Research Article: 2019 Vol: 23 Issue: 5

Managerial Overconfidence and Labor Investment Efficiency

Kyoungwon Mo, Chung-Ang University

Kyung Jin Park, Myongji University

YoungJin Kim, Hawaii Pacific University

Abstract

Managerial overconfidence is known as a cognitive bias which leads managers to overestimate their ability and judgments and induces riskier capital investments. Research explored the influence of managerial overconfidence on labor investment efficiency. Author found a significantly positive association between CEO overconfidence and labor overinvestment. This result indicates that overconfident managers tend to invest more in labor, thus worsening labor investment efficiency under labor overinvestment. Further analysis reveals that internal funds increase negative impact of the managerial overconfidence on labor investment efficiency.

Keywords

Managerial Overconfidence, Labor Investment, Investment Efficiency, Agency Problem.

JEL Classifications

G31; G34; G41

Introduction

Managerial overconfidence is a cognitive bias that induces managers to believe that they are more capable than or that their firms will perform better than average competitors (Kidd 1970; Larwood Whittaker 1977; Moore 1977; Svenson 1981; Alicke 1985; Camerer Lavallo 1999). Such overestimation of their abilities and judgements leads managers to seek more aggressive and risky ventures and invest excessively beyond the optimal level. This negative relation between managerial overconfidence and investment efficiency is empirically shown by Heaton (2002); Malmendier Tate (2005), and Campbell et al. (2011).

Author extend ed th e stream of studies by examining investments in labor, which is an important factor of production that has not been sufficiently documented thus far. One reason why labor investment has received less attention than physical capital investment may be related to the convention in classical microeconomics of considering labor inputs as simply varying in accordance with sales. The traditional labor economics literature argues that labor costs have more variable cost components than capital costs, while recent studies suggest that a sizeable portion of labor costs are fixed (Oi 1962; Farmer 1985; Hamermesh 1996). As such, decisions regarding labor investment are as important for increasing firm value as physical ca pital investment (Merz Yashiv 2007).

After relating th o se two factors and examine d the association between managerial overconfidence and labor investment efficiency. Unlike other physical capital investments, labor investment may not return visible and clear cash inflows (Schultz 1961; Weisbrod 1961; Ashton Green 1996; Wolf 2002). Hence, decisions regarding labor investment may more heavily depend on managers’ subjective judgments than physical capital investments. Considering this characteristic, author believe d that labor investment is more suitable for examining the impact of managerial overconfidence on investment. Given the difficulty of observing a clear relation between labor investment and prior cash inflow, labor investment depends more he avily on managers’ future predictions. As overconfident CEOs make more positive predictions, and expect ed overconfident CEOs to increase labor investment, resulting in higher and lower investment efficiency for the labor underinvestment and overinvestment subsample, respectively. Hence, Author predict ed that the influence of CEO overconfidence on labor invest ment efficiency depends on the level of labor overinvestment or underinvestment.

For the empirical analysis, study need to measure both labor investment efficiency and CEO overconfidence. For the former, research follow s Pinnuck Lillis (2007) Li (2011); and Jung et al. (2014). The firm’s net hiring or the ch ange in the number of employees is used as proxy for the firm’s labor investment, and following prior literature, the actual net hiring is regressed on a battery of factors revealing the firm’s econo mic and financial fundamentals. The absolute difference between the actual net hiring and fitted net hiring obtained from this regression is defined as the degree of labor investment inefficiency. Next, following Malmendier Tate (2005) and Campbell et al (2011), managerial overconfidence is measured using the CEO’s net stock purchases and stock option holdings and exercising decisions.

This study contributes to the managerial overconfidence literature. CEOs’ personal characteristics have recently been c onsidered an integral factor in a corporation’s behavior, and managers’ overconfidence has been studied for its effect on various corporate decisions, such as investment related decisions (Hiller Hambrick 2005; Malmendier Tate 2005; Campbell et al. 2011), and the internal dec ision making structure (Picone et al., 2014; Haynes et al., 2015). Author found an additional influence of managerial overconfidence on corporate behavior, as seen in labor investment.

This study also contributes to the labor investment literature. Labor is recognized as an integral production factor for the firm’s long term survival and growth (Franke 1994; Becker Gerhart 1996; Gimeno et al. 1997 ; Bartlett Ghoshal 2002). In addition , labor costs account for two thirds of overall value added in the US economy (Hamermesh 1996; Bernanke 2010). Hence, the impact of managerial overconfidence on labor investment efficiency is essential for examining its association with the firm’s long t erm performance and for understanding the influence of CEO overconfidence.

The study first reviews the related literature and develops research hypothesis. Next, explain s the research design to empirically examine research hypothesis and present research results. The conclusion summarizes and discusses the results.

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Managerial Overconfidence and Corporate Investments

In the psychology literature, overconfidence is defined as an individual’s overoptimistic estimation of his or her abilit ies or judgments (Miller Ross 1975; Kruger 1999; Alicke Govorun 2005). M anagerial overconfidence is specifically described as a better than average belief and asymmetric attribution of causality. In other words, overconfident managers believe that they are better than the average competitor in terms of their ability and judgments and display a higher tendency of attributing success ful outcomes to the mselve s, while attributing unsuccessful results to exterior factors (Kidd 1970; Larwood Whittaker 1977; Moore 1977; Svenson 1981; Alicke 1985; Camerer Lavallo 1999).

Previous overconfidence related psychology studies have furt her analyzed the impact of overconfidence on individual behaviors in three ways: overestimation of one’s own ability, over precision of one’s own judgments , and over placement of one’s own performance over that of others (Picone et al., 2014). Accordingly the influence of managerial overconfidence on corporate decisions can be threefold (Lai et al., 2017). First, the CEO’s overestimation of his or her abilit ies in turn leads manager s to overestimate the firm’s resources (Malmendier Tate 2005). This induces overconfident CEOs to seek more risky investment opportunities and often to select those beyond the firm’s availability (Campbell et al. 2011). On the other hand , the over precision induced by overconfidence allows the CEO to be less cautious whil e making decision s , and this can reduce the decision making time (Hiller Hambrick 2005). In addition, the associated over placement causes manager to prefer a centralized corporate structure and a monopolize d internal decision making process (Haynes et al., 2015).

Hence, when research focus es on the predicted impact of manager s ’ overconfidence on investment decisions, overconfident CEOs are expected to pursue aggressive and risky investment strategies and to overinvest , as they overestimate the resu lts of investments. Heaton (2002) and Malmendier Tate (2005) show that manager s ’ choice of a suboptimal level of investment may stem from the CEO’s overestimation of investments.

Managerial Overconfidence and Labor Investment Efficiency

Study aim to observe the impact of managerial overconfidence on labor investment. Malmendier Tate (2005) document the association between CEO overconfidence and the sensitivity of corporate investment to cash flow and find that overconfident managers overinve st in the presence of sufficient internal funds while reduc ing investment more sharply when external financing is necessary. Thus, managerial overconfidence is found to be related to inefficient corporate investment.

Compared with physical capital investme nt, labor investment has not attracted considerable attention among researchers , as standard neoclassical economics do not relate labor to firm value (To bin 1969; Tobin Brainard 1977). Rather, c lassical labor economics has traditionally considered labor to be a purely variable factor, adjusted exactly with the production output, whereas capital is treated as a purely fixed factor. This simplified Marshallian microeconomics model has received considerable criticism as it fails to incorporate various pheno mena in reality (Oi 1962; Oi 1983; Merz Yashiv 2007). To address such criticism , Oi (1962) claim s that labor is a quasi fixed factor, arguing that both labor a nd capital investments include a certain proportion of fixed costs. The fixed costs of labor mainly come from adjustments costs relat ed to hiring, training , and firing employees (Oi 1983; Farmer 1985; Hamermesh 1996).

Investment in labor , as a part of overall corporate investment, is different from physical capital investment in that the expected benefit from labor investment is more difficult to measure than that from physical capital investment (Schultz 1961; Weisbrod 1961). Typical p hysical capital investments are implemented by purchasing tangible assets or incurring R&D expenditures and facilitating the observation of cash inflow s, while the direct cash inflow is more difficult to observe for labor investments. This difficulty in ca lculating the expected net present value (NPV) can arise either from the difficult process of quantifying labor ’s economic contribution (Ashton Green 1996; Wolf 2002) or from the innate information asymmetry between employer s and employee s in the labor market (Stigler 1962). Either way, as an observable and tangible prediction of future cash inflow is more difficult for labor investment; the decision to invest in labor depends more heavily on manager s ’ discretion.

The study ma d e predictions regarding the impact of managerial overconfidence on labor investment efficiency based on this background. Research hypothesize d that managerial overconfidence increases labor investment , as managers’ overestimation of their own abilities and the firm’s prospects le ads to overinvestment in labor . H owever, managerial overconfidence can either improve or worsen labor investment efficiency, depending upon the firm’s level of overinvestment or underinvestment in labor . Under labor overinvestment, further investment in la bor induced by an overconfident CEO is expected to worsen labor investment efficiency while under labor underinvestment, the same decision reduces the deviation of labor investment from its optimal level and improves labor investment efficiency. Therefore, with research hypothesis Authors predict ed two directions regarding the association between managerial overconfidence and labor investment efficiency: a negative relation between CEO overconfidence and labor investment e fficiency for the firms that have already excessively invested in labor and a positive relation for the firms facing a shortage of labor and needing further investments to reach the optimal level. Overall, research develops following hypothesis:

H1: CEO ov erconfidence has effect on labor investment efficiency.

Research Design

Specification of Labor Investment Efficiency

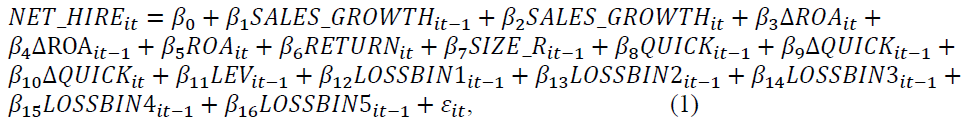

Following Pinnuck Lillis (2007), Li (2011), and Jung et al. (2014), the study estimate s labor investment inefficiency by calculating the difference between predicted (or optimal) labor investment and actual labor investment. As in the prior literature, the change in the number of employees is used as a proxy for the firm’s labor investment. This m easure of net hiring is regressed on a set of economic and corporate factors to produce the fitted or predicted net hiring level as shown in equation (1).

where NET_HIRE = the percentage change in employees; SALES_GROWTH = the percentage change in sales revenue; ROA = net income scaled by total assets at the beginning of the year; RETURN = the annual stock return for year t ; SIZE_R = the log of market value of equity at the beginning of the year, ranked into percentiles; QUICK = the ratio of cash and short term investments plus receivables to current liabilities; LEV = the ratio of long term debt to total assets at the beginning of the year; and the LOSSBIN variables are indicators for each 0.005 interval of the prior year ROA from 0 to 0.025 (i.e. LOSSBIN1 equals 1 if prior year ROA is between 0.005 and 0, LOSSBIN2 equals 1 if prior year ROA is between 0.010 and 0.005, and so on). The equation also includes industry fixed effects. All variables are listed in the Appendix.

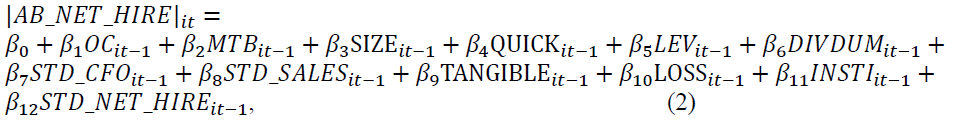

The research labor investment inefficiency measure is now computed as the absolute difference between the actual change in the number of employ ees and the expected net hiring calculated from regression equation (1). This absolute abnormal net hiring measure, |AB_NET_HIRE |, shows the firm’s distance from its optimal labor investment level.

Specification of Managerial Overconfidence

Research follow s Malmendier Tate (2005) and Campbell et al. (2011) in measur ing CEO overconfidence. They utilized the CEO’s net stock purchases and stock option holding s and exercising decisions to proxy for CEO overconfidence. Based on prior studies, authors denote d the CEO overconfidence variable (OC) as equal to 1 if CEOs hold stock options with a stock price that exceed s the exercise price by more than 100 %%. To determine whether CEOs hold stock options that are higher than 100 in the money, study require d that the CEO shows option holding behavior more than once during the sample period. The option moneyness is calculated as specified in Campbell et al. (2011).

Control Variables

Control variables are added in equation (2) below based on prior labor investment related studies, such as Biddle Hilary (2006) and Biddle , Hilary, Verdi (2009). The controls are growth options (MTBit-1), firm size (SIZEit-1), liquidity (QUICKit-1), leverage (LEVit-1), dividend payout (DIVDUMit-1), cash flow and sales volatilities (STD_CFOit-1, STD_SALESit-1), as these variables are expec ted to affect net hiring, or labor investment. Fo llowing Cella (2009), the proportion of outstanding shares held by institutions (INSITIit-1) is also included in this study regression analysis to capture the influence of institutional investors’ moni toring role on corporate employment decision s The research analyze the effects of managerial overconfidence on labor investment efficiency using ordinary least square (OLS) regression All these factors are included in this research the main regression equation as shown below.

w here OC = 1 if CEOs hold stock options with a stock price exceed ing the exercise price by more than 100 and 0 otherwise; MTB = the ratio of market value to book value of common equity at the beginning of the year; SIZE = the log of market value of equity at the beginning of the year; DIVDUM = 1 if the firm pays dividends in the previous year and 0 otherwise; STD_CFO = the standard deviation of cash flow fr om operations over years t−5 to t−1; STD_SALES = the standard deviation of sales revenue over years t−5 to t−1; TANGIBLE = the ratio of property, plant, and equipment (PPE) to total assets at the beginning of the year; LOSS = 1 if the firm reported a loss in the previous year and 0 otherwise; INSTI = the proportion of outstanding common shares held by institutions at the end of year t−1; STD_NET_HIRE = the standard deviation of the percentage change in employees over years t−5 to t−1; and all other variable s are as previously defined. The model includes industry and year dummy variables, and all standard errors are corrected for firm level clustering.

The study regress es authors main dependent variable of labor investment inefficiency, or absolute abnormal net hiring (|AB_NET_HIRE|), on this research primary independent variable, CEO overconfidence (OCit-1) and the control variables. If managerial overconfidence leads the firm to deviate more from optimal labor investment, the coefficient of OC (β1) is expected to be significantly positive. In contrast, a significantly negative coefficient of OC (β1) implies that CEO overconfidence helps the firm reach the optimal labor investment level.

Sample

Research obtain ed data on CEO option holdings from the ExecuComp database to calculate CEO overconfidence (OC). Most of the research other variables, such as the number of employees and variables on firm characteristics are obtained from Compustat and the Center for Research in Sec urity Prices (CRSP) databases. Institutional ownership data are obtained from Thomson Reuters’ CDA/Spectrum database.

The final sample co nsists of 72,059 firm year observations ranging from 1992 to 2015 reduced from the study initial sample due to the availability of many explanatory variables . The study b egins the sample in 1992 because ExecuComp provides data on manager s ’ stock option holdings from 1992.

Estimation of Abnormal Net Hiring

To estimated research labor investme nt inefficiency measure, research regress es the actual net hiring on a set of firm characteristic variables , as demonstrated in equation (1). Summary statistics for the variables used in equation (1) are shown in Panel A of Table 1. The r esults of the regression analysis performed on these variables are shown in Panel B of Table 1. Panel B reports results consistent with Pinnuck Lillis’s (2007) results. The estimated coefficient of SALES_GROWTHit is 0.324, which is similar to the value o f 0.330 reported by Pinnuck Lillis (2007), and all five coefficients of LOSSBIN are negative, three of which are significant at 5 level, which is also consistent with Pinnuck Lillis’s (2007) estimation. The study take s the absolute value of th e residuals from (1) to compute the study absolute abnormal net hiring (|AB_NET_HIRE|) variable and the raw value of the residuals from (1) to obtain the raw abnormal net hiring (AB_NET_HIRE) variable.

| Table 1 Estimation of the Expected Level of Net Hiring and Abnormal Hiring | |||||||||

| Panel A: Descriptive statistics for variables in model (1) | |||||||||

| Variables | N | Mean | Median | Std. dev. | Q1 | Q3 | |||

| NET_HIREit | 72,059 | 0.0855 | 0.0302 | 0.3170 | –0.0426 | 0.1429 | |||

| SALES_GROWTHit-1 | 72,059 | 0.2222 | 0.0894 | 0.6969 | –0.0150 | 0.2460 | |||

| SALES_GROWTHit | 72,059 | 0.1566 | 0.0794 | 0.4602 | –0.0234 | 0.2207 | |||

| ?ROAit-1 | 72,059 | 0.0642 | –0.1604 | 5.6850 | –0.8255 | 0.2746 | |||

| ?ROAit | 72,059 | –0.1831 | –0.1502 | 4.2307 | –0.7956 | 0.2731 | |||

| ROAit | 72,059 | 0.0018 | 0.0393 | 0.1923 | –0.0219 | 0.0894 | |||

| RETURNit | 72,059 | 0.1526 | 0.0684 | 0.6075 | –0.2108 | 0.3690 | |||

| SIZE_Rit-1 | 72,059 | 0.6477 | 0.7000 | 0.2540 | 0.4600 | 0.8700 | |||

| Quickit-1 | 72,059 | 2.2027 | 1.2839 | 4.0460 | 0.7924 | 2.3204 | |||

| ?Quickit-1 | 72,059 | 0.1781 | –0.0009 | 0.9011 | –0.1982 | 0.2343 | |||

| ?Quicktit | 72,059 | 0.0926 | –0.0127 | 0.6353 | –0.2067 | 0.2015 | |||

| LEVit-1 | 72,059 | 0.2098 | 0.1746 | 0.2013 | 0.0182 | 0.3349 | |||

| Panel B: Regression results (dependent variable = NET_HIRE) | |||||||||

| Independent variables | Predicted sign | Coefficient | (t-value) | ||||||

| Intercept | +/– | –0.044 | (–3.24) *** | ||||||

| SALES_GROWTHit-1 | + | 0.019 | (12.44) *** | ||||||

| SALES_GROWTHit | + | 0.324 | (142.48) *** | ||||||

| ?ROAit-1 | + | 0.001 | (5.57) *** | ||||||

| ?ROAit | – | 0.001 | (3.94) *** | ||||||

| ROAit | + | 0.102 | (18.02) *** | ||||||

| RETURNit | + | –0.005 | (–2.93) *** | ||||||

| SIZE_Rit-1 | + | 0.024 | (5.63) *** | ||||||

| Quickit-1 | + | 0.001 | (5.29) *** | ||||||

| ?Quickit-1 | + | 0.027 | (23.32) *** | ||||||

| ?Quicktit | +/– | –0.024 | (–14.92) *** | ||||||

| LEVit-1 | +/– | –0.069 | (–12.14) *** | ||||||

| LOSSBIN1it-1 | – | –0.023 | (–2.51) ** | ||||||

| LOSSBIN2it-1 | – | –0.034 | (–3.62) *** | ||||||

| LOSSBIN3it-1 | – | –0.030 | (–3.04) *** | ||||||

| LOSSBIN4it-1 | – | –0.010 | (–1.04) | ||||||

| LOSSBIN5it-1 | – | –0.013 | (–1.19) | ||||||

| Industry fixed effects | Yes | ||||||||

| [F-value] | [304.87] *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.267 | ||||||||

| N | 72,059 | ||||||||

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Univariate Results

Summary statist ics for the variables in the study main regression equation (2) are displayed in Table 2. Researcher’s main dependent variable, abnormal net hiring has a mean value of 0.1133 and a median value of 0.0687. Researcher’s main explanatory variable, CEO overcon fidence, has a mean value of 0.2672, which indicates that about 26.72 of managers in research sample are overconfident managers according to study definition of managerial overconfidence .

| Table 2 Descriptive Statistics for Variables in the Abnormal Net Hiring Model (Model 2) | |||||

| Variables | Mean | Median | Std. | Q1 | Q3 |

| |AB_NET_HIRE|it | 0.1133 | 0.0687 | 0.1525 | 0.0328 | 0.1307 |

| AB_NET_HIREit | –0.0072 | –0.0311 | 0.1864 | –0.0865 | 0.0364 |

| OC it-1 | 0.2672 | 0.0000 | 0.4425 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| MTB it-1 | 3.8521 | 2.3374 | 62.8056 | 1.4963 | 3.7530 |

| SIZE it-1 | 7.2100 | 7.0391 | 1.6635 | 6.0467 | 8.2683 |

| Quick it-1 | 1.8150 | 1.2597 | 2.0284 | 0.8146 | 2.0518 |

| LEV it-1 | 0.2117 | 0.1917 | 0.2068 | 0.0388 | 0.3174 |

| DIVDUM it-1 | 0.4523 | 0.0000 | 0.4977 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

| STD_CFO it-1 | 171.682 | 42.213 | 549.628 | 16.762 | 122.562 |

| STD_SALE it-1 | 906.758 | 188.685 | 3451.520 | 69.324 | 565.215 |

| TANGIBLE it-1 | 0.2760 | 0.2097 | 0.2212 | 0.1042 | 0.3906 |

| LOSS it-1 | 0.1769 | 0.0000 | 0.3816 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| INSTI it-1 | 0.7875 | 0.8513 | 0.2229 | 0.6706 | 0.9881 |

| STD_NET_HIRE it-1 | 0.2013 | 0.1188 | 0.3272 | 0.0661 | 0.2231 |

Table 3 shows correlation coefficients for the study variables. Both Pearson’s raw and Spearman’s rank order correlation coefficients are presented. Authors observe d significantly positive correlation coefficients between absolute abnormal net hiring (|AB_NET_HIRE|) and CEO overconfidence (OC) using both Pearson’s (0.066) a nd Spearman’s (0.024) methods. T herefore determine t hat the univariate analysis implies that managerial overconfidence increases the deviation from optimal labor investment and impairs labor investment efficiency. The correlation coefficient between raw abnormal net hiring (AB_NET_HIRE) and CEO over confidence (OC) is also significantly positive using both Pearson’s (0.121) and Spearman’s (0.141) methods. This supp orts the hypothesis that managerial over confidence is positively related to labor investment

| Table 3 Correlations | |||||||||||||||

| # | Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 1 | |AB_NET_HIRE| | 0.465 | 0.066 | 0.001 | -0.124 | 0.114 | -0.023 | -0.117 | -0.030 | -0.016 | -0.023 | 0.085 | -0.099 | 0.145 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.897) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.008) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.063) | (0.007) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| 2 | AB_NET_HIRE | -0.209 | 0.121 | -0.009 | -0.029 | 0.061 | -0.036 | -0.075 | -0.029 | -0.019 | -0.031 | -0.080 | -0.009 | 0.030 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.305) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.024) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.320) | (0.000) | |||

| 3 | OC | 0.024 | 0.141 | 0.028 | 0.005 | 0.045 | -0.056 | -0.131 | -0.049 | -0.033 | -0.055 | -0.118 | -0.009 | 0.035 | |

| (0.006) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.594) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.302) | (0.000) | |||

| 4 | MTB | -0.034 | 0.116 | 0.257 | 0.021 | -0.002 | 0.017 | 0.001 | 0.002 | -0.002 | -0.012 | -0.017 | 0.003 | -0.008 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.016) | (0.784) | (0.048) | (0.916) | (0.787) | (0.838) | (0.167) | (0.052) | (0.751) | (0.376) | |||

| 5 | SIZE | -0.139 | -0.007 | 0.009 | 0.397 | -0.147 | 0.064 | 0.351 | 0.398 | 0.325 | 0.043 | -0.285 | 0.250 | -0.130 | |

| (0.000) | (0.424) | (0.294) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| 6 | Quick | 0.095 | 0.047 | 0.058 | 0.071 | -0.178 | -0.257 | -0.208 | -0.075 | -0.080 | -0.250 | 0.054 | -0.022 | 0.040 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.010) | (0.000) | |||

| 7 | LEV | -0.047 | -0.026 | -0.081 | -0.113 | 0.136 | -0.444 | 0.084 | 0.039 | 0.018 | 0.228 | 0.086 | -0.017 | 0.028 | |

| (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.033) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.043) | (0.001) | |||

| 8 | DIVDUM | -0.124 | -0.074 | -0.131 | 0.031 | 0.337 | -0.254 | 0.154 | 0.142 | 0.123 | 0.159 | -0.196 | -0.032 | -0.172 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| 9 | STD_CFO | -0.087 | -0.057 | -0.077 | 0.071 | 0.756 | -0.273 | 0.263 | 0.255 | 0.715 | 0.084 | -0.030 | -0.035 | -0.027 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.002) | |||

| 10 | STD_SALE | -0.077 | -0.030 | -0.041 | 0.072 | 0.691 | -0.339 | 0.270 | 0.259 | 0.819 | 0.066 | -0.037 | -0.032 | 0.015 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.081) | |||

| 11 | TANGIBLE | -0.035 | -0.024 | -0.062 | -0.137 | 0.044 | -0.381 | 0.298 | 0.208 | 0.131 | 0.118 | -0.009 | -0.108 | -0.015 | |

| (0.000) | (0.005) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.317) | (0.000) | (0.089) | |||

| 12 | LOSS | 0.111 | -0.096 | -0.118 | -0.200 | -0.284 | 0.022 | 0.068 | -0.196 | -0.075 | -0.128 | -0.018 | -0.136 | 0.095 | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.012) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.040) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| 13 | INSTI | -0.062 | 0.005 | -0.003 | 0.032 | 0.219 | 0.064 | -0.016 | -0.109 | 0.153 | 0.129 | -0.143 | -0.105 | -0.055 | |

| (0.000) | (0.565) | (0.746) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.070) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

| 14 | STD_NET_HIRE | 0.202 | 0.027 | 0.047 | -0.071 | -0.250 | 0.125 | -0.009 | -0.300 | -0.143 | -0.053 | -0.117 | 0.178 | -0.051 | |

| (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.296) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||

Main Regression Results

Table 4 reports the empirical analysis results of equation (2). The first three columns show analyses with absolute abnormal net hiring (|AB_NET_HIRE|) as the dependent variable. The first column shows regression results using the full sample, and authors found a significantly positive coefficient for CEO overconfidence (OC). This i ndicate s that managerial overconfidence worsens the firm’s labor investment efficiency, imply ing that overconfidence leads manager s to engage in more labor investment than the optimal investment level. When the study further observes the results in the second and thir d columns, authors found that the relationship between CEO overconfidence and labor investment efficiency differs between the labor overin vestment and underinvestment observations. The second column shows the results from analy zing a subsample with actual net hiring exceeding the predicted (or optimal) net hiring, and the third column shows the results from analy zing a subsample with actual net hiring under the predicted (or optimal) net hiring . In other words, the second and third columns display the results of analyses performed for subsamples of overinvestment and underinvestment in labor , respectively. For the labor overinvestment subsamp le, the study still observe a significantly positive coefficient for OC, but the significantly positive association between managerial overconfidence and labor investment inefficiency disappears in the third column that is, for the labor underinvestment subsample. The researchers can interpret this finding to indicate that overconfident CEOs decrease labor investment efficiency given labor overinvestment , but there is no significant relationship if the firm has underinvested in labor The fourth column uses the raw difference between actual net hiring and optimal net hiring as the dependent variable. This dependent variable has a positive value for overinvestment in labor and a negative value for underinvestment in labor . The results in the fourth column imply that CEO overconfidence has a tendency to increas e the firm’s net hiring for the entire sample . Research results exten d the findings of Malmendier Tate (2005) that the managerial overconfidence is related to inefficient investment . Overall , we can summarize that managerial overconfidence increases labor investment, especially when labor overinvestment is present , and this worsens labor investment efficiency.

| Table 4 Effect of Managerial Overconfidence on Abnormal Net Hiring? | ||||

| Dependent variable: | ||||

| |AB_NET_HIRE| | |AB_NET_HIRE| | |AB_NET_HIRE| | AB_NET_HIRE | |

| Full sample | AB_NET_HIRE > 0 | AB_NET_HIRE < 0 | Full sample | |

| Independent variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Intercept | 0.1274*** | 0.1576*** | 0.0885*** | 0.0722*** |

| (6.13) | (4.41) | (5.84) | (3.13) | |

| OC | 0.0169*** | 0.0264*** | 0.0004 | 0.0396*** |

| (4.63) | (3.88) | (0.14) | (9.82) | |

| MTB | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001*** | 0.0001*** |

| (0.89) | (–0.57) | (3.55) | (–4.03) | |

| SIZE | –0.0044*** | –0.0052** | –0.0036*** | –0.0016 |

| (–4.17) | (–2.19) | (–4.20) | (–1.29) | |

| Quick | 0.0061*** | 0.0102*** | 0.0034*** | 0.0036** |

| (4.94) | (5.48) | (3.96) | (2.21) | |

| LEV | –0.0067 | –0.0051 | –0.0037 | –0.0027 |

| (–0.83) | (–0.30) | (–0.61) | (–0.31) | |

| DIVDUM | –0.0155*** | 0.0221*** | –0.0047* | –0.0288*** |

| (–4.86) | (–3.06) | (–1.87) | (–7.90) | |

| STD_CFO | –0.0001 | –0.0001* | 0.0000 | –0.0001 |

| (–0.27) | (–1.66) | (0.68) | (–0.65) | |

| STD_SALE | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| (0.91) | (0.49) | (0.91) | (0.05) | |

| TANGIBLE | –0.0538*** | –0.0854*** | –0.0333*** | –0.0231* |

| (–4.55) | (–3.35) | (–3.62) | (–1.87) | |

| LOSS | 0.0179*** | –0.0094 | 0.0359*** | –0.0441*** |

| (4.52) | (–1.02) | (9.79) | (–9.19) | |

| INSTI | –0.0235** | –0.0237 | –0.0265*** | 0.0128 |

| (–2.54) | (–1.27) | (–3.57) | (1.20) | |

| STD_NET_HIRE | 0.0451*** | 0.0562*** | 0.0345*** | 0.0083 |

| (6.55) | (4.56) | (5.45) | (1.27) | |

| Year-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [F-value] | [26.06] *** | [11.47] *** | [92.30] *** | [12.07] *** |

| R2 | 0.080 | 0.093 | 0.113 | 0.044 |

| N | 13,597 | 4,896 | 8,701 | 13,597 |

Subsample Analysis

The research labor overinvestment sub sample AB_NET_HIRE > is now further decomposed into two more subsamples overhiring and underfiring subsamples. The o verhiring subsample includes observations with positive AB_NET_HIRE values and positive expected net hiring ( ?) values. This subsample contains labor overinvestment observations with a positive opti mal labor investment level or overhiring. Likewise, the underfiring subsample comprises observations with positive AB_NET_HIRE values and negative expected net hiring (

?) values. This subsample contains labor overinvestment observations with a positive opti mal labor investment level or overhiring. Likewise, the underfiring subsample comprises observations with positive AB_NET_HIRE values and negative expected net hiring ( ) values. This subsample indicates overinvestment when the optimal labor level is negative, representing the condition of underfiring.

) values. This subsample indicates overinvestment when the optimal labor level is negative, representing the condition of underfiring.

Table 5 presents the results of the subsample analysis. Each column shows the results for the overhiring and underfiring subsamples. For the overhiring subsample, we find a significantly posit ive coefficient for OC, and for the underfiring subsample, we observe a significantly negative coefficient. The results from both columns consistently indicate that overconfidence induces CEO s to invest more in labor for both cases of labor overinvestment. Therefore, in the overhiring situation, CEO overconfidence increases labor inefficiency, but in the underfiring situation, CEO overconfidence improves labor investment efficiency. Additionally, the result s in these two columns imply that i f labor overinvestment exists , CEO overconfidence increases labor investment inefficiency only for the overhiring subsample and decreases labor investment inefficiency for the underfiring subsample , even though managerial overconfidence was uniformly shown to increase investment inefficiency in the second column of Table 4.

| Table 5 Effect of Managerial Overconfidence on Overhiring and Underfiring | |||

| Dependent variable: |AB_NET_HIRE| | |||

| Overhiring | Underhiring | ||

| Independent variables | (1) | (2) | |

| Intercept | 0.1756*** | 0.0787*** | |

| (4.91) | (2.63) | ||

| OC | 0.0246*** | –0.0207** | |

| (3.55) | (–2.32) | ||

| MTB | –0.0001 | –0.0002*** | |

| (–0.58) | (–2.80) | ||

| SIZE | –0.0062** | 0.0011 | |

| (–2.49) | (0.53) | ||

| Quick | 0.0099*** | –0.0011 | |

| (5.25) | (–0.55) | ||

| LEV | 0.0001 | –0.0011 | |

| (0.01) | (–0.09) | ||

| DIVDUM | –0.0214*** | –0.0132** | |

| (–2.83) | (–2.27) | ||

| STD_CFO | –0.0001 | –0.0001 | |

| (–1.56) | (–0.01) | ||

| STD_SALE | 0.0001 | 0.0001** | |

| (0.41) | (2.07) | ||

| TANGIBLE | –0.0883*** | –0.0380** | |

| (–3.28) | (–2.10) | ||

| LOSS | –0.0022 | 0.0099* | |

| (–0.22) | (1.87) | ||

| INSTI | –0.0224 | –0.0398** | |

| (–1.15) | (–1.99) | ||

| STD_NET_HIRE | 0.0558*** | 0.0240 | |

| (4.49) | (1.35) | ||

| Year-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | |

| Industry-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | |

| [F-value] | [13.07] *** | [4.76] *** | |

| R2 | 0.091 | 0.321 | |

| N | 4,671 | 322 | |

Effect of Cash flow on Research Hypothesized Relationships

We additionally examine the impact of cash flow on the association between managerial overconfidence and labor investment following Malmendier Tate (2005). The se authors empirically show tha t overconfident CEOs tend to overinvest in the presence of sufficient internal funds, while they reduce investments in external funds. This increase in the sensitivity of investment to cash flow is driven by both the difference between manager s ’ and shareholders’ interests (Jensen Meckling 1976; Jensen 1986) and the asymmetric information between manager s and the outside capital market (Myers Majluf 1984). O verconfident managers perceive external financing to be expensive because they predict a very positive future, which induces them to use internal capital for investments.

To empirically investigate the association between overconfidence and investment cash flow sensitivity, we first measure in ternal capital , or Cashflow by earnings before extraordinary items plus depreciation , and we normalize the measure by capital at the beginning of the year. We insert this variable (Cashflow) and its interaction with overconfidence (OC*Cashflow) in the main regression equation and observe the coefficient of the interaction term. As we hypothesize that labor investment decision s depend more heavily on managerial discretion, we expect that overconfidence magnifies the sensitivity of labor investment to cash flow, consistent with Malmendier Tate’s (2005) results.

Table 6 displays the impact of cash flow on the research hypothesized relationship. As shown in Table 4, columns (1) through (3) use |AB_NET_HIRE| as the dependent variable, while column (4) uses AB_NET_HIRE as the dependent variable. W e find significantly positive coefficients for Cashflow and OC*Cashflow in al l the analyses presented in columns (1) to (3), which implies that internal funds tend to decrease labor investment efficiency and that managerial overconfidence enlarges such a tendency for both the labor overinvestment and underinvestment subsamples. The fourth column , with AB_NET_HIRE as the dependent variable , also shows significantly pos itive coefficients for all these variab les, Cashflow and OC*Cashflow . Thus, we observe that both managerial overconfidence and internal funds lead to more investments in net hiring, and CEO overconfidence increases the sensitivity of labor investment to cashflow. Overall , however, as column (3) shows, in the presence of labor underinvestment, cashflow decreases labor investment even more , and overconfidence deepens the negative impact of cashflow on labor investment. Hence, we can conclude that, overall , internal funds worsen labor investment efficiency, and managerial overconfidence increases the negative influence of internal funds on labor investment efficiency. These overall results are consistent with Malmendier Tate’s (2005) empirical findings.

| Table 6 Effect of Cashflow on Research Hypothesized Relationship | ||||

| Dependent variable: | ||||

| |AB_NET_HIRE| | |AB_NET_HIRE| | |AB_NET_HIRE| | AB_NET_HIRE | |

| Full sample | AB_NET_HIRE > 0 | AB_NET_HIRE < 0 | Full sample | |

| Independent variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Intercept | 0.1281*** | 0.1572*** | 0.0871*** | 0.0750*** |

| (6.04) | (4.61) | (5.65) | (3.26) | |

| OC | 0.0144** | 0.0466*** | 0.0107* | 0.0492*** |

| (2.27) | (4.03) | (1.86) | (6.78) | |

| Cashflow | 0.0011* | 0.0196** | 0.0090*** | 0.0190*** |

| (1.68) | (2.56) | (3.61) | (4.96) | |

| OC*Cashflow | 0.0005* | 0.0359** | 0.0115* | 0.0207** |

| (1.68) | (2.53) | (1.80) | (2.43) | |

| MTB | 0.0001 | -0.0001 | -0.0001*** | -0.0001*** |

| (0.96) | (-0.56) | (3.57) | (-4.14) | |

| SIZE | -0.0045*** | -0.0059** | -0.0030*** | -0.0025** |

| (-4.17) | (-2.41) | (-3.48) | (-2.03) | |

| Quick | 0.0057*** | 0.0101*** | 0.0034*** | 0.0035** |

| (4.55) | (5.45) | (3.84) | (2.17) | |

| LEV | -0.0035 | -0.0041 | -0.0069 | 0.0003 |

| (-0.42) | (-0.24) | (-1.10) | (0.04) | |

| DIVDUM | -0.0147*** | -0.0228*** | -0.0046* | -0.0293*** |

| (-4.57) | (-3.17) | (-1.83) | (-8.06) | |

| STD_CFO | -0.0001 | -0.0001 | -0.0001 | -0.0001 |

| (-0.33) | (-1.61) | (0.55) | (-0.54) | |

| STD_SALE | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| (0.94) | (0.46) | (0.76) | (0.11) | |

| TANGIBLE | -0.0528*** | -0.0879*** | -0.0277*** | -0.0294** |

| (-4.45) | (-3.35) | (-2.99) | (-2.35) | |

| LOSS | 0.0177*** | -0.0061 | 0.0332*** | -0.0404*** |

| (4.46) | (-0.66) | (8.94) | (-8.29) | |

| INSTI | -0.0237*** | -0.0221 | -0.0276*** | 0.0140 |

| (-2.54) | (-1.18) | (-3.69) | (1.32) | |

| STD_NET_HIRE | 0.0452*** | 0.0561*** | 0.0339*** | 0.0086 |

| (6.56) | (4.56) | (5.44) | (1.32) | |

| Year-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [F-value] | [25.41] *** | [10.68] *** | [1116.32] *** | [13.94] *** |

| R2 | 0.081 | 0.095 | 0.116 | 0.045 |

| N | 13,498 | 4,886 | 8,693 | 13,498 |

Note: This table presents the regression results of examining the moderate effect of cashflows on research hypothesized relationship between abnormal net hiring ( (|AB_NET_HIRE| or AB_NET_HIRE) and managerial overconfidence (OC). The t statistics are reported in parentheses. Models (1), (2), and (3) use the absolute value of abnormal net hiring ( (|AB_NET_HIRE|) as the dependent variable, and Model 4 uses signed abnormal net hiring AB_NET_HIRE) as the dependent variable. Models (1) and (4) test the full sample, and Models (2) and (3) test two different subsamples with positive and negative abnormal net hiring, respectively. The t statistics are reported in parentheses. The F value is reported in square brackets. The definitions of the variables are presented in tge Appendix. ***, **, and * indicate statistical significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Robustness Test

We follow Campbell et al. 2011) in conduct ing a false test. We construct a low optimism measure for manager s , the opposite of a man a ger’s high optimism or CEO overconfidence. Following Campbell et al. (2011), a low optimi sm CEO is defined as one who exercises stock options that are less than 30 in t he money and who does not hold options that are exercisable and greater than 30 in the money. Similar to research computation of the CEO’s high optimism measure, one is also required to exercise stock options that are less than 30 in the money at least t wice in the sample period for the low optimism measure. If the CEO shows low optimi sm , the study dummy variable (LC) equals 1 and 0 otherwise.

T hen regress es reserch labor investment inefficiency measure, absolute abnormal net hiring (|AB_NET_HIRE|), on the CEO Low optimism measure (LC) and other control variables as in equation (2). Research expect ed opposite results for the coefficient of LC compared with the coefficients of OC . Table 7 displays the study false test results.

| Table 7 False Test? | ||||

| Dependent variable | ||||

| |AB_NET_HIRE| | |AB_NET_HIRE| | |AB_NET_HIRE| | AB_NET_HIRE | |

| Full sample | AB_NET_HIRE > 0 | AB_NET_HIRE < 0 | Full sample | |

| Independent variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| Intercept | 0.1353*** | 0.1685*** | 0.0854*** | 0.1068*** |

| (6.62) | (4.66) | (5.56) | (4.48) | |

| LC | -0.0051* | -0.0092 | 0.0033 | -0.0292*** |

| (-1.77) | (-1.32) | (1.44) | (-8.58) | |

| MTB | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001*** | -0.0001*** |

| (1.25) | (-0.36) | (3.57) | (-3.82) | |

| SIZE | -0.0044*** | -0.0048** | -0.0034*** | -0.0023* |

| (-4.10) | (-2.02) | (-3.93) | (-1.88) | |

| Quick | 0.0062*** | 0.0100*** | 0.0034*** | 0.0036** |

| (4.95) | (5.40) | (3.97) | (2.25) | |

| LEV | -0.0076 | -0.0070 | -0.0039 | -0.0039 |

| (-0.94) | (-0.41) | (-0.65) | (-0.45) | |

| DIVDUM | -0.0175*** | -0.0257*** | -0.0050** | -0.0321*** |

| (-5.45) | (-3.56) | (-2.00) | (-8.81) | |

| STD_CFO | -0.0001 | -0.0001* | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| (-0.36) | (-1.74) | (0.56) | (-0.50) | |

| STD_SALE | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | -0.0001 |

| (0.80) | (0.40) | (0.94) | (-0.29) | |

| TANGIBLE | -0.0549*** | -0.0894*** | -0.0335*** | -0.0241* |

| (-4.61) | (-3.48) | (-3.62) | (-1.94) | |

| LOSS | 0.0166 | -0.0111 | 0.0350*** | -0.0434*** |

| (4.10) | (-1.18) | (9.44) | (-8.90) | |

| INSTI | -0.0243*** | -0.0263 | -0.0266*** | 0.0112 |

| (-2.61) | (-1.42) | (-3.57) | (1.06) | |

| STD_NET_HIRE | 0.0454*** | 0.0564*** | 0.0345*** | 0.0092 |

| (6.53) | (4.53) | (5.45) | (1.39) | |

| Year-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry-fixed effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [F-value] | [26.38] *** | [16.45] *** | [66.83] *** | [11.17] *** |

| R2 | 0.078 | 0.090 | 0.114 | 0.041 |

| N | 13,597 | 4,896 | 8,701 | 13,597 |

As expected, the first column with the full sample shows a significantly negative coefficient for CEO low optimism (LC), but the second and third columns with the labor overinvestment and underinvestment subsamples , respectively, do not show significant co efficients for LC. The fourth column with raw abnormal net hiring (AB_NET_HIRE) as the dependent variable also shows a significantly negative coefficient for LC. Thus, low optimi sm CEOs are shown to decrease labor investment and increase labor investment efficiency on average. The study false test mostly strengthens the main regression results.

Conclusion

The study investigated the association between managerial overconfidence and labor investment efficiency. Research hypothesized that managerial overconfidence leads to higher investment in labor from overestim ation. The empirical analysis reveals that given labor overinvestment, managerial overconfidence in creases labor investment and decreases labor investment efficiency . Hence, CEO overconfidence affects labor investment efficiency differently according to the existence of labor overinvestment. Therefore , to examine the impact of managerial overconfidence, the asymmetric influence due to overinvestment or underinvestment in labor should be considered Managerial overconfidence of lar ge firms has a tendency to result in improved labor investment efficiency. Research conjecture is that this is due to the endogeneity problem. The proxies of managerial overconfidence and labor investment efficiency that author use in the study have room f or improvement in the ongoing research. Further analyses with additional subs amples, with cashflow and with a measure of CEO s ’ low optimism , all support and strengthen research hypothesis.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University Research Grants in 2019.

References

- Alicke, M.D. (1985). Global self-evaluation as determined by the desirability and controllability of trait adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(6), 1621-1630.

- Alicke, M.D., & Govorun, O. (2005). The better-than-average effect. The Self in Social Judgment, 1, 85-106.

- Ashton, D., & Green, F. (1996). Education, training and the global economy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bartlett, C.A., & Ghoshal, S. (2002). Building competitive advantage through people. MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(2), 34.

- Becker, B., & Gerhart. B. (1996). The impact of human resource management on organizational performance: progress and prospects. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 779-801.

- Bernanke, B.S. (2010). Opening remarks: The economic outlook and monetary policy. Proceedings-Economic Policy Symposium-Jackson Hole (pp. 1-16; Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City).

- Biddle, G.C., & Hilary, G. (2006). Accounting quality and firm-level capital investment. The Accounting Review,81(5), 963-982.

- Biddle, G.C., Hilary, G., & Verdi, R.S. (2009). How does financial reporting quality relate to investment efficiency? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48(2), 112-131.

- Camerer, C., & Lovallo, D. (1999). Overconfidence and excess entry: An experimental approach. The American Economic Review, 89(1), 306-318.

- Campbell, T.C., Gallmeyer, M., Johnson, S.A., Rutherford, J., & Stanley, B.W. (2011). CEO optimism and forced turnover. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(3), 695-712.

- Cella, C. (2009). Institutional investors and corporate investment. Unpublished working paper, Indiana University.

- Farmer, R.E. (1985). Implicit contracts with asymmetric information and bankruptcy: The effect of interest rates on layoffs. The Review of Economic Studies,52(3), 427-442.

- Franke, R.H. (1994). Competitive advantage through people: Unleashing the power of the work force. The Academy of Management Perspectives,8(2), 93.

- Gimeno, J., Folta, T.B., Cooper, A.C., & Woo, C.Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 750-783.

- Hamermesh, D.S. (1996). Labor Demand (Princeton University Press).

- Haynes, K.T., Hitt, M.A., & Campbell, J.T. (2015). The dark side of leadership: Towards a mid?range theory of hubris and greed in entrepreneurial contexts. Journal of Management Studies, 52(4), 479-505.

- Heaton, J.B. (2002). Managerial optimism and corporate finance. Financial Management, 33-45.

- Hiller, N.J., & Hambrick, D.C. (2005). Conceptualizing executive hubris: The role of (hyper?) core self?evaluations in strategic decision?making. Strategic Management Journal, 26(4), 297-319.

- Jensen, M.C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance and takeovers. American Economic Review,76, 323-329.

- Jensen, M.C., & Meckling, W. (1976). The theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305-360.

- Jung, B., Lee, W.J., & Weber, D.P. (2014). Financial reporting quality and labor investment efficiency. Contemporary Accounting Research,31(4), 1047-1076.

- Kidd, J.B. (1970). The utilization of subjective probabilities in production planning. Acta Psychologica, 34, 338-347.

- Kruger, J. (1999). Lake Wobegon be gone! The ‘below-average effect’ and the egocentric nature of comparative ability judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(2), 221.

- Lai, J.H., Lin, W.C., & Chen, L.Y. (2017). The influence of CEO overconfidence on ownership choice in foreign market entry decisions. International Business Review, 26(4), 774-785.

- Larwood, L., & Whittaker, W. (1977). Managerial myopia: Self-serving biases in organizational planning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 194.

- Li, F. (2011). Earnings quality based on corporate investment decisions. Journal of Accounting Research,49(3), 721-752.

- Malmendier, U., & Tate, G. (2005). CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance, 60(6), 2661-2700.

- Merz, M., & Yashiv, E. (2007). Labor and the market value of the firm. American Economic Review,97(4), 1419-1431.

- Miller, D.T., & Ross, M. (1975). Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction. Psychological Bulletin, 82(2), 213-225.

- Moore, P.G. (1977). The manager’s struggles with uncertainty. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 129-165.

- Myers, S.C., & Majluf, N.S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13(2), 187-221.

- Oi, W.Y., (1962). Labor as a Quasi-fixed Factor. Journal of Political Economy, 70(6), 538-555.

- Oi, W.Y., (1983). The fixed employment costs of specialized labor: The measurement of labor cost, 63-122; University of Chicago Press.

- Picone, P.M., G.B. Dagnino, & Minà, A. (2014). The origin of failure: A multidisciplinary appraisal of the hubris hypothesis and proposed research agenda. The Academy of Management Perspectives,28(4), 447-468.

- Pinnuck, M., & Lillis, A.M. (2007). Profits versus losses: does reporting an accounting loss act as a heuristic trigger to exercise the abandonment option and divest employees? The Accounting Review, 82(4), 1031-1053.

- Schultz, T.W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1-17.

- Stigler, G.J. (1962). Information in the labor market. Journal of political economy, 70 (5), 94-105.

- Svenson, O. (1981). Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica, 47(2), 143-148.

- Tobin, J. (1969). A general equilibrium approach to monetary theory. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking,1(1), 15-29.

- Tobin, J., & Brainard, W. (1977). Assets markets and the cost of capital. Economic Progress, Private Values and Public Policies: Essays in Honor of William Fellner, ed. B. Belassa and R. Nelson, pp. 235-62; Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company).

- Weisbrod, B.A. (1961). The valuation of human capital. Journal of Political Economy, 69(5), 425-436.

- Wolf, A. (2002). Does Education Matter? Myths about Education and Economic Growth. London: Penguin.