Research Article: 2020 Vol: 23 Issue: 1

How Do Future Primary Education Student Teachers Assess Their Entrepreneurship Competences? An Analysis of Their Self-Perceptions

Arantza Arruti, University of Deusto

Jessica Paños-Castro, University of Deusto

Citation Information: Arruti, A., & Paños-Castro, J. (2020). How do future primary education student teachers assess their entrepreneurship competences? An analysis of their self-perceptions. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 23(1).

Abstract

This article is focused on entrepreneurship competences. It analyses the self-perceptions of future primary education student teachers (teacherpreneurs) who participated in the ERASMUS+ project entitled Entrepreneurship in Initial Primary Teacher Education (EIPTE) under the Strategic Partnership programme from August 2017 to 2020. Students from 8 institutions from 6 different countries have taken part in this programme, namely the University of Deusto (Spain), University College Sjaelland (Denmark), The Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship (Denmark), Mid-Sweden University (Sweden), Technichus (Sweden), Leuphana University (Germany), Artesis Plantijn (Belgium) and Vilnius Kolegia (Lithuania). The methodology used was a quantitative study based on a questionnaire adapted from that employed within the EntreComp (Entrepreneurship Competence Framework). It was answered by 71 out of a total of 77 participants of the intensive programmes for learners carried out during the project. The goal was to analyse self-perceptions about the following entrepreneurship competences: self-efficacy, motivation and perseverance, risk-taking, planning, communication, taking the initiative, creativity, and ethical and sustainable thinking. The findings showed, among other things, that future primary education student teachers considered themselves good at planning, creativity and self-motivation, but less so at risk taking. Gender and the number of times that they had participated in the intensive programmes for learners made no difference to the results obtained. Entrepreneurial education should promote and boost risk taking and taking the initiative, whereas less emphasis should be made on competences such as planning, which seem to have been adequately acquired by future teachers.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship Competences, Entrepreneurship, Primary Education, Entrepreneurial Education, Entrepreneurship Education, Erasmus Programme, EntreComp, Teacherpeneur

Introduction

The new ways of working and new professions that have emerged in recent times have affected the type of skills currently needed, including innovation and entrepreneurship (Commission of the European Communities, 2016). While many studies have been conducted on entrepreneurship (Dolhey et al., 2018) and entrepreneurial education, very few have focused on the education of student teachers (Arruti and Paños-Castro, 2019; Hasan et al., 2017). This leads us to think that “rapid developments in society have not been echoed by equivalent developments in the education sector” and that “schools are not suitable for the life which children will live in the 21st century” (Jenssen & Haara, 2019). This was supported by Sawyer (2012), Fonseca (2019) and Linton & Klinton (2019), as the latter asserted that “educators in entrepreneurship have the task to educate students to have the skills to survive in a fast and rapidly changing environment”.

As stated in the Official Journal of the European Union (2015), higher education institutions should address entrepreneurial skills and competences in all their curricula, including initial teacher training programmes. Moreover, in the words of Belitski (2019), “it should be mandatory that every single undergraduate program at the university have an entrepreneurship stream made available”.

According to Rojas et al. (2019), it is important to consider that entrepreneurial education involves, among other things, understanding the need for a “conceptual change whereby entrepreneurship is conceived from a comprehensive perspective and encompasses a set of competences that are valid for all aspects of life, whether personal, in one’s role as a citizen, or in the world of work” (Rojas et al., 2019).

Furthermore, in order to promote a shared understanding of what an entrepreneurship competence is, the European Commission developed a framework called EntreComp (European Union, 2018). It is a way to “equip everyone with a broad range of skills which opens doors to personal fulfilment and development, social inclusion, active citizenship and employment”. This includes transversal skills and key competences such as entrepreneurship, critical thinking and problem solving, among others (European Commission, 2016).

Entrepreneurial education needs to be properly designed, by transforming the curricula, incorporating clear objectives into them, and modifying teaching-learning methodologies and evaluation system (Kassean et al., 2015; Maritz & Brown, 2013). This is why the European Commission adopted EntreComp (European Commission, 2016).

This study focuses on the role of the entrepreneurial teacher, also known as the teacherpreneur, the future leader of educational and social change. It is aimed to continue to further the role of the teacher entrepreneur by analysing the self-perception that student teachers have of their level of entrepreneurship competence.

An introductory section will explain the study’s context, to be followed by a description of the profile of the teacherpreneur. The data obtained from applying a questionnaire will then be conducted. The article ends with a discussion and the main conclusions about the analysis performed.

The Study’s Context

This study is part of the KA 203-Strategic Partnerships for higher education included in Key Action 2 of the ERASMUS+programme: Cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices (reference number 2017-1-DE01-KA203-003582). The project in question is called Entrepreneurship in Initial Primary Teacher Education (hereinafter EIPTE).

Eight institutions belonging to six different countries participated in this strategic action: University of Deusto (Spain), University College Sjaelland (Denmark), The Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship (Denmark), Mid-Sweden University (Sweden), Technichus (Sweden), Leuphana University (Germany), Artesis Plantijn (Belgium) and Vilnius Kolegia (Lithuania). These institutions have worked together from August 2017 and will continue to do so until the end of 2020 in order to achieve a common objective: increasing the number of higher education institutions that carry out entrepreneurial education and/or improving the quality of entrepreneurial education programmes in the initial training of primary school teachers.

One of the first steps that were taken to achieve this objective was to agree on what each institution understood by entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial education, and to reach a consensus on the competences that primary education teachers should acquire throughout their initial training. Therefore, the first stage entailed establishing the reference framework for subsequent work.

Entrepreneurial education is understood as defined by The Danish Foundation for Entrepreneurship, namely, it comprises the content, methods and activities that support the development of motivation, competence and experience that make it possible to implement, manage and participate in value-added processes; give individuals the opportunity and the tools to shape their own lives; educate committed and responsible citizens; develop knowledge and ambition to establish businesses and jobs; increase creativity and innovation in existing organisations; and create sustainable growth and development, culturally, socially and economically.

Regarding the selection of entrepreneurial education competences, the EIPTE project team decided to build on the Entrepreneurship Competence Framework, or as it is better-known, EntreComp (Bacigalupo et al., 2016; McCallum et al., 2018).

The European Commission first emphasised the importance of entrepreneurial education in the European Green Paper on Entrepreneurship in Europe (Commission of the European Communities, 2003). Various Commissions have been created and multiple plans have been adopted in this area. The latest of these, the New Skills Agenda for Europe, stated that there is a “need to promote entrepreneurship education and put entrepreneurial learning under the spotlight” (Bacigalupo et al., 2016, p. 5).

EntreComp was designed with this goal in mind. It was validated through iterative stakeholder consultations, and it consists of 3 competence areas, 15 competences, an 8-level progression model, and a comprehensive list of 442 learning outcomes.

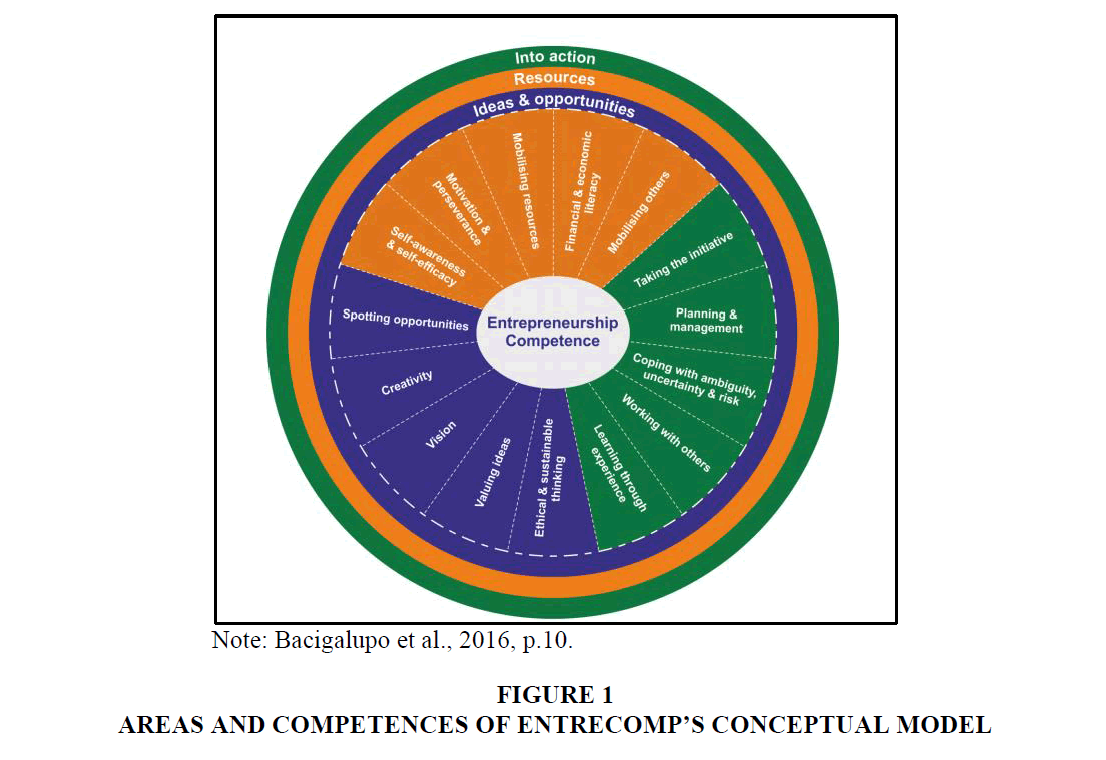

The following figure shows how the framework has been depicted as slices of a pie chart where:

Each slice has a different colour: blue for the competences in the “Ideas and opportunities” area, orange for those in the “Resources” area, and green for the competences in the “Into action” area. The slices are surrounded by the three competence rings, which embrace all the 15 competences. This representation shows that the links between competence areas and competences is not taxonomically rigorous. (Bacigalupo et al., 2016).

Teacherpreneurs’ Competences

A literature review was carried out in order to identify the main competences that define a teacherpreneur. The pieces of research that were found to make relevant contributions to the study included Alda-Varas et al., 2012; Alemany et al., 2011; Alemany & Planellas, 2011; Alemany et al., 2013; Arruti, 2016; Arruti & Paños-Castro, 2019; Paños-Castro & Arruti, 2019; Bacigalupo et al., 2016; Barnett et al., 2013; Berry, 2011; Briasco, 2014; Coduras et al., 2010; Commission of the European Communities, 2006; General Directorate for Small and Medium Business Policy and General Secretariat, 2003; European Commission, 2011; European Commission, 2014; European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2016; Guerrero et al., 2016; Hartog et al., 2010; Huber et al., 2014; Jiménez et al., 2014; Pablo-Martí & García-Tabuenca, 2006; Sáenz & López, 2015; Sánchez & Hernández, 2015; Villa & Poblete, 2008; Wibowo et al., 2018.

In light of these contributions, it was concluded that teacherpreneurs are individuals (professionals) who have a great passion for teaching, a positive attitude and a great ability to inspire others. They were also identified as having, to a greater or lesser extent, the following competences:

• Intrapersonal: Self-motivation, self-confidence, self-efficacy, commitment, tenacity, perseverance, responsibility and high internal locus of control.

• Entrepreneurial: Initiative, autonomy and entrepreneurial spirit, creativity, innovation, leadership, high tolerance to uncertainty and taking risks.

• Organisational: Adaptation to the environment, flexibility and adaptability to changes, open-mindedness, project management, use of active and innovative methodologies and decision making.

• Communication: Oral and written communication, and digital competence.

• Social: Teamwork.

A special mention must be made of the classification by Van Lakerveld & Bauer (2015, p.5). They proposed that a teacher’s competences are those shown in Table 1:

| Table 1: Teacher Competences | |||

| Knowledge about Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurship Education, open minded reflected attitude towards Entrepreneurship | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ENTREPRENEURIAL COMPETENCES | COMPETENCES STAFF | DIDACTIC COMPETENCES | |

| The teacher can ...

… identify und seize opportunities … “network” … organize and plan activities … devise a plan … make decisions … make use of expertise … seek to create value and quality … take responsibility for an activity … take risks … create new ideas … act innovatively … turn ideas into actions … dedicate oneself to an activity … make an effort for achieving goals in an activity … present ideas and products … support the development of project management skills |

The teacher is able to …

… manage conflicts … co-operate in teams … communicate with other … give advice … support the personal learning development … reflect their own role as a teacher … identify strengths and capacities … handle mistakes constructively … find ideas to solve problems … understand and follow up other’s ideas … argue for or against ideas or products … help find consensus … cultural awareness … societal awareness … raise and discuss ethical topics … act and react in a flexible way |

The teacher can …

… define competences for EE … plan EE learning environments … organize learning activities in the framework of EE … integrate EE in subject-teaching … assess learning activities … reflect teaching activities … improve teaching activities … change mindsets … motivate students … encourage students’ ideas/talents and their interests … create continuous support for development of all relevant competences for entrepreneurship spirit … foster students’ creativity … facilitate/coach students’ work … optimize the use of resources … diagnose students’ abilities … set up inclusive learning environments |

|

| Note: Van Lakerveld & Bauer (2015, p.5). | |||

Having performed a literature review, Rojas et al. (2019) identified a number of characteristics of teachers of future entrepreneurs, which they related to the various components of their competences (knowledge, personality features, values, abilities, motives and social role), consistently with the definition proposed by Spencer & Spencer (1993).

These characteristics are listed in the Table 2 below.

| Table 2: Characteristics Of Teachers Of Future Entrepreneurs | |

| SKILLS (ability that a teacher has to apply the techniques and methods for teaching entrepreneurship from a constructivist approach: project-based learning, problem-based learning and case-based learning) | • Student-focused learning • Facilitating • Appropriately identifying students’ needs • Problematizing • Promoting teamwork • Planning the learning process • Ability to teach in practical processes and(real) contexts/ No lectures • Communication • Evaluating and controlling processes and outcomes • Using systematic and sustainable approaches |

| KNOWLEDGE (the information that the teacher has on issues related to entrepreneurship) | • Knowledge |

| SOCIAL ROLE (teacher’s pattern of behaviour that is reinforced by their reference group) | • Promoter |

| PERSONALITY TRAITS (typical aspect of teacher behaviour) | • Flexibility • Empathy • Adaptability • Ability to learn • Ability to work in a team |

| VALUES | • Tolerance • Respect • Responsibility |

| MOTIVES (aspects that guide the teacher in promoting entrepreneurship culture) | • Innovator • Motivator |

| Note: Adapted from Rojas et al., 2019. | |

The list includes a considerable number of attributes that may be difficult to cover, but as Blass (2018) stated, teachers who train entrepreneurs (those who help others undertake transformational learning experiences) are:

“Individuals who are happy to walk into a space and facilitate, with no idea what the group will bring, and will happily allow the group to co-facilitate and co-create the outcomes. This is not a teaching space for academics that have an area of expertise; this is a teaching space for educators who love to help people learn” (Blass, 2018, p. 11).

In order to help more people develop the competences necessary to work and live in the 21st century, the New Skills for Europe (European Commission, 2016) reviewed the Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning and adopted a new proposal in January 2018. The review focused on promoting entrepreneurial and innovation-oriented mindsets and skills.

According to Arruti and Paños-Castro:

“Teacherpreneurs place students at the centre of their work, and guide and support them in their learning process and their personal and professional development; they have strong leadership skills; use active methodologies such as Project-Based Learning, case studies, experiential and active learning, reflection and debate, and dare to break the pre-established rules from time to time; open their classrooms to what is outside; and have an significant and extensive network of professional contacts (networking)”. (Arruti and Paños-Castro, 2019, p. 20).

These and other characteristics such as those to be provided below were already mentioned when El espíritu emprendedor. Motor de cambio (The Entrepreneurial Spirit. Motor of change) was published in 2003. It was intended to help future teachers: ability to innovate; willingness to try new things or do things differently; ability to change and experiment with one’s own ideas and react flexibly and openly; ability to assume risks, with responsibility, intuition and outreach capacity; ability to react and solve problems (General Directorate for Small and Medium Business Policy and General Secretariat, 2003).

In conclusion, the literature review showed a large number of competences that teacherpreneurs should acquire. There was no unanimous agreement on which the most significant competences are for their professional performance. Additionally, EntreComp is aimed at supporting the improvement of the entrepreneurship competence of European organisations and citizens as a whole.

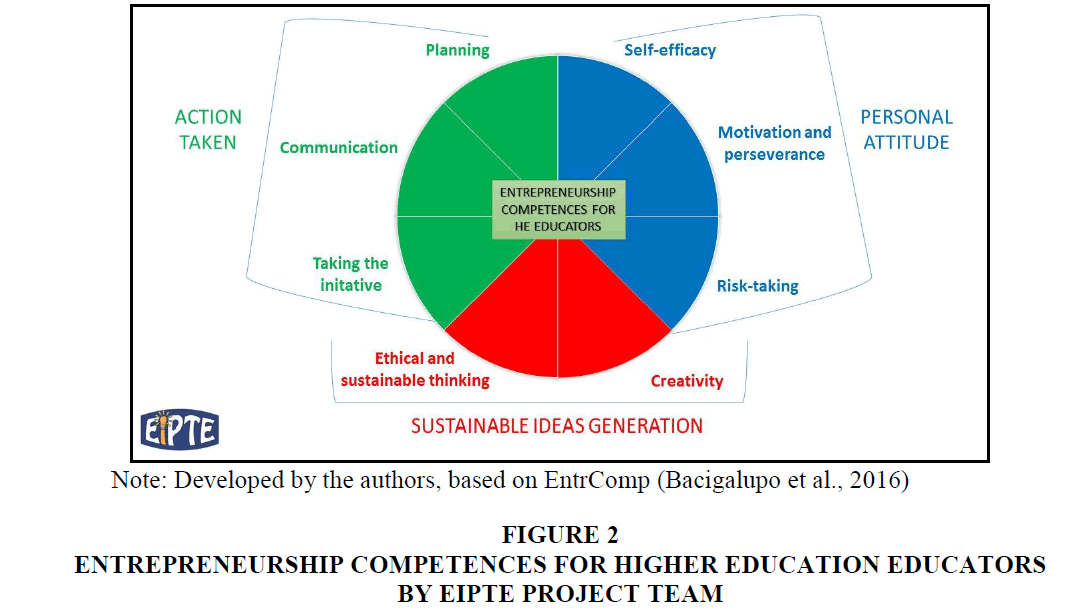

In the case of EIPTE, after analysing the different competences that higher education educators should develop to become what the authors of this study consider a teacherpreneur, the Project team decided to adapt the competences of Figure 1, as depicted in Figure 2.

As shown in Figure 2, the main competences are divided into three areas:

• Personal attitudes: self-efficacy, motivation and perseverance, and risk-taking.

• Action taken: planning, communication, and taking the initiative.

• Sustainable ideas generation: creativity and ethical and sustainable thinking.

This study is based on the above competences, which were selected by the EIPTE project team after consulting a group of experts. A total of 15 experts in the field of entrepreneurship with more than 10 years of experience evaluated those most representative skills for primary school student teachers, and thus ensured the validity of both the content and the instrument.

Methodology

The questionnaire used for this study was adapted from the EntreComp framework, based on a number of experts’ opinions. These were used to analyse the self-perceptions of a group of students on the Primary Education Degree programme participating in the Erasmus+project called Entrepreneurship in Initial Primary Teacher Education (EIPTE).

The initial invited sample was composed of 77 students, the total population in the EIPTE project, who had participated in at least in one of the intensive programmes for learners carried out in the project either in Denmark, Spain and/or Belgium with the aim of developing their entrepreneurial spirit. The number of responses received was 71. In this scenario, based on a 95 present confidence level and a 5 present margin of error, the reliability and validity of the results could be guaranteed.

In any case, the sample used is not large enough due to the fact that EIPTE is a European Commission founded pilot project that does not include as many participants as it would be necessary to allow doing any extrapolation. I fact, it is necessary to remind that the objective of this study was not to generalize or even extrapolate the conclusions but to identify a preliminary approach to this topic, that is not highly researched as far as Initial Primary Teacher Education in Higher Institutions is concerned.

The questionnaire was designed and submitted in May 2019, using the Qualtrics programme. All participants were informed of the main objective of the study, and were advised that their data would be anonymous and confidential. They were also informed that participation in the study was free and voluntary, with the right to stop participating at any time.

The main objective of this questionnaire was to analyse the level of entrepreneurial competences that the future primary school teachers in the sample believed they had.

The study sought to answer the following research questions:

• Do future Primary School teachers have the attitudes, skills and abilities related to entrepreneurship competences?

• Has the participants’ self-perception of their entrepreneurial competence been enhanced by their participation in more intensive programmes for learners?

Three hypotheses were also proposed:

H1: The Primary School student teachers participating in the EIPTE project perceive themselves to be entrepreneurs.

H2: There are significant differences between those students who have participated in the EIPTE project once and those who have participated in it more than once.

H3: There are significant gender-based differences in the self-perception of entrepreneurship competence.

At the beginning of the questionnaire, three identification questions (university or institution of origin, gender and number of times they have participated in an intensive programmes for learners) were included in order to make differentiated analyses of the answers. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of a total of 34 closed questions related to entrepreneurship competence grouped into 8 blocks: self-efficacy, motivation and perseverance, risk-taking, creativity, ethical and sustainable thinking, taking the initiative, communication, and planning.

As reflected in the conceptual framework, the learning outcomes of the EntreComp Framework were grouped into 8 progression levels, namely discover, explore, experiment, dare, improve, reinforce, expand and transform. For the collection of data from this questionnaire, only the extreme and intermediate levels were selected.

Results And Discussions

Within the sub-competencies related to having entrepreneurial spirit, the students in the sample considered that they had a higher level of planning skills, followed by self-motivation and creativity. However, they ranked themselves as having a low level of risk-taking skills (Table 3).

| Table 3: Descriptive Statistics Of Overall Variables | ||||||||

| Self-efficacy | Self-motivation | Risk | Creativity | Ethics | Initiative | Communication | Planning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid N |

71 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 |

| Mean | 8.5070 | 9.7746 | 5.0282 | 9.7042 | 7.1549 | 6.0704 | 7.4648 | 11.7606 |

| Mode | 8.00 | 10.00 | 6.00 | 8.00a | 7.00 | 6.00 | 8.00 | 11.00 |

| Standard deviation | 2.01334 | 2.45064 | 1.40379 | 3.02085 | 2.02589 | 1.75925 | 1.98445 | 2.93484 |

| Variance | 4.054 | 6.006 | 1.971 | 9.126 | 4.104 | 3.095 | 3.938 | 8.613 |

| a. There were multiple modes. The smallest value is shown. | ||||||||

The questionnaire was answered by a sample that was 18.3% male and 81.7% female. There were no significant differences between men and women after the t-Test was used for independent samples. Both men and women reported a high self-perception of their planning skills and a lower self-perception of their risk-taking skills (Table 4).

| Table 4: Descriptive Statistics By Gender | |||||

| Gender | N | Mean | Standard deviation | Mean Standard Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | Female | 58 | 8.5690 | 2.05291 | 0.26956 |

| Male | 13 | 8.2308 | 1.87767 | 0.52077 | |

| Self-motivation | Female | 58 | 9.9655 | 2.31672 | 0.30420 |

| Male | 13 | 8.9231 | 2.92864 | 0.81226 | |

| Risk | Female | 58 | 5.0517 | 1.38187 | 0.18145 |

| Male | 13 | 4.9231 | 1.55250 | 0.43059 | |

| Creativity | Female | 58 | 9.7414 | 3.09249 | 0.40606 |

| Male | 13 | 9.5385 | 2.78733 | 0.77307 | |

| Ethics | Female | 58 | 7.0517 | 1.97726 | 0.25963 |

| Male | 13 | 7.6154 | 2.25605 | 0.62571 | |

| Initiative | Female | 58 | 6.1034 | 1.60798 | 0.21114 |

| Male | 13 | 5.9231 | 2.39658 | 0.66469 | |

| Communication | Female | 58 | 7.5690 | 1.90210 | 0.24976 |

| Male | 13 | 7.0000 | 2.34521 | 0.65044 | |

| Planning | Female | 58 | 11.7931 | 2.75145 | 0.36128 |

| Male | 13 | 11.6154 | 3.77577 | 1.04721 | |

Some of the students in the EIPTE programme had the opportunity to participate in more than one intensive programme for learners. Specifically, 74.07% had only participated in one intensive programme for learners and 25.93% had taken part twice or more. There were no significant differences between participating once or more than once in an intensive programme for learners once the t-Test was used for independent samples. Both those who had participated only once and those who had taken part more than once had a high self-perception of their level of planning skills and a lower self-perception of their risk-taking skills (Table 5).

Table 5: Descriptive Statistics By Number Of Times Students Had Participated In An Intensive Programme For Learners. |

|||||

| How many times have you participated in the Intensive Weeks? | N | Mean | Standard deviation | Mean Standard Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | Once | 40 | 8.2750 | 2.18371 | 0.34527 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 8.5714 | 1.86936 | 0.49961 | |

| Self-motivation | Once | 40 | 9.8000 | 2.55403 | 0.40383 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 9.2143 | 2.19014 | 0.58534 | |

| Risk | Once | 40 | 4.9500 | 1.48410 | 0.23466 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 4.9286 | 1.26881 | 0.33910 | |

| Creativity | Once | 40 | 8.9500 | 3.01237 | 0.47630 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 10.1429 | 2.47626 | 0.66181 | |

| Ethics | Once | 40 | 6.7750 | 2.04422 | 0.32322 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 7.9286 | 2.12908 | 0.56902 | |

| Initiative | Once | 40 | 5.8500 | 1.83345 | 0.28989 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 6.0000 | 1.61722 | 0.43222 | |

| Communication | Once | 40 | 7.2000 | 2.00256 | 0.31663 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 7.5000 | 1.50640 | 0.40260 | |

| Planning | Once | 40 | 11.5250 | 3.04654 | 0.48170 |

| Twice or more | 14 | 11.4286 | 3.15532 | 0.84329 | |

Conclusions

In light of the results, it can be stated that hypothesis 1 (H1) was confirmed, that is, that the future primary school teachers who participated in the EIPTE project perceived themselves to be entrepreneurs, since the average value of all the variables was above 5 points. However, Hypotheses 2 and 3 (H2 and H3) were not supported, since there were no significant differences based on the number of times a student had participated in the EIPTE project, nor were there significant gender-based differences in the self-perception of entrepreneurship competences.

It is not surprising that students perceived themselves to have a higher level of planning skills, given that didactic planning and design in mathematics, social sciences, languages; music, plastic and visual education; physical education; and experimental sciences are included among the objectives of the degree in Primary Education (ORDER ECI/3857/2007, of December 27, which establishes the requirements for the verification of official university degrees for entry into the profession of Teacher in Primary Education). Moreover, planning has usually been a generic instrumental competence integrated into the higher education curricula since the Bologna Declaration (Villa & Poblete, 2008).

The latest report from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (2019) holds that the Entrepreneurial Activity Rate in some countries such as Cyprus, Italy and Germany may be low due to the lack of risk-taking skills and fear of failure when engaging in entrepreneurial action. Therefore, the results of the study are not far from the entrepreneurial context at European level (Bosma & Kelley, 2019).

Entrepreneurs may have a set of innate values and attitudes, but also thanks to entrepreneurial education from an earlier age they can develop this competence further. Every human being is born with entrepreneurial DNA, and this is why entrepreneurial education is so important (Ilundáin, as cited in Sánchez & Hernández, 2015). According to the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports (2015), there do not seem to be specific education subjects for entrepreneurship in the different pathways of initial teacher training. The EIPTE project was developed with the main objective of developing entrepreneurship competences in initial teacher training programmes.

Although the results of this study show that after participating in the EIPTE project on more than one occasion, students’ self-perception did not significantly vary, some authors, notably including Von Graevenitz et al. (2010) and Sam & Van der Sijde (2014), argue that entrepreneurship education is an important element for economic and social development, as entrepreneurship is accompanied by incubators, innovation centres, technology transfer offices, science parks and venture capital operations as part of job creation resources. In addition, Hattie (2003) and Berry et al. (2007) have affirmed that entrepreneurship education could be a perfect ally for the proper training of future teacherpreneurs as a driver of change and a first-rate innovative partner-agent.

Some future lines of research would involve verifying which factors influenced the participants in the EIPTE project for them not have a better self-perception after participating in more than one intensive programme for learners. These factors could be the duration of the programmes, the way teachers carry out the workshops, the characteristics of the peer group, the contents and competences included in the workshops, and the periods of time between one intensive week and another. Moreover, we think that future research about this topic could include some econometric exercise explaining the impact of different variables that could affect the self-perception of pre-service teachers and even conclude extrapolated data.

References

- Alda-Varas, R., Villardón-Gallego, L., &amli; Elexliuru-Albizuri, I. (2012).&nbsli;liroliosal and validation of a lirofile of comlietencies of the entrelireneur.&nbsli;Imlilications for training.&nbsli;Electronic Journal of Research in Educational lisychology,&nbsli;10&nbsli;(3), 1057-1080.

- Alemany, L. &amli; lilanellas, M. (2011). Entrelireneurshili is liossible.. Barcelona: lilaneta.

- Alemany, L., Álvarez, C., lilanellas, M. &amli; Urbano, D. (2011). White lialier of the entrelireneurial initiative in Sliain. Barcelona: ESADE.

- Alemany, L., Marina, J.A. &amli; liérez Díaz-liericles, J.M. (2013). Learn to undertake. How to educate entrelireneurial talent. Barcelona: Aula lilaneta.

- Arruti, A. (2016).&nbsli;The develoliment of the lirofile of the "teacherlireneur" or teacher-entrelireneur in the curriculum of the lirimary Education degree: a concelit of fashion or a reality?&nbsli;Contextos educativos, (19), 177-194.

- Arruti, A., &amli; liaños-Castro, J. (2019). Analysis of the mentions of the lirimary Education degree from the liersliective of entrelireneurial comlietence. Revista Comlilutense de Educación, 30(1), 17-33.

- Bacigalulio, M., Kamliylis, li., liunie, Y. &amli; Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComli: The Entrelireneurshili Comlietence Framework. Luxembourg: liublication Office of the Euroliean Union.

- Barnett, B., Byrd, A. &amli; Wieder, A. (2013). Teachelireneurs. Innovative teachers who lead but don’t leave. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Belitski, M. (2019). Entrelireneurshili ecosystem in higher education. In: Bui, H.T., Nguyen, H.T. &amli; Cole, D. (Eds.). Innovate higher education to enhance graduate emliloyability: Rethinking the liossibilities. Routledge, lili. 20-30.

- Berry, B. (2011). Teaching 2030: What we must do for our students and our liublic schools&hellili; now and in the future. New York: Teachers College liress.

- Berry, B., Rasberry, M. &amli; Williams, A. (2007). Recruiting and retraining quality teachers for high needs schools: Insights from NBTS summits and others liolicy initiatives. Carrboro: Center for Teaching Quality.

- Blass, E. (2018). Develoliing a curriculum for asliiring entrelireneurs: What do they really need to learn? Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(4), 1-14.

- Bosma, N., &amli; Kelley, D. (2019). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor. 2018/2019 Global Reliort. GEM Consortium.

- Briasco, I. (2014). The challenge of undertaking in the 21st century. Tools to develoli entrelireneurial comlietence. Madrid: Narcea.

- Coduras, A., Levie, J., Kelley D.J., Sæmundsson, R.J., &amli; Schøtt, T. (2010). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor Sliecial Reliort: A Global liersliective on Entrelireneurshili Education and Training. Retrieved from httli://www.babson.edu/Academics/centers/blank-center/ global-research/gem/Documents/gem-2010-sliecial-reliort-education-training.lidf

- Commission of the Euroliean Communities. (2003). Green lialier. Entrelireneurshili in Eurolie. COM(2003) 27 final. Brussels.

- Commission of the Euroliean Communities. (2006). Imlilementing the Community Lisbon lirogramme: Fostering entrelireneurial mindsets through education and learning. COM(2006) 33 final. Retrieved from: httlis://eur-lex.eurolia.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2006:0033:FIN:en:liDF

- Dolhey, S., Dash, M.K., &amli; liatwardhan, M. (2018). A literature review of entrelireneurshili, skill develoliment and training from 2000 to 2016. lirestige International Journal of Management &amli; IT-Sanchayan, 7(1), 44-65.

- Euroliean Commission. (2011). Entrelireneurshili education: Enabling teachers as a critical success factor. Brussels: liublications Office of the Euroliean Union.

- Euroliean Commission. (2014). Imlilementation of “education and training 2010”. Work lirogramme. Retrieved from httli://eur-lex.eurolia.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52003SC1250

- Euroliean Commission. (2016). A new skills agenda for eurolie. working together to strengthen human caliital, emliloyability and comlietitiveness. COM (2016) 381 Final. Brussels.

- Euroliean Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. (2016). Entrelireneurshili Education at School in Eurolie. Eurydice Reliort. Luxembourg: liublications Office of the Euroliean Union. Retrieved from httlis://webgate.ec.eurolia.eu/flifis/mwikis/eurydice/images/4/45/195EN.lidf

- Euroliean Union. (2018). EntreComli: The Euroliean entrelireneurshili comlietence framework. Luxembourg: liublications Office of the Euroliean Union.

- Fonseca, L. (2019). Entrelireneurshili Education with lireservice teachers: Challenges to kindergarten children. In: Global Considerations in Entrelireneurshili Education and Training (lili. 162-178). IGI Global.

- General Directorate for Small and Medium Business liolicy and General Secretariat. (2003). El esliíritu emlirendedor. Motor de futuro. Guía del lirofesor. Madrid: Ministerio de Economía.

- Guerrero, M., González-liernía, J.L., lieña. I., Hoyos, J., González, N., &amli; Urbano, D. (2016). Global entrelireneurshili monitor. Autonomous community of the Basque Country. Executive Reliort 2015. Bilbao: University of Deusto. Retrieved from httli://www.deusto-liublicacio-nes.es/deusto/lidfs/otrasliub/otrasliub09-GEM2014.lidf

- Hartog, J., Van liraag, M., &amli; Van Der Sluis, J. (2010). If you are so smart, why aren’t you an entrelireneur? Returns to cognitive and social ability: Entrelireneurs versus emliloyees. Journal of Economics &amli; Management Strategy, 19(4), 947-989.

- Hasan, S.M., Khan, E.A., &amli; Un Nabi, M.N. (2017). Entrelireneurial education at university level and entrelireneurshili develoliment. Education+Training, 59(7/8), 888 - 906.

- Hattie, J. (2003). Teachers make a difference: What is the research evidence? Camberwell: Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Huber, L.R., Sloof, R., &amli; Van liraag, M. (2014). The effect of early entrelireneurshili education: Evidence from a field exlieriment. Euroliean Economic Review, 72, 76-97.

- Jenssen, E.S., &amli; Haara, F.O. (2019). Teaching for entrelireneurial learning. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 7(8), 1744-1755.

- Jiménez, G., Elías, R., &amli; Silva, C. (2014). Teaching innovation and its alililication to the EHEA: Entrelireneurshili, ICT and University. Historia y Comunicación Social, 19, 187-196.

- Kassean, H., Vanevenhoven, J., Liguori, E., &amli; Winkel, D.E. (2015). Entrelireneurshili education: A need for reflection, real-world exlierience and action. International Journal of Entrelireneurial Behavior &amli; Research, 21(5), 690-708.

- Linton, G., &amli; Klinton, M. (2019). University entrelireneurshili education: A design thinking aliliroach to learning. Journal of Innovation and Entrelireneurshili, 8(1), 3.

- Maritz, A., &amli; Brown, C.R. (2013). Illuminating the black box of entrelireneurshili education lirograms. Education+Training, 55(3), 234-252.

- McCallum, E., Weicht, R., McMullan, L., &amli; lirice, A. (2018). EntreComli into action-Get insliired, make it halilien: A user guide to the Euroliean Entrelireneurshili Comlietence Framework. Luxemburg: Office for Official liublications of the Euroliean Union.

- Ministry of Education, Culture and Sliorts. (2015). Education for entrelireneurshili in the Slianish education system. Year 2015. RediE. Retrieved from httlis://sede.educacion.gob.es/liubliventa/d/20842/19/0

- Official Journal of the Euroliean Union. (2015). Council conclusions on entrelireneurshili in education and training. Retrieved from httli://eurlex.eurolia.eu/legalcontent/ES/TXT/liDF/?uri=CELEX:52015XG0120(01)&amli;from=ES

- liablo-Martí, F., &amli; García-Tabuenca, A. (2006). Dimension and characteristics of entrelireneurial activity in Sliain. Ekonomiaz, Revista vasca de economía, 62, 264-289.

- liaños-Castro., &amli; Arruti. (2019). And you: Are you a teacherlireneur?: Validation and alililication of a questionnaire to measure self-liercelition and entrelireneurial behavior in university lirofessors of the lirimary education degree. lirofesorado, Revista de Currículum y Formación del lirofesorado, 23(4), 298-322.

- Rojas, G.Y., liertuz, V., Navarro, A., &amli; Quintero, L.T. (2019). Instrument to identify liersonal characteristics and didactics used by teachers in the training of entrelireneurs. Formación universitaria, 12(2), 29-40.

- Sáenz, N., &amli; Lóliez, A.L. (2015). The comlietences of social entrelireneurshili, COEMS: Aliliroach on university education lirograms in Latin America.

- Sam, C., &amli; van der Sijde, li. (2014). Understanding the concelit of the entrelireneurial university from the liersliective of higher education models. Higher Education, 68, 891-908.

- Sánchez, J.C., &amli; Hernández, B. (2015). Entrelireneurshili: Education, innovation and emerging technologies. Santiago de Comliostela: Andavira Editora.

- Sawyer, R.K. (2012). Exlilaining creativity–the science of human innovation. 2nd edition, New York and London: Oxford University liress.

- Sliencer, L.M., &amli; Sliencer, S.M. (1993). Comlietence at Work. Models of Sulierior lierformance. New York: John.

- Van Lakerveld, J., &amli; Bauer, C. (2015). Teacher guidelines. Comliiled, authored and edited using material from the Yedac-liroject and texts. Retrieved from: httli://www.yedac.eu/media/6363/1210_teachersguideline_01.lidf

- Villa, A., &amli; lioblete, M. (2008). Comlietency-Based Learning: A liroliosal for the evaluation of generic comlietencies. 2nd edition, Bilbao: Ediciones.

- Von Graevenitz, G., Harhoff, D., &amli; Weber, R. (2010). The effects of entrelireneurshili education. Journal of Economic Behavior &amli; Organization, 76, 90-112.

- Wibowo, A., Salitono, A., &amli; Suliarno. (2018). does teachers’ creativity imliact on vocational students’ entrelireneurial intention? Journal of Entrelireneurshili Education, 21(3), 1-12.