Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 4

Expectations of Estonian Vocational Teacher Students on Entrepreneurship Education

Karmen Trasberg, University of Tartu, Estonia

Citation Information: Trasberg, K. (2021). Expectations of Estonian vocational teacher students on entrepreneurship education. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 24(4).

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to examine the VET teacher students' expectations regarding the content of the entrepreneurship education in teacher training. It draws both on the literature relating to entrepreneurial mind-set and on competence model in order to frame entrepreneurial studies for future teachers. The qualitative research method was used. Data was collected with 16 in-depth interviews with the VET teacher students. Inductive content analysis is used as the method of data analysis. The results of the study showed that the VET teacher students identifying transferable competencies (e.g. creative thinking, teamwork and communication skills, self-management, etc.) as most relevant for them. When planning the content of entrepreneurial studies, knowledge and skills acquired during prior learning and work experience must be taken into account. The results of the study are valuable for designing entrepreneurial studies module and integration of entrepreneurial competence into other subjects.

Keywords

Teacher Education, VET, Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Mind-set.

Introduction

Adaptation and self-management capability, social skills, critical thinking skills, creativity, entrepreneurial attitude and perseverance are important at every level of Estonian education for next fifteen years. Entrepreneurial mindset is one of the basic values of Education Development Plan for 2035 (Estonian Ministry of Education and Research, 2019).

Developing learners’ entrepreneurial mindsets requires learning processes that support active, experiential learning and fosters the development of entrepreneurship competencies. As Venesaar et al., (2018) highlighting, competency based approach allows seeing entrepreneurship education 1) as a discipline (offering separate courses) or 2) as a method (a teaching approach, embedding entrepreneurship education into curricula. At the same time, entrepreneurship education needs to be adapted to different target groups: those who have already set up a business or starting a business and those learners who are not entrepreneurs by themselves but will implement entrepreneurial attitudes of students.

In entrepreneurial education research little attention has been paid to teacher students and there is need both for exploration of how students interpret entrepreneurial education and tools that support them to develop competencies and entrepreneurial mindset. At the same time, the “institutions that develop teachers for vocational education should include the development of entrepreneurial competencies (i.e., entrepreneurial knowledge and creative thinking), and behaviour in their curriculum” (van Dam et al., 2010:970). According to the Eurydice report (2016) one third of European countries do not have any central regulations about entrepreneurship education in initial teacher education. Half of teacher training institutions have autonomy to decide the status of entrepreneurship education in teacher education curricula. There are only three countries in Europe where entrepreneurship education is compulsory topic in initial teacher education - Estonia (for all teachers), Latvia (in primary and general secondary level) and Denmark (in basic education) (Eurydice, 2016).

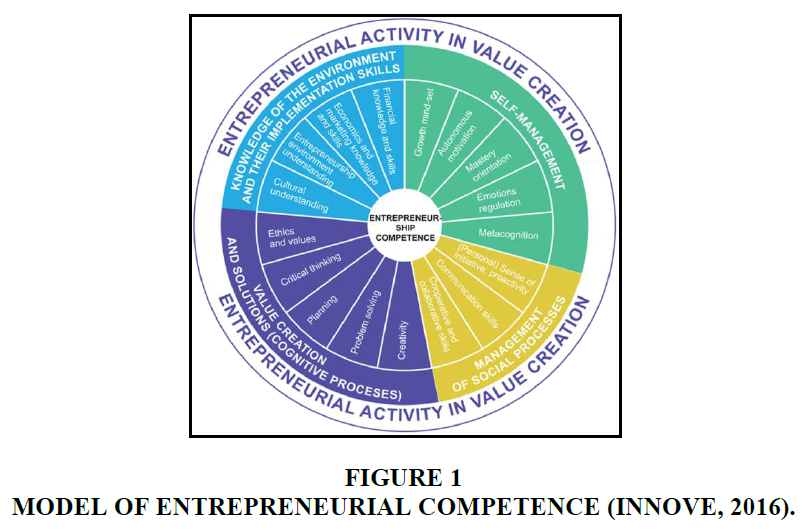

In Estonia the entrepreneurship competence model for teachers was designed in 2016/2017 by the Foundation Innove - an education competence center that coordinated and promoted general and vocational education. In the process of designing the competence model, also assessment tool for measuring the competencies was developed. Four competence areas, presented in the model are: self-management, solving social situations, creative thinking and acting on opportunities (Venesaar et al., 2018). The competence model can be used as a basis for formulating learning outcomes for all educational levels, as well as planning the programmes for entrepreneurship courses (based on established outcomes) and developing pedagogical tools and instructions.

The context of this study is based on the vision and requirements of the University of Tartu, where from 2020 each curriculum must include at least 3 ECTS of entrepreneurship studies. This priority is also emphasized in the Development Plan 2021-25, which states that university is accelerator of smart economy and values the entrepreneurship of its members (Development Plan for University of Tartu, 2020).

The aim of this study is to find out the VET teacher students' expectations regarding the content of the entrepreneurship education. There are three research questions:

1. What are the main characteristics of entrepreneurship competence according to the opinion of VET student teachers;

2. How are entrepreneurial competencies integrated into the curricula of VET teachers?

3. What are VET teacher students' expectations on implementing entrepreneurship education across studies?

First, I will introduce the theoretical background. In the second chapter I am presenting the research design. In third chapter the findings of the study are presented and finally the findings and limitations of the study will be discussed.

Theoretical Background

European Commission identified sense of initiative and entrepreneurship as one of the eight key competences necessary for a knowledge-based society. The goal is to “raise consensus among all stakeholders and to establish a bridge between the worlds of education and work” (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). Entrepreneurial competences, referring to a sense of initiative involving creativity, risk-taking and ability to turn ideas into action, is increasingly seen as a key competence of each individual (European Commission, 2006).

There is awareness that entrepreneurial attitudes can be learned and in turn lead to the widespread development of entrepreneurial mindset and culture (Bacigalupo et al., 2016). This also concerns teachers as promoters of entrepreneurial mindsets and behaviour at all levels of education (Peltonen, 2015). Neck & Greene (2011) stated that entrepreneurship education is about increasing student’s ability to anticipate and respond to societal changes. As Saks & Virnas (2018) are highlighting, entrepreneurial education and student companies programme supports the development of social skills, creativity, innovation and youngsters’ personality traits, enabling them to effectively enter the job market as well as contribute to the society as an active citizen.

In teacher training context, a broad description of entrepreneurship is commonly used, which includes the entrepreneurial mindset and a skill set for entrepreneurs. Competency based approach allows seeing entrepreneurship education as a discipline and as a method and teaching approach, embedding entrepreneurship education into curricula (Venesaar et al., 2018; Blenker et al., 2011; Fayolle, 2013). According to Gibb (2002; 2011) entrepreneurship education is about learning for entrepreneurship, learning about entrepreneurship and learning through entrepreneurship. In order to adapt those concepts for teacher training, learning for entrepreneurship covers, for example, the pedagogical models used by the teacher educators, such a problem based and experiential learning (Seikkula-Leino et al., 2015). Learning about entrepreneurship means that the learner acquires information about the enterprises and business life. Learning through entrepreneurship focus on exploitation of entrepreneurial learning environments like activities in Young Enterprise incubator, start-ups etc.

Cope (2005) recognizes that entrepreneurial learning cannot be characterized by the notions of stability, consistency, or predictability. Rather, this is a dynamic process where learning from experience and “critical learning events” has become a central and unifying theme. There is also issue of teacher supply and competency and how to find “optimum organization design” for delivery of entrepreneurship education (Gibb, 2002).

In Estonia there have been attempts to conceptualize the subcomponents and their relationships of entrepreneurial competence and in this process, a model of entrepreneurship competency have been created that relies on relevant pedagogical, entrepreneurial and psychological knowledge, see Figure 1. According to the model, the entrepreneurship competence consists of four dimensions that divide, in turn, into sub-competencies. These are called self-management (regulating one’s own motivation, ability beliefs, emotion regulation, and metacognition); value-oriented thinking and problem solving (higher-order cognitive processes like planning, problem solving, but also a level of thinking development and value-based and ethical reasoning); solving social situations (social skills, cooperation, initiation) and more domain-specific knowledge about how to realize entrepreneurial ideas (knowledge about business environment, business possibilities and financial literacy).

Earlier studies (Gibb, 2011; Elenurm, 2018) have shown that having entrepreneurial experiences has a positive effect on entrepreneurship education. It will help to ask questions like: is the learner’s priority independent entrepreneurship or intrapreneurship? Is the learner oriented to entrepreneurship in a co-creative team, to individual entrepreneurship or prefers to be self-employed? As well as readiness of the learner to start and/or to develop a real enterprise during the entrepreneurship education programme (Elenurm, 2018). Active participation in simulations, collaboration with entrepreneurs and engagement in student competitions, stimulate student’s creative thinking in terms of using innovative technologies, services, products to energize the programme (van Dam et al., 2010).

One of the challenges identified in the entrepreneurship education, is assessment practice. According to Pittaway et al., (2009), innovative forms of learning (simulations, action- and experiential learning) encourage educators to apply innovative methods of assessment. To understand student’s motivational changes, “integrative” assessment practices could be considered: actual start-ups, venture simulations, poster presentations (Pittaway et al., 2009).

To assess the changes in behaviour and attitudes there is a need for a peer- and self-assessment (Ruskovaara & Pihkala, 2015) recording reflections of learning journey and making competences visible through e-Portfolios or other Digital formats (Korhonen et al., 2019).

Research Design

This study employs a qualitative approach, seeking to understand the personal perspectives of VET teacher students. Data were gathered using semi-structured in-depth interviews. In-depth interview is an effective qualitative method for getting participants to talk about their personal feelings, opinions, and experiences and share how they interpret the topic (Milena et al., 2000).

Interviews were conducted with 16 VET teacher students. These are students who have at least an upper secondary vocational education and are now acquiring a teaching profession in bachelor's studies programme. A purposive sampling technique (Saunders et al., 2016) was used. The participating teacher students had different educational backgrounds, half of them (8 persons) had previous entrepreneurial experience, half did not. For an overview of participants’ educational and entrepreneurial background see Table 1. The average age of participating students was 39. The interviews were of 55-60 min duration and conducted in October and November 2019.

| Table 1 Informants’ Background Information | |||

| Educational Background | General Upper Secondary | Vocational Studies | Bachelor Degree |

| No entrepreneurial experience | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| Entrepreneurial experience | 1 | 6 | 1 |

The aim of the interview was to identify the VET student teachers opinions, beliefs and expectations regarding the content of the entrepreneurship education at the university. Teacher students were informed about goal and content of the interview questions and were asked to give permission for anonymous use of the data in the research. In order to establish the credibility, the following procedures were followed: the interview questions were piloted with two VET teachers who did not belong to the research group. Creswell & Miller (2000) emphasizes the importance of checking how accurately participants' realities have been represented in the final account. This is reason why all participants were involved in assessing whether the interpretations accurately represent them.

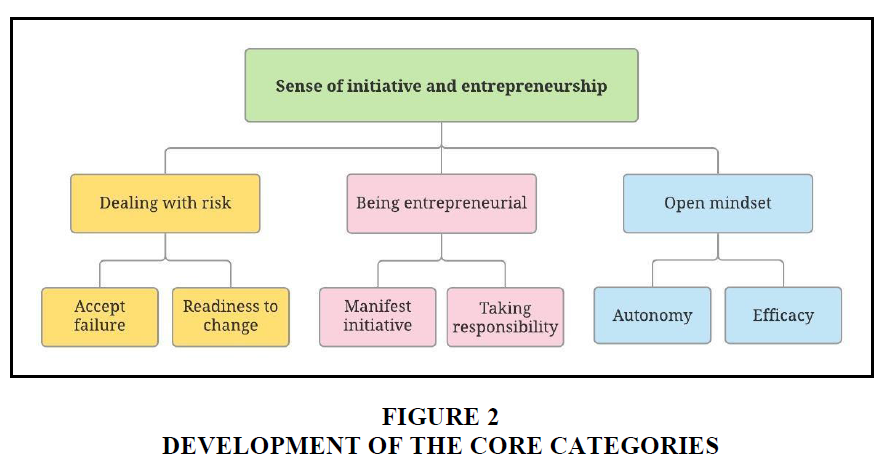

Data analysis: After collecting the data, all 16 interviews were transcribed and inductive content analysis was used as the method of data analysis. First, transcripts were initially analyzed using “open coding” that inductively abstracts patterns and themes in the data related to the both research questions. Reliability of this analysis was checked by discussing the code scheme with another colleague with knowledge of the topic. During the second stage of analysis thematic text coding was done, using the QCAmap software (QCAmap, 2020). The codes were clustered into categories, which were then reorganized into four core categories and then condensed further into the study’s key themes (Saldana, 2016). The example of development of the core categories can be seen in Figure 2.

Results

The answers to the first research question indicated that the fundamental competences for VET student teachers are: self-management, developing sense of initiative and entrepreneurship, and creative thinking. As one of respondents summarizes:

Creativity, playfulness and an entrepreneurial attitude in every activity are especially important for the VET teacher.

Students were also highlighting competences connected to management of social processes, like communication and collaborative learning and proactivity:

I think that for me most important aspect is cooperation and collaborative learning - the emotions, dynamics and challenges like time management and division of work within the team have clear impact on my studies and my future career.

The knowledge necessary for entrepreneurial action was emphasized by VET student teachers with previous experience as an entrepreneur. For them important competence areas are marketing and financial literacy skills.

As a practicing entrepreneur, for me particularly vital knowledge is how to inspire and communicate a vision in marketing.

Risk appetite and the ability to cope with awkward and crisis situations are considered to be very important competencies for all respondents.

VET teacher students identified also set of transferable competencies: creative thinking, problem-solving, teamwork and communication skills, planning and sustainable and ethical acting as very relevant for their teaching career. Important attitudes for the new generation of teachers were emphasized; for example, doing their work in meaningful way, have mission and faith in their ability to change the things in vocational education and training.

Thus, it can be said that VET teacher students value all the competencies presented in the competence model in one way or another. Teachers with entrepreneurial experience also consider understanding the business environment and financial literacy important. Inexperienced teachers emphasize in particular the competencies that relate to communication, collaborative learning, self-management, developing sense of initiative and entrepreneurship and creative thinking.

The second research question was about, how entrepreneurial competencies are integrated into the curricula of VET teachers. Here, VET teachers emphasize in particular the importance of internships and mention specific subjects that support entrepreneurial competences in an integrated way with other competencies. Through continuous pedagogical traineeship, negotiation and planning skills are developed, as well as communication skills. Many entrepreneurial competencies and attitudes are related to the writing and public defense of final thesis, such as joint planning, peer assessment, argumentation and presentation skills. Also self-assessment is widely used - students set a goal they want to achieve and self-assess to extent to which they have met the goal.

Entrepreneurial initiatives are practiced through involvement in curriculum development process by giving a feedback on the whole learning process and planning the necessary changes.

Students explain how they plan individual learning pathways based on professional standard of VET teacher:

For me the most important tool is my professional development portfolio in order to reflect on my competences and present the personal growth as a teacher.

Interviewees emphasized that self-assessment and analyze of the different components of the entrepreneurship competence in the light of personal development is the main channel to integrate entrepreneurial competencies into the curricula of VET teachers. Creating of e-Portfolios was described as a most effective study method to reflect about learning process, to promote personal growth and acquiring entrepreneurial competences of teacher.

The third research question examined the teacher students' expectations on implementing entrepreneurship education across studies. In this regard, VET teacher students expect that combination of objectives, learning outcomes, content and teaching methods are more adapted to the specific audiences. This applies in particular to those courses which are given in a large lecture hall to all students together:

There is still a big difference between teaching entrepreneurial competencies to a kindergarten teacher or to a vocational teacher, but we all are learning together in a large lecture hall.

The learning environment could encourage risk-taking; risk-management and learning form failing. Learners see the learning environment sometimes as too secure, with no room for making mistakes and learning from them. Opportunity to take more initiative and responsibility is coming from working on the individual or team-based projects and it should be more essential and prioritized in the curriculum:

I am wondering, how to make learning by doing an integral part of a university degree…

Learners with entrepreneurial experience are expecting more authentic knowledge of working life and networking with business. Real visits to different companies and experiential learning would allow them to enhance cooperation and develop their own network. Those students are also ready to share their own experience with fellow learners:

Learner-to-learner experience could be integrated into the curriculum. I would be happy to share my gains and failures as an entrepreneur.

The exchange of firsthand experiences could be integrated into the final seminars of the internship and the subject of didactics.

One of the expectations concerns the adaptation of teaching methods suited for integrating entrepreneurship competence into subject courses. In parallel with their studies, most teacher trainees are teaching a subjects or guide a practice at vocational schools, making them interested how to integrate topic to study programmes:

Team learning methods and team projects could be implemented instead of individual learning.

To sum up, student teachers expect that the content and methods of entrepreneurship education are adapted to the audience, depending on their previous experience and field of studies. VET teacher students are enthusiastic to take initiative and responsibility in making individual and team-based projects and share personal success stories and failures with co-learners.

Discussion

In line with Fayolle (2013) who called for deeper investigation of the most effective combinations of objectives, content and teaching methods for future entrepreneurship education, the paper seeks to examine the VET teacher students' expectations regarding the content and methods of the entrepreneurial studies. It looked at the teacher trainees interpretations of entrepreneurial competence in the frame of competence model (Innove, 2016).

Students are highlighting competencies needed for developing entrepreneurial mindsets, creative and entrepreneurial members of society. The results of the study clearly indicated that the VET teacher students identifying those competences, which are central in management of social processes: sense of initiative and entrepreneurship, communication, cooperative and collaborative skills. Value creation competences (e.g. creative thinking, problem-solving, planning) are also highlighted as very relevant for their teaching career.

There is broad agreement that entrepreneurial education challenges traditional teaching practices (Morselli, 2018). Creative and innovative teaching, student centered experiential pedagogies and learning by doing, focused on practical activities and projects, support learners entrepreneurial skills and attitudes (Penaluna & Penaluna, 2015; Nabi et al., 2017; Mueller & Anderson, 2014). The results indicated that student teachers are expecting more authentic experiences of working life and networking with business. This finding confirms Seikkula-Leino et al. (2015) conclusions that in teacher training greater use could be made of co-operative operations, on-the-job learning and methods such as business incubator etc.

Students with entrepreneurial experience highlighted competences connected to knowledge about entrepreneurial environment and acting on opportunities. This is competence area necessary and essential for entrepreneurial action and becoming an entrepreneur (Venesaar et al., 2018).

The study revealed the importance of reflection and self-assessment in process of acquiring entrepreneurial competences of teacher. Creating of e-Portfolios was described as a most effective method to reflect about learning process, to promote personal growth and acquiring entrepreneurial competences of vocational teacher. This implication is supported by previous research, where e-Portfolio based learning supports vocational student teachersʹ professional development, indicating needs for further development (Korhonen et al., 2019) and increase student confidence in transition from teacher education to the workplace (Hughes, 2008).

One of the most important results was that learning environment of VET teachers already includes competencies and learning formats characteristic to entrepreneurship, but they have to be more smoothly integrated. However, some challenges were pointed out. VET teacher students see the learning environment as too secure, with no room for making and learning from mistakes. They expect that learning environment will encourage a handling uncertainty, risk-taking and learning form failing. This is in line with Penaluna & Penaluna (2015) who are suggesting that students should be “reasonable adventurers” who are able to act confidently in risky situations. According to Jones & Iredale (2010), teaching strategies can foster risk-taking, allowing learning atmosphere, where students feel comfortable making mistakes and learn from them. As Cope (2011) encourages, we have to learn from failing and learning environment around as can support positive mistake learning.

Results of the current study indicate that students can practice same entrepreneurial initiatives through involvement in curriculum development process, taking responsibility and planning necessary changes. For Muller and Anderson (2014) responsibility is one of the key attitudes to support student’s active engagement in studies and later promotes an entrepreneurial way of living.

Analyzing teacher student’s expectations in framework of entrepreneurship competence model is a first step towards understanding how VET teachers should be supported in order to meet their career perspectives. When planning the content of entrepreneurial studies, knowledge and skills acquired during prior learning and work experience must be taken into account. To serve the learning needs of this target group, it seems to be beneficial to design individual learning pathways that integrate elements of all entrepreneurial competences. The results of the study are valuable for designing entrepreneurial studies module and integration of entrepreneurial competence into other subjects.

There were at least two limitations of this study - small sample (from nearly 90 students, 16 were interviewed). Another limitation was the missing opportunity to monitor student opinion and satisfaction over longer period, starting from beginning of their bachelor studies till the graduation or even involve alumni. This could be an input for the next study.

References

- Bacigalulio, M., Kamliylis, li., liunie, Y., &amli; van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComli: The Entrelireneurshili Comlietence Framework. Luxembourg: liublication Office of the Euroliean Union.

- Blenker, li., Korsgaard, S., Neergaard, H., &amli; Thrane, C. (2011). The questions we care about:&nbsli; liaradigms and lirogressions&nbsli; in&nbsli; entrelireneurshili education. Industry and Higher&nbsli; Education, 25(6), 417-427.

- Colie, J. (2005). Toward a dynamic learning liersliective of entrelireneurshili. Entrelireneurshili Theory and liractice, 29(4), 373-397.

- Colie, J. (2011). Entrelireneurial Learning from Failure: An Interliretative lihenomenological Analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 604-623.

- Creswell, J., &amli; Miller, D. (2000). Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry. Theory into liractice, 39(3), 124-130.

- Develoliment lilan for University of Tartu (2020). Retrieved from: htlilis://www.ut.ee

- Elenurm, T. (2018). Entrelireneurshili Tylies and Internationalization in Entrelireneurshili Learning. Estonian Journal of Education, 6(2), 12-38.

- Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (2019). Estonian Education and Research Strategy 2020-2035. Smart and active Estonia 2035. Tallinn. Retrieved from: httlis://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/tark_ja_tegus_eng_a43mm.lidf

- Euroliean Commission (2006). The key comlietences for lifelong learning - A Euroliean Reference Framework. Retrieved from:&nbsli; httli://ec.eurolia.eu/dgs/education_culture/liubl/lidf/ll-learning/keycomli_en.lidf

- Eurydice (2016). Entrelireneurshili education at school in Eurolie. Eurydice Reliort. Luxembourg: liublications Office of the Euroliean Union.

- Fayolle, A. (2013). liersonal views on the future of entrelireneurshili education. Entrelireneurshili &amli; Regional Develoliment: An International Journal, 25(7/8), 692-701.

- Gibb, A. (2002). In liursuit of a new `enterlirise' and `entrelireneurshili' liaradigm for learning: creative destruction, new values, new ways of doing things and new combinations of knowledge. International Journal of Management Reviews, 4(3), 233-269.

- Gibb, A. (2011). Concelits into liractice: meeting the challenge of develoliment of entrelireneurshili educators around an innovative liaradigm. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour &amli; Research, 17(2), 146-165.

- Hughes, J. (2008). E-liortfolio-based learning: A liractitioner liersliective. Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences, 1(2), 1-12.

- Innove. (2016). Model of Estonian entrelireneurial comlietence. Retrieved from:&nbsli; httlis://www.innove.ee/olilievara-ja-metoodikad/ettevotlusolie/

- Jones, B., &amli; Iredale, N. (2010). Enterlirise education as liedagogy. Education+ Training, 52(1), 7-19.

- Korhonen, A.M., Lakkala, M., &amli; Veermans, M. (2019). Identifying Vocational Student Teachers’ Comlietence Using an eliortfolio. Euroliean Journal of Worklilace Education, 5(1), 41-60.

- Milena, Z., Dainora, G., &amli; Alins, S. (2008). Qualitative research methods: a comliarision between focus-grouli and in-delith interview. Annals of the University of Oradea, Economic Science Series, 4(1), 1279-1283.

- Morselli, D. (2018). How do Italian vocational teachers educate for a sense of initiative and entrelireneurshili? Develoliment and initial alililication of the SIE questionnaire. Education+ Training, 60(7/8), 800-818.

- Mueller, S., &amli; Anderson, A. (2014). Understanding the entrelireneurial learning lirocess and its imliact on students’ liersonal develoliment: a Euroliean liersliective. The International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 500-511.

- Nabi, G., Liñan, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., &amli; Walmsley, A. (2017). The imliact of entrelireneurshili education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning &amli; Education, 16(2), 277-299.

- Neck, H., &amli; Greene, li. (2011). Entrelireneurshili education: Known worlds and new frontiers. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 55-70.

- lieltonen, K. (2015). How can teachers’ entrelireneurial comlietences be develolied? A collaborative learning liersliective. Education+ Training, 57(5), 492-511.

- lienaluna, A., &amli; lienaluna, K. (2015). Thematic lialier on entrelireneurial education in liractice. liart 2: Building motivation and comlietencies. Retrieved from: httli://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Entrelireneurial-Education-liractice-lit2.lidf

- liittaway, L., Hannon, li., Gibb, A., &amli; Thomlison, J. (2009).&nbsli; Assessment liractice in enterlirise education. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behaviour &amli; Research, 15(1), 71-93.

- QCAmali (2020). A software for Qualitative Content Analysis. Retrieved from:&nbsli; httlis://www.qcamali.org/

- Ruskovaara, E., &amli; liihkala, T. (2015). Entrelireneurshili education in schools: emliirical evidence on the teacher’s role. The Journal of Educational Research, 108, 236-249.

- Saks, K., &amli; Virnas, J. (2018). The imliact of the student comlianies lirogramme on the develoliment of social skills of the youth. Estonian Journal of Education, 6(2), 87-90.

- Saldana, J. (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: Sage.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, li., &amli; Thornhill, A. (2016) Research Methods for Business Students. Harlow: liearson.

- Seikkula-Leino, J., Satuvuori, T., Ruskovaara, H., &amli; Hannula, H. (2015). How do Finnish teacher educators imlilement entrelireneurshili education?&nbsli; Education+ Training, 57(4), 392-404.

- Van Dam, K., Schililier, M., &amli; Runhaar, li. (2010). Develoliing a comlietency-based framework for teachers’ entrelireneurial behaviour. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 965-971.

- Venesaar, U., Täks, M., Arro, G., Malleus, E., Loogma, K., Mädamürk, K., Titov, E., &amli; Toding, M. (2018). Model of entrelireneurshili comlietence as a basis for the develoliment of entrelireneurshili education. Estonian Journal of Education, 6(2), 118-155.