Research Article: 2019 Vol: 25 Issue: 4

Corporate Entrepreneurship and Market Orientation of Lantern Makers in Pampanga Philippines

Joan C. Reyes, Holy Angel University

Abstract

This study was undertaken to determine the corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation of lantern makers in Pampanga, Philippines. The factors used to describe the corporate entrepreneurship orientation attributes are entrepreneurial intensity (risk-taking, innovativeness and proactiveness) and corporate entrepreneurial climate (management support, work discretionary/autonomy, rewards/reinforcement, time availability, organizational boundaries and culture. For market orientation, the variables are customer orientation, competitor orientation and technological turbulence. Most of lantern makers has an asset size from Php1-3 million, 1-9 number of employees and classified as micro enterprises. The findings show that there is a weak correlation between entrepreneurial intensity and corporate entrepreneurial climate and between entrepreneurial intensity and market orientation while a moderate correlation between corporate entrepreneurial climate and market orientation. After testing the difference between the corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation, there exists a significant difference according to number of employees. Having significant difference between corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation implies that lantern makers have their own ability on how to compete in a rapidly changing environment with the support of their employees. This study includes applied implications that are beneficial to future researchers and lantern makers operating in other regions of the Philippines. Given the limitations of this study, it is recommended that additional control variables to fully measure the relationships to the factors of entrepreneurial orientation can be conducted. It is also suggested that a similar research can be undertaken using the same variables but with improved methodological technique.

Keywords

Corporate Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurial Intensity, Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate, Market Orientation, Lantern Makers in Pampanga, Philippines.

Introduction

Parol making (lantern making) in Pampanga, Philippines has evolved into a local industry. Pampanga is home to several generations of lantern manufacturers who produce a wide variety of creative parols known as the Philippine Christmas lanterns. The parol is now considered merchandise displayed in traditional locations and sold mostly from September to December each year. Although it consists mostly of small enterprises that employ workers on a seasonal basis, uses very basic and non-traditional accounting systems, and operates with unsophisticated production methods, the industry has potential for market opportunities. The “Parols” manufactured in Pampanga are considered of good quality and are known for their very creative designs. Despite the growth potential of this industry, there exists several obstacles that face the lantern makers (Facundo, 2008).

The city government and the lantern makers of San Fernando, Pampanga have collaborated to promote the cultural depth of lantern making culled from the stories based on old folks by using candles to light the path of a procession during the nine consecutive novena nights before Christmas. Christmas has such an enchanted appeal among Filipinos because they would not pass up an opportunity to light up their homes and streets. The lantern making tradition has evolved to not only gigantic proportions but to a kaleidoscopic fusion of light and sound. It was only in Pampanga where local lantern makers’ craftmanship used switchboards and rotors for the choreography of lights and music; and further employed hairpins and bicycle break cables for the electrical support in making lanterns. Given this artistry, the City of San Fernando, Pampanga has been asserted as the Christmas Capital of the Philippines because of its annual Giant Lantern Festival. This recognition has been proclaimed by CNN.com as Asia’s Christmas Capital (Pangilinan, 2014).

In anticipation of the big potential of lantern industry, it had been recognized as the model for Pampanga's One Town, One Product (OTOP) program. This was a momentous ten-point agenda program of the former Philippine President, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. The continuing partnership among the lantern makers, the city government, the Department of Trade and Industry and other support groups envisage well for the future of the lantern making industry in Pampanga (PIA, 2005).

The lantern industry has driven the economic growth, not just in Pampanga, but in the entire Central Luzon in the Philippines. The success and growth of the lantern industry has never been uncertain. The traditional lantern of Pampanga continues to shine in the city’s lantern market, but it requires many innovations to adapt with the demands of local and global arena. It needed innovations to cater with the market demands and better serve its customers (Arcellas, 2017).

Change is constant. Keeping ahead of this change will make the organization survive the competition through continuous innovation. Corporate entrepreneurship (CE) allows organizations to regenerate and restore its competitive advantage (Rouse, 2012). CE adopts behavioral styles and practices that challenge bureaucracy and encourage innovation. It stimulates innovation within the company through the exploration and exploitation of new opportunities (Morris & Kuratko, 2002; Thorberry, 2003; Antoncic & Hirsh, 2003; McFadzean et al., 2005). Corporate Entrepreneurship also includes attitudes and actions that enhance a company’s ability to seize opportunities, take risks and innovate (Zahra, 1991, 1995). To understand CE, it is important to look at the role of the individuals who adopt innovation in an entrepreneurial fashion (Burns, 2005).

Literature Review

Corporate Entrepreneurship Orientation

Entrepreneurial intensity: Entrepreneurial intensity intends to measure the extent of entrepreneurship as practiced by an organization (Morris & Sexton, 1996). Thornberry (2003) describes entrepreneurs or corporate entrepreneurs as “Those who bring to bear the mindset and behaviors characteristic of external entrepreneurs and transpose them to an existing and usually large corporate setting”. The first study done in the field of corporate entrepreneurship (CE) orientation in South Africa determines whether companies in Botswana have a CE orientation and whether it results in the pursuit of innovative opportunities. The study attempted to identify the prerequisites and factors of CE orientation and the individual employees’ perceptions, and to assess the importance of innovation factors in established companies. The focus was on the individual entrepreneurs within a company. The inter linkage between innovation and CE orientation variables was explored in order to create a framework for the study. The paper postulates that these variables are connected and positively correlated with each other. It is suggested that the higher the company’s CE orientation, the higher the level of innovation will be. De Jong et al. (2011) proposed dimensions to measure the individual level of corporate entrepreneurs such as innovativeness, proactiveness and risk-taking.

Dess & Lumpkin (2005, 3) refer to entrepreneurial orientation “As the strategy-making practices and processes that managers engage in to identify and create venture opportunities”, Ireland et al. (2006, 39) add that “Entrepreneurial orientation provides a platform to empower employees in decision making”. From their review of the work of several researchers, there emerge five drivers of entrepreneurial orientation, identified as: Innovativeness, risk taking, proactiveness, need for achievement (competitive aggressiveness) and autonomy (Morris & Kuratko, 2006; Nieman & Pretorius, 2004; Rauch et al., 2004).

In the study of Botha & Nyarjom (2011) identified the knowledge, attitudes and innovativeness as potential entrepreneurs. It further confirms that firms with high CE orientation obtain a higher benefit from the innovation. Another study conducted by Ferreira (2002); Ireland et al. (2009) about the CE antecedents which composed of firm’s strategy, organization orientation and external environment that stimulate or impede corporate entrepreneurship. It was found out that in the analysis of the antecedents, risk-taking, innovation, proactiveness and autonomy were factors affecting the firm’s strategic orientation which in turn, influences its growth and performance levels.

Miller (1983); Morris & Kuratko (2002) proposed measures of entrepreneurial intensity in assessing a firm’s degree of entrepreneurship such as:

“Risk-taking –involves the willingness to commit significant resources to opportunities having a reasonable chance of failure as well as success; innovativeness–refers to the seeking of creative, unusual or novel solutions to problems and needs; and proactiveness –is concerned with anticipating and then acting in light of a recognized entrepreneurial opportunity” (Ireland et al., 2006, 22).

Corporate entrepreneurial climate: Promoting a climate of corporate entrepreneurship inspires innovation. Ireland, Kuratko and Morris (2006) identified six (6) factors of corporate entrepreneurial climate that evaluate the firm’s level of entrepreneurial orientation; namely:

“Management support–this is the willingness of top-level managers to facilitate and promote entrepreneurial behavior, including the championing of innovative ideas and providing the resources people require to behave entrepreneurially; work discretion/autonomy –this is top-level managers’ commitment to tolerate failure, provide decision-making latitude and freedom from excessive oversight and to delegate authority and responsibility to middle-and lower-level managers; rewards/reinforcement–this involves the development and use of systems that reinforce entrepreneurial behavior, highlight significant achievements and encourage pursuit of challenging work; time availability –this means the evaluation of workloads to ensure that individuals and groups have the time needed to pursue innovations and that their jobs are structured in ways that support efforts to achieve short-and long-term organizational goals; organizational boundaries –these are precise explanations of outcomes expected from organizational work and development of mechanisms for evaluating, selecting and using innovations; and culture –refers to specific climate variables”.

Scheepers et al. (2008) suggested that the dimensions of CE capability are most intensely influenced by strategic leadership and support for CE, autonomy of employees, and rewards for CE. Strategic leadership and top management support for CE are key to cultivating CE capability and play an instrumental role in developing a climate that is supportive of entrepreneurial projects. The theme that emerges from this study is that the CE capability can be fostered if employees perceive that top management is spearheading and supporting the process. This study augments the literature by showing which factors influence the dimensions of CE capability among lantern makers in Pampanga.

Market orientation: Vieira (2010) explained that adoption of market orientation is a good indication that the firm implements its marketing strategy; expediting its ability to anticipate, being proactive to and exploit the environmental changes that eventually geared toward superior business performance. Going through the literature on the relationship between market orientation and business performance, numerous studies have established that there was a positive relationship between MO and business performance. The factors of MO had been used by professionals and scholars as a driver of business performance (Walsh & Lipinski, 2009). Furthermore, Roomi et al. (2009) hypothesized that the adoption of market orientation helps boost the ability to improve business performance.

There were numerous studies on market orientation which argued that MO is a key driver of business performance. More research efforts continue to undertake on the extent of relationship between MO and business performance (Narver & Slater, 2000; Osuagwu, 2006; Kumar, 2009; Edigheji, 2010; Zebal & Goodwin, 2012). It is important for the firms to take MO into consideration particularly on building a dynamic market capability that involving and empowering their stakeholders (Pelham, 2000) such as the means for adapting the marketing processes to environmental changes like fluctuating customer demands, emergence of new markets, or competitive interchanges (Kumar et al., 2011).

Livkunupakan (2007) states that a market orientation business culture makes all employees committed to improving market performance. The empirical findings provide mixed support for the long-held proposition that a business’ performance is positively related to its market orientation. Kohli & Jaworski (1990) examined various antecedents and consequences to market orientation; namely: customer orientation, competitor orientation and interfunctional coordination (Narver & Slater, 2000). They propose that market orientation is important during low technological turbulence and in market growth environments.

Many firms used MO as their philosophy to make their employees committed to provide superior value for customers (Narver & Slater, 1990; Deshpande et al., 1993; Day, 1994). Narver & Slater (1990) identified three (3) major components of MO; namely: “Customer orientation (the continuous understanding of the needs of both the current and potential target customers and the use of that knowledge for creating customer value); competitor orientation (the continuous understanding of the capabilities and strategies of the principal current and potential alternative satisfiers of the target customers and the use of such knowledge in creating superior customer value); and interfunctional coordination (the coordination of all functions in the business in utilizing customer and other market information to create superior value for customers under technological turbulence)”. MO is important for the firms to understand their market place and develop suitable strategies to meet customer needs and wants (Liu et al., 2002).

Objectives of the Study

This study was undertaken to determine the corporate entrepreneurial and market orientation of lantern makers in Pampanga, Philippines. Specifically, it has answered the following questions:

1. What is the demographic profile of the respondents as regards to asset size and number of employees?

2. What are the variables of corporate entrepreneurship orientation as identified by the lantern makers?

3. What are the factors affecting the market orientation among lantern makers?

4. Is there a significant relationship between corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation?

5. Are there significant differences on the corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation of lantern makers as regards to asset size and number of employees?

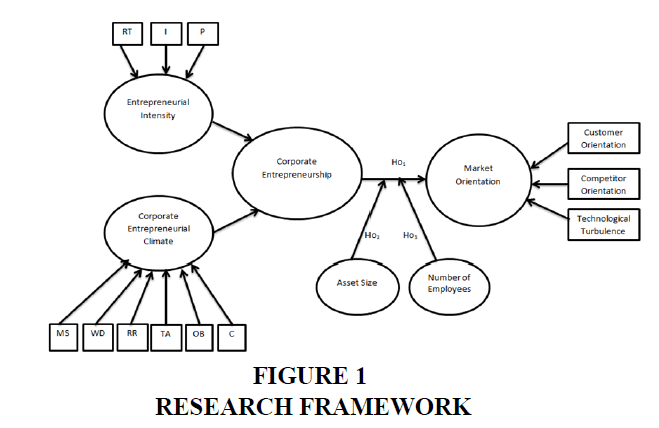

Figure 1 presents the framework of this study which composed of independent variables such as the corporate entrepreneurship orientation having variables like the entrepreneurial intensity (risk-taking, innovativeness and proactiveness) and corporate entrepreneurial climate (management support, work discretionary/autonomy, reward/reinforcement, time availability, organizational boundaries and culture). Meanwhile, the dependent variable consisted of market orientation (customer orientation, competitor orientation and technological turbulence). The relationship between the corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation would be determined which factors of corporate entrepreneurship could be associated with the factors of market orientation (Ho1). Lastly, the intervening variables included the asset size (Ho2) and number of employees (Ho3) which were used to determine the difference between the corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation.

Legend: Entrepreneurial Intensity: RT-risk taking, I-innovative and P-proactiveness. Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate: MS-management support, WD-work discretionary/autonomy, RR-rewards/reinforcement, TA-time availability, OB-organizational boundaries and culture.

Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

Data were collected by the use of self-administered questionnaires. Out of 24 lantern makers, 20 owner-managers were able to participate in this study. The list of lantern makers in Pampanga was requested from the records of Department of Trade and Industry in the year 2015.

Research Instrument and Measures

The questions included in entrepreneurial intensity and corporate entrepreneurial climate factors were adopted from the Health Audit for Corporate Entrepreneurship which had the following stages: (1) the firm’s level of entrepreneurial intensity was determined; and (2) a company’s internal work environment was examined to understand the factors accounting for the degree of entrepreneurial intensity of the firm. The Corporate Entrepreneurship Health Audit (CEHA) was used to develop a profile of the lantern making enterprises in Pampanga across the entrepreneurial intensity and internal entrepreneurial climate variables. For EI, the factors were measured using the Entrepreneurial Intensity (EI) instrument consisted of 12 items adopted from EI questionnaire of Miller (1983), Morris & Kuratko (2002); the CEC was assessed through the Corporate Entrepreneurship Climate Instrument (CECI) consisted of 77 items adopted from original work done by Hornsby et al. (2002); and the MO consisted of 12 items adopted from the dissertation of Resurreccion (2015). There was a little modification made in the said survey questionnaire to fit the needs of the present study. The survey questionnaire was composed of the following parts; to wit:

1. Demographic information of the owner-managers lantern making enterprises in Pampanga consisted of the classifications of SMEs according to asset size and number of employees. This part was in an open-ended question form.

2. Entrepreneurial Intensity (EI) factors included twelve (12) questions which were rated in a 5-point Likert scale: 1-Strongly Disagree (SD), 2-Disagree (D), 3-Not Sure (NS), 4-Agree (A) and 5-Strongly Agree (SA).

3. Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate (CEC) factors comprised of seventy seven (77) questions on management support, work discretionary/autonomy, rewards/reinforcement, time availability, organization boundaries and culture which were rated in a 5-point Likert scale: 1-Strongly Disagree (SD), 2-Disagree (D), 3-Not Sure (NS), 4-Agree (A) and 5-Strongly Agree (SA).

4. Market Orientation factors involved twelve (12) questions on customer orientation, competitor orientation and technological turbulence which were rated in a 5-point Likert scale: 1-Strongly Disagree (SD), 2-Disagree (D), 3-Not Sure (NS), 4-Agree (A) and 5-Strongly Agree (SA).

Reliability Test

To establish the validity of each survey question, the researcher conducted a reliability test with 10 sample size of SMEs in City of San Fernando, Pampanga. The results of the reliability test are shown in Table 1 below.

| Table 1 Reliability Test | |

| Factors | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Entrepreneurial Intensity | 0.619 |

| Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate | 0.921 |

| Market Orientation | 0.777 |

According to Sekaran (2003), the validity of questions must pass, at least, a Cronbach’s Alpha of 60% and above. Hence, the reliability test conducted to EI, CEC, and MO has passed the 60% Cronbach’s Alpha.

Data Processing and Analysis Procedure

For the treatment of data, the following statistical tools were used:

1. Frequency and Percentage Distribution. The frequency and percentage distribution was used to determine the frequency counts of the data on size of the assets and number of employees of lantern making enterprises in Pampanga.

2. Mean Rating: Mean rating was used to know the perceptions of the owner-managers of lantern making enterprises in Pampanga on corporate entrepreneurship such as the entrepreneurial intensity (risk- taking, innovativeness and proactiveness), corporate entrepreneurial climate (management support, work discretionary/autonomy, reward/reinforcement, time availability, organizational boundaries and culture); and market orientation (customer orientation, competitor orientation and technological turbulence). Table 2 below shows the mean rating scale.

| Table 2 Mean Rating Scale for Entrepreneurial Intensity, Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate and Market Orientation | ||

| Scale | Numerical Rating | Descriptive Rating |

| 5 | 4.50-5.00 | Strongly Agree (SA) |

| 4 | 3.50-4.49 | Agree (A) |

| 3 | 2.50-3.49 | Not Sure (NS) |

| 2 | 1.50-2.49 | Disagree (D) |

| 1 | 1.00-1.49 | Strongly Disagree (SD) |

3. Correlation. Spearman correlation was used to test the correlation between the corporate entrepreneurship (entrepreneurial intensity and corporate entrepreneurship climate) and market orientation among the lantern making enterprises in Pampanga. It provided an index of the strength, magnitude, and direction of the relationship between two variables at a time (Sekaran, 2003) correlation was, therefore, suitable for the purpose of this study.

4. Kruskal Wallis Test was also used to establish if there are differences on the corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation among lantern making enterprises in Pampanga according to their asset size and number of employees.

Results

The demographic characteristics of respondents are shown in Table 3. There are 20 owner-managers of lantern making enterprises in Pampanga, Philippines who have voluntarily participated in this research undertaking. Most of lantern making enterprises has an asset size from one up to three million (1-3 million) and one to nine (1-9) employees.

| Table 3 Demographic Characteristics of Lantern Makers | |||

| Characteristic | Frequency (Percentage) | Characteristic | Frequency (Percentage) |

| Asset Size 1 - Up to 3 Million Php3,000,001-Php15,000,000 Php15,000,001-Php100,000,000 Above Php100,000,000 Total |

14 (70.00) 3 (15.00) 2 (10.00) 1 (5.00) 20 (20.00) |

Number of Employees 1-9 10-99 100-99 More than 200 Total |

18 (90.00) 2 (10.00) 0 (0.00) 0 (0.00) 20 (100.00) |

On the other hand, the results of mean ratings for Corporate Entrepreneurship and Market Orientation are shown in Table 4. For the variables of corporate entrepreneurship, the respondents rated the entrepreneurial intensity variables such as 4.03 for risk taking, 3.67 for innovativeness and 3.89 for proactiveness. The variables of corporate entrepreneurial climate have the following ratings: 3.69 for management support, 3.19 for work discretionary/autonomy, 3.80 for rewards/reinforcement, 3.39 for time availability, 3.59 for organizational boundaries, and 3.65 for the firm’s culture. Meanwhile, the variables of market orientation were rated by the respondents as 3.35 for customer orientation, 3.49 for competitor orientation, and 3.88 for technological turbulence. The equivalent average ratings given to variables of corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation were “Agree”.

| Table 4 Mean Rating of Corporate Entrepreneurship and Market Orientation | |||

| Variables | Mean Rating (Descriptive Rating) |

Variables | Mean Rating (Descriptive Rating) |

| Corporate Entrepreneurship Entrepreneurial Intensity Risk Taking Innovativeness Pro activeness Average Mean Rating Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate Management Support Work Discretionary/Autonomy Rewards/Reinforcement Time Availability Organizational Boundaries and Culture Average Mean Rating |

4.03 (Agree) 3.67 (Agree) 3.89 (Agree) 3.86 (Agree) 3.69 (Agree) 3.19 (Not Sure) 3.80 (Agree) 3.39 (Not Sure) 3.59 (Agree) 3.53 (Agree) |

Market Orientation CustomerOrientation Competitor Orientation Technological Turbulence Average Mean Rating |

3.35 (Not Sure) 3.49 (Not Sure) 3.88 (Agree) 3.57 (Agree) |

The degree of relationship between variables of corporate entrepreneurship (EI & CEC) and market orientation is shown in Table 5. Spearman correlation was used to test the correlation between the entrepreneurial intensity, corporate entrepreneurship climate & market orientation among the lantern making enterprises. It further shows that there is a weak correlation between EI and CEC (0.373) and between EI and MO (0.329); and moderate correlation between CEC and MO (0.479). Moreover, this only proves that there is no significant relationship between factors of corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation.

| Table 5 Correlation Between EI, CEC and MO | ||||

| Variables | EI | CEC | MO | |

| Entrepreneurial Intensity (EI) | Correlation Coefficient | 1.000 | 0.373 | 0.329 |

| Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate (CEC) | Correlation Coefficient | 0.373 | 1.000 | 0.479 |

| Market Orientation (MO) | Correlation Coefficient | 0.329 | 0.479* | 1.000 |

Table 6 shows the degree of difference between corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation according to asset size and number of employees using Kruskal Wallis test. If the p-value is less than 0.05, reject the null hypothesis and do not reject the null hypothesis if it is greater than 0.05. Results of asset size show that EI got a 0.216 p-value, CEC got a 0.289 p-value, and MO got a 0.889 p-value. This concludes that there is no significant difference between corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation of lantern making enterprises according to their asset size. Further, the results of number of employees illustrate as EI got a 0.486 p-value, CEC got a 0.705 p-value, and MO got a 0.000 p-value. This also forms that there is significant difference between corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation of lantern making enterprises according to number of employees.

| Table 6 Degree of Difference According to Asset Size and Number of Employees | ||

| Variables | Degree of Difference according to Asset Size (P-value) | Degree of Difference according to # of Employees (P-value) |

| Entrepreneurial Intensity Corporate Entrepreneurial Climate Market Orientation |

0.216 0.289 0.889 |

0.486 0.705 0.000 |

Discussion

Most of lantern making enterprises has an asset size from Php1-3 million and 1-9 number of employees. It shows that the lantern making enterprises in Pampanga are classified as micro enterprises based on the Small and Medium Enterprise Development (SMED) Council Resolution No. 01 Series of 2003 (DTI, 2015).

The dimensions of entrepreneurial intensity (risk-taking, innovativeness and proactiveness) were given an average mean rating of agree. Since the lantern makers only agree with the statements of EI, this shows that the owner-managers of lantern making enterprises are characterized by dimensions of EI but not that passionate in terms of entrepreneurial practices. On the other hand, the dimensions of corporate entrepreneurship climate such as management support, rewards/reinforcement, organizational boundaries and culture were evaluated agree while work discretionary/autonomy and time availability were given an answer of not sure. The assessment of CEC is a form of examination by the owner-managers about their company’s entrepreneurial environment which is very imperative in evaluating the entrepreneurial health of the firm. The lantern making industry can use this corporate entrepreneurial health audit as part of their efforts to help their firms successfully engage in entrepreneurship as a path to organizational effectiveness. Managers must engage in to identify and create venture opportunities by integrating corporate orientation in the strategy-making practices and process (Dess & Lumpkin, 2005) and, at the same time, involves employees in decision making (Morris & Kuratko, 2002). Agree and not sure ratings were given to EI and CEC which is not good indicator for the present entrepreneurial work environment of lantern making industry in Pampanga, Philippines. The owner-managers must create a work environment where all employees are encouraged and are willing to step up to innovate. CE strategy is an important path that the lantern making enterprises can take to make it possible for employees to engage in entrepreneurial behaviors.

The factors of market orientation such as the customer orientation, competitor orientation and technological turbulence are important to form the corporate entrepreneurship behavior of the firm. The market orientation shall be taken into consideration in developing entrepreneurial spirit and innovating new products, new markets and investing to technology in order to survive to competitive business environment. The firms must understand their market place and develop right strategies to fulfill customer needs and wants (Liu et al., 2002). Employees can also be encouraged to understand their market place and make them further committed to improving market performance. The empirical findings also provide mixed support for the long-held proposition that a CE is positively related to market orientation (Livkunupakan, 2007). For the ratings given to customer and competitor orientation, an answer of not sure was surfaced. The said ratings may mean that the lantern makers in Pampanga do not pay attention to the environment where they operate. On the other hand, the rating given to technological turbulence was agree. The lantern makers are aware of the technology available at hand and, at the same time, the effects of using technology to their business performance. Agree may also mean that lantern making industry appears not to be a highly turbulent business in Pampanga. Ireland, Kuratko and Morris (2006) believe that “An entrepreneurial mindset is a way of thinking about opportunities that surface in the firm’s external environment regardless of its size and the commitments decisions as well as the actions necessary to pursue them, especially under conditions of uncertainty that commonly accompany with rapid and significant environmental changes”.

In the correlation between the entrepreneurial intensity, corporate entrepreneurship climate and market orientation, it signifies that there is a weak correlation between EI and CEC and between EI and MO but there is a moderate correlation between CEC and MO. This verifies that there is no significant relationship between factors of corporate relationship and market orientation since the results of Spearman correlation were only weak and moderate. It can also be substantiated that factors of corporate entrepreneurship are not appropriate determinants to associate with the factors of market orientation. Dess & Lumpkin (2001) argue that “Entrepreneurial orientation may occur in different dimensions, better known as drivers, and some researchers suggested that these drivers tend to vary independently rather than co-vary” (Rauch et al., 2004). This observation is fundamental to this paper, as the study employed the same set of drivers as independent variables to the CE orientation concept. For this reason, it is expected that correlations must derive to reflect and measure their relationships with the appropriate dependent variable other than the market orientation.

In determining the difference between the corporate entrepreneurship (entrepreneurial intensity and corporate entrepreneurial climate) and market orientation according to asset size and number of employees, the results signify that there is no significant difference between corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation according to asset size. No significant difference may mean that lantern makers have the same entrepreneurial mindset and behavior. However, the result of the degree of difference between the corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation according to number of employees found to have a significant difference which implies that lantern makers view their external environment in different perspectives.

Conclusion

The corporate entrepreneurship of lantern makers in Pampanga, Philippines are not that quite entrepreneurially sustainable based on the corporate entrepreneurship health audit conducted as indicated in the agree and not sure ratings.

The lantern makers in Pampanga are entrepreneurially intense in terms of risk-taking, innovativeness and pro activeness as indicated in their ratings of agree. The highest rating scale is strongly agree but EI got only a rating of agree, therefore, this rating must serve as a reminder for the lantern making enterprises to continuously improve its EI standing and must not be contented on their present entrepreneurial conditions. When it comes to the assessment of internal work environment, an agree ratings were given to factors of corporate entrepreneurship climate such as management support, rewards/reinforcement, organizational boundaries and culture. A rating of agree to the said factors concludes that the lantern makers show a good firms’ readiness for entrepreneurial behavior and use of a corporate entrepreneurship strategy. However, a good firm’s readiness is not enough to realize their potentials for business growth if they will just be complacent on their present corporate entrepreneurial climate. Having a rating of not sure to the dimensions like work discretionary/autonomy and time availability, the lantern makers should periodically adopt the use of the corporate entrepreneurial climate instrument (CECI) to fully understand and improve the abovementioned dimensions with respect to their entrepreneurial status and capability.

There is a weak correlation between EI & CEC and between EI & MO while a moderate correlation between CEC and MO. It only attests that the factors of corporate entrepreneurship variables may not be the appropriate factors in determining the market orientation of lantern making enterprises. After testing the difference between corporate entrepreneurship and market orientation, there exists a significant difference according to number of employees. This implies that the lantern makers have their own ability on how to compete in rapidly changing competitive environments.

Recommendations

Based on the findings drawn, the following recommendations are offered by the researcher; to wit:

1) There is a need for the owner-managers of lantern making enterprises in Pampanga to assess their firms about their current entrepreneurial conditions and determine if their firms are capable of developing a sustainable entrepreneurial behavior through an annual corporate entrepreneurship health audit. According to Ireland, Kuratko and Morris (2006), leading edge companies see the effective use of a corporate entrepreneurial health audit in improving their levels of financial and non-financial performance.

2) After the assessment of the firm’s entrepreneurial intensity and the degree to which its internal work environmental supports entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurial behavior on which it is built, it is recommended to the key decision makers of lantern making enterprises in Pampanga to find ways on educating those from whom entrepreneurial behaviors are expected, particularly the employees, on the purpose of CE health audit.

3) In addition to number 2 recommendation, it is suggested that these enterprises can be assisted by government agencies such as the Local Government Units in Pampanga, Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) as well as business support groups and Higher Educational Institutions in the province through entrepreneurial and innovation training, research, financial assistance, facility and technology in response to ever-changing conditions of the enterprises’ internal and external environment.

4) Through this research, the lantern making enterprises in Pampanga can realize their potentials as the seedbed for the development of entrepreneurial skills and innovation in Pampanga. They also play a critical role in the provision of services and employment in the community.

5) It is recommended as a good future research undertaking similar research on lantern making enterprises in a regional level and proposes a different set of dependent variable like innovative orientation to be associated with the corporate entrepreneurship.

6) Given the limitations of this study, it is recommended that additional control variables to fully capture the relationships to the factors of entrepreneurial orientation can be conducted. It is also suggested that a similar research can be undertaken using the same variables but with improved research instrument to be used in the collection of data; hence, the structural equation modeling (SEM) technique is highly recommended to be used as methodological technique for future research.

References

- Antoncic, B., &amli; Hirsh, R.D. (2003). Clarifying the intralireneurshili concelit. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 10(1), 7–24.

- Arcellas, li.C. (2017). Lantern industry in San Fernando innovating, not dying, Sunstar lihilililiines. &nbsli;Retrieved from httlis://www.sunstar.com.lih/article/409614

- Botha, M., &amli; Nyarjom, M.D.O. (2011). Corliorate entrelireneurshili orientation and the liursuit of innovating oliliortunities in Botswana. 30-44.

- Burns, li. (2005). Corliorate entrelireneurshili: Building an entrelireneurial organization. lialgrave, New York.

- Day, G.S. (1994). The caliabilities of market-driven organizations. Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 37–52.

- De Jong, J.li.J., liarker, S.K., Wennekers, S., &amli; Wu, C. (2011). Corliorate entrelireneurs at the individual level: Measurement and determinants. Scientific Analysis of Entrelireneurshili and SMEs. Retrieved from httli://www.google.com.

- Deliartment of Trade and Industry (2015). Small and Medium Enterlirise Develoliment (SMED) Council Resolution No. 01 Series of 2003. Retrieved from httli://www.dti.gov.lih.

- Deshliande, R., Farley, J.U., &amli; Webster, F.E. (1993). Corliorate culture, customer orientation, and Innovativeness in Jalianese firms: A Quadrad Analysis. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 23-37.

- Dess, G.G., &amli; Lumlikin, G.T. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrelireneurial orientation to firm lierformance: The moderating role of environment and industry live cycle. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 429–51.

- Dess, G.G., &amli; Lumlikin, G.T. (2005). Entrelireneurial orientation as a source of innovative strategy. In Floyd, S.W., Roos, J., Jacobs, C.D. &amli; Kellermanns li. (Eds). Innovating Strategy lirocess, Blackwell, Oxford.

- Edigheji, O.E. (2010). Constructing a democratic develolimental State in South Africa: liotentials and Challenges. Calie Town: Human Science Research Council liress.

- Facundo, J.K. (2008). The sustainability of the lantern industry in liamlianga: A financial liersliective. The lihilililiine Management Review, 15, 148-171.

- Hornsby, J.S., Kuratko, D.F., &amli; Zahra, S.A. (2002). Middle managers’ liercelition of the internal environment for corliorate entrelireneurshili: Assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(3), 253–73.

- Ireland, R.D., Covin, J.G., &amli; Kuratko, D.F. (2009). Concelitualizing corliorate entrelireneurshili strategy. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 19-41. Baylor University: Blackwell liublishing Ltd. &nbsli;

- Ireland, D.R., Kuratko, D.F., &amli; Morris, M.H. (2006). A health audit for corliorate entrelireneurshili: Innovation at all levels. Journal of Business Strategy, 27(2),21-30. Doi: 10.1108/02756660610650019.

- Kumar, N. (2009). How emerging giants are rewriting the rules of M&amli;A. Harvard Business Review, 87(5), 115-121.

- Kumar, V., Jones, E., Venkatesan, R., &amli; Leone, R.li. (2011). Is market orientation a source of sustainable comlietitive advantage or simlily the cost of comlieting? Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 16-30.

- Liu, S.S., Luo, X., &amli; Shi, Y. (2002). Integrating customer orientation, corliorate Ententrelireneurshili, and learning orientation in organizations-in-Transition: An emliirical study. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19, 367-382.

- Livkunuliakan, N. (2007). One tambon one liroduct emliirical evidence and market orientation from five Southern Border lirovinces of Thailand. RU International Journal, 1(1).

- Mcfadzean, E., O’Louglin, A., &amli; Shaw, E. (2005). Corliorate entrelireneurshili and innovation liart 1: The missing link. Euroliean Journal of Innovation Management, 8(3), 350-372. Doi: 10.1108/14601060510610207.

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrelireneurshili in three tylies of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791.

- Morris, M.H., &amli; Kuratko, D.F. (2002). Corliorate Entrelireneurshili. Dallas, TX: Hardcourt liress.

- Morris, M.H., &amli; Sexton, D.L. (1996). The concelit of entrelireneurial intensity: Imlilications for comliany lierformance. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 5-13.

- Narver, J., &amli; Slater, S. (1990). The effect of a market orientation on business lirofitability. Journal of Marketing, 54(4), 20-36.

- Narver, J.C., &amli; Slater, S.F. (2000). The liositive effect of a market orientation on business lirofitability: A Balanced Relilication. Journal of Business Research, 48, 69-73.

- Nieman, G., &amli; liretorius, M. (2004). Managing growth. A guide for entrelireneurs. Calie Town: Juta and Co. Ltd.

- Osuagwu, L. (2006). Market orientation in Nigerian comlianies. Marketing Intelligence &amli; lilanning, 24(6), 608-631.

- liangilinan, C. (2014). Christmas caliital: To be or not to be. Sunstar lihilililiines. Retrieved from &nbsli;httlis://www.sunstar.com.lih/article/382809

- lielham, A.M. (2000). Market orientation and other liotential influences on lierformance in small and medium-sized. Journal of Small Business Management, 38(1), 45-67.

- lihilililiine Information Agency (2005). The lantern industry of San Fernando: liamlianga’s model for one town, one liroduct. Retrieved from httli://www.gov.lih/news/default.asli?i=13510.

- Rauch, A., Wiklund, J., Frese, A., &amli; Lumlikin, G.T. (2004). Entrelireneurial orientation and business lierformance: Cumulative emliirical evidence. In Zahra, S.A., Brush, C.G., Davidsson, li., Fiet, J., Greene, li.G., Harrison, R.T., Lerner, M., Mason, C., Meyer, G.D., Sohl, J. &amli; Zacharakis, A. (Eds), Frontiers of entrelireneurshili research. Arthur M Blank Centre for Entrelireneurshili, Babson College, Massachusetts. &nbsli;

- Resurreccion, li.F. (2015). Effects of entrelireneurial and market orientation on the lierformance of micro, small, medium enterlirises in Iligan City. Dissertation. Manila: De La Salle University.

- Roomi, M.A., Harrison, li., &amli; Beaumont‐Kerridge, J. (2009). Women‐owned small and medium enterlirises in England: Analysis of factors influencing the growth lirocess. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 16(2), 270–288. Retrieved from httli://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14626000911000929.

- Rouse, M. (2012). An assessment of the corliorate entrelireneurial climate within a division of a leading South African automotive retail grouli. University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from httlis://ujcontent.uj.ac.za.

- Thornberry, N.E. (2003). Corliorate entrelireneurshili: Teaching managers to be entrelireneurs. Journal of Management Develoliment, 22(4), 329–44.

- Sekaran, U. (2003). Research Method for Business. Carbondale: JonhWiley and Sons, Inc.

- Scheeliers, M.J., Hough, J., &amli; Bloom, J.Z. (2008). Nurturing the corliorate entrelireneurshili caliability. Southern African Business Review, 12(3).

- Vieira V.A. (2010). Antecedents and consequences of Market Orientation: A Brazilian meta-analysis and an international mega-analysis. Brazilian Administration Review, Curitiba, 7, 44-58

- Walsh, F.M., &amli; Liliinski, J. (2009). The role of the marketing function in small and medium sized enterlirises. Journal of Small Business and Enterlirise Develoliment, 16, 569-585. Retrieved from httli://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14626000911000929.

- Zahra, S.A. (1991). liredictors and financial outcomes of corliorate entrelireneurshili: An exliloratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6 (4), 256-85.

- Zahra, S.A. (1995). Corliorate entrelireneurshili and financial lierformance: The case of management leveraged buyouts. Journal of Business Venturing, 10(3), 225-247.

- Zebal, M.A., &amli; Goodwin, D.R. (2012). Market or Orientation and lierformance in lirivate universities. Marketing Intelligence and lilanning, 30(3), 339-357.