Research Article: 2022 Vol: 28 Issue: 1

Entrepreneurial Marketing and A New Integrative Model: An Evaluation of the Survival of Manufacturing Small and Medium Enterprises

Cosmas Anayochukwu Nwankwo, University of Kwazulu-Natal

Macdonald Isaac Kanyangale, University of Kwazulu-Natal

Citation Information: Nwankwo, C.A., & Kanyangale, M.I. (2022). Entrepreneurial marketing and a new integrative model: An evaluation of the survival of manufacturing small and medium enterprises. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 28(1), 1-13.

Abstract

Many manufacturing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Nigeria cease to exist before their fifth birthday. The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of entrepreneurial marketing on the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria using a new integrative entrepreneurial marketing model that would help ensure the survival of SMEs in Nigeria. The quantitative study used positivism as research paradigm while stratified random sampling was employed to select owner-managers of manufacturing SMEs in the South-East geo-political zone of Nigeria. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire administered to 364 owner-managers. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were used to test the reliability after a pilot study had been conducted. Exploratory fact analysis and inferential statistics, such as Pearson’s correlation coefficient and multiple regressions analysis, were applied to test the hypothesis via IBM SPSS statistics version 25. The results indicated that entrepreneurial marketing has a direct and significantly positive effect on the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria. The tested integrative EM model showed that proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, customer intensity, value creation, market sensing and teamwork have a direct and significant positive effect on SMEs' survival. However, innovativeness, considered one of the key dimensions of entrepreneurial marketing, shows a significant but negative effect on SME survival. Alliance formation showed no significant effects. In the light of these results, the study developed a new model of entrepreneurial marketing for manufacturing SMEs by incorporating teamwork and market sensing in the existing model. The new integrative entrepreneurial marketing model is valuable to owner-managers to enhance the survival of their businesses and reduce failures and to academics as a basis for robust future research. The study recommended the adoption of the new integrative entrepreneurial marketing model in the management of manufacturing SMEs to aid survival.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Marketing, Integrative Entrepreneurial Marketing, Entrepreneurial marketing dimensions, SME survival.

Introduction

Adopting an entrepreneurial mind-set by small and medium enterprises (SMEs) is pivotal in pursuing marketing activities. This mindset is particularly proper in the manufacturing sector in Nigeria, where SMEs strive to survive and contribute to the economy. Marketing, a vital business activity for survival and growth, is one of the most significant problems SMEs face, especially in Nigeria's manufacturing sector. SMEs are regarded as the pivotal backbone of the Nigerian economy, not only because they constitute about 87% of all enterprises. Notably, SMEs also contribute about 61% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Effiom & Edet, 2018).

The basic principles and traditional marketing models which govern large businesses are not always applicable to the SME context. It is thus not surprising that many SME owner-managers have an unenthusiastic attitude towards traditional marketing ideas and consequently afford marketing activities a low priority compared to other business activities (Resnick et al., 2016). Despite this apparent low-key approach, studies reveal that marketing and entrepreneurial competency are crucial to the survival and development of SMEs (Kasouf et al., 2008; Lusch & Vargo, 2014). Marketing and entrepreneurship scholars are increasingly interested in delving into marketing for entrepreneurs (such as new ventures marketing), marketing for entrepreneurial ventures (such as those aimed at stimulating growth and innovation) or entrepreneurship for marketing (such as innovative marketing). The question of marketing in the context of SMEs has highlighted two cardinal issues for scholars of entrepreneurship and marketing. The first issue is the notion of marketing carried out by entrepreneurs who are decision-makers in a context typified by simple systems and procedures that permit flexibility, immediate feedback, a short-decision chain, better understanding and response to customer needs. There is a lack of marketing specialists in SMEs in Nigeria. If SMEs are to survive in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous context (VUCA) in Nigeria, they need entrepreneurial action and marketing characterised by innovation, risk-taking, and proactiveness performed without resources currently controlled. There is a growing acknowledgement that entrepreneurial marketing (EM) is a unique concept characterised by a variety of factors which include: being inherently informal, restricted to the sphere of activity, opportunistic in nature, founder-entrepreneur involvement and highly dependent on networking. Entrepreneurs who are innovative, calculative risk-takers, proactive and opportunity-oriented manifest EM behaviours derived from entrepreneurial thinking. Chell et al. (1991) observed that EM represents a more unconventional and unorganised practice that relies on people's intuition and energy to make things happen. Intuitive learning involves acknowledging the relationships amongst facts by discovering possibilities (Chell et al., 1991). Based on this, intuitive entrepreneurs are often considered abstract thinkers who are more likely to create new opportunities based on a high level of conceptual thinking and discovering possibilities.

As practised by entrepreneurs, marketing is somehow different from the conventional concept of marketing often discussed within scholarly literature. Conventional marketing relates to an organised marketing structure that requires a careful planning process guided by research to ensure correct target market selection and marketing mix. Traditional marketing is done in an effort to competitively position products within the marketplace (Nwaizugbo & Anukam, 2014).

The second issue relates to scholars having deciphered the qualitative and quantitative aspects of EM fundamental to exploring the nature of SME marketing (Effiom & Edet, 2018; Gamage, 2014). When considered from the qualitative viewpoint, EM emphasises marketing with an entrepreneurial mindset which is pivotal to the success of any enterprise, irrespective of size, age or resources. Within the qualitative domain, EM is about marketing that diverges from mainstream marketing to focus on marketing activities adopted in highly successful firms to grow and market entrepreneurial firms. Alternatively, the quantitative aspect of EM underscores that this type of marketing is aimed at a small and/or new venture. The quantitative dimension of EM highlights the danger of newness (e.g. lack of established market partner relationships and procedures within the firm) and smallness (e.g. limited financial and human resources as well as limited market power and a small customer base) to marketing activities characterised by innovation, risk-management and proactiveness. Ultimately EM, as an enterprise-size related phenomenon, is cardinal in economies where SMEs comprise a significant part of the economy (Carter & Tamayo, 2017). For instance, it is estimated that about 70% of the businesses in Ghana can be classified as SMEs, and, as such, they contribute 40% of the GDP. There are approximately 1.3 million micro and small businesses in Kenya, employing over 2.3 million people and thus creating wealth and export opportunities. Similarly, 91% of all the registered businesses in South Africa resort under SMEs, comprising about 52 to 57% of the country’s GDP (Dimoji & Onwumere, 2016; Ganyaupfu, 2013). To survive in this competitive arena, SMEs need to proactively identify and seize opportunities towards acquiring and retaining profitable customers and engage in entrepreneurial marketing (Dimoji & Onwuneme, 2016; Etuk et al., 2014).

The SME sub-sector of the Nigerian manufacturing sector has remained a key and essential component for socio-economic development and growth in Nigeria (Eniola, 2014). In terms of GDP growth and contribution to the distribution of wealth across all sectors of the economy, manufacturing SMEs are considered driving forces in the Nigerian economy’s manufacturing sector (Aremu & Adeyemi, 2011). Several factors suppress the business environment and contribute to the high rate of SME failure, especially in the manufacturing sector (Ene & Ene, 2014). Studies have observed that 85% of businesses in Nigeria do not live beyond their fifth year, despite efforts made by the Nigerian government and other supportive agents (Effiom & Edet, 2018; Gwadabe & Amirah, 2017). The small percentage which survives beyond their fifth-year collapse between their sixth and tenth year of existence. Therefore, Onugu states that only about 5 to 10% of SMEs remain in existence (Gwadabe & Amirah, 2017). Despite these poor survival rates, manufacturing SMEs are generally uninterested in marketing as a vital business activity. They consider it something done by large organisations and thus ambiguous to the smaller concern (Resnick et al., 2016; Uchegbulam et al., 2015). Existing literature reveals that marketing practised by small enterprises differs from marketing practices adopted by larger firms. This distinction is particularly true in the case of manufacturing SMEs where changing business environments, the adoption of good management cultures and, above all, owner-managers' philosophies in terms of skills, abilities and resources come into play (Olaniyan et al., 2017). Some scholars argue that manufacturing SMEs’ marketing practices and decision-making activities, when compared to their counterparts in large enterprises, tend to be prolific, different, intuitive unorganised and unconventional (Gilmore, 2010) as well as chaotic and unplanned.

In manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria, there are poor survival rates and negative attitudes toward marketing. Research in Nigeria and beyond has started to consider how manufacturing SMEs could sustain themselves using entrepreneurial marketing (EM) models. The majority of previous studies which have delved into the issue of EM adopted the model by Morris, Schendehutte and Laforge’s (2002) which comprise seven-dimensions because of the elaborate way in which it operationalises key constructs (Mehran & Morteza, 2013; Mugambi & Karugu, 2017; Nwaizugbo & Anukam, 2014; O'Cass & Morrish, 2016; Olaniyan et al., 2017; Taghipourian & Gharib, 2015). However, studies that adopted (Morris et al., 2002) model exhibited two critical shortfalls. Firstly, they failed to prioritise customers and therefore, the customer was not considered as the king in all business transactions. This failure invokes the serious question of how can an EM model be expected to wield explanatory power if customers are considered peripheral in the construct? Secondly, the model fails to acknowledge the need and value of cooperation (teamwork), which should exist between entrepreneurs and their subordinates and customers. These observations raise serious questions regarding the construct validity of EM in previous studies.

In addition, a review of extant literature reveals that studies carried out in the EM domain have investigated this concept in relation to a variety of other issues, including performance, innovation and development, but not in relation to the survival of SMEs (Nwankwo & Kanyangale, 2020). Previous studies in Nigeria have focused on the service sector (Nwaizugbo & Anukam, 2014). Therefore, no studies have investigated the role of EM in the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria and/or subsequently provided an empirically tested model. A need thus exists to address this research gap with empirical studies investigating the effects of EM on the survival of manufacturing SMEs. Mindful of the critical shortfalls in models used to study EM in previous studies, this study seeks to address this gap by drawing on the works of various scholars, including (Morris et al., 2002); (Neneh, 2011); (Wörgötter (2011) as well as (Van Vuuren & Wörgötter 2013), to conceptualise and subsequently develop a robust model to show how EM affects the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria.

Unlike previous studies, this research holds that the customer should be placed centrally in EM if manufacturing SMEs are to survive in Nigeria. Although Morris Schindehutte & LaForge.’s (2002) model is a popular choice with researchers, it has not been adopted in its entirety in this study because of its shortfalls. As such, modifications were made in this study to highlight the essential role of teamwork and customer relationship management to any model which might attempt to meaningfully reflect the role of EM in the context of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria. Given the previous models of EM and modifications made for the purpose of this research, the aim is to investigate the effects of EM on the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria. This aim of the study is hypothesised as:

Ho: Entrepreneurial marketing (EM) dimensions do not influence the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria.

Conceptualising A New Integrative Model Of Em For Smes

As reflected by Morris, Schindehutte & LaForge (2002) framework, the dimensions of EM are significant and relevant but need to be modified and integrated to address the identified shortfalls. For example the solid foundation of EM, as described by Morris, Schindehutte & LaForge (2002) needs to be modified in the following ways: incorporation of an opportunity as key in the market-driving orientation (Wörgötter, 2011) and the introduction of a teamwork dimension (Neneh, 2011). Firstly, it is critical to underscore that the dimension of opportunity focus is important but too restricted as it emphasises known, but unsatisfied customer needs. This dimension of opportunity focus does not consider latent customer needs. Simply put, a latent need refers to a problem that a customer does not even realise he/she had. Latent needs refer to preferences or desires, which cannot be satisfied due to a lack of information or the unavailability of a product or service. In the light of this, there is a need for EM to incorporate an opportunity focus dimension into a market-driving orientation that is relatively broad. Market driving is defined as changing the composition of roles, or behaviours, of market players (Ghauri et al., 2016). In this regard, market-driving is the owner-manager’s ability which includes market sensing (e.g. environmental scanning or opportunity scanning) and alliance formation (e.g. creating a solid relationship with partners/suppliers). The market-driving ability is influenced by the entrepreneurial and market approach as well as cultural orientation (Agarwala et al., 2017). Clearly, market-driving orientations (such as opportunity scanning, business alliance and other market indicators) are pivotal as they supply a manager with a strategic entrepreneurial sense of opportunity and competitive advantage (Ghauri et al., 2016).

Secondly, teamwork is another dimension likely to add value to the already existing EM model by Morris ; Schindehutte & LaForge (2002). Combined team effort is key to attaining a common objective or completing a task most efficiently and effectively (Ooko, 2013). Notably, a firm with a controllable force over other dimensions, as presented by Morris; Schindehutte & LaForge (2002), which fails to engage in the cooperative activity (teamwork), would eventually face challenges. Neneh (2011) concurs that the advantages of teamwork include: enhancing a firm's performance, strengthening employees' well-being, reducing fluctuations in performance, improving work morale, creating an environment that facilitates knowledge and information exchange and knowledge sharing. These would all aid in SMEs' survival.

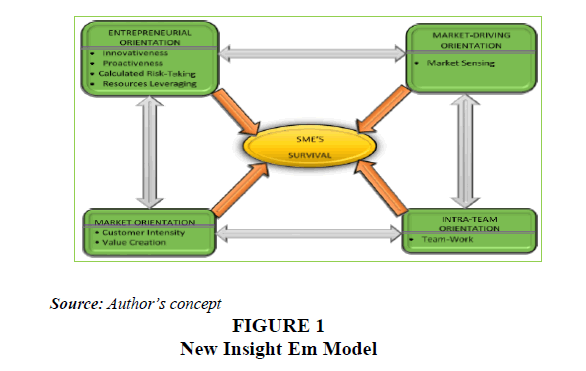

In this study, an integrative EM model is designed based on the works of three different scholars, namely Morris Schindehutte & LaForge, (2002); Wörgötter (2011); Neneh (2011) to ultimately suggest nine EM dimensions that would influence the survival of an SME from the owner-manager’s point of view. In the conceptualised integrated model, there are nine dimensions that can be categorised into four variables of entrepreneurial orientation (EO), market orientation (MO), market-driving orientation (MDO) and intra-team orientation (IO). These nine dimensions, and their interrelationships, form part of EM and are depicted in the integrated EM model.

The Manufacturing Smes in Nigeria

In Nigeria and beyond, SMEs are active in all sectors of the economy, including manufacturing, agriculture, mining, construction, service and transportation, to name but a few. In Nigeria, these sectors contribute to economic growth - both in the past and presently. However, this study will focus on the manufacturing sector, as SMEs in Nigeria represent about 90% of the manufacturing/industrial sector in terms of the number of enterprises (CBN, 2018).

The manufacturing sector plays an essential and vital role in the domestic and global economy Eziashi (2017); UNIDO (2013). The demand for manufactured goods is maintaining steady growth as people worldwide continue to enter the global consumer class (NIRP, 2014). The manufacturing sector has, in recent times, contributed about 17% of the global US$ 70 trillion economies and accounts for over 70% of world trade (McKinsey Global Institute, 2013). As economies continue to grow, the role of manufacturing becomes increasingly important, and its impact on the economy expands (KPMG, 2016; McKinsey Global Institute, 2013). In the recent past, the manufacturing sector of the Nigerian economy has continued to show little or no growth and has failed to undergo fundamental structural changes essential to adopting a leading role in economic growth and development (Eziashi, 2017; Malik et al., 2002). The sector is structurally weak and ineffective. Basic industries, such as iron, steel, cement and the automobile industry, which should be driving growth, are functioning to capacity and have, in some instances, become moribund (NIRP, 2014). In many sectors, a technological base for manufacturing in Nigeria is absent. Experienced manpower, which is necessary to foster competitiveness in today’s volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) business environments, is thus inadequate or totally lacking (McKinsey Global Institute, 2013). Generally, the systemic problem regarding infrastructure, non-compliance with modern technological trends, a lack of marketing ideas, power failures and a poor transport network have resulted in rising costs and non-competitive operations of Nigerian manufacturing SMEs (NIRP, 2014).

Consequently, the Nigerian manufacturing SME sector has not been able to make the required investment necessary to stimulate economic growth. This has caused Nigerian manufacturing SMEs to remain small players in the Nigerian economy. Additionally, the Nigerian manufacturing SME sector’s share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the economy has not exceeded a 4% contribution to foreign exchange earnings. This has resulted in a loss of jobs and low revenue generation for the government.

However, Nigeria’s readiness to join the global consortium of developed countries has been highlighted by its government’s pro-active measures to develop the manufacturing SME sector of the economy (NIRP, 2014). Manufacturing is pivotal to driving development and social change, and it plays a unique role due to its connection with other areas of the economy. Manufacturing thus forms a principal base for the economic health and security of the country. The “Nigerian economy has grown at an average rate of 6.5% annually between the years 2005 and 2015 and in 2016, the economy entered into a recession with GDP contracting by 0.36% in the first quarter, 2.1% in the second quarter and 2.2% in the third quarter” (ERGP, 2017). It is important to note that the SMEs that participated in this study manufacture various products, including kitchenware, beverages, bottled and sachet water, clothing and footwear, cables, ceramics, and confectionaries. Given this clarification, the label of manufacturing SMEs, as employed in this study, refers to SMEs that have existed for five years and longer, are independent and not externally controlled, and employ fewer than 200 individuals. It is relevant to clarify this conception as many different definitions and criteria can be used to define SMEs.

Methodology

The paper is a quantitative study that adopted a positivistic ontology and descriptive survey design. In this study, the population sizes were obtained from the five-state ministry of commerce and industry. The study was limited to owner-managers of manufacturing SMEs in the five states in the south-eastern of Nigeria. The overall population size in the five states were 11, 573 owner-managers of manufacturing SMEs.

The study adopted the Yamani sample formula to determine the sample of 387 owner-managers in south-eastern geo-political zone of Nigeria. Afterwards, a stratified sampling technique (proportionate) was used to select participants from each state studied. As stated above, the study randomly selected 387 owner-managers of the registered SMEs in South-Eastern geo-political zone of Nigeria. These owner-managers of manufacturing SMEs were selected because of the following factors; (1) they had operated manufacturing SMEs which had survived for not less than five years, (2) located in an area with limited ethno-political and religious crises, and (3) proximity purpose.

Data were collected from manufacturing SMEs using a structured questionnaire. A total of 387 copies of the questionnaire were administered both electronically (email) and manually to the owner-managers of manufacturing SMEs. 369 copies were returned. Out of the number returned, 364 copies were discovered to be useful, representing a response rate of 94.05 per cent.

Content validity was used to adequately measure coverage of the research topic and a trial test to estimate the instrument's internal consistency. Cronbach alpha was used for internal consistency measured at 0.749. The hypothesis was tested using multiple regression analysis to measure the effect of EM dimensions (proactiveness, innovativeness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, customer intensity, value creation, market sensing, alliance formation, teamwork) on the survival of manufacturing SMEs.

Analysis of Results

The null hypothesis states that EM dimensions do not influence the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria. To test the relationship between EM dimensions and the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria, this study employed Pearson’s correlation coefficient and multiple regressions analysis. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to ascertain the relationship between the overall EM dimensions and SME survival, while multiple regressions analysis was utilised to ascertain the contribution of each EM dimension to manufacturing SMEs’ survival. Table 1 illustrates the correlation coefficient between these variables.

| Table 1 Pearson’s Correlation Between Em Dimensions And Sme Survival |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| EM Dimensions | SME Survival | ||

| EM Dimensions | Pearson’s Correlation | 1 | 580** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 364 | 364 | |

| SME Survival | Pearson’s Correlation | 580** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | ||

| N | 364 | 364 | |

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). | |||

Table 1 reveals the correlation coefficient between EM dimensions and the survival of SMEs (r=0.580, p<0.05). From the correlation coefficient table, it is evident that all EM dimensions are positively and significantly correlated with the dependent variable (SME survival). The value of p is lower than 0.05 and the correlation coefficient is 0.580 or 58.0%. With this level of significance, the null hypothesis was rejected, and this implies that there is a positive and significant relationship between EM dimensions (innovativeness, proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, customer intensity, value creation, market sensing, alliance formation and teamwork) and SME survival in Nigeria. However, the relationship between the two variables is not only significant but equally strong and positive. Having acknowledged the relationship between EM dimensions and SMEs’ survival, further tests were carried out using multiple regressions analysis to ascertain the individual contribution of each EM dimension on the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria. The EFA results are presented in Table 2 measure the factor loading of each of the entrepreneurial marketing dimensions as found in the integrative EM model.

| Table 2 Exploratory Factor Analysis Of The Measurement Of Entrepreneurial Marketing Dimensions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Mean | SD | Factor loading | Item total correlation |

| Entrepreneurial marketing dimensions Factor 1 |

||||

| Teamwork | 4.79 | 1.717 | 0.874 | 0.542 |

| Proactiveness | 4.52 | 0.452 | 0.799 | 0.426 |

| Calculated Risk-taking | 4.40 | 0.517 | 0.711 | 0.391 |

| Value creation | 4.05 | 1.249 | 0.692 | 0.394 |

| Market Sensing | 4.01 | 0.772 | 0.681 | 0.386 |

| Innovativeness | 4.14 | 0.491 | 0.621 | 0.461 |

| Customer Intensity | 3.92 | 1.831 | 0.601 | 0.411 |

| Resource Leveraging | 4.33 | 0.602 | 0.594 | 0.383 |

| Alliance Formation | 3.31 | 0.413 | 0.430 | 0.267 |

KMO=0.813; X2=725.528; DF=8; P˂.000; Cronbach’s α=0.749; Percentage of variance explained =59.92%.

In this study, reliability was used to examine the level of internal consistency of the several measurements used in the research construct. The internal consistency of components, or factors, and the respective items which emerged from the EFA measurement were analysed separately using Cronbach's alpha coefficient via IBM SPSS statistics version 25. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients are: innovativeness (0.691), proactiveness (0.723), calculated risk-taking (0.611), resource leveraging (0.686), value creation (0.722), customer intensity (0.683), market sensing (0.799), alliance formation (0.606) and teamwork (0.782). A factor consisting of a nine items measurement of SME survival produced an internal consistency of 0.782. No factor was excluded in the measurement model as the results of Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were above 0.600 or 0.700. Based on the results of the EFA, the entrepreneurial marketing dimensions of the integrative EM model in this study were examined via the multiple regression analysis/model measurement depicted in Table 3. The result also integrates model summary, ANOVA and coefficients in one broad table to provide a clear and holistic view.

The regression model, as per Table 3, shows an R square of 0.505 and an adjusted R square of 0.445. This means that the model (EM dimensions) predicts 44.5% of the variations in the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria. This is significant at p˂0.05, meaning that there is a significant relationship between the independent variables of different dimensions of EM and the dependent variable, namely SME survival. These results support the alternative hypothesis, which states that EM dimensions influence the survival of manufacturing SMEs. Notably, the standardised Beta and the corresponding P-values for innovativeness (β=-0.197, p˂0.010), proactiveness (β=0.178, p˂0.001), calculated risk-taking (β=0.167, p˂0.002), resource leveraging (β=0.161, p˂0.012), customer intensity (β=0.143, p˂0.011), value creation (β=0.140, p˂0.045), market sensing (β=0.109, p˂0.036) and teamwork (β=0.103, p˂0.039), show that teamwork made the largest contribution to the model, followed by proactiveness and then the other dimensions. With these results in mind, one can say that proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, customer intensity, value creation, market sensing and teamwork jointly serve as a predictor of SME survival in the manufacturing sector in Nigeria, while innovativeness also made a unique contribution with respect to SME survival in this study. In the light of this, one can state that there is a significant positive relationship between EM dimensions and SME survival in Nigeria.

| Table 3 Em Dimensions As Predictors Of Sme Survival |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | R square | Adjusted R square | F | Beta | t | Sig | ||

| 0.711a | 0.505 | 0.445 | 20.797 | ---- | ---- | 0.000b | ||

| Innovativeness | -0.197 | -2.590 | 0.010 | |||||

| Proactiveness | 0.178 | 3.320 | 0.001 | |||||

| Calculated Risk-taking | 0.167 | 3.147 | 0.002 | |||||

| Resource Leveraging | 0.161 | 2.531 | 0.012 | |||||

| Customer Intensity | 0.143 | 2.571 | 0.011 | |||||

| Value creation | 0.140 | 2.014 | 0.045 | |||||

| Market Sensing | 0.109 | 2.103 | 0.036 | |||||

| Alliance Formation | 0.058 | 1.025 | 0.306 | |||||

| Teamwork | 0.309 | 3.435 | 0.001 | |||||

| (Constant) | --- | 2.715 | 0.007 | |||||

| a. Dependent Variable: SME survival b. Predictors: (Constant) innovativeness, proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, customer intensity, value creation, market sensing, alliance formation, teamwork. |

||||||||

Discussion Of The Validated Integrative Em Model

As noted earlier, the impetus of this new integrative EM model arises from the constant failure of SMEs in Nigeria, as acknowledged by several past studies (e.g. Gwadabe & Amirah, 2017; Kesinro et al., 2016; Roldan, 2015). Several studies have been conducted to develop and test an EM which may help to reduce the recurring failures of SMEs (Nwaizugbo & Anukam, 2014; Olannye & Eromafuru, 2016). Despite the efforts made by these scholars in previous studies, the number of business failures in Nigeria, as well as the gaps in extant EM models, have called for the deductive development of the new integrative model of EM. This model was tested and analysed in this study. Initially, the integrative EM model conceptualised for this study had four orientations (entrepreneurial, market, market driving and intra-team) which encapsulated nine dimensions (innovativeness, proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, customer intensity, value creation, market sensing, alliance formation and teamwork.

Within the scope of EM, it is interesting that innovativeness shows a significant direct and negative effect on the survival of manufacturing SMEs. The ranking of EM dimensions in terms of their level of importance would note that teamwork, proactiveness, market sensing, customer intensity and innovativeness have a strong and direct significant effect on the survival of manufacturing SMEs. Resource leveraging has a moderate and direct significant effect, while calculated risk-taking and value creation have a weak and direct significant effect on the survival of manufacturing SMEs. With manufacturing SMEs predominantly in the mature and declining stages of their organisational life cycle in Nigeria, owner-manager’s proactiveness, calculated risk-taking, resource leveraging, customer intensity, value creation, market sensing and teamwork, through innovativeness, are key contributors to SMEs’ survival. These have positively and directly significant effect on the survival of manufacturing SMEs.

One of the notable contributions of this study is the conclusion that alliance formation is considered by owner-managers as an insignificant factor to SME survival despite the social capital and relations which provide bridges to resources associated with alliance formation in mature SMEs in the manufacturing sector. The three key characteristics of alliance formation include: (1) voluntary arrangements between firms, (2) the sharing or co-developing of products, technology or services and (3) exchange with alliance partners (Wörgötter, 2011; Vuuren & Wörgötter, 2013). Arguably, the significance of alliance formation varies as SMEs grow. It is possible that owner-managers of mature SMEs in the manufacturing sector have been in the business long enough to have selected and retained external and trusted alliances which are later even taken for granted. There is also a variety of barriers that dissuade mature manufacturing SMEs to enter into alliances after having survived for so long. These barriers may include the fear of abusing or misusing resources by partners as well as distrust and the risk of exposing commercial secrets. The way owner-managers interact with the market and key stakeholders such as partners in business interactions is key. It is notable that the various orientations within the EM contain four types of interactions by owner-managers which are key for the survival of manufacturing SMEs. Firstly, EO interacts with market orientation in the form of customer intensity and value creation but also the market sensing and market-driving orientations. Secondly, market orientation interacts with EO and also intra-team orientation. Thirdly, intra-team orientation interacts with market-driving orientation but also market orientation. Lastly, market-driving orientation interacts with EO and also with intra-teamwork orientation to affect the survival of SMEs.

This study has made two unique contributions to the ontology of EM and the body of EM literature. Firstly, the study has highlighted intra-teamwork as an indispensable aspect of EM, particularly for mature SMEs in the manufacturing sector. One of the gaps in the extant models of EM has been the omission of intra-teamwork. The current study has addressed this gap by illuminating the collective level of intra-teamwork for EM and the survival of manufacturing SMEs. Intra-teamwork is key not just to ensure collective efficiency for the survival of SMEs but also to sense market changes on the one hand and drive customer intensity and value creation on the other. Thus, intra-teamwork is critical for SME’s survival through generating customer satisfaction and collective efficiency. This is sensible, especially given that intra-teamwork has proved to be a major predictor of EM survival. However, this raises two essential questions: (1) Why has the teamwork dimension been ignored by scholars in their existing EM models when it is actually significant? (2) How do owner-managers neglect teamwork and actually think they would survive? These two significant questions are important for future investigation.

Secondly, market sensing is another unique dimension of EM, which has also been omitted in a variety of extant models by researchers. This study posits that marketing sensing by ownermanagers in the manufacturing sector is valuable as it influences the survival of SMEs. In pursuit of this, owner-managers are: responsive to the latent needs of their customers, promptly respond to market needs, flexible in organisational structure and facilitate market activities to address customer preferences. In the light of this discussion, Figure 1 presents the new validated integrative EM model with four orientations and their interactions as well as links to SMEs’ survival.

This study draws the attention of scholars to new EM dimensions, such as market sensing and teamwork, found in the developed and validated integrative EM model. These were not included in previous studies. Teamwork needs to form part of EM. This necessary dimension can aid any owner-manager in transforming vision and capital into reality. Similarly, market sensing is vital if the owner-manager is to understand the latent needs of his/her customers. The study also shed revealing how market sensing and teamwork are critical and indispensable dimensions of the Integrative EM model to help SMEs survive in the long term. The developed and validated new and integrative EM model explains the impacts of EM orientations/dimensions on the survival of small and medium-sized businesses in Nigeria. The adoption of this new integrative model of EM by SME owners, managers and practitioners would greatly assist in the reduction of business failure in Nigeria and around the globe. While SME owners and managers may use the EM model to devise survival strategies based on EM, practitioners, such as policymakers, may use the model to create a conducive business environment for SME survival in Nigeria. The study has also contributed a contemporary model of EM, which can be adopted by academics for further research.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This quantitative study sought to examine the effects of EM on the survival of manufacturing SMEs in Nigeria. The study has developed an Integrative EM model which could affect the survival of manufacturing SMEs. This study is an important step towards a clear understanding of EM, its dimensions and its effects on SME survival. The identified dimensions are pivotal to consider, not only for the development of SMEs in the manufacturing sector but also for other key sectors in Nigeria and beyond. The study recommends the adoption of the new integrative entrepreneurial marketing model in the management of manufacturing SMEs to aid survival.

References

Carter, M., & Tamayo, A. (2017). Entrepreneurial and intrapreneurial skills of managers as determinant of organizational performance of small and medium enterprises in Davao region, Philippines. Philippines (March 6, 2017).

Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN, 2018). Micro Finance Policy, Regulatory and Supervisory Framework for Nigeria.

Chell, E., Haworth, J. & Brearley, S. (1991). The entrepreneurial personality: concepts, cases and categories. London: Routledge.

Dimoji, F.A., & Onwuneme, L.N. (2016, January). Small and medium scale enterprises and sustainable economic development in Nigeria. In Proceedings of 33rd International Business Research Conference 4-5 January 2016.

Effiom, L., & Edet, S. E. (2018). Success of small and medium enterprises in Nigeria: Do environmental factors matter. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 9(4), 117-127.

Ene, E.E., & Ene, J.C. (2014). Financing small and medium scale business in African countries: Problems and prospects. Australian Journal of Business and Management Research, 4(6), 9.

ERGP (2017). Nigeria economic recovery & growth plan 2017-2020. Available at:http://www.mondaq.com/Nigeria/x/716720/Economic+Analysis/Economic+Recovery+And+Growth+Plan+ERGP+An+Assessment+Of+The+Journey+So+Far (Accessed on 14/05/2019).

Eziashi, J.U. (2017). Manufacturing Strategy of Firms in Emerging Economy: The Study of Nigerian Manufacturing SMEs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Northumbria at Newcastle (United Kingdom)).

Ganyaupfu, E.M. (2013). Entrepreneurand Firm CharacteristicsAffecting Success of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Gauteng Province.

Gilmore, A. (2010). Reflections on methodologies for research at the marketing/entrepreneurship interface. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship.

Gwadabe, U.M., & Amirah, N.A. (2017). Entrepreneurial competencies: SMES performance factor in the challenging Nigerian economy. Academic Journal of Economic Studies, 3(4), 55-61.

http://www.cenbank.org/Out/publications/guidelines/DFD/2018/MICROFINANCE%20POLICY.pdf

http://www.nepza.gov.ng/downloads/nirp.pdf(Accessed 11/05/2019).

KPMG, (2016). Global manufacturing outlook. Competing for growth in industrial manufacturing Retrived from https://home.kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2016/05/at-a-glancekpmgs-global-manufacturing-outlook (Accessed 11/05/2019).

Lusch, R.F., & Vargo, S.L. (2014). Service-dominant logic: Premises, perspectives, possibilities. Cambridge University Press.

Malik, A., Teal, F. & Baptist, S. (2002). The performance of Nigerian manufacturing firms: Report on the Nigerian manufacturing enterprise survey. A Research Study Supported by United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), Nigerian Federal Ministry of Industry and Centre for the Study of African Economies, Department of Economics, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Manyika, J., Sinclair, J., & Dobbs, R. Manufacturing the Future: The Next Era of Global Growth and Innovation/McKinsey Global Institute (MGI). November 2012. URL: http://www. nist. gov/mep/data/upload/Manufacturing-the-Future. pdf (18.11. 2014).

http://www.cenbank.org/Out/publications/guidelines/DFD/2018/MICROFINANCE%20POLICY.pdf

http://www.nepza.gov.ng/downloads/nirp.pdf

Neneh, B.N. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurial characteristics and business practices on the long term survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) (Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State).

NIRP. (2014). Nigeria industrial revolution plan, Rertived from https://www.nipc.gov.ng/product/nigerian-industrial-revolution-plan-nirp/

Nwaizugbo, I.C., & Anukam, A.I. (2014). Assessment of entrepreneurial marketing practices among Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Imo State Nigeria: Prospects and challenges. Review of Contemporary Business Research, 3(1), 77-98.

https://home.kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2016/05/at-a-glancekpmgs-global-

Olaniyan, T., Ogbuanu, B., & Oduguwa, A. (2017). Effect of entrepreneurial marketing on SMEs development in Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Studies in Business Strategies and Management, 5(2), 40-60.

Olannye, A.P., & Edward, E. (2016). The dimension of entrepreneurial marketing on the performance of fast food restaurants in Asaba, Delta State, Nigeria. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 7(3), 137-146.

Ooko, P.A. (2013). Impact of teamwork on the achievement of targets in organisations in Kenya. A case of SOS children’s villages, Eldoret (Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi).

Rasheed, K.O., Gbenga, O.G.U.N.L.U.S.I., & Aduragbemi, A.C. (2016). Entrepreneurial marketing and SMES performance in Lagos State, Nigeria. Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 2(1), 98-101.

Rezvani, M., & Khazaei, M. (2013). Prioritization of entrepreneurial marketing dimensions a case of in higher education institutions by using entropy. International Journal of Information, Business and Management, 5(3), 30.

Taghipourian, M.J., & Gharib, Z. (2015). Entrepreneurial marketing in insurance industry, State or private? Compare and prioritize. International Academic Journal of Business Management, 2(12), 1-10.

Uchegbulam, P., & Akinyele, S.T. (2015). Competitive strategy and performance of selected SMEs in Nigeria.

United Nations Industrial Development Organization UNIDO. (2013). Emerging trends in global manufacturing industries. UNIDO, Vienna.

Worgotter, N. (2011). Measurement model to assess market-driving ability in corporate entrepreneurship (Doctoral dissertation, University of Pretoria).