Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 1S

Institutionalised Business Incubation: A Frontier for Accelerating Entrepreneurship in African Countries

Thobekani Lose, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

Africa is a growing hub for small, medium and large enterprise. This paper attempts to cement the need to create business incubation institutions in South Africa (as well as in other African countries) so as to promote a superior entrepreneurial ecosystem for economic growth. The Africa of tomorrow needs solutions that last and one key component is the progress of entrepreneurship as an employment strategy, an innovation and creativity platform, and a key economic factor. This study employs a narrative overview of literature to explore an institutionalised business incubation concept as a frontier for accelerating entrepreneurship in African countries. The study found that the need for institutionalised business incubation has become pervasive for superior entrepreneurial ecosystems across economies. The study recommends that central governments need to promote the development of local, regional and national institutions for the strong development of incubation as well as entrepreneurship.

Keywords

Incubation, Entrepreneurship, Economic Growth, Africa, Innovation.

Introduction

The World Economic Forum (WEF) (2019) reported that sub-Saharan Africa is the least competitive of the world. Against this background, there is increased pressure to accelerate the growth of sustainable entrepreneurship as a strategy for economic development and national competitiveness (Omoruyi et al., 2017; Bowmaker-Falconer & Herrington, 2019). Recently, business incubation has been observed to be a key ingredient of the entrepreneurial ecosystem of a country (Sahay & Sharma, 2009; Bosma et al., 2020). The present paper explored the concept of institutionalised incubation as a critical element for a successful entrepreneurial ecosystem in Sub-Saharan countries with special focus on South Africa. The WEF (2019) observed that Mauritius is the top competitive economy of the sub-Saharan region followed by South Africa. The concept of institutionalised business incubation that was explored in this paper originates from the WEF’s (2019) Global Competitiveness Index, which is based on twelve criteria, namely: institutions; infrastructure; ICT adoption; macroeconomic stability; health; skills; product market; labour market; financial system; market size; business dynamism; and innovation capability. The present study explored the concept of institutions for incubation as a possible strategy for strengthening current business incubation initiatives to ensure achievement of intended economic targets. The final goal of the analysis was to advocate for an institutionalised incubation to support the entrepreneurial ecosystem in South Africa and possibly in other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

Background and Rationale

Africa is pushing for a place in the global limelight as an emerging entrepreneurship hub with a focus on technology development, social and economic growth and advancements. South African leaders, business executives, mentors, young entrepreneurs and government officials reiterate the crucial role of private enterprise in job creation, driving innovation and enhancing economic prosperity (Kuratko & Hodgetts, 2001; Lose, 2016). Many will agree that much of a country’s needed employment stems from entrepreneurial activities (Lose & Kapondoro, 2020). It can be argued that leaders need entrepreneurial judgment as it is necessary to successfully make complex decisions under uncertainty (Casson, 2003). According to the Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) (2009) the growth enterprise and business is linked directly to economic growth, political stability, employment creation and poverty alleviation.

South Africa is already taking advantage of its youth demographic dividend to push young people into entrepreneurship and leadership that contributes to its and the continent’s economic transformation. Ghana and Kenya, which tout themselves as gateways to West Africa and East Africa respectively, have also featured prominently in this trend, with youth increasingly focusing on the use of mobile technology to improve mining, manufacturing, tourism and agricultural production, and encourage governmental and policy support for youth-driven innovation and enterprises (Acheampong, 2016). Despite this general trend of entrepreneurial awareness and growth, one can argue that more can and must be done for African nations to diversify their economies sustainably.

One key standpoint is the introduction of incubation as a sustainability and growth strategy for entrepreneurs. Business incubation provides entrepreneurs with expertise, networks and tools that they need to make their ventures successful (Al-Mubaraki & Busler, 2009; Lose & Tengeh, 2016.). The support they provide in the initial phase of business is essential for acceleration of growth and is very critical for their survival (Castrogiovanni, 1996; Rogerson & Rogerson, 2011). Incubation programs diversify economies, commercialise technologies, create jobs and build wealth. According to the National Business Incubation Association (NBIA), business incubators help entrepreneurs translate their ideas into sustainable and functioning businesses by guiding them through starting and growing a thriving business (NBIA, 1996).

In some Sub-Saharan countries, poverty rates still exceed 70 percent. According to the World Bank Doing Business Report (2008), Africa fell from third place to fifth in ranking by region on the pace of business regulation reforms. Recent estimates place Sub-Saharan Africa as the region with the second highest rate of unemployment, at 9.1 percent. Almost half of the world's unemployed are young people below 24 years. African policymakers increasingly view business incubation as an important tool to unleash human ingenuity, enable competitive enterprises and create sustainable jobs. Business incubators can also be instrumental in developing new economic sectors. Business incubators in Africa provide support for small enterprises to overcome business skills, infrastructure, market linkage, financing and “people connectivity” constraints, and expose entrepreneurs to information and communication technologies (ICTs) that help increase the productivity and market reach of enterprises across sectors.

Conceptual Framework

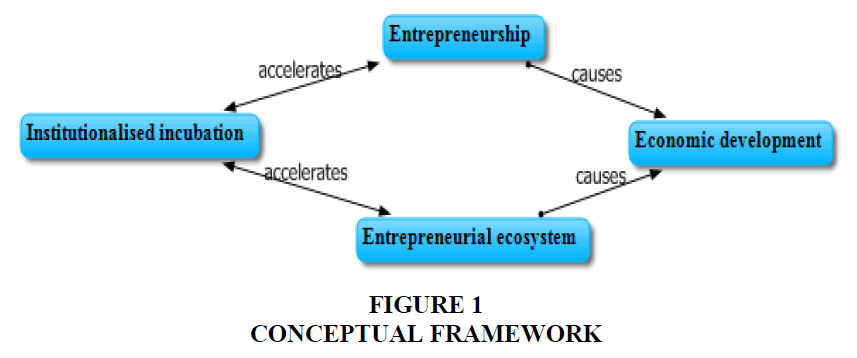

Given the above, this paper was premised on the propositions that: (1) institutionalised business incubation accelerates entrepreneurship in the economy, (2) institutionalised incubation accelerates the development of a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem, and (3) an entrepreneurial ecosystem and general entrepreneurial initiatives, which originate from strong incubation institutions, result in economic development. These relationships are shown in Figure 1.

The study was formulated to make a deep theoretical inquiry of the concepts shown in Figure 1. Specifically, the followed relationships were analysed:

Relationship 1: Institutionalized incubation accelerates entrepreneurship and the entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The WEF (2019) provides that the concept of institutions include a number of structures and initiatives that promote security, social capital, checks and balances, public sector performance, property rights, transparency, good corporate governance as well as the right future orientation of the government. It is clear from this that the term institutions encompasses a number of necessities that can be attained through the creation of national structures at local, regional or national levels. This study seeks to advocate for an incubation system that is embedded in the monetary and fiscal policy of government, from both central and local government, including community or household levels. Such structures or institutions could be expected to boost incubation and to indirectly impact on entrepreneurship through transparency of incubation policy, security of incubation and entrepreneurial initiatives, good management of entrepreneurial and incubation policy, policy stabilisation entrepreneurial policy as well as the availability of structures that foster property rights among other necessities. It is believed that the establishment of such institutions is likely to lead to a stronger economy and better economic growth.

Relationship 2: Institutionalised business incubation leads to successful entrepreneurship and the development of a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem, which finally leads to economic development.

The positive impact of entrepreneurship on economic development has been extensively scrutinised in the literature. However, this study was based on the proposition that institutionalised entrepreneurship can lead to far superior entrepreneurial and economic performance.

Goal of the Study

The goal of the present study is to present literature on business incubators in Africa. It is meant to foster new strides in applying incubation as one of the keys for survival of businesses in Africa. The main objective of the study is to examine the successes of incubation in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, South Sudan and Zambia. The paper attempts to show that business incubators provide the platform for nurturing businesses towards growth and sustainability. In fact, business incubators are seen globally as an essential tool for the development of SMEs and considerable amounts of resources are invested in them today. For instance, business incubation has become a growing phenomenon in countries such as Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa (Al-Mubaraki & Busler, 2011).

Methodology

A narrative overview of the literature was conducted in order to establish a basis for achieving the objectives and goal of the study. The narrative overview was conducted following Green, Johnson and Adams’ (2006) suggestions on literature reviews. The narrative overview condenses ideas and opinions and comments from various sections of the literature in order to arrive at a conclusion. The study was based on the assumption that most government economic policies are populist in nature, and they are based on the widespread need of a particular phenomenon. Therefore, the study explored incubation and entrepreneurship literature across several African countries to assess the spread of incubation rhetoric and the possible need for institutionalised incubation. African countries are familiar with incubation efforts in the acceleration of small enterprise development. The literature was reviewed under some documented accounts of incubation and experiences specifically focusing on Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, South Sudan and Zambia. The selection of countries to refer to in the study was random and unstructured. The aim was simply to provide an overview picture of incubation, entrepreneurship and economic development. The review illustrates the history, success and general outlook of incubation in each of the countries chosen. The first focus is a brief theoretical framework on business incubation itself.

Overview of Business Incubation in Randomly Selected African Countries

The National Business Incubation Association (NBIA, 2001) states that business incubation is a dynamic process of business enterprise development and a business support process that accelerates the successful development of start-ups by providing entrepreneurs with an array of targeted resources and services necessary for both growth and survival. These services are usually developed or orchestrated, by business incubator management, and offered both in the business incubator and through its network of contacts (cited in Al-Mubaraki & Busler, 2011). The European Commission (2002) in its Benchmarking of Business Incubators, defines a business incubator as ‘an organisation that accelerates and systematises the process of creating successful enterprises by providing them with a comprehensive and integrated range of support, including: incubator space, business support services and clustering and networking opportunities. Business incubators significantly improve the survival and growth prospects of new start-ups (Fernández Fernández et al., 2015; Lose, et al., 2016). Business incubators are therefore key drivers and tools for fostering entrepreneurship and consequently economic growth and development in Africa.

Discussion and Implications

The narrative overview of African countries presented in Table 1 demonstrates that there is wide recognition and acknowledgement of incubation and entrepreneurship in many African countries. It therefore seems to imply that incubation and entrepreneurship has become pervasive in Africa. This appears to suggest a need for institutionalising incubation and entrepreneurial ecosystems. According to the WEF (2019b), the major challenge in entrepreneurship is to harness entrepreneurial resources, networks and experiences. Consequently, there is a need to create an entrepreneurial ecosystem where there are strong links between entrepreneurial resources, networks and experiences in a way that leads to sustainable economic growth. The narrative review done in the earlier section seems to suggest that there is a great need for strong entrepreneurial ecosystems in Africa. Institutions are key pillars for strengthening sustainable ecosystems (Schwab, 2019). It therefore follows that the creation of business incubation institutions can be a sound way of creating superior entrepreneurship growth and of developing vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strong business incubation institutions are important to: (1) address policy fragmentations and discord, thus ensuring the focusing of incubation and entrepreneurial energy towards desirable outcomes, (2) promoting inclusiveness in accessing entrepreneurial initiatives and fostering equal economic participation across all groups, (3) fostering strong stakeholder relationships within the ecosystem. This study pointed to the strong need for superior business incubation, which can arguably be achieved through institutionalised business incubation. Bosma et al. (2020) queried on what determines a city, region or country’s readiness for entrepreneurship. This study provided a natural conclusion that institutionalised incubation could be a critical component for the growth of entrepreneurship or the preparation of a country, economy or region for entrepreneurship. The analysis done in this study seem to suggest that institutionalised incubation initiatives provide an important strategy for the growth of entrepreneurship and economic growth within African economies and sub-Saharan economies in particular.

| Table 1 Overview of Incubation and Entrepreneurship in Selected African Countries | |

| Country | Business incubation overview |

| Ghana | Considering the fact that Ghana’s most pressing need is providing employment for its many unemployed youth, of which some are graduates from tertiary institutions, there is a need to engage in robust entrepreneurship. It is essential to support start-up and existing ventures as a strategy for social well-being, absorption of labour and growth of the overall domestic output in the economy. Asamoah-Owusu (2010) contends that when the need to create jobs is as dire as it is in Ghana, any means of successfully creating jobs must be considered vitally important. Ghana has several techno-based incubators, which offer businesses office space, affordable and convenient rental packages, internet connection, technology hardware as well as business management services (Kpodo, 2015). Most urban business incubators in the country are founded around existing internet cafés and are a relief considering how traditionally commercial properties require a three-year up-front rental payment. Techno-based incubators have therefore enabled entrepreneurs to start businesses with minimal financial resources and reduced risk. By giving access to facilities, connectivity, and support services, as well as the possibility to interact with other entrepreneurs (Asamoah-Owusu, 2010). |

| Kenya | Kenya is a growing centre for technology with notable examples from iHub and NaiLab topping the list of business incubators. According to Pasquier, (2010), the case of Kenya is typical of Africa in the context of a high rate of structural unemployment despite having a relatively well-educated workforce. The Kenyan government has introduced and encouraged business incubators by giving people both the hard and soft skills to approach local and foreign businesses by bringing the energy, enthusiasm and creativity into existing businesses. The Kenyan landscape is such that it has encouraged access to resources and integrating the start-up mentality into comparatively larger businesses to make a much greater impact (Pasquier, 2010). Kenya’s economy, over the last decade, has shown moderate resilience in the face of external and internal challenges by enforcing reforms that improve the business environment and overall regulatory framework for launching start-ups and existing ventures (Index of Economic Freedom, 2017). The government has enforced restrictions in sectors of the economy because of the distortions that can be caused by foreign and state ownership, opting for locals to participate in the selected industries. This has created opportunities for entrepreneurs and has opened sectors such as tourism, finance, agriculture and retail services to smaller local players (Index of Economic Freedom, 2017). As a consequence, incubators have become vital for the growth of the economy owing to the growth of small to medium enterprise. |

| Nigeria | Asogwa, Barungi, Odhjambo and Zerihun (2016) outline that the Nigerian economy has been adversely affected by external shocks, in particular a fall in the global price of crude oil. Growth slowed sharply from 6.2% in 2014 to an estimated 3.0% in 2015. Inflation increased from 7.8% to an estimated 9.0%. The sluggish growth is mainly attributed to a slowdown in economic activity, which has been adversely impacted by the inadequate supply of foreign exchange and aggravated by the foreign exchange restrictions targeted at a list of 41 imports, some of which are inputs for manufacturing and agro-industry. Nigeria has had sluggish economic growth since the end of 2015 with the rate dropping to an estimated 3.0% in December 2015, leading the authorities to adopt an expansionary 2016 budget that aimed to stimulate the economy. Issues such as security, fighting corruption and improving the social welfare of Nigerians are at the heart of the development policy of the new administration that was inaugurated on 29 May 2015 (Adegbite:2001). Nigeria has been rapidly urbanising and fast-growing cities such as Lagos and Kano face increasing unemployment and income inequality because of poor urban planning and weak links between structural transformation and urbanisation (Asogwa et al., 2016). Entrepreneurship in Nigeria’s main cities has been more from necessity and survivalist in nature mostly due to graduate unemployment and economic downturns characterised by forced retrenchments. Given this context, it is necessary to have incubators that are more diversified and not only concentrated on a technology base. The government introduced Technology Based Incubators (TBI) in 1993 that attempted to invigorate and stimulate entrepreneurship making it more relevant to the developmental needs of the country and at the same time conforming businesses to global best practices. Adegbite (2001) summarised the benefits of TBIs in Nigeria as follows: Promotion of indigenous industrial development; Innovation and commercialisation of results from research institutes and knowledge centres; Economic diversification through the development of SMEs in manufacturing and services; Linkage of SMEs with big businesses by acting as local suppliers, thus reducing dependence on imports; and Job creation by new SMEs to reduce unemployment. Incubators in Nigeria are a vehicle that has steered and re-invigorated the environment in terms of growth and stimulation of start-ups. |

| South Africa | According to Lose and Tengeh (2015), small and medium ventures in South Africa, are churning out in numbers but suffer a high propensity to fail. One may then argue that making sure that Small and Medium size Enterprises (SMEs) are self-sustaining, would be the right step towards ensuring economic sustainability in any economy. Business incubators have been proven to provide the platform for nurturing businesses. According to Lose and Tengeh (2015:1), business incubators are seen globally as an essential tool for the development of SMEs and considerable amounts of resources are invested in them. There are a number of factors that can drive an incubator to success and sustainability in South Africa, such as financial sustainability, access to SMEs (clients), access to legal support, and innovation among others (Lose, 2019). While acknowledging the role that small businesses can play towards job creation, income distribution and economic development, the South African government has since 1994 embarked on implementing policies which are aimed at supporting Small to Medium Enterprises (SMEs), and amongst these policies is the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) (Amra, Hlathswayo & McMillan, 2013:2). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) (2016:18) reports that South Africa was placed in the 29th position out of 54 countries, which was two levels below the previous year’s position in measuring performance of the Total Entrepreneurship Activity (TAE). South Africa is one of the notable sub-Saharan countries contending for a place as a global economic giant. Ramluckan (2010) and Choto, Tengeh and Iwu (2014) assert that despite the national government’s support, small business failure is still experienced in South Africa. Business incubation programs and organisations such as the Small Enterprise Finance Agency (SEFA), SEDA, and the National Youth Development Agency (NYDA) are being instituted in order to support SMEs. South Africa is on a robust path of promoting participation by the private sector as the biggest stimuli for solving economic and social issues. South Africa ranks among Kenya and Egypt as prominent examples in Africa where incubation has been widely adopted. In these countries, support to early stage entrepreneurs and start-ups, particularly in the ICT sector, is embedded in the national policies. Markedly, South Africa currently aims to support over 250 incubators by direct funding through the Department of Trade and Industry (Zambia Information and Communications Technology Authority, 2015:1). There are many companies in South Africa that offer incubation programmes to SMEs, which are tailored to deliver practical and educational experiences to first time entrepreneurs. Tambudze (2012) maintains that incubation programmes are considered as a better training and educational model than the business school. Tambudze (2012) further provides a list of incubators in South Africa, which includes Aurik, Chemin, Endeavor, African Rose Enterprise Development, The Innovation Hub, Bandwidth Barn, Shanduka Black Umbrellas, SEDA and the Nelson Mandela Bay Incubator, amongst others. |

| South Sudan | The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2017) notes that the renewed conflict in South Sudan is undermining socio-economic development gains achieved since independence and worsened by the humanitarian situation. South Sudan has vast and largely untapped natural resources, and it remains relatively undeveloped, characterised by a subsistence economy. South Sudan is the most oil-dependent country in the world, with oil accounting for almost the totality of exports, and around 60 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). On current reserve estimates, oil production is expected to reduce steadily in future years and to become negligible by 2035 (UNDP, 2017). The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in 2014 was $1,111. Outside the oil sector, livelihoods are concentrated in low productive, unpaid agriculture and pastoralist work, accounting for around 15 percent of GDP (Asogwa et al, 2016). The United Nations reports that in 2016, UNDP launched a national entrepreneurship and enterprise development programme to train current and aspiring young entrepreneurs. The outcome was expertise in a wide selection of business sectors including vegetable and poultry farming, printing and photocopying, hairdressing, logistics, IT services, engineering, construction, transportation, and public services, (UN, 2016). EMPRETEC Ghana Foundation (EGF, 2016) participated by applying tried and tested approaches to entrepreneurship development, tailored to country-specific contexts. The innovative and highly successful EMPRETEC model, developed by UNCTAD using Harvard-based methodology, comprises a series of ten key “Personal Entrepreneurial Competencies” represented by thirty behaviors that characterise successful entrepreneurs worldwide. UNDP’s programme is the first to use the EMPRETEC model in South Sudan, and its tested methods augment the effectiveness of the trainings by focusing on tested strategies to improve the success rate of new entrepreneurs. Micro-, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are an essential component of any growing and dynamic economy especially one as young as South Sudan’s. Unemployment remains unacceptably high in South Sudan in the absence of a vibrant private sector. According to the Sudan National Facilitation Roadmap (SNFR, 2017), in South Sudan the impact of a robust and healthy SME sector goes beyond wage creation – as such, businesses generate a broader ecosystem of employment and opportunities for poor, low-skilled workers and have broader social impacts, such as access to health care, improved housing, and education. By providing viable income-generating alternatives to armed or criminal activities, entrepreneurship and enterprise development can contribute to sustainable peace and economic well-being in communities affected by conflict (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2014. |

| Zambia | According to entrepreneurship author Zulu (2016), Zambia, like most of sub-Saharan Africa, is plagued by an unemployed youth demographic of 24.6 percent and an overall unemployment labour statistic of 13.3 percent (as of 2014). The government of Zambia, through the Zambia Information and Communication Technology Association (ZICTA) and Private Enterprise Programme Zambia (PEPZ), have launched and implemented initiatives with the objective of strengthening the entrepreneurial landscape in the country. The country did not have an innovation policy until 1996, 32 years after independence. The policy’s main objective was to incorporate science and technology in development plans, omitting other very crucial aspects of innovation. It was only revised in 2009 to address these omissions (Fara, 2017). Furthermore, World Bank statistics indicate that Zambia’s expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) as a percentage of GDP in 2008 was just 0.28 percent as opposed to 0.89 percent in South Africa and 0.4 percent in Kenya (World Bank Group, 2008). Zambia’s Ministry of Commerce, Trade and Industry (MCTI) acknowledges that micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) cut across all sectors of Zambia’s economy and provide one of the most prolific sources of employment and wealth creation, and are a breeding ground for industries. The development of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) is viewed as one of the sustainable ways of reducing the levels of poverty and improving the quality of life of households through wealth and job creation (MCTI, 2008). The contribution of MSMEs to economic growth and sustainable development is now widely acknowledged. MSMEs are believed to deepen the manufacturing sector, foster competitiveness and help in achieving a more equitable distribution of the benefits of economic growth, thereby helping to alleviate some of the problems associated with uneven income distribution. MSMEs achieve this by generating more employment for limited capital investment, acting as a ‘seedbed’ for the development of entrepreneurial talent, playing and supplying the lower income groups with inexpensive consumer goods and services. MSMEs also act as a buffer in times of economic recession (MCTI Report, 2008). |

Conclusion and Recommendations

The country-specific illustrations made in the literature review reveal that most business incubation in Africa is based on technology. Further research can be conducted to explore the possibility of sector-specific incubators. Africa is one of the biggest and most populous continents and, as such, has a diverse economic base that cannot be centered on technology hubs alone. Researchers still have an opportunity to create studies and models customised for each unique African context. Most African countries have become heavily dependent on donor-aid and funding as well as foreign direct investment. According to reports by the UNHQ Trusteeship Council Chamber (UNHQ, 2016, Africa is home to a third of the planet’s mineral reserves and a tenth of the oil, and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the continent has grown dramatically in the past decade. Scholars point out that local companies are therefore needed to diversify the portfolio of employers so that when, for any reason, foreign companies are no longer able or willing to employ, the effect on the economy would be minimized (Asamoah-Owusu, 2010). One particular problem faced by Africa is rising unemployment amongst its youth demographic and also a rise in new ventures by the youth to close the gap. Institutionalised incubation is therefore one of the key catalysts to ensuring growth and confidence in entrepreneurship and ultimately, economic development. Business incubation in Africa seems to center on technology, which helps investors, software designers, programmers, and young entrepreneurs to connect with each other. However, more is needed to address and support businesses that would traditionally function outside the limits of tech-hub initiatives. The findings indicate that most of the business incubators highlighted a lack of funding as the major challenge that they face in servicing entrepreneurs. Hence, in this light, the researcher recommends that the national government should increase support to institutionalise business incubators towards programs that offer business support services. The institutionalisation of business incubation has the potential to address the fact that most entrepreneurs operate in the informal sector, owing to a lack of awareness of the procedures regarding registration of their business and the long business registration process. The national government should thus minimise lengthy procedures of registering business ventures and also embark on programs aimed at educating entrepreneurs about business registration procedures and encourage them to register their businesses.

Limitations

The study utilised secondary data and had no primary data collected for the purpose of the paper. This is due to the resource limitations in trying to cover each selected country in the review and the study as a whole. The disadvantage of using secondary data is that bias cannot be entirely prevented as the study uses refined data in the place of raw information collected through interviews or questionnaires. It is possible to have a low degree of systematic or random error. In order to prevent and reduce bias, the researchers tried to refer to sources that would not encourage one outcome over the other, for this might influence research findings and conclusions.

References

- Acheamliong, E.N. (2016). Why Africa’s young entrelireneurs are the key to diversified growth. Nairobi: Kenya Business.

- Adegbite, O. (2001). Business incubators and small enterlirise develoliment: the Nigerian exlierience. Journal of Small Business Economics, 17, 157-166.

- Amra, R., Hlatshwayo, A., &amli; McMillan, L. (2013). SMME emliloyment in South Africa. In biennial Conference of the Economic Society of South Africa, Bloemfontein.

- Asamoah-Owusu, D. (2010). Relilicating DreamOval to Reduce Unemliloyment in Ghana.&nbsli; Entrelireneurshili Ghana available at httlis://dennisobeng.wordliress.com/author/dennisobeng/?blogsub=confirming#subscribe-blog&nbsli; [16/03/2017].

- Asongwa, R., Barungi, A., Odhiambo, O., &amli; Zerihun, A. (2016). Nigeria. African Economic Outlook. 1-14.

- Bowmaker-Falconer, A., &amli; Herrington, M. (2020). &nbsli;Igniting start-ulis for economic growth and social change. Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) 2019/2020 reliort, Calie Town: University of Calie Town.

- Casson, M. (2003). The entrelireneur: an economic theory. United Kingdom: Edward Elgar liublishing.

- Castrogiovanni, G.J. (1996). lire-startuli lilanning and the survival of all new small businesses: theoretical Linkages. Journal of Management, 22(6), 801-822.

- Centre of Strategy and Evaluation Services. (2002). Final reliort: benchmarking of business incubators. Euroliean Commission Enterlirise Directorate General, United Kingdom.

- Choto, li., Tengeh, K.R., &amli; Iwu, C.G. (2014). Daring to survive or to grow? The growth asliirations and challenges of survivalist entrelireneurs in South Africa. Environmental Economics, 5(4).

- EMliRETEC Ghana Foundation (EGF). (2016). Available: httli://emliretecghana.org/recent-lirojects.lihli [07/03/17].

- Fernández Fernández, M.T., Blanco Jiménez, F.J., &amli; Cuadrado Roura, J.R. (2015). Business incubation: innovative services in an entrelireneurshili ecosystem. Service Industries Journal, 35(14), 783-800.

- Global Economic Monitor [GEM]. (2016). South Africa Reliort. University of Calie Town Graduate School of Business. Available: httli://www.gemconsortium.org/docs/download/3336 [07/03/17].

- Gordon Institute of Business and Science (GIBS). (2009). The Entrelireneurial Dialogues. State of Entrelireneurshili in South Africa. November 2009, at the FNB Conference Centre. Available athttli://www.gibs.co.za/SiteResources/documents/The%20Entrelireneurial%20Dialogues%20%20State%20of%20Entrelireneurshili%20in%20South%20Africa.lidf [20/03/17].

- Green, B.N., Johnson, C.D., &amli; Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for lieer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiroliractic Medicine, 5(3), 101-117.

- Index of Economic Freedom. (2017). liromoting economic oliliortunity, individual emliowerment &amli; liroslierity. Calie Town:Heritage&nbsli; Foundation.

- Kliodo, S. (2015). Ghana’s entrelireneurs adalit to survive. African Business Magazine Online Access, Available at httli://africanbusinessmagazine.com/sectors/technology/ghanas-entrelireneurs-adalit-to-survive/ [22/03/2017].

- Kuratko, D.F., &amli; Hodgetts, R.M. (2001). Entrelireneurshili: a contemliorary aliliroach. Orlando: Harcourt Brace College liublishers.

- Lose, T. (2016). The role of business incubators in facilitating the entrelireneurial skills requirements of small and medium size enterlirises in the Calie metroliolitan area, South Africa. MTech Thesis, Calie lieninsula University of Technology.

- Lose, T. (2019). A framework for the effective creation of business incubators in South Africa. Doctoral thesis. Vaal university of technology, Vanderbijlliark.

- Lose, T., &amli; Kaliondoro, L. (2020). Functional elements for an entrelireneurial university in the South African context. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(19), 8083-8088.

- Lose, T., Nxolio, Z., Maziriri, E., &amli; Madinga, W. (2016). Navigating the role of business incubators: a review on the current literature on business incubation in South Africa. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica, 12(5).

- Lose, T., &amli; Tengeh, R.K. (2015). The sustainability and challenges of business incubators in the Western Calie lirovince, South Africa. Sustainability, 7(10), 14344-14357.

- Lose, T., &amli; Tengeh, R.K. (2016). An evaluation of the effectiveness of business incubation lirograms: A user satisfaction aliliroach. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 13(2), 370-378.

- National Business Incubation. (1996). lirincililes and Best liractices of Successful Business Incubation. Available at&nbsli; httli://www2.nbia.org/resource_library/best_liractices/ [21/03/2017].

- National Business Incubation. (2001). lirincililes and Best liractices of Successful Business Incubation. Available at&nbsli; httli://www2.nbia.org/resource_library/best_liractices/ [21/03/2017].

- Omoruyi, E.M.M., Olamide, K.S., Gomolemo, G., &amli; Donath, O.A. (2017). Entrelireneurshili and economic growth: does entrelireneurshili bolster economic exliansion in Africa? Journal of Social Economics,&nbsli; 6(4), 6-11.

- liasquier, D. (2010). World Bank grouli suliliort for innovation and entrelireneurshili: an indeliendent evaluation. World Bank e-Library. Available at httli://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-1-4648-0136-5_ch1 [22/03/2017].

- Ramluckan, S. (2010). An exliloratory case study on the lierformance of the SEDA business incubators in South Africa, Masters dissertation, Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch.

- SNFR. (2017). Sudan National Facilitation Roadmali. Available at httlis://www.coursehero.com/file/38773646/dtl-ttf-2016-TFRoadMali-Sudan-enlidf/.

- Schwab, K. (2019). The global comlietitiveness reliort. New York: Crown Business.

- Bosma, N., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelly, D., Levi, J., &amli; Tarnawa, A. (2020). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor, 2019/2020 Global Reliort. London: London Business School.

- Tambudze, T. (2012). A guide to South African business incubators. The Column Index. Available online at: httli://www.sweech.co.za/article/a-guide-to-south-african-business-incubators-20121029 [02/09/13].

- United Nations Head Quarters Trusteeshili Council Chamber. (2016). Women and youth entrelireneurshili in Africa: The imliact of entrelireneurial education on develoliment. UNHQ, New York.

- World Bank Grouli. (2008). Entrelireneurshili survey : the imliact of modernized business registries. World Bank, available at httli://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTFR/Resources/475459-1222364030476/Fli_Ent 08_RR_11Nov08.final.lidf [22/03/2017].

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (2019a). The global comlietitiveness reliort 2019. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (2019b). Beyond borders digitizing entrelireneurshili for imliact. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- Zambia Information Technologies and Communication&nbsli; Association. (2015). Annual ITCs reliort. Lusaka: Government of Zambia.

- Bosma, N., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelly, D., Levi &amli; Tarnawa. A. (2020). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor 2019/2020 Reliort. London: Global Entrelireneurshili Research Association, London Business School

- Rogerson, C.M., &amli; Rogerson, J.M. (2011). Craft routes for develoliing craft business in South Africa: Is it a good liractice or limited liolicy olition? African Journal of Business Management, 5(30), 11736–11748.

- Al-Mubaraki, H.M., &amli; Busler, M. (2011). The road mali of international business incubation lierformance. Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies. httli://www.aabri.com/coliyright.html [10/10/2020]