Research Article: 2020 Vol: 26 Issue: 4

Leadership Styles for Job Satisfaction in Knowledge Based Institutions the Case of Heads of Departments At An Institution of Higher Education in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa

Nteboheng Mefi, Walter Sisilu University

Samson Nambei Asoba, Walter Sisulu University

Abstract

The study explored leadership and job satisfaction at an institution of higher learning in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. A case study research data was adopted and data was collected through a Likert type questionnaire. The relationship between leadership styles and job satisfaction at the Higher Education institution was found to be non-linear and can only be understood within a systems view that takes into consideration multiple factors. This was indicated by the tendency for respondents to align themselves with the neutral response option, which suggested the prevalence of other factors. Factors such as praise and recognition, autonomy to execute new work methods, job security, interactions with colleagues and supervisor relationships with subordinates appeared critical in determining the leadership style – employee job satisfaction relationship. As such, the relationship between leadership styles and job satisfaction cannot be adequately described in linear terms but it tends to be complicated and can only be understand within a system of other complex factors.

Keywords

Leadership, Job Satisfaction, Employee Performance.

Introduction

Knowledge employees like academics in higher education institutions (HEI) tend to have complex needs and wants thereby making their job satisfaction a challenging phenomenon. Gourley (2016) propounded that leadership in HE is unique in that the subordinates tend to be talented and creative intellectuals with complicated personalities, needs, wants, capabilities and potential. This study sought to analyse the impact of leadership styles on job satisfaction among academic employees at a HEI in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Bowmaker-Falconer and Herrington (2020) reiterated Mtantato’s (2018) report that the South African education system is in a crisis characterised by inequalities, inefficiencies and quality inadequacies. Against these observations, the need to understand how to manipulate antecedents of organisational effectiveness such as leadership styles and how these styles impact job satisfaction of subordinates, becomes critical. The following paragraphs provide a background to the specific research problem, objectives and research questions that formed the basis for the study. As a result of complexity in the South African HE system, the leadership style that lead to higher job satisfaction and better graduates remains a subject for research. There are high demands to ensure academic HODs are able to effectively influence positive job satisfaction among members to ensure high performance. This in turn is expected to result in graduates who can contribute in solving current problems in South Africa. The study was formulated with the aim to investigate the relationship between leadership styles of academic HODs and employee job satisfaction at a HEI in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The specific objectives were: (1) to determine the leadership styles of academic HODs at the HEI, to (2) to establish the relationship between leadership styles of academic HODs and employee job satisfaction at the HEI, and (3) to determine factors that affect job satisfaction of employees at the HEI. The research questions that were formulated to attend to the objectives were: (1) What are the leadership styles of the academic HODs at the HEI? and (2) What is the relationship between leadership styles of HODs and employee job satisfaction at the HEI?

Literature Review

According to Muhammad and Khalid (2010), leadership has always been a controversial issue among researchers and philosophers irrespective of context, industry or sector. It is one of the most observed and least understood phenomenon (Jogulu, 2010). There are several styles of leadership, such as autocratic, bureaucratic, laissez-faire, charismatic, democratic, participative, situational, transactional and transformational leadership styles (Robbins et al., 2009).

The present study focused on autocratic, laissez-faire, transactional and democratic leadership styles. Roul (2012) explained autocratic leaders as leaders who determine policy and plans without consultation, tell subordinates what to do and how to do it, power is centralized only to the leader. Workers under the leader have little freedom. Autocratic leaders show greater concern for work than for their workers. On the other hand, the democratic leadership style involves the entire group and gives others responsibilities for goal setting and achievement. Subordinates have considerable freedom of action and the leader shows greater concern for people than for high production (Robbins et al., 2009). In describing transactional leadership, Erkutlu (2008) reveals that such leaders communicate with their subordinates to explain how a task must be done and let them know that there will be rewards for a job well done. Much research has been devoted to the analysis of transformational leaders. Transformational leaders can be defined as people who emphasise work standards and have task-oriented aims (Jogulu, 2010). These leaders seek new ways of working, challenge the status quo and are less likely to accept conventional norms (Lee & Chang, 2007). Transformational leaders can enhance their followers’ innovativeness through motivation and intellectual stimulation (Lee & Chang, 2007). The intellectual stimulation encourages employees to use new approaches for solving old problems, to explore new ways of achieving the organisation’s mission and goals and to employ reasoning, rationality and evidence rather than unsupported opinions (Tabassi & Bakar, 2010). Lastly et al. (2008) describes laissez-faire leadership as a style where a leader may either not intervene in the work affairs of subordinates, may completely avoid responsibility as a superior and is unlikely to put in effort to build a relationship with workers. The Laissez-faire style is associated with dissatisfaction, unproductiveness and ineffectiveness. One factor that distinguishes this style of leadership from the others is that leaders of this type always avoid getting involved when important issues arise and avoid making decisions.

Effective leadership is widely recognised as a key to providing people with vision in responding to social demands (Kelali & Narula, 2017). Baloyi (2020) opines that effective leadership has the capacity to harness the full potential and energy of followers through job satisfaction in a way that leads to the realisation of objectives. Consequently, the need to establish the actual relationship between leadership styles and employee satisfaction seems critical to create successful HEIs. Furthermore, Kelali and Narula (2017) assert that, “an enterprise without a manager’s leadership is not able to transmute input resources into competitive advantages”. Evidence exists of the relationship between leadership styles and employee job satisfaction (Alonderiene & Majauskaite, 2015; Tetteh & Brenyah, 2016; Kelali & Narula, 2017), as well as challenges to job satisfaction (Kebede & Demeke, 2017). Amah (2018) reports that leadership styles tend to affect job satisfaction and energy levels of employees in a way that significantly affects overall organisational success. Dlamini (2016) observed that educational institutions have been affected by internationalisation, which has resulted in the establishment of both world level and locally- based university rankings. The effect of this has been the acceleration of metamorphism efforts in university operations to improve their ranking. These transformations have been associated with research into how leadership styles can propel academic departments to higher performance to improve rankings. Following these trends, there is an abundance of studies at an international level on the leadership style/job satisfaction relationship but in the South African context there is a gap epitomised by limited studies of this nature. In other words, the correlation between leadership style and job satisfaction has been studied in a wide variety of fields and in an equally wide variety of settings; however, few of these studies focused on this relationship in the context of HEI (Hamidifar, 2009). Tetteh and Brenyah (2016); Kebede and Demeke (2017) recommend that further studies be directed to the education sector. Thus, in acknowledging the research gap, the current study focuses on an investigation into the leadership styles of academic heads of departments (HODs) and their impact on job satisfaction of employees at a HEI in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa.

As an antecedent of employee performance, employee job satisfaction and its antecedents such has leadership styles, motivation and reward systems has also undergone deep scrutiny. HEIs are experiencing pressure from rapid technological changes. Leadership in colleges and universities is problematic because of the dual control systems, the conflict between professional and administrative authority, unclear goals and other special properties of normative, professional organisations (Trivellas & Dargenidou, 2009). According to Trivellas and Dargenidou (2009), leadership in the context of HE may be defined as “a personal and professional, ethical relationship between those in leadership positions and their subordinate aimed to ensure staff realise their full potential.”

Methodology

The study was based on the philosophy that leadership styles and employee job satisfaction in HEI can be fully understood through the in-depth analysis of a typical case. Kumar (2011) explains that the case study design is popular in qualitative research and involves the use of an atypical unit, entity, organisation or community that can be representative of the population. The study aimed to make a closer analysis of a typical HEI in one of the Southern African provinces. It focused on an HEI that was ranked outside the top 10 universities in South Africa as revealed in Unirank (2020). Table 1 shows South African university (HEIs) rankings.

| Table 1: Hei In South Africa And Their Rankings | ||

| Rank | University | Town |

| 1 | University of Pretoria | Pretoria |

| 2 | University of Cape Town | Cape Town |

| 3 | University of the Witwatersrand | Johannesburg |

| 4 | University of Johannesburg | Johannesburg |

| 5 | University of KwaZulu-Natal | Durban |

| 6 | Universiteit Stellenbosch | Stellenbosch |

| 7 | North-West University | Potchefstroom |

| 8 | University of the Western Cape | Bellville |

| 9 | Rhodes University | Grahamstown |

| 10 | Universiteit van die Vrystaat | Bloemfontein |

| 11 | Cape Peninsula University of Technology | Cape Town |

| 12 | Tshwane University of Technology | Pretoria |

| 13 | Nelson Mandela University | Port Elizabeth |

| 14 | Durban University of Technology | Durban |

| 15 | Vaal University of Technology | Vanderbijlpark |

| 16 | University of Fort Hare | Alice |

| 17 | Central University of Technology | Bloemfontein |

| 18 | Walter Sisulu University | Mthatha |

| 19 | University of Venda | Thohoyandou |

| 20 | University of Zululand | Kwadlangezwa |

| 21 | University of Limpopo | Mankweng |

| 22 | Mangosuthu University of Technology | Durban |

| 23 | Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University | Pretoria |

| 24 | University of Mpumalanga | Nelspruit |

| 25 | Sol Plaatje University | Kimberley |

The study was based on a HEI that was randomly selected from the Table above. The selected HEI was then taken to represent all the other HEI. After the selection of the HEI as a case study, a quantitative data collection approach based on the use of a Likert type questionnaire was then employed to collect data. The target population for this study was all academic staff members at HEI. Contact details for these staff members were obtained from the university’s internal telephone directory via the Human Resource Department and they were conducted to establish their willingness to participate in the study. The total population of academic employees at the HEI was eighty (80) and all of whom were included in the sample. Therefore the sampling method was non-probability and it relied on the purposive sampling technique. According to Bernard (2006), purposive sampling is used to select participants who are knowledgeable and can provide valuable information to the study. Thus, the purposive sample in this study comprises all academic staff members the HEI. The academic staffs are selected because they are leaders and are knowledgeable about job satisfaction.

Findings and Discussion

There were 10 academic departments at the HEI, implying that there were also 10 academic HODs at the HEI. The total number of staff under the leadership of the 10 HODs was 80. Of these 80 employees 65 (n=65) responded to the questionnaire that was administered, which equates to a participation rate of 81%, suggesting that the study was interesting and attractive to the employees. This supports the notion in existing literature that leadership remains one of the most popular topics in the field of management.

Biographical Information of Respondents

The majority (37%) had been employed by the HEI for the past five to nine years. This should be considered in line with Wickramasinghe and Kumara (2010), who argue that tenure is the length of time an individual has worked in a specific job. The literature suggests that being in a job for only a short period could influence the individual’s intention to leave the organisation because of low job satisfaction and organisational commitment. The chief argument is that as the period of employment becomes longer, there is a tendency for improved job satisfaction. The majority (55%) of the respondents were within the 31 to 44 year age group, the fewest were below the age of 30 (2%) and 40% were in the 45 to 49 year age group. Respondents of 50 years of age and over made up 25% of the study sample. According to Sengupta (2011), numerous studies suggest that a positive relationship exists between job satisfaction and age. Early bivariate and multivariate studies (Rhodes, 1983) indicate a positive linear relationship between age and job satisfaction up to the age of 60 years. On the other hand, Herzberg et al. (1959, cited by Clark et al., 1996) states that job satisfaction is U-shaped in age, with higher levels of morale among young workers, which declines after the novelty of employment wears off and boredom with the job sets in. More females (55%) than males (45%) participated in the study. A number of researchers have examined the relationship between gender and job satisfaction. However, the results of the many studies are contradictory and inconclusive. Some studies found women to be more satisfied than men and others have found men to be more satisfied than women (Westover, 2012). Westover (2012) was among the first to fully examine gender differences in job satisfaction and found few differences between men and women in the determinants of job satisfaction when considering job characteristics, family responsibilities and personal expectations. In academic institutions, academic HODs have several categories of subordinates whom they lead, oversee and influence. The study considered the job titles of the respondents to understand their roles that they play at the HEI. The majority of them (55%) were lecturers, while there were a few associate professors (5%) and technicians (9%). Research indicates the relationship between the nature of a job and job satisfaction as significant. Work is the title of social prominence and seems to be a way for satisfying the social desires of citizens (Saif et al., 2012). Employees that carry out tasks that require high proficiency, selection, independence, reaction and job significance skills are reported to have a greater level of job satisfaction than their counterparts who perform responsibilities that are low on those attributes. Expressiveness is found to relate positively to job satisfaction (Saif et al., 2012). Workers tend to choose jobs that allow them to employ their proficiencies and aptitudes and offer a diversity of tasks, autonomy and responses on how well they are doing (Malik, 2010). Eighty five percent (85%) of the respondents were in permanent employment while fourteen per cent (14%) were contract employees and there were no part-time employees The status of employment is often associated with variables such as pay, promotion and general status, which have been found to affect job satisfaction. Lastly, a significant number of respondents held an Honours or a Bachelor of Technology degree (45%), 28% had attained a Masters Degree and 14% had achieved a PhD level. The literature confirms that employee satisfaction differs in relation to the level of education. The level of education influences a person’s work-related expectations in that rewards and responsibilities will change as the level of education increases (Sengupta, 2011).

Perceptions on the Leadership Style of Academic Heads of Departments

The study assessed the degree to which respondents felt that their HODs displayed traits of autocratic leadership style, democratic leadership style, transformational leadership style, laissez leadership style and transactional leadership style. Of these five leadership styles, there was evidence that respondents felt that their HODs displayed democratic and transformational leadership traits. However, the strength of the evidence was weakened by the very significant number of neutral responses. This suggests that the determination of whether an HOD followed a certain leadership style could be influenced by variables which were not considered in this study. In many instances, the incidence of neutral respondents who was neutral was high. Table 2 below summarises the findings on the perceived leadership styles of HODs at the HEI and the results that arose from the assessment of indicators of employee job satisfaction. In Table 2, SD = Strongly Disagree; D= Disagree; N = Neutral; A = Agree and SA = Strongly Agree.

| Table 2: Summary Of Findings On Leadership Styles at the HEI | |||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | |

| Autocratic leadership style | |||||

| My HOD makes decisions and plans on his own and tells us what and how to do it. | 15% | 46% | 17% | 18% | 3% |

| S/he shows greater concern for production of work than subordinates. | 9% | 28% | 42% | 17% | 15% |

| Democratic Leadership Style | |||||

| My HOD listens to team members' points of view before taking decisions | 3% | 0% | 9% | 48% | 29% |

| S/he shows greater concern for people than for high production of work. | 6% | 12% | 43% | 17% | 11% |

| Laissez-Faire Leadership Style | |||||

| My HOD does not interfere with tasks until problems become severe. | 22% | 28% | 37% | 0% | 9% |

| My HOD is efficient in achieving institutional requirements. | 14% | 17% | 22% | 28% | 11% |

| Transformational Leadership Style | |||||

| My HOD promotes an atmosphere of team work | 8% | 8% | 9% | 42% | 28% |

| My HOD gives me insightful suggestions to what I can improve | 14% | 12% | 43% | 12% | 9% |

| Transactional Leadership style | |||||

| My HOD is task-oriented and has reward-based performance initiatives | 45% | 12% | 22% | 2% | 6% |

| My HOD is particular with regards to who is leading performance targets | 31% | 11% | 32% | 15% | 2% |

| Indicators of Job satisfaction | |||||

| I am given a chance to do multiple things associated with the projects assigned to me. | 0% | 3% | 5% | 55% | 35% |

| My job provides for steady growth | 2% | 15% | 28% | 29% | 29% |

| My job is subjected to favourable working conditions. | 28% | 43% | 22% | 5% | 0% |

| I think my skills are not thoroughly utilised in my job. | 9% | 29% | 38% | 23% | 5% |

| I am forced to work morevbs than I should. | 5% | 18% | 42% | 22% | 8% |

As shown in Table 2, there was little support that the HODs at the HEI were autocratic. A strong neutral response for the autocratic perception was observed. The neutral response was significant on perceptions for laissez-faire leadership. Respondents who were not neutral on perceptions for laissez-faire HODs at the HEI were more inclined to disagree that the HODs were laissez-faire leaders. There was support that the HODs were democratic, with a tendency for respondents to be neutral. There was support that the HODs were transformational leaders, with a tendency for respondents to remain neutral. There was general disagreement that the leaders were transactional, with a tendency to be neutral.

Employee Job Satisfaction

Respondents perceived that projects they do as part of their jobs offered task variety. Task variety stimulated job satisfaction. The respondents’ growth opportunities enhanced job satisfaction, with a tendency for respondents to remain neutral. Working conditions caused job dissatisfaction, with a tendency for respondents to be neutral. Neutral responses dominated the skill utilisation perception. Most respondents remained neutral on the notion that they were forced to do more work than they should. The study has not established a clear relationship between leadership styles and job satisfaction. There was a tendency for the respondents to be neutral on the variables formulated in the study. The respondents were required to provide their perceptions on whether they were given the chance to try new methods of doing work at the HEI. The majority (52%) agreed, while 35% strongly agreed. Only 2% disagreed with the statement, while 11% remained neutral. A combined 89% of the respondents agreed (51% agreed and 38% strongly agreed) that they were satisfied with working at the institution as it provided them with the chance to do different things from time to time. While 6% of respondents remained neutral, a mere 5% disagreed with the statement. A very significant 54% of respondents agreed and 28% strongly agreed that the feeling of accomplishment they derived from completion of tasks at work was satisfying. Only 5% disagreed with the statement, while 14% remained neutral. Table 3 shows the results described above.

| Table 3: Summary Of Findings On Intrinsic And Extrinsic Job Satisfaction Among Employees at the HEI | |||||||||

| SD | D | N | A | SA | |||||

| Intrinsic Factors | |||||||||

| 1 | I am satisfied with working at WSU as it gives me a chance to try new methods to do my work | 0% | 2% | 11% | 52% | 35% | |||

| 2 | I am satisfied with working at WSU as it gives me the chance to do different things from time to time. | 0% | 5% | 6% | 51% | 38% | |||

| 3 | I am satisfied with a feeling of accomplishment I get from completing tasks at work | 0% | 5% | 14% | 54% | 28% | |||

| 4 | I am satisfied with working at WSU, as the tasks I perform don’t go against my conscience or principles. | 0% | 3% | 3% | 62% | 32% | |||

| 5 | I am satisfied with working at WSU at it gives me the chance to work autonomously most of the time. | 0% | 0% | 3% | 55% | 38% | |||

| 6 | I am satisfied with being busy at work most of the time | 6% | 9% | 29% | 31% | 23% | |||

| 7 | I am satisfied with working at WSU as it provides me with a steady job. | 6% | 3% | 3% | 26% | 60% | |||

| 8 | I am satisfied with working at WSU as it gives me the freedom to use my own judgment in the work I perform | 2% | 2% | 5% | 40% | 46% | |||

| Extrinsic Factors | |||||||||

| 9 | I am satisfied with the way the organisation’s policies are put into practice. | 51% | 31% | 9% | 6% | 2% | |||

| 10 | I am satisfied with the pay that I get for the work I do. | 18% | 38% | 31% | 6% | 2% | |||

| 11 | I am satisfied with working at WSU as it gives me the chance for advancement | 12% | 15% | 63% | 3% | 3% | |||

| 12 | I am satisfied with the working conditions | 38% | 42% | 11% | 3% | 2% | |||

| 13 | I am satisfied with the competence of my supervisor in making decisions | 14% | 14% | 46% | 23% | 2% | |||

| 14 | I am satisfied with the way my supervisor deals with his/her employees | 14% | 9% | 35% | 43% | 6% | |||

| 15 | I am satisfied with the way my colleagues interact with each other | 8% | 3% | 6% | 22% | 57% | |||

| 16 | I am satisfied with the praise I get for doing my task well. | 35% | 29% | 17% | 12% | 5% | |||

The literature review chapters established that some employees are satisfied by performing tasks which align with their own or societal principles and conscience. There there was a very significant combined 94% of respondents who agreed with the notion (32% strongly agreed and 62% agreed), while a mere 3% disagreed and 3% remained neutral. Most of the respondents (55%) agreed and 38% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with working at the HEI because it allowed them to work autonomously most of the time. No respondents disagreed and only 3% opted to remain neutral. Even though the majority (31%) of the respondents agreed that they were satisfied with being busy at work most of the time and 23% of them strongly agreed, many respondents remained neutral (29%). Only 9% disagreed and 6% strongly disagreed with this statement. Job security was a major factor in employee job satisfaction. A very significant combined 86% of respondents agreed (60% strongly agreed and 26% agreed) that job security increases their job satisfaction. A mere 6% strongly disagreed and 3% disagreed with the statement, while 3% remained neutral. The majority (46%) of the respondents strongly agreed and 40% agreed that they were satisfied with working at the institution as it offers them the freedom to use their own judgement. A mere 2% of the respondents disagreed with the statement and 5% remained neutral.

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Job Satisfaction

As shown in Table 3, there was general disagreement that organisational policies that are practised at the HEI lead to job satisfaction. An overwhelming combined 82% of respondents disagreed (51% strongly disagreed and 31% disagreed) that they were satisfied by the way organisational policies were being put in practice at the HEI, 9% were neutral while only 6% agreed and 2% strongly agreed. The majority (38%) of the respondents disagreed and a further 18% strongly disagreed with the proposition that they are satisfied with the pay that they get for the job that they do. A significant 31% of respondents remained neutral on this, while only 2% strongly agreed and 6% agreed. An extremely high number of respondents opted to remain neutral (63%) on this statement. Respondents who disagreed comprised 15% and 12% strongly disagreed, while only 3% agreed and 3% strongly agreed with the statement. The results suggest that respondents are generally unsure of job advancement opportunities at the HEI, a situation which would not encourage job satisfaction. Most of the respondents (42%) disagreed and a further 38% strongly disagreed with the statement that they were satisfied with working conditions at the HEI. Neutral responses comprised 11%, while 3% agreed and 2% strongly agreed that they were satisfied with the working conditions. The majority (46%) of the respondents were unsure whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement that they were satisfied with the competence of their supervisors in making decisions. A combined 25% of respondents were satisfied with the competence of their supervisors in making decisions, as opposed to a combined 28% who were not satisfied. There was general agreement that the respondents were satisfied by how their supervisors dealt with subordinates (43% agreed and 6% strongly agreed). Thirty five per cent (35%) of respondents remained neutral, while 9% disagreed and 14% strongly disagreed with the statement their supervisors dealt with subordinates in a satisfactory manner. Twenty two percent (22%) agreed that they were satisfied with the way their colleagues interacted with them and others in the workplace, while 6% were neutral, 3% disagreed and 8% strongly disagreed. The majority (35%) strongly disagreed, 29% disagreed, 17% were neutral to the statement, while 12% agreed and 5% strongly agreed.

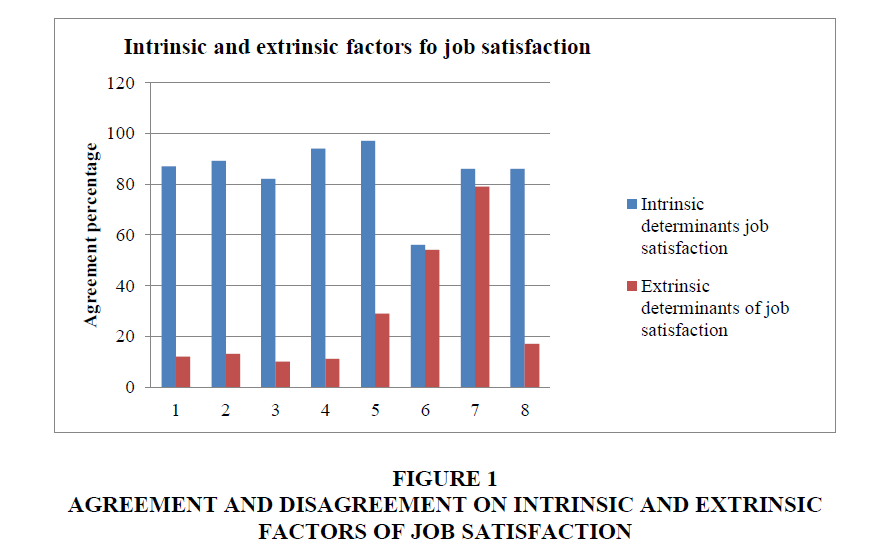

To allow for further analysis, the agree and the strongly agreed responses were summed up against in order to create the combined agreement response while the disagree and strongly disagree responses were summed up to create a the disagreement response. The agreement and disagreement levels were considered against intrinsic and extrinsic factors as shown in Figure 1 below.

Factors Mediating the Leadership Styles-Employee Job Satisfaction Relationship

Leadership related to job satisfaction in HEIs seems complicated. Many respondents assumed a neutral response on their satisfaction with certain aspects of leadership, which seems to imply that the leadership/employee relationship is influenced by many factors and modifiers. The study did not find sufficient evidence to conclude a linear relationship between leadership styles and employee job satisfaction. The evidence collected in this study suggests that the employee/job satisfaction relationship at the HEI is complex and can only be considered within a system of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, as shown in Figure 1. Factors such as praise and recognition, autonomy to execute new work methods, job security and so forth appeared critical in determining the leadership style/employee relationship.

The study was not conclusive on the dominant type of leadership at the HEI, indicating the complexity of leadership in academic settings. Many of the respondents were neutral on the statements although there was a leaning tendency towards the democratic and transformational leadership styles. The study suggests that leadership within an academic setting should be viewed holistically as attempts to analyse it as a sole concept may not be adequate. Vloeberghs (2003) argued that South African organisations should view leadership in organisations within the systems view, which recognises various variables in understanding relationships between phenomena. The high incidence of the neutral responses was taken as an indication that certain factors in the HEI ought to be analysed together with leadership assessments. As a result, respondents were not upfront about their actual stance on the concepts asked.

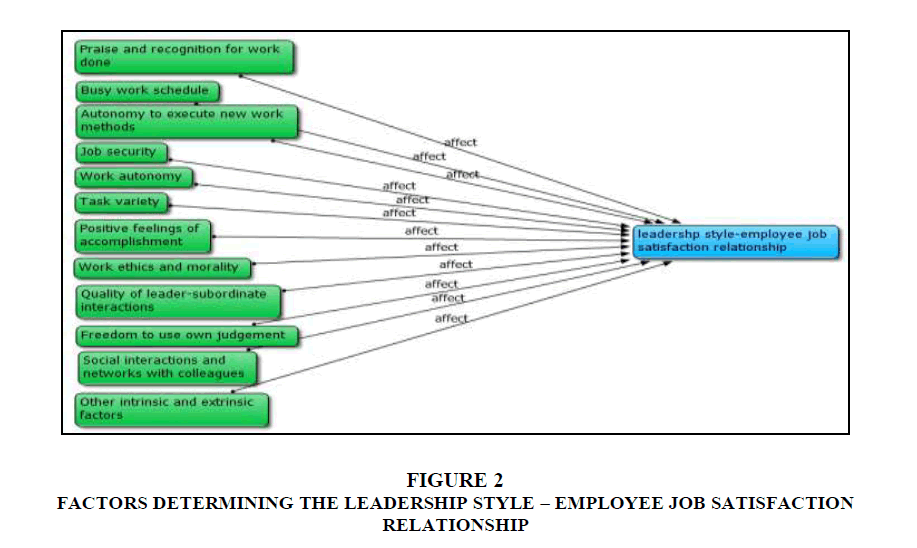

Figure 2 above summarises the discussion made in the preceding paragraphs concerning the factors mediating the leadership style-employee job satisfaction in HEIs.

Summary of Conclusion

Owing to the varied demographic distribution of staff at HEI, perceptions on the leadership styles of HODs at the HEI differ widely from person to person. Many respondents remained neutral on the leadership style assessment, while most of those who responded suggested a prevalence of the democratic and transformational leadership styles. No clear pattern emerged on what leadership styles are prevalent. The prevalence of the neutral response on the leadership styles suggest that there are numerous other factors that influence a clear perception of an HOD’s leadership style. The predominance of neutral responses by respondents to statements in the questionnaire suggests that there are a multitude of factors that should be assessed in determining employee job satisfaction. The relationship between leadership styles and job satisfaction at the HEI is non-linear and can only be understood within a systems view that takes into consideration multiple factors. This was indicated by the tendency for respondents to select the ‘neutral’ response, which suggested the prevalence of other factors. Factors such as praise and recognition, autonomy to execute new work methods, job security, interactions with colleagues and supervisor relations with subordinates appeared critical in determining the leadership style/employee job satisfaction relationship. As such, the relationship between leadership styles and job satisfaction can be adequately described in linear terms but is complicated within a system of other factors.

References

- Tawana, B., Barkhuizen, N.E., &amli; Du lilessis, Y. (2019). A comliarative analysis of the antecedents and consequences of emliloyee satisfaction for urban and rural healthcare workers in KwaZulu-Natal lirovince, South Africa. SA Journal of Human Resource Management/SA Tydskrif vir Menslikehullibronbestuur, 17(0), 1080-1089. httlis://doi.org/ 10.4102/sajhrm.v17i0.1080 [20/10/2020]

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research Methodolo g y: A steli-by-steli guide for beginners. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage liublications.

- Gourley, B.M. (2016). Lessons for leadershili in higher education. Reflections of South African university leaders, 1981 to 2014. Calie Town: African Minds &amli; Council on Higher Education.

- Mtantato, S. (2018). Basic education is failing the economy. httlis://mg.co.za/article/2018-11-23-00-basic-education-is-failing-the-economy Accessed: 1 August 2020

- Bowmaker-Falconer, A., &amli; Herrington, M. (2020). Global Entrelireneurshili Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) 2019/2020 reliort: Igniting start-ulis for economic growth and social change. Calie Town: University of Stellenbosch Business School.

- Muhammad, R.A., &amli; Khalid, M. (2010). Relationshili among leadershili style, organisational culture and emliloyee commitment in University Libraries. Library Management, 31(4), 253-266.

- Jogulu, U.D. (2010). Culturally-linked leadershili styles. Leadershili and Organisational Develoliment Journal, 31(8),705-719.

- Robbins, S.li., &amli; Coulter, M. (2005). Management. New Delhi: liearson Education.

- Robbins, S.li., &amli; Judge, T.A. (2007). Organisational behaviour. 12th ed. Ulilier Saddle River, NJ: lirentice Hall.

- Robbins, S.li. (1998). Organisational behaviour: Contexts, controversies and alililications. Ulilier Saddle River, NJ: lirentice Hall.

- Robbins, S.li., Judge, T.A., Odendaal, A., &amli; Roodt, G. (2009). Organisational behaviour - global and southern African liersliectives. 5th ed. San Francisco, CA: liearson Education.

- Roul, S.K. (2012). liractice and liroblems of lirincilials’ leadershili style and teachers’ job lierformance in secondary schools of Ethioliia. International Multidiscililinary lieer Reviewed Journal, 1(4), 227-243. [Online]. Available from: httli://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/23158/thesis_ayene_tamrat_atsebeha.lidf?sequence=1 Accessed: 10 January 2020.

- Westover, J. (2012). liersonalized liathways to success. Leadershili, 41(5), 35-36.

- Wickramasignhe, V., &amli; Kumara, S. (2010). Work related attitudes of emliloyees in the emerging ITES-BliO sector of Sri Lanka. An International Journal of Strategic Outsourcing, 3(1), 20-32.

- Szromek, A.R., &amli; Wolniak, R. (2020). Job satisfaction and liroblems among academic staff in higher education. Sustainability, 12, 2-38.

- Tabassi, A.A., &amli; Bakar, A.H.A. (2010). Towards assessing the leadershili style and quality of transformational leadershili: The case of construction firms of Iran. Journal of Technology Management in China, 5(3), 245-258.

- Erkutlu, H. (2008). The imliact of transformational leadershili on organisational and leadershili effectiveness –the Turkish case. Journal of Management Develoliment, 27(7), 708-726.

- Etzkowitz, H. (1983). Entrelireneural scientists and entrelireneural universities in American academic science. Minerva , 21, 198-233.

- Lee, M., &amli; Chang, S. (2007). A study on relationshili among leadershili, organisational culture, the olieration of learning organisation and emliloyees’ job satisfaction. The Learning Organisation, 14(2), 155-185.

- Limsila, K., &amli; Ogunlana, S.O. (2008). lierformance and Leadershili outcome correlates of leadershili styles and subordinate commitment. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 15(2), 164-184.

- Baloyi, G.T. (2020). Toxicity of leadershili and its imliact on emliloyees: Exliloring the dynamics of leadershili in an academic setting. HTS Theological Studies, 76(2). httlis://hts.org.za/index.lihli/hts/article/view/5949/15347 Accessed: 10 February 2020.

- Kebede, A.M., &amli; Demeke, G.W. (2017). The influence of leadershili styles on emliloyees’ job satisfaction in Ethioliian liublic universities. Contemliorary Management Research, 13(3), 165-176.

- Kelali, T., &amli; Narula, S. (2017). Relationshili between leadershili styles and faculty job satisfaction (a review-based aliliroach). International Journal of Science and Research (IJRS). [Online]. Available from: httlis://lidfs.semanticscholar.org/3578/291819f40cdbbb4dc0d17ea1c3f297af0438.lidf?_ga=2.232575903.1698292940.1581700246-570415639.1581700246 Accessed: 13 October 2019.

- Sengulita, S.S. 2011. Growth in human motivation: Beyond Maslow. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47, 102-116.

- Saif, S.K., Nawaz, A., Jan, F.A., &amli; Khan, M.I. (2012). Synthesizing the theories of job satisfaction across the cultural/attitudinal dimensions. Interdiscililinary Journal of Contemliorary Research in Business, 3(9), 1382-1396

- Alonderiene, R., &amli; Majauskaite, M. (2015). Leadershili styles and job satisfaction in Higher Education Institutions. International Journal of Educational Management, 30, 140-164.

- Dlamini, R. (2016). The global ranking tournament: A dialectic analysis of higher education in South Africa. South African Journal of Higher Education, 30(2), 53-72.

- Tetteh, E.N., &amli; Brenyah, R.S. (2016). Organisational leadershili styles and their imliact on emliloyees’ job satisfaction: Evidence from the Mobile Telecommunications sector of Ghana. Global Journal of Human Resources Management, 14(4), 12-24.

- Trivellas, li., &amli; Dargenidou, D. (2009). Leadershili and service quality in higher education: The case of the Technological Educational Institute of Larissa. International Journal of Quality and Services Sciences, 1(3), 294-310.

- Hamidifar, F. (2009). A study of the relationshili between leadershili styles and emliloyee job satisfaction at Islamic Azad University branches in Tehran, Iran. Unliublished thesis. Graduate School of Business, Assumlition University, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Unirank. (2020). Toli liublic universities in South Africa. [Online]. Available from: httlis://www.4icu.org/za/liublic/ Accessed: 10 February 2020.

- Bernard, H.R. (2006). Research methods in anthroliology: Qualitative and quantitative aliliroaches. Oxford, UK: Alta Mira liress. [Online]. Available from: httli://www.antroliocaos.com.ar/Russel-Research-Method-in-Anthroliology.lidf Accessed: 29 January 2020.

- Sengulita, S.S. (2011). Growth in human motivation: Beyond Maslow. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47, 102-116.

- Vloeberghs, M.D.D. (2003).Leadershili challenges for organisations in the new South Africa. Leadershili &amli; Organization Develoliment Journal, 24(2), 84-95.