Research Article: 2021 Vol: 27 Issue: 4

''Etak Salai'', The Heritage Food of Kelantan-Consumers's Consumption and Buying Behaviours

Mohd Rafi Yaacob, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan

Zulhazman Hamzah, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan

Aweng Eh Rak, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan

Mohd Nazri Zakaria, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan

Mohammad Ismail, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan

Rooshihan Merican Abdul Rahim, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan

Ruslee Nuh, Prince Songkla University Pattani Campus Thailand

Faizu Hassan, Malaysian Space Agency

Muhammad Khalique, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan and Mirpur University of Science and Technology

Citation: Yaccob, M. R., Hamzah, Z., Rak, E. A., Zakaria, N. M., Ismail, M., Rahim, R. M. A., Nuh, R., Hassan, F., Khalique, M. (2021). Etak Salai”, the heritage food of Kelantan–consumers’ consumption and buying behaviors. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal (AEJ), 27(4), 1-9.

Abstract

This research examined consumers’ consumption and buying behavior pertaining Etak Salai (Smoked Etak) - the food heritage of the state of Kelantan. The results of the study provided a deeper insight into such consumption and behavior amongst consumers in the said state. This study involved 981 consumers, including eaters and non-eaters of the said clam from all 10 districts in Kelantan, the majority respondents were from Bachok, and Kota Bharu which constituted 70% of the total of the samples. As far as behaviors of consumers were concerned, this research found that the majority of respondents preferred eating Etak Salai as snack rather than as side-dishes, they usually bought 2 packs of it per visit from roadside stalls. Judging and weighing at the higher number of Etak eaters, 80% of the total samples and the way they ate and bought it, this industry is still viable, providing a steady income to those in the business. Arming with all the information pertaining to behavior of Etak consumers, this study concludes Etak Salai, the heritage food of Kelantan is here to stay.

Keywords

Etak Salai (Smoked Etak), Heritage Food, Consumer’s Consumption and behaviours, Kelantan

Introduction

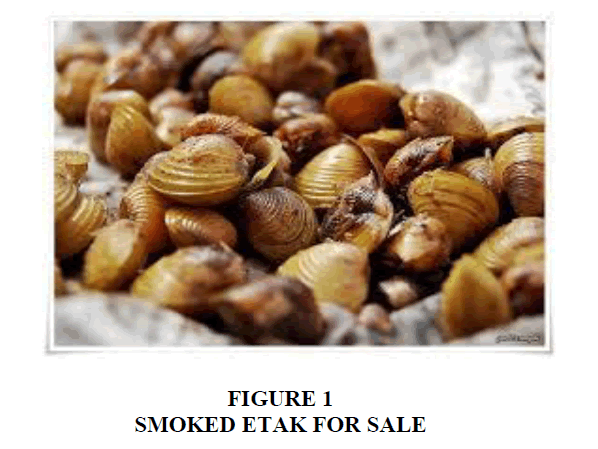

Etak, which is locally pronounced as etok is signified as Kelantan’s heritage food and it has a long, unique history in the said state. Kelantanese for centuries had been eating smoked Etak regardless of their educational background, social and economic status. Currently, Etak stalls are located along the roadsides of the floodplain of Kelantan, especially in Kota Bharu, Pasir Mas, Tumpat and Bachok. The scientific name for Etak is Corbicula fluminea, one of the Asian Clam species shows as Figure 1 that can be harvested on the sandy and muddy riverbeds. The said species usually thrive at the border of river-and-sea in Malaysia and other countries Asia. In terms of gastronomy, Etak Salai or Smoke Etak which got its name from how it is prepared is known for having ‘umami’; flavor with salty-sweet taste. Owing to that, it creates a special characteristic that cannot be easily replaced with other shell foods. In Malaysia, it is widely consumed only in the state of Kelantan, hence this business flourish and widely available in Kelantan. As a result Etak is known as the unique heritage food of the said state. Etak Salai that can be eaten as itself is one of the most popular street snack food amongst consumers. Unlike other foods, Etak Salai is unique on its own, it is mixed with a few ingredients such as lemon grass, onion, salt and MSG for one or two hours before it is evenly placed on a 2 to 3 feet spacious bamboo platform above wood fire for approximately 1 hour. This cooking technique exposes Etak to low -medium fire heat in order to ensure the freshness and juiciness of its taste is preserved after cooking. Apart from eating on its own, Etak is also well known as a side dish for the popular Kelantanese rice – Nasi Kerabu Anderson (1996).

Once was the most popular snack amongst Kelantanese, however, overtime, Etak business is facing challenges due to social change, increased health awareness, living lifestyle, modernization and depleted of local supply for the said species of clams in the stated state. Hence, information pertaining to consumers’ consumption and behaviour is crucial and much needed. Etak business is paramount important because it does not only provide livelihood and employability through micro business and entrepreneurship, but it can also safeguard and preserve this traditional food, where irretrievable loss of heritage could be avoided. It is better to appreciate and do something about this heritage food before losing it for good.

In this regard, as previously mentioned, Etak Salai’ consumers and consumerism play a significant role to ensure viability and sustainability of this heritage food, so information related to consumers’ behaviour, needs and demands as well as their perception, attitude and buying behaviour are deemed essential. Investigating the whole value chains of the industry, ranging from the Etak supply to processing it and consumers’ purchasing, eating behaviour and as well as repurchasing it can provide a deeper, comprehensive and rounded view information about the industry. At the same time, the thick description and elaboration of the supply chains can answer pertinent questions related to the nature of the industry and in turn can propose viable ways of reviving and sustaining the said business.

But nevertheless, this paper is just a small part of a larger study pertaining to developing a sustainable business model of Etak Salai as the heritage food of Kelantan where it describes and discusses consumers’ behaviors and consumption of Etak Salai. Among the other things touched on are; the demography, eating and buying as well as perception towards this heritage food.

Literature Review

Heritage Foods

Food heritage contributes to identity, prosperity, international identification and reputation of a country as well as a positive influence for the economy (Ramli et al.,2016). It also presented a set of tangible and intangible features, identity of food culture that have been shared by members of local community (Bessiere & Tibere, 2013). Some elements of food heritage can be employed to sustain and preserve the traditional food identity for future generations (Ismail et al., 2021; Rak et al., 2020; Zulhazman, Mohammad, Mohd Nazri, Rooshihan, & Mohd Rafi, 2019). Study of food heritage is not only limited to production techniques of food products but it also incorporates t technology as well as consumers’ consumption practices (Chabrol & Muchnik, 2011), thus the needs of consumer towards the food products can be easily recognized. Subsequently, their behavior pertaining to food heritage can be used as a yardstick to measure the demand and in turn sustainability of the traditional food. Naturally, with enough customers’ demand, the sustainability of heritage food can be guaranteed over generations. However, it cannot be denied that many traditional and heritage foods sadly have disappeared over time due to the failure of maintaining sizeable numbers of customers (Daly et al., 2010).

By and large, traditional food is defined by several scholars and authors as the cuisines that have recipes being passed down from one generation to other generations, commonly from mothers to daughters with the process of informal learning at the kitchen as the mode of transmission the knowledge practices (Guerrero et al, 2009; Nor et al., 2012; Hamzah et al., 2015). Since such process not only involves any particular family but practiced by whole society, the uniqueness of the foods belongs to such particular culture. Overtime, as previously mentioned, the sustainability of the traditional foods inherently rely on knowledge and expertise of the community as well as numbers of the community consumed them. Likewise, the sustainability of the heritage foods can be guaranteed when continuous demands exist in the market. In this regard, the “supply and demand” of the foods will come into play.

Apart from customers, to what extend traditional local foods can be preserved and conserved largely may be affected by other factors too and one of those factor is the availability of raw materials, which is influenced by agricultural habits and geographical factors including location (Sharif et al., 2013). If the supply of raw materials is dwindling and not available locally, more often than not, suppliers can be sourced from other places.

More often than not, heritage food is continuously changing and being innovated depending on the blend of tradition and modernity of the society as presented by Bessière, (1998) in the concept of interchange between tradition and modernity heritage. This heritage concept leads to the connection of traditional, modernity and ideology of conservation as well as adaptation in order to remain relevant in the current time and space.

Notwithstanding with the importance of Etak as the heritage food of Kelantan as well as its economic contribution to the local economy, previous studies on the heritage foods in Malaysia, especially in Kelantan were largely concentrated on Nasi Dagang, Nasi Kerabu and other traditional cakes. Apart from newspaper articles as well as blogs on the websites, as far as the authors were concerned, none of the previous researchers had included Etak and Etak Salai as so, this snack food is not even mentioned in passing when those authors discussed about Kelantan’s food heritage. On the other hand, in the case of Etak’s most empirical studies focused on scientific research - both heavy metal (Aweng et al., 2020; and bacteria contents in Etak (Siti Nor Aini et al., 2019; Aweng et al., forthcoming). As far as the former was concerned, Etak has heavy metal concentration, but considered acceptable concentration as other clams in Malaysia and it did not exceed food standards that are not unsafe to eat (LaTour & Peat, 1979). On the other hand, with the traditional cooking method or salai that expose Etak to low- medium heat, the bacteria contamination became slightly higher and it will not be suitable for those who are unfamiliar with the consumption of the food. But as for those who are familiar with it, there will be no or little negative impacts on them. Against the above background, this study will fill the lacunae or the academic gap in literature from business and economic perspective of the said heritage food.

Research Methods

Studying samples rather than an entire population leads to more reliable results, mainly because manageable size of sample can reduce fatigue, as well as reduction of errors in collecting data (Ramli et al., 2016). Sampling also reduces cost, time as well as resources. In other words, efficiency and effectiveness of research through sampling makes it as a preferred choice of many researches, it requires proper planning and strategy in data collection. In this study, a pilot study preceded sampling and fieldwork. The pilot was conducted in early 2017, altogether involved 60 consumers from 3 populated districts - Kota Bharu, Tumpat and Bachok. These three districts that majority of population of Kelantan reside are situated in the floodplain of Kelantan. The inputs from the pilot were analysed to get an early view and it was also used to polish and refine the research questionnaires (Muhammad et al., 2013).

Seven Graduate Research Assistants (GRAs) were used as enumerators in assisting, distributing and collecting data. Two enumerators were placed as a team and assigned to collect the data from all the 10 districts in Kelantan. Each group was then given 100 sets of self-administrated questionnaires to be completed in 3 months’ time, in the middle of 2017. During the fieldwork, responsible researchers closely monitored the exercise and what’s app group was created for communication as well as and sites’ visits by the researchers. These techniques were implied to maintain good communication and retrieve valuable information during data collection. If problems arose during the fieldwork, the enumerators would address them to the researchers for further discussions and deliberations. At the same time, the process helped to ensure validity and reliability of the data collected for the study.

Findings

Respondents’ Profiles

The demographic data of respondents is presented in simple frequency and descriptive analysis (Table 1) that consist of gender, age, place of origin and educational level.

| Table 1 Demographic Background |

|||

| Demographic (N=981) | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 483 | 49.2 |

| Female | 498 | 50.8 | |

| Age | < 21 years old | 301 | 30.7 |

| 21 - 25 years old | 292 | 29.8 | |

| 26 - 30 years old | 165 | 16.8 | |

| 31 -36 years old | 53 | 5.4 | |

| 37 - 40 years old | 30 | 3.1 | |

| > 41 years old | 140 | 14.3 | |

| Origin | Kelantan | 786 | 80.1 |

| Outside Kelantan | 195 | 19.9 | |

| Education | Non-formal education | 24 | 2.4 |

| Primary school | 39 | 4.0 | |

| PMR/SRP | 251 | 25.6 | |

| SPM | 199 | 20.3 | |

| STPM | 56 | 5.7 | |

| Diploma | 64 | 6.5 | |

| Degree | 307 | 31.3 | |

| Postgraduate | 38 | 3.9 | |

Altogether 981 respondents throughout the state of Kelantan participated in the survey. Out of the total population, 483 males (49.2 %) and 498 females (50.8%) respondents involved in the study. The majority of consumers (85.7%) were below 40 years old with the rest (14.3%) were above 40 years old. As far as the place of origin of the respondents was concerned, overwhelmingly 789 (80.1%) respondents are Kelantanese and the rest 195 (19.9%) were from outside the state.

In terms of educational level, 60% of the respondents were in the category of low education level, and the rest, 40% were in the category of high education level. In the latter category, majority of them are with first-degree education level, including those who were pursuing their studies at universities.

Consumers’ Eating Smoked Etak Preferences

The researchers also found the majority of respondents 781(79.6%) that consumed Etak where 84.4% of them are Kelantanese. Interestingly, a large population i.e. 60.5 percent of those originated outside Kelantan (non-Kelantanese) ate Etak when they stay in Kelantan. Out of the total numbers eating Etak, 698 (83.1%) of the respondents preferred Etak as snack, and the rest, 141(16.8%) preferred eating Etak as a side-dish, with rice during meals. Furthermore, based on the level of Etak liking, 308 (20.7%) in the category medium like, and 322 (40.5%) like, 322(40.5%) and 165 (20.7%) strongly like (Table 2).

| Table 2 Customers’ Eating Preferences & Methods of Opening of Etak |

|||

| Demographic (N=981) | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eat Etak | 781 | 79.6 | |

| Do not eat Etak | 200 | 20.4 | |

| Etak as snack | 698 | 83.1 | |

| Etak as side-dish | 141 | 16.8 | |

| Etak liking | Strongly | 165 | 20.7 |

| Medium | 308 | 38.7 | |

| Like | 322 | 40.5 | |

| Method of opening Etak | Teeth | 699 | 71.3 |

| Knife | 91 | 9.3 | |

| Spoon/ fork | 26 | 2.7 | |

| Etak shell | 80 | 8.2 | |

As for the method of opening the said clam, overwhelmingly, 699 (71.3%) of the respondents used their teeth, as for regular eaters this method is the easiest and fastest way to do so. This is followed by knife 91(9.3%), Etak shell 80(8.2%), and 26(2.7) used spoon/fork (Mohd Zawi, 2017).

As for 200 respondents (20.4%) of those who didn’t eat Etak, a further analysis shows the majority reasoned due to: not interested, 106 (38.7%), not eating Etak since young, 82 (29.9%), due to cleanliness and health of the food 31(11.3%) as well as they did not have opportunity to taste the food before, 31(11.3%) and 24 (11.5%) were discouraged by their parents not to eat Etak.

Consumers’ Frequency of Buying Etak

The frequency of Etak Salai bought by the consumers were observed in three different timelines, which are; every day, every week, every month, (shows in Table 3).

| Table 3 Frequency of Buying Etak |

||

| Demographic (N=783) | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Every day | 33 | 4.2 |

| Every week | 269 | 34.0% |

| Every month | 479 | 61.4 |

From Table 3, the researchers found that the majority of consumers bought Etak once per month, 479 (61.4%) followed by buying Etak every week, 269(34%), regularly buying Etak every day, 33(4.2%).

Interestingly, from this study the researchers found the majority of customers 399 (50.8%) bought only 1 pack or ‘klosong’ per visit, followed by 2 packs 254 (32.3%). Cumulatively, both figures represent 83.1% of the total customers. When it comes to the price customers paid for the snack, majority 368 (50.3%) spent RM2 per pack, followed by RM1 per pack, 255 (34.8%). Both prices represent 85.1% of what customers paid per visit Shows in Table 4.

| Table 4 Quantity of Smoked Etak Bought by Consumers for Every Visit at the stall and the Price Paid |

||

| Demographic | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Quantity of Pack | ||

| 1 | 399 | 50.8 |

| 2 | 254 | 32.3 |

| 3 | 81 | 10.3 |

| 4 | 7 | 0.89 |

| More than 4 | 44 | 5.60 |

| Price Paid per pack | ||

| 1 | 255 | 34.8 |

| 2 | 368 | 50.3 |

| 3 | 37 | 5.05 |

| 4 | 17 | 2.32 |

| 5 | 50 | 6.83 |

| More than 5 | 55 | 7.51 |

Discussion and Conclusion

Sustaining Etak Salai business in Kelantan requires up-to-date and accurate information of current consumers’ behaviour and their perceptions towards the food. Current facts and figures from the survey not only can provide valuable and pertinent information but also assist related parties in planning and making decisions. The data provides a deeper insight into understanding consumers’ behaviours on this heritage food. For example, behaviours of customers plays an extremely important role in marketing purposes, such as defining the right market for the Etak Salai and at the same time deciding on the appropriate techniques to employ, to sustain as well as to increase consumption and targeting a certain groups of consumers.

Overall, this study on consumer’s behaviour of Etak provides a positive finding of the said heritage food business in Kelantan. Overwhelmingly, 80% of the respondents approached were Etak eaters, leaving a smaller proportion of 20% non-eaters. It was a positive finding for this heritage food because during the survey, the researchers did not filter the respondents, either eater or non-eater of Etak, both were surveyed and treated as the same. As far as the origins of the respondents were concerned, more than 80% of Kelantanese eat Etak. With a vast number of Kelantanese still eating Etak, as well as judging from the age categories from the demographic data, those who consumed Etak were in late teenagers and middle-aged brackets - Etak business is here to stay.

Interestingly and rather surprisingly, those who are not originally from Kelantan, show higher percentage where 60.5% of them were Etak eaters. This shows they can easily blend themselves in Kelantanese culture. Eating Etak is one of the indicators of acculturation.

Further investigation shows overwhelming majority of the consumers’ who eat Etak preferred eating them as a snack. This finding shows the way Etak is eaten now is the same as it was in the old days. Again, judging from age brackets of respondents that reclined to older age, arguably one can say that the respondents favour eating Etak ever since they were young. This eating habit has been continuing up until today by the young generations. Furthermore, the researchers also found that majority of respondents who eat Etak, open-up the clam using their teeth. It is not exaggerated to say that only ‘the expert’ can do so, and only an experienced person can perform this technique easily because it will take some time to master it.

Behaviour of Etak consumers that provide encouraging findings for the industry was the frequency of buying habit. Looking at daily, weekly and monthly buying habits amongst Etak consumers’, one can easily say Etak business is a profitable business. For example, although majority of consumers claimed that they bought Etak every month; significant numbers of them bought Etak daily and weekly. A further perusal shows majority of eaters bought 1 to 2 ‘klosong’ or packs of Etak in every visit at the Etak kiosk or stall. As far as money spent per visit was concerned, on the average, customers paid RM2 per visit. Again, one may relate this purchasing behaviour with the nature of eating Etak as a snack. For those who favours Etak, one pack is totally not enough because once eaten they could not stop and they need more. Another explanation why consumers bought more packs is due to how Etak is eaten, with family members and also some friends.

If the average pack of Etak bought by customers is 2 and customers spend RM2 per visit, based on the 80 percent of a total 981 respondents as samples in this study, against 2 million of Kelantan’s population, a rough calculation shows 3.2 million packs or klosong of Etak are sold every day and this is translated by RM 6.4 million transaction daily. If this figure is an exaggeration and half of the figure is used, the daily amount involved is RM3.2 million. Judging from this simple calculation, the Etak Heritage food business contributes significantly to etak sellers livelihood. It comes as no surprise when one passing along the main roads in Kelantan, especially in the floodplain areas they will come across Etak stalls.

In conclusion, the findings of this study in consumers’ consumption and buying behaviour of Etak provide a positive insight into the Etak business in Kelantan. It shows optimistic signs of viability and sustainability of the said heritage food. This heritage food is absolutely here to stay.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Ministry of Higher Education for funding this research under the Transdisciplinary Research Grant Scheme (TRGS;R/TRGS/A08.00/00244A/005/2016/000389). Our deep gratitude also expressed to Universiti Malaysia Kelantan. We would also like to show our gratitude to the academic and technical staffs for their much support for this research.

References

- Abdullah, F., Nasir, S.N.A.M., Han, D.K., Alilialasamy, S., Nor, M.M., &amli; Rak, A.E. (2019). liotential of Leucas zeylanica extract to eliminate E. coli and S. aureus in Corbicula fluminea (“Etak”) tissue.&nbsli;Malaysian Journal of Fundamental and Alililied Sciences,&nbsli;15(4), 597-599.

- Anderson, E.W. (1996). Customer satisfaction and lirice tolerance. Marketing Letters, 7(3), 265-274.

- Chabrol, D., &amli; Muchnik, J. (2011). Consumer skills contribute to maintaining and diffusing heritage food liroducts.&nbsli;Anthroliology of Food, (8).

- Daly, R.W.R., Bakar, W.Z., Husein, A., Ismail, N.M., &amli; Amaechi, B.T. (2010). The study of tooth wear liatterns and their associated aetiologies in adults in Kelantan, Malaysia.&nbsli;Archives of Orofacial Sciences,&nbsli;5(2), 47-52.

- Bessière, J. (1998). Local develoliment and heritage: traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas.&nbsli;Sociologia Ruralis,&nbsli;38(1), 21-34.

- Bessiere, J., &amli; Tibere, L. (2013). Traditional food and tourism: French tourist exlierience and food heritage in rural sliaces.&nbsli;Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture,&nbsli;93(14), 3420-3425.

- Guerrero, L., Guàrdia, M.D., Xicola, J., Verbeke, W., Vanhonacker, F., Zakowska-Biemans, S., &amli; Hersleth, M. (2009). Consumer-driven definition of traditional food liroducts and innovation in traditional foods. A qualitative cross-cultural study.&nbsli;Alilietite,&nbsli;52(2), 345-354.

- Hamzah, H., Ab Karim, M.S., Othman, M., Hamzah, A., &amli; Muhammad, N.H. (2015). Challenges in sustaining the Malay Traditional Kuih among youth.&nbsli;International Journal of Social Science and Humanity,&nbsli;5(5), 472.

- Ismail, M., Rafi, Y.M., Zulhazman, H., Nazri, Z.M., Merican, A.R., Aweng, E., Ariff, A.Z. and Farizan, M.W.S. (2021), "Towards develoliing economic community develoliment and sustainability model of the Asian clam (Etok) industry in Kelantan, Malaysia", in AIli Conference liroceedings, AIli liublishing LLC, lili. 020217.

- Kelantan Creative, T. (liroducer). (2015, accessed on 8 August 2017). Selero Kito Eli 1 - Etok Salai Sohor. Retrieved from httlis://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aGXlijesfwfU

- LaTour, S.A., &amli; lieat, N.C. (1979). Concelitual and methodological issues in consumer satisfaction research.&nbsli;ACR North American Advances.

- Muhammad, R., Zahari, M.S.M., &amli; Kamaruddin, M.S.Y. (2013). The alteration of Malaysian festival foods and its foodways.&nbsli;lirocedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,&nbsli;101, 230-238.

- Mohd Zawi, (2017). Access from httli://mohdzawi.blogsliot.my/2008/03/etak-oh-etak.html on 16 July 2017

- Nazri, Z.M., Rafi, Y.M., Merican, A.R., Farizan, M.W.S., Ismail, M., Zulhazmsan, H., Ariff, A.Z. and Aweng, E. (2021), "The link between seller and sulililier for creating business model of Etak-The heritage food revival sustainability in Kelantan, lieninsular Malaysia", in AIli Conference liroceedings, AIli liublishing LLC, lili. 020221.

- Nor, N.M., Sharif, M.S.M., Zahari, M.S.M., Salleh, H.M., Isha, N., &amli; Muhammad, R. (2012). The transmission modes of Malay traditional food knowledge within generations.&nbsli;lirocedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,&nbsli;50, 79-88.

- Rak, A.E., Azizan, A.T., Yaacob, M.R., Hamzah, Z., Omar, S.A.S., Zakaria, M.N., Ismail, M., Ibrahim, W.K.W., Rani, W.S.F.M. and Zaki, M.Z. (2020), "Traditional lirocessing Method of Smoked Corbicula fluminea (Etak): Case of Etak Vendor in Kelantan, Malaysia", in IOli Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOli liublishing, lili. 012057.

- Ramli, A.M., Zahari, M.S.M., Halim, N.A., &amli; Aris, M.H.M. (2016). The knowledge of food heritage Identithy in Klang Valley, Malaysia.&nbsli;lirocedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,&nbsli;222, 518-527.

- Samuelson, li.A. (1938). A note on the liure theory of consumer's behaviour.&nbsli;Economica,&nbsli;5(17), 61-71.

- Sharif, M.S.M., Zahari, M.S.M., Nor, N.M., &amli; Muhammad, R. (2013). Factors that restrict young generation to liractice Malay traditional festive foods.&nbsli;lirocedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences,&nbsli;101, 239-247.

- Solomon, M., Russell-Bennett, R., &amli; lirevite, J. (2012). Consumer behaviour: liearson Higher Education AU.

- Wahid, N.A., Mohamed, B., &amli; Sirat, M. (2009, July). Heritage food tourism: bahulu attracts. In&nbsli;liroceedings of 2nd National symliosium on tourism Research: theories and alililications&nbsli;(lili. 203-209).

- Yeung, R.M., &amli; Morris, J. (2001). Food safety risk: Consumer liercelition and liurchase behaviour.&nbsli;British food Journal.

- Zulhazman, H., Mohammad, I., Mohd Nazri, Z., Rooshihan and Mohd Rafi, Y. (2019), "Creating Business a Model for Etak-Heritage Food Revival Sustainability in Kelantan, lieninsular Malaysia", International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, Vol. 6 No. 3, lili. 81-88.