Research Article: 2022 Vol: 25 Issue: 4S

Military cemeteries as anthropogenic shapes of the physical earth's surface

Marian Rybansky, University of Defence in Brno, Kounicova

Juliana Krokusova, University of Prešov

Citation Information: Rybansky, M., & Krokusova, J. (2022). Military cemeteries as anthropogenic shapes of the physical earth's surface. Journal of Management Information and Decision Sciences, 25(S4), 1-16.

Keywords

Military Cemetery, Anthropogenic Landform, Physical Landscape, Location

Abstract

This paper documents the factors and specifics of the location of the military cemeteries in the physical earth's surface. Military cemeteries represent a specific category of cemeteries. Their creation is linked to dramatic historical warfare. Our research shows that they are a source of historical and geographical information, which does not affect their primary functions, namely funeral, pious and spiritual. Military cemeteries must also be seen as an integral element of cultural and physical landscape, as part of its identity and a site of memory. The location of the military cemeteries is dependent on specific physical-geographical preconditions of the site. So far, military cemeteries have not been considered as military landforms. However, we argue that they are part of military area, have their own characteristics and typical features and fulfil the criteria to be defined as anthropogenic landform. From a spatial point of view, in our research we focused on the area of â??â??north-east Slovakia where the majority fighting took place on the Eastern Front during the First and Second World Wars. The historic military region of the Dukla battlefield is also part of the study area. This area is particularly interesting from a physical-geographical point of view because it is located in the Carpathians. The rough mountain relief and dense forests determined not only the progress of the army and the course of military operations but also the location and character of the military cemeteries in the studied area.

Introduction

The current geopolitical situation in the world is characterized by increased military conflicts. Mankind has not learned from the drastic consequences of World Wars. War cemeteries are like black spots on a map where material and spiritual consequences of war overlap.

Cemeteries reflect many aspects of both geography and culture. Demographics, cultural norms, social relationships and histories of families are just a sampling of the wealth of information found in cemeteries. This paper focuses on the study of military cemeteries as a tool for studying how the spatial and temporal aspects of cultural phenomena can be used for geographical and anthropological study. Military cemeteries reflect geopolitics, war ambitions, migrations of soldiers and demographics.

Military cemeteries stand at the intersection of exploration of several geographical fields of study. They are part of a cultural landscape, national and local heritage, their presence in a particular region and a site is part of the identity and site of memory. Nowadays, it is important to remind military cemeteries, memorials and monuments as the part of our heritage (Light, 2016). Their localization, structure, design, architecture and emotions that emit are a harmonic and integral part of the site itself. Each military cemetery is part of a particular geographical area; its location is determined by physical-geographical conditions of the site. At the same time, military cemeteries meet the criteria of being defined as anthropogenic landforms in terms of modern anthropogenic geomorphology (?ech & Krokusova, 2013). Military cemeteries are an integral part of military history and military area. Military cemeteries have mainly been the object of interest of politics (in terms of post-war peace treaties, conventions and treaties relating to the maintenance and care of these graves). They are part of military and regional history; according to Fuchs (2004) cemeteries became more than sites of mourning; they became historical documents that recorded some of realities of war. As reported in Fogli (2004 cited Uslu, Baris & Erdogan, 2009) cemeteries have religious, symbolic, philosophical and artistic meanings for disciplines like theology, history of art and anthropology and they are gaining importance as “ecological reserve areas” or potential green areas for branches of science dealing with urban planning or ecology. Cemeteries have given families of fallen soldiers places to mourn and remember (Ebel, 2012). European military cemeteries of World War I and World War II are relatively well mapped. The biggest and most important of them are located near major battles and fronts, strategic points and the lines of defense. Up to these days, there have preserved many sketches, maps of their plans, lists of soldiers in graves and other archival materials documenting historical events that led to their creation. However, many cemeteries are ruined and it is difficult to identify graves in the field. Any state, which took part in a war, has its cemeteries with own fallen soldiers, but there are also graves and cemeteries with fallen enemies. Common cemeteries of former war allies and adversaries are the expression of overcome of political and ideological divides (Popa, 2013). Military cemeteries were and still are sensitive issue of war conflicts.

The issue of cemeteries was often taboo in the past; however, we can observe a gradual acceptance of the cemetery as an object of scientific research in last decades. A shift in their perception points out Rugg (2000), since cemetery space can be regarded as sacred; it is protected from activities deemed 'disrespectful'. However, cemeteries are principally secular spaces. As a pioneering study we may consider The Secret Cemetery (Francis, Kellaher, Neophytou, 2005) on cemetery landscapes, religious and cemetery forms and structure of cemeteries. Scientific papers on cemeteries study especially local specifics of cemeteries (Francaviglia, 1971; Riedesel, 1980; Hannon, 1989; Cox, Giordano & Juge, 2010; Rallis, 2011; Gudný, 2012). Special attention is paid to national or unique cemeteries (Atkinson, 2007). The design of military cemeteries and their spatial dimension partly studies Fuchs (2004). In this paper, we focus on this issue and provide a comprehensive view of military cemeteries from the point of view of the location in cultural landscape, structure, design and typology and as a source of geographical information and a site of memory.

Data and Methods

The preparatory phase was primarily focused on the study of published and unpublished literature. At first, we used contemporary historical sources, archival materials (maps, historical sketches of cemeteries and reports of exhumation from the period of additional investigation of post-war cemeteries). The second phase consisted of a review of the international literature, different approaches to the perception and acceptance of cemeteries as part of physical and cultural landscapes.

Many socio-cultural studies consider cemeteries as a locus of memory, site of memory and as an integral part of the local and national heritage. To a lesser extent, the scholarly literature is oriented toward military cemeteries. These works usually have historical and geographical character; case studies are focused on a particular war event and region. The literature lacks a significant theoretical concept or framework defining and accepting military cemeteries as a country element marked by military activities. There are also absent possible approaches to their classification and typology.

The conducted field research formed an essential part of our research work. From the spatial point of view, we focused on the area of north-east Slovakia, which was intensively affected by World War I and World War II. At present, it is possible to identify military anthropogenic shapes in the landscape. Military cemeteries form a special category. During the field research, we focused on common features and specifics of military cemeteries from World War I and World War II. We focused on physical determinations of localization, way of burying, tombstone design and current condition and maintenance. We also used the database of military graves and cemeteries in Slovakia (The Institute of Military History) as a data source and materials of the Club of Military History Beskydy.

In the final stage, we summarized the theoretical materials and the practical knowledge acquired in comprehensive field research. The main outcome of this paper is the study, which allows a comprehensive evaluation of military cemeteries, in terms of physical and geographical as well as cultural and geographical perceptions. A graphical appendix facilitates visualization of the sources gathered.

Theoretical Approaches for Defining Cemetery

Main functions of cemeteries are: place of deposit and transformation of the dead bodies without dangers for the public health and place of visit for those people wanting to remember a dead person and at the same time a symbol of the historical memory of a collectivity (Fogli 2004 cited Uslu, Baris & Erdogan, 2009). For Christians, Jews and Muslims, it is typical to bury into graves located in specially allocated places, called cemeteries (Matlovi?, 2001). Cemeteries are deliberately created and highly organized cultural landscapes (Francaviglia, 1971). In many cultural studies of cemetery, there is significant aspect of understanding the cemetery as a tool for the formation of the socio-cultural identity of living people (Sautkin, 2016). A cemetery represents an anthropogenic form, i.e., an artificial man-made form for the purpose of burying the dead. From the territorial point of, it is an area, which has surface and underground parts that relate to the surface (?ech & Krokusova, 2013). In terms of a genetic-morphological classification of anthropogenic forms, cemeteries belong to burial anthropogenic forms of a landscape (Zapletal, 1969). Military cemeteries are unique and have an interdisciplinary character in terms of a morphological-genetic classification; therefore, they belong to funeral (funebrial), but also military forms of landscape.

Military cemetery represents an anthropogenic form, which has primarily a funeral function (the burial of fallen soldier). At military cemeteries, there are buried soldiers, military officers, commanders, as well as prominent figures of political and social life. Military cemeteries are characterized by their simplicity, uniformity of gravestones and sophisticated spatial structure, and these are qualities that differ them from civil cemeteries, which do not have the same purpose. There are also memorials of important people, generals and heroes, as well as memorials of the fallen who died during significant military attacks and events.

Necrogeography, as a part of geography, focuses on the spatial organization of the cemetery as well as the individual architectural headstones or markers. The first necrogeographic study was Pattison’s (1955) study on Chicago cemeteries. Pattison analysed 227 cemeteries in south-eastern Illinois. His research resulted in a four-type classification system based on the age and size of the cemetery (Pritsolas & Acheson, 2017). In terms of Necrogeography, cemeteries are source of geographical, biographical, historical information and the object of geographical research. They play an important role in art and culture and also provide demographic data on the history of the place and its inhabitants. Cemeteries record information about war events, epidemics and reflect the history of towns and villages. They are a significant part of the cultural heritage. The cemetery connects the physical, cultural and historical legacy which is represented by gravestones, symbols and spiritual signs. This creates a specific atmosphere reflecting the culture of local people. The perception of death, the manner of burying, rituals and traditions associated with the burial, visual configuration and legislative and economic contexts of burying belong to phenomena that vary in space and time. The character of cemetery is affected by physical-geographical conditions (relief, hydrological conditions, flora and fauna) and local socio-historical conditions (history and culture). If the cemetery has some specific purpose, it is due to the fact that there is an overlap between material objects and the spiritual message. The material culture of cemeteries is formed particularly through their architecture. Graves and cemeteries are often the only source of knowledge of distant past and people's lives. A grave itself is a reflection of a funeral ritual. Cemeteries are also considerable elements in land use planning - protection zones, predictions of development and new suitable sites (Hupkova, 2008-2009).

Cemeteries can provide information on the demographic development of the country. There are cemeteries that have problems with a lack of space, other yawn with emptiness. Tombstones can indicate that no new residents move into the municipalities, since most of the dead are buried in old family graves. The location of graves in cemeteries provides information on the religious character of the area. In areas of strong religiosity, graves are oriented particularly in the east-west direction, which corresponds to Christian teachings. Graves in other areas are oriented in different directions. Cemeteries in traditionally religious areas are characterized by a high proportion of family graves, the neatness of graves and high number of grave religious symbols. High number of religious symbols is typical for new graves (Hupkova, 2010).

Military cemeteries are also valuable source of information. Factual data tell us basic information about a soldier's name, date of birth and death, military rank, membership to a particular army, division, and regiment. Further, there is mentioned what war or military operation he fought in and what kind of significant awards received. Appearance and tombstone elements tell us what was his religion, nationality. An overall appearance, size, spatial organization (segregation of soldiers and officers) and a maintained condition of cemetery tell us under what circumstances it arose. The presence of mass graves and frequency of Unknown Soldier’s graves indicate a course and intensity of military operations and more difficult conditions for the burial of fallen soldiers.

Terminology

In connection with the management and maintenance of military cemeteries, there have been published several documents by the General Inspectorate of War Graves. They defined a war grave, military grave and maintenance of war graves and they also characterized a grave properly constituted and grave properly maintained. These documents are located in the Military History Archive in Bratislava. According to the Regulation n. 382008 published by the General Inspectorate of War Graves, it is necessary to limit the time in which the graves of fallen and dead soldiers are termed as war graves. Any other military grave established after that time is a military grave and it is therefore voidable after the expiration of the legitimate time.

War grave is a grave that was established at the time of World War. Exceptions are those cases, where the soldier's death was the result of circumstances that did not have any connection with a state of war emergency and are classified as military (peaceful) voidable graves.

Military grave is any military grave that was established beyond war times and is voidable after the time prescribed by law. This category of graves also includes graves from the times of war, when the death of soldier was caused by circumstance having no connection with the state of war emergency. The state is no longer obliged to take care of military (peaceful) graves after a period of ten years; these graves are voidable if remainders will not assume responsibility for them (Bystricky, 2007).

Understanding the Military Cemetery Landscape

“The proof of the size of a nation is whether it can take care of graves of the dead. Winners and beaten...”

According by Pritsolas and Acheson (2017, p. 51) the cemetery is a tangible, visible result of cultural and spiritual values and economic constraints. For cemetery landscape are important three factors: economic, cultural and physical environment. Military cemeteries represent a specific category within cemeteries; they have specific features that distinguish them from civil cemeteries. Their specificity is based on a number of aspects that overlapped during the process of their creation. Military cemeteries were created as a result of specific historical event (war); they are placed in a particular natural environment (use natural potential of local landscape - wood, stone). They reflect national specificities of fallen soldiers from different parts of the world together with local cultural particularities.

Appearance and Atmosphere of the Place

Appearance of civil and military cemeteries is different at first glance. A civil cemetery is characterized by the diversity of each grave; it expresses the uniqueness and unrepeatable personality of each person. A typical feature of military cemeteries is the unity of tombstones, which significantly differs them from the diversity and richness of civil cemeteries. Due to this feature, war cemeteries have impression of simplicity, orderliness and integrity. Here we can see some parallels, as soldiers stand in rows in the same uniforms during their lives and lie in organized graves with a single design of tombstones after their death. It is an expression of man identification with a certain group of people with the same life mission. Soldiers dressed in uniforms belonging to some army express their identity and fellowship and have an effect of systematic impression as a whole. All this is reflected in the appearance and organization of war cemeteries. Pritsolas & Acheson (2017) argued that for understanding the cemetery landscape are significant both the uniformity and variability. We point to the uniformity phenomenon that is so remarkable for military cemeteries.

Characterizing military cemeteries, we can also speak about the atmosphere of place, which can be differentiated in contrast with civil cemeteries. This depends on various factors. The organization and appearance of graves reflects national specificities of buried soldiers; it particularly includes major participants of war. For instance, German, Russian and American war cemeteries have completely different atmosphere. War cemeteries are very sensitive matter of conflicts, since allies as well as enemies are buried on the state territory, sometimes even side by side in the same cemetery.

Localization

Formation and localization of military cemeteries determined completely different circumstances than in case of civil cemeteries. The presence of military cemeteries binds to space that is linked with military activity or acts of war. During World War I and II, military cemeteries were formed directly at the space related to war (e.g. cemetery at Verdun, Gettysburg, Salisbury or military cemeteries in Dukla Pass in the Carpathians). Nowadays, war conflicts take place in other geopolitical and spatial contexts and burials of fallen soldiers no longer bind to the battlefield (e.g. American soldiers who died during military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan are buried in the United States).

Localization of military cemeteries in landscape has its own specifics; based on terrain research, authors recommend the following classification:

• Areas of great historical battles,

• At the crossing points of military fronts,

• Places of heavy fighting and strategic points (ground elevations, passes)

• Near military bases,

• Near military hospitals, general hospitals and prison camps,

• As segregated part of civil town cemeteries,

• As a separate military cemetery within a town,

• As a part of large cemeteries with national status,

• As a segregated part of rural cemeteries,

• Scattered at the edges of towns or in forests.

Uniformity of Graves

Uniformity of war graves is their main visual manifestation. It is expressed in many ways, one of which is material used for building of gravestones; natural materials are dominant, as military cemeteries were formed under very difficult conditions. Despite dramatic circumstances of their formation, we can observe their harmonic and compositional placement in the surrounding countryside. Most commonly used material for war graves: wood, natural stone, concrete and cast iron.

On the basis of terrain research and studying of scientific literature, authors identified following shapes and motifs, which were used in visual realization of gravestones:

• Cross (wooden cross, stone cross, cast iron cross, cross with or without data of a buried person) Cross most commonly occurs not only in military but also in civil cemeteries. Its symbolism has a strong religious significance; therefore, crosses are found mainly where Christianity is dominant.

• Tabular cross (with data of a buried person) We mainly meet with tabular crosses in German military cemeteries not only in Germany but also in other countries where fallen German soldiers of World War II are buried.

• Board (with data of a buried person) Boards can be of different form; usually have a shape of rectangle, square, diamond, etc. Specific and immediately identifiable boards are typical for Muslim and Jewish soldiers. Tombstones of Soviet soldiers are also interesting, as they demonstrate the grandeur of Soviet Army in the spirit of established ideology (Stangl 2003); gravestones are also covered with images of soldiers in the form of engravings or sculptures.

• Various shapes with dominant military motif For the functioning of army, it is typical strict organization and hierarchy, exactness and precision of instructions, gestures and symbols. Military symbolism is very sophisticated and meticulous. For example, Soviet military cemeteries are not characterized by a dominant symbol of cross, since preferred form is a red star.

Structure of tombstones organization has clear and sophisticated form in military cemeteries:

• Line (regular) structure

• Triangular structure

• Ring structure

• Combined line (regular) structure.

In terms of localization and orientation of gravestones in space we can distinguish:

Vertical localization of tombstones and crosses (upright tombstones) is more common, since it grabs attention. Size, form and used symbolism are means of certain expressions that mediate basic information about buried soldiers.

Horizontal localization of tombstones (flat tombstones) is less frequent. Appearance of military cemetery is very simple and offers harmonious impressions. On the other hand, orientation is demanding in this cemetery, visualization and military symbolism is less apparent.

Personal Authenticity

Despite the integrity, compactness and uniformity, military cemeteries maintain their personal specificity, when the individual personality of a buried soldier is preserved. Although tombstones and crosses are uniform, they express individual peculiarities. Due to their form, symbols and specific signs, we can specify:

• Nationality

During the war, it often happens that members of one army or regiment are soldiers of different nationalities, who are then buried in the same cemetery, often side by side (a flag of the particular state can be an identification symbol at the tomb).

• Religiosity

Religiosity is most common element which is highlighted and most easily identifiable within the unity of tombstones. Religion is one of the strongest elements connected to human identity. Everyone believes in values he is ready to fight for, even at the cost of life (family, faith, homeland). Religion of a buried soldier can be identified by symbols. A typical sign is a cross, whose form determines particular religion. Another distinguishing sign is a form of tombstone (e.g. tombstones of Muslim soldiers) and religious symbols on the tombstones.

• Military Rank

Army has a well-defined hierarchy of soldiers through officers to the highest commanders. Information on military rank occurs rather sporadically in cemeteries of World War I; they are often located on the graves of soldiers killed in World War II. On the contemporary war graves, there is inducted a military rank of a buried soldier. The system is not uniform. Each country has its own system of military ranks and their abbreviations. For older military cemeteries is typical spatial segregation of graves of soldiers and officers. Famous commanders have majestic tombs, which include busts, statues, etc.

Spatial Structure

Military cemeteries were formed for entirely different conditions than civil cemeteries. Commanders of the warring armies "daily solve more serious problems than burying of dead soldiers"; despite this fact, their bodies were not left on the battlefields. When the front moved, special military forces took care of fallen soldiers. They gathered victims of fighting in places of newly established military cemeteries and took care of their evidence. If necessary, they exhumed dishonourably buried soldiers from provisional shallow graves. Although military cemeteries were created under very difficult circumstances and it could seem that there was not paid much attention, it is not true. The construction of military cemeteries was entrusted to experienced architects during world wars. Their plans had own logic. A special squad paid special attention to the aesthetic organization of graves; crosses or fences were made, for example, by prisoners, many of whom were skilled masters of various crafts.

Mass Graves and Graves of Unknown Soldiers

We often get in contact with a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, where a soldier with not known identity is buried. It was not possible to "deal with" identifying of each soldier and his dignified funeral in vast military operations, large armies and casualties (fatal injuries of soldiers). Because of these facts and the nature of wars, we find the phenomenon of a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier quite often. Military cemeteries of the Carpathians, where the majority of graves of unknown soldiers and small number of identified soldiers were arranged so that the remains of unknown soldiers were stored in a mass grave and the remains of known and identified soldiers were stored in individual neighbouring graves to form a symmetrical whole. Graves are covered with greenery and provided with a plate bearing the inscription: name and surname, date of birth and death, former number of tomb - if graves had been numbered. This reduces the area of original cemetery and its maintenance is not so costly. The remains of graves scattered around are stored in such cemetery according to whether they are identified or not (Bystricky, 2007).

Military Memorials and Military Technique

Apart from graves and tombs, a cross and memorial is often located in central parts of civil cemeteries, which are related to some important event. For military cemeteries is typical dominant military memorial, appearance of which expresses some symbolism, respectively several memorials, that remind some important war events or are specially dedicated to soldiers killed in a particular military operation.

A specific feature of military cemeteries is the fact, that they incorporate some exhibitions of military fighting vehicles, military museums, large sculptures and group of statues depicting the course of the battle, preserved areas of great historical battles, real, reconstructed or artificial military forms of relief - National Military Park in Gettysburg, Normandy, Verdun, Dukla battlefield, etc.

The Vegetation and Landscape Character of Cemeteries

Due to military cemeteries location in space and their overall impression they act in the surrounding countryside, we can point out that they are ahead of civil cemeteries and are models for them. Military cemeteries represent timeless dimension in this spirit of simplicity, sophisticated composition and harmony with the surrounding nature. This obviously is true in maintained cemeteries. Well-arranged lawns, choice of vegetation and its arrangement in space perfectly harmonize this pious place with the surrounding nature. This trend is also gradually applied in civil cemeteries.

Most significant breakthrough in European cemetery culture was the opening of Pére Lachaise Cemetery in Paris in 1807. The cemetery was designed as a picturesque undulated parkland, soon became very popular and it was a model for landscape cemeteries all over the world. In 1840, a famous gardener Jon C. Loudon founded Abney Park Cemetery Arboretum with more than 2,500 tree species in London, which also became a tourist attraction. The first park cemetery was established in Hamburg - Ohlsdorf in 1877 and it has been the largest park cemetery in Europe up to these days. On the other hand, favourable conditions for the development of forest cemeteries were in the Nordic countries.

Vegetation of war cemeteries is a specific identification element and it is particularly true in desolated war cemeteries. In the area of the Carpathians, there was a rule of planting spruce trees and hawthorn along the perimeter of military cemeteries. These trees help us identify forgotten sites even today after more than ninety years (Bystricky, 2007).

Segregation

Despite the integrity and uniformity, we also identify a phenomenon of segregation in military cemeteries. This segregation can occur in several forms. Military cemeteries often represent a segregated part of civil urban and rural cemeteries. Segregated area may also be a part of a cemetery with buried unknown soldiers. A typical feature of segregation in military cemeteries is a spatial separation of graves of soldiers, officers and commanders. As a form of segregation, we can consider a spatial separation of fallen soldiers of different warring armies. Here we can notice a shift in the perception of this fact during World War I and World War II. In World War I cemeteries, soldiers of opposing armies are buried next to each other. This act of humanity has not been repeated in the following periods. Members of participating armies are buried separately in their own cemeteries of World War II, although on the territory of different states. Segregation can be also perceived in terms of visual embodiment of graves (as an example might be different types of graves of the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War in the United States - there was no reconciliation even after the war and the idea of different graves was present).

Study Area

The region of north-east Slovakia was intensely marked by the struggles during World War I and World War II. Military operations in the investigated territory took place from November 1914 to May 1915. The Front line passed through the districts of Bardejov, Svidník, Stropkov, Medzilaborce, Humenné, and Snina. In autumn 1914, the Carpathian Front zone was only a side battlefield, but at the beginning of 1915, its strategic importance increased dramatically. In this area, the Soviet command carried out two general offensives (January/February and March/April 1915) aimed at penetrating through the Carpathian Mountains into the inland areas of Austria-Hungary. For that reason, the territory of today’s Prešov Region became the scene of bloody battles. As a result of these battles, 45,000 soldiers of the Austro-Hungarian, Soviet and German armies were killed, and about 250,000 soldiers were wounded or captured.

North-east Slovakia was a key point in the liberation of Slovakia from the German troops during World War II. The Dukla Pass (402 m a. s. l.), which is the lowest and most passable mountain pass in the border ridge of the Laborec Highlands, became a strategic zone. The mountain pass provides an important road connection between Svidník and the Polish Dukla Pass. We consider the Battle of the Dukla Pass to be the largest and most important fighting event, in which Czech and Slovak military units participated. The main impulse was the declaration of the Slovak National Uprising on August 29, 1944.

The Soviet Union immediately decided to support the rebels by a direct military operation. Finally, the penetration into the Slovak territory was done in the shortest and most difficult way (in the direction of Krosno – Dukla – Prešov) through the Dukla Pass. The Battle of the Dukla Pass began in the morning of September 8, 1944 and ended on October 28, 1944, when the 38th Army troops crossed the defence line: G?ojsce – Ciechania – Svidni?ka – Kapišová – Dobroslava – Korejovce – Krajná Bystrá – north and north-west of Ni?ný Komárnik. The battles fought in the war resulted in many casualties. The 38th Army resulted in 13,579 dead and missing soldiers and 48,750 injured soldiers. The losses of the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps amounted to 1,630 dead and missing soldiers and 4,060 injured soldiers. German losses, including the wounded and missing, are estimated at 50 – 70 thousand soldiers.

The Dukla battlefield area extends from the crossroad of the village Kapišová to the Slovak-Polish border crossing Dukla. The military natural museum, which was open to the public in 1959, is its famous part. There is also an exposition in the nature with military technology in the cadastral areas of Ni?ný Komárnik and Vyšný Komárnik. Reconstructed artillery systems and bunkers of the troops of the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps are also available to the public.

The research area is formed by the Carpathian Mountains, and so the mountainous landscape is dominant. Geomorphological division of the investigated region is based on the geomorphological division provided by Mazúr-Lukniš (1980). The sub-province of the Outer Eastern Carpathian Mountains, constituting the area of Low Beskids and Polonynian Beskids, extends a substantial part of the north-east region of Slovakia. Its highest peak is Busov (1,002 m a. s. l.). The total surface area is almost 3,700 km2. The Low Beskids form a transverse morphological structural gap between the Eastern Slovak Lowland and the Sandomierz Basin. This area includes only two basic tectonic units of the Carpathian Mountains – the Outer Flysch Belt in the north and the Klippen Belt in the south. The Polonynian Beskids stretch primarily across the Ukraine and Poland, and enter the Slovak area only marginally, occupying the north-eastern panhandle. The Bukovec Mountains form a landscape unit of the Polonynian Beskids and a great area of the Bukovec Mountains is a part of the National Nature Reserve of the Polonynian Beskids. The area of the Bukovec Mountains is formed by outer flysch (the Dukla unit), and so it acquires a massive sandstone nature. The investigated area is partially affected by the Inner Eastern Carpathian Mountains. It stretches from the towns of Humenné and Snina to the south. From a geological perspective, this area is identified as a volcanic mountain range.

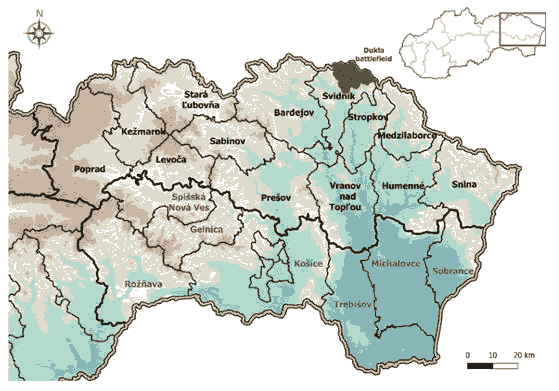

From an administrative point of view, we have focused more intensively on selected districts of the Prešov Region, namely Bardejov, Svidník, Stropkov, Medzilaborce, Humenné, and Snina, through which the Eastern Front passed during World War I. As part of the analysis of World War II, we have included districts of Prešov and Humenné, and from the Košice Region, the districts of Košice town, Trebišov and Michalovce, into the study area (Figure 1).

Analysis of the Military Cemeteries – Location and Characteristics

It seems as if World War I was still in the shadow of World War II, despite the fact that the Slovak military losses in the conflict between 1914 and 1918 were several times greater than losses between the years 1939 and 1945. Regarding the investigated area, we observe some differences that accompanied the emergence of cemeteries during the two world wars.

The emergence of cemeteries during World War I

In the years 1914 and 1915, the area of north-eastern Slovakia became a part of the Eastern Front. Immediate front-line operations affected six districts of the present-day Prešov Region (Bardejov, Humenné, Medzilaborce, Snina, Stropkov, and Svidník) and lasted from November 1914 to May 1915. In this period, north-eastern Slovakia gained the great strategic importance. The Carpathian Mountains zone of the Eastern Front became a place of intense combat operations which influenced the course of World War I. The front lines were formed along the Carpathian mountain range, and the so-called Front cemeteries were established in this area.

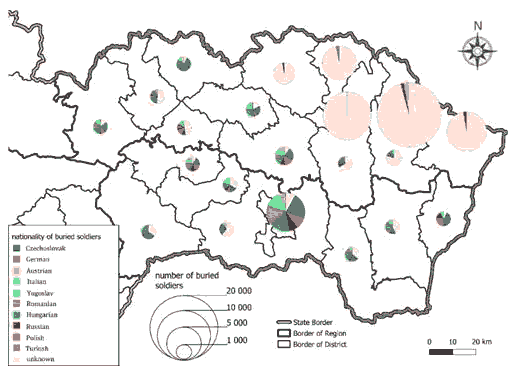

These cemeteries were built far from the human settlements in the mountainous and forested landscape, and since their establishment, they have suffered from a lack of care. In the forest, the grave fields are poorly visible. Graves are rarely marked with a cross or other symbols. A central cross or memorial is present only in some locations. The second group is formed by military cemeteries, which are located in villages and are often part of municipal cemeteries. During a burial ceremony, remains were buried in the common graves of 10 – 20 meters long, evenly arranged. In the centre of the area, between the graves, stone pedestals with a cross and a sign of the years 1914 – 1918 are built. Some graves have circular iron tables, usually corroded, without inscriptions and signs. In most cases, maintenance of the graves as well as of the whole area is very poor, only to provide basic identification for visitors. Such cemeteries could have been built for several reasons. Some municipalities were close to the strategic routes used by military troops while being transported to the front line. We could also include into this group cemeteries along the important railway line from Humenné to Medzilaborce, which further continued through the Lupkov Pass to Galicia. It served as a supply route for the Austro-Hungarian armies in Galicia. It is logical that this route was also used by military hospital transports of the injured soldiers. Many soldiers succumbed to their injuries on the way out of the front line and were unloaded at the nearest station possible. as shows in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Nationality Structure of the Buried Soldiers

Source: processed according to the database of war graves and cemeteries in Slovakia

A specific feature of World War I cemeteries is seen in their multinationality, what is also underlined by the inscription found at the entrance gate of many of them: “The fate of fallen soldiers exhorts us to reconciliation”. The quotation takes a profound significance in connection with the cemeteries of the First World War in the Carpathian Mountains rather than anywhere else. Slovaks, Czechs, Germans, Hungarians, Russians, Austrians, Belarusians, Romanians, Serbs, Poles, Croats, Ukrainians, Slovenes and members of other nations lie in the common graves next to each other. The former enemies, who were trying to kill each other, are resting in the Carpathian Mountains today. Their places of eternal rest have remained a constant memento of the bloody conflicts which arose many years ago. As the map indicates (Figure 2), the highest number of the soldiers who were killed, is in the north-eastern districts, where the front line extended and the bloodiest battles took place.

The high proportion of the unknown soldiers also points at the difficult conditions in their identification and burial. The situation with the remains of soldiers had to be solved by the Austro-Hungarian army. Special army units were established, which, with the help of prisoners of war, dealt comprehensively with the issue of dignified burial of the remains of the Austro-Hungarian, German and Russian soldiers. These units were called Kriegsgr?ber-commands. The task of the units was to clean up the area where the battles took place. First of all, they collected the military material that remained on the battlefield and then they dealt with the remains of the soldiers. These field military units helped to establish a centrally organized record of the deceased. Thousands of bodies had to be exhumed, identified, and buried with dignity. It is interesting that all dead soldiers were treated equally regardless of their nationality, or religion. After the remains of soldiers had been identified, they were transported to the newly built cemeteries. They were buried in special grave fields according to their military status. The only discriminating element that can be perceived is the location of the graves. The Austro-Hungarian and German soldiers were buried closer to the central monument, in other words in a place of honour. Skilled craftsmen, especially carpenters, masons, and stone-masons formed the funeral commands. Craftsmen worked under the leadership of talented architects in uniforms (Dušan Jurkovi?, Heinrich Scholz, Jan Sczepkowski and others).

The architects created unique projects of cemeteries and war memorials, many of which were of immense artistic and cultural values. Under the leadership of experienced experts, the issue of military burials was solved in a systematic and responsible way in Galicia.

In the spirit of the time, military cemeteries were placed in dominant places and were supposed to be sacred and heroic. The questions dealing with the form of central monuments, types of fences, entrance gates, grave fields’ maintenance, etc. were solved as well. In each selected area, a particular cemetery was chosen to serve as a model. The main requirement was that the cemetery would have been suitably incorporated into the surrounding environment. A huge amount of building material was used to build cemeteries.

It is important to note that nothing was really easy during the wars. By the end of 1918, a massive complex of about 400 military cemeteries with approximately 70,000 soldiers buried in 22,590 graves, was built in western Galicia. A different situation was in the Slovak part of the Carpathian Mountains, which administratively belonged to the Kingdom of Hungary. There were also funeral commands, but they were not as precise and systematic as in Galicia. Specifically, these Kriegsgr?ber-commands were no. 1, 3 and 5. Remains of soldiers, who had died on the battlefield, were also collected by the civilian population. Most of the military cemeteries were established in a provisional manner. Individual, common or mass graves had simple wooden crosses, mostly made of birch wood. Cemeteries were enclosed by barbed wire fences or wooden fences. Hawthorn hedges were usually planted around the cemetery and planting spruce trees was very frequent within the cemetery area what can be regarded as an identifying attribute in detection of neglected cemeteries today. In some locations, the systematic work of the funeral command can be documented. Many of the investigated areas had interesting architectural designs. In Medzilaborce district, there are several cemeteries, where graves are arranged according to the prepared plans.

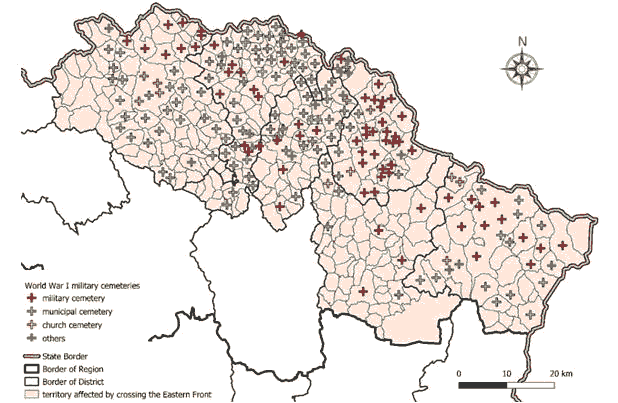

When analysing the spatial arrangement of military cemeteries, certain links can be noticed (Figure 3). In the districts of Svidník, Stropkov, and Bardejov, war graves are mostly part of municipal cemeteries, and to a lesser extent of church cemeteries. War graves are located on the outskirts of the municipal cemeteries, their maintenance rate is very different and is dependent on the interests and attitudes of the local population. Individual or separate military cemeteries are mainly in the Medzilaborce district, to a lesser extent in the Snina district. The main reason is that hard battles were fought especially during the so-called Kornilov’s breakthrough in November 1914 and during the Easter Battle of the Carpathian Mountains in April 1915. Into the category called “others”, we included war graves situated outside the cemeteries and graves on the private land.

Figure 3: Spatial Distribution Of Military Cemeteries In Selected Districts

Source: processed according to the database of war graves and cemeteries in Slovakia

The Emergence of Cemeteries of the World War II Era

Battles in the Carpathian Mountains were similar in both World Wars. The same cannot be said about military cemeteries in that area. The establishment of military cemeteries, their character, location in space and design are completely different when comparing cemeteries of the First World War with the ones of the Second World War. Military cemeteries dedicated to fallen soldiers in World War II started to be built in 1946 and gradually increased their number in the following years. Graves from the Second World War fights in Slovakia are located in several places, so they do not have the character of Front cemeteries. During the war, most of the soldiers were buried in temporary graves, namely in gardens, yards, municipal lands, and many of them remained in the minefields. After the war, they were exhumed and properly buried in the nearest local cemeteries. Unlike the cemeteries of World War I, a lot of smaller cemeteries, which were also spatially connected with the fighting sites, were not built anymore. Large cemeteries were gradually established; where the national principle is being applied. These cemeteries miss the elements of reconciliation, in terms of a common rest of the winners and losers. Their establishment is not uniform, it depends on agreements with certain countries.

In February 1946, the Government of the Czechoslovak Republic adopted a resolution and ordered the Ministry of National Defence to find out the names of all members of the Soviet Army buried in the graves on the territory of the Czechoslovak Republic. On this basis, all district national committees were required to carry out the exhumation of deceased Soviet army members buried in the territory of the country. The remains of Soviet army soldiers were subsequently transferred to the central military cemeteries of the Soviet Army.

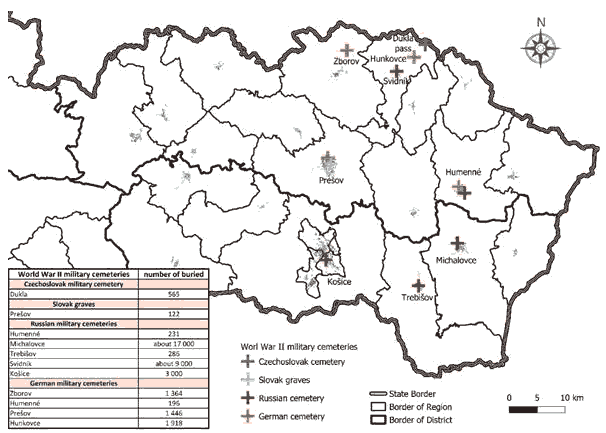

Exhumations of the German soldiers began in Slovakia 46 years after the end of World War II. Since 1991, around 15 thousand fallen German soldiers have been exhumed and buried in six military cemeteries. Most of them have been buried in the cemetery in Va?ec (about 7 thousand). Other German soldiers have been buried in cemeteries in Zborov, Prešov, Humenné, Hunkovce, and Bratislava. All exhumation works were completed in 2000 and were carried out by The German War Grave Commission. The entrustment to carry out these exhumations was given to The National Association for the Care of German War Graves in Slovakia, with its seat in Prešov. as shows in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Spatial Distribution Of World War Ii Military Cemeteries

Source: processed by the data of Ministry of Interior of the Slovak republic

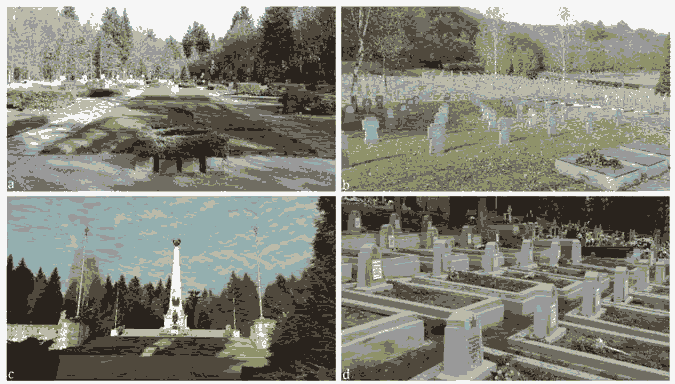

In the investigated territory, there are 11 out of 22 military cemeteries from World War II (Figure 4). Taking into consideration individual or separate military cemeteries, there is a cemetery with a memorial to the 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps in Vyšný Komárnik (Dukla Pass) (Figure 5a). Moreover, there are German military cemeteries in Hunkovce (Figure 5b) and Zborov. As for their location and composition in the country, these cemeteries were unique in that time. Natural materials, stones and wood, possessing local character, were used for their construction. Vegetation and landscape modifications correspond to the character of the local landscape and regional architectural features are also part of suitable completion. Cemeteries of the Soviet army in Svidník and Michalovce belong to the group of individual or separate

cemeteries as well. The Soviet Army Memorial and cemetery in Svidník (Figure 5c) are located directly in the city, their composition, and also the atmosphere, is completely different. Space is dominated by monumental statues and memorials as well as symbols with an ideological tone, which underline the size of the Soviet army and nation. Vegetation elements have been pushed into the background. Other military cemeteries or military graves in Prešov, Košice, Humenné (Figure 5d) and Trebišov are an integral part of town cemeteries. They are not separated by any physical barriers such as fences or vegetation. Their identification is facilitated by the uniformity of gravestones (typical of military graves) and the presence of a central memorial.

Figure 5: A. Cemetery Of The 1st Czechoslovak Army Corps (Vyšný Komárnik, Dukla Pass) B. German Cemetery (Hunkovce) C. Soviet Cemetery (Svidník) D. Soviet Cemetery (Humenné).

Source: terrain research, 2017-2018

Discussion and Conclusion

Mankind has seen many wars and military conflicts during its history that have influenced the course of history and permanently left significant traces. The most destructive and most tragic have always been wars and armed conflicts, in which fighters suffered together with civilians. Besides the loss of human life, huge material losses, transformation of the country in the form of military landforms (defences and front lines, trenches, craters formed by bombs, minefields, etc.) were also parts of the conflict. Geopolitical changes (changes in borders or repatriation of the population) were also results of the conflicts. The 20th century belongs to the most tragic period of history. One of the most devastating and most tragic wars, according to the size, a number of victims and material damage, was World War II. Its horrors, in the form of war cemeteries, preserved sites of major battles, military museums, etc. are palpable even today. However, mankind has not drawn lessons yet and the 21st century does not fall behind the 20th century, as for the number of armed conflicts in the world. We may state that we are in the scattered World War III.

Military cemeteries form an integral part of military history and military area. It is necessary to accept them as part of the cultural landscape and identity. They belong to a particular geographical area in the context of its physical-geographical assumptions and spatial dimension. Military cemeteries have their typical and specific features which help to distinguish them from civil cemeteries. In this paper, we have highlighted changes in the historical context and ways of warfare. All these facts determine the appearance and location of military cemeteries; we have also outlined possibilities of evaluation and typing of military cemeteries. All these presented facts are very important for sustainable heritage management of the militarised landscape (Gheyle et. al, 2014).

The region of north-eastern Slovakia was intensely marked by the fights during World War I and World War II. There are many military cemeteries, which were built in the investigated area during two world wars, however, we have observed great differences in their number, size, location or the way of establishment as well as differences between the professional interest and the general public interest on this issue. Military cemeteries from the period of two world wars represent a certain paradox; they are multinational. Soldiers fighting against each other, have been often buried in the same cemetery, sometimes side by side. Certain symbolism with a message of peace and reconciliation is a typical feature.

Cemeteries are mainly connected to the course of war operations within a territory and, therefore, they were built as frontal cemeteries most of the time. They are scattered throughout the investigated area. In terms of their number, there are quite a lot of them, from individual graves to large central cemeteries. Although burials of soldiers should have been carried out systematically, no central cemeteries, similar to the ones in Galicia, were established. Cemeteries nowadays are in very poor condition; many of them have disappeared or have been forgotten. Based on preserved historical drawings, they are gradually being renewed by volunteers. Due to the high number of cemeteries, it is a very slow process, but on the other hand, it merits appreciation.

Events of World War I shifted World War II and its consequences to the back, almost to oblivion. During the war, soldiers were buried in places where it was at least possible because of the ongoing fighting (in the woods, along the front and transport lines, as part of the municipal cemeteries, etc.). After the war, under the agreements with certain countries, central military cemeteries were established, where the national principle was applied. These cemeteries have a unified character and national elements are part of their composition.

We would like to arouse public interest in the issue of military cemeteries, highlight their memorial, scientific and educational dimensions.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a particular result of the defence research intentions DZRO K-210 NATURENVIR, DZRO K-202 MOBAUT, DZRO K-110 PASVR II, Specific research project 2019 at the department K-210 managed by the University of Defence in Brno and project VEGA 1/0052/17 managed by the University of Presov.

References

Bednárik, R. (1972). Cemeteries in Slovakia (in Slovak). Bratislava: SAV.

Bystricky, J. (2007). World War I – Fights in the Carpathian (in Slovak). Humenné: REDOS.

Chorváthova, ?. (2011). Cemetery. Centre for Traditional Folk Culture.

Cloke, P., & Jones, O. (2004). Turning in the graveyard: trees and the hybrid geographies of dwelling, monitoring and resistance in a Bristol cemetery. Cultural Geographies, 11(3), 313–341.

Cox, G., Giordano, A., & Juge, M. (2010). The geography of language shift: A Quantitative cemetery study in the texas czech community. Southwestern Geographer, 14, 3-22.

?ech, V., & Krokusova, J. (2013) - Anthropogenic geomorphology (Anthropogenic landforms) (in Slovak). Prešov: FHPV PU.

Drob?ák, M., Korba, M., & Turík, R. (2007). Cemeteries of World War I in the Carpathians (in Slovak). Humenné: Redos.

Ebel, J.H. (2012). Overseas military cemeteries as American sacred space: Mine eyes have seen la gloire. Material Religion, 8(2), 183-214.

Francaviglia, R.V. (1971). The cemetery as an evolving cultural landscape. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 61(3), 501 – 509.

Francis, D., Kellaher, L., & Neophytou, G. (2005). The Secret Cemetery. Bloomsbury Collections.

Fuchs, R. (2004). Sites of memory in the holy land: The design of the British war cemeteries in mandate Palestine. Journal of Historical Geography, 30(4), 643–664.

Gammage, B. (2007). The Anzac cemetery. Australian Historical Studies, 38(129), 124-140.

Gheyle, W. (2014). Integrating archaeology and landscape analysis for the cultural heritage management of a World War I militarised landscape: The German field defences in antwerp. Landscape Research, 39(5), 502-522.

Graf, A. (1986). Flora und Vegetation der Friedhöfe in Berlín (West). Verhandlungen des Berliner Bothanischen Vereins, 5, 210.

Hannon, T.J. (1989). Western Pennsylvania cemeteries in transition: A modelfor subregional analysis. Cemeteries and gravemarkers: Voices of American culture, edited by R. E. Meyer, 237-257. Logan: USU Press.

Hockey, J. (2012). Landscapes of the dead? Natural burial and the materialization of absence. Journal of Material Culture, 17(2), 115–132.

Huang, L. (2007). Intentions for the recreational use of public landscaped cemeteries in Taiwan. Landscape Research, 32(2), 207-223.

Hupkova, M. (2008-09). Environment and culture of Czech cemeteries in Czech. Geografické rozhledy, 18(4), 8-9.

Hupkova, M. (2010). Burials and cemeteries-Reflection of Culture of Czech countryside (in Czech). Deník ve?ejné správy.

Johnson, P. (2008). The modern cemetery: A design for life. Social & Cultural Geography, 9(7), 777-790.

Jordan, T.G. (1980). The Roses so red and the lilies so fair: Southern folk cemeteries in Texas. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 83(3), 227-258.

Kirchner, K., & Smolová, I. (2010). Basics of Anthropogenic Geomorphology (in Czech). Olomouc: Universita Palackého v Olomouci.

Kong, L. (1999). Cemeteries and columbaria, memorials and mausoleums: Narrative and interpretation in the study of deathscapes in geography. Australian Geographical Studies, 37(1), 1–10.

Lauermann, L., & Rybansky, M. (2002). Military geography (in Czech). MO A?R, Praha 2002, ISBN 80-238-9274-6.

Light, D. (2016). Cultural heritage of the Great War in Britain. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(6), 495–496.

Lii, Ch. (2015). Heritage and ethnic identity: Preserving Chinese cemeteries in the United States. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21(7), 642–659.

Lincényi, M. (2013). War cemeteries in Slovakia. Evidence, care, management (in Slovak)

Matthey, L., Felli, R., & Mager, Ch. (2013). We do have space in Lausanne. We have a large cemetery’: the non-controversy of a non-existent Muslim burial ground. Social & Cultural Geography, 14(4), 428-445.

Matlovi?, R. (2001). Geography of Religions (in Slovak). Prešov: FHPV PU.

Mikita, M. (2005). World War I – forgotten cemeteries (in Slovak). Svidník: RRA.

Newman, D. (1986-1987). Culture, conflict and cemeteries: Lebensraum for the Dead. Journal of Cultural Geography, 7(1), 99-116.

Pattison, W.D. (1955). The cemeteries of Chicago: A phase of land utilization. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 45(3), 245-257.

Popa, G. (2013). War dead and the restoration of military cemeteries in Eastern Europe. History and Anthropology, 24(1), 78-97.

Pritsolas, J., & Acheson, G. (2017). The evolution of a small midwestern cemetery: Using GIS to explore cultural landscape. Material Culture, 49(1), 49-77.

Quartier, T. (2009) - Personal symbols in Roman Catholic funerals in the Netherlands. Mortality 14 (2), 133–146.

Rech, M. (2015). Geography, military geography, and critical military studies. Critical Military Studies, 1(1), 47 – 60.

Riedesel, G.M. (1980). The geography of saunders county rural cemeteries from 1859

Rugg, J. (1998). A few remarks on modern sepulture’: Current trends and new directions in cemetery research. Mortality, 3(2), 111–128.

Rugg, J. (2000). Defining the place of burial: What makes a cemetery a cemetery? Mortality, 5(3), 259-275.

Slepcov, I. (2003). World War I cemeteries in Eastern Slovakia (in Slovak). Vojenská história, 7(2), 70 – 86.

Slivkova, S. (2011). Design of web guide for cemeteries of World War I in the surrounding of Svidník (in Slovak). Košice: BERG.

Stangl, P. (2003). The Soviet War Memorial in Treptow, Berlin. Geographical review, 93(2), 213–236.

Šumichrast, P. (2010). German war graves in the Slovak Republic, Part 2 (in Slovak). Vojenská história, 14(4), 80–95.

Tanas, S. (2004). The cemetery as a Part of the geography of tourism. Turyzm, 14, 71-87.

Tanas, S. (2006). The meaning of death space in cultural tourism. Turyzm, 16, 145-151.

Tanas, S. (2008). Tourist space of cemeteries. Admission to Thanatotourism (in Polish). ?ód?: Wydawnictwo U?.

Tarlow, P.E. (2005). Dark Tourism: The appealing „dark side of tourism and more. M.Novelli ed. Niche Tourism: Contempora-ry Issues, Trends and Cases. Oxford: Elsevier.

Teather, E.K. (2001). The case of the disorderly graves: Contemporary deathscapes in Guangzhou.Social & Cultural Geography, 2(2), 185-202.

Uslu, A., Bari, E., & Erdogan, E. (2009). Ecological concerns over cemeteries. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 4(13), 1505-1511.

Yarwood, R. (2015). Sustainable deathstyles? The geography of green burials in Britain. Geographical Journal, 181(2), 172–184.

Zapletal, L. (1969). Introduction to Anthropogenic Geomorphology (in Czech). Olomouc: Palacky University.

Zelinsky, W. (1994). Gathering places for America’s dead: how many, where and why? Professional Geographer, 46(1), 29-38.

Received: 03- Dec -2021, Manuscript No. JMIDS-21-9406; Editor assigned: 05- Dec -2021, PreQC No. JMIDS-21-9406 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Dec-2021, QC No. JMIDS-21-9406; Revised: 20-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. JMIDS-21-9406 (R); Published: 10-Jan-2022.