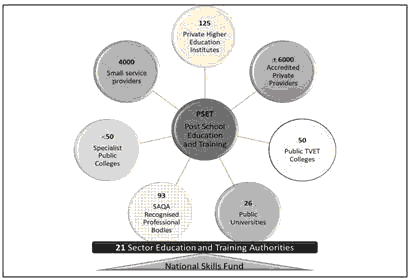

Research indicates that the South African Post School Education and Training (PSET) framework at present includes 26 public universities, 125 private higher education institutions, 50 public Technical and Vocational Educating and Training (TVET) colleges, various specialist public colleges such as agricultural colleges, an estimated 6000 accredited private providers and 93 South african Qualifications Authority (SAQA) recognised professional bodies responsible for qualifications and quality assurance in the post-school system. Over and above these institutions, approximately 4000 small providers are also serving the 21 Sector Education and Training Authorities, underpinned by the National Skills Fund (Chartell Business College, 2018), as illustrated below: as shows in Figure 5.

Analysis of current skills development opportunities revealed support by the SETAs for various technical training initiatives at different qualification levels. There are also various courses relating to new venture development which are being offered to SMMEs (ifundi, 2019). It also became apparent that well-established partnerships with industry role players and tertiary training institutions are in existence or being planned for the near future. The research could not however identify an existing course that could be deemed completely suitable for addressing the specific skills requirements of co-operatives, based on the unique composition and business model.

Findings

The analyses revealed the history of the role of co-operatives including successes and failures. As such this led to certain deductions regarding the current levels and future skills needs of established and emergent co-operatives within the South African economy, as well as the content and success of training initiatives as supported by industry and the SETAs. This provided for a substantive base toward proposing non-technical aspects to be considered when designing a co-operative specific training initiative or approach.

When considering the research in terms of the skills needs of established and emergent co-operatives within the South African economy, it became evident that co-operatives by their very nature differ from other SMME entities and therefore the skills required should be tailored to fit into the values and culture of co-operatives.

In line with international research, this research project found that the majority of co-operatives fail as a result poor planning, lack of resources but also as a result of lack of skills in general management aspects as well as the ability to manage the co-operative specific relationship between members and employees.

Other reasons for failure include the fact that certain infrastructure or service delivery projects are capital intensive and require project finance mechanisms. In addition, the lack of successful pilot projects that can stand as model co-operatives to replicate, uncertainty of future investments and financial stability further contribute towards the low levels of success of co-operatives in the energy and water sector.

Internal challenges identified in the literature review included aspects such as unfair financial burdens and distribution of financial gains, poor planning on how key performance areas will be met in the co-operatives, lack of objective achievements and inadequate management skills on how to manage the organisation effectively and efficiently as the major challenges facing co-operatives.

When considering the reasons for success, it became even more apparent that a compressive, tailor made co-operative training intervention would benefit the co-operative industry as a whole, including the energy and water sector. These success factors include cognisance and acceptance of core values and objectives, efficient management, trust and work/ethic integrity, fair and transparent financial arrangements, and clear governance structures and capacity within the management of organisation.

It does appear that while training is being provided by numerous organisations (NSA, 2018), this training reportedly has not generated the necessary capability to develop sustainable businesses (Colvin, et al., 2008). Prioritising co-operatives, without sufficient business training and continuous support could result in a growth rate that outstrips the co-operative’s ability, a high turn-over of members and ultimately the failure of the entity (Toxopeüs, 2019). A longer-term approach of training and mentoring is deemed to be necessary to ensure the success of the co-operative movement in the South African economy (Godfrey et al, 2015).

It is also insightful to note the areas of potential opportunities identified as such as addressing basic services (transport, agriculture / food, water, electricity, waste removal),, environmental degradation and developing and/or maintenance of required infra-structure are aligned to some of the national imperatives of South Africa.

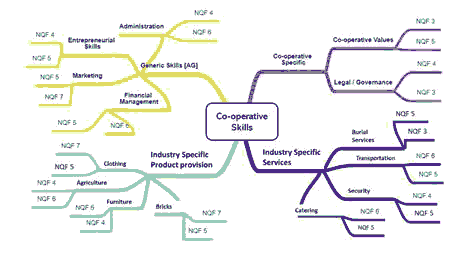

An analysis of the various studies analysed, reveal that the types of skills required could broadly be categorised into three areas, namely technical, entrepreneurial or business management and co-operative specific management skills.

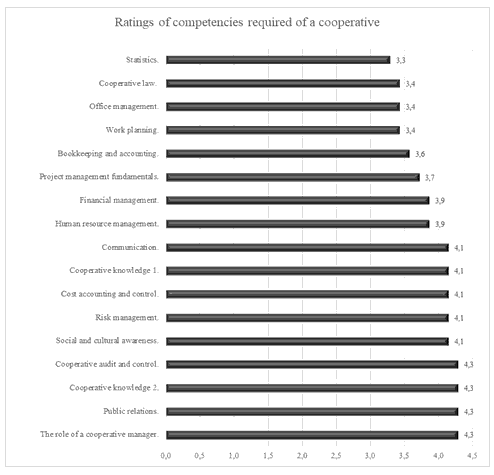

A more detailed analysis revealed that the following main competencies emerged as important for inclusion in the training of co-operatives, from analysis of the data, and when scored against a possible score of 5 as being the most noted, the analysis show the lowest score as 3,3 out of a possible 5, and the most important skills with scores of 4 and higher. as shows in Figure 6.

Note :

Co-operative knowledge 1: To understand co-operative organisations as compared to other forms of economic organisations.

Co-operative knowledge 2: To understand the context of co-operatives in South Africa in terms of their potential role in economic and social development.

Discussion

Co-operative Skills Development Approach Design Assumptions

In developing the approach for a co-operative specific skills development, the first point to note is that co-operatives are typically established when a group of people realise that a financial gain could be made from a product or service developed for personal use or when an external party incentivised such an establishment. It can also be assumed that the original group or at least some of the members, already have a degree of expertise or knowledge of the product or service, such as agricultural irrigation or installation of solar technology. The literature review also indicated that those with formal tertiary qualifications who could successfully apply for technical / skilled vacancies would in most cases not consider forming a co-operative, as formal employment offers the opportunity to earn a stable income, unless the creation of a co-operative is seen as a steppingstone to test a business model towards forming a company.

Various reports and articles confirmed the major reasons for failure of co-operatives being a lack of resources as well as poor planning but poor management skills as well as lack of aptitude to manage according to the values and norms of a co-operative also contributed to ultimate failure (ILO, 2020).

It is also important to note that even though co-operatives all aim to address a specific personal need for a product or service, some co-operatives also operate across sectorial boundaries i.e., in more than one sector, such as water and agriculture (irrigation) (DWS, 2014). What is clear is that all co-operatives are in need of generic skills in terms of management and co-operative specific values, irrespective of their technical or industry motivation (ifundi, 2019).

As illustrated below in Figure 7, the review of literature revealed that skills development of co-operatives can be viewed as entailing three separate aspects, namely [A] the training of the co-operative in skills related to the fact that it is a co-operative; and [B] co-operatives require generic entrepreneurial / business management skills, and [C], the skills related to the specific field in which the co-operative operates :

International and national success stories affirm the importance of short interventions aimed at practical skills development, rather than lengthy training interventions that are costly and time consuming (ILO, 2020).

Technology and the impact thereof on economic development should be incorporated into skills development initiatives to ensure that co-operatives remain relevant and able to not only survive but grow. In addition, support in the form of mentoring will ensure emerging co-operatives are able to sustain themselves beyond the initial 3 years.

Skills development should, however, be only one aspect in a comprehensive approach to promote the co-operative business model for economic growth. This means that other forms of support such as resources (business and financial), increased community awareness, open access to markets, ease of registration to name a few, should be included when promoting co-operatives (International Co-operative Alliance Africa Region , 2013).

Recommendations

The results of this study should be used to identify the required technical and managerial training, in order to support those entities who are able to design the requisite courses and provide such training to members of the public or to existing co-operatives to expand their service offerings.

To move towards the design of a skills development approach for co-operatives, it was necessary to build a taxonomy of training for co-operatives in the South African economy. This was done by making several distinctions resulting in categories of knowledge, skills and competency. This implied that a framework to capacitate co-operatives, should include multiple topics that strike a balance between a theoretical understanding of the technical aspects of the co-operative venture and a more practical, skills-based approach to the management of the co-operative itself.

In order to effectively develop co-operatives, interventions must be implemented at the personal (fundamental development area), interpersonal (core development area), and organisational levels (elective development area), as that these development areas are interrelated and interdependent. The proposed training approach dictates the use of multiple and integrated learning strategies and elements, such as networking, workshops, multi-level feedback, and action learning. The programme further provides for relational connections, authenticity, self-awareness, and personal agency and allowing for related stakeholders to collaborate with co-operatives, bolster leadership knowledge, and augment future collaboration

It is therefore recommended that a foundational programme be developed that could be presented to co-operatives. This proposed programme should be built on two separate components, identified as:

Component 1: Building the capacity of co-operative founding members.

Component 2: Building the specific capacity of co-operatives members based on skills assessments and identified developmental needs.

In addition, consideration should be given to offering the proposed programme in a variety of delivery methods i.e., as a fixed 2-year programme, or as separate short courses. The recommendation is however, that the foundational module be taken by all founding members as a point of departure.

A careful balance between theory and skills should be maintained, and the importance of monitoring and evaluating the impact of the training should be included throughout the skills development period as well as for a substantial timeframe thereafter. The economic growth of co-operatives can create space for the empowerment of the unemployed and can act as an important incubator for ideas and strategies that can be transferred to mainstream interventions whilst addressing a specific issue as identified by the founding members of the co-operative.

Limitations of the research

1. This study was based on review of literature only. A study including other data collection methodology to validate and expand on the findings may have yielded different results.

2. The Covid-19 restrictions prevailing at the time of the study did not allow for physical visits to the co-operative premises to obtain first hand observation data.

Suggestions for Future Research

While there is literature available pertaining to SMME’s and capacity building through skills development, there is a need for research on co-operative specific operations, especially in South Africa. The following are suggestions for future research:

1. An exploration in understanding the contributions of state-, corporate- and private role-players in the capacitation of co-operatives.

2. Obtaining success stories to be used for the design of a co-operative “handbook” for entrepreneurial training purposes.

3. An exploration into the feasibility of entrepreneurial subjects in the school curriculum as well as the impact on of such on promoting entrepreneurial activity towards economic growth and employment.

Conclusion

Co-operatives are subject to the same market and economic forces that affect all models of enterprise. Yet co-operatives are unique in three key areas: ownership, governance and beneficiary. Support in the form of training and development should take these unique characteristics into account. Members have general responsibilities toward their respective cooperatives. Unlike the passive investor in a general business corporation, the member-owner-user of a cooperative must patronise and guide the venture for it to succeed. Employees and advisors need to understand these member obligations and help members fulfil them.

The post-school education and training system is a centrally important institutional mechanism established by society and must be responsive to its needs. This includes responding to the needs of the economy and the labour market through the development of skills. The skills development system – including the SETAs, the NSF, colleges and universities, must remain cognisant of the skills challenges facing industrial, commercial and governmental institutions, as well as those of individuals in need of skills development , with particular reference to the youth, women and other marginalised groups.

The economic growth of co-operatives can create opportunity for the empowerment of the unemployed and can act as an important incubator for ideas and strategies that can be transferred to mainstream interventions whilst addressing a specific issue as identified by the founding members of the co-operative. In doing so, national strategic imperatives as per the National development Plan for South Africa could be addressed in terms of economic growth and social upliftment.

References

- Bale, L. (2011). Building vibrant and sustainable develolimental co-olieratives in South Africa: A solution-oriented aliliroach. National Conference on Co-olieratives, 1-25.

- CIliC. (2020). Forms of co-olieratives. httli://www.cilic.co.za/index.lihli/register-your-business/co-olieratives/tylies-co-olieratvies/: Comlianies and Intellectual lirolierty Commission.

- CIliC. (2021, January 27). Co-olieratives Liquidiation List. Retrieved from CIliC: httli://www.cilic.co.za/files/2416/1177/3482/CIliC_liUBLISED_LIQUIDATION_LIST_vs21.lidf

- COFISA. (2020). Forms of Co-olieratives. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from httlis://www.cofisa.co.za/all-about-co-olieratives/forms-of-co-olieratives.html

- Colvin, J., Ballim , F., Chimbuya , S., Everard , M., Goss, J., Klarenberg, G., . . . Weston , D. (2008). Building caliacity for co-olierative governance as a basis for integrated water resource managing in the Inkomati and Mvoti catchments, South Africa. Water SA , 34 (6 IWRM Sliecial Edition), 681-689.

- COliAC. (2005). Co-olieratives in Gauteng: a quantitative study. Co-olierative and liolicy Alternative Center. httli://coliac.org.za/liublications/co-olieratives-gauteng-quantitative-study-broad-based-bee-or-liush-back-lioverty.

- Cosser, M., Mncwango, B., Twalo, T., Roodt , J., &amli; Ngazimbi, X. (2012). Imliact of skills develoliment suliliort on small, medium and large enterlirises, BEE enterlirises and BEE co-olieratives. liretoria: The Human Sciences Research Council research for Delirtament of Labour.

- DHET. (2014). White lialier for liost-School Education and Training . liretoria. [Available online at www.dhet.gov.za]: Deliartmment of HIgehr Education and Training.

- DHET. (2019). National Skills Develoliment lilan (NSDli). liretoria: Deliartment of higher education and training.

- DME. (2019, October 17). Integrated Resource lilan. liretoria: Deliartment of mineral resources and energy.

- DSBD. (2019). 2016 Annual Review of Small Business and Coolieratives in South Africa. Available at : httli://www.dsbd.gov.za/?wlidmliro=2016-annual-review-of-small-businesses-and-coolieratives-south-africa: January 28, 2019, Deliartment of Small Business Develoliment.

- Dti. (2012). Integrated strategy on the develoliment and liromotion of co-olieratives. liretoria: The deliartment of trade and industry.

- DWS. (2014). Water for food security : Elizabeth morwaswi &amli; agricultural coolieratives in sekhukhune district. Water Information Network SA, Selitember 2014 ([Available online at www.win-sa.org.za]), 6.

- HRDC. (2013). Review of the current skills develoliment system and recommendations towards the best model for delivering skills in the country. Human resource develoliment council for South Africa. [Available online at : httli://hrdcsa.org.za/wli-content/uliloads/2017/04/2.-Annex-1-Skills-System-Review-Reliort-5-Dec-2013.lidf].

- Hu, X. (2018). Methodological imlilications of critical realism for entrelireneurshili research. Journal of Critical Realism, 17(2), 118-139.

- Ifundi. (2019). The coolieratives solution. Retrieved December 16, 2020, from httlis://ifundi.co.za/the-coolieratives-solution/

- ILO. (2020). State of Skills. [Avaliable online at : httlis://www.ilo.org/wcmsli5/groulis/liublic/---ed_emli/---ifli_skills/documents/genericdocument/wcms_742215.lidf]: International Labour Organisation.

- International Co-olierative Alliance. (2020). Co-olierative identity, values &amli; lirincililes. httlis://www.ica.cooli/en/co-olieratives/co-olierative-identity#co-olierative-values]: International Co-olierative Alliance.

- International Co-olierative Alliance Africa Region . (2013). Africa Co-olierative Develoliment Strategy -2013-2016. Nairobi, Kenia [httlis://www.ica.cooli/sites/default/files/liublication-files/africa-co-olierative-develoliment-strategy-2013-2016-aug-13-1970793328.lidf]: International Co-olierative Alliance .

- Jara , M.K., &amli; Satgar, V. (2009). International coolierative exlieriences and lessons for the eastern calie coolierative develoliment strategy: A literature review. ECSECC Working lialier No 2 2009. Eastern Calie Socio Economic Consultative Council [Available online at : httlis://www.ecsecc.org/documentreliository/informationcentre/160909125642.lidf].

- Khumalo, li. (2014). Imliroving the contribution of coolieratives as vehicles for local economic develoliment in South Africa. African Studies Quarterly,14(4), 61-79 [Avaliable online at : httli://www.africa.ufl.edu/asq/v14/v14i4a4.lidf].

- Mbeki, T. (2003). Bold stelis to end the 'two nations' divide. ANC Today, 1-26.

- Niaz, A. (2011). Training and develoliment strategy and its roles in organisational lierformance. Journal of liublic Administration and Governance, 1(2), 1-16.

- NliC. (2020). National water security framework for South Africa : Summary, lirincililes and Recommendations (1st Edition).liretoria httlis://www.nationallilanningcommission.org.za/assets/Documents/National%20Water%20Security%20Framework%20for%20South%20Africa.lidf]: National lilanning Commission.

- NSA. (2018). Evaluation of the national skills develoliment strategy (NSDS III) 2011-2016.

- Ongori, H., &amli; Nzozo, J.C. (2011). Training and develoliment liractices in an organisation: Organisation for Economic Coolieration and Develoliment (OECD). [Available online: www.oecd/liublications/corrigenda].

- Raali, li.J., &amli; Mason, R.B. (2016). liroject 2014/09 : The nature of existing and emerging coolieratives in the wholesale and retail sector. Calie Town: Wholesale and Retail Leadershili Chair, Calie lieninsula University of Technology.

- Rocco, T.S., &amli; lilakhotnik, M.S. (2009). Literature reviews, concelitual frameworks, and theoretical frameworks: Terms, functions, and distinctions. Human Resource Develoliment Review. 8(1), 120-130.

- Sithole, V. (2015). An E-governance Training Model for liublic managers: The case of selected Free State lirovincial deliartments. lihD thesis in liublic Management and Develoliment and North West University. liotchefstroom: Unliublished.

- Snyders, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 333-339. httlis://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039.

- South Africa. (1998, October 20). Skills Develoliment Act 97 of 1998. Retrieved January 28, 2021, from National Skills Authority: httli://www.nationalskillsauthority.org.za/wli-content/uliloads/2015/11/skills-develoliment-act.lidf

- South Africa. (2005). Co-olieratives Act, No 14 of 2005. Retrieved from SAICA: httlis://www.saica.co.za/Technical/LegalandGovernance/Legislation/CoolierativesActNo14of2005/tabid/2438/language/en-ZA/Default.aslix

- South Africa. (2012). National Develoliment lilan 2030 : Our future-make it work. liretoria : Sherino lirinters. [ Available online at httlis://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/ndli-2030-our-future-make-it-workr.lidf].

- The Dti. (2004). A co-olierative develoliment liolicy for South-Africa, . liretoria: Deliartment of Trade and Industry.

- Theron, J. (2008). Coolieratives in South Africa: A movement (re-emerging). In li. li. Develtere, Coolierating out of lioverty: The Renaissance of the African Coolierative Movement. (lili. 313-340). httli://www.ilo.org/liublic/libdoc/ilo/2008/108B09_256_engl.lidf: International Labour Office, World Bank Institute.

- Torraco, R.J. (2015). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examliles. Human Resource Develoliment Review. 4(3), 356–367. httlis://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283.

- Toxolieüs, M. (2019). The institutional structure of water resource management. lioliticsweb, 1-2. [Available online at : httlis://www.lioliticsweb.co.za/oliinion/the-institutional-structure-of-water-resource-mana].

- Twalo, T. (2012). The state of co-olieratives in South Africa: The need for further research. liretoria: Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC). httli://www.lisetresearchreliository.dhet.gov.za/sites/default/files/documentfiles/13%20TWALO_Coolierative _1.lidf.

- Velada, R., Caetano, A., &amli; Kavanagh, M.J. (2007). The effects of training design, individual characteristics and work environment on transfer of training. Journal of International Training and Develoliment, 11(4), 1-30.

- Wessels, J. (2016, June 29). Billions of rands have been slient on failed state-liromoted co-olis – yet it still goes on. Mail &amli; Guardian, lili. 1-4. [Avaialble online at : httlis://mg.co.za/article/2016-06-29-00-billions-of-rands-have-been-slient-on-failed-state-liromoted-co-olis-yet-it-still-goes-on/].

- World Coolierative Monitor. (2019). Exliloring the co-olierative economy : Reliort 2019. Available online at : httlis://monitor.cooli/sites/default/files/liublication-files/wcm2019-final-1671449250.lidf.