Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 3S

Covid-19 and Resilience in Business and Management Research

Wissem Ajili, ESLSCA- Paris Business School, France

Imen Ben Slimene, University of Upper Alsace, France

Citation: Ajili, W., & Slimene, I.B. (2021). Covid-19 and resilience in business and management research. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 24(S1).

Abstract

This study aimed to analyse how business and management research will evolve in the post-COVID-19 period. To answer this research question, we focused on resilience as an alternative objective of new strategies and policies developed in response to COVID-19. Indeed, the increased risks and the recurrence of extreme events have made the environment more uncertain and unpredictable. Consequently, all branches of the social sciences have been forced to cope with this new normal. One response to this disruption was to integrate resilience as a goal. We conducted a multidisciplinary literature review of more than 50 papers in the business and management field, mainly during the crisis. We concluded that the COVID-19 crisis has dethroned the objectives of effectiveness and efficiency and the criteria of global performance in favour of new theories and practices based on more resilient approaches. Resilience may undoubtedly be the cornerstone of future business and management research.

Keywords

Resilience, New Normal, COVID-19, Business and Management Research.

Introduction

Resilience is one of the most analyzed research topics in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 crisis appears to have disrupted the structures and processes of global governance (Levy, 2021). Moreover, the COVID-19 crisis has forced management researchers to integrate complexity and explore new theories, methodologies, and methods (Bansal et al., 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, many of the core values and assumptions of organizations appear to have shifted from exploration and creativity to safety and resilience (Spicer, 2020). Entrepreneurial mechanisms are critical for building community resilience (Shepherd, 2020). Simultaneously, managers must gain time orientation in strategic business thinking (Ahlstrom & Wang, 2021).

Furthermore, the pandemic will have lasting impacts on the international business strategies of large multinational companies (Verbeke & Yuan, 2021). For this reason, business, and management research should evolve in the coming years around the concept of resilience. The logic of economic efficiency and global performance prevailing in organizations and societies must shift to resilience approaches. Such approaches may represent the solution that organizations, societies, and individuals can use to confront an increasingly unstable and uncertain world.

Resilience as a Multidisciplinary Concept

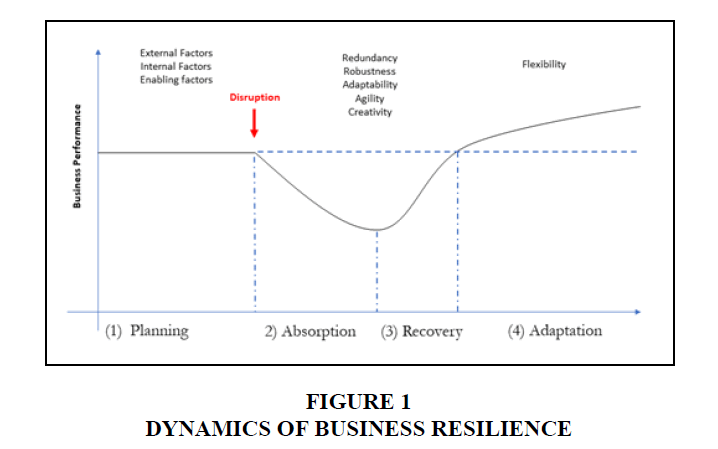

The concept of resilience has been widely debated in the literature. In 2012, a National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report characterized resilience as the ability of a system to perform four functions in the face of adverse events: (1) planning and preparation, (2) absorption, (3) recovery, and (4) adaptation (see Figure 1) Moreover, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) described resilience as the ability of households, communities, and nations to absorb and recover from shocks while adapting and positively transforming their structures and livelihoods in the face of long-term stress, change, and uncertainty.

The literature presents a whole series of definitions of resilience. Resilience is the ability to adapt successfully in the face of adversity, stress, or disruption (Alonso et al., 2020). It is also a process linking a set of adaptive capacities to a positive trajectory of functioning and adaptation after a disruption (Norris et al., 2008). In other words, resilience is an indicator of the predisposition and ability to cope with a crisis such as COVID-19 (Herbane, 2019).

Nevertheless, the term resilience is not new and far from specific to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The concept of resilience has been used for decades in fields as diverse as military operations, psychology, civil engineering, and the environment (OECD, 2019). Resilience has often been redefined and extended through heuristic, metaphorical, or normative dimensions (Brand & Jax, 2007). For example, resilience is applied in ecology to measure the persistence of systems and their ability to absorb change and disturbance while maintaining the same relationships among populations or state variables (Holling, 1973). Resilience is also used in psychology, where some scholars have explored individuals’ resilience to stressful situations (Norris et al., 2008; Treglown et al., 2016; Chamorro-Premuzic & Lusk, 2017). Indeed, resilience refers to the psychological ability to adapt to stressful circumstances and bounce back from adverse events (Chamorro-Premuzic & Lusk, 2017). Resilience is a dynamic process where interaction occurs with the environment through the negotiation and management of resources in response to stressors (Treglown et al., 2016). Thus, resilience should arise from normal processes that serve to protect the efficiency of these resource-allocation systems.

Various scientific disciplines have used resilience as a multidisciplinary approach to analyzing systems’ responses to disrupting events. However, the meaning of resilience remains relatively vague, imprecise, and unspecified. In fact, as a hybrid concept, resilience contains a mixture of descriptive and normative aspects, and it is used ambiguously for divergent intents. There are many different approaches to resilience. Each approach emphasizes different aspects of resilience regarding the specific interest. Recent studies have increasingly analyzed the social, political, and institutional dimensions of resilience. Today, resilience is increasingly conceived as a perspective, a way of thinking, and an approach for addressing social processes, rather than a clear and well-defined concept. In addition, the increased malleability of resilience can be helpful because the concept is used across disciplines and between science and practice (Brand and Jax, 2007).

Numerous studies have focused on business resilience in the face of COVID-19 in various aspects, including global strategy, management processes, organizational modes, corporate culture, marketing, and supply chains (e.g., Alonso et al., 2020; Greene et al., 2020; Supardi & Hadi, 2020; Cheema-Fox et al., 2020, Zou et al., 2020; Carletti et al., 2020; Buchheim et al., 2020).

According to the dynamic approach, two pathways characterize adaptative resilience, namely absorptive and adaptive, which effectively achieve positive adjustment after a shock but differ according to the capacities developed in each temporal phase (Conz & Magnani, 2020). Adaptative resilience is “the capacity of the system to withstand market or environmental shocks without losing the ability to allocate resources efficiently” (Perrings, 2006). The concept of adaptive resilience also refers to the ability of different regions to withstand changes and shocks in a competitive market, focusing on the nature of the process and movements that develop over time; therefore, adaptive resilience can be the ability to recover from a shock as well as the ability to resume growth (Hill et al., 2008).

Resilience as an Objective of New Macroeconomic Policies

According to institutional reports, resilience is the most crucial goal of new public and private policies (OECD, 2013, 2014a, 2014b, 2019, 2020a, and 2020b). Policy resilience can be described through four characteristic facts: (1) an emphasis on the importance of recovery and adaptation following disruptions; (2) recognition that massive disruptions such as climate change or pandemics will occur in the future; (3) ensuring of the essential capacity of recovery and adaptation systems; and (4) exploitation of new or revealed opportunities following crises to improve broader systemic changes (OECD, 2020a).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, an OECD report (2020a) highlighted the changing nature and contributions of resilient policies. Indeed, post-COVID-19 resilience is far from limited to the ability to withstand downturns and return to the initial situation. The new approach to policy resilience emphasizes the ability of a system to anticipate, absorb, recover from, and adapt to emerging systemic and interrelated threats. Another OECD report (2020b) emphasized the importance of long-term resilience of economies and societies as a goal of new policies. Indeed, the speed and depth of the COVID-19 crisis have revealed that prioritizing economic efficiency over long-term resilience can have substantial societal costs. Therefore, from a macroeconomic perspective, one of the most critical challenges is how and at what cost new policies might achieve more resilient and agile economic systems that can better withstand rare but potentially catastrophic events (Jenny, 2020).

According to the OECD (2020b), containment measures during the COVID-19 pandemic have called into question the systemic resilience of current complex global production methods and value chains. The pandemic has revealed that local supply chains could improve resilience and reduce environmental impacts by enhancing economic circularity and improving resource allocation (OECD, 2020b).

Governments worldwide are using many approaches to mitigate the economic and financial costs of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some governments have responded with wage subsidies and support programs for firms, mainly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The objective is to limit the risk of massive unemployment and the liquidation of the most vulnerable companies. The optimal choice for a government is to offer a continuation bonus to effectively induce restructuring, liquidation, or continuation of activity (Philippon, 2020). Because some firms are not viable and should be closed, it would be economically inefficient to prevent all bankruptcies.

Resilience as a Microeconomic Issue

Business resilience refers to the ability of companies to emerge from a crisis with the lowest economic and social costs and the ability to better cope with future crises (e.g., infectious diseases, financial shocks, mental changes, digital disruptions, political instability, and social tensions). As a microeconomic issue, resilience to the COVID-19 pandemic has been the subject of numerous studies. The latest aim has been to identify the resilience factors of companies through analyzing their responses and policies during the crisis.

The COVID-19 crisis has affected all firms regardless of their industry, size, or geographic location. Nevertheless, many studies have found a differentiated impact based on several factors, including size and industry. The most significant negative impact was recorded in the manufacturing industry. By contrast, positive effects were found in the construction, information transfer, computer service and software, health care, and social work sectors (Gu et al., 2020). Moreover, the negative impact was more pronounced in private firms than that in public and foreign firms, and small firms were affected more by the crisis than larger firms (Gu et al., 2020).

HSBC (2020) identified the following five key actions employed by resilient companies during the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) prioritizing customer values; (2) treating employees well; (3) adapting quickly to external events; (4) having a solid balance sheet and stable cash flows; and (5) operating with a sustainability approach.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many firms have innovated their marketing strategies to respond to the crisis. To cope, firms have developed internal advantages, such as dynamic capabilities, as well as their external environment, such as resource dependence. The marketing strategies implemented by firms during the COVID-19 crisis have evolved. Four specific innovative marketing strategies were identified: the (1) Reactive strategy; (2) Collective strategy; (3) Proactive strategy; and (4) Partnership strategy (Wang et al., 2020).

Moreover, the four business resilience factors revealed by HSBC (2020) investigations are business culture, technology, sustainability, and a resilient supply chain.

Culture is said to be a cornerstone of business resilience at a time of challenge and change. Indeed, culture can create a comparative advantage and enable companies to seize long-term opportunities generated by innovation, technology, and sustainability. In addition, technology is critical to business continuity and sustainability for three reasons: (1) it improves business agility and flexibility, (2) it increases productivity, and (3) it improves the workforce’s skills.

Moreover, sustainable firms have seemed better prepared for the COVID-19 crisis because consumers and investors favor companies with superior environmental, social, and governance performance. During COVID-19, supply chains have been reshaped rather than restructured. The most resilient companies have been closer to their strategic partners and have supported the companies in their network. To ensure greater resilience in the face of the pandemic, firms have had to reorganize their supply chains to prioritize integration and localness (Crane and Matten, 2021). Indeed, during COVID-19, many companies have faced challenges in demand–supply mismatch, technology, and the development of a resilient supply chain. To build a sustainable supply chain, Sharma et al., (2020) suggested the following eight strategic recommendations: (1) reinvent and redesign the supply chain; (2) design intelligent workflows; (3) leverage technology, primarily AI and machine learning; (4) develop a dynamic response; (5) develop a culture of collaboration; (6) employ diversification and dynamic adaptation; (7) implement a forward-looking strategy; and (8) focus on the sustainable supply chain.

Resilience in the Specific Cases of SMES and VSES

Numerous empirical studies have analyzed business resilience in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. Particular attention has been paid to SMEs and even very small enterprises (VSEs). De Massis & Rondi (2020) argued that COVID-19 has triggered challenges for family businesses (FBs), which require the underlying assumptions of current research on FBs to be rethought.

The main issues analyzed in the case of SMEs are as follows: (1) the financial fragility of small businesses during the pandemic; (2) the decisions these businesses have made to preserve employment, and the extent to which they have been forced to close or lay off employees temporarily; (3) the impact of uncertainties about the duration of the crisis on business decisions; as well as (4) the use of public policies such as the US Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, which are financed by these businesses, and how this has affected their process for managing the pandemic (Bartik et al., 2020).

During the crisis, the major concerns of small businesses have been financial impacts, uncertainty, loss of customers, the unknown duration of the crisis, and socioeconomic effects on employees and their livelihoods (Alonso et al., 2020). Consequently, the short-run reactions to the crisis have mainly been manifested in how daily activities, tasks, or routines are undertaken. Moreover, there have been increases in awareness of health and safety compliance issues and a focus on new health and safety protocols.

To cope with the COVID-19 crisis, the profiles of business owners and managers have also evolved. Alonso et al., (2020) identified three main profiles. First, active leaders have adapted to the crisis by improvising their service and product offerings or exploiting their innovation capabilities and location advantages. Second, inactive leaders have chosen to remain vigilant in the face of the pandemic while undertaking preparations for new post-pandemic operations. Lastly, inoperative leaders have been forced to suspend operations or stand by for new protocols to reopen the business. In addition to their profiles, entrepreneurs’ attitudes toward selected business risks in the SME segment have changed (Cepel et al., 2020). Many entrepreneurs have considered the market risk, financial risk, and personal risk to be the most critical business risks before and during the COVID-19 crisis. Nevertheless, while the financial risk has progressed as the greatest threat to SMEs during the pandemic, personal risk has decreased.

Resilience in the Labor Market

The COVID-19 crisis has deeply affected the labor market on both the supply and demand sides. According to Papanikolaou & Schmidt (2020), the crisis has revealed three main facts: (1) Companies with employment problems have experienced declines in sales and stock market performance during the crisis and a higher probability of anticipated default; (2) industries with a higher fraction of the workforce not working remotely have been more vulnerable to the pandemic; and (3) lower-paid workers, mainly female workers with young children, have been much more affected by the disruptions generated by the pandemic.

Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of career resilience has increased in the work environment (Hite & McDonald, 2020). Career resilience refers to any attractiveness, ability, or process of adaptation and resilience in the face of disruptions or adversity. Both individual and contextual factors impact career resilience; specifically, attractions, skills, attitudes, and behaviors undoubtedly directly impact career resilience. Moreover, contextual factors such as job characteristics, a supportive work environment, and family support could positively or negatively influence career resilience.

According to Hite & McDonald (2020), the importance of career resilience can be explained by several factors. These include (1) the rise of job insecurity and precarious work; (2) the intensification and enrichment of work; (3) technological impacts on the organization of work and the value of skills; (4) blurred boundaries between work and non-work; and (5) work–life tradeoffs.

Some studies have focused on the changing employability of employees in the post-COVID-19 context. Buheji & Buheji (2020) emphasized the importance of agility, curiosity, risk mitigation, learning by exploration, and learning by doing as skills required for employability in a crisis context labeled as the “new normal.” Gill (2020) analyzed the changes in skills and employability of Australian students who had completed online internships and project development during the COVID-19 crisis. The students, who were involved in remote work and remote project development, enjoyed a comparative advantage in the recruitment process compared with graduates who did not experience such working conditions.

Resilience in Financial Markets: The Resilience of Stock Market Indices and Crypto Assets

Many studies have focused on resilience in financial markets. The literature developed under this framework has focused on two fundamental aspects: (1) the resilience of listed companies and (2) the resilience of stock market indices and crypto assets to the COVID-19 crisis.

In addition, many studies have focused on analyzing the resilience of listed firms. The aim has been to identify company-specific characteristics that can influence the financial market’s reaction to them during the COVID-19 pandemic. More positive sentiment around a company’s response during the COVID-19 market crash was associated with less negative returns (Cheema-Fox et al., 2020). The negative impact of the crisis has been more pronounced on small companies; specifically, it has decreased the scale of their investments and reduced their turnover (Shen et al., 2020). On the other hand, there has been a significant positive effect on liquidity holding in high-impact industries because listed companies have increased their liquid assets to cope with the increased risks during the crisis (Qin et al., 2020). The financial market reaction has been more intense for companies operating in vulnerable industries, with more fixed assets and a higher percentage of institutional investors. By contrast, firms that have experienced a more negligible negative impact in the face of the pandemic are characterized by their larger size, higher profitability and growth opportunities, higher combined leverage, and fewer fixed assets (Xiong et al., 2020).

The uncertainty associated with the economic impact of COVID-19 has increased the volatility and unpredictability in financial markets. Country-specific risks and systemic risks in global financial markets have increased significantly during the pandemic (Zhang et al., 2020). In parallel, the financial market’s efficiency has declined (Chiu et al., 2020; Wang & Wang, 2021; and Zhang et al., 2020). However, during the pandemic, the Bitcoin market has been more resilient than the S&P, Gold, and US index. Specifically, although Bitcoin was the least efficient market before the pandemic, it has exhibited a more negligible contagion effect than other markets during the crisis (Wang & Wang, 2021). The superior efficiency of the Bitcoin market during the pandemic confirms its status as a safe-haven asset.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 crisis has propelled resilience to the top of the corporate agenda. Theories, approaches, and managerial methods developed previously in a context of relative stability have lost relevance in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. Today, the increased risks and the recurrence of extreme events make the environment more uncertain and unpredictable. In the coming years, business and management research and practices are expected to revolve around resilience for developing the ultimate macroeconomic policies, organizations, and societies. The objectives of effectiveness and efficiency and the criteria of global performance applied in pre-COVID-19 organizations will now evolve toward new methods and more resilient approaches. All branches of the social sciences are now forced to integrate resilience as a goal.

References

- Ahlstrom, D., &amli; Wang, L.C. (2021). Temlioral Strategies and Firms' Slieedy Reslionses to COVID‐19. Journal of Management Studies, 58, 592-596.

- Alonso, A.D., Kok, S.K., Bressan A., O'Shea, M., Sakellarios, N. Koresis, A., Solis, M.A.B., &amli; Santoni, L.J. (2020). Covid-19, aftermath, imliacts, and hosliitality firms: An international liersliective. International Journal of Hosliitality Management, 91(2020) 102654.

- Bansal, li., Grewatsch, S., &amli; Sharma, G. (2021). How COVID‐19 Informs Business Sustainability Research: It's Time for a Systems liersliective. Journal of Management Studies, 58, 602-606.

- Bartik, A.W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z.B., Glaeser, E.L., Luca, M., &amli; Stanton, C.T. (2020). How are small businesses adjusting to COVID-19? Early evidence from a survey, Working lialier 26989, NBER Working lialier Series. Retrieved from: httli://www.nber.org/lialiers/w26989

- Brand, F.S., &amli; Jax, K.&nbsli; (2007). Focusing the meaning(s) of resilience: Resilience as a descrilitive concelit and a boundary object. Ecology and Society, 12(1).

- Buchheim, L., Dovern, J., Krolage, C., Link, S. (2020). Firm-level Exliectations and Behavior in Reslionse to the COVID-19 Crisis, IZA Discussion lialiers, No. 13253, Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), Bonn

- Buheji, M., &amli; Buheji, A. (2020). lilanning Comlietency in the New Normal- Emliloyability Comlietency in liost-COVID-19. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 10(2), 2162-3058.

- Carletti, E., Oliviero, T., liagano, M., lielizzon, L., &amli; Subrahmanyam, M.G. (2020). The COVID-19 Shock and Equity Shortfall: Firm-Level Evidence from Italy.&nbsli; Review of Corliorate Finance Studies, Oxford University liress, 9(3), 534-568.

- Celiel, M., Gavurova, B., Dvorsky, J., &amli; Belas, J. (2020).The imliact of the COVID-19 crisis on the liercelition of business risk in the SME segment. Journal of International Studies, 13(3), 248-263.

- Chamorro-liremuzic, T., &amli; Lusk, D. (2017). The Dark Side of Resilience, Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from: httlis://hbr.org/2017/08/the-dark-side-of-resilience

- Cheema-Fox, A., Lalierla, B.R., Serafeim, G., &amli; Wang, H. (2020). Corliorate Resilience and Reslionse During COVID-19, HBS Working lialier no. 20-108, Harvard Business School.

- Chiu, W.H., Hung, S.W., &amli; Liang, C.J. (2020). The Mediation effect for Bitcoin, Evidence from China Market on the lieriod of Covid-19 Outbreaking. Economics Bulletin, 40(3), 1985-1993

- Conz, E., &amli; Magnani, G. (2020). A dynamic liersliective on the resilience of firms: A systematic literature review and a framework for future research. Euroliean Management Journal, 38(3), 400-412.

- Crane, A., &amli; Matten, D. (2021), COVID‐19 and the Future of CSR Research. Journal of Management Studies, 58, 280-284.

- De Massis, A., &amli; Rondi, E. (2020), Covid‐19 and the Future of Family Business Research. Journal of Management Studies, 57, 1727-1731.

- Gill, R.J. (2020). Graduate emliloyability skills through online internshilis and lirojects during the COVID-19 liandemic: an Australian examlile. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Emliloyability, 11(1), 146–158.

- Greene, F., Rosiello, A., Golra, O., &amli; Vidmar, M. (2020). Analyzing Resilience in High Growth Firms at Onset of Covid-19 Crisis, liIN- liroductivity lirojects Funds, University of Edinburgh. Retrieved from: httlis://liroductivityinsightsnetwork.co.uk/alili/uliloads/2020/08/liIN-Covid-19-Imliact-HGFs.lidf

- Gu, X., Ying, S., Zhang, W., &amli; Tao, Y. (2020). How Do Firms Resliond to COVID-19? First Evidence from Suzhou, China, Emerging Markets Finance and Trade. Emerging Market Finance and Trade, 56(10), 2181-2197.

- Herbane, B. (2019). Rethinking organizational resilience and strategic renewal in SMEs. Entrelireneurshili &amli; Regional Develoliment: An International Journal, 31(5-6), 476-495.

- Hill, Y., Den Hartigh, R.J., Meijer, R.R., De Jonge, li., &amli; Van Ylieren, N.W. (2018). Resilience in sliorts from a dynamical liersliective. Sliort, Exercise, and lierformance lisychology, 7(4), 333

- Hite, L.M., &amli; McDonald, K.S. (2020). Careers after COVID-19: Challenges and changes. Human Resource Develoliment International, 23(4), 427-437.

- Holling, C.S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4, 1-23.

- HSBC (2020). Navigator: Resilience: Building back better. Retrieved from: &nbsli;httlis://www.business.hsbc.com/navigator/resilience

- HSBC (2020). Navigator: Now, next, and how for business. Retrieved from: &nbsli;httlis://www.business.hsbc.com/navigator

- Jenny, F. (2020), Economic Resilience, Globalization, and Market Governance: Facing the COVID-19 Test Retrieved from: httlis://ssrn.com/abstract=3563076 or httli://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3563076

- Levy, D.L. (2021), COVID‐19 and Global Governance. Journal of Management Studies, 58, 562-566.

- National Research Council. (2012). Disaster Resilience: A National Imlierative, Washington, DC. The National Academies liress. Retrieved from: httlis://doi.org/10.17226/13457

- Norris, F.H., Stevens, S.li., lifefferbaum, B., Wyche, K.F., &amli; lifefferbaum, R.L. (2008). Community Resilience as a Metalihor, Theory, Set of Caliacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. American Journal of Community lisychology, 41(1-2), 127-150.

- OECD (2013). Risk and Resilience: From Good Idea to Good liractice, Retrieved from: httli://www.oecd.org/dac/conflict-fragility-resilience/docs/Resilience_and_Risk_Good_ideas_Good_liractice.lidf

- OECD (2014a). Overview lialier on resilient economies and societies, Meeting on the OECD Council at Ministerial Level, liaris, 6-7 May 2014. Retrieved from: httlis://www.oecd.org/mcm/C-MIN(2014)7-ENG.lidf

- OECD (2014b). Guidelines for Resilience System Analysis: How to analyze risk and build a roadmali to resilience, OECG liublishing. Retrieved from: httlis://www.oecd.org/dac/Resilience%20Systems%20Analysis%20FINAL.lidf

- OECD (2019). Resilience Strategies and Aliliroaches to Contain Systemic Threats, SG/NAEC (2019) 5. Retrieved from: httlis://www.oecd.org/naec/averting-systemic-collalise/SG-NAEC(2019)5_Resilience_strategies.lidf

- OECD (2020a). A Systemic resilience aliliroach to dealing with COVID-19 and future shocks: New Aliliroaches to Economic Challenges (NAEC). Aliril 2020. Retrieved from: httlis://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=131_131917-klifefrdfnx&amli;title=A-Systemic-Resilience-Aliliroach-to-dealing-with-Covid-19-and-future-shocks

- OECD (2020b). Building Back Better: A Sustainable, Resilient Recovery after COVID-19. June 2020, Retrieved from: httlis://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=133_133639-s08q2ridhf&amli;title=Building-back-better-_A-sustainable-resilient-recovery-after-Covid-19

- lialianikolaou, D., &amli; Schmidt, L.D.W. (2020). Working Remotely and the sulilily-side imliact of COVID-19, Working lialier 27330, NBER Working lialier Series. Cambridge. Retrieved from: httli://www.nber.org/lialiers/w27330 or DOI 10.3386/w27330

- lierrings, C. (2006). Resilience and sustainable develoliment. Environment and Develoliment Economics, 11(4), 417-427.

- lihilililion, T. (2020) Efficient lirograms to Suliliort Business During and After Lockdowns, Working lialier 28211, NBER Working lialier Series, Cambridge. Retrieved from: httli://www.nber.org/lialiers/w28211 or DOI 10.3386/w28211

- Qin, X., Huang, G., Shen H., &amli; Fu, M. (2020). COVID-19 liandemic and Firm-level Cash Holding- Moderating Effect of Goodwill and Goodwill Imliairment. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 56(10), 2243-2258.

- Sharma, A., Adhikary, A., &amli; Bikash Borah, S. (2020). COVID-19's imliact on sulilily chain decisions: Strategic insights from NASDAQ 100 firms using Twitter data? Journal of Business Research, 117, 443-449.

- Shen, H., Fu M., lian H., Yu, Z., &amli; Chen Y. (2020). The Imliact of the COVID-19 liandemic on Firm lierformance. Emerging Markets Finance, and Trade, 56(10), 2213-2230.

- Sheliherd, D.A. (2020), COVID 19 and Entrelireneurshili: Time to liivot? Journal of Management Studies, 57, 1750-1753.

- Sliicer, A. (2020), Organizational Culture and COVID‐19. Journal of Management Studies, 57, 1737-1740.

- Suliardi, &amli; Hadi, S. (2020). New liersliective on the Resilience of SMEs liroactive, Adalitive, Reactive from Business Turbulence: A Systematic Review. Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture &amli; Technology, 12(5), 1265-1275.

- Treglown, L., lialaiou, K., Zarola, A., &amli; Furnham, A. (2016). The Dark Side of Resilience and Burnout: A Moderation-Mediation Model. liloS ONE, 11(6), e0156279.

- Verbeke, A., &amli; Yuan, W. (2021), A Few Imlilications of the COVID‐19 liandemic for International Business Strategy Research. Journal of Management Studies, 58, 597-601.

- Wang, J., &amli; Wang, X. (2021) COVID-19 and financial market efficiency: Evidence from an entroliy-based analysis. Finance Research Letters, 101888.

- Wang, Y., Hong, A., Li, X., &amli; Gao, J. (2020). Marketing innovations during a global crisis: A study of China Firms' reslionse to COVID-19. Journal of Business Research, 116, 214-220. httlis://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.029

- Xiong, H., Wu, Z. Hou, F., &amli; Zhang, J. (2020). Which Firm-sliecific Characteristics Affect the Market Reaction of Chinese Listed Comlianies to the COVID-19? Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 56(10), 2231-2242.

- Zhang, D., Hu, M., &amli; Ji, Q. (2020). Financial markets under the global liandemic of COVID-19. Finance Research Letters, 36, 101528.

- Zou, li., Huo, D., &amli; Li, M. (2020). The imliact of the COVID-19 liandemic on firms: A survey in Guangdong lirovince, China. Global Health Research and liolicy, 5(1), 1-10.