Research Article: 2018 Vol: 24 Issue: 1

Entrepreneurship and Regional Economic Development: The Actions Of The Industrial Entrepreneurs of Caxias Do Sul, Brazil (1950-1970)

Claudio Baltazar Corrêa de Mello, University of Caxias do Sul

Eric Charles Henri Dorion, Universidade de Caxias do Sul

Vania Beatriz Merlotti Herédia, University of Caxias do Sul

Keywords

Entrepreneurship, Caxias Do Sul Metallurgy and Metal-Mechanic Industry, Regional Economic Development, Entrepreneurial Actions, New Market Creation, Structure of Social Relationship.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs are two of the most popular topics of our time, showing interest to both the academic and the business worlds (Watson, 2012). On this issue, Thornton, Soriano and Urbano (2011) argue that there is also a common perception that entrepreneurship is associated to a heroic individual or an economically successful company. However, according to the authors, this conception can be considered as a fundamental error “based on the increasing evidence showing that individuals and entrepreneurs are socially rooted in located network structures of a specific cultural context” (Thornton, Soriano and Urbano, 2011). According to Watson (2012) and due to the fact that successful businesses are the consequence of both extraordinary individuals and the variety of interests associated to entrepreneurship, “there is an almost inevitable meaning ambiguity, which raises the concern of researchers about the possibility of a serious analysis of this phenomenon, wherever it may exist” (Watson, 2012).

In an attempt to advance the quality of the empirical and theoretical work of entrepreneurship, Shane and Venkataraman (2000) draw up an integrated framework that helps researchers to recognize the relationship between multiplicities of factors necessary for the understanding of the concept of entrepreneurship. The authors argue that the concept of entrepreneurship offers questions from different areas of academic research, but most researchers are mainly occupied with the “why of things”, instead of the “how of things”. The authors wanted to know how “[the opportunities for the creation of goods and services happen or how some people and not others do discover and exploit those opportunities and use different modes of action to explore entrepreneurial opportunities]” (Shane and Venkataraman, 2000).

For Béchard (1997), the field of entrepreneurship is characterized by both the paradigms of the entrepreneurial economy and the entrepreneurial society. The author suggests that underlying the paradigm of the entrepreneurial economy, “on one hand, demonstrates the economic forces that regulate the demand for goods; and on the other hand, it enhances the forces that determine the psychological traits of the entrepreneur and the organizational forces that adapt quickly to market pressures” (Béchard, 1997). Consequently, the Entrepreneur Society is defined as both the economic forces that expand the supply of goods and the psychological forces that encourage innovative behaviour and services, which allow people to realize the opportunities for change in a society and generate social action and creative forces to create new organisations (Casson, 2013; Béchard, 1997).

Gartner (1988) believes that the search for the answer to the question “who is an entrepreneur?” which only focuses on the personality traits, will not lead to a definition of the entrepreneur, neither will help us to understand the phenomenon of entrepreneurship (Andersson, et al., 2012). The entrepreneur's personality traits are, for Gartner (1988), extensions of the entrepreneur behaviour and thus, the “research on entrepreneurship should focus on what the entrepreneur does, not on who he is” (Gartner, 1988). The author proposes a reorientation towards a behavioural approach to entrepreneurship, starting to ask how the organisations come into existence.

Therefore, considering that the field of entrepreneurship is characterized by the paradigms of the entrepreneurial economy and the entrepreneurial society and taking into account the sense of Gartner (1988) and Frese (2009) that research on entrepreneurship should focus on the actions of the individuals, this study aims to examine the actions of the industrial entrepreneurs of the region of Caxias do Sul that contributed to the economic and social development of the northeast region of Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) between 1950 and 1970.

The metropolitan region of Caxias do Sul has an estimated population of 475,000 inhabitants and it constitutes a regional reference in the State of Rio Grande do Sul for its municipal services, health services and its technical and higher education programs that reach more than 1,000,000 people. The economy of Caxias do Sul has more than 26,500 industrial, commercial and service companies, with 6,500 companies from the manufacturing sector. The regional economy employs over 180,000 workers (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 2015) and its industrial activity is mostly centred in the metallurgic and metal-mechanic sectors, as two of the most dynamics and diversified in Brazil. The manufacturing sector reaches revenue of US 5,500,000,000 and employs more than 70,000 workers (Sindicato das Indústrias Metalúrgicas, Mecânicas e de Material Elétrico de Caxias do Sul, 2015).

The 1950-1970 period was chosen because of the specific economic growth encountered in that period in the region of Caxias do Sul, where the industrial entrepreneurs incorporated a spirit of fast modernization based on the current economic development models of the 1950s up to the 1970s. It allowed them to develop and to create new businesses, to expand their businesses and to adequate them through the development of new international markets.

In a first moment, the study introduces the theories of entrepreneurship, more specifically about the economic and social dimensions of Landström, Harirch and Aström (2012), which link and rank the key academic researches, manuals and studies that represent the state-of-the-art of the knowledge on entrepreneurship. In a second moment, it introduces the theoretical research on the socio-economic conditions and the entrepreneurial activities that contributed to the economic and social development of the Northeast region of Rio Grande do Sul (1950-1970), based on the studies of Pesavento (1985), Herédia and Machado (2001), Brum (2003) and Herédia (2007). Consequently, an empirical phenomenological research was conducted to understand what happened with those industrial entrepreneurs that made the region of Caxias do Sul so prosperous socio-economically.

Literature

Entrepreneurship, New Market Creation and Economic Development

Landström, Harirch and Aström (2012) conducted a study that examined the state-of-the-art on the entrepreneurship research field. Their conclusion shows that among the 20 most important works, 13 have their theoretical foundations anchored in economical entrepreneurship and new markets creation. The key contributions presented by the authors are from Knight (1921), Schumpeter (1934 & 1942), Kirzner (1973 & 1997), Casson (1982), Rocha (2012) and Shane (2000).

Those theoretical foundations constitute different schools of economic thought, such as the ones introduced by Knight, Schumpeter and Kirzner in a first moment and an integrative one more recently presented by Landström, Harirch and Aström, (2012). Still, the authors believe that even though there is an extensive theoretical base produced on the concept, no consensus has emerged yet.

Knight (1921), entitled as “Risk, Uncertainty and Profit” and proposes a lecture of the world as uncertain and in a constant mode of change. The author makes a distinction between “calculated risk and uncertainty, arguing that opportunities arise from change and that the entrepreneur receives a return on his decisions under real conditions of uncertainty” (Landström, Harirch and Aström, 2012). The author makes a difference between uncertainty and risk by developing the concept of “true uncertainty”, which constitutes the basis of the concept of profit in the theory of competition. For Knight (1921), when a change is expected there will be no opportunity for profit (Landström, Harirch and Aström, 2012). In a social environment characterized by uncertainty, the entrepreneur is someone responsible for the economic progress associated with the technology and the organisation's business and is the expert capable of dealing with uncertainty.

In the Theory of Economic Development (1934), Schumpeter introduces the economic development as a dynamic structural process of change driven by innovation. According to the author, this development is characterized by the implementation of new combinations, where the entrepreneur is required in boosting change and promoting economic growth through the production of those new combinations.

The creative innovation of the entrepreneur is for Schumpeter (1934 & 1942) an endogenous cause of change and development in an economic system. The way that the entrepreneurs recognize the possibility to make profit is through change. In Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942), Schumpeter introduces the concept of creative destruction as a process where the entrepreneur suits existing knowledge through innovative ways that lead to economic development. The author focuses on the “institutional framework of society, arguing that the increase of rationality undermines entrepreneurship and leads to the stagnation of capitalism” (Landström, Harirch and Aström, 2012). For Schumpeter (1942), the force that sets and keeps the capitalist engine running “comes from new products for consumers, new methods of production and transport, new markets and new forms of industrial organisation that the capitalist enterprises create” (Schumpeter, 1942).

While the work of Schumpeter (1942) is aimed to explain the evolution of the capitalist system, by using the creative destruction to enhance the economic balance, Kirzner (1973) believes that the entrepreneur process brings the economy in a state of balance. His work follows the Austrian heritage of Schumpeter that has been prevalent for many years in entrepreneurship research and exposes the importance of the identification and dealing with opportunities in an unbalanced market. The Kirzner’s entrepreneur leads the market to a new equilibrium, to seek and to coordinate those resources more effectively (Landström, Harirch and Aström, 2012).

Kirzner (1973), entitled “Competition and Entrepreneurship”, mentions that the entrepreneur “is a decision maker, whose role emerges from his alertness to unnoticed opportunities” (Kirzner, 1973). It discusses the concept of alertness, stating that “it is this entrepreneurial component that is responsible for the understanding of active and creative human action, rather than any automatic and mechanical decision process” (Kirzner, 1973). The entrepreneur just needs to detect the opportunities before the others in its early stages. Such attention to the opportunities is what distinguishes the entrepreneur from other market players.

The work of Shane and Venkataraman (2000), entitled “Entrepreneurship as a field of research”, brings a new definition of the field of entrepreneurship. From the authors, it “involves the study of the sources, the process of the discovery, the exploration of the opportunity and the profile of individuals that discover, evaluate and exploit them” (Shane and Venkataraman, 2000). Shane and Venkataraman (2000) ensure that entrepreneurship cannot exist without opportunities and consider the opportunity as an event where goods and services, raw materials and organizational methods can be introduced and sold at a higher value than its cost.

Mark Casson, in his book entitled “Entrepreneurship: An economic theory”, argues that the entire structure of the theory that he developed is based on the premise that the entrepreneur is an individual who specializes in making decisions involving judgment on the coordination of scarce resources. “The entrepreneur is someone, a person. It is not a team, a committee or an organisation” (Casson, 1982). The concept of Casson (1982) relies on the fact that the entrepreneur is an agent of change that not only focuses on the perpetuation of the existing allocation of resources, but in its improvement.

Granovetter (1985) introduces a link between the economic dimension and the social reality. In his work entitled, Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. The author refers to one of the classic questions of social theory: About how behaviour and institutions are affected by social relations. The author criticizes both the super and sub socialization of human action contained in the Classical and Neo-Classical economic theories utilitarian view.

Granovetter (1985) argues that in a modern industrial society, most economic actions are rooted in social relationship structures. The concept of “embeddedness” highlights “the role of concrete personal relations and structures (networks) to generate trust and prevent an illegal conduct” (Granovetter, 1985). According to the author, there is a very high degree of constriction between the organisations, the individuals and their social relations. So, for him, a productive analysis of human action is required to avoid the atomization of social concepts. The approach of “embeddedness” of Granovetter (1985) provides an analysis of the influence of social structure on market behaviour, showing how business relationships are involved with social relationships and networks. Thus, social relations play a disruptive role of change in a market process.

Such brief reflection on the theory foundations of entrepreneurship enhances two specific trends: The economic and the social perspectives of entrepreneurship. They both constitute the key elements of the study of the entrepreneurs of the region of Caxias do Sul, Brazil.

Entrepreneurial Action, Socio-Economic Conditions and Economic Development of the Region of Caxias do Sul (1950-1970)

The industrial manufacturing concentrated activities in Caxias do Sul started in the 1930s when the elected President of Brazil, Getúlio Vargas, adopted a model of import substitution, modifying the agro-export model that had continued in Brazil for almost 430 years. Its expansion came through the participation in the region’s economy in the World War II period, where the metallurgical, the food and textile industries occupied the national market and contributed to the various demands that were due because of the world conflict. This period represented an increase in industrial capacity that, in the 1950s, demonstrated a steadiness in the growth of the economic model.

The industrial manufacturing concentrated activities in Caxias do Sul started in the 1930s when the elected President of Brazil, Getúlio Vargas, adopted a model of import substitution, modifying the agro-export model that had continued in Brazil for almost 430 years. Its expansion came through the participation in the region’s economy in the World War II period, where the metallurgical, the food and textile industries occupied the national market and contributed to the various demands that were due because of the world conflict. This period represented an increase in industrial capacity that, in the 1950s, demonstrated a steadiness in the growth of the economic model.

In the 1950's, the current established economic model focused on the replacement of imports. The introduction of this model, both by the Vargas and the Juscelino Kubitschek governments, had encouraged local companies to seek alternatives strategies to grow in the segments of the markets that were newly opened due to such change. The country was entering in an era of modernization through a diversified and rapid industrialization; which provoked a growth in the domestic industry of the region of Caxias do Sul, (Herédia, 2007).

During the decades of 1960 and 1970, a model of “Associate Dependent” was established in the country by the military government in place, where foreign capital started to interfere in the economic development schemes. The newly government was seeking an “economic policy seeking to correct internal distortions and was intended to restore the credibility of Brazil abroad and to regain the confidence of foreign investors” (Brum, 2003).

The local entrepreneurs of Caxias do Sul incorporated the spirit of fast modernization of such economic development model, which allowed them to develop new businesses, to expand healthy businesses and to adjust them with the creation of new markets in the national industrial sector. Brum (2003) points out that the “Juscelino Kubitschek government” intended to put Brazil in history as one of the most advanced capitalist nations, through the strength of the national company network, especially by industrial expansion and through job creation.

The economic policy of President Kubitschek was decisive for regional development. Its new Target Program (Brum, 2003) was established to help the major industries of Brazil, which included the metal-mechanical industry and the motor vehicle industry. The installation of the automotive program in Brazil favoured the growth of the manufacturing industry that was already expanding in Caxias do Sul.

From 1955, the Brazilian industrial development was oriented toward the production of capital and semi-durable goods. This meant that the country would enter in a new phase of the import substitution process. Such moment would allow the Caxias do Sul industrial network to reach new technological standards and market that were growing in the country. The official economic model was enhancing “The growth of the productive capacity of those sectors came forward to respond to the existing domestic demand for those goods. (Pesavento, 1985).

This new pattern of the Brazilian economy was then generating business opportunities in the national market and directly contributing to the economic development of the region. Consequently, the Caxias do Sul entrepreneurs directed their actions to the discovery and the exploitation of opportunities that were formed within the new industrial markets that were brought up.

The vision of the local entrepreneurs in a regional development perspective appears through a series of actions that fit the model with peculiar characteristics that had been decided previously, which characterizes the action of these entrepreneurs (Dorion et al, 2012; Dorion et al, 2015). In the early 1950s, the industrial entrepreneur class was so attentive to issues of national economy that they resolved separating themselves from the common merchants, creating their own industry representation by creating the Manufacturing Industry Centre. Such decision was not intended to oppose the common merchants, but mainly to deal with main industry issues that were at the time being considered as a priority by the federal government.

The creation of an Economic Department by the Manufacturing Industry Centre, which aimed to link the industrial entrepreneurs’ class with the National Regional Development Bank (BRDE) and other funding agencies, can be considered as an action that reflects the vision of the industrial entrepreneurs. The BRDE was created in order to support the economic activities related to the State economic growth; where the entrepreneurs could use this credit program to promote investment in the secondary sector.

One case to be mentioned is the energy transportation and distribution problems with the CEEE Electric Company. The case is based on the concerns of the local industrials about finding practical solutions to the problems related to the industrial operations at their plants and their urgent need to get effective responses. The Manufacturing Industry Centre decided to request to the State Electric Company (CEEE) to study the possibility of installing public transformers in some specific and defined locations, in collaboration with the concerned entrepreneurs, in order to provide the energy needed for the progress of productive activities. After intense pressure from the entrepreneurs and the Industry Manufacturing Centre, the power supply problem needed for industrial production was resolved in 1966, with the inauguration of Network Electric Company Scharlau-Caxias-Farroupilha.

The last directorate of the Manufacturing Industry Centre was led by Mr. Paulo Pedro Bellini, from the automotive sector, which stood for the growth of the industries of Caxias do Sul, “Especially through his decision to unite both representation entities to strengthen their representation” (Herédia and Machado, 2001). The Industry Manufacturing Centre and the Commercial and Industrial Association merged to strengthen their representation and be more representative for the entire business community. In October 1973, the Chamber of Industry and Commerce of Caxias do Sul (CIC) was finally established.

Method

The objective of this study was to analyse the actions of the entrepreneurs of the industry of Caxias do Sul that contributed to the economic and social development of the region during the 1950-1970 periods. First, a theoretical research on entrepreneurship was realized, taking into account the economic and social dimensions of Landström, Harirch and Aström (2012), which link and classify the key academic studies in entrepreneurship. At this stage and based on the studies of Pesavento (1985), Herédia and Machado (2001), Brum (2003) and Herédia (2007), a theoretical research on the socio-economic conditions and the entrepreneurial activities that contributed to the economic and social development of the northeast region of Rio Grande do Sul (1950-1970) was also carried out. In a second step, a field survey was conducted, in the form of interviews, aiming to verify the position of the social partners on the proposed topic. Finally, the analysis of interviews was realized in order to identify the actions that the entrepreneurs took in view of their business reality and as agents of local development.

The period chosen for the study is significant for its economic and social importance in the history of Caxias do Sul and the Northeast of Rio Grande do Sul. It was in that period that the industrial entrepreneurs of Caxias do Sul were able to absorb the proposed accelerated modernization plan of both the Juscelino Kubitschek government and the military regimes, which made possible to stimulate the industry and provide economic and social development.

Considering the exploratory nature of the study and recognizing the indispensability of methodological rigor in the implementation of academic research, the questions that guided this study were strictly qualitative. Regarding the studies of qualitative nature, Denzin and Lincoln (2008) consider that a qualitative research is an inquisition field itself. It cuts across disciplines, fields of study and subjects. In this case, a complex family of perspectives, interconnected concepts and assumptions surrounded the qualitative research.

The data collection was conducted through guided and recorded interviews with local entrepreneurs of the industry of Caxias do Sul. The guided interview allows the interviewer to use a guide of issues to be explored during the course of the interview (Denzin and Lincoln, 2008).

Sampling was intentional and the respondents were selected complying with the established criteria for being outstanding entrepreneurs from the industry of Caxias do Sul and have contributed for their individual and collective actions in the economic and social development of the region. The industrial entrepreneurs of Caxias do Sul who participated in the interviews are listed in Table 1 below. The participants are identified with a number, their age, the industry sector to which they are bound and their current activity.

| Table 1: Entrepreneurs Interviewees | |||

| Interviewed | Age | Industry Sector | Current Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interviewed 1 | 87 | Metal-mechanic | Industrial |

| Interviewed 2 | 87 | Metal-mechanic | Industrial |

| Interviewed 3 | 84 | Metal-mechanic | Industrial |

| Interviewed 4 | 74 | Metal-mechanic | Former president Caxias do Sul Manufacturing Industrial Centre |

| Interviewed 5 | 72 | Wood | Wood Employer’s Union presidente |

| Interviewed 6 | 73 | Metal-mechanic | Industrial |

| Interviewed 7 | 74 | Metal-mechanic | Industrial |

| Interviewed 8 | 67 | Metal-mechanic | Industrial |

| Interviewed 9 | 76 | Metal-mechanic | Former president Caxias do Sul Metallurgy and Mechanics Employer’s Union |

| Interviewed 10 | 78 | Metal-mechanic | Former vice-president Caxias do Sul Chamber of Industry and Commerce |

| Interviewed 11 | deceased | Metal-mechanic | Former president Caxias do Sul Manufacturing Industrial Centre |

Finally, the analysis of the interview transcripts, using the Miles and Huberman (1994) conception qualitative data analysis, provided a thorough exploration of narratives that serve to understand the perceptions of the discursive messages and to enrich the meaning of the constructs. The use of this method helped to consolidate the categories of analysis in the research corpus and to understand the dynamics of the existing categories. Their analysis explore the convergent content present in the entrepreneur’s narratives about their actions, in order to answer the guiding questions provided in the study and to achieve the objectives proposed by the research.

Discussion

The results explore the corresponding contents of the interviews with the entrepreneurs, through the categories of analysis arising from the literature, whose concepts have emerged analogously in the narratives of the interviewees. The Economic dimension of entrepreneurship, based on Landström, Harirch and Aström (2012) and Shane (2000), studies the main category “new market creation”. This dimension also includes both sub-categories “opportunity”, based on Kirzner (1973 & 1997) Shane and Ventakaraman (2000) and “innovation” based on Schumpeter (1934 & 1942). The Social Dimension of entrepreneurship, based on Granovetter (1985), studies the “social relationship structure” category that presented similar contents in the narrative of the respondents. Noteworthy the discussion will not include the “risk calculation” category (Knight, 1921) and the “resources coordination” category (Casson, 1982), which emerges from the literature but were not encountered in the content analysis of the narratives of the respondents.

New Market Creation

By using the concepts of Landström, Harirch and Aström (2012); Moroz and Hindle (2011), it highlights the importance of the “entrepreneurial role in creating new markets,” since the analogue content of that category shows an evidence on the “absorption” by those entrepreneurs of the rapid process of modernization from the implementation of the economic development model during that period. Also, the narratives show the evidence of a relation between such adaptation to the creation of new markets in the national industrial sector and the development of new businesses and their expansion, as suggested by Herédia (2007). This process of past development in the region is expressed in the following narrative:

1. Regional development coincided with the federal policy on import restriction, which sought, in fact, to develop the country's range of self-sufficient activities, (Interviewee 7, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

2. For us and for the country, the time of Juscelino, in the 50s, was very important as the chassis for buses began to be manufactured in series, which was until then built as a collapsible vehicle. So I think the development in the 1950’s introduced the automotive program in Brazil, starting with Mercedes. So we started to have then someone that made the appropriate chassis for our bus main body (Interviewee 2, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

Taking into account the narrative presented by the entrepreneurs, it is obvious that the economic development of the region was caused by their actions in creating new markets. From the perception of local industry leaders, the economic policy implemented by the federal government constituted a key factor for regional economic development, because the target program of the juscelino kubitschek government provoked and gave focus to the national-based industry, more specifically with the motorized vehicles industry, which benefited the Caxias do Sul industry. Those industrial actors sought alternatives to grow in the new segments that were opened in the 1950’s, from the import substitution model of JK and were able to interact with the economic demands of the military regime, seeking the opportunities to grow in the newly expanded markets during the decade 1960-1970.

The sub-category “opportunity” is sustained in the present research. Shane (2000) ensures that entrepreneurship cannot exist without opportunities and the opportunity is understood as an event in which goods, services, raw materials and organizational methods can be inserted in profitable markets. Shane and Venkataraman (2000) conceive that entrepreneurship involves resources and discovery processes opportunities and individuals who exploit those opportunities. Kirzner (1973 & 1997) understands the entrepreneur as a decision maker, whose role emerges from his alertness to the unnoticed opportunities.

The sub-category “opportunity” is represented in the testimony of the respondents who took advantage from the opportunities created by the economic model of the federal government new policies and, according to Pesavento (1985), triggered a new pattern of accumulation as a result of a focused and deliberate reversal of the production goods sector and durable consumer goods. Such posture supports the argument that the country needed to develop new technical and industrial standards.

This historical context is expressed in the narrative of Interviewee 1, as shown below:

1. When we started our factory in 1954, we started because we had an opportunity to do something. We had no parts and, therefore, we did them. We started doing any engine part, like pistons, rings, valves, cylinder heads, crankshafts and blocks to and controls, which were developed afterwards. (Interviewee 1, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

The statement of Shane and Venkataraman (2000) that entrepreneurship involves “resources” and “opportunities discovery processes” can be observed in the narrative of Interviewed 8, which states: You must try to see where it is an opportunity for you (sic) try something different. (Interviewee 8, industrial meta-mechanical sector). Also the view of Kirzner (1973), which sees the entrepreneur as a decision maker and whose behaviour is defined by his attention to opportunities, is explicit in the narrative of Interviewed 7. In that case, the respondent refers to the deceased father's behaviour, who founded several renowned enterprises and contributed to their actions for the development of the region:

1. He was a worried man. He was always looking for a new "toy". He liked mechanics. He did not comply with his duties. He was a farmer, a truck driver, he founded the Auto Mechanics with a partner and then he put up the “House of tires”. He even invented he wanted to manufacture wheels, after the end of the war. When he saw the opportunity, he went to Italy to seek knowledge and when he saw that to manufacture them an awful investment was needed, he changed his mind and found the brake linings, which was what made it grow and, when it consolidated itself, he began to look for other things. (Interviewee 7, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

As a result of the implementation of the government's import substitution model, in a first moment, the narratives on the actions of the entrepreneurs of Caxias do Sul industry in the period between 1950-1970 allow affirming that they took advantage of the opportunities created by the new national markets. After 1964, such positioning lasted with their actions coped with the associated dependent model of the military regime government. The testimony of the respondents asserted that many entrepreneurs in the industrial sector of Caxias do Sul developed their entrepreneurial behaviour by being attentive to the discovery process and exploitation of opportunities created by the new markets in that period.

Innovation

The sub-category “innovation” as initially introduced by Schumpeter (1934 & 1942), understands that the economic development as a structural process of change is driven by innovation and is characterized by the implementation of new combinations. It may include the introduction of a new product or a new product quality, the establishment of a new method of production, the opening of a new market, the conquest of a new source of supply of materials or semi-finished products or the management of a new organisation. Through this theory, the “innovation” category is identified in the narratives of the interviewees, who witnessed that they were able to innovate in the markets that have been created in the governments during the period 1950-1970. The way to innovate for those industrials reflects the thoughts on innovation of Schumpeter (1934 & 1942) that the project is the realization of new combinations and that the entrepreneur is someone who takes care of the development of those new organisations.

The view of Schumpeter (1934), which is based on the creation of new combinations, as it is highlighted in the narratives of the interviewees, associates the “ethnic factor” to such action behaviour, as can be perceived from the case of Interviewee 6:

1. The “Caxiense” is an entrepreneur today because he is from Italy, from where they were at a very submissive moment in history. So much that they decided to come to Brazil because they did not feel well, felt very sacrificed and came here with the goal of creating a new world, to create new things. This left them with the spirit and the will to win. This desire to win created our “Caxiense”, with the mentality to undertake (Interviewee 6, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

Furthermore, the concept of Schumpeter (1934 & 1942) on innovation refers to the implementation of new combinations that include the introduction of a new product or a new product quality. It is portrayed in the thoughts of the interviewed entrepreneurs, such as the Interviewee 5, which recalls:

1. Our company, in reference to innovation, created a manufacturing housing industry, which did not exist in the country. It broke new ground because, until then, the houses were traditionally built with a hammer, sawing with hand saw, putting piece by piece, etc., the delay of the construction was very important and we innovated by manufacturing panels that were already mounted and were simply assembled, for a 80-100 m² house, in a matter of a week and was delivered promptly and completed to the customer's. That was our creation. Our architects, our engineers came up with the house and then we started building them (Interviewee 5, president of the Caxias do Sul Wood Union).

The international competition in the Brazilian domestic market that happened in the late 1960s, especially in the automotive parts sector, reinforcing the tradition of innovation of some industrial establishments of the region. They implemented their actions to consolidate their trade relations in international markets, as an output to internal competition, which was increasing considerably in Brazil in that period. The narratives show such concepts of Schumpeter (1934 & 1942), where the action of the entrepreneur is focused on the opening of a new market or the creation of new organisations to attend such market. The innovative efforts of the “Caxiense entrepreneurs” to consolidate their trade relations in the international markets as a solution to internal competition is evident in the testimonies of Respondent 2, which states that, You cannot sit idly at home. You have to travel the world to see new things, because if not, you do not innovate (Interviewee 2, Industrial metal-mechanic sector). This effort is evident also in the narrative of Respondent 4:

1. In 1964, I made a group and we did the first Brazilian consortium of export nobody was exporting here. We hired a trainer from the Department of External Affairs of Brazil, the Itamarati, who came to work with us in Caxias do Sul, very well paid, with twenty or so companies that were participating in the consortium. The companies, all driven by this professional, began to make their brochures in several languages; they began to organize and started to export. First, I went to New York on a trip, with the help of the Brazilian Consulate, with the Bank of Brazil, to open market in the United States. We carried products in the suitcase and then participated in a fair in Dallas, Texas. (Interviewee 4, former president of the Manufacturing Industry Center of Caxias do Sul).

Therefore, based on the economic context of the 1950s and 1970s and in the view of some respondents, it is clear that the actions of the industrial entrepreneurs of Caxias do Sul show an innovative way in taking business decisions. In reference to their position, the idea of efforts to induce and change their way of doing business is a demonstration of market innovation that affected in the economic growth of the region. In addition, it is important to point out the existence of an entrepreneurial mind-set that is rooted to a particular ethnic origin, the Italian colonization and their sole idea to create something new. The effort by the “Caxiense” entrepreneurs to develop new markets, to act in an innovative way to create new products happened at the same moment or so, with the specific clue to establish operational solutions together with other entities in the market.

Social Relationship Structure

The “social relationship structure” category of Granovetter (1985) argues that in a modern industrial society, economic actions are rooted in social structures of relationship. They “embededness” the role of concrete personal relations and structures (networks) to generate trust and prevent the development of any illegal conduct. The idea of “social relationship structure” of Granovetter (1985) can be contextualized in a specific business relationship between public banks and the telephone or electric companies that look forward to implement new infrastructures. In this context, the Manufacturing Industry Center played a relevant role, representing the voice of the interests of the industrial sector of Caxias do Sul, with the creation of an Economic Department in the Manufacturing Industry Center, which aimed to strengthen the relationship of the industrial entrepreneurs with the Regional Development Bank (BRDE) actors.

During this period, the industry benefited of some credit programs from the BRDE for the construction of plants in the manufacturing sector, including long-term financing and limited indexation. The narrative of Interviewee 2 points it out, as follow: BRDE was very good for us in the 1960s onwards. It was at the time where several pavilions were built and finally did at that time, the plant at the Plateau neighbourhood (Interviewee 2, industrial metal mechanic sector). The same idea is shared by Interviewee 3, who recalled: In 1960, when the revolution came, the military held inflation, implemented some works that then no one else did and we thanks God also it went ahead, making money, then we made a new factory with BRDE because of an eight to nine years funding scheme (Interviewee 3, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

The narrative speech of Interviewee 11, who has been president of the Manufacturing Industry Centre of Caxias do Sul in 1960, explains the existence of a relationship mechanism that is adopted by the industrial “Caxienses” with the banks linked to the government:

1. The Manufacturing Industry Centre always participated in the entrepreneur’s claims with the federal government. We were looking for credits from BRDE, because at that time all companies were handcraft based and needed credits to grow. So we claimed the BRDE, with the federal government for more lines of credit from the Bank of Brazil and rediscounted some given guarantees. It was a tremendous fight, even in the time if the government was revolutionary in his way of doing business. We had to fight quietly (Interviewee 11, former president of the Manufacturing Industry Centre of Caxias do Sul).

In addition to the attention given to the relationship with public banks, the industry entrepreneurs also teamed up around issues related to insufficient telephone and electricity infrastructures in the city. Respondent 4, which also was president of the Manufacturing Industry Centre in the 1960s, draws the scenario of structural shortage that involved the “Caxienses” industries, as shown: In the Industry Centre Manufacturing network, it was known that there was not the quantity of electricity required to grow. Companies wanted to establish, expand and had no energy. This situation of lack of infrastructure is presented by respondent 2, which recounts his personal experience:

1. We had a very acute problem in relation to electricity. After we had no good telephone system; contacts with suppliers and vendors were very complicated. The infrastructure at that time was very precarious and those situations were inherent difficulties of the industrial sectors in general. At one time, we set up a radio station in São Paulo; a frequency that worked together with the Matarazzo company and we used it to contact suppliers (Interviewee 2, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

The good business relationship established by the industrials of Caxias do Sul with the Government helped to resolve the structural problem of electricity in 1966. It allowed the connection of Caxias do Sul with Scharlau, via Farrouplinha and an additional transmission capacity of 14,000 kW and resolved a problem that had been forming for a long time, creating a bottleneck in the growth of the industrial park of Caxias do Sul (Herédia & Machado, 2001, p. 85). The Interviewed 4 recalls the events leading up to the problem solution, exposing:

1. I was able, as president, to have the State government to construct a powerline. And before that, that a thermoelectric plant in Kaiser neighborhood was built. This plant was the result of several trips to Porto Alegre, only this thermal powerplant was simply absorbed by the existing pent-up demand. The moment it began, it met the demand, but there was way out to expand it anymore. So we also got the State government to build a transmission line from Scharlau to Farroupilha and Caxias do Sul. But the construction would not come out. The government said yes, but we would go back, because the promises were great. (Interviewee 4, former president of the Manufacturing Industry Centre of Caxias do Sul).

From the claims of the Manufacturing Industry Centre the Caxias do Sul industrial network could be classified as the “Metal-mechanical area of the State of Rio Grande do Sul.” (Héredia & Machado, 2001). From the author, the Government of Mr. Sinval Guazzelli, this claim was publicly taken together with the Department of Trade and Industry and the Coordination and Planning. In February 1979, the Governor of the State recognized the industrial potential installed in the city and signed the decree that defined the metal-mechanic complex in Caxias do Sul. The Interviewee 3, who chaired the Chamber of Industry and Commerce of Caxias do Sul in 1975, speaks of the importance of the dialogue held by the institution on behalf of the “Caxiense” business community:

1. The Chamber of Industry and Commerce was formed in such a manner that it became one of the best Chambers of the interior of Brazil. It always acted strong, then any complaints made from any company, the Chamber of Industry and Commerce would resolve them. Because to know if a business owner will complain is one thing, but when a Chamber of Commerce do, it has another weight. This has always been so in the Chamber (Interviewee 3, industrial metal-mechanic sector).

It can be argued that for the period between 1950 and 1970, the industry entrepreneurs organized their business sector around associations, which were able to mediate their relationship with the government. They joined around priority issues for them, such as those related to the relationship with public banks and those related to insufficient telephony infrastructure and electricity. This effort resulted in deepening business relationship with the banks belonging to the government and solved the most pressing problems of the city infrastructure, such as electricity alimentation. At that time, the industry entrepreneurs knew how to develop a skilled and firm behaviour with respect to issues involving their relationship with the government and interfered in the process.

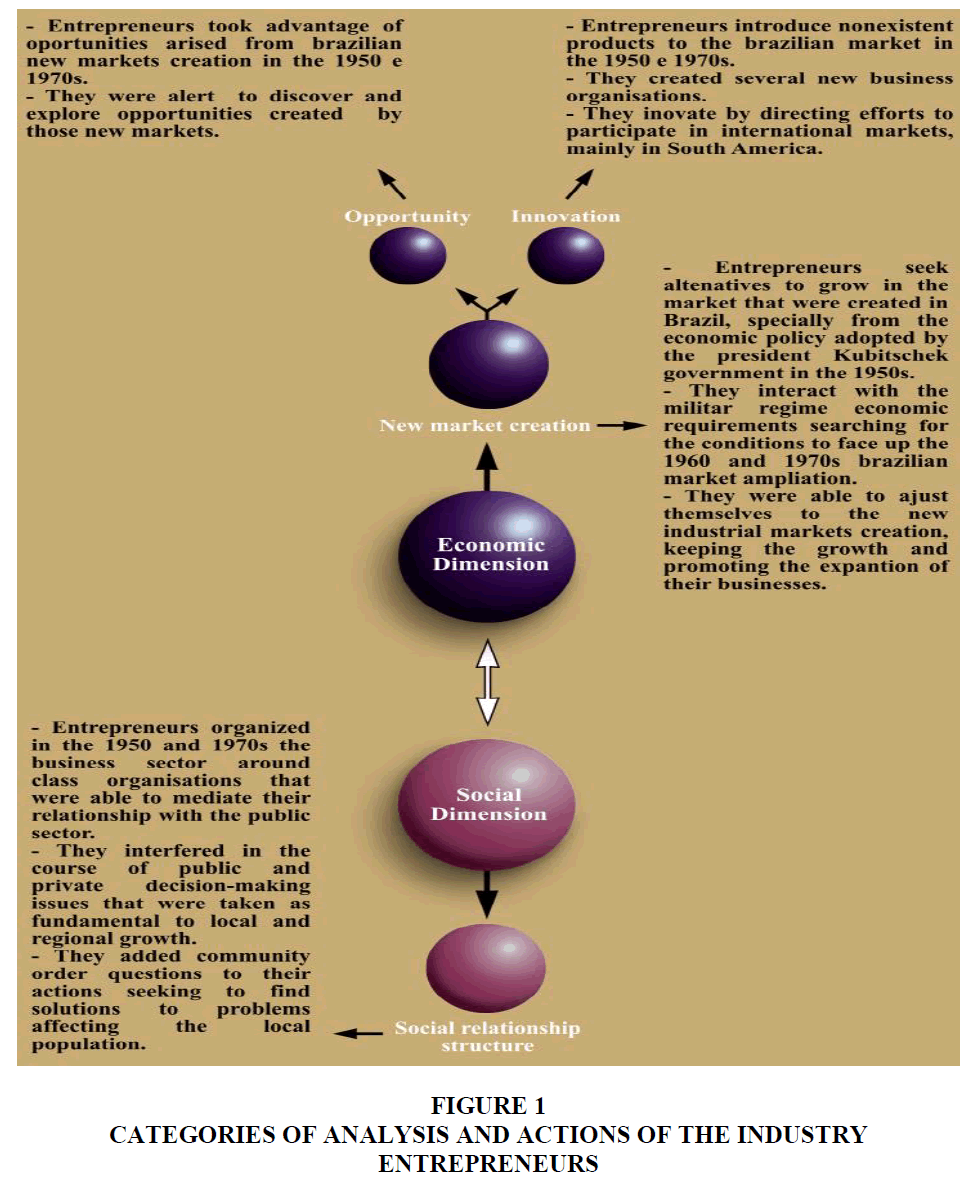

To finalize the analysis and discussion, Figure 1 shows the two dimensions of entrepreneurship considered as the categories adopted for performing the analysis as well as a summary of the actions of the industry entrepreneurs.

Conclusion

This study identifies the socio-economic conditions that affect the economic formation of the region of Caxias do Sul through entrepreneurial activities. It verifies the existence of the relation between the actions of the entrepreneurs with the conditions of regional economic development and it describes the collective and individual actions of the entrepreneurs toward the construction of economic development regional.

The results show the evidence that the establishment of an economic model of import substitution by the Government of Juscelino Kubitschek that encouraged the companies of the region to seek alternatives to grow in the segments of the markets that were opened from that event. In that period of history, the country has decided to enter in the era of modernization through a hasty and rapid industrialization. This period was marked by a change in the economic model that has imposed the implementation of agile and efficient organisations, dedicated mainly to the interests of the secondary sector. The growth of the domestic industry favoured the economy of Caxias do Sul and generated one of the main industrial pole in the country, changing and boosting the profile of the local industry and the State's economy.

This economic environment stimulated new actions by the Caxias do Sul industrial entrepreneurs in order to adhere to the new market demands; maintained an economic growth and ensured the expansion of their industries. In this period of economic history, the industrialists showed aptitude to interrelate with the new economic conditions, pursuing the conditions to operate in markets that were expanding.

Considering the discourse of the interviewed entrepreneurs, it is possible to sustain that the economic development of the region was caused by the actions of those entrepreneurs in creating new markets. The entrepreneurs believed that the economic policy of the Kubitcheck government, which was directed toward the implementation of a national industry-based productive network, included the automotive industry and favored the “Caxiense” automotive industry to deploy manufacturing transformation activities. Because of this, those entrepreneurs founded the Industry Manufacturing Centre in 1955 that defended the specific interests of the industrials, who brokered the expansion of the city, the state and the country industry.

By analysing the displayed economic context and the manifestation of the local industry entrepreneurs, it is possible to assert that the actions of those entrepreneurs are a demonstration of the strength of the attributes of the individuals facing the opportunities of empowerment and the use of the conditions that promoted the economic development of the region. The statements of the entrepreneurs demonstrate that they were able to take advantage of the opportunities created by the government’s economic development model at a time when the leadership of the industrialization process migrated to the production of durable consumer goods, becoming the sector more dynamic of the Brazilian economy. The testimonies of the respondents ensure also that many entrepreneurs in the industrial sector of Caxias do Sul were able to seek, on purpose, the opportunities created in markets around the industrial sector. They developed an entrepreneurial behaviour to be attentive to discover, evaluate and exploit the opportunities in the market.

In the period between 1950 and 1970, the industry entrepreneurs coalesced around emerging issues, such as those related to the relationship with public banks, to resolve the telephone and electricity infrastructure failures. This commitment enhanced the business relationship deepening with government banks and allowed to solve the immediate problems of municipal infrastructure.

At this time of the history of Caxias do Sul, the industry entrepreneurs were able to improve a skilled and firm behaviour with respect to issues involving their relationship with the government. In addition, they were able to associate and to generate community order questions that sought to find solutions to problems that affected the population of the municipality in general. Furthermore, the actors went beyond business issues and have become economic development agents, since their individual and collective actions were decisive and led to the region’s growth. Therefore, it can be concluded that the entrepreneurial activities in the economic history of the region of Caxias do Sul points out the presence of social relations between the public and private sectors, reflecting the capacity building of relationships needed to create the economic development of the region.

This study sought to fill out the gap regarding the understanding of the historical and economic factors that allowed the city of Caxias do Sul to grow economically and socially. But unlike any other places that had similar initial conditions of establishment, to achieve a different level of economic and social development. Still, the study sought to understand if there is a direct influence between the actions of the local entrepreneurs “into” the socio-economic development process.

The richness of this research relies in the search for links between the actions of entrepreneurs and the economic history of Caxias do Sul, which required a reflection on important issues surrounding the entrepreneurship field of study, such as the creation of new markets, the opportunity and innovation, the social and individual relationships and collective attributes of the “Caxiense” entrepreneurs.

Future studies could attempt to respond to the entrepreneurial activities of the industrial entrepreneurs of Caxias do Sul, in this period of history, by studying the continued presence of cultural values, such as labour, property, savings, associations, family, religion and competition, which stimulated the economic development of the region. It could also try to answer to the same guiding questions used by considering another historical period of the city's industry, such as the Post-Fordism period of the industry, which started in the late 1980s. Most importantly, it could also study any other specific industrial region in the world that presents the same socio-economic profile.

Finally, a limitation of the study refers to the proper limitation of the timeframe, in a historical perspective. Although the historical period of the survey is fundamental to understand the contribution of Caxias do Sul industrial entrepreneurs for the economic and social development of the region, it does not treats the complete historical timeframe, necessary to understand the full extent of the research contribution.

References

- Andersson, M., Braunerhjelm, P., Thulin, P. (2012). Creative destruction and productivity: Entrepreneurship by type, sector and sequence. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy, 1(2), 125-146.

- Brum, A.J. (2003). O desenvolvimento econômico brasileiro (Twenty Third Edition). Petropolis; Ijuí, BR: Vozes e Editora Unijuí.

- Casson, M.C. (2013). Entrepreneurship. International Library of Critical Writings in Economics, 5(13).

- Casson, M.C. (1982). The entrepreneurship: An economic theory. Oxford, UK: Martin Robertson.

- Denzin, N.K. & Lincoln, Y.S. (2008). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Dorion, E.C.H., Severo, E.A., Olea, P.M. & Nodari, C.H. (2012). Brazilian entrepreneurship reality: A trilogy of imitation, invention and innovation. In T. Burger-Helmchen (Org.), Entrepreneurship-creativity and innovative business models. (pp. 81-98) Rijeka, HR: InTech.

- Dorion, E.C.H., Nodari, C.H., Olea, P.M., Ganzer, P.P. & de Mello, C.B.C. (2015). New Perspectives in entrepreneurship education: A brazilian viewpoint. In J.C. Sánchez-Garcia (Org.), Entrepreneurship education and training. (247-260) Rijeka, HR: InTech.

- Gartner, W.B. (1988). Who is an entrepreneur? Is the wrong question. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 13(4), 47-68.

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481-510.

- Herédia, V.B.M. (2007). Memória e identidade: CIC. Caxias do Sul, BR: Belas-Letras.

- Herédia, V.B.M. & Machado, M.A. (2001). Câmara de indústria, comércio e serviços de Caxias do Sul: Cem anos de história. Caxias do Sul, BR: Maneco.

- Frese, M. (2009). The psychological actions and entrepreneurial success: Na action theory approach. In: Baum, J.R., Frese, M., Baron, R.A. (Eds). The Psychology of Entrepreneurship. Mahwah, New Jersey, Lawrence Eribaum Associations.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. (2015). Cadastro Central de Empresas 2013. Rio de Janeiro, BR: IBGE.

- Kirzner, I.M. (1997). Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: An Austrian approach. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 60-85.

- Kirzner, I.M. (1973). Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago, IL: University of Press.

- Knight, F.H. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit. Boston, MA: Hart, Schaffner; Marx; Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Landström, H., Harirch, G. & Aström, F. (2012). Entrepreneurship: Exploring the knowledge base. Research Policy, 41, 1154-1181.

- Miles, M.B. & Huberman, A.M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Moroz, P.W. & Hindle, K. (2011). Entrepreneurship as a process: Toward harmonizing multiple perspectives. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 781-818.

- Pesavento, S.J. (1985). História da indústria sul-riograndense. Guaíba, BR: Riocell.

- Rocha, V.C. (2012). The entrepreneur in economic theory: From an invisible man toward a new research field. FEP Working papers, 459, May 2012.

- Schumpeter, J.A. (1942). Capitalism, socialism and democracy. Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York, NY.

- Schumpeter, J.A. (1934). The theory of economic development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization Science, 11(4), 448-449.

- Shane, S. & Venkataraman, S. (2000). Entrepreneurship as a ?eld of research. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217-226.

- Sindicato das Indústrias Metalúrgicas, Mecânicas e de Material Elétrico de Caxias do Sul. (2015). Resultados Econômicos das Empresas do SIMECS. Caxias do Sul, BR: SIMECS.

- Thornton, P.H., Soriano, D.R. & Urbano, D. (2011). Socio-cultural factors and entrepreneurial activity: An overview. International Small Business Journal, 29(105), 105-118.

- Watson, T.J. (2012). Entrepreneurship: A suitable case for sociological treatment. Sociology Compass, 6(4), 306-315.