Research Article: 2021 Vol: 24 Issue: 1S

Meaningful Work as a Mechanism Linking Corporate Social Responsibility Participation and Helping Behavior: A Study of Hospitality Industry in Thailand

Boonthong Uahiranyanon, Southeast Asia University

Kanyamon Kanchanathaveekul, Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University

Jaruaypornpat Leesomsiri, Northern College

Tianchai Aramyok, Shinawatra University

Keywords

Helping Behaviour, Organisational Citizenship Behaviour, Generation Y, Hotels, Meaningful Work

Abstract

The current research aims to investigate the mediating role of meaningful work (MW) in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) participation and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB) relationship. This research is of significance due to three aspects: 1. the combined analysis of CSR, novelty of OCB and MW; the relative impacts of corporate social responsibility perception vs. corporate social responsibility participation has not been previously done; 2. Impact of corporate social responsibility participation and corporate social responsibility perception is new and 3. This is the first study that examines these relationships across employees of different generations. Data were collected from 250 respondents working in hotels (four star) in Krabi, Thailand. For analysis of data, Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique and multi-group analysis was used. According to the results, CSR participation strongly influences work related outcome. Corporate social responsibility participation effect is on helping behaviour (HB) is strongest in Generation Y (Gen Y); while in Generation X (Gen X), corporate social responsibility perceptions strongly and indirectly affects HB via MW. This study results provide managerial implications that will benefit the hotel by managing the difference in generations to predict HB at work.

Introduction

Nowadays, CSR particularly in the hospitality industry is becoming an integral part of businesses (Rhou, Kim, Uysal & Kwon, 2017). CSR is referred as “context specific organisational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectation and the triple bottom line of the economic, social, and environmental performance” (Glavas & Aguinis, 2012). In addition, employees are critical players involved in CSR activities that lead to performance of the organization and also enhances motivation and well-being among employees (Greenwood & Voegtlin, 2016). Nonetheless, according to Glavas & Aguinis, (2012), there is not much empirical evidence of the relationship between CSR and work-related performance. The current research therefore aims to examine the correlation between CSR and preferred organizational outcome by hotel staff. Farrukh, Sajid, Lee & Shahzad, (2020) argue that CSR initiatives could possibly have an impact on employees work behavior. Yet, studies that investigate this link focuses primarily on the perception of the CSR reputation of an organization (Li, Fu & Duan, 2014; Omar, Rupp & Farooq, 2017). Studies however show that most people do not possess much knowledge of the CSR practices of their organization (Gangi, Mustilli & Varrone, 2019). We thus, are unable to comprehend the participation of employees in CSR practices and whether this involvement fulfills their requirement for MW. Bhattacherya, Korschun & Sen, (2008) suggested “a major challenge for managers is to increase employees’ proximity to their CSR initiatives, taking them from unawareness to active involvement”. In particular, the current research is among the few studies in the hospitality sector to study the relationship between corporate social responsibility participation and work-related outcome. There has been inconsistency in findings of past studies between corporate social responsibility and OCB; some showed significant effects and some did not (Li et al., 2014).

Such inconsistencies explain complexity in the relationships and are likely to be affected by circumstances or/and mediation. Industries, for example, are having a hard time understanding the work values of different generations, particularly Gen X (born 1965–1980) and Gen Y or more commonly known as millennial (born 1981-2000) (Chi, Gursoy & Karadag, 2013). A number of work characteristics have been attributed to the millennial, like search for jobs that are challenging and that are of career significance. There is, however, a lack of studies on Generation Y’s work meaning, especially in the hospitality industry and how it affects the work outcome. Past research showed how the relationship between CSR and organizational outcome is mediated by MW (Blunschi & Raub, 2014).

Current research will thus help to better understand the function of MW as a mediator and how CSR practices contribute to the HB aspect of OCB. In the hospitality sector, HB is necessary. Qu and Ma (2011) suggest that the individuality of the hospitality products make it important to help colleagues. OCB has been modelled as a multi-dimensional variable in most of the studies that investigated CSR’s influence on OCB. The current research will explore HB as a single outcome construct of a specific hospitality setting. It has been predicted by “The World Travel and Tourism Council” (WTTC) that in the coming years, the hotel industry will be facing shortage in human capital (WTTC, 2015). Additionally, as per a survey by fifteen renowned hospitality companies, Generation Y accounts over 80 percent of today's workforce (Korn Ferry Institute, 2015). Thailand, among a few more countries, faces shortage of talent (WTTC, 2015). Rapid developments make it more difficult for hospitality managers to attract, motivate and retain skilled staff. The managers will be benefitted for the findings of this study in gaining competitive advantage and to understand the role of involvement in CSR in creating high-quality workplace and workforce. In order to fill the gaps identified in the literature of hospitality, the aim of the current research is determining: 1. more effective impacts of CSR can be established by the relationship between CSR and OCB via meaningful work; and 2. Does CSR influence MW and the essential organizational citizenship behavior of helping colleagues for the different generation of hotel staff. Therefore, this research would be the first to analyze these relationships and for Generation Y in particular.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

On the basis of the literature, the theoretical model of the current research concerns the firms’ internal consequences that conducts CSR practices (Johns, Donia, Raja & Khalil Ben Ayed, 2018; Omar et al., 2017). CSR is an activity related to the welfare of the wider community, such as the concerns of stakeholders on socio-cultural, environmental and ethical concerns (Glavas & Aguinis, 2012). CSR programs include philanthropy, job equity, preservation of the environment or restoration and conservation of heritage and culture. Theories such as psychological needs theory, causal attribution, signaling theory, organizational identity, social exchange theory and organizational justice (El Akremi, Gond, Swaen & Babu, 2017) collectively help explain why CSR activities will have a positive influence on employees. The social identity theory states that those employees prefer to express and share in the organization’s best interests whose belief and identification corresponds to the identity and belief of the organization (Ashforth & Mael, 1992). Whereas the theory of social exchange states that when employees are treated positively, as if they were provided with the support they require, they tend to perform better (Birtch, Chiang & Van Esch, 2016). According to the theory, employees perceive and interpret organisational activities and then utilize the information/knowledge to demonstrate their attitude and behaviours at work. Another source suggests a view based on justice where workers review relevant facts in order to judge the organization's fairness (Frenkel & Bednall, 2016). The majority of existing literature focuses on psychological needs, i.e. safety, belonging, security, social and security needs. In the current research, a generalized theoretical framework is adopted which assigns a positive work-related outcome corresponding to the accessibility of information on the CSR performance of the company (Omar et al., 2017). In addition, the framework also indicates that greater personal engagement and social interaction with CSR activities in the company would contribute to a greater tendency for OCB to reciprocate.

Relationship between CSR and OCB

Significant evidence has been provided to date that corporate social responsibility could have a positive effect on desirable outcomes at the workplace, like organizational identification, organizational commitment, job performance, turnover intention and organizational citizenship behaviour (Song, Kim & Lee, 2016; Jermsittiparsert, Siam, Issa, Ahmed & Pahi, 2019; Thongrawd, Bootpo, Thipha & Jermsittiparsert, 2019). OCB is defined as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system and that in aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Dennis, 1988; Chavaha, Lekhawichit, Chienwattanasook & Jermsittiparsert, 2021). In the hospitality sector, when employees perform beyond their job roles, they are thought to deliver outstanding services that exceed expectations of customers (Qu & Ma, 2011). But OCB is a wider term, more flexible than that customer-centered emphasis implies. Scholars seem to have two principal approaches with respect to the OCB dimensions and how it should be implemented. The first is Dennis, (1988) who classified OCB into five behavioral types: altruism, courtesy, conscientiousness, civic virtue and sportsmanship. Despite the adaptation of this approach, researchers even now portray OCB as comprising different types of behavior. The three dimensions of organizational citizenship behavior used by Whiting, Podsakoff, Podsakoff & Mishra, (2011) are organizational loyalty, voice behavior and HB. The next approach is to categorize OCB dimensions based on the target of behavior. Zhong, Farh & Organ, (2004) for instance claimed that HB to be reflecting ‘individual’ citizenship behavior; whilst the ‘organizational’ perception of citizenship behavior is voice behavior. Qu & Ma, (2011) more precisely describe OCB as targeting co-workers, clients or stakeholders in particular. A positive and significant CSR-OCB relationship have been revealed by many studies in general as well as in hospitality sector (Omar et al., 2017; Rhou et al., 2017). In both approaches to depicting the OCB dimension, HB is common. Helping behaviour like trying to solve the problems of colleagues, helping them in their work and guiding new employees will contribute to better team performance and more successful operations, and utilizing monetary and human capital (Dennis, 1988). HB is said to be necessary in the hospitality industry, but not much studies have been done to show how CSR practices influence HB. Blunschi & Raub, (2014) in their study found out that there is a significant correlation between CSR awareness and HB of co-workers. After studying the correlation between CSR awareness and OCB, they suggested that in order to enable the active participation of staffs, CSR practices must be tailor-made inside hotels. Nevertheless, no empirical evidence has been found that examined CSR participation or CSR perception impact on HB. Khosa, Ishaq & Kamil, (2020) argue that more physical involvement by employees at work means they are more engaged. The current research will therefore investigate the behavioral measure of CSR participation, along with the cognitive measure of CSR perception, and will outline the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 - Helping behaviour is influenced by corporate social responsibility perception.

Hypothesis 2 – Helping behaviour is influenced by corporate social responsibility participation.

Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility, MW and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Many researchers have proposed an individual’s assessment process or internal mechanisms possibly mediates the relation between CSR perception and work outcome. Organizational commitment, for instance was found to have mediated the link between CSR perception and organizational citizenship behavior (Li et al., 2014). Within the context of organizational psychology studies, the concept of MW is generally acknowledged as different from work alone. According to Dekas, Rosso & Wrzesniewski, (2010), MW is referred to as “work experienced as particularly significant and holding more positive meaning for individuals”. Richard & Oldham, (1976) suggested that the basic features of a job, like autonomy, array of skills, task significance, task identity and feedback, could promote the work experience of employees. Meaningfulness at work may be fostered through those CSR practices that promote the beliefs, values and goals of the organization. MW enables workers to feel more complete and inspired and to feel more connected to their company (Ante, 2012; Khosa et al., 2020). A higher level of citizenship behavior has been seen to be exhibited by those employees with higher levels of perceived MW. Jung and Yoon’s (2016) study revealed that the meaning of work of an employee’s enhances their job participation, which eventually leads to more commitment to the hotel. In the hospitality industry, task significance was found to mediate the relation between CSR awareness and OCB dimensions, like HB (Blunschi & Raub, 2014). They suggested that when an employee is aware of the CSR activities of his hotel, his sense of MW and the belief that he or she is capable of making a difference in the lives of others would increase. This is the only research that supports the notion that more knowledge of the hotel's CSR practices increases meaningfulness and citizenship. However, there is no empirical evidence as to whether MW is predicted by active CSR participation. Hence, to fill this gap, this study postulates the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 - The influences of CSR participation and CSR perception on HB is mediated by MW.

Generation as a Moderator

Young and new workers who enter the work force may have different beliefs from past generations (Chi et al., 2013). The word ‘generation’ denotes a category of individuals who have come into being in their lives at the same time as sharing significant social and historical perspectives (Sutton & Smola, 2002). These differences, as demonstrated by past hospitality studies are mostly associated with work attitudes (Chi et al., 2013), work values (Maier, Gursoy & Chi, 2008), organizational citizenship behavior (Blomme, Lub & Bal, 2011), work engagement (Gursoy & Park, 2012), turnover intention and job satisfaction (Gursoy & Lu, 2016). When work values are considered, Gen X placed more value on work-life balance and job security; whilst Gen Y appreciated jobs that were challenging and had a desire for flexible work environments (Chi et al., 2013). Hence it seems that the work value and preferences are different for every generation which then translates to the meaning they put on work. Bonnema & Hoole, (2015) revealed that the way older Baby Boomers linked meaning to work was different from that of Gen Y. The explanation for this was that the Baby Boomers have had experienced more than the millennial. Compared to the older generation, the younger generation is not motivated to engage in work in the hospitality sector since they find the work less meaningful (Gursoy & Park, 2012). It has been indicated by past researches that Gen Y possess different characteristics, but there is lack of studies that investigates if this difference translates into a CSR-OCB linkage. However, Song et al., (2016) studied the determinants of pro-environmental behaviors of employees, and according to the findings, it was concluded that there was a difference between Gen X and Gen Y in the effects of self-motivation on the behavior of employee’s. Bhattacharya & Sen, (2001) highlighted the value of recognizing how consumer groups are prone to react to particular CSR activities, suggesting that moderating factors are omnipresent. It should also be ensured that an anticipated relationship may not be applicable to every employee. The reasoning here is that a group of people having different beliefs, behaviors and desires can also have different views regarding relationships with the same variables. Attributed to differences in preferences and experience among the both generations, current research attempts to provide suggestions on ways to handle generational differences at work place, specifically in the relationships between CSR, MW and OCB. Hence, for addressing this gap, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 – A significant difference exists in the relationships between corporate social responsibility, MW and HB in Gen X and Gen Y.

Collection of Data

Data was collected from employees of 10 four-star hotels in Krabi, a resort town in Thailand, which is a center of world class tourism. All these hotels are engaged in CSR practices. 350 questionnaires in total were distributed to the 10 hotels and after a span of 2 weeks, out of the 350 surveys, 265 were collected and by discarding 15 questionnaires due to incomplete data, finally 250 (71.43 per cent response rate) were selected for analysis.

Measurement Scales

Self-administered questionnaires were used for measuring 4 variables- employee’s perceptions of the CSR reputation of the hotel, meaningful work, personal CSR participation and organizational citizenship behavior. For measuring CSR perception, six (6) items and for measurement of CSR participation, four (4) items were adapted from Panagopoulos, Vlachos, and Rapp (2014). Meaningful work was assessed using six (6) items that have been adapted from Gilson, May & Harter, (2004). Lastly, for assessment of OCB, five (5) items have been adapted from MacKenzie, Podsakoff, Moorman & Fetter, (1990). Five-point Likert type scale that ranged from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree” was used for all items.

Self-administered survey’s will probably have a biased effect on variable’s measurement (MacKenzie, Podsakoff & Podsakoff, 2012), hence by using survey designs and suitable assessments for Common Method Bias (CMB), these biased effects need to be minimized. The most effective ways of controlling Common Method Variance (CMV) is by using both statistical and procedural remedies (Park, Min & Kim, 2016). Procedural remedy was applied by letting items be simple and clear, assuring participant’s anonymity. In addition, for getting a feedback on the ability of participant to respond accurately, a pilot test and pre-tests have also been conducted along with interviewing the managers of the hotels. Three statistical control have been used in the current research. The first and second test involves assessment of the indicators as a single-factor, whereas in the outer model a method factor is added in the third test. Firstly, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted by inputting the self-reported constructs of employees into a principle component factor analysis. CMB occurs when the value of factor analysis is greater than 50 percent of the co-variation in the variation. According to the result of factor analysis, all factors accounted for below 50 percent of co-variation in the data. Next, the authors performed a confirmatory factor analysis and results showed that one-factor model do not appropriately fit the data (χ2= 579.36, df = 85; p < 0.05; CFI = 0.79; RMSEA = 0.14). On the other hand, a four-factor model appropriately fits into the data (χ2= 269.27, df = 83; p < 0.05; CFI = 0.89; RMSEA = 0.08). Lastly, an unmeasured latent method factor-test was done. Factor loading of every item became less by 0.20 on average when unmeasured method factor was added into the outer model. For measuring CMB’s effect, the squared ratio of the average reduction in factor loading (e.g. .20), the average value of loading without including the ‘unmeasured method factor’ (0.78) is computed. The decrease in factor loading equals averagely to below 8 percent of the variance of all indicators that CMV accounts for. Thus, from the result of all the three statistical tests, it can be said that CMV is not a major issue in the current research.

Analysis of Data

For examination of the model, partial least square-structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was used in three phases. In the first phase, the measurement model is validated that includes testing reliability, discriminant and convergent validity. On the basis of heuristic criterion which is determined by the predictive capability of the model, the structural model is examined in the second phase. In the current research, the result of structural model is assessed as per recommendation of (Hair Jr, Hult, Ringle & Sarstedt, 2017), i.e. - testing of significance of path coefficient, Coefficient of Determination (R2), Predictive Relevance (q2) and f2 and q2 effect sizes. In the last phase, for testing of Hypothesis 4, the complete inner model is evaluated by comparison of the participants in both the generations - Gen X and Gen Y by using multi-group analysis (MGA). Measurement invariance of composite method (MICOM) has been recommended by Sinkovics, Henseler, Ringle & Sarstedt, (2016) for ensuring that the difference in the structural relationship do not arise from distinct meanings of the variables. In MICOM, assessment of configural invariance and compositional invariance assessment is done. The least sample size must be ten times the greatest number of indicator for measuring a variable as indicated by a PLS-SEM sampling guideline (Hair Jr et al., 2017). Hence, for this research, the minimum sample size needs to be 40. As such, for estimation of the path model and multi-group analysis, the sample size of Gen X is 66 and that of Gen Y is 184.

Finding

Demographic Profile

Amongst the 250 participants of the survey, most of employees were females (70 per cent). From Gen Y, there were 184 (73.6 per cent) participants and Gen X consisted of 66 (26.4 per cent) participants. Maximum of the participants (52 per cent) were bachelor’s degree holders. The participants were mostly from the following sections: front office (19 per cent); house-keeping (18.5 per cent); accounts (17.9 per cent) and food and beverages (13 per cent).

Measurement (Outer) Model Evaluation

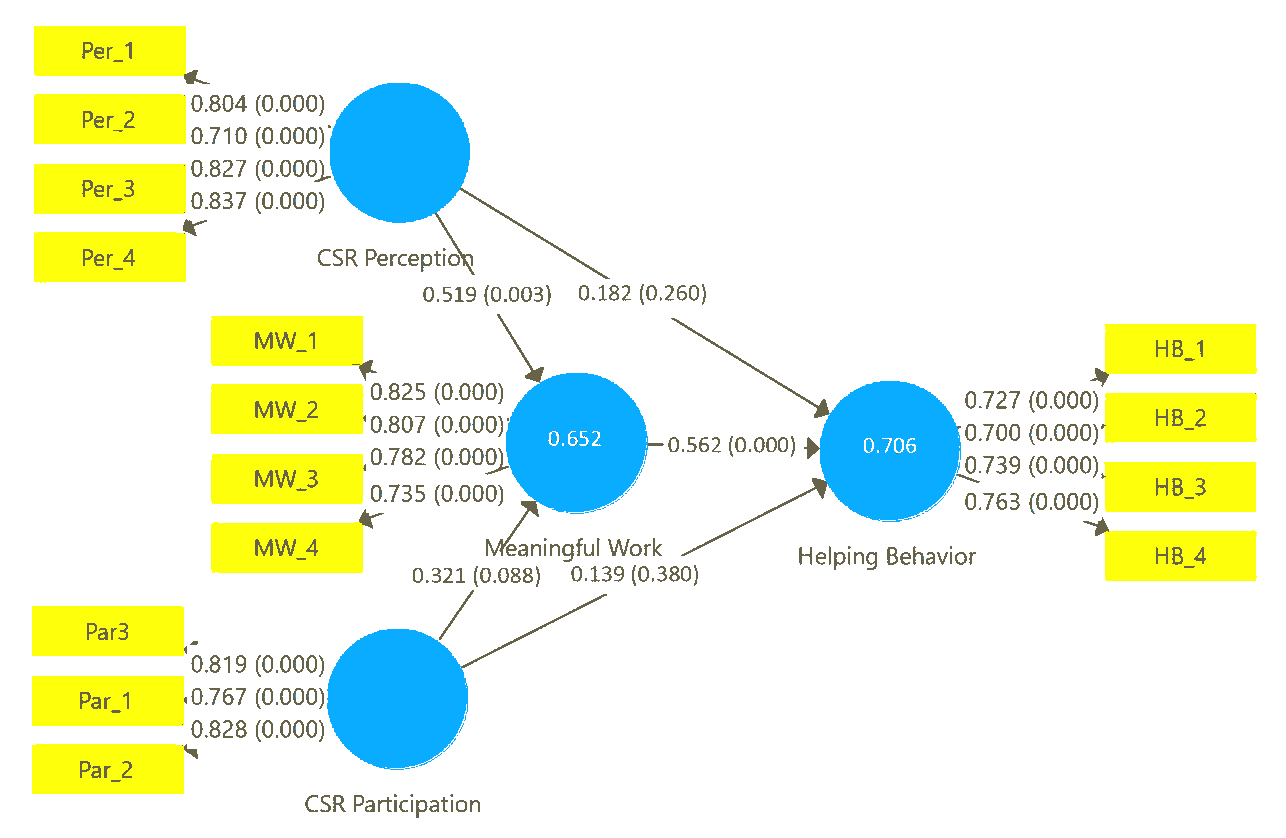

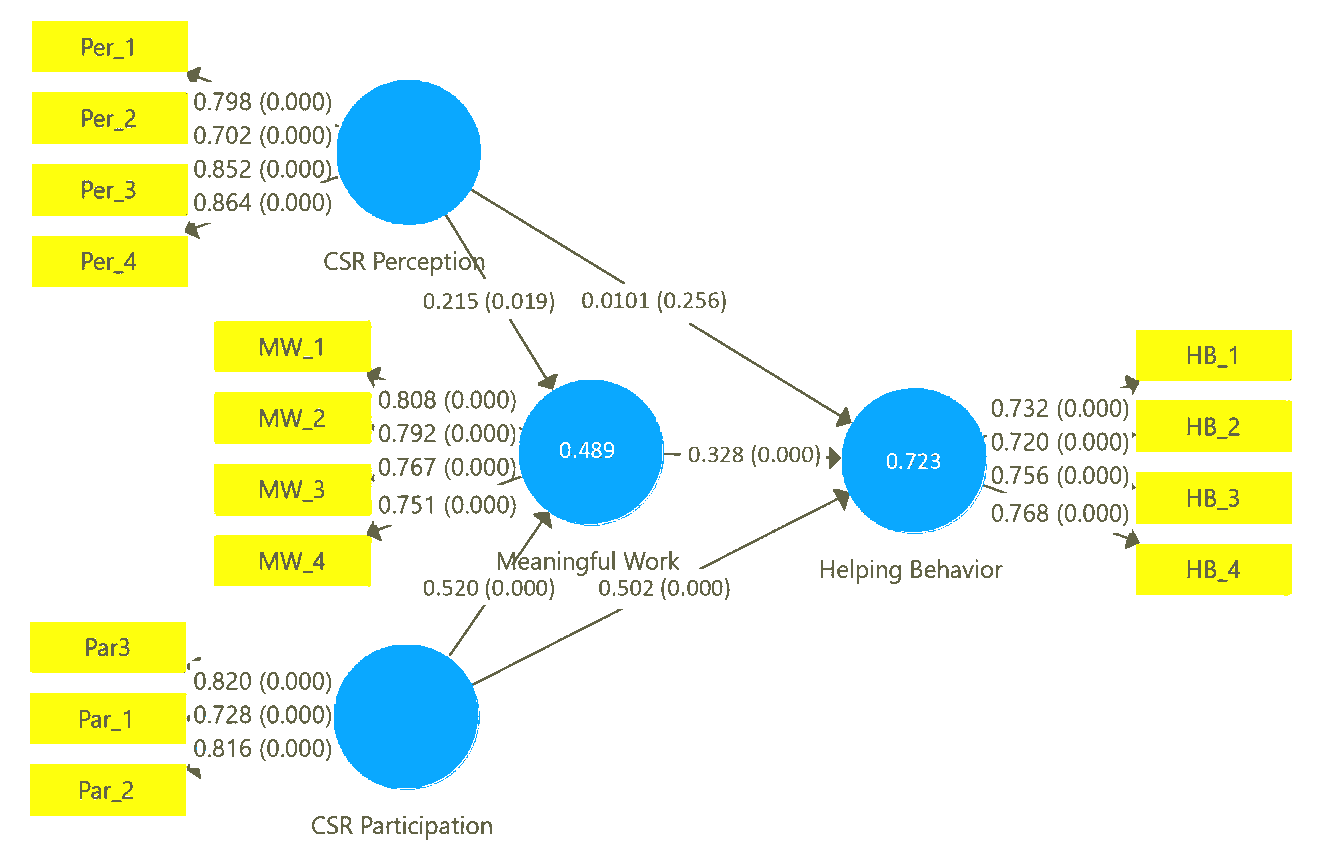

For the evaluation of the outer model, smart PLS with bootstrap method (5,000 subsamples) was employed. The reliability, discriminant validity and convergent validity (CV) of every model have been tested. Item loadings must be greater than 0.7 for being acceptable (Hair Jr et al., 2017). 6 items had loadings below 0.7 and thus they have been eliminated. As shown in Table 1, the remaining items had loadings of more than 0.7, thus confirming composite reliability (CR). The threshold value for CV to occur is 0.50 (Baguzzi & Yi, 1988). The values of average variance extracted (AVE) were greater than 0.5, hence suggesting that CV was satisfactory. In this study, Fornall & Larcker, (1981) criteria have been used for assessing discriminant validity. As shown in Table 2, AVE’s square root values is more than the correlations between the variables, confirming discriminant validity. Furthermore, R2 value suggests that in Gen Y 48.9 per cent of variance in MW and 72.3 per cent of variance in HB can be elucidated by other variables present in the framework. Hence, CV is supported.

| Table 1 Outer Model Result |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constructs | Indicators | Loadings | AVE | CR | ||||||

| All | Gen-X | Gen-Y | All | Gen-X | Gen-Y | All | Gen-X | Gen-Y | ||

| CSR | PER_1 | 0.82 | 0.804 | 0.798 | 0.77 | 0.708 | 0.814 | 0.96 | 0.927 | 0.96 |

| Perceptions | PER_2 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.702 | ||||||

| PER_3 | 0.84 | 0.827 | 0.852 | |||||||

| PER_4 | 0.87 | 0.837 | 0.864 | |||||||

| CSR | PAR_1 | 0.84 | 0.819 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.667 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.889 | 0.915 |

| Participation | PAR_2 | 0.79 | 0.767 | 0.725 | ||||||

| PAR_3 | 0.84 | 0.828 | 0.816 | |||||||

| Meaningful Work | MW_1 | 0.83 | 0.825 | 0.808 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.681 | 0.93 | 0.957 | 0.912 |

| MW_2 | 0.82 | 0.807 | 0.792 | |||||||

| MW_3 | 0.8 | 0.782 | 0.767 | |||||||

| MW_4 | 0.75 | 0.735 | 0.751 | |||||||

| Helping Behaviour | HB_1 | 0.73 | 0.727 | 0.732 | 0.68 | 0.664 | 0.688 | 0.89 | 0.891 | 0.882 |

| HB_2 | 0.73 | 0.7 | 0.72 | |||||||

| HB_3 | 0.75 | 0.739 | 0.756 | |||||||

| HB_4 | 0.78 | 0.763 | 0.768 | |||||||

| Table 2 Fornell-Larcker Criterion |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | All | Gen-X | Gen-Y | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| CSR Perceptions | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.9 | |||||||||

| CSR Participation | 0.714 | 0.89 | 0.772 | 0.81 | 0.742 | 0.92 | ||||||

| Meaningful Work | 0.608 | 0.684 | 0.85 | 0.775 | 0.704 | 0.91 | 0.554 | 0.64 | 0.82 | |||

| Helping Behaviour | 0.677 | 0.77 | 0.754 | 0.82 | 0.691 | 0.648 | 0.774 | 0.81 | 0.675 | 0.81 | 0.715 | 0.8 |

Structural Model

For examination of the hypothesized model, PLS-SEM with 5,000 iterations of subsamples was used. In case of the direct effects, Hypothesis 1 posited that CSR perception influences HB and hypothesis 2 posited that CSR participation influences HB. As shown in Table 3, all the path coefficients, except for CSR perception to HB (beta value = 0.132 and p>0.05) were found to be positive and significant. Thus, hypothesis 1 is not accepted and hypothesis 2 is supported fully. Hypothesis 3 anticipated that CSR participation and perception impact on HB is mediated by MW. Results revealed indirect-only pattern of mediation in CSR perception and HB, which means there will be a full-mediation or indirect-only mediation when there is significant indirect effect of the exogenous construct on the endogenous construct via the mediator and when the direct effect of the exogenous construct on the endogenous construct is not significant (Lynch, Zhao & Chen, 2010). As per the result, 95 per cent “bias corrected bootstrapping Confidence Interval” (CI) does not have value of zero (0) (0.06 to 0.18; p < 0.01), which indicates MW fully mediated corporate social responsibility perception effect when the insignificant direct effect was present. To be more precise, when MW plays the role of a mediator, significant effect of CSR perception on HB occurred. Results also revealed another pattern of mediation – complementary or partial mediation which happened in the relationship between CSR participation and HB. The link between corporate social responsibility participation and HB is significantly mediated by MW (0.11 to 0.27; p < 0.01). Thus, MW partially mediated CSR participation’s effect on HB, which means this study supports hypothesis 3.

| Table 3 Hypotheses Testing Results |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationships | Beta-value | C.I | f2 | Beta Difference | Model Decision | |||||||

| All | Gen-X | Gen-Y | All | Gen-X | Gen-Y | All | Gen-X | Gen-Y | MGA | Full Model | ||

| Perceptions → HB | 0.132 | 0.201 | 0.112 | [−0.04, 0.28] | [−0.18, 0.44] | [−0.08, 0.29] | 0 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.091 | Rejected | Rejected |

| Participation → HB | 0.451** | 0.161 | 0.495** | [0.29, 0.59] | [−0.17, 0.46] | [0.31, 0.66] | 0.2 | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.330* | Supported | Supported |

| Perception → MW | 0.263** | 0.510** | 0.211** | [0.18, 0.48] | [0.23, 0.83] | [0.03, 0.36] | 0.1 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.311* | Supported | Supported |

| Participation → MW | 0.494** | 0.294 | 0.535** | [0.31, 0.62] | [−0.07, 0.61] | [0.34, 0.69] | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.21 | 0.241 | Rejected | Supported |

| MW → HB | 0.350** | 0.551** | 0.360** | [0.25, 0.47] | [0.28, 0.87] | [0.27, 0.43] | 0.2 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.19 | Rejected | Supported |

| Perceptions → MW → HB | 0.137** | 0.276** | 0.091 | [0.06, 0.18] | [0.06, 0.65] | [0.03, 0.15] | - | - | - | 0.181* | Supported | Supported |

| Participation → MW → HB | 0.194** | 0.15 | 0.187** | [0.11, 0.27] | [−0.07, 0.39] | [0.11, 0.30] | - | - | - | 0.037 | Rejected | Supported |

Furthermore, the results of R2 showed that the other variables explain 70.6 per cent variance of HB. The extent to which the independent variables contribute to the R2 values of the latent constructs is indicated by effect size f2. As shown in Table 3, MW (f2= 0.21) and CSR participation (f2= 0.19), have moderate effects on HB while CSR perception’s effect (f2=0.03) has small impact. When MW is the dependent variable, CSR participation has moderate effect size (f2=0.17), whereas CSR perception’s effect was small (f2=0.07). The blindfolding method that estimate q2 values, explain the extent to which the originally observed values can be predicted by the path model. Effect size q2 in the MW-HB relationship is small (q2 = 0.05), which means that the predictive relevance of MW for HB is small. (Figure 1, 2)

Multi-Group Analysis

MICOM was performed before the final step of the analysis for ensuring that same items were used for the outer models and for obtaining acceptable reliability for all the variables. The assessment result of outer models of both generations are displayed in Table 1. In the first step, configural invariance’s assessment have been established. Results of assessment of measurement invariance is displayed in Table 4. In the second step compositional invariances’ assessment has been done. The third step was the assessment of equality of composite mean value and variance in the groups. The confidence intervals of the differences in mean value and variances included zero (0) indicating that equal composite mean value and variance. After the three steps have been established, full measurement invariance of both the dataset have been supported.

| Table 4 Using Permutation Outcomes of Invariance Measurement Test |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Decision (Full Invariance Measurement) | |||||

| Configural | Correlation = 1 | Confidence | Compositional | Equal | Equal Mean | ||||

| Invariances | Interval | Invariances | Variance | value | |||||

| Difference | C.I | Difference | C.I | ||||||

| CSR (Participation) | Supported | 0.998 | [0.996, 1.000] | Supported | -0.02 | [−0.48, 0.38] | -0.002 | [−0.30, 0.31] | Supported |

| CSR (Perceptions) | Supported | 1 | [0.998, 1.000] | Supported | -0.02 | [−0.54, 0.40] | -0.003 | [−0.30, 0.31] | Supported |

| MW | Supported | 0.999 | [0.997, 1.000 | Supported | -0.02 | [−0.49, 0.47] | -0.002 | [−0.32, 0.32] | Supported |

| HB | Supported | 0.996 | [0.993, 1.000] | Supported | -0.02 | [−0.45, 0.39] | -0.001 | [−0.33, 0.30] | Supported |

By using the data of Gen X and Gen Y, multi-group analysis was conducted after MICOM. According to Hypothesis 4, there would be a significant difference in the relationships between CSR, MW and HB in both the generations. Comparison of both models was done by testing both models’ significant difference. Similar variance has been explained by the explanatory power in Gen X HB (R-square = 0.706) and Gen Y (R-square = 0.723). When we compare all models’ datasets, results revealed significant difference between the path coefficients of: I) CSR perception’s influence on MW (βeta difference = 0.311); II) CSR participation’s influence on HB (βeta difference = 0.241) and III) CSR perceptions’ influence on HB via MW (βeta difference = 0.181). The result of path coefficients is shown in Table 3. In Gen X, MW was found to be strongly influenced by CSR perception (beta value = 0.51) but the effect was weak in Gen Y (beta value = 0.21). Even MW’s mediating effect in the relation among corporate social responsibility perception and HB is more in Gen X (beta value = 0.276) than in Gen Y (beta value = 0.091) Hence, CSR perception’s effect on HB was mostly seen in Gen X. However, CSR participation’s effect on HB was stronger in Gen Y (beta value = 0.495) than in Gen X (beta value = 0.161), thus supporting hypothesis 4.

Discussion and Implication

The current research has contributed in a few significant ways to literature. A mediation model has been developed and tested that incorporates and expands past work that is related to effects of CSR activities. The findings of the current research are similar to previous study that claimed positive relation between CSR activities and employee behavior (Panagopoulos et al., 2014). Thus, desirable employee behavioral outcomes are influenced by corporate social responsibility, through a mediator such as MW. This study also tests difference in generations to moderate these relationships. The current research also shows that the CSR-OCB relationship is much more complicated than was modelled by earlier studies. The findings of the current research support findings of past work by Omar et al., (2017) who have revealed a relationship to be existing in between corporate social responsibility and organizational citizenship behavior. Similarly, the hospitality industry researchers have established a significant and positive CSR-OCB association (Li et al., 2014; Luu, 2017; Rhou et al., 2017). OCB is not predicted by CSR perception, as opposed to earlier study results. In addition, a robust explanatory model to predict HB was found when the influential effects of the two CSR constructs were compared. Hence, only CSR perception might not be enough for explaining fully its effects on OCB and any mediator. Even though results did not support the direct effect of CSR perception to HB, it was shown that MW fully mediated the relationship between the two. To put in another way, HB is not directly influenced by CSR perception, but indirectly via MW. However, similar to past study (Blunschi & Raub, 2014), CSR participation influenced OCB when MW played the role of a mediator. This is the first study that examines CSR participation actions to predict employee’s work outcome.

How OCB is represented as a HB is another contribution to the literature. Blunschi and Raub (2014) modelled HB of coworkers as OCB’s stand-alone dimension and said that there was a significant relationship between CSR awareness and HB of coworkers. The findings of the current research extend this work and demonstrates how CSR participation and CSR perception specifically influences HB.

Contributing to the literature, this study also put forward the mediating role of MW between particular CSR constructs and HB of coworkers. While the study findings are similar to previous research indicating the mediating function of MW, the current literature is expanded further. Further, MW’s role have been studied in the hospitality industry, only one study in this sector has been conducted to investigate its mediating role in between CSR construct and OCB. Blunschi and Raub (2014) found that task significance mediated the link between CSR awareness and OCB dimension, which includes HB. This study thus confirms that when an employee is aware of the CSR practices of the hotel, it increases his sense of MW and contribute to citizenship behaviour.

Findings of this study offer few implications for hospitality managers. Since CSR participation was found to effectively promote beneficial work outcome, it is suggested that companies must develop strategies and practices so that there is more CSR participation within employees. Management can thus invest on resources related to CSR activities with more confidence. Hotels should find the types of CSR programs that workers would like most to participate in for supporting the recipients of corporate social responsibility and hotels acts.

The present research also adds to the body of knowledge as it focuses on the CSR-OCB relationship, especially on Gen Y, and it was found that there is a difference in how this relationship varies across different generations. CSR participation promotes HB more in Gen Y than Gen X. The reason for this could possibly be that Gen Y prefers teamwork and working collectively for accomplishing a task (Maier et al., 2008). In Generation X, MW fully mediated the relation between CSR perception and HB, indicating its importance on promoting HB amongst employees in the hospitality sector. Thus, for Gen X employees, more attention must be paid on MW by managers for desired work behaviors. Hence, it would be beneficial if different CSR practices are customized for different generations.

Additionally, collegial relationship amongst coworkers are formed as a result of CSR participation which enhances the organisational culture of the hotel (Butcher, Supanti, & Fredline, 2015). Possessing such features such as caring, helping, empathy has a positive impact on their services. It is recommended that hospitality managers should hire people having both hard and soft-side abilities, like professionalism, to match the internal and external facets of a hospitality career better. Managers of hotels therefore must design jobs to suit their workers (Tang, Bavik & Bavik, 2017) and have improved exposure to CSR participation. Also, apart from the top management, even the younger employees need to be involved in decision-making for the CSR practices. Participation must thus take place in every phase of the process rather than only when it is being implemented. It should also be understood that CSR participation does necessarily not enamor all employees, hence employee interests and needs must be considered while planning CSR participation.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Cross sectional method was used for collecting data from a single source by use of self-administered questionnaires, hence rising concerns of generalizability of the findings. In future research, multiple sources must be considered while the model is tested and validated, since there was lack of CMB. Similarly, by using self-administered questionnaires, social desirability biases can be raised, in particular with self-performance issues. While all the hotels selected for the survey were active in CSR operations, they did not generally implement CSR in the same domains at the same extent. Although this dimension offers a level of generalizability, implementing this framework in various services sector domains, such as including various corporate social responsibility settings will be beneficial. This will provide greater comprehension of how, through MW, the impact of various types of CSR activities contributes to better organizational citizenship behavior, such as HB. It is also suggested to conduct studies on hotels in other regions and across different cultures. Also, the size of hotel and type of ownership may be used as a moderator in further studies. Comparison of demographic factors may also be done, such as tests of younger and older Gen Y participants. HB was a major element in this study, but upcoming researchers can use other OCB aspects, specific to hospitality and generations of the employees in this industry.

References

- Ante, G. (2012). Employee engagement and sustainability: a model for implementing meaningfulness at and in work. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 13(46), 13-29.

- Ashforth, B.E., & Mael, F. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103-123.

- Baguzzi, R.P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94.

- Bhattacharya, C.B., & Sen, S. (2001). Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 225-243.

- Bhattacherya, C.B., Korschun, D., & Sen, S. (2008). Using corporate social responsibility to win the war for talent. MIT Sloan Management Review, 49(2), 37-44.

- Birtch, T.A., Chiang, F.F., & Van Esch, E. (2016). A social exchange theory framework for understanding the job characteristics–job outcomes relationship: The mediating role of psychological contract fulfillment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(11), 1217-1236.

- Blomme, R.J., Lub, X.D., & Bal, P.M. (2011). Psychological contract and organizational citizenship behavior: A new deal for new generations. Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, 7(1), 109-130.

- Blunschi, S., & Raub, S. (2014). The power of meaningful work: How awareness of CSR initiatives fosters task significance and positive work outcomes in service employees. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 55(1), 10-18.

- Bonnema, J., & Hoole, C. (2015). Work engagement and meaningful work across generational cohorts. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 1-11.

- Butcher, K., Supanti, D., & Fredline, L. (2015). Enhancing the employer-employee relationship through corporate social responsibility (CSR) engagement. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(7), 1479–1498.

- Chavaha, C., Lekhawichit, N., Chienwattanasook, K., & Jermsittiparsert, K. (2021). the impact of servant leadership on the organizational citizenship behavior: Mediating Role of Psychological Ownership. Psychology and Education, 58(2), 3083-3097.

- Chi, C.G.Q., Gursoy, D., & Karadag, E. (2013). Generational differences in work values and attitudes among frontline and service contact employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 32(1), 40-48.

- Dekas, K.H., Rosso, B.D., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30(1), 91-127.

- Dennis, O. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington MA: Lexington Books/DC Heath and Com.

- El Akremi, A., Gond, J.P., Swaen, V., & Babu, N. (2017). The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person‐centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 225-246.

- Farrukh, M., Sajid, M., Lee, J.W.C., & Shahzad, I.A. (2020). The perception of corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Examining the underlying mechanism. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(2), 760-768.

- Fornall, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Frenkel, S.J., & Bednall, T. (2016). How training and promotion opportunities, career expectations, and two dimensions of organizational justice explain discretionary work effort. Human Performance, 29(1), 16-32.

- Gangi, F., Mustilli, M., & Varrone, N. (2019). The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) knowledge on corporate financial performance: evidence from the European banking industry. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(1), 110-134.

- Gilson, R.L., May, D.R., & Harter, L.M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11-37.

- Glavas, A., & Aguinis, H. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932-968.

- Greenwood, M., & Voegtlin, C. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Human Resource Management Review, 26(3), 181-197.

- Gursoy, D., & Lu, A. C.C. (2016). Impact of job burnout on satisfaction and turnover intention: do generational differences matter? Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(2), 210-235.

- Gursoy, D., & Park, J. (2012). Generation effects on work engagement among US hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(4), 1195-1202.

- Hair Jr, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): Sage publications.

- Hosseini, E., Tajpour, M., Lashkarbooluki, M. (2020). The impact of entrepreneurial skills on manager's job performance. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management, 5(4), 361-372.

- Jermsittiparsert, K., Siam, M., Issa, M., Ahmed, U., & Pahi, M. (2019). Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible?: The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 7(4), 741-752.

- Johns, G., Donia, M.B., Raja, U., & Ayed, K.B.A. (2018). Getting credit for OCBs: Potential costs of being a good actor vs. a good soldier. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(2), 188-203.

- Khosa, M., Ishaq, S., & Kamil, B.A.M. (2020). Antecedents of employee engagement with the mediation of occupational stress and moderation of co-worker’s support in the banking sector of Pakistan. International Journal of Management Studies and Social Science Research, 2(1), 45-62.

- Korn Ferry Institute. (2015). Attracting and Retaining Millennials in the Competitive Hospitality Sector. Retrieved from https://www.kornferry.com/institute/attractingand-retaining-millennials-in-the-competitive-hospitality-sector

- Li, Y., Fu, H., & Duan, Y. (2014). Does employee-perceived reputation contribute to citizenship behavior? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26(4), 593–609.

- Luu, T.T. (2017). CSR and organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(11), 2867–2900.

- Lynch, J.G., Zhao, X., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197-206.

- MacKenzie, S.B., Podsakoff, P.M., Moorman, R.H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers' trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107-142.

- MacKenzie, S.B., Podsakoff, P.M., & Podsakoff, N.P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539-569.

- Maier, T.A., Gursoy, D., & Chi, C.G. (2008). Generational differences: An examination of work values and generational gaps in the hospitality workforce. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 27(3), 448-458.

- Nikraftar, T., & Hosseini, E. (2016). Factors affecting entrepreneurial opportunities recognition in tourism small and medium sized enterprises. Tourism Review, 71(1), 6-17.

- Omar, F., Rupp, D.E., & Farooq, M. (2017). The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Academy of management journal, 60(3), 954-985.

- Panagopoulos, N.G., Vlachos, P.A., & Rapp, A.A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi‐study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 990-1017.

- Park, J., Min, H., & Kim, H.J. (2016). Common method bias in hospitality research: A critical review of literature and an empirical study. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 56(1), 126-135.

- Qu, H., & Ma, E. (2011). Social exchanges as motivators of hotel employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: The proposition and application of a new three-dimensional framework. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(3), 680-688.

- Rhou, Y., Kim, H.L., Uysal, M., & Kwon, N. (2017). An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 61(1), 26-34.

- Richard, H.J., & Oldham, G. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250-279.

- Sinkovics, R.R., Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–431.

- Song, H.J., Kim, J.S., & Lee, C.K. (2016). Effects of corporate social responsibility and internal marketing on organizational commitment and turnover intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 55(1), 25-32.

- Sutton, C.D., & Wey Smola, K. (2002). Generational differences: Revisiting generational work values for the new millennium. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 23(4), 363-382.

- Tajpour, M., Hosseini, E., & Moghaddm, A. (2018). The effect of managers strategic thinking on opportunity exploitation. Scholedge International Journal of Multidisciplinary & Applied Studies, 5(2), 68-81.

- Tang, P.M., Bavik, A., & Bavik, Y.L. (2017). Servant leadership, employee job crafting, and citizenship behaviors: A cross-level investigation. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58(4), 364-373.

- Thongrawd, C., Bootpo, W., Thipha, S., & Jermsittiparsert, K. (2019). Exploring the nexus of green information technology capital, environmental corporate social responsibility, environmental performance and the business competitiveness of Thai sports industry firms. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 14(5 Proc), S2127-S2141.

- Whiting, S.W., Podsakoff, N.P., Podsakoff, P.M., & Mishra, P. (2011). Effects of organizational citizenship behaviors on selection decisions in employment interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 310-326.

- WTTC. (2015). Global Talent Trends and Issues for the Travel & Tourism Sector. Retrieved from https://wttc.org/Research/Insights/policy-research/human-capital/global-talent-trends

- Zhong, C.B., Farh, J.L., & Organ, D.W. (2004). Organizational citizenship behavior in the People's Republic of China. Organization Science, 15(2), 241-253.