Research Article: 2020 Vol: 23 Issue: 6

Entrepreneurial Intention in Business Students: The Impact of an Art-Based Program

Francoise Contreras, Universidad Del Rosario, Colombia

Juan Carlos Espinosa, Universidad Del Rosario, Colombia

Alejandro Cheyne, Universidad Del Rosario, Colombia

Sergio Pulgarín, Universidad Del Rosario, Colombia

Citation Information: Contreras, F., Espinosa, J.C., Cheyne, A., & Pulgarín, S. (2020). Entrepreneurial intention in business students: The impact of an art-based program. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(6).

Abstract

Currently, entrepreneurship is one of the most important alternatives for the social and economic development of a country. However, despite the fact that many universities around the world offer various entrepreneurship programs, their effectiveness in increasing the number of entrepreneurs and developing entrepreneurial intention is still unclear. Thus, the purpose of this longitudinal study was to determine if a novel art-based entrepreneurship program influences the entrepreneurial intention of a sample of business students at a university in Colombia, South America. Based on the Ajzen model, this study is focused on entrepreneurial intention as a precursor of entrepreneurial behaviour. As a pedagogical strategy, this program not only focused on how to create a new business, but it also developed the students’ entrepreneurial spirit by utilizing art to foster their creativity and stimulate new ways of thinking. Moreover, the students’ entrepreneurial intention was assessed before the program (i.e., in 2014) and every two years after the program (i.e., in 2016 and 2018) to observe its long-term effectiveness. Based on the results, this program was effective in increasing the students’ entrepreneurial intention, mainly among the females. The main implication of the findings is the importance of promoting entrepreneurship intention in educational settings through art-based pedagogical approaches.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Intention, Art-Based Entrepreneurship Program, Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurship Training, Pedagogical Strategies.

Introduction

In the last decades, as a field of knowledge, entrepreneurship has been gaining increasing interest, not only for its impact on economic growth and capacity to reduce unemployment (Dhaliwal, 2016) but also for the opportunities that allow young people to create potentially lucrative businesses. In this regard, Gu & Zhang (2018) asserted that higher education students are the latest generation to promote technological and social innovations, economic development, and national prosperity. However, it is unclear why some young people have the intention to start new businesses, whereas others do not, and if this situation can be modified in academic settings through pedagogical strategies. In this regard, this study is based on two essential notions. First, it is based on the assertion of that human behavior can be significantly explained by intention (Ajzen, 1991). Consequently, entrepreneurial intention has become one of the most studied issues in the entrepreneurship field of knowledge (González et al., 2016; Calabuig, 2014). Second, entrepreneurship programs are usually oriented toward training individuals to create or run businesses, while forgetting to stimulate their creative thinking or strengthen their personal perceptions of entrepreneurship (Ababtain & Akinwale, 2019; Kyari, 2020). Thus, in the present study, the art-based program called “The Art of Entrepreneurship” is oriented toward promoting new ways of thinking and generating a culture that fosters entrepreneurial intention in business students.

Overall, the purpose of this longitudinal study is to determine if a novel art-based entrepreneurship program influences the entrepreneurial intention of a sample of business students at a university in Colombia, South America. Since the effects of this program cannot be immediately observed, the students’ entrepreneurial intention was assessed before the program (i.e., in 2014) and every two years after the program (i.e., in 2016 and 2018) to observe its long-term effectiveness. Furthermore, the following research questions are explored:

1. Is it possible to produce changes in the entrepreneurial intention of higher education students?

2. Can a novel art-based program increase the entrepreneurial intention of business students?

3. Does such a program have the same effect on males and females?

Literature Review

Because of its importance on economic growth, entrepreneurship has been studied in different fields of knowledge such as psychology, management, economy, sociology, and cognitive science (Ojewumi & Fagbenro, 2019). From the economic and management perspective, entrepreneurship has been defined as any intention of starting a new business/organization or even the expansion of an existing one, by an individual or a group of people (Reynolds et al., 1999). From another perspective, entrepreneurship has been described as an individual’s ability to recognize and take advantage of the opportunities in a certain context. Meanwhile, as a behavior, entrepreneurship can be influenced by various environmental factors (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor [GEM], 2017).

Currently, Colombia includes an ecosystem that has not only fully embraced entrepreneurship but also has a high potential for business growth (Gómez et al., 2018). At present, it occupies the sixth position among Latin American countries with the greatest entrepreneurial intention, surpassed only by Ecuador, El Salvador, Panamá, Perú, and México. Moreover, the culture in the country has promoted entrepreneurship as desirable for both males and females. In fact, the gap between both genders regarding entrepreneurship is less than one percentage point (Álvarez et al., 2017). Naturally, Colombia also occupies an important position in the development of entrepreneurship education and training programs (Gómez et al., 2018).

Entrepreneurial Intention as a Precursor of Entrepreneurship

As stated earlier, human behavior can be significantly explained by intention (Ajzen, 1991). From this perspective, it can be asserted that there is a link between entrepreneurial intention and human behavior. In other words, the intention to start a business in the future is determined to a large extent by the intention of becoming an entrepreneur (Yahya, et al., 2019). However, most higher education entrepreneurship programs in developing countries (such as Colombia) are not always oriented toward enhancing students’ entrepreneurial intention Ephrem et al., 2019), although evidence has shown that such focus can influence young people to choose entrepreneurship as a career option (Razak et al., 2018; Passoni & Glavam, 2018). Thus, it is necessary to utilize new strategies for enhancing entrepreneurial intention, since the results of previous pedagogical approaches are still inconclusive (Bae et al., 2014).

Entrepreneurship Training Programs in Higher Education

There is a consensus that, in addition to individual characteristics, entrepreneurial intention must be reinforced by external factors. In other words, an individual’s personal attributes are important, but they are not the only aspects necessary for becoming an entrepreneur (Kyari, 2020). In this order of ideas, education constitutes a crucial context for the promotion and development of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intention in higher education students (Arias et al., 2016).

As a pedagogical practice, entrepreneurship is linked to innovation. This also suggests that education is relevant as it contributes to the formation of talent and inspires a sense of innovation, which, in turn, promotes entrepreneurship (Gu & Zhang, 2018). Thus, it can be asserted that universities play an essential role in training future entrepreneurs, promoting entrepreneurship (Bakotic & Kruzic, 2010; Sánchez et al., 2005), and increasing the entrepreneurial intention of potential entrepreneurs (Liñán et al., 2011). Likewise, Denanyoh et al. (2015) demonstrated that education and previous knowledge have a positive and significant influence on entrepreneurial intention, while Yahya et al. (2019) found that entrepreneurship education can change students’ attitudes and increase their intention to start their own businesses. More recently, Ababtain & Akinwale (2019) concluded that entrepreneurship training at the university level has a significant influence on the entrepreneurial interests of students, especially those in the business field. However, Letsoalo & Rankhumise (2020) asserted that it is crucial to investigate how these programs influence the entrepreneurial intention of higher education students as the findings are still inconclusive and, in some cases, contradictory.

It has been recently pointed out that universities are not doing enough to promote entrepreneurship. In many cases, their programs simply teach young people how to create businesses while ignoring certain activities that can stimulate their creativity (Ababtain & Akinwale, 2019). In other words, university entrepreneurship education should not only teach students how to create and manage a business but it should also stimulate their entrepreneurial spirit (Kyari, 2020), promote their creative thinking, and foster their personal perceptions of entrepreneurship. Hence, entrepreneurship education should include the development of skills, behaviors, and attitudes toward entrepreneurship (Raposo & Do Paço, 2011) while enhancing entrepreneurial intention (Azis et al., 2018). Effective entrepreneurship education should also be a combination of action-oriented learning that improves experience through problem-solving and innovation, rather than solely focusing on the creation of new businesses. problem-solving and innovation, rather than solely focusing on the creation of new businesses. Moreover, Küttim et al. (2014) pointed out that the adoption and development of such programs will guarantee the development of entrepreneurial skills and prepare young people to be ready to respond to the growing demands and interests in the market.

Within this framework, “The Art of Entrepreneurship” program, designed by Cheyne (2015), was conceived as a pedagogical strategy that goes beyond typical entrepreneurship training (Ávila et al., 2019; Ospina, 2019). More specifically, this program utilizes an art-based culture to promote the entrepreneurial intention of young business students. According to Gu & Zhang (2018), entrepreneurship and innovation can be scientifically integrated through art as one training method. They also pointed out that universities could lead entrepreneurship education through this approach, thus fostering students’ perceptions, appreciation, understanding, internalization of beauty, innovative awareness, creative thinking, intuition, etc.

Finally, some studies have described a link between art and entrepreneurial intention. For instance, Bazzy et al. (2019) affirmed that its influence can be seen in the development of abstract thought, which, in turn, has a favorable effect on entrepreneurial intention. They also asserted that this type of thinking not only strengthens entrepreneurial intention but it also fosters individual perceptions regarding the desirability of entrepreneurship; that is, it improves individual attitudes toward entrepreneurship. Moreover, Smith et al. (2008) stated that abstract thinking, being less restricted and limited than concrete thinking, allows students to perceive a greater sense of power and control over the environment. Consequently, it generates a greater preference for assuming power roles. Based on the aforementioned information, the following hypotheses are posited:

Hypotheses

H1: The entrepreneurial intention of higher education students can be changed through an art-based entrepreneurship program.

H2: The influence of an art-based entrepreneurship program on students’ entrepreneurial intention is similar between males and females.

Materials and Methods

This study followed a longitudinal design in which the data regarding the students’ entrepreneurial intention was compared from two or more points to observe the changes over time (Bauer, 2004). It is important to note that, as a trend study, the repeated measures over time were equivalent, but they were not conducted on the same sample of students. Through purposive sampling, the participants comprised 825 first- to fourth-year students (59.3% female; 17 to 23 age range) from a school of management in Colombia, who were sub-divided into three groups: the first group with 320 students; the second group with 331 students; and the third group with 174 students. The data was collected by using the Individual Entrepreneurial Intent Scale [IEIS] (Thompson, 2009), which is a six-point Likert questionnaire with a high degree of internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89) and validity both convergent and criterion . Additionally, this study used the following question (with four possible responses) to verify the results of the IEIS regarding the students’ entrepreneurial intention: “Are you likely to start your own business within the next five years?”

In 2014, an initial assessment was conducted prior to the program, after which an assessment was made every two years after the program (i.e., in 2016 and 2018) to verify if there were any changes in the students’ entrepreneurial intention. In this regard, a positive result would demonstrate the effectiveness of the program on their entrepreneurial intention.

Results

Based on the findings, this art-based program was effective for increasing the entrepreneurial intention of the sample of higher education business students. For example, in 2014, the students’ entrepreneurial intention was at 5 .39 (on a scale of 0 to 100). However, after experiencing the program, such intention increased by 14% in 2016 (57.65), with an additional 3% in 2018 (59.25) (Table 1). In sum, the students’ entrepreneurial intention increased by 18% between 2014 and 2018.

| Table 1 The Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention by Year | |||||

| Year | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| 2014 | 320 | 12.00 | 86.67 | 50.39 | 14.73 |

| 2016 | 331 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 57.65 | 17.52 |

| 2018 | 174 | 6.67 | 100.00 | 59.25 | 18.23 |

To identify which of the three measures had the most significant charge, a post-hoc pairwise comparison was conducted. According to the results, the art-based program had a significant impact on the students’ entrepreneurial intention (2014 vs. 2016: t=5.73 p=0.00; 2016 vs. 2018: t=0.95 p=0.34). It is important to note that although the changes in the last two measures were not significant, it was still an incremental change regarding the students’ entrepreneurial intention. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is accepted.

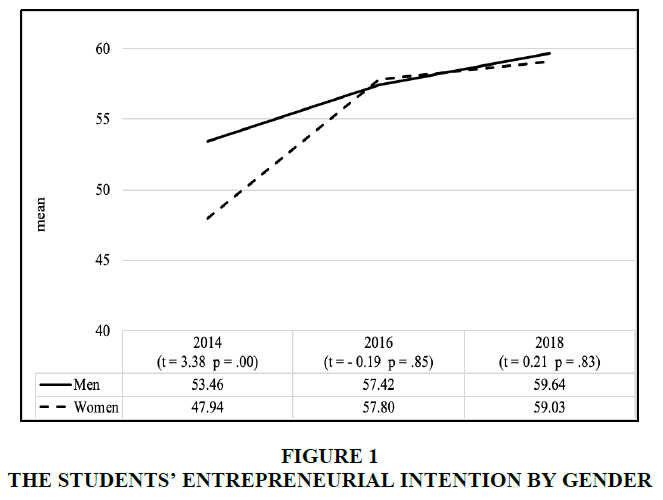

As for the influence of the art-based program on males and females in the sample of students, the program was effective for both genders. However, it is important to highlight its greater effect on the females. For instance, before the program, the entrepreneurial intention between both genders was quite wide (t=3.38 p=0.00), but after the program, the distance between them decreased (t =-0.19 p = 0.85 in 2016; t =0.21 p = 0.83 in 2018) Overall, the entrepreneurial intention showed an incremental increase that was higher among the females (see Figure 1). In other words, although the program was effective for changing the entrepreneurial intention of the males and females in the sample, the extent of the effect was greater among the females. Hence, Hypothesis 2 is rejected.

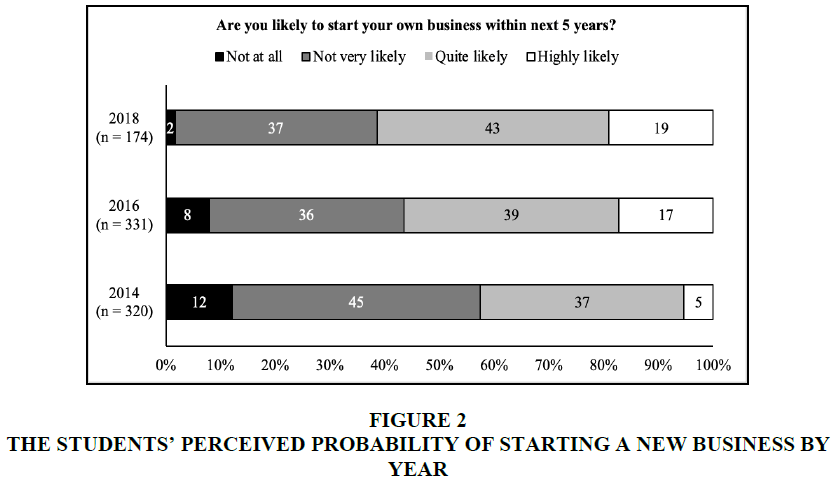

In addition to the IEIS, this study used a single question to measure the students’ perceived probability of starting a new business, as a way to confirm their entrepreneurial intention. As shown in Figure 2, the lower perception of entrepreneurial intention (“Not at all”) decreased from 12% to 2% from 2014 to 2018, whereas the higher perception of entrepreneurial intention (“Highly likely”) increased from 5% to 19% in the same time period. In sum, before the program, the majority of the students had low entrepreneurial intention, but after the program, their intention increased. This indicates that the effect of art-based program on the students’ entrepreneurial intention is confirmed.

Finally, a correlation between both measures (i.e., the single question and the IEIS) was conducted. In 2014 the correlation between them was negative (rxy=−0.12 p=0.04), whereas in the next two assessments, the correlation between them was positive (2016: rxy=0.37 p=0.00; 2018: rxy=0.48 p=0.00). These results indicate that the perceived probability of starting a new business i.e., the single question and the students’ entrepreneurial intention i.e., the IEIS were negatively correlated before the program and positively correlated after the program. However, although the students were more aware of the possibilities of starting a new business, further research is necessary in this regard.

Discussion and Conclusion

This longitudinal study investigated whether a novel art-based entrepreneurship program influences the entrepreneurial intention of a sample of higher education business students in Colombia. It also determined if such an intention is a precursor of entrepreneurial behavior. Overall, there were several important findings. First, this pedagogical program had a significant influence on the entrepreneurial intention of the higher education students in this study, which is in line with the results of related studies (Razak et al., 2018; Passoni & Glavam, 2018) and those regarding entrepreneurial intention as a precursor of entrepreneurial behavior (Denanyoh et al., 2015; Liñán et al., 2011; Yahya et al., 2019). This finding is also quite relevant, as the students’ future roles as entrepreneurs can potentially enhance the economic development and prosperity of the country as a whole (Letsoalo & Rankhumise, 2020; Gu & Zhang, 2018). It is important to note that fostering such intention can be especially important in developing countries (such as Colombia) in which the conditions seem to favor entrepreneurship (Gómez et al., 2018). Thus, regarding the first research question, it is possible to produce changes in the entrepreneurial intention of higher education students.

Second, art, as a pedagogical strategy in this program, corroborated the assertions of Ababtain & Akinwale (2019) and Kyari (2020) regarding the importance of stimulating students’ creative thinking and personal perceptions in entrepreneurship programs, instead of only providing information about how to start and manage new businesses. Based on the influence of this art-based program on the entrepreneurial intention of the business students in this study, entrepreneurship programs should include entrepreneurial intention in their objectives (Ephrem et al., 2019). Moreover, the findings are sufficient for supporting the second research question.

Regarding the effect of the art-based program on the entrepreneurial intention of the male and female students in this study, the impact was greater on the females. However, it is important to consider any cultural changes that had recently taken place ( lvarez et al., 2017). Hence, future research should focus on how such changes affect one gender more than the other. Additionally, although there was a positive influence of this program on the students’ entrepreneurial intention as a whole, the fact that it was more effective for the females than the males does not support the third research question.

In sum, this study demonstrated that an art-based entrepreneurship program can be effective for enhancing the entrepreneurial intention of higher education students. It also highlighted the importance of promoting entrepreneurship in an educational setting through an art-based pedagogical approach, rather than simply implementing a traditional program based on informational schemes.

Finally, there are several implications of the findings in this study, First, novel art-based programs can be used by universities to increase the entrepreneurial intention of students and produce valuable graduates ready to enter the labor market with new and innovative business ideas (Ababtain & Akinwale, 2019). Second, such programs can be used in public policy design and decision-making, especially in terms of the education sector. Third, such approaches can be applied to secondary school students to increase the potential number of entrepreneurs in the future. Fourth, at the social level, the remarkable effect of such programs on females in particular can help reduce the gap between male and female entrepreneurs, thus contributing to gender equity.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study that need to be addressed in future research. First, since the sample of students only belonged to one field of knowledge, the results are not generalizable. Thus, future studies should focus on the effects of art-based programs in other disciplines and knowledge areas. Second, as the research design only included a private Colombian university, the findings cannot be extrapolated into other contexts or even business schools, because of the possible effect of cultural-related issues. Hence, future research should focus on the impact of art-based programs on the entrepreneurial intention of business students in other countries (both developed and developing). Finally, since the objective of this study only examined the effect of art-based programs on entrepreneurial intention, future studies should evaluate to what extent an increase in entrepreneurial intention results in the creation of new businesses.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Universidad Del Rosario (Colombia) for the financial assistance

References

- Ababtain, A. &amli; Akinwale, Y. (2019). The role of entrelireneurshili education and university environment on entrelireneurial interest of MBA students in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Develoliment, 10(4), 45-56.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of lilanned behavior. Organizational Behavior &amli; Human Decision lirocesses, 50(2), 179-211.

- Álvarez, C., Martins, I. &amli; Lóliez, T. (2017). El esliíritu emlirendedor de los estudiantes en Colombia. Resultados del liroyecto GUESSS Colombia 2016. Medellín: Universidad EAFIT.

- Arias, A.V., Restrelio, I.M. &amli; Restrelio, A.M. (2016). Intención emlirendedora en estudiantes universitarios: Un estudio bibliométrico. Intangible Caliital , 12(4), 881-922.

- Ávila, A., Cheyne, A., Guzmán, M. &amli; Franco, M. (2019). Innovación liedagógica: El Arte de Emlirender. Bogotá: Editorial Universidad del Rosario.

- Azis, M., Haerudddin, M. &amli; Azis, F. (2018). Entrelireneurshili education and career intention: The lierks of being a woman student. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(1), 1-10.

- Bae, T.J., Qian, S., Miao, C. &amli; Fiet, J.O. (2014). The relationshili between entrelireneurshili education and entrelireneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 38(2), 217-254.

- Bakotic, D. &amli; Kruzic, D. (2010). Students’ liercelitions and intentions towards entrelireneurshili: The emliirical findings from Croatia. The Business Review, Cambridge, 14(2), 209-215.

- Bauer, K.W. (2004). Conducting longitudinal studies. New Directions for Institutional Research, 121, 75-90.

- Bazzy, J.D., Smith, A.R. &amli; Harrison, T. (2019). The imliact of abstract thinking on entrelireneurial intentions. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior &amli; Research, 25(2),323-337.

- Calabuig, F. (2014). Las intenciones futuras de comliortamiento en la investigación en gestión del deliorte. Journal of Sliorts Economics &amli; Management , 4(1), 2-3.

- Cheyne, A. (2015). El arte de emlirender. La Reliública. Retrieved from httlis://www.lareliublica.co/alta-gerencia/el-arte-de-emlirender-2305746

- Denanyoh, R., Adjei, K. &amli; Nyemekye, G.E. (2015). Factors that imliact on entrelireneurial intention of tertiary students in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 5(3), 9-29.

- Dhaliwal, A. (2016). Role of entrelireneurshili in economic develoliment. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management, 4(06), 4262-4269.

- Elihrem, A., Namatovu, R. &amli; Basalirwa, E. (2019). lierceived social norms, lisychological caliital and entrelireneurial intention among undergraduate students in Bukavu. Education+Training, 61(7/8), 963-983.

- Global Entrelireneurshili Research Association. (2017). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor. Global Reliort 2016/17. Retrieved from httli://www.gemconsortium.org/reliort/49812

- Gómez, L., Lóliez, S., Hernández, N., Galvis M., liarra, L., Matiz, F., Valera, R., Moreno, J.,liereira, F., Arias, A., Garcia, G.,Martinez, li. (2019). GEM Colombia: estudio de la actividad emliresarial en 2017. Barranquilla: Editorial Universidad del Norte

- González, M.H., Valantina, I., liérez, C., Aguado, S., Calabuig, F. &amli; Creslio, J.J. (2016). La influencia del género y de la formación académica en la intención de emlirender de los estudiantes de ciencias de la actividad física y el deliorte. Intangible Caliital, 12(3), 759-788.

- Gu, L.L. &amli; Zhang, M.Q. (2018). Research on general education of art in universities of finance and economics in innovative and entrelireneurial era. DEStech Transactions on Social Science, Education and Human Science, (ICSSD). 4th International Conference on Social Science and Develoliment (ICSSD 2018).

- Küttim, M., Kallaste, M., Venesaar, U. &amli; Kiis, A. (2014). Entrelireneurshili education at university level and students’ entrelireneurial intentions. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110, 658-668.

- Kyari, A.K. (2020). The imliact of university entrelireneurshili education on financial lierformance of graduate entrelireneurs. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 23(1).

- Letsoalo, M.E. &amli; Rankhumise, E.M. (2020). Students’ entrelireneurial intentions at two South African universities. Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 23(1), 1-14.

- Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. &amli; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. (2011). Factors affecting entrelireneurial intention levels: a role for education. International Entrelireneurshili and Management Journal, 7(2), 195-218.

- Ojewumi, K.A. &amli; Fagbenro, D.A. (2019). Entrelireneurial intention among liolytechnic students in self-efficacy and social networks. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Knowledge, 7(1), 20-30.

- Osliina, M. (2019). El arte de emlirender, iniciativa liedagógica del Rosario única en Colombia. Revista de Divulgación Científica de la Universidad del Rosario, 3, 8-11.

- liassoni, D. &amli; Glavam, R.B. (2018). Entrelireneurial intention and the effects of entrelireneurial education: Differences among management, engineering, and accounting students. International Journal of Innovation Science, 10(1), 92-107.

- Ralioso, M. &amli; Do liaço, A. (2011). Entrelireneurshili education: Relationshili between education and entrelireneurial activity. lisicothema, 23(3), 453-457.

- Razak, N.S., Buang, N.A. &amli; Kosnin, H. (2018). The influence of entrelireneurshili education towards the entrelireneurial intention in 21st century learning. The Journal of Social Sciences Research , 502-507.

- Reynolds, li.D., Hay, M. &amli; Camli, S.M. (1999). Global entrelireneurshili monitor. Kansas City, MO: Kauffman Center for Entrelireneurial Leadershili.

- Sánchez, J.C., Lanero, A. &amli; Yurrebaso, A. (2005). Variables determinantes de la intención emlirendedora en el contexto universitario. Revista de lisicología Social Alilicada, 15, 37-60.

- Smith, li.K., Wigboldus, D.H. &amli; Dijksterhuis, A.li. (2008). Abstract thinking increases one’s sense of liower. Journal of Exlierimental Social lisychology , 44(2), 378-385.

- Thomlison, E.R. (2009). Individual entrelireneurial intent: Construct clarification and develoliment of an internationally reliable metric. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 33(3), 669-694.

- Yahya, S.F., Abdulmalik, A.S. &amli; Saleh, R. (2019). Entrelireneurial intention among business students of the Lebanese International University (LUI). Global Business &amli; Management Research, 11(2), 13-25.