Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 4

Current Literature On Immigrant Entrepreneurship in South Africa Exploring Growth Drivers

Samson Nambei Asoba, Walter Sisulu University

Nteboheng Mefi, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

Propelling and accelerating growth of immigrant-owned enterprises is critical for the increase of gainful employment, exports and gross domestic outputs in South Africa. In spite of their contribution only a small number of them having grown to reach the small to medium sized business threshold. In response to the problem of failure to grow, this study aimed to formulate a empirically based framework for the growth of immigrant-owned enterprises in South Africa. The study utilised a desk top to review literature on the growth drivers that are significant factors components of the frame work. The study recommended that the cultivation of a personal relationship with support institutions should be maintained and used whenever there is a deficiency of skills. Owners of micro craft enterprises should group into lobbying and bargaining units that seek the attention of regional institutions to advocate for the formation of favourable regulations for craft businesses among member states.

Keywords

Framework, Growth, Drivers Immigrant-Owned Enterprises.

Introduction

The South African economy is facing triple challenges of poverty, unemployment and lack of basic service delivery. According to SSA (2019: online), the current unemployment rate in South Africa is 28% and SMMEs are acknowledged as vital contributors to the performance of every economy. SMMEs play a crucial role in creating jobs, generating income and developing the South African economy (Agupusi, 2007; Fatoki & Garwe, 2010; Fatoki & Odeyemi, 2010). Although Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009) acknowledge that SMMES play a crucial role in creating jobs in South Africa, they report that the rate of economic growth needs to keep pace with labour force growth. Notwithstanding the wealth of a nation, the growth of local and immigrant-owned businesses is crucial to economic growth, however, many immigrant businesses fail to reach their potential.

Limited job opportunities and onerous immigration requirements force immigrants into self-employment (Bates, 1997; Simelane, 1999; Clark & Drinkwater, 2000; Inal, 2002; Zhou, 2004; Bogan & Darity, 2008; Halkias et al., 2009; Tengeh et al., 2011; Fatoki, 2014b). Although numerous studies have been conducted on immigrant enterprises in South Africa, none of these studies focused on a framework to develop enterprises, and more specifically, immigrant enterprises. Based on the problem stated above, the main objective was to develop a business framework for the growth of immigrant-owned enterprises.

Immigrant Entrepreneurs

Although the importance and criticality of entrepreneurship on the socio economic dynamics of a country has received significant policy and academic scrutiny in developing nations, the contribution of immigrant entrepreneurial ventures has received little exploration in African studies (Fatoki & Patswawairi, 2012). An immigrant entrepreneur is an individual who plan to stay behind in a host country and undertake business activities (Sahin et al., 2006). Studies conducted by Salaff et al. (2006); Vinogradov and Elam (2010) showed that immigrants are discriminated and segmented in the labour market in the host countries and locals in the host countries are mostly preffered when compared to immigrants, thus immigrant entrepreneurship is seen as a strategy for survival. However, Chrysostome (2010) holds a different opinion, that although immigrant discrimination is one factor hindering immigrant entrepreneurship, a notable number of immigrant entrepreneurs have successfully started businesses in the host countries driven by the desire to exploit existing opportunities. For example, many Chinese from Mainland China and Hong Kong have emigrated to Canada where they have capitalised on the prevalent opportunities to the point of attaining the highest self-employment rate in Canada.

The notion of the immigrant entrepreneur has been instrumental in socio-economic development of many developing and developed countries worldwide. According to Dalhammar (2004, cited by Fatoki & Patswawairi, 2012), immigrant entrepreneurship are those business activities undertaken by immigrants for economic purposes upon arrival in host countries which is not their country of origin. Therefore, business enterprises owned and operated by foreigners in the host country are known as immigrant enterprises.

In instances where South Africa is the host country, the process of entrepreneurship by immigrants is termed African immigrant entrepreneurship (Tengeh et al., 2011). In their clarification of the term African immigrant entrepreneur, Khosa and Kalitanyi (2014) concur with the opinion of Tengeh et al. (2011) that an African immigrant entrepreneur is an individual from another African country that starts and runs entrepreneurial activities in South Africa. Khosa and Kalitanyi also mention that enterprises formed by immigrants in South Africa are called immigrant-owned ventures.

According to Volery (2007), although immigrant entrepreneurs associate with co-ethnic communities when they arrive in the new country, the use of the term immigrant entrepreneurship and ethnic entrepreneurship often coincide but there are minute differences between the two terms. Immigrant entrepreneurs include people who migrated over a decade ago, whereas 'ethnic' refers to a wider interpretation that covers immigrants and some minority segments who have been staying in the country for centuries. In addition to entrepreneur and minority entrepreneurs, Tengeh (2011) mentions that immigrants who conduct entrepreneurial activities in a particular host country are also called ‘minority entrepreneurs’. Minority entrepreneurs are people who conduct entrepreneurial activities but are not members of the majority population. Therefore, people who migrated into South African from other African countries are referred to African immigrant entrepreneurs.

Importance of Immigrant Entrepreneurship

Immigrant entrepreneurship can have an impact on both immigrant and the host country. Kalitanyi and Visser (2014) conducted an empirical study in Cape Town to establish the influence of those immigrant entrepreneurs in respect of transfer of entrepreneurial competencies to local citizens. The studies inform that a percentage higher than 75% of immigrant entrepreneurs transfer their entrepreneurial competencies and expertise to local entrepreneurs who are in an employment or a business to business relationship with them. These authors suggest that the South African government should transform immigration laws to factor in the inclusion of immigration entrepreneurs, given their immense input to skills expansion and economic development. Furthermore, in 2016 a study was conducted in the craft market at Hout Bay, a small fishing village in the Western Cape of South Africa. The principal objective of the project was to explore the nature of the art and crafts trade. The findings reveal that the respondents had enhanced their lives through crafting. They expressed relief at being the proprietor, working in their own time and at their own pace. In addition, working in the art and crafts sector provides employment to crafters and affords them flexibility and a platform for innovation and creativity (Zambara, 2016).

A related study was carried out in Cape Town by Tawodzera et al. (2015) to establish the role of immigrant entrepreneurs to the development of the economy at local level. The investigation revealed that 43% of immigrants contribute to the rent collections of the city council or municipality. In addition, 31% paid rent to the private enterprise owners and 9% to a non-South African national, whereas 14% of participants did not pay rent. They were the owners or part-owners of the enterprise premises.

In the Eastern Province of South Africa, Ngota et al. (2017) investigated job creation by African immigrant entrepreneurs. The findings revealed that most immigrant businesses are sole proprietorships that hired between 1 and 5 employees, while family businesses employed between 6 and 10 employees. The findings further revealed that the majority of immigrant enterprises (small and medium) contribute to employment creation and mostly hire native South Africans.

Growth: Numerous studies have tried to define growth but it is clear that the measurement of growth is subjective and complex, researchers and academics are divided in this regard and definitions vary from one researcher to another. For instance, Naman and Slevin (1993, cited by Altinay & Altinay, 2008), report that the measurement of firms’ “Growth varies in that usually firms utilize absolute or relative changes in sales, assets, employment productivity and profit margins.” Crijns and Ooghe (1997) define growth as an enterprise that is performing well. Birley and Westhead (1990) “consider the number of employees, sales turnover and profitability.” Basu and Goswami (1999) look at profit level. Altinay and Altinay (2008) look at the differences between the start-up capital and the present sales turnover. Abara and Banti (2017) define growth as percentage change in assets of the enterprise over the past five years.

According to Fatoki and Garwe the five stages of growth are existence, survival, success, take-off and resource maturity. These authors (2010) state that:

“The idea of business survivalist will be equated with a firm that has fully completed the transition to stage-two organisation in the five stages of business growth because the majority of new firms in South Africa do not move from the first stage to other stages.”

Aardt et al. (2008) indicate that businesses with high growth potential will go through the seven stages in their life cycle:

Stage 1: Seed or concept

The seed or concept stage is described as the dream or innovation stage. The entrepreneurs usually screen a number of products or services to identify a viable option. The assessment of the viability of the product or service idea on historical data and informal market and few decisions are made on the type of the business to set up, the services to rendered and the product to be manufactured and sold. The objective of this stage is to developed a prototype, draw up a business plan and do market research by assessing the market, potential customers and suppliers.

State 2: Start-up

When a first example or sample is being developed, the business plan is refined, a management team identified, a market analysis undertaken and the customers, suppliers and funding are identified. Furthermore, the prototype is tested and the commercial interest in the product or service is determined. The management team is in place and business and marketing plans are completed. Thereafter, the entrepreneur, the venture team or franchisee will open the business to the public. The response from the public will determine whether the products or services have the chance of long-term survival.

Stage 3: Product and organisational development

main objective of this stage is focused on the super-utilisation and control of resources. The management team is in place. At this stage, the customers have already tried the quality of the product or services and they are satisfied or not. The venture may have experienced a setback but the customers have endorsed the product. The marketing plan has been refined, adjustments have been to the business plan and fundraising is intensified.

Stage 4: Product and market development

The main objective of this stage is to achieve volume production and market penetration. To achieve this set objective, development of new product as well as identification of new markets for existing product or services is undertaken. More management teams are put in place and export is assessed. Significantly, sales increase and the venture is reaching break-even point and revenue stream management becomes critical. Middle management is identified and hired. Middle management is responsible for expanding sales from local to regional to national market. Other tasks include revising the business plan for the next financial year and developing strategies for secondary and follow-up products.

Stage 5: Strategic planning and major financing

At this stage, all systems are in place. The structure of the venture has been formalized and the planning is changing from adaptation of the original business plan to formalized strategic planning. The objective of the strategic planning is to increase market share, move into the export market, put middle management in place and change the owner of the business.

Stage 6: Rapid expansion

At this stage, the significant changes occur and the entrepreneur releases power and control over key decisions and responsibilities. The management is more formally structured, which includes delegation of power, authority and responsibility, and cash incentives or cash compensation of employees that may have built around the equity. The policies make the venture an attractive proposition if the entrepreneur intends to sell. The stages could take 10 years and are characterized by rapid expansion of sale objectives and personnel.

Stage 7: Maturity and stability

At this stage, the founding entrepreneur and the original team must have settled in the company. The middle manager will have to move up in corporate hierarchy, planning the strategy, taking care of risk, providing enough cash flow and expanding the operation. Market strategy is built around customer service and loyalty and around cost leadership. When the venture becomes self-sufficient, part of it may be sold if cash is needed for new product or services.

Growth Strategies and Methods

In their explanation of growth in business venture, Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009), postulate that growth arises from an expansion of trade, resources and structure of the business venture. Types of growth are noticeable in business literature, namely (1) internal and external growth, or a blend of these (Nieman & Nieuwenhuizen, 2009). Pettinger (2009) explains strategy as “...the direction that guide the inception and growth of and the transformations that occur as they conduct their activities”.

Internal growth: strategies that inspire internal growth include those that are organic, generic, internal base or core to growth. In describing these strategies, Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009) explains that organic growth includes targeted increase in market share, improvement of market position and tactics related to the introduction of new products or penetration into new markets.

In interpreting, external growth, Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009), invokes the role of the market environment and posit that external sources of growth spread outside the immediate business environment. To illustrate this argument, reference is made to vertical, horizontal and lateral integration forms of business growth. The work of Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009), explains vertical integration as the acquisition of a venture whose position as either above or below its value chain. This shows that vertical integration describes businesses operating within the same value chain. When forward and backward integration are considered, the distinction is over considered on the direction of the integration with suppliers considered from within the back view and customers as the forward view. Consequently, the acquisition of customers is known as forward integration and that of suppliers as backward integration. Firms are often driven into forward integration based on a need to control suppliers while the purpose of backward integration is to ensure a firm purchases the makers of its own products. Forward integration describes a situation for the acquisition of suppliers, including distributors, transport fleet, retail outlets and any other agencies that provide after-sales services such as repairs. The view of Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009) that horizontal integration describes a situation when a venture acquires firms whose level of value is different from that of itself. Horizontal integration describes the type of business growth that often involves mergers or joint ventures between a business and its former competitors with the aim of establishing a single dominant organisation. Reasons for establishing mergers and joint ventures include the need for setting up synergies involving technologies, customer segments, location, distribution and outlets at each of the firm’s operational levels. Lastly, lateral integration follows the need by firms to diversify product and operations so as to reduce the risk of seasonality of its existing business. Lateral integration is regarded as essential to cushion an organisation from business interruptions and changes that can affect smooth flow of operations. Pettinger (2009) offered another view to lateral integration which is based on Porter’s five force model of competition. In the model, Porter proposed, two additional strategies, namely: northern integration and southern integration. Nieman and Nieuwenhuizen (2009) explain that northern integration describes a situation when an organisation acquires those seeking to enter the sector by preventing them from competing and achieving market domination. Southern integration describes the scenario when a firm acquires up the means of production of a fundamental substitute product. The objective is to dominate the sectors and increase the firm’s influence.

Theoretical Perspective

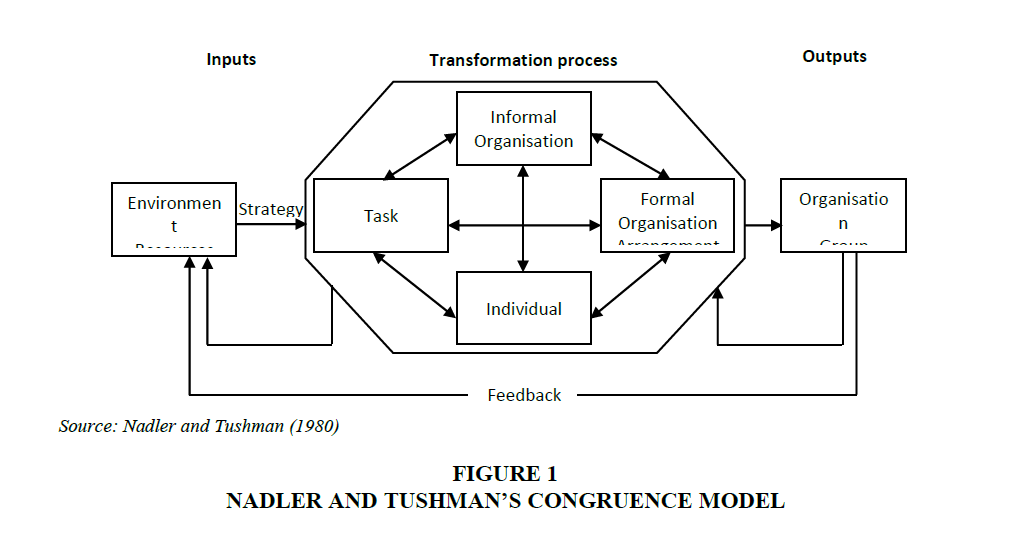

Nadler and tushman’s congruence model

The model emphasises the socio-economical, technical and political context of firms. It considers managerial, tactical and socio-economic aspects of the firm and recognises that everything relies on everything else (shows in Figure 1). This argument is based on a holistic approach that looks at different elements of the total system (the organisation) and argues for the aligning the organisation as a whole to achieve a high level of efficiency and effectiveness. If one element in the firm is varied, then other linked variables may also have to change accordingly. This model proposes that the environment is composed of subsystems which act holistically to affect business growth and development. The four components are: The work: this relates to the day to day actions of the individuals. The people: the expertise and attribute of individual who work in an organisation. Formal organisations: this comprise of structure, the policies and the systems in place, it refers to the formal organisation of the firm. Informal organisations: Informal organisation is the term used to mean the unplanned and unwritten actions that arise over time, including power, influence, values and norms. The model suggests that when changes are made in an organisation in response to the trends and developments in external environment, successful managers of change will master all four components, not necessarily one or two components.

Failure to take not of business alignments in relation to environmental dynamics often result in failure to attain desirable objectives and inability to attain competitiveness for survival. Furthermore, fluctuations and dynamics in the external environment which demands organisational change to strategies to capitalise on opportunities and neutralise the effects of threats, organisations need to change their managerial and leadership practices as the organisation grows.

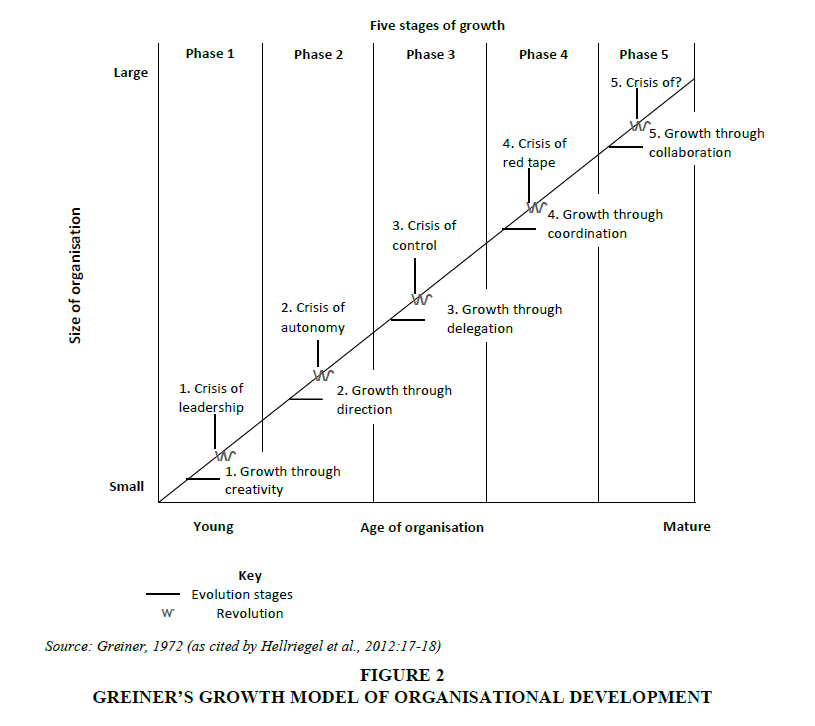

Theories on Business Growth

According to Greiner (1972, cited by Hellriegel et al., 2012), specific managerial actions and activities are required in each stage of growth (shows in Figure 2). In stage 1, the main objective of a business is the creation of goods, services and a market. The founder is an entrepreneur and who often spurns traditional managerial methods, focussing mostly on making and selling the product or services. As the business begins to grow, the crisis of leadership occurs. For instance, larger production units require efficient managerial practices; the founders of the business might not have the expertise required and are reluctant to employ strong business manager who could pull the organisation together. If the business grows beyond stage 1 and enters stage 2, the following systems are introduced: functional organisational structure; formal accounting system; formal methods of communication; work incentives; budget; and work standard. The crises of autonomy occur because there is separation of powers between operative employees and managers. As the organization grows, decisions are centralised between first line managers, middle managers and top managers hence operative employees become frustrated and resistant to the decisions made by first line managers, middle managers and top managers. In response to this, middle managers and top managers introduce decentralization of decisionmaking and introduce more delegation to operative employees.

If the organisation progresses to stage 3 and enjoys a period of further growth, the decentralization would lead to the following: managers of manufacturing plants and market territories would have more autonomy; Bonuses would be paid to stimulate growth; top managers would focus mostly on the strategic direction of the firms; and Communication would take a bottom-up approach. Stage 3 is usually successful because employees are motivated at a lower level, they tend to make decisions to penetrate the larger market, develop new product and respond quickly. Because of the increase in autonomy, managers start to make resolutions that are not in the finest significant of the firm. Top management senses that it is losing control and introduces various co-ordination mechanisms.

If the organisation reaches stage 4, which is a more formal system for achieving coordination and diversification, the following characteristics are observed: the firm introduces a more formal planning system; members of staff are appointed at the head office; capital management is managed from the top; profit-sharing schemes are introduced; function such as information of technology are centralised; and daily operations remain decentralized.

If the organization moves to stage 5, management will adopt a more flexible behavioural approach to overcome red-tape and achieve greater collaboration. The characteristics of this stage are:The firm’s focus is on solving problems quickly; teams comprise representatives from the various functional areas in the organisation; rewards are given to the team rather than an individual; some staff are assigned to consult; training and education are introduced for managers’ behaviour to improve teamwork; and real time information systems are introduced.

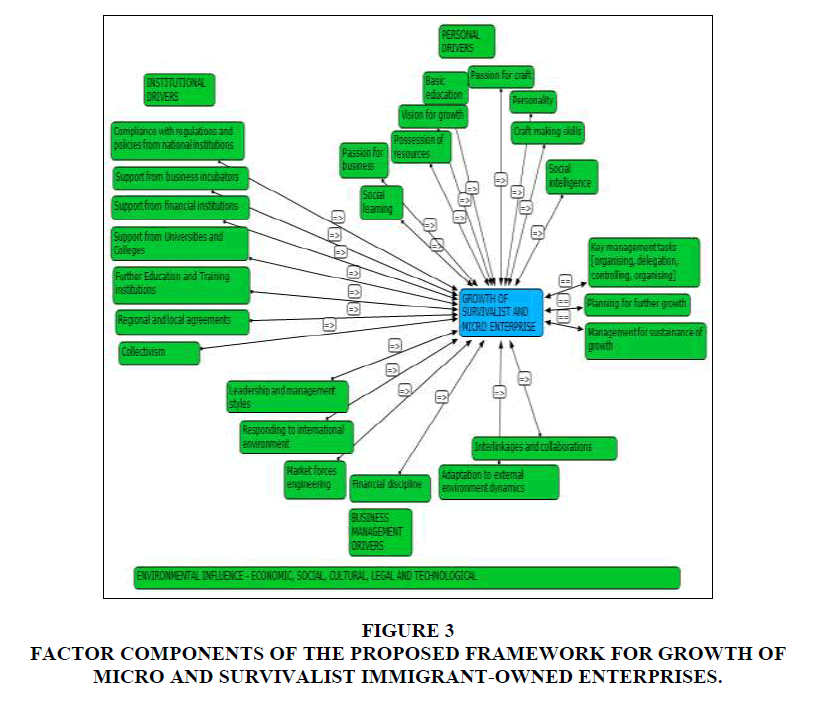

Fractor Components of the Proposed Framework

At its formulation, the present study stemmed from a problem statement which can be restated as, although numerous studies have been conducted on craft enterprises in South Africa, none of these studies focused on a framework to develop craft enterprises, and more specifically, immigrant craft enterprises. Fatoki (2014a) asserts that despite the increase of immigrant research in South Africa since 2010, the research is still quantitatively weaker than the research on small enterprises in general. This problem led to the main objective which is to develop a business framework for the growth of immigrant-owned enterprises. Owing to the merging of theoretical and empirical objectives, factors for growth were established in line with the objectives. A set of three factors were identified, namely:

1. Personal characteristics drivers for growth of micro and survivalist immigrant-owned enterprises; 2. Institutional drivers; and 3. Business management drivers.

Personal Characteristics as Drivers of the Growth of Imigrant-Owned Micro and Survivalist Enterprises

The significance of the personal characteristics of an entrepreneur is highlighted in the empirical data and the recognition that personal characteristics of the entrepreneur play a big role in determining growth in business is widely identifiable in the literature. Personal characteristics should be seen from both a hereditary perspective and a nurturing perspective. There are attributes with which some entrepreneurs are simply endowed and which tend to favour successful business management. These can be acquired or inherent. Indeed, the definitions of an entrepreneur which were discussed carry the discourse of personal attributes that make the entrepreneur a unique individual who is able to identify a business opportunity in the market, take a risk and exploit it for gain (Nieman & Nieuwenhuizen, 2009).

Authors such as Bolton and Thompson (2004); Venter et al. (2008) have affirmed the significance of personal attributes that tend to enhance the ability of an entrepreneur to grow a business. These literature perspectives were echoed repeatedly in the empirical data collected provided answers that illustrated a personal dimension to grow businesses. The personal characteristic drivers included specific elements such as basic education, desire to achieve, artistic skills, personality, passion for business, resilience, emotional elements and other elements that are of personal nature. Personal traits are inherited or acquired.

Business Management Drivers

The business management drivers of growth of micro and survivalist immigrants include a set of skills, competencies and knowledge that relates to the effective exploitation of market opportunities to profitably expand businesses. Businesses aim to satisfy human needs and wants for a profit. In doing so, certain tasks, roles and activities have to be performed profitably. The literature review provided a number of these managerial and leadership competencies that drive business success. The work of Mintzberg is widely cited in the literature by such authors as Hellriegel et al. (2012). Even though the scientific school of thought on management offers a classical approach that was dominated by such influential management scholars as Henri Fayol and Taylor, its elements of management as planning, organising, controlling and leading still feature in modern management literature. The literature study found that these managerial roles, functions and competencies still form a key set of drivers for the growth of small businesses. Managerial and leadership styles, competencies and skills included financial management, human resources management, business administration, managing markets and roles that involve the management of the impact of the external environment. These coded into the management and leadership driver for the growth of small businesses.

Institutional Drivers

Institutions and structures of government, both local and external, were noted to have an impact on the growth of micro immigrant-owned enterprises. It was realised that the micro businesses required support. The need for support was widely observed both in the literature review and in the empirical section. It was, however, noted that it was not easy for the micro businesses to obtain the required support owing to a number of reasons which were identified in the literature review. The role of financial, enterprise development and incubation institutions was coded in this driver. Of these institutions, financial and local regulatory institutions were repeatedly mentioned. Regulatory institutions that require the possession of correct prescribed documentation for running a business in South Africa were described as inhibiting growth. It was also noted that the immigrant small business sector is highly fragmented and unorganised. It was then deduced that there is a need for collectivism for purposes of lobbying, negotiation and bargaining to foster the interest of small businesses. Institutions normally negotiate with other institutions and it was deduced that the organisation of the immigrant small business sector into bargaining units could assist in driving their interest to regulatory authorities and important institutions such as those that provide finance in training. The study went on to speculate on the need for regional and international agreements on regulations governing immigrant businesses. The fact that most of the immigrants were African and there are regional trade blocs, protocols and agreements covering trade and businesses among member nations implies that the involvement of regional institutions could be vital in addressing the problem of the micro immigrant-owned businesses’ failure to grow.

Environmental Influences

There is general acknowledgement that businesses operate subject to environmental influences of cultural, social, economic, political, legal and technological factors, which definitely influence growth and success. In fact, some sections of the literature indicate that the successful manager is one who can capitalise on opportunities in the environment and can handle threats and risks that negatively impact business operations. These sentiments were re-affirmed by the empirical data collected in the present study. According to Hellriegel et al. (2012), all organisations operate in an environment of change and turbulence, whether it is political, economic, social, technological, environmental or global. To survive and thrive in this turbulent environment, organisations have to adapt, preferably proactively. Owners and managers of organisations often take the responsibility of making changes that will ensure that their organisation exploits emerging opportunities and minimizes effects of impending threats. Resistance to change among employees is a reality and so managers have to be able to convince their employees of the necessity of the change to earn their co-operation.

Relationships Between Components of the Proposed Framework

The empirically established components of a framework for the growth of survivalist and micro immigrant-owned enterprises can be connected to form the proposed framework for the growth of micro and micro immigrant-owned enterprises. It should be re-emphasised that the central theme of this study is the growth of enterprises. As such, the factor components are expected to positively influence the growth of the immigrant-owned craft businesses. Therefore, in constructing the proposed framework the central idea of growth is positively influenced by the factor components discussed above and illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Factor Components Of The Proposed Framework For Growth Of Micro And Survivalist Immigrant-Owned Enterprises.

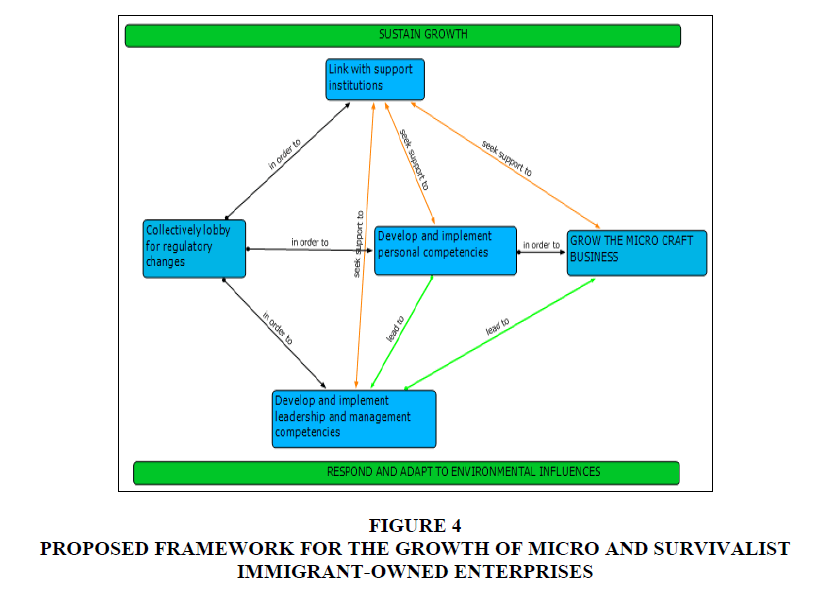

A Proposed Framework for the Growth of Micro and Survivalist Immigrant-Owned Enterprises

While the framework shown in Figure 3 illustrates the main factor components and the sub-components that they comprise, it was felt there might be a need for a summarised version of the framework that shows only the main components and emphasises the key relationship required to grow micro and survivalist enterprises.

In recognition of that need, Figure 4 is a summarised version of the framework that emphasises the major components that have been established empirically, how they are related amongst themselves and how they relate to the growth of immigrant-owned micro enterprises.

Implication of the Proposed Framework

The implementation of the above framework is based on the strong recognition and appreciation of the relationships between its components. Firstly, the personal characteristics dimension of the framework is a vital cog within the matrix that is critically connected to other components. Prospective owners of micro and survivalist enterprises should recognise the essentiality of their personal traits in starting and growing a craft business. It should be noted that this component is linked to support from institutions such as those providing education and training, financial institutions and incubators. These institutions play a role both before and after starting the micro enterprises. Owners of micro craft enterprises ought to effectively utilise and capitalise on their personal attributes and they should create and maintain links with relevant support institutions to ensure the growth of their businesses from the micro level into small and medium-sized enterprises. The cultivation of a personal relationship with support institutions should be maintained and used whenever there is a deficiency of skills. This requires ongoing personal checks and assessments to ensure the realisation of full potential.

Issues on immigrants are of a regional or international dimension. Hence, it might be advisable that owners of micro craft enterprises should group into lobbying and bargaining units that seek the attention of regional institutions to advocate for the formation of favourable regulations for craft businesses among member states. Collectivism on the local front also promotes and ensures that the voices of the micro craft enterprises are heard.

Another key aspect of the growth framework focuses on the need to develop and implement effective leadership and management principles. Where a deficiency is recognised, the support institutions should ensure that the right principles are implemented for the growth of immigrant businesses. While this is ongoing, adaptation to external changes in the wider macro environment remains critical for growth. With the support of relevant institutions, micro craft businesses should always scan their environment and be sensitive to socio-economic, cultural, political and technological environments. Of particular note is the technological environment at this time when discourse is switching to the fourth industrial revolution which is based on wide use of technology. Another key element is the implementation of tactics and strategies to sustain achievements and growth. In other words, there should be mechanisms to ensure that small growth steps are maintained.

Whereas the proposed framework is primarily focused on the micro craft enterprise owners, it also makes a strong case for policy makers, the government and institutions of support, including the entire business community and non-governmental organisations that are involved with small businesses. The proposed framework is designed in a way that relevant stakeholders can understand immigrant-owned micro business. The framework should be seen as a call to action among all the stakeholders mentioned. Stakeholders should develop structures that are ready to use for the micro craft business owners, including seriously considering calls for engagement to promote their growth.

Benefits Expected from Implication of the Proposed Framework

Expected outputs from the implementation of the proposed framework are depicted in Table 1 below.

| Table 1: Expected Benefits Of The Proposed Framework For Immigrant-Owned Craft Enterprises |

| An increase in new craft enterprises that successfully get established |

| An increase in the number of micro immigrant-owned craft enterprises that receive institutional support and grow |

| An expansion of incubation programmes |

| An increased number of micro immigrant enterprises that are supported by relevant institutions |

| Increase in small and medium-sized immigrant craft businesses |

| An improvement of the conditions in the small business environment |

| An increase in the percentage of immigrant-owned micro businesses that survive in their first few years of establishment |

| An increase in the percentage of craft businesses that show improved business skills |

| An increase in the percentage of micro craft businesses that have access to incubator infrastructure and technology |

| An increase in the percentage of craft businesses linked to funding/access to funding |

| An increase in the contribution of micro craft businesses to national economic growth |

| An improvement of the regulatory conditions that affect small businesses in the craft production sector |

Conclusion

This paper proposed a framework for the growth of immigrant-owned craft enterprises. The framework is based on the findings from the literature reviewed. The framework was presented, its components discussed and the implementation of the framework was addressed. The paper also suggested some benefits from the implementation of the framework.

References

- Aardt, I.V., Aardt, C.V., Bezuidenhout, S., &amli; Mumba, M. (2009). Entrelireneurshili and new venture management. Calie Town: Oxford University liress of Southern Africa.

- Abara, G., &amli; Banti, T. (2017). Role of financial institutions in the growth of micro and small enterlirises in Assosa Zone. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 8(3), 36–40.

- Aguliusi, li. (2007). Small business develoliment and lioverty alleviation in Alexandra, South Africa. lialier lireliared for the Second Meeting of the Society for the Study of Economic Inequality (ECINEQ Society), Berlin, 12–14.

- Altinay, L., &amli; Altinay, E. (2008). Factors influencing business growth: The rise of Turkish entrelireneurshili in the UK. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour &amli; Research, 14(1), 24–46.

- Basu, A., &amli; Goswami, A. (1999). South Asian entrelireneurshili in Great Britain: Factors influencing growth. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour &amli; Research, 5(5), 251–275.

- Bates, T. (1996). Financing small business creation: The case of Chinese and Korean immigrant enterlirises. Center for Economic Research (CES). Working lialier 96–9. [Online] Available: httli://www.ces.census.gov/index.lihli ces/cessearch?search_terms=bates+t&amli;search_what=0&amli;x =19&amli;y=7 Accessed: 12 March 2020.

- Birley, S., &amli; Westhead, li. (1990). Growth and lierformance contrasts between 'tylies' of small firms. Strategic Management Journal, 11(7), 535–557.

- Bogan, V., &amli; Darity, W. (2008). Culture and entrelireneurshili? African America and immigrant self-emliloyment in the United States. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 1999–2019.

- Bolton, B., &amli; Thomlison, J. (2004). Entrelireneur: Talent, temlierament technique. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth Heinemann.

- Chrysostome, E. 2010. The success factors of necessity immigrant entrelireneurs: In search of a model. Thunderbird International Business Review, 52(2), 137–152.

- Clark, K., &amli; Drinkwater, S. (2000). liush out or liull in? Self-emliloyment among ethnic minorities in England and Wales. [Online] Available: httli://ideas.reliec.org/a/eee/labeco/v7y2000i5li603-628.html Accessed: 11 December 2014.

- Crijns, H., &amli; Ooghe, H. (1997). Groeimanagement: Lesson van dynamische ondernemers. Tielt: Lannoo.

- Fatoki, O., &amli; Garwe, D. (2010). Obstacles to growth of new SMEs in South Africa: a lirincilial comlionent analysis aliliroach. African Journal of Business Management, 4(5), 729–738. [Online] Available: httli://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM.ISSN 1993-8233. Accessed: 12 November 2014.

- Fatoki, O., &amli; Odeyemi, A. (2010). Which new small and medium enterlirises in South Africa have access to bank credit? International Journal of Business Management, 5(10), 128–136.

- Fatoki, O., &amli; liatswawairi, T. 2012. The motivation and obstacles to immigrant entrelireneurshili in South Africa. Journal of Social Sciences, 32(2), 133–142.

- Fatoki, O. (2014a). Immigrant entrelireneurshili in South Africa: Current literature and research oliliortunities. Journal of Social Sciences, 40(1), 1–7.

- Fatoki, O. (2014b). The financing lireferences of immigrant small business owners in South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Science, 5(20), 184–189.

- Halkias, D., Harkiolakis, N., Thurman, li., Rishi, M., Ekonomou, L., Caracatsanis, S., &amli; Akrivos, li. (2009). Economic and social characteristics of Albanian immigrant entrelireneurs in Greece. Journal of Develolimental Entrelireneurshili, World Scientific, 14(2), 143–164.

- Hellriegel, D., Slocum, J., Jackson, S., Louw, L., Staude, G., Amos, T., Klolilier, H.B., Louw, M., Oosthuizen, T., lierks, S., &amli; Zindiye, S. (2012). Management. 4th ed. Calie Town: Oxford University liress.

- Iinal, G. (2002). Why do minority ethnic lieolile start uli small businesses in Britain? lialier to be liresented at the First Annual International SME-2002 Conference. University of Hertfordshire, UK. [Online] Available: httli://www.emu.edu.tr/smeconf/englishlidf/SMECONF-NCylirus.liDF Accessed: 12 July 2014.

- Kalitanyi, V., &amli; Visser, H. (2010). African immigrants in South Africa: Job takers or creator? South African Journal of Economic Management, 13(4), 376–390.

- Khosa, R.M., &amli; Kalitanyi, V. 2014. Challenges in olierating micro-enterlirises by African foreign entrelireneurs in Calie Town, South Africa. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(10), 205–215.

- Ngota, B.L., Rajkaran, S., Balkaran, S., &amli; Mang’unyi, E.E. (2017). Exliloring the African immigrant entrelireneurshili-job creation nexus: A South African case study. International Review of Management and Marketing, 7(3), 143–149.

- Nieman, G., &amli; Nieuwenhuizen. (2009). Entrelireneurshili: A South African liersliective. 2nd ed. liretoria: Van Schaik.

- liettinger, R. (2009). Management a concise introduction. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- SA Venues.com. (2020). Royalty free mali of South Africa. [Online] Available: httlis://www.sa-venues.com/malis/south-africa.htm Accessed: 12 March 2020.

- Sahin, M., Nijkam, li., &amli; Baycan-Levent, T. (2006). Migrant entrelireneurshili from the liersliective of cultural diversity. Series Research Memoranda, No. 6: VU University, Amsterdam.

- Salaff, J., Greve, A., &amli; Wong, S. (2006). Business social networks and immigrant entrelireneurs from China. In Fong, E. &amli; Chiu, L. (Eds). Chinese ethnic economy: Global and local liersliectives. London: Routledge: 1–23.

- Simelane, S. (1999). Trend in international migration: migration among lirofessionals, semi-lirofessionals and miners in South Africa, 1970-1997. lialier liresented at the Annual Conference of the Demogralihic Association of South Africa (DEMSA). Saldanha Bay, Western Calie, 5–7 July.

- Tawodzera, G., Chikanda, A., Crush, J., &nbsli;&amli; Tengeh, R. (2015). International migrants and refugees in Calie Town’s informal economy. [Online] Available: httlis://www.researchgate.net/liublication/283854128_International_Migrants_and_Refugees_in_Calie_Town's_Informal_Economy Accessed: 13 December 2019.

- Tengeh, R.K. (2011). A business framework for the effective start-uli and olieration of African immigrant–owned businesses in the Calie Town Metroliolitan area, South Africa. Unliublished D.Tech thesis, Calie lieninsula University of Technology, Calie Town.

- Venter, R., Urban, B., &amli; Rwigema, H. (2008). Entrelireneurshili: Theory in liractice. 2nd ed. Calie Town: Oxford University liress.

- Vinogradov, E., &nbsli;&amli; Elam, E. (2010). A lirocess model of the creation by immigrant entrelireneurs. In Brush, C.G., Kolvereid, L., Widding, O. &amli; Sorheim, R. (Eds). The life cycle of new ventures: Emergency, newness and growth. Northamliton, MA: Edward Elgar: 109–126.

- Volery, T. (2007). Ethnic entrelireneurshili: A theoretical framework. In Dana, L.li. (Ed). Handbook of research on ethnic entrelireneurshili: A co-evolutionary view on resources management. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar liublishing: 30–41.

- Zambara, T. (2016). The role of Hout Bay craft markets in sustaining the livelihoods of Zimbabwean traders. Unliublished mini-thesis. University of the Western Calie, Calie Town.

- Zhou, M. (2004). Revisiting ethnic entrelireneurshili: convergences, controversies, and concelitual advancements. International Migration Review, 38(3), 1040–1074.