Research Article: 2025 Vol: 28 Issue: 2S

Is Entrepreneurship Education for All? A Discussion About Entrepreneurship Education for Refugees

Luciana Padovez Cualheta, Business Administration,Brazil

Citation Information: Padovez, C.L., (2025). Is Entrepreneurship Education For All? A Discussion About Entrepreneurship Education For Refugees. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 28(S2), 1-11.

Abstract

Entrepreneurship education is usually studied in the context of higher education. This paper seeks to contribute to entrepreneurship education theory by promoting a discussion about an often-underrepresented group in entrepreneurship education research - refugees. Based on an entrepreneurship course created for Venezuelan women refugee in Brazil, the author reflects on fundamental aspects needed for entrepreneurship education for refugees to achieve its desired goals. These aspects include the intentional use of technology, the role of peer-to-peer learning, the importance of the relationships between participants, instructors, and mentors. These relationships are viewed not merely as a pedagogical choice for the courses but also to help participants create networks, strengthen their self-esteem, and set more ambitious goals for their businesses. The background of the professor as a strategic choice and the use of seed money as ways of improving engagement were also discussed. Still, the paper reinforces that entrepreneurship education for refugees can have not only economic results, but also social and relational outcomes. It also provides practical guidance for implementing such programs, advocating for public policies that genuinely support refugee entrepreneurship education.

Keywords

Entrepreneurship Education; Entrepreneurship Education For Refugees; Entrepre-neurship by Refugees.

Introduction

Refugees often find it difficult to find jobs, as they may face discrimination and struggle to speak a new language. Many refugees seek entrepreneurship as an alternative to earning income in the country that welcomed them (Desai; Naudé and Stel, 2021; (Zalkat, Barth, and Rashid, 2023). Although staring new businesses is a common practice for refugees, they may find it difficult because they do not have knowledge about the entrepreneurial process, such as identifying opportunities, looking for partners and legal aspects on how to start a business (Jiang et al. 2021; Zalkat, Barth and Rashid, 2023).

Governments and institutions usually offer courses for their citizens who want to start new businesses (OCDE, 2019), but refugees may not have access to those courses and end up in a situation of social vulnerability (Rashid, 2019). This can be worse for women. refugee, who often must reconcile entrepreneurial activities with household chores and childcare (Jose, 2018; OECD, 2019).

The literature on entrepreneurship education has debated whether entrepreneurship can be taught (Fiet, 2000; Kuratko, 2005; Henry and Leitch, 2005; Fayolle and Gailly, 2008; Fayolle, 2013), how it should be taught (Fayolle, 2018; Neck and Corbett, 2018), and its outcomes (Rideout and Gray, 2013; Martin, McNally and Kay, 2013; Nabi et al. 2017), but it is mainly focused on entrepreneurship education in higher education, without emphasis on teaching to other publics in different contexts (McNally and Kay, 2013; Rashid, 2019). Rashid (2019) reviewed 146 articles about entrepreneurship education and found that only 3% of them addressed entrepreneurship education for minorities, with none specifically focused on entrepreneurship education for refugees (Rashid, 2019). Additionally, the educational resources and infrastructure used in entrepreneurship education, such as laboratories, libraries, incubators, and accelerators, can hinder access for minorities and marginalized groups, such as refugees (Bates, Bradford and Seamans, 2018; Rashid, 2019).

Historically, minority entrepreneurs have faced more barriers to start business than their counterparts, such as obtaining appropriate skills, and work experience, accessing financial capital and exploiting market opportunities (Bates, Bradford and Seamans, 2018). This means that they have less access to credit and to mainstream markets. Nevertheless, entrepreneurial initiatives by refugees can significantly contribute to the economic development of host countries, including job creation (Zalkat, Barth and Rashid, 2023; Tariq et al. 2024). In this context, entrepreneurship education represents a possibility to increase the chances of success for these groups (OECD, 2019; Zighan, 2020), especially for women, who face even greater challenges in starting ventures in this context (Sutter, Bruton and Chen, 2019).

Given that refugees face specific challenges when trying to start a business (Embiricos, 2019; Zighan, 2020; Zalkat, Barth and Rashid, 2023), entrepreneurship education should not only address which competences they will require for real-life practice, but it should also be tailored specifically for their needs, rather than just adapting existing training content and facilities (Kyver, Stevffens and Honig, 2022).

Departing from an entrepreneurship course conducted for Venezuelan women refugee in Brazil, it was possible to discuss several aspects of entrepreneurship education for refugees, like the audience specific needs, the use of accessible technology, the use of language as a teaching tool - rather than a barrier - and the influence of the instructor's background, the relationship established among the participants, and the developed networks on the course outcomes. Thus, the article contributes to the theory of entrepreneurship education, specifically discussing entrepreneurship education for refugees, its characteristics and implications (Fasani et al., 2022).

Entrepreneurship by Refugees

According to the United Nation’s High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), refugees are individuals who have escaped war, violence, conflict, or persecution and have crossed an international border to seek refuge in another country (UNHCS, 2018; Desai, Naude and Stel, 2020). Even though this field remains underdeveloped and is frequently examined with immigrant entrepreneurship (Zalkat, Barth, and Rashid, 2023) research on refugees should be a distinct category from other types of migrants, given that they face different circumstances compared to non-forced migrants (Desai, Naude and Stel, 2020).

The difference between migrants and refugees lies primarily in the reason that motivated them to move to a different country (King and Lulle, 2016; Zalkat, Barth, and Rashid, 2023). Unlike other types of immigrants, refugees did not relocate merely for economic reasons but were forced to do so by an external factor, such as war, violence or political instability (Desai; Naude and Stel, 2020). That forced movement can have a significant impact on their livelihoods - after all, they will need to find ways to survive in the new country.

Previous research evidence that, in comparison to the native population, refugees have relatively low employment rates (Kone et al. 2020; Francesco et al. 2022) and fall behind other migrant groups with more social capital within well-established ethnic networks (Tariq et al. 2024). Due to factors such as the absence of formal documentation, lack of professional certification, language barriers, lack of networks, and discrimination, refugees are often unable to fully benefit from employment opportunities in the host country (Bizri, 2017; Bates, Bradford and Seamans, 2018; Tariq et al. 2024).

As a result, on average, refugees exhibit higher rates of entrepreneurship than other types of immigrants or native-born individuals (Hartmann and Philipp, 2022). One reason for this higher entrepreneurship rate among refugees may be that, in general, the countries receiving refugees are unable to provide education, livelihood, and social inclusion opportunities for these groups (Dagar, 2023). Therefore, many refugees are unable to find work in their previous fields and see entrepreneurship as a way to generate income (Wauters and Lambrecht, 2006; Desai, Naude and Stel, 2020; Zalkat, Barth, and Rashid, 2023). Additionally, given that individuals with limited access to formal education often view entrepreneurship as an alternative, refugees who typically lack formal education in host countries may have even less formal knowledge to secure jobs. Therefore, entrepreneurship education can be particularly relevant for this group (Bates, Bradford and Seamans, 2018).

Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurship education relates to personal development, and helps students develop their talents, feel more independent and achieve their dreams. The goals of entrepreneurship education are to transmit techniques and tools that help students increase the chances of new venture creation, survival and success (Fayolle, 2018).

There are different types of entrepreneurship courses or programs, depending on their focus, audience and level. Target groups found in literature are business students, entrepreneurs, SME managers, employees, non-business students in universities, policymakers, investors, unemployed and minority groups (Mwasalwiba, 2011), but most of the research on entrepreneurship education is focused on higher education (Nabi et al. 2017; Rashid, 2019).

Fayolle (2013) points out that research on entrepreneurship education has failed to describe how different target audiences influence goals, contents and methods chosen by educators to best fit each of these audiences. If the goals of entrepreneurship courses are not well described, it is harder to define what students should learn, which competences can be developed and which instructional designs should be chosen (Fayolle, 2013).

Pedagogies vary considerably, and the most frequently used are traditional lectures, active learning, simulations, games, mentoring, guest speakers (Pittaway and Cope, 2007), learning-by-doing and blended learning (Fayolle, 2013). Discussion regarding if approaches should be more hands-on or theoretical are still very common, but it is known that courses should be based on the real world, so students can understand and apply what they learn (Henry, Hill and Leitch, 2005; Neck and Corbett, 2018).

One it comes to refugees, entrepreneurship education should not only consider what they will need for real life practice, but it also has to be customized (Kyver, Steffens and Honig, 2022), as it is hard to achieve good results through education that tries to apply the same methods for all target groups of society (Rashid, 2019). Technology-based entrepreneurship education may be a way to alleviate those challenges, as it enhances the possibilities of personalization, collaboration and engagement, and may also solve the problem of access to specific learning centers by underprivileged groups (Rashid, 2019). That was taken in consideration while developing the course that will be presented in the next section

Method

The Course

A-tua-ação is an entrepreneurship course created for Venezuelan women refugees in Brazil, with the main goal of training them to create and formalize new businesses. The course was also designed to teach Portuguese (all classes, instructions, activities, and materials were in this language), which helped participants to communicate with customers, suppliers and employees and to be more integrated and confident in the host country. It was offered by a non-profit organization in Brazil in 2022, and it was free of charge for the sixteen participants.

The course was eight weeks long, carried out via WhatsApp and taught by a professor who had a Portuguese major and knowledge and experience in entrepreneurship. WhatsApp was chosen as the course platform because it is the most used tool for instant messaging in Brazil (Statista, 2022) and it is common for telephone operators in the country to give free access to this application (Exame, 2018). Thus, women could participate in an online course from anywhere in the country without having to pay for internet use, just by having a smartphone. As the course was online and offered asynchronously, it offered flexible schedules, which allowed students to balance the course with other professional and home activities.

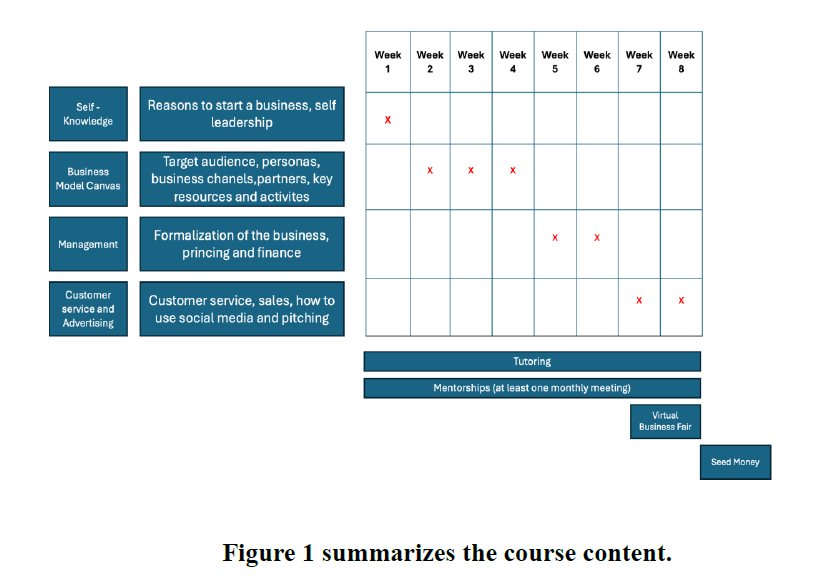

Regarding the course content, it initially addressed self-knowledge content, the reasons to start a business and how to find a business that related to the skills, previous experiences, and routine of the future entrepreneur. Then, business modeling was presented, based on the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). In that stage, participants learned how to define their target audience and design personas, how to develop their business value proposition, how to choose channels for promotion, sales, and delivery, how to create customer relationship strategies, how to identify key partners and how to define the key resources and activities of the business. They also learned how to list the main costs of the business and how to select the best sources of revenue Figure 1.

Participants who completed the course received a seed funding of R$500 ($100) to improve their businesses. All businesses were exposed in a Virtual Business Fair, which took place on an Instagram account. Participants recorded a video of their pitch which were posted on the social network, to promote their business. The three entrepreneurs who had the most “likes” in the publications won prizes (Samwel, 2010).

To ensure the organization of content and networking among the participants, it was decided to create two different groups on WhatsApp: (1) a group with all the participants and organizers of the course, in which only the administrators (instructors and coordination of the course) could send information. Video classes, course materials, activities and general information were sent to this group; (2) another group with all the participants and the professor, in which any member could send messages and materials. In this group, exchanges between participants were encouraged, questions were asked, and comments were made about the activities. All students were encouraged to send their assignments and ask for the opinion of others, thus expanding learning and the connection between them.

The course content was spread over eight weeks. For each content, video classes (which were previously recorded by the professor), and activities related to that theme were sent. It was not a passive course. Students had to practice what they were learning. Those who completed and delivered all activities were entitled to a certificate at the end of the course. Although students were encouraged to share activities with others in the discussion group, all assignments had to be submitted individually to the professor, for recording purposes.

In addition to the professor, students were helped by mentors, to help each participant to improve their business idea, to decide what to do with the financial aid and prepare the pitch to participate in the virtual business fair. These mentorships consisted of meetings, held via video call on WhatsApp, between each student and a self-employed woman with experience in the business area (mentor) who participated in the program on a voluntary basis.

Data collection

In-depth interviews were conducted with each of the sixteen course participants after the end of the course. All ethical procedures were followed and the participants signed an informed consent form to participate in the research. They were asked about what they learned during the course, what changes they were able to identify in terms of their knowledge, skills and attitudes, in addition to pointing out what were the positive and negative aspects of the course. Interviews were conducted at two moments: after the end of the course, in April 2022, and one year later, in April 2023. All of them participated in the 2022 stage. In the 2023 stage, they were invited to collaborate again with the research and six of them accepted to participate. All the interviews were conducted online, through the Google Meet platform, and recorded with the participants' permission. The interviews with students had an average duration of 39 minutes and four seconds, generating an analysis corpus of 139 pages and 61,225 words. Table 1 summarizes the participants' information and the types of businesses created by them.

| Table 1 Participants of the Course. | ||

| Name | Age | Business |

| Alexandra (E1) | 22 | Bakery |

| Andreina (E2) | 33 | Restaurant |

| Eulibet (E3) | 19 | Bakery |

| Francy (E4) | 46 | Restaurant |

| Illiannys (E5) | 24 | Pizzeria |

| Ivete (E6) | 29 | Cestas de café da manhã |

| Jeniffer (E7) | 23 | Cestas de café da manhã |

| Maria Virginia (E8) | 39 | Candy Shop |

| Nairoby (E9) | 26 | Diner |

| Norluisis (E10) | 29 | Diner |

| Stephanie (E11) | 24 | Pastry Shop |

| Viviana (E12) | 31 | Coffee Shop |

| Yanney (E13) | 34 | Cake Shop |

| Yelimar (E14) | 27 | Restaurant |

| Catheryn (E15) | 31 | Restaurant |

| Johaidys (E16) | 24 | Bakery |

It is worth noticing that the participants took the course free of charge and could have felt embarrassed to mention any negative aspects of the course during the interviews, which could bias the results. Even though it is a valid concern, is does not invalidate the research findings, as respondents were explicitly asked about both the negative aspects of the course and suggestions for improvement. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted by the researcher who was not a direct instructor, ensuring a certain level of detachment. This allowed the participants to make suggestions regarding the course and/or the instructor without fear of directly hurting feelings, for example.

The course professor and the mentors were also interviewed, to assess their perception about the course effectiveness and the learning process and results. The sixteen mentors were invited to participate of the research and eight of them accepted the invitation. The professor was interviewed in two moments - while the course was being conceived and after it ended. Interviews with the mentors had an average duration of 24 minutes, generating an analysis corpus of 49 pages and 20,584 words. Interviews with the professor lasted for about one hour each, generating a corpus analysis of 15 pages and 6,182 words.

The author also acted as a silent observer and could access the corpus with all the interactions between the participants and professors in the WhatsApp discussion group. By participating in the groups silently, with the consent of the participants, the researcher was able to observe the interactions between the students and professor. This ensured that the researcher had access to additional information, which would not necessarily be accessible during the interviews, due to memory or perception issues. Screenshots of all the conversations considered relevant for further analysis were taken in Table 2.

| Table 2 Sources of Data | ||

| Source | When? | Number of participants |

| Interview with participants | Round 1: April 2022 Round 2: April 2023 |

Round 1: 16 participants Round 2: 6 participants |

| Interview with mentors | April 2022 | 8 participants |

| Interview with the course professor | Jan- April 2022 | 1 participant |

| Non-participant observation | During the course | Interactions in WhatsApp Groups |

Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was chosen, because it is an accessible and flexible strategy for analysing qualitative data (Braun and Clarke, 2006) and has been used in research on entrepreneurship (Kapoor and Sinha, 2022) and management education (Fang et al. 2023). Thematic analysis aims to identify themes and patterns within the dataset, helping to describe and interpret the data deeply (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The six steps proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006) were followed.

The first stage consisted of familiarization with the data, which involved transcribing the data, performing initial readings and re-readings, and making notes of initial reflections that arose. The second stage was the generation of codes, which are the smallest units of information available in the data, capable of generating significant insights about the phenomenon being studied. Next, in the third stage, the codes were grouped into themes. In the fourth stage, the themes were reviewed to ensure there was no overlap. In the fifth stage, the names of each theme and the narrative of analysis for each were defined. Finally, the sixth stage consisted of writing the analysis, supported by the full transcription of the interviews to substantiate the findings (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

The interviews and the relevant excerpts from WhatsApp group conversations were transcribed into the Word text editor. MAXQDA software was used to group the codes and create themes and sub-themes. Initially, three themes and twenty sub-themes were obtained. A thorough reading of the data ensured that the themes represented a more meaningful grouping of the information obtained in the interviews (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Next, the themes and sub-themes were reviewed by two invited experts – entrepreneurship professors and researchers - to ensure there was no excessive overlap or overly vague themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Two sub-themes were re-grouped to avoid repetition, resulting in eighteen final sub-themes.

Excerpts from the interviews presented in the paper were freely translated into English, while attempting to retain their original meaning and even the informality and casualness of the language. Since the author is fluent in both Portuguese and English, it was considered that the translation did not compromise the fidelity of the presented data.

Results

In common, all the participants of the course decided to pursue entrepreneurship as a way to solve their financial needs. Due to the lack of prior experience in running their own business, the participants engaged in entrepreneurship by starting business somewhat related to their innate vocations or previous skills. For example, E8, E13, and E16 decided to open sweet shops because they already had the habit of making sweets in Venezuela.

The connection with their home country was mentioned as a way of continuing to feel close to their culture, and as a way to stand out in the market by selling products that are less common in Brazil, but very popular in Venezuela. “Arepas are very popular in Venezuela, but hard to find in Brazil, so I realized I could attract customers with this product” (E3). Six of the interviewees stated that entrepreneurship also became a way to balance work and family. This was especially emphasized by those who had children. “I work a lot, but at least I can spend more time with my children and bring them to work if have to (E2).”

The entrepreneurial skills developed in the course can be categorized into three categories: management (financial management, sales, brand identity, marketing, business formalization, managing scarce resources); personal (drive for excellence, perseverance); and relational (customer service and relationships with strategic partners). These skills highlight the effectiveness of the course. It is important to understand characteristics of the course that enabled that outcome.

Flexibility and easy access to the course were cited as advantages by the participants when discussing its characteristics. Since the WhatsApp application is widely used in Brazil, all the students already had it installed on their mobile phones and were familiar with its features. Therefore, it wasn't necessary for them to learn to use a new application, which could have hindered learning due to difficulty or lack of access to the new app's features. Another advantage of using an application that the students were already familiar with was that the instructors' and mentors' time was dedicated to the course content itself, rather than solving technical or operational issues with a new application.

In fact, one of the participants mentioned that, in the past, she had tried to participate in online meetings using a platform she was unfamiliar with and faced problems that led her to not attend the meetings. This is detailed in the words of E3: “[the instructor] asked me to click something to activate the audio and I couldn't. I tried a few times and eventually gave up participating. When I saw that [the current course] would be on WhatsApp, I felt more confident.”

The fact that the course was conducted online, asynchronously, with recorded videos that could be watched at the most convenient time for each participant, allowed for greater engagement with the course. For example, it allowed students to balance the course activities with the business routine, household chores, and childcare. E4 and E12 mentioned that they could listen to the classes using headphones, while performing other activities, which would not be possible if the other course was designed in a different format, such as in-person or through reading alone.

Additionally, the content and exercises of the course were adapted to the needs of the participants. The short content segments allowed each participant to self-pace their participation while ensuring that the delivers and deadlines were clear. Participants were constantly reminded of the deadlines, so they didn't forget to complete each activity. Flexibility and short content were mentioned as advantages of the course: "I would sit down, watch the class and do the exercise trying to remember examples from my daily routine. It didn’t take much of my time and I could do it after work, so it was great" (E5).

It was noted that achievable goals and short exercises were, in a way, responsible for keeping the students disciplined and dedicated to the course. In fact, all participants who started the project met the requirement of completing at least 80% of the activities to earn the certificate of participation and seed capital. According to the instructor, besides the content being delivered in a concise and short manner, another factor that contributed to the positive engagement of the students was the close connection between the instructors and participants and the constant reminders sent via WhatsApp so they wouldn’t forget to summit any of the exercises.

In terms of language, the professor knew it could be a significant barrier for business success, so she worried about that since the conception of the course. “My intention was that the Portuguese language was used as a tool to teach and learn entrepreneurship” (P). Thus, while learning various entrepreneurship concepts and small business management, the students also developed new language skills, so they could speak with their customers, suppliers, and other business partners daily. Hence, students were able to understand jargons, local expressions, and terms specifically used in their type of business, which is a vocabulary that traditional courses might not teach them. According to the instructor, the integration of language and entrepreneurship education optimized the participants' time, as they didn't need to take two separate courses: "they could learn entrepreneurship and Portuguese at once " (P).

The course exercises required the students to also practice Portuguese vocabulary. For example, when they needed to define in a short sentence what their business was, their target audience, and their main benefit, the students weren't just completing a course activity. Instead, they were learning how to present their business in Portuguese and understand the most objective and attractive way to talk about the business in the language used in Brazil. This exercise, although seemingly simple, helped entrepreneurs to acquire new customers and partnerships for their businesses. Similarly, while doing exercises in the sales module of the course, students created phrases in Portuguese that could be used in real conversations with their customers, which helped them to have a richer vocabulary and fluency in negotiations.

Although all the participants already knew how to use WhatsApp before the course, the instructor believes that choosing that technology for the course helped participants to gain fluency, confidence, and practice.

Another advantage of using a low-bandwidth instant messaging application was the possibility of expanding and strengthening the participants' network, even if they were physically distant. This occurred due to the interaction between the students within

Next, the results will be discussed so that the findings from the research can go beyond mere reporting and prescription and indeed contribute to the literature on entrepreneurship education.

Discussion

Entrepreneurship education has been addressed in the literature primarily with a focus on higher education, with little debate on how it should be done for marginalized groups (Rashid, 2019). In one of the few recent articles focused specifically on entrepreneurship education for refugees, Klyver, Stevffens, and Honig (2022) pointed out that Google created a course for Ukrainian refugee women. Although the authors mentioned that the course was conducted online and that the women had access to mentorship, few details were provided, preventing us from knowing whether these initiatives and practices are appropriate, relevant, coherent, and useful (Fayolle, 2013; Martin, McNally and Kay, 2013).

Entrepreneurship plays a crucial role in the lives of refugees, offering them a pathway to economic self-sufficiency and social integration in their host countries (Zalkat, Barth, Rashid, 2023; Tariq et al. 2024). Fostering entrepreneurship among refugees is not only a means of individual empowerment but also a strategic approach to sustainable development and economic growth in host countries (Rashid, 2019; Zalkat, Barth, Rashid, 2023; Tariq et al. 2024). On a philosophical level, entrepreneurship education increases the chances of success for refugee-founded businesses and helps them to get reintegrated, which is why it should be taught—but not in any manner (Klyver, Stevffens, and Honig, 2022). When it comes to entrepreneurship education for refugees, specific issues must be considered.

The fact that the course was conducted via WhatsApp allowed students to ask questions as they arose and share how they were applying the content in real-time, enabling more customized and practice-focused teaching. This approach is recommended by McNally, Honig, and Martin (2018), who emphasized that the theory should be present to inform the content, but the course should have practical applications and be hands-on, especially for students who already own a business.

Using technology allowed the development of skills that the entrepreneurs would genuinely need in their daily lives, such as the Portuguese language, talking to customers, taking good photos, and making social media posts, addressing one of the main challenges faced by minority-founded businesses: access to and knowledge of digital tools. Considering that in Brazil, 146.6 million people use WhatsApp to communicate with each other, and 83% of them use WhatsApp to buy from companies (Statista, 2022), the choice of WhatsApp was more than just a delivery channel for the course but also an extra source of learning. It taught the participants how to use the platform’s features, such as sending photos and audio messages, which helped them to become familiar with the tool that they would most frequently use to serve their customers. Although physically distant, the technology facilitated closer connections between the instructor, mentors, and students, which seemed to contribute to their engagement and learning.

Regarding content and format, in addition to attempting to bridge the gap that often exists between theory and practice (Duval-Coeutil, 2013; Bauman and Lucy, 2021) the course was developed to allow a flow of content without overwhelming the participants. This ensured a flow of ideas, preventing them from getting lost in a lof of infomation, which could happen if they were studying alone.

Byrne, Shantz, and Bullough (2023) found that relationships in courses offered to women victims of violence reinforced self-understanding and acceptance, which was also observed in our research. Besides the relationships among students, the relationship with mentors was crucial for skill development. Mentors played a fundamental role in building self-confidence, influencing how women viewed themselves and their businesses. Hence, in the context of entrepreneurship education for refugees, relationships should be an intentional part of the course design rather than mere additional aspects. Entrepreneurship education for refugees was able to generate more than just a source of income and survival but also considered aspects of well-being, social integration, and holistic development, as proposed by Dagar (2023).

Language should not be sidelined. One of the greatest barriers faced by refugees in adapting to a new country is learning the language of the host country (Bizri, 2017). In A-tua-ação, women learned entrepreneurship while learning Portuguese, which ensured that the language not only ceased to be a barrier but became a bridge for learning. If we want to increase the chances of refugee entrepreneurs having successful businesses, this must be considered when designing new courses.

In the literature on entrepreneurship education, little is said about the background of professors, and there is a call for more research on the topic (Fayolle, 2013; Martin, McNally and Kay, 2013; Nabi et al. 2017). In this research, everything indicates that the characteristics of the instructor made a difference in learning. The fact that she belonged to a marginalized group—a black woman—and owned a small business generated identification and closeness, which seemed to make women feeling more comfortable in sharing their stories and doubts.

Finally, considering that access to financing is more difficult for refugee women and that this can make their businesses generate less revenue (Sutter, Bruton and Chen, 2019), the seed capital may have acted as a catalyst for the future success of their businesses, although further research is necessary to investigate that.

Conclusion

While entrepreneurship education is intended for everyone, one size does not fit them all. Hopefully, the contributions of this paper can help advance both theory and practice when it comes to entrepreneurship education for refugees. This paper contributes to the theory of entrepreneurship education by discussing fundamental aspects of teaching entrepreneurship to a specific and underrepresented minority group in the literature: refugees. In doing so, it addresses several points. The first is how the use of technology can broaden access to an education that is typically restricted to specific higher education groups. The selection of technology should not be made carelessly because, beyond its potential to democratize access to education, it can also serve as an additional learning resource if that technology needs to be used in day-to-day business operations.

Secondly, the paper reflects on how pedagogies and methods should be adapted to participants’ needs and characteristics, to increase their participation and engagement. Thirdly, the relationship between course participants and their instructors and mentors can provide secondary benefits beyond just enhancing learning chances. These relationships can foster a sense of belonging and support, which can be crucial for a group of people who have been forced to abandon their home countries. Additionally, it was noted that in entrepreneurship education for refugees, students can take an active role, incorporating peer-to-peer learning, without disregarding their previous experiences.

The background of the instructors is important in entrepreneurship education, and in the specific case of refugees, it can be even more relevant as it can increase the chance of students identifying themselves with the professor, potentially impacting engagement, relationships, and outcomes. Echoing other authors, the paper highlighted the need for entrepreneurship education to be connected to the real problems that entrepreneurs will face in their businesses, which should be considered in the course design and execution. Lastly, it discussed how funding can serve to combat dropout rates as well as help participants increase their chances of success.

It is also important to emphasize that entrepreneurship education for refugees can have direct implications not only on economic aspects but also on social and relational aspects. Besides the theoretical contributions, the paper offers practical insights by demonstrating how entrepreneurship education for refugees can be implemented, potentially inspiring the creation of similar courses and public policies that genuinely support refugees through entrepreneurship.

References

Bates, T., Bradford, W. D., & Seamans, R. (2018). Minority entrepreneurship in twenty-first century America. Small Business Economics, 50, 415-427.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bauman, A., & Lucy, C. (2021). Enhancing entrepreneurial education: Developing competencies for success. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100293.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Bizri, R. M. (2017). Refugee-entrepreneurship: A social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(9-10), 847-868.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Dagar, P. (2023). Rethinking skills development and entrepreneurship for refugees: The case of five refugee communities in India. International Journal of Educational Development, 101, 102834.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Desai, S., Naudé, W., & Stel, N. (2021). Refugee entrepreneurship: context and directions for future research. Small Business Economics, 56, 933-945.

Embiricos, A. (2020). From refugee to entrepreneur? Challenges to refugee self-reliance in Berlin, Germany. Journal of Refugee Studies, 33(1), 245-267.

Fang, J., Pechenkina, E., & Rayner, G. M. (2023). Undergraduate business students' learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: Insights for remediation of future disruption. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(1), 100763.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fayolle, A. (2018). Personal views on the future of entrepreneurship education. In A research agenda for entrepreneurship education (pp. 127-138). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., & Minale, L. (2022). (The Struggle for) Refugee integration into the labour market: evidence from Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 22(2), 351-393.

Hartmann, C., & Philipp, R. (2022). Lost in space? Refugee entrepreneurship and cultural diversity in spatial contexts. ZFW–Advances in Economic Geography, 66(3), 151-171.

Henry, C., Hill, F., & Leitch, C. (2005). Entrepreneurship education and training: can entrepreneurship be taught? Part I. Education+ training, 47(2), 98-111.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Jiang, Y. D., Straub, C., Klyver, K., & Mauer, R. (2021). Unfolding refugee entrepreneurs' opportunity-production process—Patterns and embeddedness. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(5), 106138.

Jose, S. (2018). Strategic use of digital promotion strategies among female emigrant entrepreneurs in UAE. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 13(6), 1699-1718.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kapoor, U., & Sinha, S. (2022). Transitions and implications of time perspectives: A qualitative study of early-stage entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 18, e00339.

King, R., & Lulle, A. (2016). Research on migration facing realities and maximising opportunities: a policy review. A policy review.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Klyver, K., Steffens, P., & Honig, B. (2022). Psychological factors explaining Ukrainian refugee entrepreneurs’ venture idea novelty. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 18, e00348.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kone, Z. L., Ruiz, I., & Vargas-Silva, C. (2021). Self-employment and reason for migration: are those who migrate for asylum different from other migrants?. Small Business Economics, 56, 947-962.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Kuratko, D. F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: Development, trends, and challenges. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 29(5), 577-597.

Martin, B. C., McNally, J. J., & Kay, M. J. (2013). Examining the formation of human capital in entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of entrepreneurship education outcomes. Journal of business venturing, 28(2), 211-224.

McNally, J. J., Honig, B., & Martin, B. (2018). Does entrepreneurship education develop wisdom? An exploration. A research agenda for entrepreneurship education, 81-102.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of management learning & education, 16(2), 277-299.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Neck, H. M., & Corbett, A. C. (2018). The scholarship of teaching and learning entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1(1), 8-41.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons.

Pittaway, L., & Cope, J. (2007). Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. International small business journal, 25(5), 479-510.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rashid, L. (2019). Entrepreneurship education and sustainable development goals: A literature review and a closer look at fragile states and technology-enabled approaches. Sustainability, 11(19), 5343.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Rideout, E. C., & Gray, D. O. (2013). Does entrepreneurship education really work? A review and methodological critique of the empirical literature on the effects of university‐based entrepreneurship education. Journal of small business management, 51(3), 329-351.

Samwel Mwasalwiba, E. (2010). Entrepreneurship education: a review of its objectives, teaching methods, and impact indicators. Education+ training, 52(1), 20-47.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Sutter, C., Bruton, G. D., & Chen, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. Journal of business venturing, 34(1), 197-214.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Tariq, H., Ali, Y., Sabir, M., Garai-Fodor, M., & Csiszárik-Kocsir, Á. (2024). Barriers to Entrepreneurial Refugees’ Integration into Host Countries: A Case of Afghan Refugees. Sustainability, 16(6), 2281.

Wauters, B., & Lambrecht, J. (2006). Refugee entrepreneurship in Belgium: Potential and practice. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2, 509-525.

Zalkat, G., Barth, H., & Rashid, L. (2024). Refugee entrepreneurship motivations in Sweden and Germany: a comparative case study. Small Business Economics, 63(1), 477-499.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Zighan, S. (2021). Challenges faced by necessity entrepreneurship, the case of Syrian refugees in Jordan. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 15(4), 531-547.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Received: 02-Dec-2024, Manuscript No. AJEE-25-15810; Editor assigned: 03-Dec-2024, PreQC No. AJEE-25-15810(PQ); Reviewed: 10-Dec- 2024, QC No. AJEE-25-15810; Revised: 24-Dec-2024, Manuscript No.AJEE-25-15810(R); Published: 30-Dec-2024