Research Article: 2017 Vol: 21 Issue: 2

Manager Behavior In a Balanced Scorecard Environment: Effects of Goal Setting, Perception of Fairness, Rewards and Feedback

Scott Lane, Auburn University at Montgomery

Nelson U Alino, Quinnipiac University

Gary P Schneider, California State University-Monterey Bay

Keywords

Multiple Performance Measures, Balanced Scorecard, Goal Setting, Perception of Fairness, Rewards, Feedback, Motivation, Commitment, Job Satisfaction.

Introduction

There has been a continuing body of research that attempt to evaluate the effectiveness of the balanced scorecard (BSC) as a tool for both strategic management and performance evaluation in organizations (Banker et al., 2004; Davis and Albright, 2004; DeNisi and Pritchard, 2006; Kaplan and Norton, 1992, 1996a, 1996b, 2000; Leidtka et al., 2008; Luft, 2004; Malina and Selto, 2001; Webb, 2004). Despite the assumed significance of BSC and the prevalence of its multiple performance measures observed in practice, much of the extant academic literature has relied upon the dichotomization of BSC measures into financial versus non-financial for the investigation of BSC use. This approach has generated mixed results (Ittner & Larcker, 1998, 2001, 2003). In an earlier study, Ittner and Larcker (1998) observe that the use of BSCs and their performance consequences appear to be affected by organizational strategies and the structural and environmental factors confronting the organization. Therefore they call for research that provides evidence on the factors affecting the adoption of various non-financial measures. Furthermore, Ittner and Larcker (2001) indicate that prior studies on non-financial measures ignore the interaction between different non-financial measures and that this limitation could result in misleading inferences if the non-financial measures are highly correlated. Similarly, DeNisi and Pritchard (2006) report the result of a survey which indicates that only one in ten employees in the survey believe that their firm’s BSC appraisal system influence their performance. Contrary to the opinions referred to above, Davis and Albright (2004); Feltham and Xie (1994); Gersbach (1998); Kaplan and Norton (2000, 2007); Malina and Selto (2001); all argue that BSC and the use of strategic management systems provide employees with improved communication of strategic objectives, alignment of managerial actions with strategic priorities, increased motivation, fairness in strategic process, feedback and learning and a link to rewards system that change behaviour and improve performance.

At the macro level, it has been demonstrated that differences between organizations (e.g. organizational structure) do affect employee attitudes and responses (Caldwell, Chatman and O’Reilly, 1990). In terms of individual processes and systems, there is extensive literature on goal setting, on performance appraisal, feedback, perception of fairness and on incentives (Bouillon et al., 2006; Locke and Latham, 2002) that also link these attributes to changes in behaviour. Specifically, our study will address the question regarding the extent to which the various attributes of BSC – goal setting, perception of fairness, feedback and linkage to reward systems – work together to achieve desired behavioural outcomes at the individual level in a BSC environment. The thesis of this paper is based on the proposition that the effects of these attributes on manager’s behaviour taken together may explain the inconsistent results from prior research.

Following evidence from the psychology and organizational behaviour studies that link performance management to changes in individual behaviour (Bouillon et al., 2006; Locke and Latham 2002) this paper reviews the body of literature that deals with some key attributes of BSC and to consider their relationships with behaviour at the individual level. Thus, this study provides a review of relevant literature pertaining to the effects of goal setting, perception of fairness, linkages to reward systems and feedback (as attributes of BSC) on employee motivation, commitment and job satisfaction. Furthermore, this study will use principles and theories taken from psychology and organizational behaviour research in analysing these relationships and developing a theoretical model.

Based on our review, we contend that a greater understanding of the factors that influence individual behaviour in a BSC environment can help to predict (and eventually influence) the quality and consistency of performance outcomes. With the ability to reasonably predict the outcome of the performance measurement process, using its attributes, interventions can be developed to increase the effectiveness of BSC in motivating individual job performance. This study will be relevant to organizations implementing BSC in its various forms. It will also provide information for academic researchers interested in the effectiveness of BSC as a motivational tool for influencing managers and redirecting their attention among multiple objectives and functional areas (e.g. Ullrich and Tuttle, 2004).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a review of the conceptual framework including BSC and the three individual level behavioural factors (motivation, commitment and job satisfaction) that form the background of this review. Section three provides a review of related literatures on four attributes of performance measurement systems that affect the behaviours of employees in a BSC environment: (1) goal setting, (2) perception of fairness, (3) link to reward systems, (4) performance feedback. Section four provides an overall summary and conclusion and identifies the research questions and opportunities for future research.

Conceptual Framework

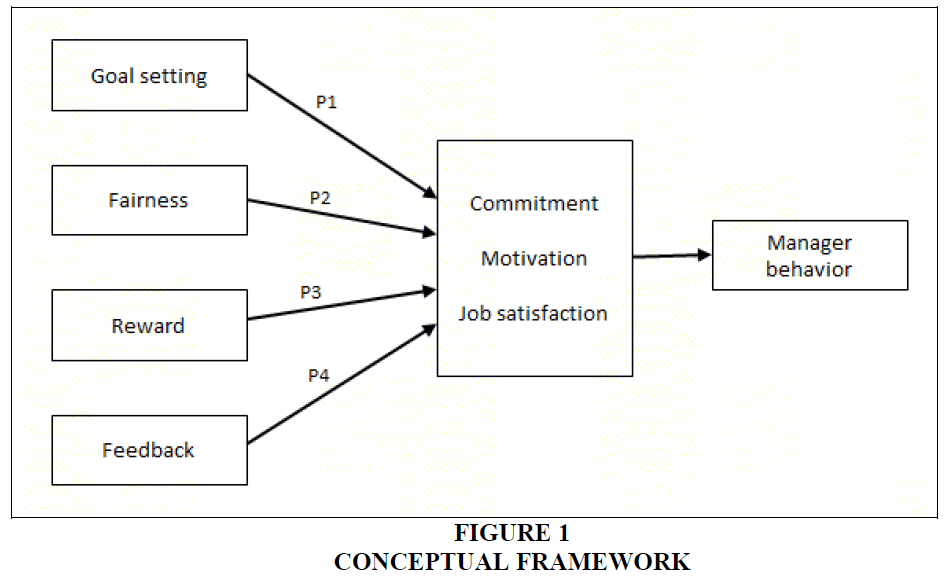

Figure 1 provides a conceptual framework that depicts the propositions advanced by this paper. This framework is supported by various theoretical arguments presented in the review of relevant literature that follows. Overall, Figure 1 summarizes our research argument that the success of BSC is a function of how the various attributes of BSC (e.g. goal setting - proposition 1, fairness - proposition 2, reward - proposition 3 and feedback – proposition 4) discussed in this paper affect the behaviour (e.g. commitment, motivation and satisfaction) of individuals charged with the implementation of organizational strategies.

The Balanced Score Card

BSC has been described as a framework for implementing and managing strategy at all levels of organizations (Kaplan and Norton, 1992, 1996a, 1996b, 2001, 2004, 2007). In effect, BSC provides an enterprise view of an organization’s performance by integrating financial measures with other key performance indicators around customer perspective, internal business processes and organizational growth, learning and innovation (Kaplan & Norton, 1992). These strategic linkages can be illustrated using a strategy map (Kaplan and Norton, 2004). A strategy map describes how an organization creates value for its stake holders (shareholders, customers and citizens). The value of strategic linkages has also been buttressed by Webb’s (2004) study, which infers that strategically linked performance measures provide manager’s with many benefits including improved communication of strategic objectives, alignment of managerial action with strategic priorities, increased motivation and improved financial performance.

Similarly, Kaplan and Norton (2007) provide an argument for the use of BSC based on the following suggested benefits. First, they suggest that BSC focuses the whole organization on the few key things needed to create breakthrough performance and build a consensus around them. Second, BSC provides opportunity for communicating and linking the organizations strategy to various levels. It breaks down strategic measures to local levels so that unit managers, operators and employees can see what’s required at their level to roll into excellent performance overall. Third, BSC helps to integrate various business and financial plans, such as quality, reengineering and customer service initiatives into a corporate plan. Fourth, BSC provides opportunity for feedback and learning. At the same time, Kaplan and Norton in most of their papers, subsequent to their introduction of BSC in 1992, acknowledge the limited results achieved by early adopters of BSC. Reviews of their papers suggest the possibility of the results of BSC implementations being affected by other organizational factors.

Over the last few decades, academic researchers and practitioners have continued to study the subject of BSC in an effort to explain both successes and failures so that they may influence the development and implementation of BSC tools. This study contributes to the on-going effort to explain why the result of BSC implementations have been limited at best (Ittner et al., 2003; Ittner and Larcker, 1998b; Kaplan and Norton, 2007; Malina and Selto, 2001). In the current study, we provide a synthesis of the related literature pertaining to the behavioural implication of goal setting, perceived fairness and feedback and reward linkages, on individual managers’ job satisfaction, motivation and commitment.

Davis and Albright (2004) note that, “improved financial performance after the implementation of BSC relies on the identification of key leading indicators of desired financial performance. These leading indicators, typically non-financial in nature, are logically derived from establishing causal links between improved performance on non-financial measures and improved performance on selected financial measures.” Similarly, Kaplan and Norton (2007) contend that BSC approach provides a powerful means for translating a firm’s vision and strategy into a tool that effectively communicates strategic intent and motivates performance against established strategic goals.

Antle and Demski (1988) posit that performance measurement systems that have multiple measures provide managers with better tools for monitoring employees’ actions and guiding firm behaviour. Multiple measures are also known to provide better information on changes in the economy and competition (Banker et al., 2000). Feltham and Xie, 1994 uses an agency model to explore the economic impact of the use of multiple performance measures to deal with the problems of goal congruence. They posit that when a contract is based on non-congruent measures, effort allocation across tasks tend to be suboptimal, while the noisiness of single measures induces suboptimal effort intensity. The implication of this therefore, is that performance outcome in any performance management system will be affected by non-congruity in goal setting and performance measurement. For example, if a manger’s goals differ from those contained in the multiple measures performance indicators, the manager is more likely to exert effort that will be to the benefit of his personal goals to the detriment of the organizational goals.

Using a manufacturing organization, in a field study, Malina and Selto (2001) studied the effectiveness of BSC as a communication and control system. They found a positive and significant relationship between BSC, as a management control system and improvement in performance on BSC multiple measures. They also show that, as a result of the adequacy of BSC as a communication system, the managers in their study perceived an improvement in efficiency and profitability due to the improved performance on BSC measures. However, Ittner et al. (2003) provide a contradictory result regarding the association of BSC usage to financial performance. They present the result of an elaborate study of BSC implementation in the financial services industry and how this affects improvement in financial performance of the implementing organizations. They find from their sample that of the 20% users of BSC, over 75% reported not relying on business models that causally link performance drivers to performance outcomes. Hendricks, Menor and Weidman (2004) examined the association between BSC adoption and a firm’s performance following the implementation of a BSC system. Their test did not reveal significant performance improvements, but because a number of adopting firms began implementation in 2003, they argue that there was insufficient data to draw any firm conclusions about post-implementation performance. Hendricks, Menor and Weidman (2004) noted that “there has been little examination of the factors associated with the adoption of BSC and there is still need to demonstrate that the adoption and implementation of BSC is associated with improved financial performance.”

In summary, BSC, as a shift in paradigm, is focused on improving performance measurement systems through its motivational attributes; by providing clarification of vision and goals, management consensus on vision and strategy and focus on improved job performance. The use of multiple measures with clarity of set goals in BSC systems has also been shown to provide individuals an opportunity to view the system as fair (Lau and Sholihin, 2005) which is a basic attribute necessary for motivation of job performance, job satisfaction and acceptance of strategy. The next section will review these behaviours as they affect the multiple measures in a balanced scorecard.

Commitment to Goals

Locke and Latham (1990) define goal commitment as “one’s determination to reach a goal.” This broad definition of goal commitment is consistent with the current conceptualization of the construct within task goal theory. These definitions imply the individual’s intention to extend effort toward goal attainment, persistence in pursuing that goal over time and an unwillingness to lower or abandon that goal (Hollenbeck & Klein, 1987).

Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) posit that commitment in the work place can take various forms and may have effect on performance outcomes. They also argue that variations in definition and form of commitment constitute a source of challenge and provide an explanation for the inconsistency of the effect on performance outcomes. Therefore, it is important to properly explicate commitment as a construct in considering its implications for the behaviour of individuals in a BSC setting. Furthermore, to make the study of commitment relevant and to keep its value as an explanatory variable in this study, we find it necessary to distinguish commitment from motivation and general attitude. This, as observed by Tubbs (1994) will remove all conceptual ambiguities. Thus, commitment is viewed as an independent influence on behaviour that may lead to a persistence to reach the commitment target or goal irrespective of the existence of conflicting motives or attitudes and whether satisfaction is derived or not (Brown, 1996; DeShon and Landis, 1997; Rusbult and Farrell, 1983; Meyer and Herscovitch, 2001).

In comparing the social psychology and economic theories of manager’s commitment, as in Luft (2004), we argue that self-efficacy and utility of reaching a goal are positively correlated with managers’ goal commitment. This argument is consistent with the result of the study by Wofford and Goodwin (1992). Wofford and Goodwin (1992) conducted a meta-analysis to examine the antecedents and consequences of goal commitment using 78 goal-setting studies. They found that feedback, prior performance, self-efficacy, expectancy of goal attainment and task difficulty were statistically significant determinants of goal commitment. Wofford and Goodwin (1992) found that goal commitment significantly affected the achievement of goals but was not significantly related to performance. Hence, they suggested that goal achievement rather than performance be used as the outcome variable. On the relationship between commitment to goal and job performance, research has found that highly committed employees may perform better than less committed ones (Mowday, Porter and Dubin, 1974). Larson and Fukami (1984) also found that higher levels of organizational commitment are linked to higher levels of job performance. Meyer et al. (1989) also found that affective commitment correlated positively with the performance of lower-level managers in a large food service company. Therefore, performance measurements systems that generate employee commitment are more likely to have positive effects on job performance.

Webb (2004) undertook a study of manager’s commitment to goals in a strategic performance measurement system. He described strategic performance measurement system as “a set of causally linked nonfinancial and financial objectives, performance measures and goals designed to align managers' actions with an organization's strategy.” Webb identifies certain features unique to the cause-effect structure of a strategic performance measurement system such as BSC likely to affect goal commitment. Consistent with prior research he observes that multiple performance measures often contain difficult goals; but asserts that difficult goals are significantly more likely to lead to performance gains if individuals are committed to achieving them. Furthermore, results from his experiment conducted with experienced managers show that two features central to the strategic performance measurement system approach significantly affect goal commitment. The two features include: (1) the strength of the cause-effect links among the nonfinancial and financial performance measures contained in strategic performance measurement systems and (2) managers' beliefs in their ability to achieve the strategic performance measurement systems’ non-financial goals.

In summary, since there is consistency on the effect of commitment to goal on goal attainment and performance (Locke, Latham & Erez, 1988; Webb, 2004; Wofford and Goodwin, 1992) we propose that commitment to goal will have implications for the design of a performance management system that intends to improve employee performance. It also seems reasonable to assume that, in other to improve employee’s performance, the multiple measures in a BSC must possess certain attributes (for example, strategic linkages, fair processes, feedback, goal setting, expectancy of goal achievement, linkage to reward systems and so on) which the literature identifies as antecedent to commitment.

Motivation

The relevance of motivation as an intervening variable in the relationship between BSC and performance outcomes has been recognized and has been studied in the management accounting literature. Malina and Selto (2001) argue that increase in employee motivation is positively associated with improved performance. In a study of the effectiveness of BSC as a communication and strategic control tool, Malina and Selto (2001) used empirical interview and archival data to show that employees are motivated by effective communication, strategic alignments and effective management control and not by financial rewards only. They argue that a well-designed BSC and effective communication appears to motivate and influence lower level managers to conform their actions to company strategy.

Using a theoretical framework, Bouillon et al. (2006) adopted agency and stewardship theories to show that employees can be motivated more by goal congruence than by use of financial incentives. Managers are more likely to be motivated to behave in a way that is consistent with organizational objectives when they act as stewards as opposed to acting as agents; this also improves their sense of satisfaction (Bouillon et al., 2006).

Bonner et al. (2000) in a review of the effects of financial incentives on performance in laboratory tasks, report a mixed result in prior research on the relationship between financial rewards and employee motivation. However, the result of their review of the related incentive literature indicates that this relationship is a function of the type of reward system and task involved. Fessler (2003) also reports a mixed result on the relationship between monetary incentives, task attractiveness and task performance in a laboratory experiment. The result of his tests indicates that in one case the perceived task attractiveness and employee motivation is affected by the type of incentive plan (piece-rate or fixed-wage), while no effect is observed when the task was perceived as unattractive, in a complex task. He reports that this is not the same for a less complex task.

In summary, this review of literature shows a consensus akin to performance measurement systems being designed to motivate employee job performance by using certain motivational tools among other intervening variables. Motivation is important as a behavioural implication that induces action on the part of individuals (Pinder, 1998) and has great significance in a multiple performance measurement system (Kaplan and Norton, 1992, 1996b; Pinder, 1998; Malina and Selto, 2001). As noted else were in this review, Kaplan and Norton (1996b) assert that BSC measures motivate employee performance against established strategic goals. Therefore, a study of the motivational attributes of multiple measures in a BSC setting and its interaction with other factors, is of great value to our understanding of how multiple performance measurement systems affect individual behaviour and job performance. Furthermore, a review of what really motivates people and a reconsideration of the behaviourist approach may be timely for researchers and as well benefit managers, as they struggle to implement BSC.

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is an emotional reaction to an employee’s value response (Locke, 1969; Locke et al., 1970). Conventional wisdom suggests that job satisfaction is an important barometer in work organizations, but previous research indicates that it is not strongly related to job performance. Job satisfaction has been defined as “the extent to which people like (satisfaction) or dislike (dissatisfaction) their jobs” (Spector, 1997, p. 2). This definition suggests that job satisfaction is a general or global affective reaction that individuals hold about their job such as employee satisfaction with pay, job performance, supervisor and co-workers. Vroom (1964) argues that positive attitudes are conceptually equivalent to job satisfaction and conversely, that negative attitudes are equivalent to job dissatisfaction. Despite the fact that job satisfaction has been one of the most-studied concepts in the social and behavioural sciences, research has not resolved some of the more important and enduring questions that continue to puzzle researchers and managers. One useful stream of research has studied the causes and consequences of job satisfaction and its interrelationships with other important job-related variables. For example, in their meta-analytic construct validity results, Kinicki et al. (2002) showed that job characteristics, role states, group and organizational characteristics and leader relations are generally considered to be antecedents of job satisfaction and motivation, while citizenship behaviours, withdrawal cognitions, withdrawal behaviours and job performance are generally considered to be consequences of job satisfaction. This helps to clarify another long-running controversy in the literature regarding the specificity of causal paths and determining their true direction. For example, it has been unclear whether job satisfaction contributes to individual performance or visa-versa (Judge et al., 2001).

In summary, this review and other relationships highlighted by other sections of this paper, show that job satisfaction has a positive correlation with commitment and motivation, through job performance (Judge et al., 2001; Spector, 1997). The relationship between job satisfaction and performance is somewhat controversial and research is yet to resolve this nagging problem (Judge et al., 2001). Studies have shown that positive mood – including job satisfaction – is linked with altruistic motives and pro-social behaviour, such as motivation, organizational citizenship behaviour, etc. (Kinicki et al., 2002). Therefore, employees who are satisfied with the multiple performance measures in BSC environments are more likely to behave in a way that will enhance their ability to achieve the set goals. In the next section, we discuss key attributes of BSC that induce changes in individual behaviour and make general propositions regarding the relationships.

Determinants Of Individual Behavior Changes

Goal Setting

A goal can be generally defined as a predetermined or expected end result. The achievement of a goal is viewed as a valuable mark of success in task environments. The positive effect of goal setting on job satisfaction, motivation and commitment to goal achievement has had relatively consistent empirical support in the accounting, psychology and organizational behaviour literatures (Locke and Latham, 2002). There is also evidence in both laboratory settings using experimental designs and in field settings using quasi-experimental designs that establishes the usefulness of goal setting procedures in increasing productivity (Locke and Latham, 2002).

Prior literatures indicate that for goal setting to have relevance to job performance outcomes, the resultant change in behaviour must include commitment to the goal (Locke and Latham 1990; Locke, Latham & Erez, 1988; Locke and Somers, 1987). Locke et al., 1988 argue that a goal will not have any behavioural effects if there is no commitment; i.e. employees are not motivated to exert the necessary effort towards achieving a goal if they lack commitment to the goal. In their review of prior literature on determinants of goal commitment, Locke, Latham & Erez (1988, p. 23) note that “the effectiveness of goal setting, however, presupposes the existence of goal commitment.” The proposition that performance goals or standards play a significant role in human motivation is widely accepted by most researchers within the field of organizational Psychology (e.g. Bandura, 1986) and management accounting (Webb, 2004). In fact, Locke and Latham’s (1990) goal setting theory is currently one of the most popular theories of work motivation within the field of industrial and organizational psychology. However, while Locke’s (1968) early conceptualizations of goal setting theory are generally described as the origin of modern goal setting theory, the concept of personal standards, aspirations or goals has been acknowledged by psychological and organizational researchers as an important part of human motivation and performance since the early 1900s (Locke and Latham, 1990).

The two main postulates of goal setting theory include; a linear relationship between the difficulty of attainable goals and performance and the idea that specific, difficult goals lead to better performance than vague, easy or do-your-best Goals (Locke and Latham, 1990). Thorough tests by researchers over three decades have shown these relations to be among the most robust findings within the motivation and goal setting literature. Several meta-analyses of the goal difficulty-performance relationship have been conducted, all reporting consistent positive relationships between difficulty of goal and performance level. Mento, Steel and Karen’s (1987) meta-analysis compared the effects of setting hard goals vs. easy goals and the effects of setting specific hard goals to general do your best goals. They found a significant mean corrected effect size in 70 studies for goal difficulty, indicating that hard goals lead to better performance than easy goals and a significant mean effect size in 49 studies for goal specificity indicating that specific, hard goals are better than vague, easy or “do your best” goals. Wood, Mento and Locke (1987) using a meta-analytical approach that combined the effect sizes of 125 studies, hypothesized that task complexity would moderate the traditional performance effects of specific, difficult goals, such that the effects of goal difficulty and goal specificity would be stronger for simple tasks than for complex tasks. Tubbs (1986) compared 147 effect sizes in 87 studies to look for the effects of goal difficulty, goal specificity, goals and feedback combined and participation in goal setting on performance. Apart from the common prediction that specific, general goals would be associated with higher performance, it was hypothesized that goals combined with feedback would have a stronger effect on performance than goals alone. The hypotheses were supported, indicating that hard, specific goals, combined with feedback are associated with increases in performance.

Furthermore, Steers and Porter (1974) suggested that the motivational mechanism behind goal setting is that “effort (and consequently performance) is increased by providing individuals with clear targets toward which to direct their energies” (p. 435). Consequently goals or strategies that are not clear will prevent the organization from being used by its members in an effective manner (March & Simon, 1985). Kenis (1979) documents the relationship between budgetary systems characteristics, job-related attitudes and performance. He finds that budget goal clarity is positively related to job satisfaction and performance and negatively related to job related tension. The clearer the goals, the more likely the employees are to commit to the strategy and exert the necessary effort towards achieving the goals (Kenis, 1979). This is consistent with research that shows that individuals who set goals tend to produce more than those who do not set goals or who work under a more generalized goal condition such as “do your best” (Locke, 1968). Tosi et al. (1976) investigated the influence of several goal setting attributes on satisfaction using a longitudinal design. While the specific analyses of their study were quite complex and involved two organizations, little evidence was found that changes in “Goal Clarity and Relevance” factors were related to changes in job satisfaction. Contrary to the Tosi et al. (1976) position, Arvey and Dewhirst (1976) report the results of a study dealing with the effects of goal setting procedures on satisfaction among scientists and engineers. Four goal setting attributes were identified through factor analytic procedures and related to job satisfaction. Positive relationships between these goal setting attributes and satisfaction were found. It was also shown that various personality variables did not significantly moderate the goal setting-job satisfaction relationships. The implications of the above theoretical relationships for BSC is that clarity of strategic goals will positively affect individual satisfaction and satisfied employees are more likely to exert the necessary effort to ensure the achievement of the set goal (Kenis, 1979). This is consistent with the argument that the success of BSC and other strategic management processes is dependent on the employees understanding (clarity of the multiple goals) of the strategy (Kaplan and Norton, 2000).

In summary, the considerable support that has been found for the primary propositions of goal setting theory and evidence from the review of this body of research demonstrate that the impact of clear, specific, difficult and properly aligned goals, on performance generalizes across tasks, settings and subject populations. This has significant implication for the design and implementation of multiple performance measures and individual behaviour in a BSC setting. First, if BSC is a goal setting system (Kaplan and Norton, 1996c), it’s effectiveness in influencing individual behaviour and job performance will likely, in part, be dependent on the goal setting attributes identified in this review. In other words, the multiple goals on which performance in a BSC setting will be measured should be clear, concise, relevant and aligned to managers and employees goals in other to provide the required motivation, commitment and job satisfaction at the individual level. Secondly, multiplicity of performance goals in a BSC system creates the necessary difficulty (challenge) that the literature shows to be necessary in motivating and creating goal commitment.

Perception of Fairness

Individuals each seek a fair balance between what they put into their job and what they get out of it. Adam’s (1965) equity theory calls these inputs and outputs. Equity theory argues that individuals’ form perceptions of what constitutes a fair balance or trade of inputs and outputs by comparing own situation with other 'referents' (reference points or examples) in the market place (Adams, 1956). Adams (1965) also argues that individuals are also influenced by colleagues, friends and partners in establishing these benchmarks and in formulating their own responses to them in relation to own ratio of inputs to outputs. If individuals feel that inputs are fairly and adequately rewarded by outputs then they are satisfied in their work and motivated to continue inputting at the same level. On the other hand, a feeling of unfairness will bring dissatisfaction and individuals are often demotivated in relation to job and organization. Relative deprivation theory holds that individuals will exhibit feelings of injustice when rewards are distributed in a particular pattern that triggers unfavourable comparisons; while unfavourable comparisons, in turn, cause feelings of deprivation that are manifest in dissatisfaction and perceptions of unfairness (Crosby, 1976).

Bartol, Durham and Poon (2001) document two primary types of organizational justice that have been identified in the literature; distributive justice and procedural justice. They define the two forms of organizational justice as follows; “Distributive justice refers to the perceived fairness of an individual's outcomes in proportion to the individual's inputs as compared with the outcomes and inputs of relevant others. In contrast, procedural justice refers to the fairness of the process used in making and implementing resource allocation decisions.” These definitions are adequately grounded in the equity theory. Bartol, Durham and Poon (2001) also document the position of Tyler (1989, 1994) and Tyler and Lind (1992); “that people care about their standing in a group and provide evidence that information about individuals' status or standing within a group influences justice perceptions.”

Wentzel (2002, p. 247) notes “that fairness perceptions indirectly translate into improved performance via goal commitment.” Using survey methodology in constrained budgetary conditions, the literature provides empirical evidence in support of the behavioural implication of increased participation during budgeting. Specifically, Wentzel (2002) provides support for the positive relationship between perception of fairness and employee goal commitment. The results of the study were supported using two aspects of the theory of organizational justice: distributive and procedural justice. Distributive justice refers to the fairness of the actual outcome an employee receives and procedural justice relates to the fairness of the procedures used to determine those distributive outcomes (Wentzel, 2002). The research by Wentzel (2002) provides strong evidence that participation influences fairness perceptions, which leads to goal commitment, which has a direct influence on performance.

One major purpose for management control systems and similarly BSC, is the expected contribution in motivating and evaluating the performance of employees. These outcome effects of the performance measurement systems (motivation, commitment, job satisfaction and performance) have been shown to be indirect through certain intervening variables including employee’s perception of the fairness of the performance evaluation process and performance targets (Libby 2001). In summary, the literature provides sufficient evidence to show that employee perception of both distributive and procedural justice influence behaviour. Notably, any system of work relationships must possess some level of equity or be perceived as equitable in its processes and resource allocation in other to be motivationally effective. According to equity theory (Adams, 1963), perceptions of an unfair distribution of work rewards relative to work inputs create tension within an individual and the individual is motivated to resolve the tension. Similarly, other research suggests that perception of unfairness in the performance measurement process can lower managers’ motivation (Ittner et al., 2003). The implication of these for the current paper is that the effectiveness of BSC in inducing behavioural changes in individuals, including job performance, is likely to be affected by the employees’ perception of fairness of both the processes and goals (Kaplan and Norton (1996); Kaplan and Atkinson 1998; Ittner et al., 2003). Furthermore, this review of literature suggests that, to obtain acceptance of the multiple goals in a BSC, requires that the process of setting the goals is perceived by the employees as fair (Libby, 2001)

As argued by Kaplan and Norton (1996), the adoption of multiple measures of performance (e.g. BSC) may be instrumental in improving employees’ perception of the fairness of the performance measurement system in organizations; which may lead to changes in behaviour (Ittner et al., 2003). When employees perceive BSC processes as fair, they are motivated and are more likely to be committed to the strategic goals indicated by BSC and in turn derive satisfaction in doing their assigned jobs. Therefore it is reasonable to assume from the on-going discussion that, if job satisfaction, motivation and commitment are work inputs, then an employee’s response to a perceived unfairness could be a lower level of job satisfaction, a poor sense of motivation and a lack of commitment to organizational strategy.

Performance Reward Systems

The idea that dangling money and other goodies in front of people will "motivate" them to work harder is the conventional wisdom in our society. Consistent with this anecdotal evidence, there are abundant research studies that attempt to associate financial incentives and rewards to changes in individual behaviour and performance. However, the results have not been consistent. In this section, we will review a few of these recent studies.

Consistent with the popular argument, Ducharme, Singh and Podolsky (2005, p. 46) note that “an organization’s compensation and reward system has always been one of the most important determinants of its survival and growth.” They argue that expectancy theory may be used in explaining the motivational aspects of employee pay performance relationships. As discussed in their paper, expectancy theory postulates that three conditions must be met for employees to exert extra effort. There must be expectancy that a given input will yield an acceptable level of performance, an instrumentality – the level of performance will have specific consequences and valence – i.e., the consequence must be valued (Ducharme et al., 2005).

Ducharme et al. (2005) argue that emphasis should not be only on designing “well-thought-out” appraisal and reward systems, but that the linkages between the reward (pay) systems and the performance measures is made clear. They used survey data from the 2002 Workplace and Employee Survey in Canada and carried out a statistical comparison of “pay satisfaction” among four groups of individuals differentiated by the performance appraisal and pay satisfaction variables. Their result indicates that individuals who received performance appraisals that were linked to pay demonstrated significantly higher pay satisfaction than all other groups. Furthermore, they find that “achieving instrumentality or line of sight, could be as simple as establishing a performance appraisal mechanism within the organization, regardless of whether that performance appraisal is tied to performance pay.”

Organizational support theory (Eisenberger et al., 1986) postulates that, favourable opportunities for rewards convey a positive valuation of employees’ contributions and thus contribute to increases in commitment. Similarly, opportunities for recognition, pay and promotion, are positively associated with commitment to organizational strategy; as found by Gaertner and Nollen (1989). Mottaz (1998) explained such findings on the basis of employees’ exchange of emotional attachment for benefits received from the organization. Gregersen (1992) suggested that favourable rewards led to greater affective commitment by conveying the firm’s supportiveness and dependability. Gaertner and Nollen (1989) suggested that rewards increased employees’ perceptions of organizational support; which is an antecedent to affective commitment. Rhoades et al. (2001) defined affective commitment as the employees’ emotional bonding to their organization. The explanations for the relationships between organizational rewards and employee commitment are consistent with the view that perceived organizational support may mediate these relationships (Eisenberger et al., 2001). Allen et al. (1990) found with one employee sample but not another that perceived organizational support mediated the relationship between promotional opportunities and affective commitment.

Consistent with the organizational support theory, the management accounting literature has also been equivocal on the relationship between performance measures and reward systems. In an experimental study involving laboratory tasks, Bonner, Hastie and Sprinkle (2000), study the effects of financial incentives on performance. They argue that, theoretically, the value relevance of rewards as a motivational tool in organizations is operationalized by the performance reward linkages. Bonner et al. (2000) also show that the effectiveness of a reward system varies inversely with task complexity. They argue that the more complex a task, the less effective rewards are in motivating employees’ task performance. They motivate their research with related studies that provide conflicting evidence on the relationship between performance and financial incentives. Therefore, they call for studies to identify the possible variables that interact with financial incentives in affecting task performance. They posit that task type and incentive type play a role in the relationship between financial incentives and task performance. Although their study is not on multiple performance measurement systems or BSC, the findings have great relevance to these systems.

Fessler (2003), in an experimental research, where he engaged his subjects in a complex task under two types of incentive plans (fixed wage and piece rate), found that perception of task attractiveness and task performance interact with the performance and rewards relationship. Ittner and Larcker (2002) examined the determinants of performance measure choices in worker incentive plans for non-management employees. Their study was based on a cross sectional survey data collected from manufacturing and service organizations. They observe that the use of reward systems to foster organizational change, attract and maintain key personnel and control compensation costs or make pay more variable with firm financial performance could be contrary to the objective of motivating employee through incentive plans. However, they claim that nonfinancial measures may be more useful for promoting organizational change and provide strong directions to workers and make communication of the effect of the worker’s action on new performance goals a lot easier (Kaplan and Norton, 1996), which in turn serves as a good way to motivate employees (Feltham and Xie, 1994).

In a case study involving the examination of the impact of weights attached to different performance measures in a subjective BSC bonus plan adopted by a major service firm, Ittner, Larcker and Meyer (2003) find that a change from a Performance Incentive Plan to BSC based reward system did not provide significant change in the manager’s understanding of the strategic goals or their connections to the managers’ actions. As noted by Ittner et al. (2003), “the branch manager’s felt less comfortable with the adequacy of the information provided to them about progress toward the multiple business goals.” This is however contrary to the suggestion that the balance scorecard renders subjective rewards systems easier and more defensible to administer (Kaplan and Norton, 1996) or the indications by other researchers that subjectivity in the reward system can improve incentive contracting and mitigate distortions in managerial effort. What has been observed is that subjectivity of BSC based rewards system brings about certain discretionary behaviours on the part of the supervisors and makes financial performance a primary determinant of rewards and introduces other undeserving performance measures while ignoring certain of the behavioural components of BSC measures (Ittner, Larcker and Meyer, 2003).

In summary, rewards and incentives have been shown to be very informative and useful in the development and implementation of performance management systems like BSC. The review of literature provide evidence on the usefulness of linking rewards to performance and ensuring that the linkage is clearly communicated to individuals in the organization. This clarity and alignment of employee performance expectations with agency missions and goals has implication for the balanced scorecard. Effective incentive programs that motivate all employees and reward those employees, teams and organizational units whose performance exceeds expectations, can help organizations maximize strategic outcomes, however, the result from the review of the literature on performance based incentive systems indicate that this outcome is dependent on how the incentive system is perceived by the employees’ and how it affects their attitudes and behaviour. Prior research in this area has provided different results as to the cause and effect relationship between performance-based reward systems and expected outcomes.

Performance Feedback

Feedback is an embedded attribute of strategic management control systems (Kaplan and Norton, 2001) that provides individuals in the organization with information about actual performance (Ittner and Larcker, 2002) which can be used by both the supervisor and employee for enhancing future performance. Wheelen and Hunger (1992) state that: “Control follows planning. It ensures that the organization is achieving what it set out to accomplish…the control process compares performance with desired results and provides the feedback necessary for management to evaluate results and take corrective action.” An effective balanced scorecard will most likely provide reliable feedback for management control and performance evaluation (Malina and Selto, 2001). The amount of feedback and type of feedback is referred to as the feedback environment (Herold and Parsons, 1985). Annett (1969) identified two components of the feedback environment; spontaneous occurring feedback and augmented feedback.

Prior studies indicate that feedback can emanate from different sources in the work environment. Ilgen et al. (1979) identify three sources of feedback in the work environment: (1) other individuals that evaluate the employee’s performance (colleagues and supervisors). (2) The task environment (the job itself). (3) The individuals’ own self-judgement. Consistent with the on-going,

Hackman and Oldham (1975) theorize that feedback predicts favourable work attitude. In Hackman and Oldham’s theory, feedback is one of five core job characteristics associated with good personal and work outcomes, including job satisfaction, motivation and commitment. However, research on the relationship between performance feedback and employee attitudes towards work has yielded mixed results. Dodd and Ganster (1996) provided evidence, in a study where autonomy, variety and feedback were manipulated, that feedback showed no effect on job satisfaction. In a field experiment Tziner and Latham (1989) introduced goal-setting and feedback and revealed an increase in work satisfaction and commitment. The result could not confirm that feedback on its own could increase satisfaction and commitment. The implication of this inconsistent result is that the relationship between feedback and job attitudes is likely to be affected by other variables.

Herold and Greller (1977) noted two distinctions of feedback. These are positive feedback (communicating a job well done to the employee) and negative feedback (communicating criticism of an employees work performance). They showed that this distinction is important, as positive and negative feedback are not end points on the same dimension. Instead, positive and negative feedback appear to be fairly independent factors and should be assessed independently from each other (Herold and Parsons, 1985). Ilgen et al. (1979) conclude that positive feedback is generally more accurately perceived than negative feedback. The reason for this is that negative feedback may be denied by recipient because of unwillingness to accept this knowledge. Also, Waung and Highhouse (1997) conclude that fear of interpersonal conflict is a major reason for supervisors providing less negative feedback. Much as negative feedback appears to be more problematic than positive feedback, researchers have found that negative (corrective) feedback improved service performance in service personnel (Waldersee and Luthans, 1994)

In summary, the implication of the above review of the feedback literature in a BSC environment is that implementing organizations must understand employee responses to feedback and ensure that feedback is used in proper combination with other intervening factors identified in the literature. Also an additional implication is that when positive feedback is given there is appropriate reinforcement and when negative feedback is given, corrective measures are appropriately communicated. Studies on the relationship between performance feedback and employee behaviour and strategic outcomes have been mixed in their results. This is evident from the review of the literature. This inconsistency has continued to elicit research on the effect of feedback on outcome variables including employee behaviour. The intervening effects of other variables (participation, goal setting and feedback sign) have been explored by prior research in an effort to explain the inconsistencies; however, most of the research (laboratory and field studies) on goal setting and feedback suffer from common limitations. The tasks used are relatively simple or simulated; the goals are established arbitrarily or based on past performance. An interesting extension of the literature will include a longitudinal study in a field setting to ascertain the effect of feedback conditions on employee job satisfaction and job attitudes. Also it may be necessary to study the effect of the quality of feedback on employee job attitude and satisfaction.

Summary and Conclusion

This paper reviewed the attributes of multiple performance measures in a BSC environment and analysed their impact on individual behaviour and performance outcomes. More specifically, it discussed the role of goal setting, perception of fairness, reward linkages and performance feedback in the relationship between multiple performance measurement systems and job performance, motivation, commitment to goal and job satisfaction. Also presented are proposed theoretical models that synthesize the relationships between the multiple performance measurements BSC attributes and the expected changes in behaviour and job performance.

Overall, the use of multiple performance measures in a BSC as proposed by Kaplan and Norton (1992, 1993), seems to have provided organizations with an alternative performance measurement system that overcomes the deficiencies associated with the traditional financial measurement system. However, anecdotal evidence and result of empirical, laboratory and survey studies in the literature are inconsistent at the minimum on the effectiveness of BSC in changing individual behaviour. This has increased the level of concern and investigation of its effectiveness by both the academic researchers and practitioners are continuing. This suggests that more research is needed in other to really ascertain the effectiveness of the use of multiple performance measures and the balance scorecard as a strategic management tool in changing individual behaviour and improving job performance.

A synthesis of the literature also suggests that the conflicting findings of research studies could be as a result of the differences in implementation procedures and resources distribution methods of organizational and employee perception of these differences. Various psychological and personality theories were found valuable in developing “theoretical frameworks” that could possibly explaining the differences in results and contribute to future research.

Furthermore, this review also identified key intervening variables in BSC performance relationship. In exploring the cause and effect relationships between these intervening variables and BSC job performance relationship, another issue of importance includes the possibility that the various intervening variables might be measuring the same construct or are being confounded by other variables.

Finally, a reasonable extension of the existing literature could involve a study of whether the level of commitment, motivation and job satisfaction will co-vary in a multiple performance measurement environment when the level of perceived fairness, goal setting and feedback quality is manipulated in an experimental setting and the rewards effect is controlled. Thorough examination of the effectiveness of the implementation of BSC across different types of organizations, industry sizes, management styles and cultures, over a long period of time may not only substantially increase our knowledge about the role and significance of BSC and the use of multiple performance measures in individual behaviour changes, but could also explain the inherent differences in research results.

References

- Adams, J.S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange, In: L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267-299. New York: Academic Press.

- Allen, N.J. & Meyer, J.P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53, 337-348.

- Annett, J. (1969). Feedback and human behaviour. Baltimore, MD: Penguin.

- Arvey, R.D, Dewhirst, H.D. & Boling J.C. (1976). Relationships between goal clarity, participation in goal setting and personality characteristics on job satisfaction in a scientific organization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61(1), 103-105.

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Banker, R.D, Chang, H. & Pizzini. M.J. (2004). The balanced scorecard judgmental effects of performance measures linked to strategy. The Accounting Review. 79(1), 1-23.

- Bartol, K,M,, Durham, C.C. & Poon J.M. (2001). Influence of performance evaluation rating segmentation on motivation and fairness perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1106-1119.

- Bouillon, M.L., Gary D.F., Martin T.S. Jr. & Timothy D.W. (2006). The economic benefit of goal congruence and implication for management control systems. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 25, 256-298.

- Boyne, G.A. (2003). Sources of public service improvement: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 13(3), 367-394.

- Briers, M.L., Chee, W.C., Nen-Chen, R.W. & Peter, F.L. (1999). The effects of alternative types of feedback on product-related decision performance: A research note. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 1, 75-92.

- Bonner, E.S., Hastie, R., Sprinkle, G.B. & Young S.M. (2000). A review of the effects of financial incentives on performance in laboratory tasks: Implications for management accounting. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 12, 19-43.

- Brown, R.B. (1996). Organizational commitment: Clarifying the concept and simplifying the existing construct typology. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 49, 230-251.

- Caldwell, D.M., Jennifer A.C. & O'Reilly, C.A. (1990). Building organizational commitment: A multi-firm study. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 245-261.

- Crosby, F. (1976). A model of egoistic relative deprivation. Psychological Review, 83, 85-113.

- Davis, S. & Albright, T. (2004). An investigation of the effect of balanced scorecard implementation on financial performance. Management Accounting Research, 15, 135-153.

- Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York: Plenum.

- DeNisi, S.D. & Pritchard, R.D. (2006). Performance appraisal, performance management and improving individual performance: A motivational framework. Management and Organization Review, 2(2), 253-277.

- DeShon, R.P. & Landis, R.S. (1997). The dimensionality of the Hollenbeck, Williams and Klein (1989) measure of goal commitment on complex tasks. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 70,105-116.

- Dodd, N.G. & Ganster, D.C. (1996). The interactive effects of task variety, autonomy and feedback on attitudes and performance. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 17, 329-347.

- Ducharme, M.J, Singh, P. & Podolsky, M. (2005). Exploring the links between performance appraisals and pay satisfaction. Compensation and Benefits Review, 37, 46-52.

- Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P. & Davis-LaMastro, V. (1990). Perceived organization support and employee diligence commitment and innovation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 51-59.

- Eisenberger, R., Rhoades, L. & Cameron. J. (1999). Does pay for performance increase or decrease perceived self-determination and intrinsic motivation? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1026-1040.

- Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P.D. & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 42-51.

- Feltham, G. & Xie, J. (1994). Performance measure congruity and diversity in multi-task principal/agent relations. The Accounting Review, 69, 429-453.

- Fessler, N.J. (2003). Experimental evidence on the links among monetary incentives, task attractiveness and task performance. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 15, 161-176.

- Fletcher, C. (1986). The effects of performance review in appraisal: Evidence and Implications. Journal of Management Development, 5, 3-12.

- Fletcher, C. & Williams, R. (1996). Performance management, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. British Journal of Management, 7, 169-179.

- Gersbach, H. (1998). On the equivalence of general and specific control in organizations. Management Science (May), 730-737.

- Gaertner, K.N. & Nollen, S.D. (1989). Career experiences, perceptions of employment practices and psychological commitment to the organization. Human Relations, 42, 975-991.

- Greenberg, J. (1990). Organizational justice: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. Journal of Management, 16, 399-432.

- Gregersen, H.B. (1992). Commitments to a parent company and a local work unit during repatriation. Personnel Psychology, 45, 29-54.

- Hackman, J.R. & Oldham, G.R.(1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology. 60(2), 159-170.

- Herold, D.M. & Parsons C.K. (1985). Assessing the feedback environment in work organizations: Development of the job feedback survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70, 290-305.

- Herscovitch, L. & Meyer J.P. (2002). Commitment to organizational change: Extension of a three-component model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 474-487.

- Hollenbeck, J.R, Williams, C.R. & Klein, H.J. (1989). An empirical examination of the antecedents of commitment to difficult goals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 18-24.

- Iaffaldano, M.T. & Muchinsky, P.M. (1985). Job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 97(2), 251-273.

- Ilgen, D.R., Fisher, C.D.F. & Susan, M.T. (1979). Consequences of individual feedback on behaviour in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64, 349-71.

- Ittner, C.D. & Larcker D.F. (1997). Quality strategy, strategic control systems and organizational performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 22(3/4), 293-314.

- Ittner, C.D. & Larcker D.F. (1998a). Are non-financial measures leading indicators of financial performance? An analysis of customer satisfaction. Journal of Accounting Research, 26(Supplement), 1-34.

- Ittner, C.D. & D.F. Larcker. (1998b). Innovations in performance measurement: Trends and research implications. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10, 205-238.

- Ittner, C.D. & Larcker, D.F. (2002). Determinants of performance measure choices in worker incentive plans. Journal of Labour Economics, 20(2), 58-89.

- Ittner, C.D., Larcker, D.F. & Meyer M.W. (2003). Subjectivity and the weighting of performance measures: Evidence from a balanced scorecard. The Accounting Review, 78(3), 725-758.

- Judge, T.A., Parker, S., Colbert, A.E., Heller, D. & Ilies, R. (2001a). Job satisfaction: A cross-cultural review. In N. Anderson, D.S. Ones, H.K. Sinangil and C. Viswesvaran, eds. Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology, 2, 25-52. London: Sage.

- Judge, T.A., Thoreson, C.J., Bono, J.E. & Patton, G.K. (2001b). the job satisfaction-job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(33), 76-407.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1992). The balanced scorecard measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, (January-February), 71-79.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1993). Putting the balanced scorecard to work. Harvard Business Review, (September-October), 143-142.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1996a). Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system. Harvard Business Review, (January-February), 75-85.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1996b). The Balanced Scorecard. Boston, MA; Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (1996c). Linking the balanced scorecard to strategy. California Management Review, (Fall), 53-79.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2000). The strategy-focused organization. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2001a). Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management: Part I. Accounting Horizons, 15(1), 87-104.

- Kaplan, R.S. & Norton, D.P. (2001b). Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management: Part II. Accounting Horizons, 15(2), 147-160.

- Kenis, I. (1979). Effects of budgetary goal characteristics on managerial attitudes and performance. Accounting Review, 54(4), 707-722.

- Kim, S. (2005). Individual-level factors and organizational performance in government organizations. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 15(2), 245-261.

- Kinicki, A.J., McKee-Ryan, F.M., Schriesheim, C.A. & Carson, K.P. (2002). Assessing the construct validity of the job descriptive index: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 14-32.

- Larson, E.W. & Fukami, C.V. (1984). Relationships between worker behaviour and commitment to the organization and union. Academy of Management Proceedings, 34, 222-226.

- Lau, C.M. & Sharon, L.C.T. (2006). The effects of procedural fairness and interpersonal trust on job tension in budgeting. Management Accounting Research, 17, 171-186.

- Lau, C.M. & Sholihin, M. (2005). Financial and non-financial performance measures: How do they affect job satisfaction? The British Accounting Review, 37, 389-413.

- Leventhal, G.S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchanges: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27-55). New York: Plenum.

- Leventhal, G.S, Karuza, J. & Fry, W.R. (1980). Beyond fairness: A theory of allocation preferences. In G. Milkula (Ed.), Justice and social interaction (pp. 167-218). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Lindquist, T. (1995). Fairness as an antecedent to participative budgeting: Examining the effects of distributive justice, procedural justice and referent cognitions on satisfaction and performance. Management Accounting Research, 7, 122-147.

- Libby, T. (2001). Referent cognitions and budgetary fairness: A research note. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 13, 91-105.

- Lipe, M.G. & Salterio,S. (2000). The balanced scorecard: Judgmental effects of information organization and diversity. The Accounting Review, 75(3), 283-298.

- Locke, E.A. (1968). Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives. Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance, 3, 157-189.

- Locke, E.A. (1969). What is job satisfaction? Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance, 4, 309-335.

- Locke, E.A., Cartledge, N. & Kneer, C.A. (1970). Studies of the relationship between satisfaction and goal setting and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 5, 135-158.

- Locke, E.A. & Somers R.L. (1987). The effects of goal emphasis on performance on a complex task. Journal of Management Studies, 24, 406-411.

- Locke, E.A., Latham G.P. & Erez, M. (1988). The determinants of goal commitment. Academy of Management Review, 13(1), 23-39.

- Locke, E.A. & Latham, G.P.(1990). A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Locke, E.A. & Latham, G.P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705-717.

- Luft, J.L. & Shields, M.D. (2003). Mapping management accounting: graphics and guidelines for theory-consistent empirical research. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 28 (2/3), 169-249.

- Luft, J.L. (2004). Discussion of manager’s commitment to the goals contained in a strategic performance measurement system. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(4), 959-964.

- Malina, M.A. & Selto, F.H. (2001). Communicating and controlling strategy: An empirical study of the effectiveness of the balanced scorecard. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 13, 47-90.

- Meyer J.P. & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 299-326.

- Meyer, J.P., Paunonen S.V., Gellatly I.R., Goffn R.D. & Jackson, D.N. (1989). Organizational commitment and job performance: It’s the nature of the commitment that counts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(1), 152-56.

- Meyer, J.P. & Allen, N.J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61-89.

- Meyer J.P., Becker, T.E. & Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(6), 991-1007.

- Mottaz, C.J. (1988). Determinants of organizational commitment. Human Relations, 41, 467-482.

- Mowday, R.T, Porter, L.W. & Dubin, R. (1974). Unit performance, situational factors and employee attitudes in spatially separated work units. Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance, 12(2), 231-248.

- McKenzie, F.C & Schilling, M.D. (1998). Avoiding performance measurement traps: Ensuring effective incentive designs and implementation. Compensation and Benefits Review, 30(4), 57-65.

- Pinder, C.C. (1998). Work motivation in organizational behaviour. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- Pulakos, E.D. (2004). A Roadmap for Developing, Implementing and Evaluating Performance Management Systems. Alexandria, VA: SHRM Foundation.

- Rappaport, A. (1999). New thinking on how to link executive pay to performance. Harvard Business Review, (March-April), 91-101.

- Rucci, A.J, Steven P.K. & Richard T.Q. (1998). The employee-customer profit chain at sears. Harvard Business Review, 20(2), 83-97.

- Rusbult, C.E. & Dan, F. (1983). A longitudinal test of the investment model: The impact of job satisfaction, job commitment and turnover of variations in reward, costs, alternatives and investments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 429-438.

- Sawyer, J.E. (1992). Goal and process clarity: Specification of multiple constructs of role ambiguity and a structural equation model of their antecedents and consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(2), 130-142.

- Skinner, B.F. (1938). The behaviour of organisms. New York: Appleton- Century-Crofts.

- Spector, P.E. (1997). Job satisfaction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Steers, R.M. & Porter, L.W. (1974). The role of task-goal attributes in employee performance. Psychology Bulletin, 81, 434-453.

- Tosi, H., Hunter, J., Chesser, R., Tarter, J.R. & Carroll, S. (1976). How real are changes induced by management by objectives. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(2) 276-306

- Tubbs, M.E. (1986). Goal setting: A meta-analytic examination of the empirical evidence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 474-478.

- Tubbs, M.E. (1994). Commitment and the role of ability in motivation: A reply to Wright, O’Leary-Kelly, Klein and Hollenbeck. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 804-811.

- Tyler, T.R. (1989). The psychology of procedural justice: A test of the group-value model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 830-838.

- Tyler, T.R. & Lind, E.A. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 115-191. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Tyler, T.R. (1994). Psychological models of the justice motive: Antecedents of distributive and procedural justice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 850-863.

- Tziner, A. & Latham G.P. (1989). The effects of appraisal instrument, feedback and goal-setting on worker satisfaction and commitment. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 10, 145-153.

- Ullrich M.J. & Tuttle, B. (2004). The effects of comprehensive information reporting systems and economic incentives on manager’s time-planning decisions. Behavioural Research in Accounting. 16, 89-105.

- Vroom, V. 1964. Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

- Waldersee, R. & Luthans, F. (1994). The impact of positive and corrective feedback on customer’s service performance. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 15: 83-95.

- Waung, M. & Highhouse S. (1997). Fear of conflict and empathic buffering: Two explanations for the inflation of performance feedback. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 71, 37-54.

- Webb, R.A. (2004). Manager’s commitment to goals contained in a strategic performance measurement system. Contemporary Accounting Research, 21(4), 925-958.

- Wentzel, K. (2002). The influence of fairness perceptions and goal commitment on manager’s performance in a budget setting. Behavioural Research in Accounting, 14, 247-271.

- Wheelen, T.L. & Hunger, J.D. (1992). Strategic Management and Business Policy. Fourth Edition, New York: Addison Wesley Publishing Company.

- Wofford, J.C. & Vicki, L.G. (1992). Meta-analysis of the antecedents of personal goal level and of the antecedents and consequences of goal commitment. Journal of Management, 18(3), 595-615.

- Wood, R.E., Mento, A.J. & Locke, E.A. (1987). Task complexity as a moderator of goal effects: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 416-425.