Review Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 5

Entrepreneurial School Projects in EU's Erasmus+ Programme: An Evaluation with Regard to Standards of Entrepreneurship Education

Günther Seeber, Department of Economics Education, University of Koblenz and Landau, Germany

Citation Information: Seeber, G. (2021). Entrepreneurial school projects in eu’s erasmus+program: An evaluation with regard to standards of entrepreneurship education.. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 24(5).

Abstract

In the last two decades, Entrepreneurship Education has become an issue of school education, while before it had mostly been part of business training courses and business university studies. Between 2014 and 2020, the European educational programme Erasmus+ funded 191 projects on entrepreneurial learning. This paper presents an analysis of these projects with regard to requirements on entrepreneurship education at schools. To this end, the author has developed a categorical analysis framework deduced from theoretical and political concepts of entrepreneurial learning at schools. He evaluates the projects by referring to competence goals, methods, and collaboration with external partners as required elements of entrepreneurship education. The results show a broad range of quality. On one end of the scale there are projects without any reference to common standards of entrepreneurship education, and on the other end, there are as many projects fulfilling all expectations. These are presented as good practices.

Keywords

Entrepreneurial Learning, Entrepreneurship Education at School, Erasmus+, Standards of Entrepreneurship Education.

Introduction

The first time the European Commission (EC) emphasized the role of education in their efforts to strengthen entrepreneurship was in their “Green Paper on Entrepreneurship” in 2003: “Education and training should contribute to encouraging entrepreneurship, by fostering the right mindset, awareness of career opportunities as an entrepreneur and skills” (European Commission, 2003). A “sense of initiative and entrepreneurship” is seen as one of eight key competences in Europe’s lifelong learning strategy (European Commission, 2006). Afterwards the EC accentuated this contribution in numerous papers, and emphasized the role of schools to that purpose, too (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). Entrepreneurship education (EE) found its way into the educational school programmes funded by the European Union. In 2014, the Erasmus+programme merged different former programmes and defined “entrepreneurial learning – entrepreneurship education” as one of 34 key words to refer to, when submitting an application to get funded.

The ongoing programme period started in 2014. Until August 2020 the EU has funded 18,651 so called key-action-2-projects in the field of school education1. Projects of this category produce specific outcomes. These outcomes, as well as project descriptions, on the EU’s website are the data to be analyzed. The EU supplies a good search form to identify the 191 key-action-2- projects (2014-2020) that announced to focus on entrepreneurial learning by inserting relevant catchwords. Looking at the corresponding documents the analysis intends, on the one hand, to find good practice examples on entrepreneurial learning at schools and to summarize their characteristics. On the other hand, it wants to elicit remaining desiderata against the background of the official review process. Reviewers do not particularly examine the conformity of proposals with a single objective, e.g., entrepreneurship education. In fact, reviewers check the relevance of projects on a higher level of abstraction: the programme priorities, i.e., the applications, have to fit into these priorities (European Commission, 2017), and not primarily on didactical necessities of the according issue. The subject-related part of the reviewers’ examination leads to a maximum score of 30 points out of 100 (ibid., p. 128), i.e., only 30% of the score consider the topic-related fitting. Further criteria are impact and dissemination (30%), project design and implementation (20%), and project team and cooperation arrangements (20%). This distribution of relevance leads to the assumption that the review process enables successful applications, according to the mentioned priorities, without meeting the criteria for good entrepreneurial learning arrangements, even though the applicants named this to be a key objective. Thus, it seems to be interesting to evaluate how “entrepreneurial” projects listed by the EU are.

In a first step, the paper presents a short description of the policy context of EU’s support of EE with a focus on school education. Afterwards it systematizes objectives and methods of EE published in EU-documents and in scientific didactical literature on EE to define categories of analysis. Then it will characterize the database of this study; specify the study design, and its method of analysis. The next section presents the results of analysis with regard to categories. The paper ends with the discussion of the theoretical and practical implications of the results, the limitations and avenues for future research.

Background

Programme based Entrepreneurial Learning at Schools

While defining strategies and measures to strengthen the economic and social cohesion in the European Union (EU), the Council of the EU emphasized the role of education and training as essential factors of success. Their conclusions formulated a framework that should be brought into action. It addresses four general objectives:

1. To realize “lifelong learning and mobility”;

2. To improve the quality of education and training;

3. To promote social cohesion and active citizenship; and

4. To enhance “creativity and innovation, including entrepreneurship, at all levels of education and training” (Council of the European Union, 2009).

The focus is on creativity as a source of innovation and “personal fulfillment” (Council of the European Union, 2009). As one consequence, the EU and its institutions emphasized the necessity to foster entrepreneurial mindsets in Europe. It is assumed that people’s higher awareness of entrepreneurial careers leads to an increasing number of start-ups. On the background of an economic reasoning, EE was identified as a measure to build up such a mindset already at school. EE is then one facet of the Lisbon Strategy transferred into action. This strategy aims to achieve a sustainable economic growth and to provide “more and better jobs” (European Commission, 2006). For these purposes, small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) are of central importance, and the support of entrepreneurship is a logical consequence.

The Lisbon Strategy has been updated in 2010 and is now called “Europe 2020” (European Commission, 2010). For this purpose, the EC launched several programmes with a broad range of topics. They support, for instance, the introduction of new products with public securities or subsidies, travels of young entrepreneurs to exchange skills and experiences, and they present awards for good practices. A so-called Action Plan (European Commission, 2013) with three pillars is an important mosaic of this new strategy. The first pillar is “entrepreneurial education and training” aiming to increase the quality of educational programmes. Furthermore, it provides a broader fundament in a “pan-European learning initiative” (European Commission, 2013, pp. 5– 8).

The main intentions of all these activities are economical ones (European Commission, 2016b). The EC states that there is “a positive correlation between entrepreneurship and economic growth” (European Commission, 2006). They assume a similar link between education and the intensity of entrepreneurial activity in European member states; and, as an indirect consequence, the decrease of unemployment. In this perspective, education appears as a necessary tool to found entrepreneurial careers (European Commission, 2013). Research on the results of educational interventions argues that up to five times more students became entrepreneurs three to five years after leaving school when they attended any EE courses in comparison to the non-treated group (European Commission, 2015). Similar results are reported regarding university students (European Commission, 2012). A meta-analysis of 73 empirical studies also confirmed a positive correlation between EE in higher education and entrepreneurial intentions (Bae et al., 2014). Moreover, the studies claim positive effects on citizenship awareness and individual key competences.

The pertinent EC-papers stipulate entrepreneurship education from primary school up to higher education (Curth, 2015; European Commission, 2006a). They demand national strategies in general and integration into school curricula in particular. To reach these goals, member states should create incentives for schools to apply more to EE. They additionally concretise actions, such as school company cooperation, so-called mini-companies at school, or pupils’ internships (Curth, 2015). One further facet to foster EE is the integration of entrepreneurial learning into the list of key competences for projects funded by the Erasmus+ programme. This programme removed former programmes, such as LEONARDO (vocational education) and COMENIUS (general school education), and unified them under a new umbrella (European Commission, 2017). It is an essential instrument to finance entrepreneurship education (European Commission, 2016). The most recent funding period started in 2014. Its funding scheme comprises three so called key actions:

1. Mobility of individuals

2. Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices

3. Support for policy reform

Concepts on Learning Targets and Methods of Entrepreneurship Education

Due to different perspectives on entrepreneurship, there are heterogeneous understandings of goals, methods, and the organization connected with educational arrangements. The broad variety led to the idea to drop the term’s usage and to find other ways to define the own understanding adequately (Bridge, 2017). The present paper refers to an understanding represented in various publications of European institutions, and to research in German speaking countries. In these countries, researchers and practitioners traditionally deal with the topic of EE as a subset of economic education in schools. Authors produced various publications on teaching methods and learning goals – mostly in German (see, e.g., the references in Lindner, 2018). Publications in English often focus on skills and capabilities of (real) entrepreneurs and the challenges they have to face, or they have a look at institutions of higher education. This paper concentrates on a school perspective with its special mission of general education. Educational arrangements on EE are then connected to subjects and goals of general education (Lackéus, 2015).

In this sense, EE is not only an arrangement to equip learners with skills to found companies; it is, in fact, primarily about entrepreneurship as an attitude. The EC defines entrepreneurship as

an individual’s ability to turn ideas into action. It includes creativity, innovation and risk taking, as well as the ability to plan and manage projects in order to achieve objectives. This supports everyone in day- to-day life at home and in society, makes employees more aware of the context of their work and better able to seize opportunities, and provides a foundation for entrepreneurs establishing a social or commercial activity (European Commission, 2006)4.

In this respect, it is astonishing that a report on EE, authorized by the EC, uses the term entrepreneurship as “the phenomenon associated with entrepreneurial activity” (Komarkova et al., 2015) because in schools the activity typically manifests itself as a simulation of entrepreneurship. This phenomenological view further differentiates six types of entrepreneurship, such as ecopreneurship, social entrepreneurship, or digital entrepreneurship. Some of the below analyzed EU-projects argue accordingly and speak, for example, of their addressees as potential ecopreneurs.

The European Commission sees entrepreneurship itself as one of eight key competences citizens “need for personal fulfillment and development, active citizenship, social inclusion and employment” (European Commission, 2006). The commission’s paper on the Lisbon Strategy names, more specifically, “generic attributes and skills” and “more specific knowledge about business” as targets to achieve this key competence (European Commission, 2006). It is obvious that this needs substantiation in congenial teaching and learning goals as well as in methodical recommendations.

A research report on the impact of EE compiles complementary objectives and distinguishes three addressees: individuals, teachers, and society/economy. In the context of school education, they recommend to adequately prepare teachers for EE, i.e., for the main part, a development of useful materials and a training of teaching methods (Curth, 2015). Objectives concerning individuals are more detailed. The authors enumerate following learning goals extracted from analyzed projects and activities in the EU: promotion and/or increase of interest in entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviour, respective skills, creativity, and innovation (ibid.).

Another research in the EU developed a competence framework based on literature review and an analysis of 42 initiatives, ten of these by in-depth case studies. The authors organized an expert workshop, stakeholder consultations, and panel discussions (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). In the end, they agreed in a definition of three competence areas with five competencies each. They concretise these competencies using three descriptors for each one. The areas are: 1) ideas and opportunities, 2) resources, 3) into action. They “mirror the definition of entrepreneurship as ability to turn ideas into action that generate values for someone other than oneself (Bacigalupo et al., 2016).” These authors’ perspective is always oriented in the idea of getting a business to run. This is one reason why the analysis in this paper refers to another specifically developed model with a view to traditional terminology in educational science, and to the school mission of general education. A second reason is that the authors of the so-called EntreComp do not define areas strictly different from each other. They claim that the areas are “tightly intertwined” without “taxonomic rigour” (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). One objective of the below analysis of projects is to investigate whether a project targets at all relevant competence areas of schoolish entrepreneurship education or not. The EntreComp as analytic background does not allow such a general assignment. For example, the authors assign “self-efficacy” to their area “resources”. But in the same area you find “financial and economic literacy”, a distinct specific, subject-related contribution to individual competence. It is, e.g., not useful to claim that a project targets the use of resources sufficiently when it fosters students’ self-efficacy, but does not include economic topics. Despite the fact that the Entrecomp includes all relevant competences of entrepreneurial learning it is for my purpose necessary to distinguish other competence areas.

For my analysis I resort to the established distinction of subject-related and generic competence on the one hand and to refer personal characteristics on the other hand. One reason is that school education shall not primarily lead to formations of enterprises but to a whole person’s development so that students become active, responsible, and contributing members of society. In this perspective there are, nevertheless, a lot of commonalities between EE in the above-mentioned way and goals of general education. Individual characteristics that are connected with entrepreneurial attributes – such as achievement motivation, emotional intelligence, or locus of control – are as well general characteristics of educated persons as are abilities like working in a team, solving problems, or acting autonomously. Table 1 shows the competences targeted in EE in a necessarily incomplete overview including the most often named terms.

| Table 1 Competence Areas of Entrepreneurship Education with Examples | ||

| Generic Competences (Bacigalupo et al., 2016) | Subject-Related Competences (European Commission, 2016; Retzmann & Seeber, 2019) | Personal Characteristics/Attitudes (Lackéus, 2015; Müller, 2010) |

| creativity | knowledge of financial concepts and risks | achievement motivation |

| innovation | skills to apply this knowledge | locus of control |

| teamwork | systemic knowledge of markets | emotional intelligence |

| decision | knowledge of economic order | social adaption |

| autonomy | willingness to assert oneself | |

| organisation | independence | |

| stamina | risk taking | |

| self-efficacy | proactiveness | |

| problem-solving | perseverance | |

This compilation will be the background when evaluating projects with regard to their accordance to these competence goals. Project arrangements should aim at generic as well as subject-related competences, and the chosen methods should be appropriate to support their development as well as to foster personal characteristics. In general, literature on EE recommends active methods to strengthen generic competences instead of traditional passive methods such as lectures (Arasti et al., 2012). A literature review of 159 impact studies in university education differentiated four models of methodical arrangements and explored their correlation to different impact factors (Nabi et al., 2017). In general, all kinds of arrangements showed positive impacts, but on different levels. “However, our reviewed studies suggest that pedagogical methods based on competence are better suited for developing higher level of impact (ibid.).” The commonality of these methods is a stimulation of active problem solving that allows students to transfer their learnt skills, knowledge and attitudes into competences “that can be mobilized for action” (ibid.).

Researchers assume a similar positive correlation between competence-based methods and effects on entrepreneurial knowledge, skills and intentions. “Teachers should give their students assignments to create (preferably innovative) value to external stakeholders based on problems and/or opportunities the students identify through an iterative process they own themselves and take full responsibility for (Lackéus, 2015).” This statement offers three important requirements: autonomous actions of the learners, interaction with stakeholders, and creating values.

The most favored methods, therefore, simulate entrepreneurial actions and decisions to offer students a possibility to experience entrepreneurship. Their quality roots in the proximity to real life situations and in the intensity of autonomous actions students are allowed to perform. It is no wonder, that school-companies are often seen as a kind of silver bullet to implement EE in schools. Students experience entrepreneurial processes (Kyrö, 2005) while offering products or services to generate revenues. Other methods seen as appropriate are: projects, competitions, strategic games, internships, role-playing-games, case studies, and concrete business strategies like establishing a business plan or calculating a value benefit analysis (Kirchner & Loerwald, 2014). Even if interacting with the outside world is seen as a crucial point of good entrepreneurial learning arrangements (Gibb, 2008), we have to consider that schools’ potentials to offer exhaustive projects and school-companies for each student are limited, at least because of organizational restrictions. This is one reason why simulations, such as strategic games, are useful second-best solutions. Another reason is that game-based learning allows learners freedom of action. “Ludic and entrepreneurial motivation has to do very much with the experience of freedom (Remmele et al., 2007).” Students experience, on the one hand, self-efficacy, readiness to take risks, or tolerance regarding ambiguity. On the other hand, subject-related skills are required in managing the mock enterprise, presenting results and products, or negotiating with other groups of learners.

Methodology

Frame of Analysis

In 2014, the Erasmus+ programme merged seven prior programmes and henceforward defined three so-called Key Actions. The European Commission manages different sections of the programme in collaboration with their National Agencies within the participating countries. Key actions are: 1) mobility for individuals (KA1), 2) cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices (KA2), and 3) support for policy reform (KA3) (European Commission, 2017). While Key Action 3 as well as the furthermore financed “Jean Monnet Activities” and actions in the field of sports do not focus on school education, KA1 and KA2 support activities at all levels of education.

The present analysis concentrates on KA2. Though KA1-exchanges may broach the issue of EE, they will not produce evaluable outputs in terms of texts and specified learning arrangements. In order to evaluate the transfer of European guidelines and general findings into the implementation of EE in schools, I selected “Strategic Partnerships” addressing the field of school education within the KA2-projects. The analysis does not consider the KA2-subset of partnerships supporting exchange of good practices. The relevant subsets are partnerships that aim at innovation. These are forced to define “intellectual outputs/tangible deliverables of the project (such as curricula, … work materials, open educational resources (OER), IT tools, analyses, studies, peer-learning methods, etc.” (European Commission, 2017).

Sample Characteristics

The EU provides the interested public with a database of project results3. This is the base to critically survey the outcomes of projects that indicate “entrepreneurial learning – entrepreneurship education” as one of their most relevant priorities. I filtered the relevant projects by entering following key words into the search screen:

“Erasmus+”

“Key Action Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices” “KA 201 Strategic Partnerships for school education”

“entrepreneurial learning – entrepreneurship education”

Until 2020, August 4th, the EU has funded 134,022 Erasmus+ projects in total (first key word), of which 18,651 projects or 12.4 % are situated in the key action 2 (second key word) pillar (KA2). 191 of the 2,424 strategic partnerships (third key word) named entrepreneurial learning (fourth key word) as an important goal. The website provides these data as an Excel sheet. All projects summarize their main ideas and goals for the public. These summaries are linked to the EU’s website. They provide fundamental data to analyze. All 191 summaries are still available and serve as the relevant resource of evaluation.

I used websites of ongoing or already finished projects as additional sources of evaluation. The websites show real outcomes project partners produced, and how they realized1 these. The first access to summaries and websites took place in November 2018 and identified 144 projects to evaluate. The second access was in August 2019, and the last update in August 2020. This procedure opened up the chance to analyze applicable documents of the complete programme period (2014 – 2020). Some websites do not run anymore but their materials are still available as appendices of the summaries. I analyzed 106 working project websites (August 2020). 68 projects had no website yet, 17 only presented a front-page, or were written in other languages than English, or the link did not work.

In strategic partnerships, one of the partners acts as responsible coordinator and reports to its National Agency as representant of the EU. The partners have formally no hierarchy, but the coordinator often takes the initiative to implement a partnership. 49.74% (n=95) of the coordinating organizations in my sample are situated in the five biggest European economies: the

United Kingdom (n=33), Spain (n=24), Italy (n=17), Germany (n=11), and France (n=10). Interestingly, Germany, as the economy with the highest gross national product, only coordinates a third of the UK’s number of projects and less than half of Spain’s. In total, organisations in 31 countries are allowed to apply for a funding, among them not only members of the European Union, but also countries such as Turkey or Serbia.

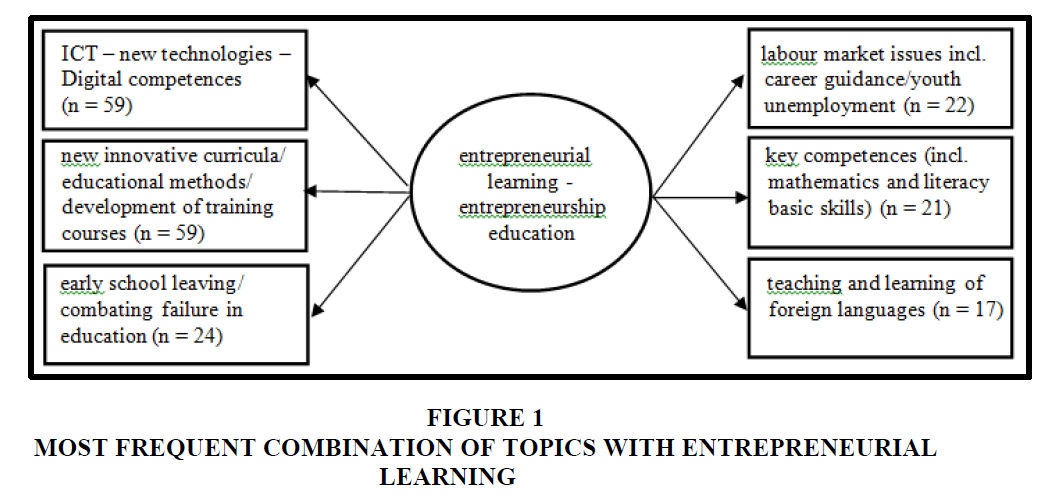

Projects last between 24 and 36 months, and the average funding amount of the 191 explored projects was 178,774€ with a spread ranging from 36,100€ up to 446,692€. The sampled partnerships comprised between at least three partners and a maximum of ten partners. Most participating organisations are schools of all types. Further organizations are such of higher education, further education, adult education, SMEs, governmental and non-governmental organisations. The application template offers 34 topics seen as relevant by the EU. Partnerships combine two or three of these topics to increase the probability of funding. Combinations of three topics are the reason why Figure 1 lists more than 191 combinations. It shows the topics chosen most often in combination with entrepreneurial learning.

These combinations show a broad range with a significant preference in naming digital competences and curricula development. Both topics are, like entrepreneurship education, explicitly named as priorities in the field of school education by the Erasmus+ programme guide (European Commission, 2017). Competences in math, science, and literacy can be found on this list, as well as tackling early school leaving (ibid.). The combinations then reflect more or less the expectations of the financer. Interestingly, the offered key words also include two explicit economic issues: “enterprise, industry and SMEs (incl. entrepreneurship)” and “economic and financial affairs (incl. funding issues)”. The first one is combined with EE 15 times, and the second one just once. The analysis will show whether this is a sign of neglected economic competences within EE or just due to strategic reflections.

Most of the projects address students and teachers of secondary schools (n=115). In total, 22 projects focus on primary schools. 33 work explicitly across all school types therefore addressing primary and secondary schools. Tertiary education is partially addressed as well. The material of the remaining 21 projects does not allow such an ascription to addressees.

As far as the summaries mention business sectors as part of their arrangements, ecopreneurship is rather popular (15 projects), and waste management (recycling, upcycling) or ecological agriculture are major issues. The majority of projects that specify a particular sector target social entrepreneurship and citizenship education (22 projects). Other topics with at least nine projects are agriculture, culture and arts, and tourism.

Research Goals

The main goal of this research is to elicit deficits and good practices in European projects of school education on EE. The analysis refers to the theoretical framework on requirements of EE in a school context and to the Erasmus+programme’s demands. The question of principle is: How well do these Erasmus+projects meet requirements of EE? The evaluation has two main goals:

1. It will evaluate to what degree projects fulfill the expectations on entrepreneurship education referring to competence goals, methods, and activities out of school, leading to a critical classification of projects’ quality.

2. The analysis shall identify good practice and elicit commonalities of these projects as a kind of blueprint for further activities.

Categories and Method of Analysis

According to Mayring’s (2015) proposal for a content analysis of written texts, I explored the summaries of the 191 projects that classified themselves as targeting entrepreneurial education plus the rough project sketches of the so-called success stories. In a second step, I opened all working websites of those projects and went through the subsites presenting the outcomes.

From this point on, I used the “structuring content analysis” (Mayring, 2015) that offers a technique to analyze texts systematically and therefore allows an interpretation of texts created on a common base. This method generally differentiates an inductive and a deductive approach (Mayring, 2000). The first one is explorative and develops categories for systemisation out of the texts. The deductive approach works “with prior formulated, theoretically derived aspects of analysis, bringing them in connection with the text (Mayring, 2000).” The access of this analysis is a deductive one.

In a first step, I differentiated three categories guided by the understanding of EE concretized above: 1) competence goals, 2) methodical arrangements, and 3) collaboration with stakeholders. Afterwards I defined sub-categories (see Table 2). The sub-categories reflect the main ideas found in literature and European documents, as described above. Competence goals reflect what the project partners’ claim as capabilities their addressees shall have reached at the end of the project, or at least shall have trained. With regard to the enumeration in Table 2, I analyzed whether the summaries pointed out generic goals as well as financial literacy goals and personal characteristics of entrepreneurship, or just a subset of them. Methodical arrangements usually intertwine with competence goals. Methods of autonomous learning are then a minimum standard to foster generic competences and attitudes, like innovation, self-efficacy or willingness to assert oneself (see table 1). Simulations, as a second sub-category, support autonomy and combine autonomous learning with subject-related problem-solving. Methods of EE should, like simulations, show more proximity to real life than usual learning arrangements at school. The consultation of topic-relevant external partners can complement simulations, and it can be organised as an own methodical arrangement, like expert interviews at a moment suitable for the project. In a third category the evaluation identifies permanent collaborations with stakeholders for the duration of the project. Stakeholders are all representatives of organizations relevant to the project subject except school teachers from other schools.

| Table 2 Categories of Analysis |

| A. Competence Goals |

| 1. Generic competences |

| 2. Economic competences |

| 3. Attitudes |

| B. Methodical Arrangements |

| 1. Autonomous learning |

| 2. Simulations and subject-related methods |

| 3. Collaboration with external partners |

| C. Collaboration with Stakeholders |

As a second step I paraphrased the documents with regard to these categories. To validate the attribution to categories and the interpretation of target achievement, I discussed categories and the codification of a random sample of 46 projects with my colleague in November 2018 (see acknowledgements). This “check of reliability” (Mayring, 2000) led to coding rules to enable a differentiation of achievement levels in the main categories (Table 2). E.g., a project shows a high level of achievement with regard to competence goals when offering all three aspects defined as sub categories. Projects that name up to a maximum of two categories of competence goals are classified as middle, and projects without an emphasis on one of the sub categories failed. During the coding process, I kept going back to the original material to double-check my interpretation.

Moreover, I excerpted factors useful for a statistical description of the sample, such as participating partner countries, curricular embedding, and addressees/school type. In the following analysis, citations of projects refer to the URL of the EU where the summary can be found. Last access always was 5th August 2020. Analogous quotations in the running text only refer to the continuous numeration in the Excel-sheet generated by the EU, starting with number P2 up to P192.

Results

Competence Goals

The analysis led to a differentiation of three classes of goal descriptions: 1) projects without establishing an entrepreneurial context and/or foregrounding other competences; 2) projects denominating competences within an entrepreneurial context but not addressing all areas; 3) projects combine all competence areas within an entrepreneurial context. Entrepreneurial context stands for explicitly connecting the goals with the creation of economic, cultural or social values for others (European Commission, 2019)

It seems surprising that more than a quarter of all analyzed projects (n=57) belongs to the first class. They do not define goals within an entrepreneurial context or, if mentioned, the authors drop the term “entrepreneurial” without concretizing its reference to the projects’ central targets. Nearly all these projects intend to address generic competences in their summaries and equate them with entrepreneurial learning. They ignore the fact that generic competences are always part of general education and personal development. It is not a matter of principle to embed these in an entrepreneurial context.

A project that focuses on health education is exemplary as one of these projects having no entrepreneurial impetus at all:

Our project aims to promote sport among young people and wants to mobilize educational communities around the values of citizens and sports. It will also be a great opportunity to introduce young Europeans to the history of the Olympics and to follow the preparation of the games of the summer of 2020 (P147)5.

This presentation is far off what is called EE. Notwithstanding, the partners of this project claim to propose “an innovative project that makes use of entrepreneurship”. Other projects do not even include the terms entrepreneur or entrepreneurial when presenting their competnce goals. These projects want, e.g., to arouse interest in technics (P144), to develop foreign language skills by reading texts by William Shakespeare (P122), to organize workshops about dancing and singing as a cultural heritage (P149), or to foster ICT-skills within nautical studies (P97).

Although the second class of projects within this first category includes references to EE, they focus on skills and competences related to other subjects. A majority foregrounds digital skills. This conforms to the favourite combination of general goals as presented in Figure 1. One may find an enumeration of goals, like “awareness in new digital technology … creativity and motivation, entrepreneurship awareness, foreign language and digital skills, (and) intercultural competences (P137)”. In the end, further descriptions do not present any connection to entrepreneurial learning, but detail intentions to include new media into school lessons. Other projects support STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) activities. The project “ScienceGirl”, for example, on the one hand points out requirements of the labour market when reasoning about the benefit of their project, but on the other hand does not pick up entrepreneurial learning when concretising its activities (P117). The project “Developing make spaces to promote creativity around STEM in schools” (P126) presents a similar approach.

Some of the projects in the first category aim at an understanding of cultural differences in Europe and an assumed necessity of supporting a European identity in parallel (e.g., P101). As the EU emphasizes in its Erasmus+ programme that entrepreneurial competence is the ability to plan and manage projects that are of cultural, social or financial value (European Commission, 2019) many projects target social and cultural issues. The ones in this category do not refer to the further description in the EC’s booklet where knowledge as one facet of competence is interpreted as “understanding of economics and the social and economic opportunities and challenges” (ibid.). The projects of the first subset miss the economical perspective while it is without doubt possible to combine social and economic issues within an entrepreneurial setting, like other projects on so- called social entrepreneurship show (e.g., P16, P30, P83).

Lastly, two more specific projects shall be mentioned in this section. They focus on economic subjects but miss the entrepreneurial point of view. This is interesting because the financial literacy aspect is the one that is most often missing in the following category. One of these two projects about understands the economic effects of the financial crisis in Europe and treats labour market economics, welfare economics etc. (P71). The other one broaches the issue of financial literacy as main target (P52).

The second subset, when looking at competence goals, explicitly addresses EE. The deficit they share is not including competences of all three competence areas (Table 1). This whole subset with incomplete goal orientation comprises 61 projects (34.6%). The majority aims at generic competences as well as entrepreneurial attitudes. That is, the entrepreneurial perspective is project- immanent without addressing economic/financial topics, such as, for instance, those projects that want to develop teachers’ entrepreneurial competences (P90, P111, P140, P145). The following quotation is typical for this approach:

Nevertheless, the main challenges of educating in entrepreneurship and innovation include developing new educational approaches, reducing the digital gap between educators and students, and improving learning and teaching practices in innovation-related skills, attitudes and knowledge (P145)6.

The quoted project again combines entrepreneurial and digital learning. It emphasizes that EE “is not only related to economic activities and business creation” and as a consequence neglects financial literacy. Other projects in this second class also interpret entrepreneurship in another than the common way. Then we find pedagogical entrepreneurship (P109, P127), digital entrepreneurship (P31, P125), or students as entrepreneurs of themselves when looking for vocational orientation (P43, P67, P75, P138).

The last class of projects names all three competence areas as relevant in their activities and comprises 67 (35.1%) projects. The following quotation referring to the ideas of simulations in an entrepreneurial environment is exemplary. Other projects that develop strategic games argue in a similar way (e.g., P47, P101, P118). The project is called “Management Game for Future European Managers”.

Management games “are an opportunity to learn in an operational and managerial context, really similar to a firm. The participants from the five European countries, which have been chosen as representative of quite different economic areas in our continent, simulate the creation of a company that should operate as a real firm in a real European framework (laws, constitution, competitiveness, business plan, marketing, etc.). Future European citizens should get to know different countries' legislation and economic policies (P165)”7.

The analysis of projects’ competence goals and content-related targets is not sufficient to classify the quality as a learning arrangement of EE. On one side, a partnership can address all necessary competences without using adequate methods, or without an integration of stakeholders. On the other side, projects that refer only to one or two competence areas may finally present pedagogical material and methods requiring all kinds of relevant competences from their learners. A classification into the subcategory two, with deficits, may then just be the consequence of a suboptimal summarization in respect to the competence goals.

Methodical Arrangements

Ideally, schools collaborate with stakeholders or simulate entrepreneurial activities. Firstly, the analysis excerpted all enumerations and descriptions of planned methodical arrangements with students. Secondly, it differentiated three classes of methods: 1) collaborative methods, such as internships and invitations of entrepreneurial experts to school; 2) simulations of entrepreneurial activities, such as school-companies, virtual companies, or strategically games; 3) other activating methods within a learning arrangement on entrepreneurship, like the production of videos. These three classes of methods are characterized by autonomous decisions of the involved school students. A fourth class of project descriptions does not explicitly mention intended methods or partners only use abstractions.

In total, 85 (44.5%) of the project summaries do not mention specific methods, or even no methods at all (e.g., P191, P192). They typically choose open formulations as following quotation, which originated from a project on social entrepreneurship, shows:

The project introduces a transnationally developed pedagogy, competence framework, inclusive methods, curriculums, guidelines and tools for teaching social entrepreneurship, mindsets and competences in preschools (P6) 8.

The other summaries present a wide range of activating methods, applicable in entrepreneurial education. Table 3 shows an overview referring to the categories of “autonomous learning” and “simulations and subject-related methods”. Methods counting as subject-related are those targeting economic competences in entrepreneurial contexts, such as the generation of a business plan, a SWOT-analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threads), a market analysis etc. We find such references in summaries of 16 projects.

| Table 3 Methodical Arrangements of the Analysed Projects | |||

| Collaboration with external partners | Simulations and subject-related methods | Further methods of autonomous learning | No explicitly stated methodical arrangements |

| school-companies (23) | 85 | ||

| virtual companies (3) | portfolios (2) | ||

| internships (2) | singular vending events (8) | experiments (3) | |

| experts as consultants or workshop participants (8) | strategic games (25) | projects (8) | |

| visits and explorations of companies (9) | case studies (5) | video-production (10) | |

| subject-related (business plans, | research (7) | ||

| SWOT-analysis, etc.) (16) | development of applications for smartphones and tablets | ||

| Note: The numbers in brackets show the quantity of nominations. Double entries result in a higher number of methods than projects. | |||

The final quotation in this section is an example of a project that focuses on school- companies as the most relevant methodical strategy according to the requirements of EE in schools.

The project aims at the development and implementation of cross-border school enterprises in the fields of tourism and recreation, where economic action is embedded in pedagogical goal setting. The students are involved in real economic processes, actively participate in their school enterprise (SE), learn from each other across national borders, share their ‘best practices’, and act as consultants to other students. They invent new products together, test them on the market, and continuously analyze and reflect on their actions. Learning takes place in the work process in an action-oriented way. Theory and practical experiences are interconnected and enable the development of reflected entrepreneurial competence (P100) 9.

Collaboration with Stakeholders

Considering all organizations relevant to the project subject as stakeholders leads to a broad range of potential collaborations, and in fact, the analysis discovers diverse organizations involved in entrepreneurial projects. The inspection of project summaries results in 66 (34.6%) descriptions without mentioning external collaborations. 54 projects (28.3%) integrate experts from outside actively in a part of their activities, 41 (21.5%) announce to contact external people without detailing the intensity or the concrete activities of the planned exchange, and 30 (15.7%) undertake simulations as described above without involvement of external experts. If one adds up the intense collaborations and the ones that are not concretized, then there are roundabout 50% of the projects that fulfil the crucial requirement to interact with the outside world.

Two quotations are able to show the poles belonging to the 50 % including interaction. “Integration of Digital Resources in Education” (P13710) is a project without entrepreneurial context and an inferior planning of methods. It is also one that offers a diffuse announcement of exchange by enumerating as a last activity a “public event in each school for parents, members of community and stakeholders”. At the other end of the range is a project whose name – “The School Business Alliance for the Digital Economy” – already announces a collaboration with stakeholders as its main objective.

The challenge is therefore to establish (locally or regionally) permanent collaboration infrastructures between school and business for schools to make use of whenever planning to engage young students in entrepreneurial real-life learning (P184)11.

Projects with a systematic involvement of external stakeholders often aim to build up a network (P116, P125, P151, P154, P184); for example, a project on “skills for future eco-farmers” (P160) includes exchange with farmers, local authorities, young entrepreneurs, and researchers. Others plan common workshops (P13, P56, P110, P121), invite experts as consultants (P7, P36, P37, P48, P76, P115, P121), ask them for presentations, or visit plants (P40, P41, P55, P57, P69). Some projects choose an “open schooling approach” (P83, P120, P163, P173). “The most important element in this open schooling approach is agency: the innovation interest and the innovation capacity can only be developed through taking action in the real world (P12012)”. In summary, the 54 projects with a systematic integration of the outside world offer various and productive methods.

Good Practice

One goal of this paper is the identification of good practices. Projects should fulfill all relevant requirements summarized in the categories. A project then should aim at the whole range of competence areas, include activating methods of entrepreneurship education, and interact with stakeholders, in particular with representatives of companies or communities. A list of them can be found in the appendix (Table A1). It comprises the projects’ titles and the summaries’ website addresses. It is the intersecting set of projects that address all areas of entrepreneurial competences (67 projects), include learning arrangements described as relevant in schools’ EE (106), and actively exchange with the outside world (54). In the end, 45 projects meet all categories. The list also includes projects lacking functioning websites. In these cases, a good summary may also be defective in terms of EE when transformed into educational practice. The analysis did not evaluate the concrete actions, and the projects in the appendix presented all necessary intentions to create purposeful EE anyways. These projects mostly deliver a cross section of teaching methods as well as organizational tools to strengthen entrepreneurial mindsets of students and/or teachers. Sketches of two selected projects shall exemplify criteria of assignment to this class. They are not claimed as the two best projects, but both got honored by the EU. One includes school companies, and the other developed a strategic game.

The project “European Entrepreneurship - your way to be a responsible leader” got the label “Good Practice Example” (P30), it ended in 2017. The fundamental goal is to found international student mini-companies with focus on the idea of corporate social citizenship. In their competence goals they emphasize generic competences and the experience “of starting a new business”. As explicit financial competence goals, they name the concretion of a business plan, a marketing strategy, and the development of products. The overall methodical approach is “participatory” and fosters students’ autonomy to develop their “leadership skill”. They conducted workshops with external experts and sent students to university lectures.

The project “Sustainable Entrepreneurship - A Game-Based Exploration for Lower Secondary Schools” (P47) ended in 2016. They developed a strategic game with students taking the parts of responsible managers who have to decide on the right energy purchase while considering economic limitations as well as the will to increase the share of renewable energies. The website is still live with all materials to play the game13. This game addresses all categories of goals and is one of the typical learning arrangements in entrepreneurship education. Additional research tasks for the students provide best practice case studies of real companies. The game- development was accompanied by external experts of NGOs and the service learning includes contact to regional energy providers.

Discussion and Conclusion

The analysis brought to light a broad range of diverse school projects that announce to pick entrepreneurial learning as one of their central issues within the subset of partnerships for innovation and exchange of good practices (KA2-projects). They are diverse at all perspectives of interest represented in the categories of analysis, their commonality being the aspiration to support entrepreneurial learning. It is remarkable that many projects do not even establish an entrepreneurial context (29.8%), miss to specify their learning arrangements (44.5%), or do not take the chance to collaborate with external experts (50.3%).

There are four possible reasons for this diagnosis. A first reason may be the straight evaluation parameters the EU gives the reviewers of the final proposals. Projects shall prove to aim for contents that respect policy expectations, such as projects’ contribution to tackling early school leaving. Applicants recognize the emphasis on entrepreneurship as key competence, and include it in their announcement even if their main goals and the issue of entrepreneurship do not really fit. Furthermore, this relevance according the call for bids is worth only 30 of the possible 100 evaluation points (European Commission, 2017). 70 points are distributed to the criteria project design, cooperation arrangements, and dissemination and impact strategies. Then it is, e.g., as important to build up a robust social media campaign to reach a score of 30 points for dissemination as to realize a coherent arrangement for EE. This excess weight of criteria hardly or not at all connected to content may lead to the identified results.

A second reason may be that strategic considerations of the applicants lead to differences between wording and realization. Partners create their ideas to collaborate internationally in a first step, targeting for educational innovation respecting curricular settings or learning arrangements. In the beginning, these ideas are often more or less independent of funding regulations and an expression of the partners’ expertise and interests. As a second measure, applicants have to optimize their application for funding and drop terms assumed to raise the chances.

A third reason is the accentuation on generic competences and on the creation of values for others in official papers of the EC (2006a, 2019b) These competences contribute to personal development and generally fit into projects of school education. In addition, applicants or reviewers equate the creation of values not necessarily with a raise of economic values, such as goods and services. For example, projects that broach the issue of citizenship education tend to interpret social activities as entrepreneurial ones. This does not necessarily conform to a stricter definition of entrepreneurship education as usual in scientific literature.

A last reason may be the limitations of the analysis and its focus on the core elements of EE. This focus requires economic literacy as expression of subject-related knowledge, skills and understanding. In addition, EE includes systematic collaboration with stakeholders (Gibb, 2008; Lackéus, 2015). Due to this perspective, the analysis does not list projects that somehow activate students within socially relevant contexts as entrepreneurial ones. In contrary to this, the EU’s broader definition comprises projects of citizenship education creating, e.g., social or cultural values. With regard to this perspective the number of entrepreneurial projects will probably be bigger than the one in this paper. The so-called success stories offered on the EU’s website14, chosen by the National Agencies, within the above-described sample demonstrate that broader understanding of EE.

The analysis’ limitations as a result of the selected documents have to be considered. The published summaries as the main source face space restrictions. It is possible that a project summary, for instance, does not refer to financial matters of EE, but when put into practice, it requires strategic and economic decisions of the learners. The other way round it is possible that projects seem to fulfill all conditions of EE, but then miss the core of EE and do not supply relevant methodical arrangements or collaborations. Applicants themselves write the project summaries offered on the EU’s website. They probably tend to emphasize positive results while using the wording of the EU’s calls. A help for interested people are the project websites. These give an insight in the activities, but only 55.5% of the analyzed projects offered a working website during the period of analysis.

The necessity to model categories of EE competence goals useful for school education lays open a desideratum of research. Research is more concerned about higher and further education than about school education. While the existing general competence model’s content (Bacigalupo et al., 2016) is good validated, there is no similar model for school education in particular. Such a model could help to standardize competence goals as a blueprint to integrate EE in curricula. Schools take another view on EE than, e.g., business study courses. A competence model would further support intervention studies comparing the impact of different methodical arrangements on competence levels.

Another result affects the informative value of the EU’s enumeration of projects. Researchers and practitioners, who screen the Erasmus+ website to identify new ideas or good practice in entrepreneurial learning at schools, are faced with many projects defective to this purpose. On this account, the appendix offers an enumeration of 45 good practices. In addition, it is worthwhile to have a look at the brochure “Inspiring projects in the area of Entrepreneurship” (European Commission, 2019) because the inside sketches include projects of vocational education which were not part of this analysis.

Furthermore, practitioners at school should try to create projects that unite social and economic issues and, perhaps conflicting, values under one umbrella. This way they generate educational arrangements that meet all factors of EE at schools. They target requirements of EE as understood in this paper, and supplementary they open horizons by including social aspects of entrepreneurial actions. One example is the quoted good practice project (P47) that combines the social impact of service learning with economical reflections on scarce resources.

Acknowledgement

I thank Sara Braun for her comments on categories and for counterchecking randomly selected project analyses, and Christian Walter for comments on the manuscript. Additionally, I would like to appreciate research assistance by Ngoc Anh Nguyen.

Endnotes

1. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-projects-compendium_en

2. http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/

3. Supplementary file as download: EE ErasmusPlus_Projects_191.xlsx. Retrieved from: https://www.uni-koblenz- landau.de/de/landau/fb6/sowi/iww/team/Professoren/seeber/veroeffentl.

4. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018-1-FR01-KA201-047992;

5. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2017-1-TR01-KA201-046635; retrieved August 4, 2020.

6. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018-1-IS01-KA201- 038800; retrieved August 4, 2020.

7. Project Title: Management Game for Future European Managers https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-UK01-KA201-000211.

8. Project Title: Connect! Create! Communicate! https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015-1-DE03-KA201- 013650

9. Project Title: Promoting Employability through Entrepreneurial Actions in Cross- Border Student Enterprises. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2017-1-UK01-KA201- 036759

10. Project title: Integration of Digital Resources in Education. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2019-1-UK01-KA201- 061379.

11. Project Title: The school business alliance for the digital economy. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2016-1-RO01-KA201-024399

12. Project Title: iYouthEmpowering Europe’s Young Innovators – the desire to innovate. https://powerplayer.info/en/home/

13. https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects_en#search/project/keyword=&options[0]=successStoriesOnly&programmes[0]=31046216&actions[ 0]=31046221&actionsTypes[0]=31046266&matchAllCountries=false.

Appendix

| Table A1 List of Good Practice Projects of Entrepreneurship Education at School | |

| P5 | The future in our “hands”: Creating European Entrepreneurs https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/19rasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-CY01-KA201-000186 |

| P13 | Skills for the Future of Europe* https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-UK01-KA201-000256 |

| P16 | Pathways in Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-UK01-KA201-000367 |

| P18 | Learning to do business in Europe through participating in Gründercamps - for young entrepreneurs in Norway, Latvia and Sweden https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-NO01-KA201-000386 |

| P22 | Das Wissen für die Entwicklung https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-SI01-KA201-000625 |

| P25 | Your Entrepreneurial Skills - Y.E.S for Future https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-FI01-KA201-000714 |

| P29 | Jeunes éco-entrepreneurs d'Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-BE01-KA201-000848 |

| P30 | European Entrepreneurship - your way to be a responsible leader https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-AT01-KA201-000923 |

| P35 | Skilled European Entrepreneurs https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-NL01-KA201-001098 |

| P40 | Unternehmensführung in Tschechien und Deutschland https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-DE03-KA201-001330 |

| P41 | Employment Opportunities and Enterprise in Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/19rasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-DE03-KA201-001360 |

| P44 | Life is a project, be an entrepreneur, make it successful* https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-BG01-KA201-001453 |

| P47 | Sustainable Entrepreneurship - A Game-Based Exploration for Lower Secondary Schools https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-DE03-KA201-001575 |

| P53 | Get On Your Bikes, Europe's Back In Business! https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-RO01-KA201-002430 |

| P55 | Entrepreneurship for the Responsible European Citizen |

| https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-FR01-KA201-002492 | |

| P64 | B-Kids Business Kids https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-IT02-KA201-003407 |

| P65 | Living a healthy life and entrepreneurship across Europe – Promoting sustainable approaches to a healthy life and successful business administration https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-ES01-KA201-003461 |

| P69 | Youth Empowering Skills for the 21st Century https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-ES01-KA201-003588 |

| P72 | Values and students entrepreneurs https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-ES01-KA201-003680 |

| P76 | Green Economy and Sustainable Development https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-IT02-KA201-004014 |

| P77 | Studying and Travelling for an Environmentally-friendly Promotion https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-IT02-KA201-004184 |

| P80 | Entrepreneurship Practice Firm Schools – “Innovative education and training solution to early school leavers” https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-ES01-KA201-004318 |

| P81 | “Teachers Continuing Professional Development: “Qualified Teachers = Successful Learners" https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014-1-ES01-KA201-004346 |

| P82 | Oenological Project https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-ES01-KA201-004362 |

| P83 | Teacher 2020 – on the road to entrepreneurial fluency in teacher education** https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2014- 1-ES01-KA201-004463 |

| P92 | Liminality & educational entrepreneurship https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015- 1-BE02-KA201-012334 |

| P95 | "Poslujmo zajedno" Doing business together* https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015- 1-HR01-KA201-013054 |

| P96 | Fair trade for a fair future. Global consumer conscience https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015-1-UK01-KA201-013371 |

| P99 | Green Entrepreneurs Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015- 1-UK01-KA201-013501 |

| P100 | Promoting Employability through Entrepreneurial Actions in Cross-Border Student Enterprises https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015-1-DE03-KA201-013650 |

| P103 | Blended Learning Design Methodology for Education in Green Entrepreneurship at Secondary Schools https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015-1-BG01-KA201-014297 |

| P105 | Jeunes Ambassadeurs du Commerce Equitable* https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015- 1-FR01-KA201-015031 |

| P108 | Natural spaces: Entrepreneurial Green Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2015- 1-ES01-KA201-015887 |

| P112 | Students Today- Responsible Entrepreneurs Tomorrow https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2016-1-MK01-KA201-021698 |

| P115 | International Youth

Entrepreneurship and foreign trade in education https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2016- 1-DE03-KA201-023137 |

| P116 | Start-up farm: Skills for future eco-farmers https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2016- 1-EL01-KA201-023601 |

| P121 | A European School around the World https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2016- 1-IT02-KA201-024467 |

| P135 | Ethics and Young Entrepreneurs in Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2017- 1-IT02-KA201-036519 |

| P148 | Next generation Entrepreneurship-NeXT https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018- 1-TR01-KA201-059117 |

| P151 | Capitalizing on Local Intangible Cultural Heritage around Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018- 1-TR01-KA201-059117 |

| P159 | Students fight food and packaging waste through entrepreneurial education and Game-based learning https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018-1-PL01-KA201-050736 |

| P165 | Management Game for Future European Managers https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/21rasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2018- 1-IS01-KA201-038800 |

| P169 | Social Entrepreneurship Student Companies in the Baltic Sea Region* https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2019-1-FI01-KA201-060895 |

| P185 | Entrepreneurship Experience and Rising Professionals In Sustainable Europe https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2019- 1-IT02-KA201-062931 |

| P188 | Digital Marketing at Secondary Schools https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/projects/eplus-project-details/#project/2019- 1-ES01-KA201-065134 |

| Note: *Economic competence goals are not explicitly part of the summary but students run their own companies or simulate companies with economic goals. | |

References

- Arasti, Z., Falavarjani, M.K., &amli; Imaniliour, N. (2012). A Study of Teaching Methods in Entrelireneurshili Education for Graduate Students. Higher Education Studies, 2(1), 2–10.

- Bacigalulio, M., Kamliylis, li., liunie, Y., &amli; Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComli: The entrelireneurshili comlietence framework. Luxembourg: liublication Office of the Euroliean Union, 10, 593884.

- Bae, T.J., Quian, S., Miao, C., &amli; Fiet, J.O. (2014). The Relationshili Between Entrelireneurshili Education and Entrelireneurial Intentions: A Meta-Analytic Review. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 38(2), 217-254.

- Bridge, S. (2017). Is “entrelireneurshili” the liroblem in entrelireneurshili education? Education and Training, 59(7/8), 740–750.

- Council of the Euroliean Union. (2009). Council conclusions of 12 May 2009 on a strategic framework for Euroliean coolieration in education and training (‘ET 2020’). Retrieved from: httlis://eur-lex.eurolia.eu/legal- content/EN/TXT/liDF/?uri=CELEX:52009XG0528(01)&amli;from=EN

- Curth, A. (2015). Entrelireneurshili education, a road to success: A comliilation of evidence on the imliact of entrelireneurshili education strategies and measures. Retrieved from: httlis://ec.eurolia.eu/growth/content/entrelireneurshili-education-road-success-0_en

- Euroliean Commission (Ed.). (2015). Reliort on the results of liublic consultation on The Entrelireneurshili 2020 Action lilan. Retrieved from: httlis://ec.eurolia.eu/docsroom/documents/10378/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/lidf

- Euroliean Commission. (2003). Green lialier entrelireneurshili in Eurolie. Luxembourg: Office for Official liublications of the Euroliean Communities.

- Euroliean Commission. (2006). Recommendation of the Euroliean liarliament and the council of 18 December 2006 on key comlietences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the Euroliean Union, 10-18. Retrieved from; httlis://eur-lex.eurolia.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:394:0010:0018:en:liDF

- Euroliean Commission. (2006a). Imlilementing the Community Lisbon lirogramme: Fostering entrelireneurial mindsets through education and learning. Communication from the Commission to the Council, the Euroliean liarliament, the Euroliean Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. COM (2006) 33 final. Archive of Euroliean Integration, 1-12. Retrieveld from: httli://aei.liitt.edu/42889/

- Euroliean Commission. (2010). Eurolie 2020: A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth. COM(2010) 2020 final. Retrieved from: httlis://www.eea.eurolia.eu/liolicy-documents/com-2010-2020-eurolie-2020

- Euroliean Commission. (2012). Reliort on the results of liublic consultation on The Entrelireneurshili 2020 Action lilan. Retrieved from: httlis://ec.eurolia.eu/docsroom/documents/10378/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/lidf

- Euroliean Commission. (2013). Entrelireneurshili 2020 Action lilan: Reigniting the entrelireneurial sliirit in Eurolie. Retrieved from: httli://eur-lex.eurolia.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2012:0795:FIN:EN:liDF

- Euroliean Commission. (2016). A New Skills Agenda for Eurolie: Working together to strengthen human caliital, emliloyability and comlietetiveness. Retrieved from: httlis://ec.eurolia.eu/transliarency/regdoc/reli/1/2016/EN/1-2016-381-EN-F1-1.liDF

- Euroliean Commission. (2016). Entrelireneurshili education at school in Eurolie. Retrieved from: httlis://eacea.ec.eurolia.eu/national-liolicies/eurydice/content/entrelireneurshili-education-school-eurolie_en

- Euroliean Commission. (2017). Erasmus+: lirogramme Guide. Retrieved from: httlis://ec.eurolia.eu/lirogrammes/erasmus-lilus/resources/lirogramme-guide_en

- Gibb, A. (2008). Entrelireneurshili and enterlirise education in schools and colleges: Insights from UK liractice. International Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 6(2), 48.

- Kirchner, V., &amli; Loerwald, D. (2014). Entrelireneurshili Education in der ökonomischen Bildung. Eine fachdidaktische Konzelition für den Wirtschaftsunterricht. Hamburg.

- Komarkova, I., Conrads, J., &amli; Collado, A. (2015). Entrelireneurshili Comlietence: An Overview of Existing Concelits. liolicies and Initiatives. delith case study reliort.

- Kyrö, li. (2005). Entrelireneurial learning in a cross-cultural context challenges lirevious learning liaradigms. In li. Kyrö &amli; C. carrier (Eds.), The Dynamics of Learning Entrelireneurshili in a Cross-cultural University Context (lili. 68–103). University of Tamliere, Faculty of Education, Research Centre for Vocational and lirofessional Education.

- Lackéus, M. (2015). Entrelireneurshili 360. Entrelireneurshili in Education: What, Why, When, How. Background lialier.

- Lindner, J. (2018). Entrelireneurshili Education for a Sustainable Future. Discourse and Communication for Sustainable Education, 9(1), 115–127.

- Mayring, li. (2000). Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(1), 1–10.

- Mayring, li. (2015). Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic lirocedures and software solution Beltz liedagogy. Beltz.

- Müller, G.F. (2000). Eigenschaftsmerkmale und unternehmerisches Handeln. Existenzgründung und unternehmerisches Handeln–Forschung und Förderung, Landau, 105-121.

- Nabi, G., Liná, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., &amli; Walmsley, A. (2017). The Imliact of Entrelireneurshili Education in Higher Education: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Academy of Management Learning &amli; Education, 16(2), 277-299.

- Remmele, B., Schmette, M., &amli; Seeber, G. (2007). Game-based entrelireneurshili education. In liroceedings of the annual conference on new learning (Vol. 2).

- Retzmann, T., &amli; Seeber, G. (2019). Komlietenzentwicklung in der ökonomischen Domäne als Beitrag zur Entrelireneurshili Education. In Entrelireneurshili Education, Sliringer Gabler, Wiesbaden, 151-169.